Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Heliotrope Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

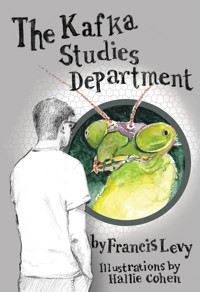

From Francis Levy, author of Seven Days in Rio, which The New York Times called "a fever dream of a novel," comes The Kafka Studies Department, a highly original collection of short, parable-like stories infused with dark humor, intellect, and insight about the human condition. While the book's style is deceptively simple and aphoristic, it carries a hallucinatory moral message. A prism of interconnected and intertwined tales, inspired by Kafka, the stories examine feckless central characters who are far from likable, but always recognizable and wildly human.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 106

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for Francis Levy’sThe Kafka Studies Department

“Knowledge is not power, power is not power. Life is irrational or accidental or both. We drift victims, victimizers. A collection for our time.”

—Joan Baum, NPR

“Francis Levy has an unhampered, endearingly maverick imagination—as if Donald Barthelme had met up with Maimonides and together they decided to write about the world as it appeared to them. These deceptively simple and parable-like stories are full of wily pleasures and irreverent wisdom about everything from the failure of insight to make anything happen, to the subtle gratifications of friendship, to the tragicomedy of eros.”

—Daphne Merkin, author of This Close to Happy and 22 Minutes of Unconditional Love

“A collection of bleak and amusing literary short stories from Levy...A dark, sometimes funny, meditation on the absurd trials of life.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Francis Levy’s fiction is knowing but never instructive. His characters inhabit a twilight zone where the lines blur between dream and waking, familiar and surreal, inevitability and surprise. These short takes, snapshots of feelings-in-flight, of moments still being formed, build an irresistible magic. I found myself enchanted.” —

Rocco Landesman, Broadway producer and former Chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts

“The Kafka Studies Department is not about academia. It’s about anomie, and how complicated it is to figure out what’s really going on with people. Of course (since it’s Levy) it’s about sex. Kafka’s shadow is everywhere as Levy’s characters stumble their way through their compromised lives. The interlinked stories leap across time and context, in satisfying and sometimes hilariously poetic ways.”

—David Kirkpatrick, journalist and author of The Facebook Effect

“A startling collection of thirty literary gems deftly illustrated by Hallie Cohen into dreamy sketches, which perfectly suit the tone of the work. Initially it seems like these stories are fed into a kind of a magical Kafka Cuisinart where they come out tightly sealed, hilariously ironic, and occasionally mysterious. On the surface they have the muted highbrow narrative of Wes Anderson movies. On a closer look you’ll find they are actually far more nuanced and layered. To a lesser writer, they could easily bloat to ten times their size. This economy though, allows for the reader to reflect on each piece—many of which unravel as modern parables that have the makings of mini-masterpieces.”

—Arthur Nersesian, author of The Five Books of Moses and The Fuck-Up

Praise for Francis Levy’s Seven Days in Rio

A fever dream of a novel.”

—New York Times Book Review

Praise for Francis Levy’s Erotomania: A Romance

“Sex is familiar, but it’s perennial, and Levy makes it fresh.” —Los Angeles Times Book Review

“Levy seems to have an eye for detail for all that is absurd, commonly human, and uniquely American.” —Bookslut

© 2023 Francis Levy

Illustrations ©2023 Hallie Cohen

Published by

Heliotrope Books,

New York, NY

All rights and publicity information: [email protected]

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher, except brief passages for review purposes.

First printing 2023

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-956474-27-5

Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-956474-29-9

E-book ISBN: 978-1-956474-28-2

For Dr. Kafka

Thanks to Christopher O’Brien and Michael Dwyer for their sage publishing and design advice and thanks to John Oakes of Evergreen Review for his suggestions and support. I am also grateful to Louise Crawford and Linda Quigley who brought this book into the public eye, to Naomi Rosenblatt of Heliotrope Books for her support and guidance, to Lauren Cerand for her encouragement and to Adam Ludwig for his attention to structure and detail.

Contents

The Kafka Studies Department

The Sprinter

As I Lay Down

The Healer

The Book of Solitude

Profit/Loss

Critical Mass

Happily Ever After

Trust

The Awakening

Company History

The Night Man

Collectors

Imagination

Radio

The Young Wife

Breasts

Falling Body

A Splendid Dish

The Heavy

Sleep

Out of Sight, Out of Mind

Years

Thrilled to Death

Winter Light

Good Times

The Pill

Hit List

The Dead

The Afterlife

About the Author and Illustrator

TheKafka StudiesDepartment

The Kafka Studies Department

All the faculty of the Kafka Studies Department were withdrawn, retiring individuals who’d had troubled relationships with their fathers, and hence authority, all their lives. When you met these rail-thin, bespectacled creatures, most of whom lived alone in the kind of off-campus housing usually reserved for graduate students, there was little question how they had found their master. But the whole is sometimes greater than the sum of its parts. The mere fact of a department devoted to the study of Franz Kafka—the only of its kind in the country—had attracted international attention.

The Kafka Studies Department was perpetually at odds with the university. Someone had to raise money; someone had to deal with an administration more interested in enrollment than excellence; someone had to handle the real world.

None of these gentlemen had the least ability to cope with life. So when the letter arrived announcing a severe cutback in funding, no solution was proposed. Yes, it was a blow at a time when the department’s fine reputation should have put it in an exalted position, but no one dared speak up; no one knew how. Further, it was Kafkaesque. The administration was simply an illustration of the irrational malevolence of The Trial. They would watch the department deteriorate. Life was imitating art.

