Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

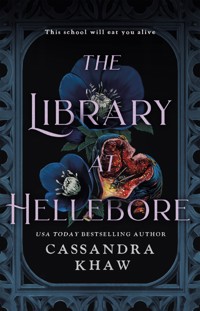

Dark academia meets cosmic horror in this murderous tale of betrayal and broken hearts at an elite academy for the gods and monsters of the world, perfect for fans of The Atlas Six, If We Were Villains and Bury Our Bones in the Midnight Soil. The Hellebore Technical Institute for the Gifted is the premier academy for the dangerously powerful: the Anti-Christs and Ragnaroks, the world-eaters and apocalypse-makers. Hellebore promises redemption, acceptance, and a normal life after graduation. At least, that's what Alessa Li is told when she's kidnapped and forcibly enrolled. But there's more to Hellebore than meets the eye. On graduation day, the faculty go on a ravenous rampage, feasting on Alessa's class. Only Alessa and a group of her classmates escape the carnage. Trapped in the school's library, they must offer a human sacrifice every night, or else the faculty will break down the door and kill everyone.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 376

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Before

Before

Before

Before

Day one

Day one

Before

Before

Day one

Before

Day one

Before

Day one

Before

Day two

Before

Day two

Before

Day two

Before

Day two

Before

Day two

Before

Before

Day two

Before

Day two

Day two

Day three

Before

After

Acknowledgments

About the Author

“This is punk rock, eldritch god, carnage-fueled battle royale dark academia. The Library at Hellebore is more metal than I’ll ever be and too cool for most of you.”

Olivie Blake

“Wonderfully inventive and thoroughly engrossing. Khaw takes dark academia to a terrifying new level.”

Kelley Armstrong

“As rich and gruesome as a fresh-plucked heart, as sharp as a broken bone, The Library at Hellebore is a perfect horror novel by one of my favorite writers. It’s a book that draws a line between the monsters and the monstrous, and reminds us who to root for—and what it costs.”

Alix E. Harrow

“A kaleidoscopic spectacle of gothic surreality and absurdity. It is body horror in all its glory, exploring the numbing exhaustion of loss, along with the seductive pleasures of death.”

Ai Jiang

“A gorgeous, gory shuddering heart of a book! Khaw’s prose and storytelling remain god-tier!”

Katee Robert

“A horrifying tale with lush and gorgeous prose you can sink your teeth into.”

Monika Kim

“A joyfully gory spin on the magical school.”

Kendare Blake

“Devilishly entertaining, thrillingly structured, and full of unexpected blows to the heart.”

Nat Cassidy

“Pure, bloody darkness beautifully lit up with fury, sacrifice, and revenge.”

Premee Mohamed

ALSO BY CASSANDRA KHAWAND AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

Nothing But Blackened TeethThe Salt Grows Heavy

ALSO BY CASSANDRA KHAWAND RICHARD KADREY

The Dead Take the A Train

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Library at Hellebore

Trade edition ISBN: 9781835414125

Black Crow edition ISBN: 9781835417140

E-book edition ISBN: 9781835414132

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: July 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Zoe Khaw Joo Ee 2025

Zoe Khaw Joo Ee asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

EU RP (for authorities only)eucomply OÜ, Pärnu mnt. 139b-14, 11317 Tallinn, [email protected], +3375690241

Typeset in Fournier MT Std.

For Farrell, who is not mine but a good catand has been his whole life.And for Sebastien Fanzun, scholar and cat personand my first friend in Zurich.

TheLibraryatHellebore

Before

When I woke up, my roommate, Johanna, was dead.

This was neither the first time I’d come to with a body at my feet, nor was it even the first time I had returned to consciousness in a room transformed into a literal abattoir, but it was the first time I woke up relieved to be in a mess. The walls were soaked in effluvium. Every piece of linen on our beds was at least moderately pink with gore. The floor was a soup of viscera, intestines like ribbons unstrung over the scuffed wood; it’d been a deep gorgeous ebony once, but now, like the rest of our room, it was just red.

Carefully, I reached for Johanna’s outflung arm, the one desolate limb to have survived what happened to her, and folded it over her chest, closing my hands over her knuckles. She was still here. There were even parts I could recognize. When it struck me, I thought I’d wake up and none of what I did would have mattered, that her body would be missing. But she was still here. It wasn’t much but it was something. I’m not religious in any sense of the word. Far as I’m concerned, dirt’s the only holy thing in the world. It can make roses out of even the worst losers: in death, we achieve meaning. I stared at the mess. While I could give a dead rat’s rotten lungs about divinity, I had a lot more compassion to dole out when it came to the dead—especially when the deceased in question was someone I’d just achieved character growth with.

It wasn’t fair.

