Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Muswell Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

A terrific, atmospheric thriller. Taut, compelling, masterfully constructed. Outstanding. William Boyd. I went to Greece to embrace the binary code, to get off the sidelines and become a player. To live in the moment. Or, as Ellie put it, to become my own man. Was I accountable for the horror, that fateful summer? Looking back, it's easy enough to pinpoint the sliding-door moments where I went wrong. But then, what use is hindsight? As Kierkegaard wrote: 'Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards'. Cold comfort when you've taken another man's life.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 401

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

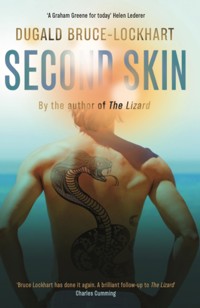

THE LIZARD

Dugald Bruce-Lockhart

v

For Mouse and Frog

vi

vii

You’ve got a devil inside you, as well, but you don’t know his name yet, and since you don’t know that, you can’t breathe. Baptise him, boss, and you’ll feel better!

nikos kazantzakis, Zorba the Greekviii

Contents

Prologue

According to Ellie I was too eager to please. Unable to make a decision; not my own man.

Which is why she dumped me.

Why I left for the Greek islands in the summer of ’88.

And ended up in jail for murder.

How far back the seed was sown is impossible to tell. Nothing comes from nothing. Be it fate or free will, life boils down to continuous binary code: a never-ending series of choices; yes or no; in or out; fight or flight. Until death ends the equation. Humans overcomplicate it; we invent shades of grey, hover in a limbo of moderation and deem it intelligence. Only the mad and the brave change the world. The rest look on in wonder.

I went to Greece to embrace the binary code, to get off the sidelines and become a player. To live in the moment. Or, as Ellie put it, to become my own man.

Was I accountable for the horror, that fateful summer?

Looking back, it’s easy enough to pinpoint the sliding-door 2moments where I went wrong. But then, what use is hindsight? As Kierkegaard wrote: ‘Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.’

Cold comfort when you’ve taken another man’s life.

I

4

1

I stepped off the Athens airport-transfer bus at the port of Piraeus on the morning of 27 May as the sky turned pink. The combination of heat, diesel fumes and the swelling army of backpackers was compounded by coiled street lamps that bathed the environs in a weird orange murk, through which squat ferries along the harbour concourse loomed like giant slugs. In the shadows lay a scattering of ghostly kiosks selling pretzels, water bottles and bread rolls, where island-hoppers assembled in droves to stock up on supplies; a hungry, apocalyptic exodus.

A far cry from the Greece I’d seen in magazines.

Trawling the ring of travel offices with their overenthusiastic ticket touts, I found what appeared to be the best deal for a one-way journey to Paros, took a seat at a café along the harbour wall and, ordering an iced coffee to ease the headache that had grown steadily since my 4 a.m. arrival, settled in for the wait as the port lumbered to life.

As we drew nearer to departure, the café filled up, and it wasn’t long before a fellow traveller sporting a tie-dye 6neck scarf came over to share my table. He gave me a nod and pulled out a sun-bleached copy of Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist. Then, with an artful flick of his Zippo lighter, he lit one of his Camel cigarettes and ordered a Heineken. I checked my watch – not even 8 a.m.

Exactly the sort of man Ellie would go for. Independent to the hilt. A cool contender, suave and assured, with a natural breeziness I could only dream of.

Sucking the sugar granules from the bottom of my glass, I focused on the seagulls dive-bombing the pretzel kiosks, assuring myself that I needn’t feel intimidated. Yes, I was a little on the conventional side, and certainly not someone who looked natural holding a cigarette, but who cared? I’d just arrived. In a matter of days I’d fit in with the best of them.

At which point, an official voice cut through the hubbub of the café, barking departure instructions.

The Apollonia was ready to board.

We left Piraeus bang on nine o’clock, contrary to all the warnings I’d been given on Greek efficiency. Standing on the top deck with my fellow bleary-eyed passengers, I watched Athens retreat into the heat haze; the sea was so calm it was hard to distinguish which was actually moving, the ship or the land. We simply seemed to separate.

As the steel deck throbbed with increasing urgency beneath my feet, mainland Greece disappeared from the horizon and we passed the first cluster of islands, apparently uninhabited. Pressing on past these scrubby, rocky outposts into deeper water, the ship soon picked up the open swell and started its gentle roll. As the sun climbed higher, I eased off my shirt, exposed my pallid flesh to the salt air and embraced my new-found anonymity.7

St Andrews University and its trickle of tea shops, golf courses and cobbled streets seemed a universe away. Good riddance, too. Alistair Haston, student of moral philosophy and German – no more. I was starting over, shaking things up. A blank canvas upon which to draw new lines. Cleaner, stronger lines. I’d have to return to uni after the summer break to complete my fourth and final year, of course – I was hardly going to chuck in three years of study – but for now, it was goodbye to books and intellectual enlightenment. Logic had been my undoing. Ellie wanted a ‘doer’, not a thinker. I was after the innate wisdom of my primaeval forefathers, where the only qualification needed was an ability to hunt and fight: a stripped-back, honest existence. The hunter-gatherer society. Hunt down the supper and fight the neighbour off your turf – or your woman. Sod the degree. Air. Food. Water. Sleep.

