8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

BIG BUSINESS James Euchre lives an easy life as a local attorney in a small Texan town, making plenty of money from patent infringement cases. BAD BLOOD But when his mentor is killed, and one of his clients is arrested for murder, James is forced to take on his first criminal case - defending the man who allegedly killed his friend. BETRAYAL The deeper James goes into the case, the more he fears that he'll fail to save an innocent client's life - or worse, wind up freeing a guilty man...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

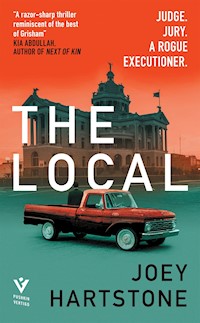

THE LOCAL

JOEY HARTSTONE

To Abby, my collaborator for a lifetime.

To Teddy, our collaboration of a lifetime.

CONTENTS

PART I

IN LOCO PARENTIS

In the Place of a Parent

· ONE ·

Small towns are defined by their secrets. Some are even haunted by them. There is a communal consciousness that remembers everything no matter how hard people may try to forget. You can’t keep a secret in a place like this, at least not forever.

Marshall is only forty miles from the state’s eastern border but still deep in the heart of Texas. Folks live and die with the Mavericks on Friday nights and seek salvation in church on Sundays. Since World War II, the population has remained unchanged at twenty-three thousand souls. It’s almost as if there’s no incentive to come here, but people can’t find a good reason to leave either.

We have an equal number of white and Black citizens, but the scars of inequality run deep. The ghosts of slavery and segregation still roam our streets. To this day, a statue of a Confederate soldier casts a shadow over the town square.

Behind the bronzed effigy of Johnny Reb stands the old Harrison County Courthouse. Its bright yellow facade, marble columns, and domed top make it our unofficial capitol building. Lawyers love a good courthouse the way players love a good ballpark. It makes us believe that our lot in life is more important than it probably is. The best lawyers in these parts, however, don’t work in this building.

Just beyond the hand-laid redbrick parking lot of the old county courthouse stands another building, another courthouse. It’s a simple beige-and-brown rectangle, thirty feet high, with small columns in front. Its demeanor suggests you need not notice it at all. This is the Sam B. Hall Jr. Federal Building, home to the US District Court. For the past twenty years, the Eastern District of Texas has been the epicenter of intellectual property law in the United States. It is Marshall’s best-kept secret.

For some reason that morning, as I sat at the plaintiff’s table with my client and a team of lawyers from the Chicago law firm of Rosewood & Barkman, I was overcome with a feeling of awe. It was the final day of my final trial for the calendar year, and I found myself in a moment of reflection. As I looked up at Judge Gardner’s wrinkled face, I couldn’t shake the idea that the kingdom he had built was as impressive as it was improbable, and that we all owed him a debt of gratitude.

There had been whispers around the courthouse for months that the judge was contemplating stepping down. People were even speculating that he would announce his retirement that night at the annual Christmas party. I dismissed these rumors as baseless because I believed he would have told me privately if that were his plan. Still, I’d had a sense lately that he was trying to savor certain moments as if they were passing by, never to return. As he glanced in my direction, I wondered if he felt a sense of pride. I was, after all, his protégé. He had crafted me in his image.

“Mr. Euchre?” Judge Gardner drew the court’s attention my way without revealing any affection for me. After I’d spent five days sitting quietly beside my client with nothing to do but ponder the wonders of our universe, the time had come for me to do what I’d been hired to do. I was going to deliver a closing argument.

“Thank you, Your Honor.” I rose to my feet but didn’t button my jacket. I walked toward the eight members of the jury in complete silence. It was the first time they would be hearing from me since they were selected, and I wanted to give them a few more beats. I found my mark and then hesitated, as if unsure of how to begin. Truthfully, I knew every word that was about to come out of my mouth. I was going to deliver my patented “Ford pickup” closing. As a matter of legal fact, a collection of words, such as a speech, cannot be patented but rather copyrighted. Suffice it to say, it was my favorite summation.

“When I was fifteen years old, the widow who lived next door to me decided to sell her late husband’s truck. It was a 1964 Ford F100 with a cracked windshield, missing fender, and dented grill. Its original Rangoon Red paint job, which perfectly matched the high school’s colors, was peeling and had faded under the sun. It was the most beautiful vehicle I’d ever seen.

“I struck a deal with the widow. In one year, I would buy that truck for twenty-four hundred dollars. Bagging groceries at the Kroger for three thirty-five an hour wasn’t going to cut it, so I got a paper route and started mowing lawns on the weekends. I took any odd job I could find, and for one year, I didn’t spend a penny unless I absolutely had to. Where most boys would keep a picture of their girlfriends in their wallets, I had a photo of this old truck, a reminder of what all the hard work was for. The best day of my young life was when I emptied out my savings account, handed my neighbor all twenty-four hundred dollars to my name, and became the proud owner of a Ford pickup. When I got behind the wheel, a feeling of achievement washed over me. I’d never felt that way before.