Being sad, however, wouldn’t rewrite the past to give us a platonic happily ever after, although I imagine if I got her necromantic situationship involved, that might change things. Part of me thought about it. Let’s be clear about that. Part of me did think about looking for Rowan, about demanding that he see if there was anything that could be done. Johanna had been nothing but kind to me, after all. The fact that she was weird and codependent about it was beside the point. Even in my worst moments, she had cared.

Pity she needed to die. Pity she needed to stay dead. Pity all that was as inevitable as what was coming next.

“Alessa?”

I turned to see a lithe young man at the door. Rowan was thin in the way most smokers eventually became, gristly and lineated with veins, his skin already like a piece of dehydrated leather. But there was an unconventional appeal to his Roman nose, his mobile lips, the eyes like flecked chips of lapis. His expression was affable, unbothered. You’d think he would look more troubled. Johanna was kind of his girlfriend.

Then again, this was also Hellebore. But we’ll get to that.

“Good morning,” I said. “I can explain.”

“Is that so?” said Rowan, his gaze making a circuit across the mess, a single line indenting the space between his fluffy eyebrows. Mine felt matted with blood but it didn’t feel like it was appropriate to check. “I’d really like to hear it.”

“Yes, well.” I took a breath. A glob of something lukewarm traveled down the bridge of my nose. “Actually, that’s a lie. I can’t really explain it. Scratch that. I was asked not to explain it. So, that makes things … difficult.”

“More difficult than being caught committing homicide?” The lanky boy crossed the room to where I stood beside Johanna’s corpse, one of my hands still clasping hers. A smile crept up to his mouth, wary as a beaten animal.

“Lots of judgment from someone who was just a fuckbuddy.” His sanctimoniousness drew an unexpected venom from me. “I thought you didn’t care about her.”

“I cared about her as a person.”

“If you did, you’d have left her alone.” Cruelty was like riding a bike: it became ingrained in you, became muscle memory. There was no losing the trick of it. You never forgot how to drive a knife in and twist. “She loved you, you know.”

He flinched like I’d punched him.

Good, I remember thinking, a tang of bloodlust slicking my tongue.

“If you knew what I knew, you’d have treated her better. I take that back. If you knew what I knew, you’d have stayed the fuck away and left her alone.” I spat the last word. “You used her.”

Rowan stopped about a foot from the steamer trunk in front of Johanna’s bed, his knee bumping into the verdigris lid, and tipped one hand at me, turning it palm up. He was the very image of good faith, earnest and smiling. He looked like I’d just anointed him with compliments; there was something almost coy in the way he peered at me through long black lashes.

“Be that as it may,” he said. “That doesn’t change the fact you killed her.”

“Well, I didn’t want to.”

It wasn’t a defense. I knew that. Neither was the shrug I offered up, my gaze falling again to Johanna’s remains. Even defiled thus, her golden hair was somehow unmistakable. Same with the perfect curve of her jaw, dislodged as it was from the rest of her skull. What surprised me though was how much it hurt to see her dead.

“There is gunk coming down from the ceiling,” said Rowan after a minute of obtrusive silence.

I looked up. As it turned out, there was.

“That wasn’t intentional.”

“Alessa, just tell me what happened.”

The coppery, sweetly fecal smell of death was beginning to intensify.

He reached out with a gloved hand, desperation pushing up against that smiling facade, the nonchalance faltering, cracking under the pressure of what I could assume to be grief. For a second, I was witness to the fatal loneliness at the core of that grinning, jocular, often inappropriate boy—to the child who must have spent his early life up to his ears in protective gear so as to prevent him from rampant manslaughter. They say that babies can die from touch starvation. I wondered what Rowan had had to kill to be standing here now, what he had had to give up, all to be too late. I wondered if some part of him had died at the sight of Johanna’s remains, knowing there laid butchered most likely the only woman who’d ever look at his deficiencies and still see him as enough.

“Please,” said Rowan.

Before I could say anything, another voice broke through the air.

“What did you do?”

We turned in tandem to see a figure stumbling fawn-legged toward us, pausing at intervals to flinch at the charnel, the color bleeding from a face already arctic in its complexion. Most people would call her a beauty and they’d be right any other day. There and then, however, she was a car crash in slow motion, that long, drawn-out, honeyed second before an explosion. She was a corpse that hadn’t caught up to the fact that her heart had been dug out and eaten, dripping like a fruit. In her face, a kind of obstinate hope somehow. Like if she lived in this incredulous grief for a little longer, it’d grant Johanna a Schrödinger’s immortality: keep her not necessarily alive, but not dead either.

“What did you do?” Stefania screamed.