I could hear Ellie’s snort of derision. I couldn’t be further removed from my ancestral alpha males than I already was. People-pleaser extraordinaire.

Stepping back from the railing – I could feel the beginnings of sunburn on the tops of my shoulders – I slipped the shirt back on and, cursing my lack of foresight for not having packed any painkillers, made my way through the throng of semi-naked bodies down to the covered deck below in search of something to ease the now pounding headache. The iced coffee seemed only to have had the reverse effect; I needed something stronger, chemical.

The lower deck was populated by Greeks primarily, in their forties plus. Some were grouped around tables, smoking and playing backgammon and cards, others slept curled up in the banks of shiny plastic armchairs. I spotted a couple of octogenarian women dressed in the traditional all black. 8Faces lined like cracked mud, silver crucifixes around their necks. One of them eyed me with vague disinterest, the way a tortoise might eye a dock leaf. I smiled but it wasn’t returned.

I averted my eyes, turned towards the bar to see what was on offer and scoured the shelves in search of pharmaceuticals. Unable to spot anything promising among the fake coral necklaces, batteries and ‘Sea Captain’ hats, I cast an eye over the selection of beers as a possible alternative and noticed a faded poster on the wall: Michael Jenner. Eighteen years old. Missing since July 1986, last seen on Mykonos. Anyone with information should contact the police or the British Embassy.

Two years ago. They were still holding out hope – unless it was an oversight and the poster had been left to rot on the walls. Striking fellow. Unruly red hair and emerald eyes. There was something familiar about his expression: his eyes were alive and lit up – a pull at the side of the lips that suggested something was happening just off-camera, a shared secret.

I remembered that feeling sitting on a train with Ellie and a group of second-year students returning from the summer holidays. They’d been celebrating and lamenting, in turn, the follies of holiday romances. Ellie had reached under the table and squeezed my hand – a silent complicity that we were one, invincible, above such frippery. I wore the tiniest of smiles. Certain. Complete. A feeling that all I needed was right next to me.

Yeah, right.

Six weeks before, meeting up in the rain after her twelve o’clock anthropology tutorial, Ellie and I hadstood, hand in hand, under the cloisters of St Salvator’s Quad, waiting for a lull in the deluge before making a run for it. She’d been asking me all term if I’d come out to Greece and visit her 9relations in Athens – her paternal uncle was an influential shipping magnate who controlled half the tankers in the Med, and she assured me her cousins would show us a good time. A self-professed yachtswoman, she boasted she’d commandeer her uncle’s luxury catamaran, knock the landlubber out of me and give me sea legs. Not wanting to lose out on other options, however, I’d dithered for two months, unable to commit. Finally, realising all too late that friends and family had all made arrangements elsewhere, I decided to take the plunge, or risk facing the summer months alone. So I wrapped my fingers around Ellie’s, took a deep breath and told her that I’d love to join her and her Greek cousins for the summer break, thank you.

She turned to me, eyes moistening, tucked a lock of wet hair behind her ear and told me that something just wasn’t right; shecouldn’t quite put her finger on it. Although, when I told her to stop the tears, the finger found it easily enough: ‘We’re wasting each other’s time – you don’t know who you are, or what you want. You rely on me and it’s weighing me down. I can’t carry both of us.’

With that, she stepped out across the sodden grass in a melee of auburn hair, lever arch files and denim, and left me there, confused and admonished.

I tried desperately to reopen negotiations, but her gatekeepers were well prepped and my advances rebuffed at every turn. As for my friends, they were useless. They simply nodded along, bought me another pint of cider and black, and returned to the slot machines: Taking it a little seriously, poor bugger. So I sought guidance from my moral philosophy tutor, collapsing onto his tobacco-stained chaise longue in floods of tears, claiming that life, studies, and the whole notion of a career was meaningless if one was ‘out of love’. How could 10I begin to think clearly, see straight, eat, sleep or breathe even, in such a state – let alone finish my degree? Ellie was my life, my reason to get up in the morning. ‘Without Ellie,’ I concluded, ‘I might as well be dead.’ But all he did was pour me a brandy, suggest I was critically co-dependent, and recommended I see a shrink.

After five days pining away in my bedsit, disgusted by my innate fickleness, I set off through the quad, past the New Picture House with its poster of Tom Cruise and Kelly McGillis straddling a large motorbike, and made my way to the travel office in the students’ union, where, approaching a stringy sales assistant in a ‘The Cure’ T-shirt, I announced I wanted to do the Greek islands. Without Ellie. Alone. Teach myself to sail – that’ll show her. Fine, I’d use up a term’s living allowance in one swift stroke of the pen, but if I put my nose to the grindstone, I’d claw back some of the deficit. And anyway, weren’t all students in debt?