“Two weeks later, I stepped outside my home with the keys in my hand and discovered that the driveway was empty.” I paused here, as if overcome by the memory.

“I’m embarrassed to admit how many minutes passed before I accepted the reality. I’d never owned anything, and now my one possession in the world had been stolen. For weeks, I kept my eyes peeled, hoping I’d spot my Ford abandoned somewhere, just waiting for me to rescue it. Then one day I get a call from Detective Elliot. He says they think they may have found it up in Marion County, but before they go and accuse someone of grand theft auto, they want me to confirm that it is indeed mine.

“So Detective Elliot drives me to Marion, and we pull up to this ratty old house with weeds for a yard, and there, parked right in front for all the world to see, is a 1964 F100 with a cracked windshield, missing fender, and dented grill. I jump out of the cruiser and run up the driveway. Just then, a man in his twenties comes out of the house and hollers at me to get off his porch. I move right to him, fish my wallet out of my pocket, hold the photo of the Ford up in his face like it’s a police badge, and declare, ‘My name is James Euchre, and that is my truck!’

“The man looks at the photo and then back at me and says, ‘That can’t be your truck. Your truck is red. That truck right there is black.’” I paused again, allowing the audacity of this comment to infect my listeners.

“Not only had this man taken my vehicle, but now, caught dead to rights with my property in his possession, he had the nerve to deny everything because, after he had stolen my beloved truck, he had covered that original Rangoon Red body with a cheap coat of black paint.”

For all of the flaws in our legal system, the one thing that we got right was entrusting ordinary people to dispense justice. Even in a field as complicated as intellectual property law, we put our faith in common citizens. Patents can be incredibly complex. It often takes an advanced degree in electrical engineering or microbiology to understand how something works, let alone whether or not the idea behind it was taken from someone else’s design. The lawyers from the firms on both sides of this case had spent the past five days asking these jurors to think. In my first five minutes, I had asked them to feel.

Every one of us has a different capacity to understand information based on who we are, what the subject matter is, and how our education and intellect relate to the issue at hand. What makes us alike, what makes us human, is that we all experience the same range of emotions—the same fear, the same love, the same rage. My job was to distance the jurors from the complicated facts of the case and remind them how it feels when someone takes what is rightfully theirs.

I loved my Ford closing for a lot of reasons, but principal among them was that it genuinely enraged me. By the time I was done talking about the bastard who stole my truck, my own blood was boiling. And emotions are transferable. Of course, I would ultimately bring my discussion back to the issues at hand, but not until every one of those jurors was thinking about their own experience of being wronged—that time someone hit their car and didn’t leave a note, the day their boss took credit for their hard work, that moment when they were victimized by a faceless thief, never to be made whole again. Once that courtroom was overflowing with rage, I turned our collective attention to my client, the plaintiff who was wronged in this case, and I gave the jurors the power to make it right.

I stepped toward the plaintiff’s table. Typically, I represented corporations, but in this case, my client was a home economics teacher with arthritis from Skokie, Illinois. Over the years, as Marta Sexton’s condition had worsened, her doctors had prescribed her more and more medication. One day, her hands were in so much pain that she could no longer open her childproofed pill bottle. Frustrated but not defeated, she conceived of a new design for a medicine container that didn’t take much force or a strong grip to open but was still impenetrable to a young person’s inquisitive paws. Inspired by a combination lock on a high school locker, she sketched a design that required a person to line up three designated spots on the pill bottle with three corresponding points on its twisting cap. Once all three arrows on both components were aligned, the top would lift off easily. It was something that any patient could use and no child could hack. Thankfully, Mrs. Sexton filed for a patent.

The United States Patent and Trademark Office is located in Alexandria, Virginia, and is an agency within the Department of Commerce. If you have an invention, or if you have a design for an invention, or if you have an idea for a design for an invention, you can apply for a patent. If someone or some company infringes on that patent, you can sue them in federal court. Which federal court? That’s the billion-dollar question.

One day, Mrs. Sexton was walking through the Hartsfield-Jackson airport in Atlanta when she stopped at a kiosk that sold phone chargers, candy bars, and other travel accessories. On one of the shelves was a variety of medicines. She thought it would be a good idea to take an aspirin before flying. So she bought a bottle of pills and some water and went to her gate. As she prepared to board, she removed the pill bottle, and lo and behold, it was childproofed. To the untrained eye, it may have looked like any other medicine container. But my client saw something different. She understood the specs, the modifications, and every working component of this little plastic contraption right down to the familiar three-part locking mechanism. Her blood, sweat, and tears had gone into inventing this design that someone, or rather some company, had stolen. When her plane landed at O’Hare, her first call was to Rosewood & Barkman.