A little to my surprise if not Rowan’s, she arrowed straight toward him, literally serrating as she did: every limb began to split into outcroppings of teeth, skin becoming stubbled with molars, speared through with expanding incisors. Her face bisected and then quartered, petaling, each flap lined like the inside of a lamprey’s mouth. When she screamed again, it was with a laryngeal configuration that had no business existing even here in the halls of Hellebore: it was a choir, a horror, a nightmare of sound.

“You,” she said in all the voices those new mouths afforded her. Tongues waved from every joint. “You fucking bastard.”

Rowan threw his hands up, backing away, even though I was the one smeared with a frosting-thick coat of gore. “First of all: fuck you. Second: how dare you? The visual evidence alone, Stefania. It’s clear—”

Whatever else he might have said was swallowed by an obliterating white light. The incandescence lasted only for a second but it filled the room, burning away all features. Then it winked out and as our sight returned, we discovered collectively there was now a fourth member of our little tableau.

Standing before us was the headmaster herself, bonneted and in a cotton nightdress ornamented with smiling deer. Though the style was cartoonish, it did little to whet the absolute horror of the sight: ungulate faces were never meant to stretch that way. The headmistress blinked owlishly at us, her eyes magnified by the lenses of her horn-rimmed spectacles. I froze at the sight of her. I knew what was behind that doddering facade.

“Children.” Her voice when she wasn’t orating was high and breathy, a bad idea away from being babyish, like a sorority girl courting the quarterback’s attention. It was particularly weird coming from someone who looked and acted the way the headmistress did: namely, old. “What are you doing?”

“What,” said Stefania, devolving back to her usual shape, a process that involved more slurping noises than I would have preferred. “Headmaster?”

“This is terrible behavior.”

“They killed my friend,” exhaled Stefania, and the helplessness in her voice was worse than her rage, a note of keening under those panted words. “Headmistress, please—”

“There is a soiree waiting for you,” continued the headmaster, putting undue emphasis on the word soiree, dragging out the vowels, turning them nasal, exaggeratedly French. “You should be dressing up. You should be putting on makeup.” Her eyes darted to Rowan. “Better clothes. Why aren’t you working to look delicious?”

In movies, it is always clear when the villain slips up with a double entendre. The music score changes; the camera pans in on their faces. It is a narrative design, a conspiratorial glance at the audience: here is the signage marking the descent into mayhem and here too, the strategically positioned lighting, placed just so to ensure no one ignores the moment. But with the headmaster, it was clear the use of those words was deliberate. She did not speak them in error. This wasn’t Freudian. This was her telling us that she expected us to look pretty on a plate. The audacity left me speechless, but not Rowan.

“I’m afraid I taste terrible,” he said, flapping his hands. “Like, absolutely rancid. Between all the smoking and drinking, it’d probably be awful. Just awful. Can I help with the drinks instead?”

“You’re insane,” said Stefania. “I refuse to be part of this.”

The headmaster didn’t even look at her. Instead, she said sweetly, “In that case, I suggest you hang yourself.”

“You mean it,” I said after a drawn-out moment. “You’re actually planning to eat us.”

“I said make yourself look delicious,” trilled the headmaster, twirling a mauve-veined hand at me. “You’re the one coming up with questionable conjecture.”

But the look in her eyes said everything, as did her delicate smile. Rowan swallowed the rest of his rambling excuses, his jaws clenched so hard I heard the scrape of enamel as they ground together, and Stefania stared at the floor with a furious, indiscriminate hate. I studied the headmaster, wishing I had a rejoinder that didn’t make me sound petulant. My only consolation was that the epiphany of this impending cannibal feast had both Rowan and Stefania at least temporarily distracted from the ugly business of our dearly deceased mutual friend.

Her smile deepened. She knew as well as the three of us did that there wouldn’t be opting out of the situation.

“You can’t make us go,” said Rowan.

“Actually,” said the headmistress, voice losing its chirping lilt. She spoke the next words in what I’d come to think of as her real voice: smooth and bored, unsettlingly anodyne save when her amusement knifed through the surface like a fin moving through dark water. “I can.”

Before any of us could object, the world spun and, sudden as anything, we were in the gymnasium. Each and every one of us were in formal raiment, a mortarboard jauntily set at an angle on each of our heads. We were as pristine as if we’d spent the day in frenzied ablution: hair shining like it’d been oiled individually, faces beautiful. We looked like we were waiting backstage for our turn on the catwalk—like sacrifices, or saints waiting for the lions.

The air had an odd crystalline shine to it like it had been greased somehow. That or I was in the throes of a migraine. It was hard to be sure. I’d been plopped next to Gracelynn, who was sat between Sullivan and me, with Kevin on my opposite side. Bracketing us was a pair of twins I’d only seen occasionally but knew by reputation, the two notorious for the ease with which they procured reagents for whoever had the money to pay: they could get anything so long as what you wanted came from something with a pulse. A few familiar faces were past them to the right: Stefania, Minji, Eoan, and Adam, who slouched almost entirely out of his seat.

