8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

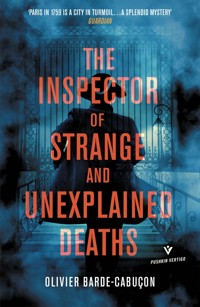

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

'A splendid mystery with an appealingly enigmatic protagonist, plenty of melodrama and intrigue, and a vivid, pungent evocation of a turbulent time' Guardian Everyone has secrets. Especially the king. When a gruesomely mutilated body is found on the squalid streets of Paris in 1759, the Inspector of Strange and Unexplained Deaths is called to the scene. The body count soon begins to rise and the Inspector falls into a web of deceit that stretches from criminals, secret orders, revolutionaries and aristocrats to very top of society. In the murky world of the court of King Louis XV, finding out the truth will prove to be anything but straightforward. Previously published as Casanova and the Faceless Woman Olivier Barde-Cabuçon is a French author and the creator of The Inspector of Strange and Unusual Deaths, who has featured in seven bestselling historical mysteries so far. The Inspector of Strange and Unusual Deaths (previously titled Casanova and the Faceless Woman) won the Prix Sang d'Encre for crime fiction in 2012 and is the first of the series to be translated into English.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

‘Rich with historical detail and macabre atmosphere… a story full of intrigue and secret societies’

Culturefly

‘Fans of Sherlock Holmes-esque mysteries will be enraptured with this historical crime thriller set in pre-Revolutionary France’

France Magazine

‘A heretic monk, a fortune teller, a secret society and petticoats, this is a historical mystery with style’

Le Point

‘A compelling thriller set in pre-revolutionary France with engaging characters that you are never entirely sure if you can trust – a CUB must read!’

CUB Magazine

‘Behind the numerous plot twists you can sense the turning points of history, when alchemy becomes science, when philosophers start to oppose the church, when liberty and free-will are valued for the first time’

Alibi

‘The author makes use of a singular alchemy to blend the scheming and plotting of past days with contemporary concerns’

NVO

‘A series to follow’

Memoire des arts

For Christine, Thibault, and all my family

I go where I please, I listen to the people I meet, I answer to those I like; I gamble, and I lose.

crébillon fils

CONTENTS

I

Nothing in all Creation exerts such power over me as the face of a beautiful woman.

casanova

Night swarmed through the streets of Paris, casting its black veil over the carriage standing motionless in the middle of the deserted thoroughfare. Buttoned tightly in his dark coat, the driver kept a close rein on the horses as they jostled nervously. A slender, cloaked silhouette climbed down from the coach. The hood, pulled low, concealed the features of a young girl. Shadows stole over the surrounding walls, extending hooked fingers in her direction. A horse tossed its mane. The driver stared straight ahead, imperturbable.

‘It’s late. Take care, child: good people cleave to daylight, but the wicked come out at night!’

The voice came from inside the carriage. Tired, but with a rich timbre that was pleasing to the ear. As if in response to some invisible signal, the vehicle shuddered into life with a clatter of wood and iron. The unknown girl trembled. She stood alone, her white fingers clenched as if preparing to strike out with her fist. The darkness made everything unfamiliar. Fantastical forms suggested themselves to her searching eyes. Unwittingly, throughout her childhood, her mother’s bedtime stories had peopled her nights with werewolves, thieves and ghosts. For an instant, she thought she heard footsteps, and froze to listen. But there was nothing. Only silence.

At that moment, the clouds shredded and pale moonlight flooded the street, revealing the entrance to a small courtyard, and the red glow of a bread oven on its far side. The young 10girl started forward, happy and relieved. A tinkling, crystal laugh rose unbidden in her throat, and she strode quickly in the direction of the wavering light.

A sudden movement pierced the night. A shadow loomed and spread over the walls, in the girl’s pursuit. Presently, a scream tore through the dark.

A mild spring night in the year 1759. The light from the oil lamps and candles, flickering in their lanterns, had drawn a crowd of onlookers, like fascinated moths. The precinct chief swallowed hard and averted his gaze from the bloody spectacle before him.

‘Dead,’ he stated. ‘I have no idea why or how it was done, but the skin has been completely torn from her face. No one could recognize her in that state.’

‘As though it had been eaten away by a wolf!’ declared one of his men.

A muffled cry greeted his words, and a low rumour spread through the assembled company.

‘Wolves! The wolves have entered Paris!’

The precinct chief shot a dark look at his officer.

‘I’ll thank you to keep your thoughts to yourself, in future!’

The man shrank back, colliding as he did so with a solemn, impassive figure—a recent arrival, who had been watching in silence.

‘Ah!’ There was a note of irritation in the precinct chief’s greeting. ‘The Inspector of Strange and Unexplained Deaths… Who in hell’s name sent for you, Volnay? And how did you get here so quickly? Do you never sleep?’

Volnay stepped forward. He was a tall young man with a pleasant enough face, offset by his dark gaze and stiff bearing. The moonlight modelled his features in stark relief. He wore no wig and his long, unpowdered, raven-black hair floated 11behind him on the gentle breeze. From the corner of his eye, a scar curled around his temple, prompting its share of speculation. He was plainly dressed in a black jerkin, with a bright, white, frill-necked shirt and cravat. Despite the late hour, he was impeccably turned out. He made no reply to the precinct chief, but knelt and examined the body from head to toe before turning to his colleague.

‘I want the body brought for examination—not to Châtelet. Not the city morgue. You know the place.’

The precinct chief shivered and tried to protest.

‘You’ve only just got here. Let us begin our inquiries before we decide if this is a case for the scientific police!’

Volnay gave him not so much as a glance.

‘By order of the king,’ he said firmly, ‘I am authorized, as you know, to investigate every strange or unexplained death in Paris. As you can see, we are in the presence of a victim who has had the skin torn carefully from her face, so as to render her unrecognizable.’

He took a bell lantern from the grasp of an officer of the Royal Watch and cast the dim light of its tallow candle over the body.