Morag, the travel agent, couldn’t agree more, and issued me with a one-way ticket to Athens.

Back at my halls of residence, having picked up £20-worth of drachmas and £50 in travellers’ cheques from the bank on North Street, I immediately set to packing a rucksack – just the essentials: no camera, nothing to read, not even a notebook. And as a grace note, buoyed up by my proactive decision-making, and in the vain hope I might provoke a reaction, I wrote a disingenuously cheerful letter to Ellie, telling her not only of my plans to head, solo, to the Greek islands, but also claiming that I was ready to be just friends, despite my profound belief we were made for each other. She never replied.

Six eternal weeks …

11A shout from across the cabin cut through my melancholia. Leaving Michael Jenner to his secret smile, I swung around to witness the flustered arrival of the barman, chequered apron flapping from his waist, barking at no one in particular. Leaning across the bar towards him, I was ordering an Amstel beer, when a voice piped up behind me. ‘Mythos every time, mate.’

I turned and came face to face with a grinning Australian. He was in his late twenties, complete with a wide-brimmed leather hat and mahogany tan. ‘The Amstel’s piss and they water it down anyway.’ He wiped his hand on his T-shirt, took off the hat and ran a hand through his matted blond hair. ‘Stay local.’

Continuing to grin, he lit a cigarette.

‘On your own?’

He lifted his chin and blew the smoke straight up in the air without taking his gaze off me. For a moment, I couldn’t answer; I was struck by his extraordinarily translucent eyes. The colour was wrong – it didn’t quite fit with the rest of his face.

‘Pretty much,’ I replied finally, unnerved by the directness of his stare. ‘Heading to Paros. Second stop, I think it is.’

‘Looking for work?’

‘Actually, I am.’

‘Paros? There are way more bars and clubs on Ios.’

‘Didn’t fancy the “Ios Cough”,’ I replied, remembering Morag the travel agent’s advice to stay away from Ios – every year, countless tourists died from alcohol poisoning, to the point where the authorities would turn away the inbound ferries for days at a time in a bid to restore order. A hellhole party island to be avoided at all costs.

‘Fair play,’ he said, holding my gaze. ‘Still, depends where you go.’12

There was, in fact, a more telling reason: Ellie’s cousin owned a restaurant on Paros, near the port of Naoussa on the north of the island – the Tamarisk. Ellie had earmarked it for our itinerary. Somewhat pathetically, I was entertaining the hope she might stick with her summer plans, head to Paros with her cousin and visit the family restaurant … where, fancy that, I’d run into her.

But the Australian didn’t need to hear that.

He blew out another long stream of smoke. ‘I’ve got a few contacts over here. You wanna job, I can hook you up, no sweat.’

‘Thanks,’ I replied, still thinking of Ellie.

It was, of course, stupidly unlikely. And in any case, what was I going to do – stake out the restaurant and wait for her to show up? I had a tiny budget; I had to work. Besides, if Ellie knew I’d been lying in wait, she’d run a mile. The idea was to play the aloof game, the independent game – not become a stalker.

‘No worries,’ said the Australian. ‘What’s your thing – what do you do?’

‘Probably going to do some labouring first,’ I replied, looking around for the barman, who had once again disappeared. ‘Build up a resistance to the heat and stuff. Might get down to Ios later in the summer.’

Unless I did hook up with Ellie – convinced her she’d made a terrible mistake …

Wake up, Haston.

‘Right,’ he said, flicking his ash on the floor. ‘Like working on a building site isn’t gonna fry your skin to shit.’

‘True.’

Still, faced with ten or so islands to choose from, the possibility of bumping into Ellie had at least helped make my 13decision: Paros was as good as any. And according to Morag, there was plenty of work, it had more to offer than the other party islands, and boasted some of the best beaches in the Cyclades.

‘I’ll take whatever comes my way,’ I concluded, noticing the tattoo on his neck, just behind his right ear – a lizard. Dark green.

‘Right on.’ He clapped me on the shoulder. ‘What’s ya name, mate?’

‘Haston,’ I replied, flinching at the physical contact.

‘Like the car?’

‘With an aitch.’

‘I’m Ricky. Wanna play a game of quarters?’

Before I could admit I didn’t know what that meant, he put an arm around me and said: ‘Come with me, I’m going to introduce you to some friends.’

On the sun deck, Ricky brought me before his ‘crew’: there was Matt, a six-foot-four Aussie Rules football player who looked like John Lennon; Diane, a Kiwi who taught maths at a secondary school in Wellington, and who, whenever she spoke, sounded like she had a chunk of phlegm stuck in her throat; and finally Parrish, a slow-drawling Texan who was studying medicine at Chapel Hill in North Carolina.

They were all stoned.

Nonetheless, they welcomed me like I was a long-lost friend, and didn’t seem to notice or care that I was a straight-laced, conservative ex-public schoolboy whose only experience of drug taking was limited to soluble aspirin.