The company that created the medicine was headquartered in upstate New York, while the pill bottle itself had been manufactured in a factory in Seattle. It was well within Mrs. Sexton’s rights to file her patent infringement suit in either the Northern District of New York or the Western District of Washington, but that was the opposition’s home turf. She also could have filed suit in the Northern District of Illinois, her own backyard. All of these options would have made a lot of sense since these were the venues where the item was invented, where it was stolen, and where the company that profited was based. But what about the Atlanta airport? When an employee at that kiosk put one of those products on their shelves, a product that contained my client’s intellectual property, that was an act of patent infringement. Of course, she wasn’t going to sue the owners of a little kiosk because they don’t have deep pockets, but that didn’t matter. What mattered was this: a lawsuit can be filed any where in the country that a single act of patent infringement has occurred. Since Mrs. Sexton was the wronged party, it was her choice where to file suit. With all the kiosks in all the airports in all the country, the options were almost limitless. The best option though, at least for the past twenty years, has been the Eastern District of Texas. The reason is Judge Gardner.

Gerald Gardner was born on March 24, 1944, down the road toward Kilgore, next to the old ghost town of Danville, Texas. He grew up playing baseball and football like most boys, but his true passion was acting. He enrolled at Southern Methodist University in 1962 and found his home in the theater department. His favorite professor encouraged him to pursue his craft professionally, but Gardner replied, “I have no interest in going to Holly wood or Broadway and I doubt either has any interest in coming to Texas.” Not wanting his theatrical training to go to waste, Gardner chose to stay at SMU and earn his law degree.

Good lawyers are performers. It’s not an act, which is to say that it’s not fake, but there is an element of show to it. Gardner turned examining a witness into a mystery. Every closing argument was a soliloquy. People would travel from neighboring counties just to watch him in a big trial. One time, a court even handed out popcorn. True story.

Every law firm from Houston to El Paso tried to recruit him, but he didn’t want to work for anyone else. He was content taking whatever clients happened to come his way in East Texas. He was also adept at creating opportunities seemingly out of thin air.

One such job involved an oil and gas company from Lubbock that needed to resolve a land rights issue. It didn’t bring in significant business, but Gardner secured the deal and managed to impress the executives, one of whom was a young man by the name of George Walker Bush. Decades later, when a federal judgeship in East Texas became available, one of our US senators recommended Gerald Gardner. President Bush nominated him the following Monday.

To say that Gardner was inheriting an unimportant venue would have been an understatement. The Eastern District wasn’t exactly a hotbed of criminal activity or major litigation. But Gardner wasn’t the type of person to rest on his laurels. The dearth of cases was a blessing because it gave him the freedom to reinvent his court how he saw fit. In his entire career as an attorney, Gardner had only had one patent case. It was, as patent trials tended to be, a clusterfuck. But where there was chaos, he believed he could create order.

Judge Gardner overhauled the whole trial process. First, he allowed for broad discovery of materials so that lawyers couldn’t drag things out indefinitely with pretrial motions. Second, he set trial dates in stone. There would be no delays, no excuses. More than a few attorneys had to miss the births of their children so that they could appear in Gardner’s courtroom as scheduled. And third, he limited the lengths of the trials themselves. In most jurisdictions, a typical patent case could last weeks, sometimes months. But Gardner believed, “If God can create the universe in six days, surely we can finish a patent trial in less time.” Five days was his limit.

With these changes, EDTX had the capacity to become one of the most efficient and effective courts in the entire country. It took a little time, but eventually the legal world realized that the new judge had designed the perfect place to sue for patent infringement.

So where did I come in? Lawyers are licensed to practice law in specific jurisdictions, namely in the state or states where they have passed the bar exam and where their law firms are based. When a case takes lawyers out of their jurisdictions, they need to add someone within the new state to the team. That someone is called local counsel.

A local can do as much or as little as the rest of the team demands. Often, a local counsel does nothing more than advise the team on any unique quirks of that particular venue and serve as a signatory on any documents that need a regional John Hancock. All of this can be done for a nominal fee. Clients may never even realize that a local is on their team. That’s how it used to be in Marshall. After all, intellectual property law is complex, and no one in East Texas had ever tried a patent case. Lawyers here, though, had other skills that aren’t taught at top ten law schools. It didn’t take long for white-shoe law firms to discover that something was missing, something essential that local counsels could provide.

Here’s a scenario that happened too many times to count. A twin-engine Cessna Citation with the inevitable moniker “Law Firm One” touches down at the quiet Harrison County Airport. Six attorneys step off their firm’s jet, all wearing bespoke suits purchased on Madison Avenue. A private car, probably from Dallas, picks them up and drives them five miles, past broken fences and run-down trailers, into town. They march into the courthouse with Italian leather briefcases and polished expert witnesses. A casual observer may understand that this doesn’t go over too well with our juries, but rich and powerful people often lack self-awareness. There was a major disconnect between our humble citizens of Marshall and these corporate attorneys from big cities. To make matters worse, some of these people thought they could fake their way into the good graces of the jurors. I’ve seen out-of-town lawyers go straight from the airport to the Boot Barn on Pinecrest Drive, buy a pair of shiny new Buckaroos, and then walk their blistered feet into court as if they’ve just come from the ranch. Mistakes like this have cost clients millions.