‘As you may also see, there is not a trace of blood on the woman’s clothing. From which it seems clear she was killed first, then had her garments removed, was disfigured after that, then dressed again, and finally placed here. And sure enough, even though your officers have trampled everything and very probably spoilt any available clues, I have observed no spot or trail of blood in the vicinity.’

The precinct chief shook his head and breathed a long sigh.

‘Clues! You’re obsessed, Volnay…’

‘If I can trouble you to establish a police cordon and keep everyone at bay,’ Volnay continued smoothly, ‘I would prefer us to attend the scene of the crime in privacy.’ 12

He waited while the order was issued and carried out, then took the victim’s hands in his and examined them carefully.

‘The hands are well cared for, and show no signs of manual labour,’ he said quietly, as if thinking aloud. ‘This is a person of some standing.’

‘Or a whore from one of the finer parts of town.’

Volnay gave no reaction, but scrutinized the dead woman’s body, pausing briefly at her breast, and stopping at her neck. Delicately, his long, slender fingers lifted a small chain and medallion engraved with an image of the Virgin. On the reverse, he read a Latin inscription, and translated it with ease.

‘Lord, deliver us from Evil.’

Volnay turned to his colleague with a thin smile.

‘A somewhat unusual whore, if so!’

Half stooping, he began a methodical examination of the ground. But so many feet had trodden the area around the body that it was impossible to make anything out. He searched in his pocket, took out a stick of charcoal and a piece of paper, and began to draw the dead woman and her surroundings. The precinct chief grinned in amusement.

‘So, it’s true what they say: you’re quite the artist. You’ve missed your vocation!’

Volnay answered with a cold stare. At times, his blue eyes appeared veined with ice.

‘Every detail is important in its own, particular way. I commit them all to memory, but not only that—I note everything down on paper, too. A murderer may leave traces of his presence at the scene of a crime, just as a snail leaves its trail of slime. Observation is the bedrock of our work. Take an example—have you counted the number of people in their nightclothes at the front of the crowd?’

The precinct chief had not. 13

‘Six,’ said Volnay smoothly, sketching all the while. ‘Unless others have arrived in the last minute. Am I right?’

‘Dear Lord, so you are!’

‘I should like your men to question them. They are here in their nightclothes because they live nearby and were alerted by the noise. They may have seen something, or noticed someone.’

Their exchange was broken by the creak of cartwheels on the cobblestones. At the sight of the new arrival, the precinct chief’s stomach churned, and he swallowed hard. Volnay raised one eyebrow.

‘Ah, here he is! I had him sent for. Only the Devil himself is quicker, as you can see!’

The cart was driven by a dark, spectral figure shrouded in a monk’s habit, the cowl pulled down to conceal his face. Many of the onlookers crossed themselves. Noiselessly, fearfully, the crowd shrank back as the vehicle passed.

‘Ah yes—and who discovered the body?’ asked the inspector sharply.

‘That gentleman there.’

Volnay looked in the direction of the tall individual who had been pointed out. His jaw dropped in recognition. Serene and self-assured, the fellow stepped forward. He had a pleasing, sallow face. He was elegantly dressed in a velvet coat of deep yellow with a woven pattern of small flowers and cartouches, and buttons covered with silver thread. His jabot and frilled cuffs were of costly bobbin lace. His entire person radiated natural good humour and an irresistible, lively charm.

‘The Chevalier de Seingalt, sir!’ His tone was bright and amiable.

‘I know who you are, Monsieur Casanova,’ said Volnay, quietly. 14

Who had not heard of Giacomo Casanova the Venetian, by turns banker, swindler, diplomat, army officer, swordsman, spy, magician, and of course, ever and always the arch-seducer? Casanova was a walking legend, whose reputation preceded him wherever he went.

Volnay’s expression left no doubt as to his profound disapproval of the immoral behaviour of such as Casanova, a man who bedded barely pubescent girls, and sometimes even mother and daughter together.

‘The Chevalier de Seingalt, at your service!’ persisted the other, ever-eager to be addressed by his title. ‘Decorated with the Order of the Spur by His Holiness the Pope himself!’

‘Indeed. Who among us is not?’ retorted Volnay, with a scowl.

He knew perfectly well that the title—pronounced Saint-Galle in the French manner—was a fabrication. The chevalier himself responded with insolent charm to anyone who laughed at his affectation, urging them to make up their own title if they were jealous! Volnay observed him quietly. He had no liking for Casanova and his kind, but the man was a creature of the great of this world, or tried his best to seem so, at least. He had arrived in Paris three years earlier, and his energy, vivacity and intellect had secured him an entrée to the highest circles. He frequented the loftier ranks of the nobility—the Maréchal de Richelieu, or the Duchesse de Chartres—and the country’s intellectual elite. He was a man to be handled with care.

‘How did you discover the victim?’ Volnay asked, curtly.

‘It happened that I was accompanying a delightful young lady back to her place of residence. As you know, nothing in all Creation exerts such power over me as the face of a beautiful woman! Well, we were going on our way when, quite simply, we ran into the body lying here. I bent down to lift her hood and… my companion screamed, very loudly.’ 15

‘Did you notice anyone nearby, when you discovered the dead woman, or just before?’

‘Absolutely no one, Inspector.’

Without a word, Volnay turned on his heels and knelt once more beside the body, forcing himself to scrutinize the bloodied mask of the face, in an effort to understand how the murderer had proceeded. A wolf? Certainly not, but very likely something far worse.

The scene was bathed in silvery moonlight. Volnay cursed suddenly, under his breath. Transfixed by the dead woman’s face, he had omitted to search her body. Now, mechanically, his hands discovered and pulled a letter from the victim’s pocket, almost before he knew what he had done. Volnay felt Casanova’s eyes on him. He glanced at the seal and experienced a wave of dread.

‘Well look at that, Inspector! A letter in the dead woman’s pocket!’

‘You’re quite mistaken, Chevalier,’ said Volnay, allowing Casanova his usurped title for once. ‘This letter just fell out of my sleeve.’

‘But I assure you—’

Volnay shot him a cold stare.

‘It’s mine, I tell you!’

