0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

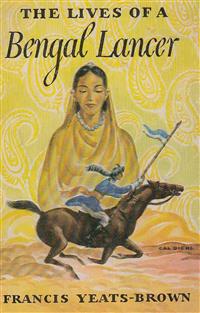

The classic story of an Indian army officer's experience on the North West Frontier of the British Indian Empire and subsequent adventures in World War 1 and Mesopotamia!

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

The Lives of a Bengal Lancer

by Francis Yeats-Brown

First published in 1930

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Bengal Lancer

by

Francis Yeats-Brown

NOTE

Some paragraphs of this book have been taken from contributions to The Spectator and The Field. I am indebted to the Editors of these publications for giving me leave to reprint what I wanted.

F. Y. B.

London, March 15, 1930.

CHAPTER I

NEW YEAR'S EVE, 1905

All the long way from Bareilly to Khushalgar on the Indus (the first stage of my journey to Bannu) I was alone in my railway carriage with two couchant lions.

Brownstone and Daisy were their names. Lord Brownstone, as he was entered in the register of the Indian Kennel Club, was the son of Jeffstone Monarch, and the grandson of Rodney Stone, the most famous bull-dog that ever lived. Brownstone was a light fawn dog, with black muzzle: I had bought him in Calcutta. His wife I had ordered from the Army and Navy Stores in England: she was a brindle bitch by Stormy Hope out of Nobby, with the stud name of Beckenham Kitty, but I called her Daisy. Both Brownstone and I were enchanted by her, for although rather froglike to an uninitiated eye, she fulfilled every canon of her breed's beauty.

When the train stopped, they stopped snoring. If anyone ventured to open the door, Daisy growled in a low, acid voice; and Brownstone became a rampant instead of a couchant lion. So I remained, with leisure to reflect on this great, flat land we were traversing, and on my probationary year in it, just passed.

I was nineteen and a half. A year before I had become the trusty and well-beloved servant of His Majesty King Edward VII. Two months after receiving my commission I had sailed for India.

On the morning of my arrival at Bareilly an obsequious individual had waited on me with a bag of rupees. If I wanted money, he said, he would give me as much as I desired.

I wanted fourteen pounds at once, for an Afghan horse-dealer had brought to my tent door a five-year-old bay country-bred mare—a racy-looking Kathiawari, with black points, who cocked her curved ears engagingly and had the makings of a good light-weight polo-pony. I bought her on the spot.

I had only to shout Quai Hai to summon a slave, only to scrawl my initials on a chit in order to obtain a set of furniture, a felt carpet from Kashmir, brass ornaments from Moradabad, silver for pocket-money, a horse, champagne, cigars, anything I wanted. It was a jolly life, yet among these servants and salaams I had sometimes a sense of isolation, of being a caged white monkey in a Zoo whose patrons were this incredibly numerous beige race.

Riding through the densely packed bazaars of Bareilly City on Judy, my mare, passing village temples, cantering across the magical plains that stretched away to the Himalayas, I shivered at the millions and immensities and secrecies of India. I liked to finish my day at the club, in a world whose limits were known and where people answered my beck. An incandescent lamp coughed its light over shrivelled grass and dusty shrubbery; in its circle of illumination exiled heads were bent over English newspapers, their thoughts far away, but close to mine. Outside, people prayed and plotted and mated and died on a scale unimaginable and uncomfortable. We English were a caste. White overlords or white monkeys—it was all the same. The Brahmins made a circle within which they cooked their food. So did we. We were a caste: pariahs to them, princes in our own estimation.

It was pleasant enough to be a prince. Two dozen valets, and innumerable servants of other kinds had come, with testimonials wrapped up in blue handkerchiefs, to seek employment from me. The eagerness to be my valet had struck me as strange, for I did not then know that Indian servants like a young master, being human in his early years, and worth the trouble of breaking into Indian ways.