Along with the first few cans of beer came a barrage of personal questions, which I at first deflected but found increasingly palatable with the aid of alcohol. Soon enough I felt like 14a celebrity. I’d never imagined that studying philosophy and German would ever sound cool. And when I mentioned my break-up with Ellie, the group edged in tighter – drunken solidarity for the plight of the English bloke with a broken heart. Diane pushed Matt out of the way, squeezed in next to me and laid her soft legs across mine. She kissed my neck, put a slender arm around me and said she’d cure my woes – ‘Bushman style’, whatever that meant.

‘We’re gonna get you shit-faced,’ declared Parrish, cutting to the chase. ‘Fucking blotto.’

A cheer rolled across the deck.

‘Welcome to the club, ya Pommie bastard!’ yelled Ricky, spraying his can of beer over my face. ‘The club’s about spreading the word, and the word is love.’ With that he planted his face on Diane’s lips and the two of them rolled onto my lap, as, out of nowhere, a chant struck up for ‘quarters’.

I joined in, the infection of goodwill spreading like sun cream. Matt whipped off his shirt and ordered us to follow suit – house rules. We obeyed, including Diane, who revealed she was wearing a silver-spangled bra. The bra lasted a matter of seconds before she unclipped herself and threw it at a pair of lanky Swedish girls who were spectating from the railings behind their sunglasses and straw hats. She then drew a circle around each puffy nipple with a tube of green sunblock and made me complete the left breast, ‘to help me get over my girlfriend’, while everyone vied at once to explain the rules of the game.

From the tumult of drunken shouts, I managed to glean the essentials: the idea was to bounce a ‘quarter’ – an American quarter-dollar coin, which Parrish duly provided – into a glass that contained a shot of Jack Daniels. If I made it, I’d get to choose who drank it and would be allowed another 15turn. If I missed, I’d have to down the glass and refill it for the next person to have their turn. The game ended when someone puked or passed out.

‘Fuckin’ simple, mate,’ said Matt, clapping me on the back. ‘Didn’t ya girlfriend teach you this one?’

I laughed and admitted she had failed in that respect. Diane gave Matt a slap and told him to have ‘some fuckin’ respect’ – and then kissed him. She then kissed me.

Ricky kissed Parrish.

Parrish tried to kiss me.

I gave him a nifty slap, which drew a cheer, followed by another wave of onlookers keen to witness the antics.

Preliminaries out of the way, the game got underway as George Michael’s ‘Faith’ riffed from the ghetto blaster. And as the new member of the club, I had the honour of starting. I held the coin between finger and thumb, took aim and bounced the thing sharply off the table, plonk, straight into the shot glass.

I was astounded.

‘The guy’s a fuckin’ natural!’ screamed Matt, slapping me across the back.

‘Rookie’s luck,’ came the riposte from Ricky as he scratched his tattoo. ‘Won’t cop that shit again.’

I slotted another. And then two more.

Competitive by nature and with an unhealthy taste for praise, I was hooked. I picked on Ricky and made him drink each round; I was in awe of him and wanted to make an impression, as well as punish him for his earlier jibe. After my third successful toss, I invented a victory dance: a four-limbed robotic crabbing motion that had them in stitches. The others took it on too. Every time someone scored, out came the dance. The dance drew cheers from the club, which in turn 16drew an increasingly larger crowd of spectators. Before long, over half of the top deck were doing it.

I was high as a kite on sheer camaraderie, something I’d not felt since my dismissal by Ellie. The conviviality grew, the noise increased, and time slid by in a wash of pickled sunlight.

Then it all went wrong.

A series of extra forfeits were put into force, at which point the club ganged up on me. In one fateful round, I slugged three shots from Matt and Diane, followed by a quintuple: for swearing twice; for pointing at Ricky with my finger rather than my elbow; followed by putting the empty glass back on the table without the Jack Daniels in it – which I forgot to call ‘liquid’.

Things turned hazy.

I remember the ghetto-blaster on full whack – ‘It’s the End of the World as We Know It’ by R.E.M.; Parrish and Matt were dancing naked with two Russian girls, braids in their hair, rings and hoops in every nook and cranny of their faces; a steward showed up, told them to put their clothes back on or face arrest; I remember the crowd jeering him back to his lair; I remember wanting to get out of the sun; I remember Ricky breaking out his video camera, filming Diane and me doing shots; I remember him encouraging her to kiss me; I remember her kissing me – the camera lens in my face.

After that …

Nothing.

When I came to my senses I was no longer on the boat.

I was lying on the ground at the foot of a dry-stone wall opposite a café; no shirt on my back, my chinos soaked in piss, and my hand resting in a puddle of golden puke.17

I checked the contents of my rucksack and took stock.

On the plus side, I was on dry land, I had all my clothes – minus a T-shirt – and was still in possession of my wallet. But my passport and travellers’ cheques were gone.

I had 1300 drachmas in change.

Seven quid.