“What is going on?” Kevin hissed to me.

“We have to go,” I said in lieu of an answer, standing.

The world stuttered.

I was back on the metal fold-out chair I’d been sitting on, like my muscles had changed their mind midway to rising. Except I hadn’t felt myself sit back down. Instead, it was more like the seconds had rewound, had flinched back from my decision like it was a hot stove. I tried again. This time, I felt it: reality slingshotting backward through linear time, not far enough to leave me discombobulated, but enough to have my ass on the cold, cheap steel. It hit me then that I was trapped. All my efforts, all those months spent trying to get out, and here I was with no place to go, a bunny with the hounds gathered all around.

The doors of the gymnasium opened, allowing our headmaster entry. She drifted down the aisle, splitting the crowd of so-called graduates, resplendent in a fawn-colored suit, the majesty of which was spoiled by the fact that her white hair was still in curlers. A clipboard was tucked in the crook of her left arm. She checked something off as she passed each student, her smile as it always was: slightly too wide for her face.

When she finally reached our row, she only said, with an effervescent giggle:

“Ah. It’s time for a speech by the valedictorian!”

Sullivan took her hand when she offered it. I couldn’t help the “No, stop!” that wrestled out of my mouth. I groped for Sullivan’s arm, the motion entirely reflexive. He and I, we weren’t close, but some animal instinct roared past all my other sensibilities. I knew unequivocally that if he went with her, he would be dead.

“Sullivan—”

He unbraided my fingers from his wrist, a suicidal gentleness in his eyes as he said, “It’s okay.” His eyes shifting to Delilah—his light, his lamb, his death. She wouldn’t meet his gaze, stared instead into her palms, more statue than girl.

It definitely wasn’t.

Before

If you’re reading this, there’s a small chance you’re another student, frightened senseless (been there) by a waning belief (sorry, this book won’t make this better) that you are in a safe place; but more likely, you are an incumbent in the Ministry, and therefore are already aware of what the Hellebore Technical Institute for the Ambitiously Gifted is (fuck you very much, if you are). On the off chance that you’re neither, that you’re a bystander who found my journal in an antique store, or someone raiding the evidence locker for novelties, I want to set the stage before we get any further.

Magic is real.

I want to assert that I know you probably know this already. We do both live in a world where even governmental bodies have acknowledged magic’s existence. But we reside as well on a planet where the efficacy of medical science is questioned and media personalities argue whether a clot of cells has more value than a woman’s life. To put it another way, these are unutterably stupid times, so I’m not taking chances.

Now, while magic has always been real, there was a period when it thrived. For better or worse, people were once steered by folklore—cultivating gods, curating herbs based on their value in rituals, the works. Back then, population density was low enough that myths could breed in dreams and spring like Venus from the peasant’s skull, ready for mischief. It was the best and worst of times.

That went away with the Renaissance period when society began mass-producing these tender, inquisitive souls: scalpels draped in skin. All they wanted to do was cut the cosmos open and see what was inside. Their joyous and relentless curiosity led to such a revolution in human thinking. We went from soothsayers to science, gods to generating electricity. Our lifespans grew; childbirth stopped being a macabre lottery. We sanded the dark down to a manageable threat; everyone still knew to be cautious when out walking at night, but they were no longer afraid of ghosts, just one another.

Those years of frenzied development, interspaced with decades of war, kept mankind so preoccupied we didn’t notice magic receding from us. One day, it was there. The next, it was entirely fictive, all illusions and sleight of hand, cold reading and con men: nothing a rational person would believe in, let alone practice with any kind of seriousness.

But about a hundred years or so ago, it started coming back.

And chaos immediately ensued.

Like, immediately. Faith healers discovered their snakes now had opinions, many of which were kinder than their own. Relics were demanding their burials, along with a share of what wealth had been accrued through illegal use of their matter. The graveyards woke with barghests and gwisin. Rat kings whispered through the walls. The housing market collapsed as hauntings drove tenants to paranoia. Psychiatrists were initially delighted by the prodigious business but then discovered that their clientele weren’t all human and weren’t all there for simple conversation. Statues wept; no one would sleep for months.

As was customary, the authorities did very little until this plague of global re-enchantment led to a decimation of the workforce. Unable to rest, unable to eat without worrying if their salad would consign them to a lifetime in a fae lord’s service, unable to distinguish loved ones from doppelgängers, people began choosing the ledge, the pill bottle, the train tracks, the gun. Suddenly, it was a problem that needed immediate solving. Capitalism was unsustainable without bodies to feed the machine.