The top patent law firms around the country began to realize that what was missing from their teams was someone who spoke the language, someone who could connect with the eight citizens on the jury. The more we locals were asked to speak, the more the jurors seemed to listen. Locals, who for so long had been undervalued and underused, were finally being called upon to perform an indispensable service. Like strong pinch hitters and clutch relief pitchers, our roles were small but vital. And we began to be paid accordingly.

So it came to pass that the best trial lawyers were not in Houston, Austin, or Dallas but rather in a small corner of the state, practicing an area of law that none of us had ever studied, working on cases worth tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars. We were the final component to a billion-dollar industry, a magnificent legal universe created by one visionary judge in Marshall, Texas.

· TWO ·

I concluded my summation and returned to my seat, where I would spend the rest of the morning watching an attorney for the defense deliver his closing argument. My work was done, and I felt it had gone well. I’d made the desired connection with the jurors and hoped I’d left them with the feeling of rage. If all went according to plan, they’d deliberate swiftly, return a verdict in favor of my client, and award her a nice chunk of change.

Once this case was completed, I would have five weeks of nothingness in front of me, as December faded into January. After remaining relatively sharp and clear-eyed for the trial, my plan was to drink my way into the darkness and emerge in the new year rejuvenated, even if I would be a little worse for the wear. If the verdict was good, my night would inevitably begin with a champagne celebration. If it was bad, I’d crack a beer and begin my descent alone on a barstool. Either way, I’d end the night with a solitary bottle of whiskey that was waiting for me at home. I had a feeling I’d be tasting the bubbly before the night was through.

During my closing, I had noticed a familiar face in the rear of the courtroom. I spun around in my chair to take a second look. Abraham Rabinowitz, a top lawyer from New York, was sitting in the last row. He was dressed sharply and his silver locks, despite being wet and combed back, were beginning to break free into their natural state, which resembled a lion’s mane. On either side of him were a man and a woman whom I did not recognize, though I assumed were his clients. They were both considerably younger than he was. I gave Abe the slightest wink, and he nodded back. Whatever he wanted would have to wait until the next recess.

The defense gave a ninety-minute closing argument, during which I saw two jurors nod off. It was an unceremonious conclusion to a case they hadn’t presented particularly well. The court reporter distributed Gardner’s written instructions to the jury. Someone along the way had screwed up because there were seven copies instead of eight.

“Don’t worry about mine, Judge,” said Juror Number Three. “I can’t read none any way.”

The Chicago lawyers couldn’t hide their contempt. A complicated patent design and a verdict worth millions were about to be in the hands of eight people with six high school degrees between them, one of whom was apparently illiterate. It was classic EDTX, and I loved it.

“Well, you’d better listen extra close then, sir,” said Judge Gardner. His Honor read the instructions aloud, and then the jury retired to the deliberation room. There was nothing left to do but wait.

As I expected, Rabinowitz motioned for me, and I held up my index finger to let him know I’d be there in one minute. Abraham Rabinowitz, or “Honest Abe” as I liked to call him, was a top litigator at the Manhattan-based firm of Gordon & Greene. He couldn’t have looked less like Abraham Lincoln if he tried. He was a short man whose midsection was shaped remarkably similarly to the matzo balls his mother used to make. Originally from the Brownsville neighborhood in Brooklyn, Abe was, to me, the quintessential New Yorker. I called him “honest,” but more accurately he was blunt. He simply didn’t have time for bullshit. I admired him for this, and our juries often embraced him because he didn’t pretend to be anyone other than his authentic self.

Abe’s firm specialized in intellectual property law, so it handled a lot of cases in Marshall, and while he used the services of a few locals, I was Abe’s favorite. We shared a similar perspective on how the game should be played and an appreciation for the other’s roles in it. We also won a lot more than we lost.

As I approached him, he stepped away from the man and the woman with whom he’d been sitting so that we could speak alone.

“Jimmy! You looked good out there today.”

“Thanks, Abe.”

“I give it a nine-point-three. You started out strong, but you didn’t stick the landing.”

“Everybody’s a critic.”

“I grade you on a steep curve.”

“I didn’t know you were in town,” I said, putting an end to my performance review.

“Just for the day. We have an eligibility hearing this afternoon.”

“In front of Gardner?”

“It was supposed to be downstairs with the magistrate judge, but since you guys have this wrapped up early, maybe Gardner will hear it after all.”

“Those are your clients?” I asked, motioning to the couple in the back, who looked uneasy in their unfamiliar surroundings.

“He’s the client. She’s new to our firm.”