There were two students who stood out in the class that entered the year the Kafka Studies Department suffered the cutbacks that threatened its very existence. Martin was your typical Kafka scholar. Painfully shy, with a receding posture that made him look hunchbacked, his mocking sense of humor barely veiled his estrangement from life.

Alfred was his total opposite. The Kafka Studies Department had never had a student like Alfred. He was a magnetic personality who’d parlayed his BA in Germanic Studies into a Fulbright and then a series of business ventures that made him a wealthy man—at least by the standards of the Kafka Studies Department. Where most of the students and faculty were celibate, Alfred had a beautiful Valkyrie of a wife, whom he dressed in exhibitionistically sexy outfits. He made no secret of the fact that he wished his wife to look like one of the prostitutes who hung out at night on the edge of campus and whose services he solicited on his way home from the rare book library.

Martin had everything in common with the men he was studying under. But being self-haters, they were particularly dismissive of him. They preferred Alfred, who was everything they weren’t. Martin would come by his advisor’s office to hear Alfred’s arch voice. He would see Alfred’s crossed legs through the half-opened door, an expensive Italian loafer dangling lazily off one of his feet.

Before Martin could even prove himself, Alfred was helping his professors develop a proposal for the National Endowment for the Humanities. He had also fomented a love affair between a beautiful Dostoevsky scholar he’d taken to the track and his mentor, an emaciated looking five-foot five-inch Czech whose PhD was an analysis of Kafka’s “A Hunger Artist.” Totally ignored in his attempts to get even a modicum of attention, Martin began to founder. When it was time to meet with his advisor, he’d pick up on the distractedness of the man and garble his words. His only paper of the year, an attempt to link the expressionist painting of Edvard Munch to Kafka, had been a self-fulfilling failure. Munch and Kafka had little in common. Everyone knew it was Munch and Strindberg. Yet he couldn’t stop himself. The negative attention, the humiliation was more satisfying than a conformity which would have condemned him to live in the shadow of his lusty colleague—whose very life, a series of manipulations, seductions and chicanery, was an affront to everything Kafka stood for.

Then one day, midway in the three-year course, Alfred died. It was that simple. One week he had appeared in class pale and disheveled, the next month he was no more. Apparently Alfred, cocky and confident of his power over life, had ignored the warning signs of the fast spreading cancer that would ultimately kill him. The German word schadenfreude, which often appears in the Freudian canon, means the enjoyment of other people’s suffering. Such was the hatred Martin had felt that in the final weeks, as life seeped out of Alfred, he allowed himself to thrive as he never had before. It was as if the blood were flowing out of Alfred into Martin. The more the once cherubic wheeler-dealer was diminished by his illness, the stronger, more decisive and more physically imposing Martin became. He learned to stand up straight.

In Alfred’s final days, Martin even met a woman with whom he embarked on his first affair. It was as if a huge weight were removed from his shoulders. By the time Alfred died, Martin’s fortunes were already on the rise in the department. Within six months Alfred had been all but forgotten and, driven by an almost mystical energy, Martin had been transformed. Where Alfred employed a crude cunning, Martin’s energies were characterized by a sense of equanimity and cultivation that far outdid his predecessor. Martin was really putting the Kafka Studies Department on the map and he was winning the attention he had never been able to get before.

The professor who had flunked him on the Munch paper even admitted he might have been hasty. Perhaps there was a connection, he said.

But Martin, having no more need for such futile stretches of the scholarly imagination, politely declined the invitation for a review. No sir! He was interested in power. The way you got it was to play the right hand. Martin was on his way. During this time, he began a romance with Alfred’s widow that eventually led to marriage.

One of the items they came across when they were cleaning out Alfred’s closet, so Martin could move into the wonderful house Alfred had built, were the very loafers Martin had spotted through the crack in his advisor’s office door. Just as his lovely new wife was about to toss them into a plastic garbage bag, he cried “Stop!” He took off the cheap Hush Puppies of the impoverished scholar and tried on one of his deceased rival’s cordovans. It fit perfectly.

That same day Martin sat facing his advisor. He laughed to himself, one of the loafers dangling lazily off his foot, as the shadow of the insecure first-year graduate student he had once been approached the half-opened office door.

The Sprinter

One day the sprinter appeared on Rockland Avenue, a hilly winding road off Weaver Street in Larchmont. There were lots of runners on Rockland Avenue. Practically all the families that occupied the split-level, Tudor, or colonial style houses which lined the street had children or adults who ran—sometimes both. But from the first, it was apparent the sprinter was different. He had a chiseled face and grotesquely muscular torso. His forehead was perpetually beaded with sweat from the ferocious workouts he put himself through.

Most everyone knew everyone else on Rockland Avenue, and after the sprinter had shown up every day for a week, neighbors started to ask each other about him.

“Looks like someone training for something,” remarked one.

“It’s starting to get on my nerves,” said another.

It was only when the sprinter’s breathing turned into a wheeze as the length of his workouts extended into the evening that some people on Rockland began to think something ought to be done. For weeks on end, rain or shine, the sprinter had not missed a day. He always wore the same tight blue spandex shorts, Golden Wok tee shirt, weightlifter’s belt, aerobic shoes, and white tennis headband. There was no variation in his dress or routine, except for the fact that he seemed to be running himself a bit harder each day. And, indeed, every day his frame grew more thin, his jawbone more pronounced, and his eyes more filled with cold determination as he put himself through his grueling paces.

None of those who thought something should be done knew exactly what to do. Though the sprinter’s breathing could be heard like clockwork, it could hardly be called disturbing the peace. Everyone was into physical fitness; there were all kinds of bizarre regimens. You couldn’t call the police because the sound of someone’s jump rope hitting the pavement was bothering you. The kiais