Casanova fell silent, but he continued to watch the inspector with keen interest.

Among the onlookers, a black-clad figure stood watching Volnay’s every move, long and lean as a hanged man against a winter sky. His face and the skin of his bald scalp shone disconcertingly white, like milk or a faded flower on a tall stalk. His grey eyes seemed washed of all colour. They held not a shred of humanity. He turned at the approach of the cart. The monk sat waiting placidly for the corpse to be lifted aboard. 16The pale man frowned, as if struggling to remember where he might have come across the hooded figure—the source of such fear and astonishment—before. A hideous grin lit the pale man’s face, but stopped short of his eyes. His mouth spat a silent curse. Hastily, furtively, he made the sign of the cross. He noted Casanova’s presence with interest, and gave a short gasp of surprise when Volnay slipped the letter discreetly into his pocket. His features hardened. After a moment’s hesitation, he pushed through the crowd and hurried away, as if the Devil himself were at his heels.

It was late when Volnay made his way home. The night was beset with shadows. He gripped the hilt of his sword as he walked, alert to the silhouettes of furtive figures who crossed his path, and others who kept out of sight, behind pillars or under the dark overhangs of the houses. Each morning, the street sweepers of Paris gathered up the bodies of incautious nightwalkers.

A cobbled passage led from Rue de la Porte-de-l’Arbalète to Rue Saint-Jacques. Stone wheel guards jutted from the walls, protecting them against passing carriages. Partway along, the passage opened onto a series of tiny courtyards, the first of brick and stone, with a stone well in the middle; a second, smaller court, and a third, even tinier, the last almost entirely filled with a tall acacia tree. Here Volnay lived, happy with his own company, and that of his tree, glimpsed from every window on both floors of his little house. The acacia was a symbol of life in this unfrequented place, a link between the earth with all its woes, and the indifferent eye of heaven.

Volnay stepped inside and bolted the heavy door behind him. The ground floor served as his parlour, study and dining room. But the house’s raison d’être, its defining, unifying force, was its books. The books filled Volnay’s living room, glowing 17in the candlelight. Their remarkable sheen lit the walls, nooks and corners with scattered specks of ochre and gold. There were books bound in leather or parchment, and books with studded or embossed covers. Their presence and prominence hinted at the scope of their owner’s inner life, and its limits. Two mismatched armchairs and a wooden table set with fine candlesticks stood their ground with a determined air. Faded tapestries—family heirlooms, perhaps—contributed an unexpectedly soft touch.

‘And how are you, my fine friend?’

The question was addressed to a splendid magpie, eyeing Volnay through the bars of her cage. She had a long tail, and black plumage with a purplish sheen on her back, head and chest. Her underbelly and the undersides of her wings were pure white, and her tail showed flashes of oily green.

‘What, no answer? Are you sulking?’

The bird kept her silence. Volnay shrugged lightly and crossed the room to one set of bookshelves. He chose a volume bound in red vellum, caressed its cover lovingly and settled himself into his favourite armchair beside the chimney, piled with extinct logs. After a moment’s hesitation, he placed the book on a side table and fished in his pocket for the young victim’s letter. He had taken it—unusually for him, and right under the nose of the Chevalier de Seingalt—for one very simple reason. He stared gloomily at the seal, and sighed heavily. The wax was imprinted with the seal of His Majesty the king.

Why me?

Dark thoughts flooded Volnay’s mind. The monarch’s depravity knew no bounds. It was rumoured that he purchased or stole young girls from their families and took them to live in the palace attics, as fodder for his debauched appetites. In Versailles, Volnay knew of two quarters—the Parc-aux-Cerfs and Saint-Louis—where one or more secret houses were 18used as trysting places for the king and his young conquests. When royal bastards were born of these illicit liaisons, they were removed from their unfortunate mothers forthwith and placed in the care of wet nurses.

What if the young woman had come from the king’s bed?

Louis XV’s favourite, Madame de Pompadour, had installed the young girls in the Parc-aux-Cerfs, the better to satisfy the king’s unstinting desires. No longer the object of royal lust herself, and fearing to lose her position at Court, she had devised a way to pander to His Majesty’s pleasure with a hand-picked array of willing girls from the lower orders, all thoroughly unversed in the intrigues of Court life. In this way, La Pompadour nipped potential rivals in the bud, by ensuring none of the king’s mistresses rose too high in the royal favour. Ultimately, she dispensed with the girls by marrying them off to members of the royal household.

Volnay often wondered how Louis XV reconciled his vices and his very great fear of God. But the king considered himself a ruler by divine right. Hell was for other people. And he was at pains to ensure that the unfortunate children recited their prayers after he had taken his pleasure, so it was said, to avoid eternal damnation!

Deep in thought, Volnay turned the letter over and over in his fingers, but he did not break the seal. The king’s secret harem of young mistresses was common knowledge, but Paris was rife with even wilder rumours: the king was said to have contracted leprosy as a result of his debauchery. Bathing in the blood of innocent children was the only thing that kept him alive.

What if the young woman had come from the king’s bed? Volnay asked himself, again. What should I do then?

His logical, deductive mind had run ahead, to the inevitable conclusion: doubtless, one day, he would be forced to 19return the letter to its rightful owner. He was even more careful not to break the seal now, despite his burning curiosity. He swore under his breath.

‘To think that that arch-rogue Casanova saw the whole thing!’ he declared out loud in exasperation. ‘Casanova!’

‘Casa! Casa!’

Volnay jumped half out his skin, then turned to look at the great birdcage and its splendid occupant.

He smiled.

‘Yes, that cretin Casanova!’

‘Cretin Casa! Cretin Casa!’ repeated the magpie obediently.

Volnay laughed aloud.

Casanova had played a superb hand, drinking little but frequently refilling his opponent’s glass, losing at first to raise the stakes, then delivering his fatal blow with immediate, sobering effect.

‘I played on my word, Chevalier…’

The Venetian straightened himself in his armchair, a slight smile playing at his lips.

‘A gambling man keeps his money about his person, Joinville,’ he said quietly.