Wiping the vomit from my fingers, I closed my ears to the increasing shouts of disdain emanating from the restaurant and staggered back and forth across the harbour square to see if my passport and cheques had fallen out nearby. I tried all the cafés in the immediate vicinity and asked at the tourist information centre by the windmill. I tried the ferry kiosk and the two travel agencies.

No joy.

Stumbling across the dusty tarmac, blinded by the brightness of everything around me, I headed towards the town end of a heavily populated sandy beach and took advantage of a shop bristling with floatation devices to pick up a bottle of water. Ducking out of the sun, I knocked over a postcard stand and inadvertently discovered where I was – Paros.

That was something, at least.

I paid eighty drachmas for the water, made a wavering beeline to the beach, and wading through the piping-hot sand to the only shade unclaimed by any beachgoers, I tossed the rucksack to the ground, flopped back against the trunk of the thickest tree and without pause emptied my litre bottle of water. Without ID there was no doing anything, let alone the fact I’d need a passport to claim back the lost travellers’ cheques. But then, if I told the police, they’d ship me straight back to Athens and the British Embassy; from there, the authorities would put me on the next available flight to the UK. Game over.18

No way could I go back now.

What would Ellie say?

For the next six hours, I sheltered from the scorching heat under the boughs of my olive tree, debating whether I should take a bus up to Naoussa in the north and try and track down Ellie’s cousin – although, were I to find her, it wasn’t clear how she could help, apart from lend me money. Give me a job? Why would she feel the need to do that? I didn’t even know her name; I was to all intents and purposes a stranger. Would Ellie have mentioned me? Possibly. But then she might also have told her we were no longer together. Besides, the fact that Ellie’s cousin owned the restaurant didn’t mean she would necessarily be in residence. Furthermore, Ellie had planned to take me to her uncle’s house in Athens before travelling the islands, and even then, the plan had been to go sometime mid-June. Two weeks away at the earliest.

I remained stewing in my hangover, kicking myself for not having done the groundwork on finding out exactly when – or indeed, if at all – Ellie was planning on her Greek excursion, until, at dusk, I pulled myself together, reminded myself I was there to reclaim my independence and not wallow in heartbreak, then ventured north along the bay to take advantage of the thinning crowd and have my first swim.

Standing waist-deep in the silky water, I started a conversation with a fellow bather, Roland, a traveller from Glasgow who had zero tan, a shock of ginger hair and was wiry as a whippet. He was working on a building site on the other side of the island and had arrived a month ago with the first wave of workers for the season. As he hoisted first one leg then the other out of the water to wash the flakes of paint from his pasty, freckled legs, I told him of my predicament.19

‘Aye, gotta watch yer back around here,’ he said finally, ringing the water out of his ear with his little finger. ‘Passports sell for a thousand quid on the black market.’

He then gave me the low-down on working on the islands.

Casual work was managed by locals, who paid around 2,500 drachmas for a day’s graft – eleven quid. No food or water included, you had to get that yourself. Because I spoke another language, I’d get work kamakying – chatting up passing tourists in an attempt to lure them to lunch or dinner. There was no pay, but if you were good at it you could make decent tips, and you were always fed.

‘And there’s the usual stuff,’ he continued, rubbing the paint from his scalp. ‘Washing dishes, selling watermelons on the beach, bartending – that kind of thing.’

‘Any chance of you putting in a word to your boss?’

I was staring an opportunity in the face.

He blinked at me with a crooked smile. ‘Ever worked on a building site before?’

‘Sure,’ I lied. ‘I mean, I can’t do any of that plastering stuff, but I can paint, strip walls, that kind of thing.’ I was fit and willing – that had to count.

‘I’ll ask my boss in the morning,’ he chuckled, picking yet more paint out of his hair. ‘He’ll say “yes”, but don’t get your hopes up, it’ll be dogsbody stuff at the hands of one his lackeys.’

My spirits rose immediately. Manual labour, working my passage for an honest crust of bread – exactly what I needed. It would impress Ellie no end.

‘Yeah, if you’re happy with any old shite, I’m sure there’ll be something for you.’

He told me to find him at the Koula campsite café in the morning at six-thirty, and we’d take it from there. I thanked 20him, to which he gave a cheery ‘nae fuckin’ bother’, then loped off across the beach into the twilight.

I flopped back into the brine, congratulated myself on seizing the moment and watched the silhouette of Paros Mountain sharpen against a bruised sky.

Welcome to Greece.

It was all looking good.

As I swam further out to avoid the jutting rocks below my feet, a guttural shout brought my attention back to the beach: Roland was standing at the campsite gates, his pale figure visible against the dark mantel of the cypresses: towel round his neck, rinsing his feet under the freshwater tap, hand raised mid-salute. ‘Watch out for a fat, lazy cunt called Leo,’ he yelled, his voice echoing off the cliffs across the bay. ‘He’ll eat yer lunch if you turn your back on the bastard.’