So it had come that I engaged Jagwant, a magnificent and faithful person, with elegant whiskers and an hereditary instinct for service. During the fifteen years that he was my friend and servant, I only once saw his equanimity disturbed; and that was not by any worldly circumstance, but the powers of darkness. He was a Kahar, the highest caste of Hindu that will serve Europeans.

Jagwant was with me on board the train, in the servants' compartment adjoining mine. The remainder of my servants—a waiter, a washerman, a water-carrier, and sweeper, and two strong men for Judy (one to groom her and the other to give her grass)—I had paid off with a sense of relief. They had all smelt rather of snuff, and depressed me with their poverty and humility. Indeed, except for a munshi, who came daily to teach me Urdu, and the lordly Jagwant, I could not at this time feel any sympathy with the people of the country that was to be my home. I had expected and imagined much, but not this sad, all-pervasive squalor. Where were the colours and contrasts I had found in books? Where were the Rajahs who ruled in splendour and those other Rajahs who drank potions of powdered pearls and woman's milk? Where the priests and nautch-girls, and idols whose bellies held rubies as big as pigeons' eggs? All I had seen was a tired people, mostly squatting on its heels and crouching over fires of cow-dung.

That, and my British regiment, was the India I knew. In the regiment, I had learned how to drill a company of riflemen, and to see that their boots and bedding and brushes were disposed in the manner approved by the Army Council, and that their hair was properly cut, and that they washed their feet. Also I had learned to hit a backhander under Judy's tail.

I had been rich during this last year (on the chit system) and had enjoyed myself enormously. My last act had been to sell Judy for double the price I had given for her, in order to settle my debts.

Now I was on my way north, to join the 17th Cavalry at Bannu, on the North-West Frontier.

The further we travelled, the larger and livelier the men looked. Women and children remained enigmatic bundles, small and inert.

Those doll-like babies with flies round their eyes—nineteen thousand of them were born every day in India. A staggering thought, all this begetting and birth.... And that girl with the very big brown eyes looking at me as if she was a deer, and I a hunting leopard, what was she thinking about? The bangles that glowed against her sunny skin? Her gods? Food? Why did some girls have a diamond in the left nostril?

Which of these people were Brahmins? Which Muhammedans? Which Animists? There were fourteen million Brahmins in India, I had read in a book, but to me the twice-born and the eaters of offal were alike. Did this slow brown tide that passed my carriage windows fight and make love like the quicker white? Did it possess parts and passions like myself? Perhaps I should find out, as a Bengal Lancer.

At Khushalgar, Jagwant and Brownstone and Daisy and I crossed the Indus and took another train to Kohat; and at Kohat, which we reached in the late afternoon, we packed ourselves into a tonga which already held an officer bound for Bannu, and his luggage.

Every moment of that eighty-mile drive had its thrill for me, but for my veteran companion the journey meant boredom and discomfort. He slept between the stages, waking up only when we changed ponies, in order to swear and drink sloe-gin.

Our ponies, galled at girth and neck, either jibbed backwards to within an inch of a precipice, or reared up like squealing unicorns and dashed downhill for a yard or two, then sat suddenly on their haunches, hoping perhaps that the harness would break and the tonga roll over them and end their wretched lives. Never once would they pull into their traces without some attempt at suicide. When suicide had been averted a rope was reeved under their fetlocks; a groom pulled on the two ends, another pushed the tonga from behind, and the driver applied his whip scientifically to the ponies' ears. Cajoled and goaded, they would jump into their painful collars at last, and gallop on to the next halt.

On the road we passed men like Israelitish patriarchs, and tall, grim women in black, and a gang of Afridis who were dining on thick slices of unleavened bread and pieces of fat mutton. Stout fellows, these. The firelight glinted in their hard eyes.

Once we slackened our pace while a boy ran beside us chattering about a tribal quarrel up the road. To help his cause, our driver agreed to carry twenty rounds of ammunition to the next stage: there we were waylaid by the opposing faction, who begged us to carry a hundred rounds for their party. My companion woke up at this moment and damned them all roundly, but agreed to take twenty rounds, this once, for he explained that we couldn't take sides.