His opponent rolled his shoulders uncomfortably and ordered more drink. He peered anxiously into Casanova’s face, from which all trace of affability had now disappeared. The pair sat in a smoke-filled den where a player’s rank in society counted for less than the cash he could lay on the table. A place for cavagnole and manille, faro, biribi and piquet. Ladies pressed their generous bosoms against the shoulders of the luckier players. The Chevalier de Seingalt’s eye alighted on a girl in pink silk stockings, then turned coldly back to his debtor. He never mixed money with pleasure, unless the money belonged to someone else. 20

‘You had a run of luck tonight, Giacomo,’ said Joinville, gruffly.

The Venetian gave a quick smile and sat back in his armchair, eyes half-closed as if remembering things past.

‘There have been times in my life,’ he confided lazily, ‘when I gambled daily and, losing against my word, found that the prospect of having to pay up the next day caused me greater and greater anguish. I would fall sick at the very thought, and then I would get over it. As soon as I regained my health and powers, I would forget all my past ills and return to my usual pursuits.’

‘So you played on your word, too!’

Casanova opened his eyes wide.

‘Could that be because my word was valued more highly than yours?’ he retorted, wickedly.

A peculiar, bitter smell wafted from the candles on the table, stinging the nostrils. With forced gaiety, Joinville snatched his tankard from the serving girl’s hands and tried, clumsily, to pinch her backside. She trotted off, giggling. Joinville shrugged, and boomed out a song that had been a great source of merriment the length and breadth of France under the previous reign, when the Italian-born Mazarin was first minister, governing the country with Anne of Austria, his supposed mistress, the erstwhile infanta, and mother of the child king Louis XIV:

‘Mazarin’s balls don’t bounce in vain,

They bump and bump and rattle the Crown.

That wily old Sicilian hound

Gets up your arse, princess of Spain!’

Casanova wasn’t singing. He sipped his Cyprus wine and kept his opponent firmly in his sights. 21

‘I’ll take your credit,’ he said suddenly, ‘if you can tell me a good story. I know you’re privy to all the secrets at Court.’

‘Well now! Where to start?’

‘With whatever is of greatest interest.’

Joinville took a deep breath. He was a wine merchant, serving the finest households in Paris. His honourable dedication to sampling all of his merchandise had given him a fine paunch; and his dutiful drinking bouts with each eminent client made him an inexhaustible fount of gossip, ingested more or less accurately, depending on his state of drunkenness at the time.

‘Do you know how La Pompadour first seduced the king? She attended a costume ball dressed as Diana the Huntress, with threads of silver plaited in her hair, and her breasts very much on display, carrying a quiver of arrows and a bow on her back. The king had her there and then.’

Joinville heaved himself to his feet and declaimed:

‘What care I, who seem so bold?

What if my husband be cuckold?

What care I for anything,

When I’m the mistress of the king?!’

Casanova stifled a yawn. Joinville watched in alarm as he got to his feet.

‘Wait! Wait! There’s fresher meat than that! The Devout Party—the religionists—detest La Pompadour, as you well know. They’ll do anything to destroy her…’

‘Nothing new there,’ remarked Casanova, adjusting his waistcoat and looking around for the girl in the pink silk stockings.

‘Wait, I tell you! They say the Devout Party have found a way, and soon La Pompadour will be a mere memory.’ 22

‘A plot?’ Casanova was interested now.

‘So it seems. But I know nothing more for the moment. Father Ofag, a Jesuit, is the leader.’

‘Is that all?’

‘His devoted accomplice goes by the name of Wallace. A soldier. Visionary type. Skin as white as milk, and eyes to make your hair stand up straight on your head. He’s very dangerous.’

Joinville underscored his message by dragging his thumb across the skin of his throat. Casanova looked at him thoughtfully for a moment, cold and calculating.

‘I’m not sure I believe you,’ he said at length. ‘But get me some first-hand information and I’ll cancel our debt. I may even throw in a few coins, but only if it’s truly worth my while.’

He glanced at a woman in a low-cut corset standing at a table nearby, then reluctantly turned his attention back to Joinville.

‘Do you know a police officer by the name of Volnay?’

Joinville laughed heartily.

‘Of course! Volnay saved the king’s life a couple of years back, when Damiens tried to assassinate him. The king knighted him, made him a chevalier.’

‘Indeed!’

‘He is known as an upright man of great integrity. The king asked if he might grant Volnay a favour for having saved his life, and Volnay answered that he should like to be put in charge of investigating every strange and unexplained death in Paris. The king laughed at the idea, but he was in Volnay’s debt. And so, for the past two years, Volnay has been just that: His Majesty’s Inspector of Strange and Unexplained Deaths, with no particular mandate other than to investigate especially nasty or complicated cases of murder in the capital. It was he who solved the Pécoil affair. You’ve heard about that?’ 23

The Venetian shook his head. Joinville lit a cigar and leant forward with a slight, condescending smile.

‘Pécoil had accumulated vast riches from the gabelle, the salt tax. He kept it all under his house, in a vault sealed by three doors of solid iron. Like any self-respecting skinflint, he would go down each evening and revel in the sight of his gold. One evening, he failed to come back up. His wife and son were concerned, of course, but it was two days before they sent for the police and forced the three doors. They found Pécoil with his throat cut, lying on the floor beside his treasure, from which not a single crown was missing. His arms were outstretched, reaching into his blackened, burnt-out lantern, the flesh partly consumed by fire.’

Joinville blew a thick cloud of smoke.

‘Volnay solved the case in less than a week. They say he’s highly competent.’

Casanova raised one eyebrow.

‘I hope he is,’ he said coldly. ‘For his own sake.’

II

What is beauty? We cannot say, and yet we know it in our hearts.

casanova

In the darkness, the wood cracked and the furniture creaked. Were they truly inanimate, and devoid of a soul? The sounds, and the memory of the faceless woman, woke Volnay with a start in the depths of the night, just as a pair of blood-drenched lips placed themselves upon his own. He fell back into a deep sleep, but the woman with her bloodied mask returned again, holding out a letter which he stubbornly refused to take. He tore himself from his nightmare when she threw off her clothes and sat astride him, like a she-devil come to ride him as he slept.