So the nations of the world slammed their figurative heads together, and concluded there was only one recourse available: bureaucracy. Magic was legislated. Foreign entities were subjected to hastily drafted but impressively thorough immigration laws, and municipalities came up with techniques for zoning cursed territory. Within a generation, there was something comparable to order so long as you were willing to squint real hard—and to blame any deviancy on the education systems now instated across the globe.

Everyone, and I do mean everyone, no matter age or nationality, who was gauche enough to show even a mote of magical talent was instantly freighted to the nearest available school for proper processing. The Hellebore Technical Institute for the Ambitiously Gifted is one such academy. In fact, you could argue it is the premier college for such things. Enrollment isn’t guaranteed by proximity. You have to be a specific kind of someone to be inducted here, have to have the type of bona fides that the front page obsesses over and the op-eds love to dissect. Yes, every member of the student body is—how do I say it delicately?—someone with the potential to destroy the world three times over, and still have time for a good long brunch. (Which you’d know, if you were working for the Ministry. I’ve heard the rumors: you handpicked us for the butcher block.)

Here in Hellebore, we are all Antichrists, all Ragnarök made manifest. We are those who are destined to break the chains binding Fenris to his boulder; we are Kalki come riding on his pale horse; the death of Buddha; the vectors of apocalypse, avatars of the end, world-eaters; memetic violence distilled into bodies with badly underdeveloped prefrontal cortexes, like the world’s least impressive tulpa.

Some of us came by our designations through honest means. Take poor dead Sullivan Rivers (How did he die? You’ll see; have patience), for example. Because Sullivan was the first son to be born in fuck-knows-how-many generations, he had found himself the imminent host of the god his foremothers had dutifully screwed since prehistory. Sullivan had practically flung himself through the doors of Hellebore, hoping they’d save him from the cicada voices scratching at the inside of his eyelids. I wonder how pissed his gods were when his skull was trepanned from every direction. (And his family. I bet they loathed losing, if not a son, then a commodity, a prize; he was their fortune, a bargaining chip, something they could leverage. The powerful never like letting go of such things.)

Admittedly, Sullivan’s kind was a rarefied group. Very main character, if you’d like to be colloquial about the subject. Most of the students in Hellebore are more like me. Freaks. Accidents of circumstance. People who might have led innocuous lives if they hadn’t turned the wrong corner at the wrong time. Unfortunates who woke up one day indelibly different for no reason at all, their appetites like a cancer gnawing through their skin, growing until it erupted through their gums as a forest of new maws. Girls who were hurt and who discovered they could really hurt their abusers in return. You’d be surprised how many of us there are in that last category.

(Or not, depending on who you are.)

The first time I learned I had powers was when my stepdaddy decided that the ring on his finger was the master key to every entrance in our household. He slapped me when I said no, unable to contend with the notion that my sense of autonomy precluded his need to be inside where he damn well shouldn’t be. I remember my ears ringing, and his hands locked around my wrists, raising my arms above my head. I remember his mouth along the nubs of my spine, his knee trying to spread my legs wide, and thinking, I need you to hurt.

So I rent him in half: lengthwise and real fucking slow, suspending him in the air so his guts sheeted down on me like a porridgy red rain. I didn’t let him go gentle into that good velvet night, and I took as much time as I’m sure he’d wanted to with me. He squirmed and moaned for hours, begging me for respite throughout, going, Please, Alessa, let me die, let me die, this hurts. When I got bored, I made him amputate his tongue with his teeth and choke on it like a cock.

He was the first man I killed and, as you might have guessed, not the last. Though in my defense, the subsequent deaths were less acts of intentional homicide and more (to put it with some modicum of decorum) the consequences of fatally efficient self-defense. One or two of these cases were definitively punitive in timbre, but the victims were deserving. No should have sufficed as an answer. No should have been taken without interrogation, accepted without need for wheedling or attempts at coercion.

Since they wouldn’t listen, I didn’t either.

Anyway.

I was told by Hellebore’s guidance counselor that such murder sprees were common with girls like me. She was a Swedish woman, lean, small-breasted, often attired in starchy suits in the same sodium white of her hair. She smiled like the expression had been taught to her from a manual, and looked like the first abandoned draft for what would become Tilda Swinton. According to her, what we did was natural instinct, a response engendered by a lifetime spent being waterboarded with systemic misogyny: we were angry and we were acting out.

Hellebore could teach us to be better than our impulses, or so student services claimed. It was what the Ministry guaranteed the world. If you forced me to say one nice thing about Hellebore, I’d give it this: the marketing for the institute is award-winning, Everything that has ever been written about Hellebore suggests it is a place of redemption, a place where the unwanted become the coveted. People dreamt of enrollment. It was the highest possible honor.