At Lachi we encountered a band of beautiful young men with roses behind their ears. Where in all this waste, I asked myself, did flowers bloom? As far as the forlorn hills of the horizon I could see nothing but rocks and pebbles.

On and on we rattled and crashed, until we came to the sugar-cane crops of the Bannu suburbs, with a mist over them, solemn and mysterious.

My companion loaded his revolver; for there was a Garrison Order that we were always to be armed near cantonments, he told us. A fanatic had recently murdered our Brigade Major.

At the city walls stood a sentry with fixed bayonet. He opened a barbed wire gate for us, and we drove on to the house where my regiment and two battalions of the Frontier Force Infantry messed together. My companion descended here. I reported myself to the Adjutant of the 17th Cavalry and was shown to my quarters.

At dinner that night I sat between the Adjutant and an elderly Infantry Major. The latter breathed fumes of alcohol through his false teeth, like some fabulous dragon.

"Thank God I've finished with the frontier," he lisped. "Thirty years I've had of it. Now they've failed me for command. I'm retiring and be damned to them. There'th nothing but thtones and thniperth here. Up in Miramthhah the other day, a young Political Offither was thtabbed in his thleep by a Mathud recruit—thaid he'd noticed the thahib thlept with hith feet towards Mecca and that he couldn't allow thuch an inthult to hith religion. But they did a thing to the bathtard he didn't like. After he wath hung, they thewed him up in pigthkin tho that the hourith won't look at him in Paradithe. He'll have to anthwer the trumpet of the Archangel wrapped in the thkin of a thwine!"

The port and madeira described constant ellipses over the long mess table, and the elderly Major helped himself at each round.

I questioned the Adjutant about ghazis. He told me that a certain Mullah of the Powindahs was preaching to the tribesmen from the fateful 5th verse of the 9th chapter of the Koran: "And when the sacred months are past, kill those who join other gods with God wherever ye shall find them; and seize them and slay them and lay in wait for them with every kind of ambush." The murder of the Brigade Major had been a bad business. The ghazi hid in some crops at the roadside, waiting for the General, presumably, who was leading a new battalion into cantonments. The General had dropped behind for a moment, so the Brigade Major, who was riding at the head of the troops, received the load of buckshot intended for his chief. It hit him in the kidneys and killed him instantly. The ghazi tried to bolt, but was brought down wounded in the crops by a Sikh sergeant.

"Did they sew him up in pigskin?" I enquired.

"Of course not," said the Adjutant. "That's a yarn. But we ought to do something about these murders. We're having a practice mobilisation the day after to-morrow, and may go out after raiders any day. There's a fair chance of seeing active service here, and decent shooting. Especially the snipe-jheels. The polo isn't up to much, but we mean to go in for the Indian Cavalry next year."

In the ante-room, the evening began to assume a festive mood. We dragged out a piano to the centre of the room. Well-trained servants appeared as if by magic to remove all breakable furniture (especially some tall china jars which had been taken by one of the regiments at the loot of Pekin) replacing it with a special set of chairs and tables made to smash. Senior officers bolted away to play bridge; the rest of us, who were young in years, or heart, began to enjoy ourselves according to ancient custom.

Somebody found an enormous roll of webbing and swaddled up a fat gunner subaltern in it. A lamp fell with a crash. Wrestling matches began. A boy in the Punjaub Frontier Force brought in a little bazaar-pony and made it jump sofas. He had his trousers torn off.

I stood on my head in order to prove that it was possible to absorb liquid in that position. When this seemed tame, I dived over sofas and danced a jig with the elderly Major. Then a dozen of us went off to the billiard-room, where we played fives.

At midnight the fifty of us gathered in the ante-room again and sang "Auld Lang Syne," for it was New Year's Eve.