2

An apricot dawn brought a lightness of spirit, and a not-unsuccessful night’s sleep under the mosquito-infested cedars along the beach wall renewed a belief in my hunter-gatherer potential.

Cajoled off my patch by an overfriendly stray dog, I walked north along the bay, stashed my kit in a clump of bamboo behind an old goat hut, then returned to the campsite to find Roland. He was already up and waiting for me, and proving true to his word, took me on the back of his moped to the building site depot where he introduced me to his boss, Kyros, a massive man in a string vest and tight shorts who, despite being so hairy he looked like an ape caught in a hammock, was charm itself: Yes, of course there was work for me, when could I start? Now? Perfect.

In seconds, it was all tied up. Roland set off for the resort of Piso Livadi on the east coast to continue work on a bijou new-wave hotel perched above the strand, and Kyros introduced me to his nephew, Leo, an equally massive man who had a mane of hair down to his shoulders and wide, hairy 22nostrils. All lion, for sure. He couldn’t speak any English, but via a series of hand gestures we got off on the right foot.

What was Roland worried about?

Two weeks passed.

The spring flowers sloughed off their adornments under an increasingly sweltering sun as I acclimatised myself to the rhythm of the island, cutting my teeth on a near hand-to-mouth existence. By night, I slept on the roof of the goat hut, high enough off the ground to keep the mosquitoes at bay and remote enough for the police not to bother me; by day I was at work, refilling the coffers. It was hard graft, at times monotonous, but it felt honest. Each morning at the depot we stacked scaffolding and timber onto our flatbed truck and, with Leo at the wheel, delivered the materials to the smattering of building sites dotted about the island. Afternoons, we painted rooftops. We never really spoke, but it didn’t matter; I felt privileged to be simply sharing space with a bona fide local. At the end of each day when Leo dropped me back in Parikia, I almost missed his company.

I didn’t go out at night. Without secure funds, I figured I’d build up some savings before allowing myself such frivolities. I spent some of my downtime writing in my makeshift journal – a half-used school exercise book I’d found discarded in the dried thistles by the roadside near the campsite – but I mostly snorkelled off the cliffs at Krios, touched by the cold, swollen fingers of the open ocean, the misty sea floor carpeted in thousands of black urchins.

I thought of Ellie less and less. My philosophy tutor would have labelled it ‘denial’: pushing all memories of her into a dark recess of my mind, stored out of harm’s way, yet 23accessible in a crisis. But my tutor was history. I felt stronger – did I dare say it? My own man.

In fact, so certain was I of my metamorphosis, I decided a celebration was in order, and on the Thursday of my third week on the island, after Leo and I clocked off early from work, I broke protocol, dipped into my meagre savings and hired a moped to check out Naoussa, in the north of the island.

Time to pay a visit to the Tamarisk.

Naoussa, with its wind-beaten, untarnished rocky coastline, was a completely different vibe from Parikia. An authentic, full-on fishing port, where the boats were hauled up onto the bank to dispense their catch while the seamen mended their nets, where the locals seemed for once to outnumber the tourists. Not a favourite with the lager-drinking hoards, it was graced instead by bohemian intellectuals in studied flowing attire, looking for enlightenment and sardines.

I trawled around the castle walls of the old town with its spiderweb of tiny alleys, avoiding the main attraction of my visit – sweat breaking out along my neck every time I spotted a woman over five-ten with auburn hair – until I could stand it no longer, and made for the harbour.

But of Ellie there was no sign. And as I had suspected, the Tamarisk restaurant was a dead end. Yes, they’d heard of an owner who lived in Athens, but the only name they could give was of a certain Ella – an Italian who lived on the island and spent time between Naoussa and Paros, where she also managed a cocktail bar. Did they know if the owner in Athens was Ellie’s cousin? No idea. They had never heard of an Ellie.

Disappointed, yet determined to embrace the positive – I 24was cutting a new path, after all – I stayed for dinner and ate alone, watching the sun set. My table perched only five feet from the water’s edge, I let my mind empty and became mesmerised by phosphorescence in the shallows, which would flash up every time a wave surged onto the hissing sand; a hypnotic, almost erotic dance of light, urging me into the water to taste her deeper oblivion, if only I would dare. Then, as night thickened, came a boisterous live band, playing traditional Greek songs with bouzoukis and mandolins. Soul-searing music, sad and happy at the same time.

I assured myself that I didn’t need Ellie. I missed her – of course, I had to admit it – but missing her was acceptable. It was important to grieve, vital, even – to make way for the new. But I didn’t need her. I felt immediately lighter.

When the locals began to assemble and dance, I wondered if I was going to be invited to get up – which was when I caught sight of the only other non-Greek: a freckled, strawberry-blonde-haired girl trying to read a copy of Cider with Rosie at a table just behind me.

I asked if I could join her.

She obliged.