No one, of course, said anything about the fact Hellebore sometimes kidnaps its students. My salvation was put into motion with neither my awareness nor my consent. I’d mentioned earlier there were students for whom Hellebore represented escape, an alternative to the killing chute of their lives. But not everyone chooses Hellebore. Many were apparently enrolled the way I was. Conscripted, really. One night, I went to sleep in my shitty tenement in Montreal’s Côte-des-Neiges. The next day, I woke up in the dormitory, primly dressed in plaid pajamas, my hair brushed to a gloss. The bed I occupied was the largest I’d ever slept on, a California king with a wrought iron canopy strung with fairy lights and muslin. The duvet was a stiff enamel jacquard subtly inlaid with gold leaf, the sheets themselves a plain and sturdy cream-colored cotton, and there were more pillows than reasonable, like someone had wanted to build me a cairn of goose down and pewter silk.

None of my belongings survived my transit into Hellebore’s vaunted ranks. Instead of my things, I found steamer trunks—I should have run when I saw the scratched-out name, the B carved over and over into the wood, the mottling along the leather straps; I should have known what they were, the discolorations, the corroded grisailles of dried blood, and run—under the skirts of my bed. Inside were uniforms; Peter Pan–collared dresses (the school had an archaic concept of gender expression) in what turned out to be the school colors, jasper and emerald and oxidized silver; well-tailored suits in the same palette; winter gear inclusive of fur-trimmed capelets; modest heels, walking boots; demure underwear; hats; textbooks; alchemic tools; and magical paraphernalia. Every single item was embossed with Hellebore’s heraldry: fig wasps and the school’s namesake threaded through the antlers of a deer skull, its tines strung with runes and staring eyes.

The first words out of my mouth when I’d inventoried the mess were, “I guess I’m a wizard then.”

I remember laughing myself sick.

What a fucking idiot I was.

Like I said, I should have started running right there and then, and maybe I would have. Maybe I’d have clawed out of those flannel jammies, put on shoes, and bolted amid the chaos of orientation if the situation were even infinitesimally different. If I had been alone that day, with no one but the buttery morning light to bear witness to my escape. But I wasn’t.

A full minute after my histrionics, a timid female voice to my right said, “I guess that makes me one too.”

Before

A small white hand hooked around a fold of my bed’s drapery and began to pull. I caught it by the fingers before it could complete the motion; the skin under my palm was clammy, unnaturally hot, as if a furnace burned under the surface.

“Who?” I began. It wasn’t just the owner of the hand who was fever-warm, but the room itself: the heaters were on at full blast. I could hear steam chatter and clank through a maze of pipes, hissing like a cornered animal. “The fuck are you?”

The hand slid out of mine. A white girl of similar age to me shouldered through the canopy and sat herself on the edge of my new bed, hands set primly on her thighs. She was very blond, very pretty, very much something that made every hair on the back of my neck rise. My skin wanted to crawl down between the mattress and its frame. It was her eyes, I decided, that had so thoroughly upset me. They were wide and green where they weren’t dilated pupil, a noxious and effulgent shade of absinthe. Paired with the docile smile she wore, her eyes made her look like a wolf serving time in the brain of a fawn, a wolf so starved it would eat through its own belly if only it could reach.

“I’m Johanna,” she said meekly. Healing sores dappled the cream of her throat, like bite marks. “I think you’re my roommate, which is not what I was expecting.”

She ended the sentence with a frazzled laugh, both an accusation and an apology in her expression. There was something in her tone I did not like, a thoughtless possessiveness over our current environment that said to me this wasn’t someone who had ever been told no. Johanna wound a hank of golden hair around a finger until the skin of the digit turned white.

“Did you wake up here too?” I said, in lieu of asking, What were you expecting?

“I came here the normal way,” she said. Cathedral windows sprawled over the wall opposite my bed, showing mountain peaks crowned with snow. “Me and my best friend, we applied to be students in Hellebore and were approved.”

“Good for you.”

When I said nothing further, Johanna added: “Her name is Stefania.”

“I didn’t ask.”

To Johanna’s credit, she hardly reacted to my vitriol. If I hadn’t been eagerly looking, I’d have missed the sudden flutter in her mouth and at the corners of her eyes, as if a current had been very briefly run through her, but I was, and it made me grin to see. She was human enough to upset, then. Good.

“So,” she said, too well-bred to be kept on the back foot for long. Her expression cleared and it was like the sun coming out after a thousand years of dark. Her smile should have reduced me to worshipful cinders; it should have made me want to beg forgiveness for being such a hateful little gremlin. Under different circumstances, it even might have. However, I’d been recently kidnapped in my sleep by educators and I was pissed. “What’s your name?”