Hours afterwards, I left the dust and din and walked back under the stars to the bungalow in which I had been allotted a room. I was extraordinarily well pleased with myself and my new surroundings. Everyone in my regiment was the best fellow in the world—and that first impression of mine has not been altered by twenty years of intimacy.

As I sank to sleep, exhausted, I remembered that my feet were pointing westward, in the general direction of the Holy Ka'aba at Mecca, like those of the Political Officer in the Major's story, but I was too tired to move.

The New Year had begun very well indeed.

CHAPTER II

DURBAR AND A DOG FIGHT

Next morning the Adjutant took me to see the Commanding Officer. I was in uniform, belted and sworded and spurred, as I should have been had I been attending Orderly Room in a British regiment. The Colonel wore a brown sweater. His head was bent over a ledger, so that he did not see me salute. The Adjutant coughed. The Colonel looked up, then down to my toes, then up again.

My mind was a blank. He asked me if I was comfortable and I answered that I was extremely comfortable. There was a solemn pause during which all sorts of ridiculous things came into my mind, but I kept silence. Finally the Colonel said: "Well, don't let me detain you."

I withdrew in amazement and hesitated on the verandah, wondering what to do next, for the Adjutant had remained behind. There was a fierce-looking little Indian with a bright red beard sitting on the verandah smoking a cigarette. He looked me up and down, as the Colonel had done; then jumped up and saluted, saying "Salaam, Sahib" in a high-pitched bark, and sat down again. He was in a uniform of sorts, wearing an old khaki jacket with the three stars of a Captain on the shoulder, but his legs were encased in Jodphur breeches and his feet in black slippers. I couldn't make him out at all. He kicked the slippers off, threw away the cigarette, and went into the Colonel's room without knocking.

"Who is the little red-bearded Captain?" I asked the Adjutant, who came out as this curious figure went in.

"That's Rissaldar Hamzullah Khan," he answered. "He's one of your troop commanders. You're posted to 'B' Squadron—all Pathans. As the Squadron Commander is away, Hamzullah will show you the ropes. He's a funny old chap; rose from the ranks. Come along with me now, and I'll introduce you to the other Indian officers."

We walked over to a tumble-down mud-hut, which was the Adjutant's office.

A group of big, bearded men sat there on a bench. They wore voluminous white robes and held walking-sticks between their knees. Another group, without walking-sticks, squatted. The squatters were called to attention by the senior N.C.O. The sitters rose, saluted the Adjutant and looked at me sternly. I was introduced and shook hands with Rissaldar Major Mahomed Amin Khan, Jamadar Hazrat Gul, Rissaldar Sultan Khan, Rissaldar Shams-ud-din and Woordie Major Rukan Din Khan—names that made my head reel. They all said "Salaam, Hazoor" (to which I answered "Salaam, Sahib") except one Indian Officer, who disconcerted me by saying "Janab 'Ali," which I afterwards discovered meant "Exalted Threshold of Serenity," or more literally, "High Doorstep."

In the course of these introductions, Hamzullah arrived. We shook hands. He eyed me narrowly, cackled with laughter and made a remark to the Adjutant in Pushtu—the language of the frontier.

The Adjutant translated:

"He wants to know if you can ride. He says you are the right build. And he says you are a pei-makhe halak—a milk-faced boy."

I felt anything but pleased.

"Hamzullah will take you round the squadron," said the Adjutant. "After stables, there's Durbar."

"If you will excuse me, Hazoor," said this surprising little man, as we walked towards "B" Squadron, "I will inspect the Quarter Guard, since I am Orderly Officer and it is on our way. Then we'll choose your chargers."

"I know exactly what I want as regards my horses, Rissaldar Sahib."

"Good. I will see that you get what you want."

Will you? I thought.

As we approached the guard, the sentry cried "Fall in!" in the queerest squeak. I lingered in the offing, to see how things were done in Indian Cavalry.

Five men and a sergeant sprang up from rope bedsteads and stood to arms. "Carrylanceadvance—visitingrounds" in one mouthful.