Whoever sleeps on his back is sometimes suffocated by spirits of the air, who torment him with attacks and tyrannies of every sort, and deplete the quality of his blood with such sudden effect that the man lies in a state of exhaustion and cannot recover himself.

His learned collaborator, the monk, would doubtless have explained it thus. But he would be busily occupied now, with a meticulous examination of the body of the faceless woman.

Volnay thought of the letter he had removed from the body. He fought the temptation to read it. He rose from his bed and lit a candle. The silence of the night fed his thoughts, and he tried to get his ideas in order. He examined the sketches he had made at the scene of the crime, elaborating theory after theory, but still he could not sleep. And so, early that morning, it was with a haggard face that he answered the beating of a fist on his front door. 25

Opening it, Volnay had expected anything but the apparition that met his eyes: a young woman, her waist most admirably clasped in a brocade gown in three different shades of blue, trimmed with silver lace. The cut and fabric flattered her well-rounded breasts, pushed up tight in her stays. She was enveloped in a delicious fragrance of roses, by turns sweet, peppery and fruity, with base notes of amber and musk. She looked not yet twenty; her features were pure and clear, yet already an application of crimson gloss and a touch of silver glaze emphasized the dark brilliance of her almond-shaped eyes. Her hair was blacker than the blackest night, held in place by a multitude of pins, so that it seemed speckled with stars. There was a luminous quality to the skin of her throat, and her waist was slender but healthy and firm. Volnay lowered his eyes, and discovered a delicate foot, light as air, that quickened his pulse.

‘Madame…’

‘Mademoiselle Chiara D’Ancilla, Chevalier,’ she said in a charming, cajoling voice.

Volnay blinked briefly. He was rarely addressed by his title, and never used it himself. Who was this beautiful young Italian woman, and what did she want? He employed a woman to keep house, and see to his provisions and laundry, but no other female presence ever brightened his simple dwelling. It was a place dedicated to rest, reading and reflection.

‘May I come in?’

He realized that he had been standing there in the doorway without the least show of manners. Hastily, he stepped aside to let her pass, noting how the tiny pleats in the back of her dress showed off the sheen of its silk and the softness of the satin. Once inside, the young woman stood motionless, gazing at the gold-tooled bindings that lit the room with their refulgent glow. She admired their elegant, abstract patterns, 26their azure motifs, the foliage and palm fronds entwined in their decorative frames.

‘Oh, I see you’re a lover of books!’ she breathed appreciatively. ‘So am I—they hold all human knowledge!’

She turned to him and added, in a charming voice:

‘All human hopes and desires, too.’

She ran her delicate hand along the spines, and Volnay trembled, in spite of himself, as if she had caressed some part of his body. She took out a book bound in a pretty pattern of five fleurons around a central lozenge, framed by four triangular corner pieces.

‘Treatise on the Condition of the Human Body after Hanging,’ she read in horror-struck tones. ‘Dear God, why ever do you read such things?’

Gently, Volnay removed the book from her grasp.

‘It is thanks to this book that I understood how to determine whether a person has been strangled or hanged. The marks upon the neck are different in each case, and the angle of the break at the nape is also…’

He broke off, seeing her shudder.

‘Forgive me such unpleasant details. It was merely by way of explaining to you that my trade obliges me to take an interest in how people meet their deaths. It is possible to discover a great deal by examining the scene of a crime, and the victim’s body. The corpse alone holds a wealth of clues, as do the clothes, and everything must be examined with the utmost care. My collaborator, a monk and a learned man of science, devotes himself to the task. The deciphering of footprints, or how blows have been delivered and received, is truly an art.’

He paused, and sighed.

‘Yet it interests no more than two people in the entire kingdom!’ 27

The young woman stared thoughtfully at Volnay, who was scarcely much older than she was herself. Her gaze lingered on the fine scar running from one eye to his temple. And on the half-moons of shadow beneath his lower lids. So this was what an Inspector of Strange and Unexplained Deaths looked like? Suddenly, Chiara D’Ancilla froze, and shivered, as if a new thought had just struck her.

‘Have you ever burnt books, Inspector?’

Her passionate feelings on the subject were quick to find expression in her beautiful, dark eyes.

‘Indeed not, Mademoiselle, never!’ said Volnay, hurriedly, because it was the truth and because he had no desire to incur this woman’s displeasure.

He might have added that he had even saved books on occasion, stealing back volumes that had been confiscated by the censors, without a second thought. His answer brought a smile back to the young woman’s face. She spoke animatedly.

‘I knew it—one cannot be both a reader and a destroyer of books! Ah, you’ve read all our philosophers: Rousseau, Voltaire, Diderot and Baron d’Holbach! How very bold of the king’s personal policeman. What does Monsieur de Sartine, our city’s chief of police, have to say about that?’

‘He hardly ever comes here,’ said Volnay, unsmilingly.

She took a few steps around the room, and again he admired her graceful but unaffected carriage. Morning light bathed the walls with a honeyed glow. A delicate shaft of sunshine caught her figure, so that she stood in a radiant halo of gold. She had stopped to admire a red morocco binding stamped with a mesh of fine dots. Just at that moment, the bird shifted in its cage. She had not noticed it until now.

‘Oh! A magpie!’

‘Mag-pie! Mag-pie!’ The bird echoed the familiar exclamation. 28

The young woman clapped her hands in delight.

‘What is this miracle of nature?’

Volnay joined her beside the cage, pleased to have found a pretext to step inside her fragrant cloud.

‘There is nothing miraculous in it, Mademoiselle. Magpies are even more accomplished than parrots when it comes to reproducing human speech. Few people know this, but a little teaching is all they require.’

They stood in silence for a moment, contemplating the bird’s magnificent plumage as it perched motionless now, its beak pointed in their direction. Slowly, almost regretfully, the young woman turned to Volnay.