At second glance, she did dress the part of an attorney. I should have pegged her as a lawyer. Despite the fact that half of the prospective jurors in Marshall were Black, it was still rare to see a Black attorney in EDTX. Aside from general racism in hiring, the prevailing “wisdom” was that a Black attorney was more likely to alienate our white jurors than gain the support of our Black ones. It had taken an embarrassingly long time for firms to finally begin to reject this theory. In addition, the firms that had expanded their hiring practices were discovering not only the benefits of diversity but also a great deal of untapped talent.

“Any chance you can join us for lunch?” Abe asked.

I looked back at the plaintiff’s table with Mrs. Sexton and the Chicago lawyers. I’d been eating with them all week and was getting tired of hearing about how much better the food was in the Windy City.

“I’ll see if I can sneak away.”

Abe leaned in toward me. “This client’s going to be spending a lot of time in Marshall.” That was music to my ears. I preferred representing plaintiffs, but a defendant who gets sued repeatedly can bring in a lot of business. I nodded, letting Abe know I’d make it to lunch one way or another.

“Hey, Jimmy, let me ask you something.” I stopped and waited for his question. “Did you ever actually own a Ford pickup?”

I grinned. Not a lot of people would have had the balls to ask me that outright. “Come on, Abe. All the best stories are true.”

I broke off from the Chicago lawyers and exited the federal courthouse. As I walked across the brick parking lot, I spotted the district attorney, D. Calvin Lucas, and two of his underlings heading toward the old Harrison County Courthouse. “This must be where the real lawyers are at,” I said as our paths crossed.

“It’s not patent law, but we can’t all do God’s work,” replied D-Cal, as those of us who’d known him since grade school called him. He was a special breed of asshole. He was a born politician, and everyone expected that the DA’s job was just a stepping-stone to his higher aspirations. I figured he was a good enough attorney, but he suffered from big-fish-in-a-small-pond syndrome. He was a prosecutor in a town with no crime. In another universe, Lucas and I could have been good friends. In this universe, though, we’d been competitive for far too long to be anything but adversaries.

“Best of luck taking down the shoplifters and jay walkers, D-Cal,” I said as I continued on my way.

I made a quick stop at the little tobacco shop just off the square. A box of Dominicans was on display next to the cash register. By the smell of it, I suspected a customer had extinguished one only a few minutes earlier. The smoke was gone, but the sweet scent lingered. I asked the clerk for a pack of Marlboro Reds and a plastic lighter. I’d retired from being a full-time smoker years ago, but I treated myself to one pack at the end of every trial. I was overpaying by buying them there, but I liked the atmosphere. The clerk handed me my cigarettes and a pink lighter.

“Sorry, that’s the only color we got left,” he said.

I rolled my thumb down the spark wheel and watched the flame come to life. “The fire’s still orange,” I replied.

As I walked the side streets, I kept thinking about the deliberation room. Juries are the great enigma of the trial process. Anyone who says they can confidently predict which way a verdict will go is full of shit. Juries are as varied as the people that comprise them. Still, there are patterns that can emerge. About two years into Gardner’s tenure, the new judge had overhauled his court, but no one had really noticed yet. Then a big piece of the puzzle fell into place, one that would solidify EDTX as the ideal venue in which to sue for patent infringement. That piece happened to be the juries.

Out in Fort Worth, around the turn of the twenty-first century, lived an eccentric inventor named Neil Sampson Carlyle. Carlyle worked in his shed, sketching elaborate designs for new devices and thinking up ways to improve upon old ones. One cloudy April day, inspiration rained down on him, literally. A monsoon tore into town, and Carlyle’s ratty old roof was no match for the torrential downpour. He ran around placing buckets and bowls under every leak in the ceiling. When the storm broke, he climbed up on top of his house and discovered that the wood-shingled roof looked like Swiss cheese. He’d been doing some sculpting work with lightweight concrete and decided to repurpose the material for roofing. He covered his house with new shingles he’d made in his shed. The next time it rained, his house remained bone dry.

Carlyle set a meeting with a major building supply chain based out of Dallas. He showed some samples to the executives, did a demonstration with a garden hose, and assured them that this composite concrete could be the future of roofing technology. They were interested and said they’d think about it, but a month later they passed on the product. Carlyle forgot all about it and moved on to whatever else popped into his mad-scientist brain next. Two years later, Carlyle was out walking his Australian shepherd, Elroy, when what did he see? A neighbor’s house had a brand-new roof made of lightweight composite concrete. He had a hunch about which company had manufactured the materials. Turned out, he was right.

Carlyle hired a lawyer, and they went to file their suit in Dallas but were told there was a backlog of cases and they should expect to wait at least eighteen months just to get into a courtroom. The lawyer did some digging and came up with a list of about twenty cities and towns where the company had sold this roofing product. One of them was Marshall, Texas.