Hamzullah threw away his cigarette and stumped round, muttering comments in guttural Pushtu, which sounded like curses—and were.

When the guard was dismissed one of the men turned left instead of right. To my surprise, the sergeant took a stride towards him and struck him in the face. He was a huge yokel with long black hair heavily buttered. His turban fell off and unwound itself in the dust. Not a word was said. The man picked it up and joined his comrades. I stood rooted to the spot, expecting Hamzullah to place the sergeant under arrest.

He grunted and lit a cigarette. Perhaps, I thought, he had not seen.

Years later, when I became Adjutant, I learned what should be visible and what invisible in India sillidar cavalry. But until I had come to understand this, I was continually being surprised and sometimes shocked; therefore a small digression will be necessary if the reader is to see the Bengal Lancers as they were organised in those far-away years before the Great War.

Before the Mutiny, the yeomen and freebooters who served John Company brought their own horse and their own equipment to the regiment in which they elected to serve. They came ready to fight. They fought as long as there was loot to be had, and then returned to tend their crops.

Later, owing to the difficulty of maintaining a standard in equipment and horseflesh, it was found more convenient for the recruit to bring a sum in cash instead of a horse and saddle, but the principle remained the same, namely that the apprentice brought the tools of his trade.

In my day the cost of a sillidar cavalryman's complete equipment was about £55. If the recruit could not bring the whole amount, he brought at least £10, and owed the balance to the regiment, repaying the loan month by month out of his pay.

Each sillidar regiment (there were thirty, I think) maintained a Chanda, or Loan Fund, out of which these advances were made. As the administrator of this fund, the Commandant of an Indian Cavalry Regiment was to all intents and purposes the Managing Director of a company in which each man held from £10 to £55 of debenture stock, the debentures being secured on horses and equipment. The Colonel might also be considered as a contractor, who had engaged himself to supply the Indian Government with 625 cavalry-men, fed, mounted, provisioned, equipped (except for rifles and ammunition which were supplied by Government) at the cost of £2 per month per man, including all the transport and followers of the regiment—some 350 servants, 300 mules and nine camels.

The pay of the men was about 30 rupees a month—say £2—rising by small increases to £20 a month for the highest Indian rank, that of Rissaldar Major. At a very small cost, therefore, India was served by a body of yeomen complete with horses, tents, servants, mules, camels—an admirable bargain for Government, and a good one for its servants, for the sillidar cavalrymen was at once freer and more responsible than any other soldier in the Empire. He was freer, because men serving for the pittance they received after repayment of their loans had to be treated like the gentlemen adventurers that they were; and more responsible because if a horse died or any loss to property occurred through negligence, the owner had to pay for it.

The regiment looked on itself as a family business. We bred horses as well as bought them. We all took an interest in our gear. The Colonel would no more have ordered a fresh consignment of saddlery without discussing the matter with his Indian Officers than a manager would install a new plant in his factory without consulting his directors. All this made for friendliness, and broad views. We had not time to make our men into machines. They remained yeomen who had enlisted for izzat—the untranslatable prestige of India.

That such a state of affairs should be abhorent to the mind of the War Office is readily understandable. The sillidar cavalry was abolished immediately after the Great War on the plea that its mobilisation was complicated and unsatisfactory under such individualistic arrangements. So now our families are broken and scattered, and only a few ancestral voices, such as mine, remain to prophesy the woe that must attend their passing. But India rarely changes, and rarely forgets. When we give up trying to teach our grandmother to suck the eggs of Western militarism, she will again raise her levies in the way that suits her best.

To return to "B" Squadron. The Colonel came towards us, attended by the numerous staff that follows in the wake of every oriental autocrat. My Squadron Commander was away. What should I do?

Hamzullah's foxy eyes perceived my embarrassment. He whispered: "Blow your whistle, Sahib."

"I haven't got one."

"I'll blow mine."

The great man was upon us: Hamzullah blew a piercing blast.