‘Monsieur, the reason for my coming here will doubtless surprise you,’ she said in tones of the utmost seriousness. ‘And so first I must tell you who I am. I am Italian, as my name suggests. My father is a widower: the Marquis D’Ancilla. He has significant interests in your country, and we live here all year, apart from the summer, which we spend in Tuscany. Like you, I read a great deal, but while you devour philosophy, I am drawn to the natural sciences, astronomy, mathematics—’

‘Indeed, you are a scientist at heart.’

She frowned very slightly with one eyebrow, displeased at having been interrupted.

‘A scientist in practice too. I like to test theories through practical experiments, and—’

‘Doubtless you have a laboratory?’ he ventured, knowing full well that every person of means with an enquiring mind had their own private workroom.

This time she took a step closer, eyes flashing.

‘You must find me feeble-minded indeed to keep finishing my sentences for me. Or is it because I’m a woman?’

Volnay excused himself hurriedly. The young aristocrat was placated, and continued: 29

‘I should like to visit the place where the police take all the corpses!’

The stupefaction on Volnay’s face must have been comical indeed, because Chiara burst out laughing. But the Inspector of Strange and Unexplained Deaths took no offence at her gentle mockery.

‘You see, sir, I am interested in the natural sciences. I have devoted much time to the study of the human anatomy, and I am… very inquisitive.’

Volnay sighed. He thought of the hideous place she was asking to visit, where the corpses were salted, then stacked like loaves in an oven.

‘It is no spectacle for a person of your quality.’

‘Inspector…’

She moved closer and placed her hand lightly on his arm.

‘Mademoiselle, believe me, it can be done, but you would regret the sight of it your whole life.’

Volnay thought she seemed vexed, but he was wrong. She continued briskly:

‘Well then. Enough of that.’

Then she seemed to hesitate for a moment.

‘They say you’ll be leading the investigation into the murder of a woman whose face was torn off.’

‘News travels fast in Paris!’

Chiara smiled sweetly, with her hands clasped behind her back, like a good little girl.

‘Paris is such a small city.’

She paused for the briefest of moments, before asking innocently:

‘Have you been able to identify her?’

‘Mademoiselle, all the skin on her face has been removed. Who could recognize her in such a state?’

She turned pale. Volnay was alarmed and led her to a chair. 30

‘We shouldn’t speak of such things! Shall I fetch you a glass of port?’

‘A glass of water, please.’ She took a deep, slow breath. ‘And you say you haven’t been able to identify her? Did she have anything about her person? A name embroidered into an item of clothing? Any papers?’

She noticed Volnay’s cold stare.

‘Some jewellery, perhaps?’ she ventured.

She gave a forced laugh and added:

‘Some women can be recognized by their jewellery alone!’

Volnay was perplexed. He shook his head.

‘A glass of water,’ murmured Chiara. ‘Please…’

‘Straightaway,’ said Volnay.

He was surprised, on his return, to find her standing at his desk, examining his papers.

‘Mademoiselle?’

She turned to him, and her expression was open and candid.

‘I was admiring your lacquered work cabinet. It must have cost a small fortune.’

‘It came to me from my father,’ he answered, coldly. ‘I’m pleased to see you are feeling better.’

Relinquishing any attempt at manners, he held the glass out for her to take, but did not move. She walked slowly to where he stood, her eyes fixed firmly on his, but pouting sulkily like a naughty little girl who has been caught in the act. She took the glass, and their fingers brushed. Volnay felt a tremor of excitement throughout his body.

‘It is very fresh, thank you.’ She returned the glass, after taking the tiniest of sips.

Volnay was troubled indeed. He took the glass, resisting the urge to drink from it in turn, in the delicate trace of her lips. She hesitated for a moment, then walked across to admire 31the magpie once again, and played with it through the bars of the cage. The bird beat its wings and set about smoothing its feathers.

‘Is she any more of a prisoner than we poor humans, labouring under the yoke of our own rules, conventions and prejudices?’ she pondered.

The question took Volnay by surprise. He watched her closely.

‘You must find me very strange,’ she went on in some embarrassment, ‘but you see, my lady-in-waiting left to care for her sick mother, and has sent no word since. When I heard the news of the killing, I wondered if…’

Volnay relaxed. Here at last was the reason for her persistent questioning.

‘The post can be inefficient, Mademoiselle. But I can assure you that—’

There came a knock at the door. Irritated, Volnay excused himself and went to open it. He was a man who seldom entertained, and kept the company of no one but his magpie and his monk, yet he was receiving more visitors than ever before this morning. His surprise was all the greater when he saw the man standing outside his door:

‘Casanova!’

‘Chevalier?’

Chiara D’Ancilla’s delicate presence in the room he had just left prevented him from inviting the Chevalier de Seingalt to come inside. His visitor was clearly offended, but said nothing.

‘I come with greetings.’

‘What can I do for you?’ asked Volnay, standing his ground in the doorway.

‘Well, you might invite me in off the street for a start,’ said the Venetian coldly. 32

Reluctantly, Volnay stood aside.

‘I have a guest; I must ask you to be brief.’

He heard the rustle of Chiara’s gown and was alarmed to see a sparkle in Casanova’s well-trained eye. She had appeared behind him, and Volnay saw straightaway that Casanova was sizing her up as a potential conquest. For her part, the young woman seemed quite struck by the tall, handsome man—who stood a good head above Volnay—with his robust figure, healthy complexion and smiling eyes. Cold fury gripped the inspector, but he retained his composure.

‘Mademoiselle…’

Casanova had sunk into a deep bow.

‘Allow me to introduce myself, since our friend Volnay will not. The Chevalier de Seingalt, at your service.’

And he bowed once more, but without taking his eyes off Chiara this time.

‘Forgive me, I’m quite forgetting myself,’ said Volnay drily. ‘Chevalier de Seingalt, allow me to introduce Chiara D’Ancilla.’

‘Your family is widely known,’ declared Casanova, bending again to kiss the tips of the young woman’s fingers. ‘These are the moments I treasure most in life: chance encounters, unforeseen, unexpected, and all the more delightful for that!’