Carlyle’s suit was filed in the Eastern District. Judge Gardner granted broad discovery of the company’s documentation, R&D work, and financial records, and then set a trial date. One look at a side-by-side comparison of Carlyle’s patent and the company’s new product, and you didn’t have to be an expert in carpentry to conclude they were identical. Moreover, not only did Carlyle clearly own the patent, but he had made detailed contemporaneous notes about his meeting with the company’s executives, right down to the many questions they asked him about how the product was made.

After a four-day trial, the jury retired to deliberate, and the building supply company sensed impending doom. Carlyle’s lawyer was asking for $4 million in damages. The attorneys for the company met in the hallway and convinced their client to offer $1 million to settle the case and another $1 million to buy Carlyle’s patent outright. Carlyle decided to roll the dice and take his chances with the jury.

It took the eight jurors a little over an hour to reach their decision. As the foreman would later recount, “We knew the verdict right away. The real discussion was about the amount.” The jury found that the company had infringed on Carlyle’s patent, and then, in what became the shot heard round the patent litigation world, they awarded Carlyle damages in the amount of $70.2 million. Where the .2 million came from, we’ll never know. If you ask me, it was just an added “fuck you” to the man.

Word of this massive award spread throughout the intellectual property law community, and Gardner’s docket was quickly flooded with patent cases. Everyone watched closely to see if Carlyle’s verdict was an outlier. Turned out, it was the norm. One by one, plaintiffs in EDTX were not only winning their patent cases, but they were also being awarded ungodly sums of money. This created a gold rush.

Lawyers, politicians, hell, even sociologists would spend the next decade trying to explain what was going on with these juries in East Texas—they were not only unusually sympathetic to plaintiffs in patent cases but were also prone to delivering verdicts with huge dollar amounts. Thousands of legal articles and dissertations were written on the subject, but it all boiled down to this: when people who are overlooked for their entire lives are given a modicum of power, they will wield it with great force.

There was a stampede to EDTX. Nearly every plaintiff in the country wanted to file suit in the Eastern District. Most courts wouldn’t have been able to handle the influx of new lawsuits, but thanks to the way Judge Gardner had rewritten the rules, his venue was designed with efficiency in mind. The speed with which Gardner’s court burned through patent trials became legendary, and it earned his court’s calendar the nickname the “Rocket Docket.”

· THREE ·

I spotted Honest Abe seated along the near wall of Central Perks. It was a short walk back to the federal courthouse if the jury reached a quick verdict. I had hoped this meeting would be a short one. Ordinarily, Abe would have simply asked me to join him on a case, but apparently this particular client had insisted on vetting me first.

Abe embraced me with the warmth of an old friend. “Jimmy, allow me to introduce you to Mr. Amir Zawar. Amir, this is James Euchre, the best lawyer in Marshall.”

“Nice to meet you, Mr. Zawar.” I shook his hand. He was at least a few years younger than I was and, I suspected, tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars richer. At about five feet ten inches, he looked to be very physically fit though not overly muscular. I pegged him as the type to be more fixated on his core strength than the size of his biceps, a lesson he surely learned from his personal trainer.

“And this is Layla Stills,” Abe said as she rose from her seat with determination and shook my hand firmly. She also seemed to be in great shape, though given her line of work, her exercise regimen was probably limited to running on a treadmill while reading legal briefs, or some other activity that allowed for multitasking.

“A pleasure, Ms. Stills.”

“Layla joined us at Gordon & Greene last month.”

“It’s always nice to meet a new associate,” I said.

“I’m counsel, as a matter of fact.”

The difference meant something, and I liked that she felt compelled to highlight it. She, too, was probably a couple years younger than I was. If she had joined Gordon & Greene on the partner track, she must have had an impressive résumé.

“Is your background in IP?” I asked.

“Criminal law,” she answered.

Abe jumped in. “Layla was an AUSA in DC for seven years. She’s got more time in court than you and I combined.” I admired the way he always looked out for his people.

I took a seat across from Amir. Layla sat beside him while Abe positioned himself at the head of the table, between me and his client.

“So what brings you to Marshall, Mr. Zawar?” I needed to get the meeting started.

“It’s not your Southern hospitality,” he said with more than a hint of indignation. This didn’t faze me. No one likes being sued, and most clients despised being sued in EDTX.

“Jimmy, Amir created a company called Medallion. There was a big profile last month in The New Yorker; maybe you saw it?” I shook my head. I didn’t want to insult the man by admitting I hadn’t heard of him, but it was better not to begin with a lie. “Why don’t you tell him about it, Amir?”

“My father came to this country from Karachi, Pakistan, when he was nineteen years old. He drove a taxi in New York City for almost four decades. He worked every day of his life to earn his piece of the American dream.” As Amir described his background and highlighted the pertinent details that would become ingredients for his future business ventures, I figured he’d told this story before. But it didn’t feel overly rehearsed. His occupation was more than a job; it was a calling. I was also struck by Amir’s sincere admiration for his old man. It was a feeling so foreign to me that I had to remind myself that his was authentic.