"Go on with your work," said the Colonel, carrying a silver-headed malacca cane towards his helmet in answer to our salute. He wore civilian clothes.

What now? I turned again to Hamzullah, who barked, "Hathe de lande" which is Pushtu for "Hands underneath."

The men, who had been standing at attention with elbows squared in front of their surprised horses, now resumed their brushing of bellies. The squadron kicked and squealed.

Stopping in front of a chestnut mare, the Colonel pointed at her fetlocks, which were hairy. Her owner dropped his brush, and rubbed them furiously, and the mare let fly with both heels, kicking over a bucket of dirty water.

"These devils never do what they're told," growled the Colonel. "Legs should have been done by now. Ask Hamzullah to tell you the Order of Grooming after I've gone. He won't see that it's carried out, but he'll tell you."

The procession continued, the Colonel leading, a dozen of us behind, hanging on his words.

"Tail wants pulling," he said to Hamzullah.

"Hazoor," said Hamzullah.

"A dirty horse is never fat."

"Hazoor," said Hamzullah.

"Staring coat. You must get rid of that boy if he can't keep his horse better. Fat enough before, under Khushal Khan."

"I shall warn him, Hazoor. He's a zenana-fed brat!"

"File his teeth," said the Colonel.

I started, but saw he was alluding to a raw-hipped waler.

"If that brute doesn't get fatter, put him down for casting."

"Yes, sir," said the Adjutant.

"When did I buy that mare?"

The Woordie Major produced an immense book, carried behind him by an orderly, and opened it at the proper place.

"Lyallpur Fair, 1903," mused the Colonel. "She's turning out well. I think we'll get a foal out of her. Send her to the Farm."

"Very good, sir," said the Adjutant, making a note of her number.

"And, by the way, give this young gentleman a copy of Standing Orders and Farm Orders."

"Another tail wants pulling," said the Colonel. "Do you know how to pull tails, Yeats-Brown?"

"Yes, sir."

"You had better get Hamzullah to show you how we do it here. Are the men for Persia chosen?"

"The——?"

"Yes, Hazoor. I have chosen them," says Hamzullah.

"Bring them at Durbar with their horses. A great many tails want pulling."

When the Colonel came to the end of "B" Squadron I drew breath again. A blessed calm descended on us. Over in "C" Squadron the whistle sounded, and then the cry of "Malish." Here we no longer bothered about grooming. The men stroked and patted their horses' backs, or leant against them for support. The East had returned to its old ways.

"Tell me, Rissaldar Sahib, about the Order of Grooming."

"Hazoor, it is in a book," answered Hamzullah in his high-pitched voice. "Five minutes for the horses' backs, ten for their blessed bellies, five for their foolish faces, and five for their dirty docks. A time to brush, and a time to rub, and a time to put everything in its place. That is good. But I am an old man, and cannot remember new ways. If I see a dirty horse in my troop, I beat its owner. If it is again dirty, I whip him with my tongue. And if that has no effect, he goes. Look at the result."

The result was that a hundred satiny coats shone in the sun.

"But some of the tails want pulling," I said.

"I have known the Colonel Sahib for thirty years," said Hamzullah, "and never yet have the tails of any troop been right. Not since we enlisted the first men and bought the first horses."

"Were you here when the regiment was raised?"

"Yes, Hazoor. I was a syce then, for I was too small and ugly to be a soldier. The Colonel Sahib was Adjutant. After five years he enlisted me as a fighting man. Before I die I shall be Rissaldar Major."

My heart warmed to him.

"I have much to learn, Rissaldar Sahib," I said. "I hope you will teach me."

"Men and horses are simple," he answered, "but mules are spawn of Satan. We can't get the syces for them nowadays. Wages are ridiculous. The young men all want to go to school. What do they learn there? Softness! Huh!"

We continued to stroll round the squadron, taking not the slightest notice of the men, some of whom were at work, while others kept dodging into their huts, where cooking was in progress. At last a trumpet call announced "Water and Feed," and after that "Durbar."