Volnay rolled his eyes to the ceiling, but Chiara considered the Venetian carefully.

‘Are you not the one they also call Casanova?’

She pronounced the name with a certain anxiety, and a glimmer of excitement, too. The Chevalier de Seingalt was unsurprised. His reputation preceded him, and he attracted the attention of women wherever he went.

‘What did you want to tell me?’ asked Volnay brusquely.

The Venetian mimed a gesture of comic despair.

‘To be perfectly honest, I have quite forgotten. It must have been something connected with last night’s business, 33but the sight of this charming young lady has quite driven it from my mind.’

Casanova often fell in love at a glance. His smouldering gaze left Chiara quite disconcerted. Her fingers toyed nervously with a flower of gold that she wore about her neck. Volnay noticed, and felt a rush of anger at the Venetian. He thought of a stratagem to rid himself of this unwelcome visitor. He invited his guests to sit in his two armchairs, and seated himself on a stool. Pleasantries were exchanged about the late coming of spring.

‘You are a lover of science, Mademoiselle,’ said Volnay, suddenly. ‘Madame d’Urfé’s laboratory will certainly fascinate you. They say it is crammed full of stills and jars of every kind, with a furnace that is kept burning even through the height of summer. Madame d’Urfé has been working there night and day for years, in hopes of discovering the elixir of life. The Chevalier de Seingalt here is sure to know all about it.’

Casanova raised one very aristocratic eyebrow, feigning incomprehension. Chiara D’Ancilla turned to address him.

‘Whatever does our friend mean?’

‘I haven’t the faintest idea. Though I have indeed met Madame d’Urfé, of course…’

Volnay gave a thin smile.

‘And extorted money from her on the pretext of initiating her into the mysteries of the Kabbalah!’

The Venetian jumped to his feet.

‘You cannot say that, sir! I have never received so much as a penny from the lady, I give you my word of honour!’

‘Gemstones, to be precise,’ insisted the policeman.

‘Oh, that…’

Casanova affected a gracious wave of the hand.

‘I used them to show her the constellations…’ 34

Chiara was unable to suppress a loud giggle. Volnay turned to her, furiously.

‘Does it amuse you to think of swindling a fifty-three-year-old lady? Do you believe the Chevalier de Seingalt, here present, behaved in a manner befitting his freshly bestowed title when he told the poor, credulous woman that she would become pregnant, die in childbirth and be reborn sixty-four days later?’

Chiara pressed her hands to her chest, struggling unsuccessfully to contain her laughter.

‘Did you really tell the lady that, Chevalier?’

The Venetian gave an exasperated sigh.

‘How the devil did you hear about that, Volnay?’

The inspector sat impassively, in silence. Casanova turned to Chiara D’Ancilla and saw straightaway that she found the story greatly amusing.

‘You shouldn’t mock the Marquise d’Urfé,’ he said indulgently. ‘She was the mistress of the regent, and he is passionate about alchemy. They say he was conducting his experiments with the express aim of meeting the Devil himself! The marquise is researching the balsamic properties of plants, to create an elixir of life. It’s an obsession with her. A harmless enough obsession if it weren’t for her private genie.’

Chiara’s hilarity increased. Volnay was transfixed by her charming lips, chilled by a secret horror that he might see them offered to another.

‘Yes indeed,’ Casanova continued enthusiastically, ‘she has a genie who talks to her at night! He’s thoroughly well intentioned, and advised her to elicit my help in securing the passage of her soul into a male child born of the philosophical coupling of a mortal man with a divine female being. She was even prepared to poison herself to that very end! I dissuaded her…’ 35

He broke off with a modest smile, as if expecting to be congratulated.

‘If I had been thoroughly honest,’ he continued, with aplomb, ‘and assured her that her ideas were absurd, she would never have believed me. And so I thought best to go along with her, for her own safety. But I formed no plan whatsoever to rob her of her riches, though I could have done it most easily, believe me, if I had been in any way ill-intentioned.’

‘And how did you “go along” with her?’ asked Chiara, wickedly.

Casanova fixed her with a penetrating stare.

‘I developed a theory, according to which we would achieve union with the elementary spirits by engaging in hypostasis. The Marquise d’Urfé was eager to carry out the experiment, in order to bear a miraculous child, in which form she would be reborn. This would help her overcome her absurd fear of death!’

Volnay gave an exasperated groan.

‘Her children have filed a complaint: there’s more trouble ahead for you, dear Chevalier.’

Chiara D’Ancilla turned to the Venetian, to scold him.

‘You have made me laugh, but I cannot approve your actions: robbing a poor woman who has taken leave of her senses!’

Casanova’s face lit up with a mocking smile.

‘Robbing her? The lady is vastly rich, and a miser. Securing a few gifts for myself won’t ruin her. Those who have money distribute it to those who do not—it’s a very good system. It’s my belief the rich should be subject to taxation, and the proceeds distributed to the poorest in the land, rather than the opposite, as we do today.’

Chiara smiled affectionately.

‘Well, hark at you.’ 36

‘Her money should go to her children,’ grumbled Volnay, ‘not to you!’

The Venetian’s smile froze on his lips.

‘It will go to her offspring minus a few baubles, rest assured. And her stupid, stubborn children will be a little less rich and fat as a result, Monsieur, the great defender of the rich and powerful of this world! I have no employment, hold no office, as you know. My freedom is unconstrained. All I have are women to love, and the purses of others to spend. Allow me that privilege, at least.’

‘A dubious privilege indeed,’ growled Volnay.

Casanova shot him an icy look.

‘What am I to do? I’m a man of considerable merit, but I live in a century where such things go unrewarded.’

‘Casanova, the great, misunderstood genius.’ Volnay’s response was heavy with irony.

‘Chevalier de Seingalt, if you please.’

‘Your name is not Seingalt, it’s Casanova!’ objected Volnay. ‘The latter is true, the former is false.’

The Venetian responded with a gesture that suggested the conversation was beginning to bore him.

‘Both names are as true as I’m sitting here talking to you now. The alphabet belongs to everyone, as far as I am aware.’