Over the next ten minutes, Amir told me all about his father’s life. He had arrived in New York in the early eighties and found work driving a cab. For a quarter of a century, he saved every dollar he could with two goals in mind. The first was sending his son to college. The second was one day becoming his own boss. For a driver in the Big Apple, that meant owning a taxi medallion.

The city of New York issued a limited number of medallions and you couldn’t drive a cab without one. As the years passed and the population grew, medallions became more and more valuable. By the twenty-first century, a taxi medallion was seen not just as a license to own a cab but as a piece of equity that would appreciate over time. Most medallions were controlled by a handful of companies, but if an individual driver could scrape together enough money to buy one himself, it could be his ticket to financial independence.

“In 2006, my father took out a loan and purchased a medallion, using all of his meager savings for the down payment,” Amir continued. “He was, in his mind, working for himself now. He had to make loan payments every month, but this was just like paying the mortgage on a house. Eventually, he would own it outright, or so he thought.”

Wherever there is honest money being made there are dishonest people scamming for their unfair share. The predatory loans in the medallion industry put the housing loans of that era to shame. Amir’s father, like so many, was an easy mark for those unregulated companies awarding loans to mostly immigrant drivers, some of whom couldn’t read the English in which the loans were written.

“For the next eight years, my father took in $6,000 per month, $4,500 of which went to paying off his loan. It was steep, but at least the value of the medallion was going up. He had purchased the medallion for $650,000. Eight years later, they were going at auctions for $1.1 million. So my dad’s net worth rested not on his income but rather on what percentage of his medallion he owned. Tragically, he would discover that he didn’t own it at all.”

Amir’s father had unwittingly been put on an interest-only loan payment plan. In eight years, he hadn’t paid off a single dollar of the principal. To make matters exponentially worse, right around the time he and scores of other drivers like him were discovering the truth behind the shady loans they’d signed, the bubble burst. Medallion prices that had skyrocketed for decades began to plummet. The lucky drivers were the ones who got out just in time, defaulting on their loans and simply walking away with nothing. The unlucky ones were on the hook for million-dollar loans while their medallions were suddenly worth less than a third of that. They were underwater with no hope of resurfacing. Savings vanished, and families were ruined. More than a few drivers took their own lives. Others, like Amir’s father, were simply broken. His health declined rapidly as the bills piled up and threats of foreclosure weighed heavily on his mind. By the time he passed away, he had become a shell of his former self.

“Predatory lending I understand, but what caused the bubble to burst?” I asked.

“Uber,” said Abe, who hadn’t spoken for several minutes.

“Rideshare apps,” Amir clarified, “did massive damage to the taxi industry. Men like my father had been the lifeblood of cities like New York. Then, almost overnight, they were kneecapped, undercut by Silicon Valley.”

If I had read the profile in The New Yorker, I would have known the rest of the story. Amir had three semesters at Caltech under his belt when his dad’s financial problems began. Unable to cover tuition, Amir was forced to drop out. He managed to find work as a programmer in California, though. Then, after he buried his father, Amir had an idea.

“I created Medallion because I believe that the gig economy must embrace the people it generally displaces. My mission is to build an organization that welcomes in workers like my father.” As a general rule, I didn’t like Silicon Valley bros, but I had to admit that Amir was a compelling figure.

“I saw that Uber and Lyft were decimating the taxicab industry in cities all across America,” he continued. “So I developed an app that would give customers the convenience of a rideshare service with the reliability of a professional taxi company.”

“Doesn’t New York City already require a special license for rideshare drivers?” I asked, failing to see the novelty of the idea.

“That’s merely a way to limit the number of cars on the streets,” Amir responded, “but to the customer, there’s no difference at all. You’re still likely to end up in the back of a college student’s beat-up Hyundai Sonata. There are passengers who want a truly professional experience, from the driver behind the wheel to the vehicle itself. The problem is that it’s more convenient to order a car from your phone than to stand on the street and hail a cab. What Medallion does is take licensed taxi drivers and their cabs and transform them into a rideshare service. Operators can drive as they usually would, picking up random passengers on the street, or when they want assistance finding customers, they can turn on the app and be paired with riders. Rather than displacing an entire sector that helped build this country, we made taxi drivers an essential component of our service.”

It was an ingenious twist on a popular idea. It was also the kind of alteration to protected intellectual property that so often found itself on the wrong end of a lawsuit in Marshall.

“So what can I do for you, Mr. Zawar?” I asked, hoping to get down to brass tacks before I had to return to court. Instead of answering me, he looked at Abe to respond.

“Several suits have been brought against Medallion. Today’s hearing involves the first of many. The claimant is a software company called Astral that designed a navigation program that, it claims, Medallion’s software infringed on. We’ve got an eligibility hearing this afternoon, and trial is set for April.”

“If there is a trial,” added Amir.