Her name was Charlotte Molenaar. She was Dutch, twenty-three years old, and worked at an investment bank in Rotterdam. We ordered a bottle of red and chatted about everything and nothing – from sea urchins, Greek food and sun cream to Swiss chocolate, Yeats’s poetry, and how to make a friendship bracelet, which she demonstrated by undoing hers and starting over from scratch. She gave it to me as a memento.

There was more wine and more music.

With every toss of her waist-length locks, she enraptured me further, inviting me into her playful worldview that was 25far, far removed from Ellie’s cool political savvy. Childlike in her wonder, she hung on my every word, from my teaching of the position of the Pole Star, the reliable, due-north centre point amid the relentless rotation of celestial bodies, to my recently acquired knowledge that one should only eat the purple sea urchins, not the black. And to top it all, she couldn’t get enough of my matchbox trick – creating an ‘erection’ using three matches that fused once lit, causing the middle match to rise in a woody tumescence.

Eventually we were dragged to our feet by the locals and joined in the dancing until the kitchen closed. Over the course of those brief, music-swept, wine-soaked hours, I fell in love. I wanted to drink her in, absorb her into my skin and leave a single set of footprints on the earth.

At 1 a.m. when the waiters kicked us out, we walked hand in hand to her hostel, where she asked me to wait while she fetched something from her room. I was itching to kiss her in the lobby, but thought she’d appreciate the privacy, so I suggested I accompany her to her lodgings. ‘It’s a sweet gesture,’ she replied, unhooking her arm from mine. ‘But James will be asleep and he hates being woken unnecessarily.’

I felt the ground tilt.

She returned with a book of Yeats’s poetry and told me I should read the one called the ‘Song of the Wandering Aengus’. With that, she smoothed down her dress, kissed me on the cheek and told me not to lose the friendship bracelet.

Then off she went to bed.

I sat in the shabby foyer of her hostel, wondering if ‘James’ was a safety net, and considered knocking on her door to find out, but couldn’t summon the courage. Finally, after fifteen minutes’ popping and cracking from ill-fated insects electrocuting themselves on the fluorescent flytraps, I left the 26hostel and set off back across the plateau under the canopy of a thousand frozen lights to my goat hut, the copy of poems wedged into my shorts.

When I reached the highest point on the mountain, I stepped off my moped, kicked it over into the dust and stamped against the unforgiving earth, screaming obscenities into the night until I was at risk of breaking an ankle. Then, in a final act of indignation, I hurled the anthology of poems as far as I could into the thyme.

Ellie was right: I was a loser.

The next day I was fired.

I left early for the depot, keen to rid myself of the sour taste from the previous night, and on arrival, found Leo with his arm in a sling and a fuming Kyros in tow. I asked the former if he was okay, but he wouldn’t even look at me. Kyros stepped forward, and clenching his massive fists, told me that according to Leo I had broken his arm by pushing him off his moped.

I was dumbfounded. Aside from the fact I’d never witnessed him ride a motorbike, let alone own one, the story was preposterous. But when I opened my mouth to demand exactly when and where this act took place, Kyros gave a dismissive wave of a hairy hand and turned his back on me in disgust. With that, they drove off and left me among the timber and scaffolding, utterly perplexed.

I couldn’t go to Roland for advice, as he’d upped and left the previous week for Santorini to get in some sightseeing before returning to Scotland, so I remained contrite and kept my mouth shut. Leo was a stout lad, and as I’d never had a proper fight in my life, I didn’t fancy my chances. Besides, being local, I figured he’d have connections.27

When I finally returned, shattered and humiliated, back at the goat hut, I discovered someone had been through my rucksack and stolen the 10,000 drachmas I’d hidden away in a rolled-up pair of socks. They’d also taken my gym shoes and a T-shirt.

I was fucked.

For the next four days, I trawled the main strip of Parikia in search of work – anything to try and get back in the game – but without success. At night, I moved from rooftop to beach to building site to find a secure berth where I could expect a peaceful night’s sleep, now my goat-hut hideaway had been compromised; and in a bid to eke out the remaining 3,000 drachmas, my diet was reduced to white bread and – when I could get away with it – the leftovers from other people’s plates.

Inevitably, I ran out of money.

In desperation, I slogged back and forth across the quayside into every restaurant and café, offering my services for the job that all the island workers loved to hate, kamakying, until finally, a Parisian chef agreed to give me a try-out the following night – unpaid, naturally; tips only.

That evening, I sat out by the lone church on the cliffs at Krios with my rucksack and watched the shooting stars, wondering what I’d do if I failed to make any tips. Put in a phone call to the parents – ask them to wire over some emergency funds? Out of the question. Aside from the fact I’d need identification to access the money, it was a question of pride. Hunter-gatherers didn’t phone home. Besides, I’d only worry them unduly.

What then?

Steal, most likely. It was either that, or go to the police, admit my stolen passport and loss of funds, put myself in the hands of the British Embassy and call the whole thing off.28

As midnight came around, unwilling to face the kilometre walk back around the bay, I pushed through the tiny chapel door into the cool interior and made use of the altar. Not the most comfortable of beds, but it was at least mosquito-free.