“Alessa,” I said absently, looking over the room again. A distant bell tolled what I assumed to be the hour. Softer still was a murmur of voices seeping through the pearl-colored walls. “Alessa Li.”

Johanna nodded and freed a small leather-bound notebook from a pocket in her dress, licked the tip of a finger, and began leafing through the water-warped, much-highlighted pages until she arrived at a blank space. She wrote my name down, underlining it twice.

“Is that your full name?” she asked conscientiously.

I stared at her in blunt amazement.

“What?”

My new roommate colored. “East Asian people tend to have more than one name, don’t they? Alessa would be your Christian name—”

“I’m not Christian.”

“Okay, that wasn’t the best choice of word, but you know what I mean.”

I did, but I glared balefully at her instead, happy in my meanness.

“I was wondering,” she said, clearing her throat, “if you had an Asian name too.”

It took me entirely too long to parse her question, so appalled was I at her presumptuousness, and when I did, all I could do was bray with laughter.

“What’s so funny?” she demanded.

“Listen, just listen for a second,” I said when I had the wherewithal to speak coherently again, swabbing the tears from my eyes with a sleeve. “It’s very clear to me that I am the last person you wanted in this room with you—”

“That is unfair.”

“—and you are trying so very hard to be polite,” I continued, inexorable, remorseless as the heat death of the universe. “But with all respect, I don’t want to be here. I don’t want to be your friend. And I damn well don’t want to play twenty questions. Also, really? Do you not think it’s maybe a little bit gauche to ask for someone’s whole and truest name? I have absolutely read up on what people do with such things. Haven’t you?”

The flimsy edifice of her self-esteem broke at last, her smile vanishing like kerosene-soaked paper touched to a flame. She bleated something that might have included the word sorry as she rose, stiff-limbed and sobbing, to totter out of the room.

In her hurry to leave, Johanna left the door ajar, and I watched in silence as the corridor filled with people. A great majority were in their late teens, early twenties; a few anomalies drifted through the throng: sorcerous-looking geriatrics in jewel-hued robes and prepubescents who all but sloshed in their school attire, hems dragging. Most strode past without acknowledging the exposed entryway. Those few who did met my eyes with a mix of disapproval and uncertainty, their expressions ranging from furtive to frightened. It wasn’t until much later that I would understand why that open door was such an egregious sight in Hellebore.

More bells began to sound, deep and mournful. The students increased their pace, all funneling in the same direction. I wonder sometimes what might have happened if I had been kinder to Johanna, or quicker to move, if I had been savvy enough to close the door, hide myself, scale down from a window, do anything other than gawk moronically at the crowd while in plain view of the hall. If nothing else, I think I’d at least have kept my dignity.

“Assembly,” slurred a custardy, rotted voice, a voice that could only have come from lungs that had ballooned with decay and a throat so rimed with bacterial overgrowth it was borderline useless. Yet despite this, the word was spoken with no little volume. It boomed loudly enough to echo through my bones.

My mother used to tell me that in the seventies, there had been a preoccupation with anthropomorphizing food—likely to disguise the fact none of it was very good. The massive figure leering through the doorway might have been a Christmas centerpiece from back then. Its head resembled a child’s papier-mâché masterstroke in all but one way. Whoever had created the thing hadn’t had any paper on hand and so had resorted to sheets of raw muscle instead. It had eyes but no eyelids, a lipless grin of a mouth. It wept lymph as it stared at me, never breaking eye contact, not even as it ducked to enter the room, upsettingly graceful for what was essentially a giant Lego figure crafted of uncooked meat. I screamed. I screamed like a little girl handed a frog for the first time.

“Assembly,” it said again, shambling forward, and that was very much it for my escape fantasies.

* * *

The meat man waited until I dressed before herding me into a vaulted corridor, the ceiling frescoed with dead men swaying from nooses of their own intestines, all hung on the branches of fig trees so heavy with fruit their boughs sagged almost to the ground; with black-haired, blank-faced women who had the eyes and wings of wasps, hovering above labyrinths of books; sweet-faced knights too young and too lithe for their pitted ancient armor; and carnivorous deer. The last was an especially prominent motif. The artist was obsessed with those deer. They had them in every scene. Sometimes, the deer were prey, supine before triumphant hunters, a glory of entrails bared to the eye. Most times, though, the deer were the predators, stalking frightened men through black woods, their muzzles steaming, a red glare in their eyes, which were only pupil.

“The painter was a woman named Bella Khoury,” came a conspiratorial voice in my ear, its timbre low, amused. “Legend has it that she used her own blood to create those.”