‘You have no more status than a stage valet,’ said Volnay scornfully.

‘Watch your words,’ said Casanova, losing none of his sangfroid. ‘Many’s the stage valet who ends up beating his master with a stick!’

He rose and took his leave of Chiara, elegantly addressing a few words to her in Italian, to which she responded most charmingly. Then he gave a stiff nod to the Inspector of Strange and Unexplained Deaths and left.

‘Chevalier de Seingalt! Wait, please!’ 37

Chiara turned to Volnay with a playful look.

‘Forgive me, Monsieur, for leaving so quickly, but I’ve just remembered that I am expected elsewhere. Please consider my request. You are a police inspector—you will know how to find me.’

Out on the street, Volnay watched darkly as Casanova gallantly helped the young woman into her carriage, then joined her. The driver cracked his whip and the vehicle shuddered. Volnay shook his head, trying to rid himself of his black thoughts. It was said that Casanova had raped a young woman in her carriage and that she hadn’t even reported the crime. But then, what woman would dare report such a thing in this day and age?

The chevalier’s pronouncements about money lacked conviction. Casanova was often short of funds, but as the protégé of the abbé de Bernis, the former French ambassador to Venice, with whom he had shared a mistress in Venice, Volnay knew that he had secured an introduction to the Duc de Choiseul. After which, praised by Bernis as an expert in matters of finance (especially the finances of others), he had persuaded the financier Joseph Pâris-Duverney of the infallibility of a plan he had devised, for a lottery. D’Alembert, the mathematician, had been persuaded, too. Casanova had obtained six offices and a comfortable salary of four thousand francs per year to set up the lottery, the aim of which was to finance the new military college, without raising taxes! Since when Casanova had been living in luxury, in a magnificently furnished villa, with a stable of horses, carriages, grooms and a retinue of servants.

Volnay walked slowly back to his house. Again, his thoughts turned to the carriage bearing away the young woman who had awakened a heart imprisoned in ice for so long. Then he thought of the Venetian and sighed.

‘Ah! Casanova…’ 38

He swore out loud. The magpie broke its silence, cackled and called out:

‘Casa! Casa Cretin!’

Casanova studied Chiara’s face as she turned to him. She radiated an unexpected light, just as some paintings of the quattrocento subtly show Mary to be more woman than Virgin. And with that, memories rose to the surface of his mind, in a disorderly rush he had not experienced for many years. First, the face of a mother who never granted him so much as a single loving look. Yet he would have paid dearly, in his childhood, to see his own reflection even for a second in the sparkle of her eyes. Next, the face of Henriette, his dearly beloved, and the message she had left him, carved on the windowpane with the point of a small diamond she wore in a ring: ‘Henriette shall be forgotten, too.’ Twelve years had passed, and he had forgotten nothing. He half closed his eyes, allowing his feelings to subside and his carapace to shut tight once more. He was alone with his memories. There was nothing to be gained as a lover of women.

‘Why were you in such a hurry to leave Volnay?’ he asked.

‘Because he was in too much of a hurry to chase away one of my countrymen, and doubtless for the wrong reason.’

‘Really?’ he asked, innocently. ‘And what reason is that?’

She stared him straight in the eye, discovering all the Venetian’s legendary vitality as she did so, concentrated in his gaze.

‘A reason I’m sure you can guess.’

Casanova allowed an amused smile to flutter at his lips. This young woman was vivacious indeed, and very sharp.

‘And what about you, Chevalier?’ she went on. ‘What brought you to visit the inspector? Have some young girl’s parents filed a complaint?’ 39

Casanova looked slightly annoyed. The fact was, he had been thinking all night about the faceless woman, and the letter that Volnay had removed from her body. His mind, ever alert to the possibility of securing some advantage in life, told him that this was fertile territory, worth exploring. The inspector must have taken the letter for good reason. From what he knew of Volnay, he was a man of integrity. Was he trying to protect someone? The affair was worth a closer look. Often enough, knowing all there was to know had helped him keep body and soul together: one reason why he had called on the Inspector of Strange and Unexplained Deaths. But this young woman had distracted him from his purpose.

‘A simple courtesy call,’ he replied, and said no more.

Chiara laughed.

‘A courtesy call to an officer of the police—a rebel like you!’

‘Me, a rebel?’ Casanova was astonished.

‘You’ve been in prison; you escaped. You don’t care a jot for the law, you have dared to revolt against authority!’

Her eyes were so bright with excitement that the Venetian was loath to disappoint. But some reputations were best not lugged across Europe in a man’s baggage.

‘I am no threat to society, Mademoiselle.’

‘And yet you challenge it, by not living according to society’s conventions!’

Casanova watched her attentively. He was seldom seen as a man at war with his own time. He had no bone to pick with anyone, though he enjoyed duping the gullible, and making a mockery of the law. And yet no one on earth was freer than he: he loved women madly, but when pushed he would always choose his freedom.

‘It is true that I often pass from Their Royal Highnesses’ courts to their prisons,’ he admitted, elegantly. 40

She chuckled, and again he enjoyed her refreshing laughter, a reminder of Venice and more carefree days. What is beauty? he wondered, observing her with rapt devotion. We cannot say, and yet we know it in our hearts.

‘Why did you take the name Seingalt, which seems to annoy our friend Volnay so?’ she asked him suddenly.

‘Oh, that’s very simple,’ he said, with a twinkle in his eye. ‘Seing means “signature” and alt is short for altesse: Highness.’

She looked at him, and her expression was grave once more. The Venetian’s insolent disregard for society as a whole was enormously pleasing.

‘How did you become what you are, Chevalier de Seingalt?’

‘I grew up surrounded by women, from infancy,’ he replied, in a tone of sincerity that surprised even him. ‘That certainly influenced me in some way, for I have always loved the opposite sex, and have made sure to be loved as much as I was able.’

She leant forward, intrigued. Immediately, he was enveloped in her wonderful scent. He breathed it discreetly, alert to its elegance and sensuality.

‘Tell me about that, Chevalier.’