My eyes met Abe’s. This client was hopeful. Someone needed to administer a dose of reality. Abe ran his hand through his long hair, an unconscious gesture intended to lower his blood pressure. “That is one thing we wanted to discuss with you,” Abe started. “Amir is insistent that if the case is not dismissed today we should ask for a change of venue.”

A motion for a change of venue can be brought for a variety of reasons, but typically lawyers do this when they believe that a case either belongs in a different jurisdiction or that the jurisdiction in question cannot render impartial justice because of some inherent bias. Patent defendants have been complaining about being sued in EDTX for twenty years, but changes of venue were never granted. They also irritated Judge Gardner.

“You don’t want to do that,” I said. “It’ll be denied, and you’ll insult the judge.”

“So if the case isn’t dropped today, we just accept that we’re going to trial?” Amir asked.

“The case won’t be dropped, Mr. Zawar.” It wasn’t what he wanted to hear, but it was better to be honest with a client, especially when he was only hours away from discovering that I was right.

“A lot of good it does having the best lawyer in town.” Amir’s tone changed, no longer attempting to conceal his contempt. “What does that title get you, any way? A blue ribbon at the county fair?”

“Amir,” Abe said, “let’s keep going.”

“Medallion has no affiliation with this town,” he continued. “I’d never even heard of this place until I got sued. My company doesn’t do business in this shithole. So can we at least stop pretending that my presence here is in any way appropriate?”

Amir’s grievances were nothing new. Medallion was joining a club of frustrated defendants from companies like Apple and Boeing to Xerox and Zappos. None wanted to belong to this group, but most had accepted that there wasn’t much they could do about it. It was the cost of doing business in America.

“I understand that no one likes being party to a lawsuit, and it compounds your resentment when it takes you away from home. But patent litigation is our specialty,” I said, referring to the collection of lawyers at the table, “so you should take some comfort in knowing that you’re in good hands.”

“Medallion has a pilot program in eight cities right now. By Q3 of next year, we will have doubled that. I should be tending to the demands of my business, not wasting away here in Mayberry getting sued by every rideshare company and navigation software developer from Silicon Valley,” Amir said. “My father busted his ass to try to get ahead. He did everything that was ever asked of him, and then the system screwed him over. I won’t allow that to happen to me.”

There were two sides to Amir Zawar. The first was the creator, the visionary who had founded a burgeoning empire that would have made his father proud. The second was the defendant, the man who resented being accused of theft and whose business was under attack. Amir seemed to switch from one to the other as easily as a faucet turns from hot to cold. There was a chip on his shoulder, and it clearly motivated him to succeed. It also told him to fight when his back was up against the wall. I found myself drawn to him, though the fact remained that my least favorite part of practicing law was the clients.

“Look, Amir, I hear what you’re saying. Your frustration is understandable. But you’ve got to let Abe do what he does best. Start with the eligibility hearing. It almost certainly won’t go your way, but then you’ll have a Markman hearing. That will determine the meaning of the terms in the patent itself and, if that goes well, might even dissuade others from filing similar suits against you. There are several battles along the way before we ever get to trial. So my advice is to keep your head about you and to let your legal team do what it was designed to do.”

“And I should make you part of this team?” he asked.

“Well, you’re going to need a local counsel—”

“Because Abe doesn’t speak hillbilly?” Amir asked.

I let out a little smile. “Actually, Amir, here in Marshall we speak redneck. Hillbilly is a dialect you’d find farther east. But to answer your question, yes, it will benefit you to have someone with my skill set at your disposal.”

“And how much is it going to cost me to have you persuade your ignorant neighbors by making a little speech about your missing truck?”

Amir wasn’t the first person to call into question my value as local counsel. As he would find out either the easy way or the hard way, though, a local was absolutely essential to his defense.

“Everyone seems to forget that simple people know the rest of the world thinks they’re simple,” I said. “Consider this for a moment, Amir. Any time we have an election in this country that breaks in a way no one expected, experts from LA to New York are baffled by these unpredictable swing voters. It always makes me wonder, if you’re all so fucking smart out there on the coasts, and we’re all so fucking simple down here, why can’t you figure us out?” This wasn’t my normal sales pitch, but Amir didn’t strike me as a typical client.

“Jurors are human lie detectors,” I continued. “They instinctually sift through all the jargon and all the bullshit to get to the core of a case. They’ll never fully understand how your software crowdsources users’ geotracking to provide optimal real-time navigational routing. It will never be clear to them whether the interface of your app is novel or if it was built by replicating entire blocks of code pilfered from other rideshare programs. But you’re right about one thing, Amir. The fate of your company will ultimately be in the hands of ordinary citizens from Marshall, Texas. They won’t trust you one bit, and you shouldn’t trust them either. This has been my home since I was a kid. Marshall is in my blood. I will be your advocate. It will be my job to make sure that they see you as a man who built his own company from the ground up rather than as a thief who took something that didn’t belong to him in the first place. They will trust me, Amir, because they are me, and I am them.”