I looked over. Beside me, falling in graceful lockstep, was an older girl in an ensemble—she had on at least three layers of finely made, carefully layered tweed—that should have had her basting in sweat but somehow did not. “That so?”

“Oh yes. That part was true. The part that was a lie was that she did it because a man had broken her heart,” said the girl drolly. “Can you imagine? A man inspiring such art?”

I laughed. She laughed. I guessed my companion to be about twenty-five from the soft lines beginning to fan from the corners of her eyes and the edges of her mouth; she carried herself like someone much older, though. The horn-rimmed glasses and slightly myopic stare didn’t help that impression at all.

“Was she the one who came up with the school’s heraldic crest? Seems like her style.”

“I think it was the other way around, actually. She spent the entirety of her time in Hellebore painting the ceilings like she was possessed. After graduation, she purportedly vanished, and the school decided to honor her by incorporating her favorite design elements into the armorials,” said the girl, shedding her glasses to raise them up to a slat of pale light. No dust traveled the beam, which seemed impossible given the walls were drenched in gold-shot, ancient-looking tapestries. There should have been dust everywhere, no matter how vigorous the janitorial staff. There should have been at least some, but against all logic the air remained clean and unpleasantly equatorial.

“Did all this work get her extra credit?” I asked.

“It got her immortalized.”

“Good enough, I guess. What can any of us ask?”

The girl buffed her eyewear on a sleeve, then replaced them on her nose, smiling thinly at me when she was done. She was unreasonably beautiful even with her eye bags, which were the density of neutron stars: she had a face for magazine covers, a profile someone with more smarm might have described as editorial, with its high cheekbones and amused mouth.

“Portia,” she said.

“Is that what they ask for?” I couldn’t help myself, a hint of a flirt in my voice. “Your name? I don’t blame them.”

Her answering melancholic smile had my heart misplacing a beat. “They usually start with your name. Then it gets much worse from there.”

I didn’t have an adequate response for that. Everything I thought of felt too glib, too naïve. Her voice carried a burden of history and it felt then like if I wasn’t careful, the weight of it would crush whatever might be growing between us. The fact I worried about the early death of this small and uncertain thing would surprise me later when I had time to sleep and ruminate on the events of that first day. I couldn’t remember the last time I cared to nurse a conversation like that, couldn’t remember wanting tenderness or ever having any knowledge of its shape. Right then, though, all I wanted was for her to stay.

“I’m Alessa, by the way. Alessa Li. Now that you have my name, we’re even. I can’t do anything to you that you can’t do to me.”

Her smile dimpled along her right cheek. “Shame.”

In lieu of acknowledging that, I cleared my throat and asked, “Are you a teacher?”

“Do I look old enough to be one of the teachers?”

“Recent kidnappee, I’m afraid. I don’t know much except for whatever is in the marketing pamphlets,” I said, making note of our surroundings: the archways feeding into smaller corridors; the many doors and their matching brass plaques; the occasional stairwell, glinting bronze as they spiraled through ceiling and inlaid-tile floor. Hellebore stretched like memory and, like memory, it was imperfect, made of smudged angles and movement at the corners of the eyes. “The teachers could be hot.”

“You think I’m hot?” Her left cheek didn’t quite indent, but it made an earnest attempt.

“I plead the fifth, as the Americans say.”

“I’m afraid American law doesn’t extend here. Hellebore’s a land of its own.”

“Like a country?”

“Like a prison run by secret police.”

“That isn’t worrying information at all. I absolutely wasn’t already concerned about their disinterest in bodily autonomy,” I said as we turned a corner into a new corridor, the walls of which were a deep burgundy where they weren’t polished wainscoting; the trimmings oxidized gold instead of wood, and paneled with yet more paintings. They were everywhere. Whatever else Bella had been, she was certainly prolific.

“It’s not ideal,” said Portia, her smile receding to a thoughtful frown, even as she slowed beside one piece of artwork, this one older, starker than the rest. Students gusted past. “But I like to tell myself that the benefits outweigh the costs.”

“The costs,” I repeated, my regard for her cooling.

Portia seemed to take no notice, her eyes softening as she took in the painting beside us. Gone, the nightmare deer and their soft-faced prey. Gone, the women with their wasp wings and iridescent eyes. Gone, the expansive detailing, the sumptuous foliation of the background, the weird medieval animals in the margins. In lieu of all that, a textured black background, roughly swatched onto the canvas, and the equally rough sketch of a woman, sloe-eyed, furious-looking, standing alone before a canvas, canvas and brush in hand

“Only known portrait of the artist,” said Portia conspiratorially.

“I expected someone less …” I considered the second part of that sentence as it formed on my tongue, strangled it so I had space instead to say, “I take that back. She looks the correct amount of angry.”

“And why is that?”