All India loves Durbars. They are her Parliaments, based on her ancient village system of a headman advised by a panchayet—five elders—and she may again rule herself by them.

An armchair is set for the Colonel, with a low table before it. By his side are stools for the Adjutant, Second-in-Command, the Rissaldar Major (senior Indian officer) and Woordie Major (Indian Adjutant). At right-angles to these high personages are two benches, on which the remaining British and Indian Officers sit in any order, intermingled. At the fourth side of the square, opposite the Commandant's table, are marshalled the persons to come before him.

All round, but particularly facing the Commandant, the men of the regiment are sitting or standing; spectators to our way of thinking, but something more in their own estimation, for they are there to see that justice is done. That they do not execute it themselves is immaterial; Durbar is a testing time for the Commandant. If he has not the wit and personality to rule, his deficiencies are soon apparent.

The Indian Officers rise, in turn, to present their recruits.

"A" and "B" Squadrons are bird-faced, white-skinned, keen-eyed boys, wild as hawks. They come from Independent Territory, and have called no man master. The Colonel looks them up and down, as he did me, and asks their parentage. Whether he accepts or rejects a candidate, his cold politeness remains unchanged: "He needn't wait," he says, or "Send him to the doctor," or "I don't think we've room," or "As he's a relation of yours, we'll give him a trial."

"C" and "D" Squadron recruits are Punjaub Muhammedans, slow and strong as the oxen they drive at the plough. They are darker than the Pathans, and have the manners of shrewd peasants, self-confident and a little suspicious. Then come the men for Persia (medalled veterans going to Teheran to serve as the Legation Guard) and the leave men. No soldiers in the world have so many holidays as Bengal Lancers. An Afridi wants to settle a blood feud. His uncle has been shot while gathering crops among his womenfolk. He must go at once to attend to the affair, or his face will be blackened in the village.

Then the defaulters. One of my men has allowed his horse to become rope-galled. A small offence apparently, but Hamzullah does not bring men before the Colonel unless he wants them severely dealt with.

"Fined fifteen rupees. You'll go, if you give us any more trouble," says the Colonel.

"Hazoor, I have a wife and three small children to support."

And indeed twenty shillings fine, to my thinking, comes heavy on a man whose pay is about five shillings a month after deductions.

"Your children are cared for by your brother," says the Colonel (who knows everything). "Get you gone."

Finally we come to the animals, who number a thousand and whose affairs are complex. Should the horses be fed on gram and barley, or gram alone? Should we buy ten truckloads of oats, or only one? Do the mules require an extra blanket on these winter nights? Engrossing questions these, and the Rissaldar Major and Hamzullah Khan and the Adjutant have much to say concerning them, for there is a nice distinction between discipline and administration in Durbar. Justice is a matter for one mind, economy for many.

Meanwhile, the junior British officer present at these proceedings sits twiddling his thumbs with boredom. He does not know that before the British came every ruler in India transacted business thus coram publico, and that to-day's meeting under the banyan tree is a continuance of that tradition. He does not know (or care) if our civil administration is becoming intolerably dull, and our justice dilatory. He does not know that Indians are becoming puzzled by our methods, and that the races of the North have buried a hundred thousand lethal weapons under their hearths in a determination never to be ruled by babus, brown or white.

Quotations from the Koran are being advanced in support of—what? The fit of a lance bucket? The quality of a picketing rope? Or is it something to do with the pay of syces?

Brownstone and Daisy have trotted up to see what their master is doing. They have no business here, but Brownstone, bolder than his mate, wriggles up to me, looking round the corner of his body and arching his back. He wants to be slapped on the loins. No Brownstone, this is a Durbar.

Daisy, looking very batrachian, is gazing up at me from a safe distance, her wizened muzzle cocked enquiringly. A chow, a terrier, and a friendly mongrel have also arrived, encouraged by some of the younger officers, who know that a dog fight has its uses.

"Take those brutes away," says the Colonel.

It is too late.