And yet sleep eluded me. If I couldn’t provide for myself, if I couldn’t guarantee food on the table, what use was I to anyone else? What right did I have to call myself a man?

As it turned out, I never made it to the restaurant, because the next day I ran into Ricky, the tattooed Australian, or, rather, he ran into me.

3

I had just finished using the Koula campsite shower to freshen up for my first night on the new job; the humidity had jumped over the course of the day and a sultry haze settled in above the island. Crossing the concrete apron between the shower block and the campsite entrance, I heard the screech of car brakes and turned in time to come face to face with an open-top jeep heading straight for me in a cloud of dust. I froze and awaited the impact, but it never came. The vehicle slammed sideways to a stop just inches from my feet as the engine cut out. ‘Haston, you Pommie bastard! I’ve been searching this island for days. Where the fuck have you been?’

Twenty minutes later we were pulled up on the edge of a shingle beach in the sleepy village of Pounta, four miles south of Parikia, smoking cigarettes as we listened to the ticking of the cooling engine. Ricky had insisted on taking me for a spin, promising to drop me off at the restaurant in time to start work at eight.

He was quick to dismiss my outrage at being abandoned on the ferry, and he also swore he didn’t have my passport 30or travellers’ cheques. According to him, I’d disappeared below deck for a ‘tactical vom’ and never returned. Seeing as Santorini was the last stop and I hadn’t reappeared, the gang had assumed I was either on Paros or Ios. Cracking on without me, they continued the party for several days straight in Fira, the stylish capital perched high above the cliffs. After that they parted ways.

‘Diane was gutted, mate,’ he grinned. ‘Fancied the arse off you.’

From the twinkle in his eye I couldn’t tell if he was bullshitting me – I figured the glint to be a permanent fixture – but I found his energy invigorating, and so, giving him the benefit of the doubt, I filled him in on my own little adventures – in particular, the strange incident with Leo ‘the Cunt’ – and enjoyed the sensation of catching up with an old friend, despite the fact we’d known each other for a matter of hours, much of which I couldn’t recall.

‘We should probably head to the restaurant,’ I said, noticing the time on the dashboard clock. ‘Chef’s Parisian – surly bastard. Don’t want to piss him off before I’ve started.’

‘No sweat,’ replied Ricky, flicking his cigarette across the bonnet of the jeep. ‘But mate, I got to show you something first.’

He spun the vehicle around and we rejoined the main road back to Parikia. About half a mile into the journey, we turned off up a dusty byway that took us up and over a wide network of undulating olive groves and sun-bleached farm terrain with its scrawny goat-herd inhabitants before turning south again and effectively doubling back on ourselves as we approached the northern edges of Alyki, the ancient fishing village once famous for its salt production – so Ricky told me.31

Bouncing along a track full of potholes, we approached a villa nestling among some cypress trees in the middle of a neatly laid out olive grove. It had a pristine ten-metre pool that looked over Alyki harbour below, and every meandering cuboid wall and turret was laced with climbing bougainvillea and jasmine, like a cover shot from a travel mag.

‘Don’t tell me you live here, you jammy bastard,’ I shouted to Ricky above the whine of the engine.

He didn’t reply, just grinned and continued fighting with the spinning steering wheel as we rolled up to the west side of the villa and parked alongside the patio steps.

I followed him around to the front of the building and he tossed me a set of keys. ‘After you,’ he said, gesturing to the ceiling-to-floor windows.

Expecting any minute to be surprised by an irate owner, I unlocked the doors, stepped over the threshold and wandered hesitantly in. Chequered marble flooring, antique furniture and Turkish tapestries spread out before me, leading up to a wide, open-plan kitchen resplendent with copper and steel cooking utensils hanging from elegant hooks on the wall behind low-slung industrial lamps.

‘What’s all this then?’ I asked, thoroughly impressed.

‘A proposition,’ replied Ricky.

I turned around to find him pointing the lens of his video camera at me.

‘Still got that thing?’ I said, getting a flashback from the ferry of him thrusting it in my face as Diane tried to put her tongue in my mouth.

‘Go on,’ he grinned. ‘Say something witty.’

‘I’m all right,’ I replied. ‘So, what are we doing here?’

But he ignored the question: ‘Sony camcorder,’ he said, pressing ‘record’. ‘State of the art.’ He filmed me for a 32moment, then without a word handed me the camera, sauntered back outside, stripped down to his pants and backflipped into the pool.

Keys in one hand, camcorder in the other, I walked out and stood by the edge as Ricky raced himself for a length of front crawl. Eventually he pulled himself up onto the side and shook his head, dog-like. ‘The villa belongs to a client of mine,’ he panted. ‘An artist. Travels the islands every summer so he can paint. I help him with his itinerary and organising his affairs; do a bit of this and that. He hires a yacht every year, which I help him source and occasionally crew for him. It’s a lot of work and I could use another set of hands about the place.’

‘Doing what, exactly?’

There was that glint again.