Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: The Yorkshire Murders

- Sprache: Englisch

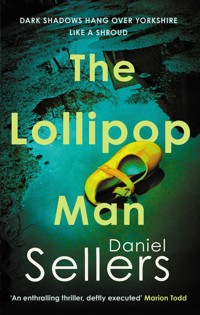

'Clever, complex and memorable, this is an unputdownable crime thriller. It kept me gripped right up to its pulse-racing final act' B P Walter 1994. Adrian Brown works at the local paper, haunted by his past and with good reason. Eight years ago, he was kidnapped by the Lollipop Man, a shadowy figure linked to three missing Yorkshire children. Adrian was the only one who escaped. Now another child has gone missing in circumstances that chillingly echo those disappearances years ago. As public fear mounts and the media fans the flames, journalist Sheila Hargreaves, burdened by her past reporting on the abductions, is determined to uncover the truth and finally bring the Lollipop Man to justice. 'An enthralling thriller, deftly executed' Marion Todd Slow-burn suspense, building to crackling tension and breathless pace - with an incendiary finish' M.K. Murphy 'Swift paced and cleverly plotted...Both shocking and moving' Cath Staincliffe

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 455

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1

2

3

THE LOLLIPOP MAN

DANIEL SELLERS

4

5

For Laura6

Contents

1

Wednesday 6th April, 1994

The call came while Adrian was eating Scampi Fries and waiting for Nige to finish his third pint in the Golden Lion. His satchel burst into a bleeping version of ‘Whistle While You Work’,bringing gawps of disgust from the old men hunched about the bar. He dived for the exit, wiping his orange-stained fingers on his jeans, and pulled out the phone’s stumpy aerial.

‘Adrian?’

‘Hi, Linda. Just a sec.’ The signal was dodgy so he moved to the edge of the pavement, as if that might help. It was raining hard and he hunched against it.

‘Are you still in Halifax?’ There was a note of stress in the newspaper editor’s voice.

‘Yeah, we’re still here.’

‘Is Nige with you?’

‘He’s – erm, he’s …’

‘In the pub, is he?’ A sigh. ‘Adrian, you don’t need to cover for him. Just go get him, will you? Then head over to Toller 8Bridge. Police have found a young girl’s clothes by the canal.’

‘Right,’ he said, momentarily stunned.

‘A place called Gorton Lane.’

His fingers began to tingle.

‘It’s behind the old cinema. You might need to look it up.’

He didn’t need to look it up. He knew Gorton Lane all right.

‘They’re going to give a statement at the scene … Adrian? Are you still there?’

‘Yeah, I’m here.’ Rain clouded the insides of his specs and his hair was dripping. He pushed it behind his ears. ‘That’s fine, Linda. I’ll go get Nige.’

‘I’m sending Kev to meet you there. Can you ask Nige to take general photos: cars, crowds, but at a respectful distance. The girl’s mum’s likely to be there, and we are not the Daily Star.’

She rang off.

Gorton Lane. Of all places.

Back in the pub, Nige was rolling another cigarette and staring contentedly into space.

‘Linda wants us to go to Toller Bridge,’ Adrian said, and told him why.

‘Blimey,’ Nige said, and downed his pint.

Gorton Lane was a cobbled street running alongside a section of the Rochdale canal in the middle of Toller Bridge. Today the cobbles were crowded with vehicles, including police cars. People gathered at the far end – a mix of police and locals, by the look of it. Adrian parked the Fiesta in the first spot he found, by the gable end of a terrace.

‘You could get a bit closer to the kerb,’ Nige muttered, readying his camera. 9

It was rich coming from Nige, who’d lost his licence for driving drunk. Adrian had started temping as an admin assistant at the Calder Valley Advertiser in November; when he passed his driving test in the February, just after his eighteenth birthday, Linda had quickly added photographer’s chauffeur to his list of duties. Since then he’d spent part of every day ferrying Nige about the local area to take snaps, but he often had his own tasks to perform as well. Today they’d been at a clothing outlet, so Nige could take snaps of some of the summer fashions. Adrian had taken down some details using standard questions and would type these up so one of the reporters could produce an article. The clothing place was paying for a double-page advert, so it was an important task and he took it seriously.

‘Should have reversed in, really,’ the photographer complained now.

Adrian bit his tongue. Besides, he had plenty of other stuff on his mind.

He got out of the car and stood on the cobbles, breathing in the cold air, smelling the faint, bready smell of the canal, and waited to feel … anything.

But apart from a sense of unease, there was nothing. Possibly because the street looked different to how he remembered it. Shorter. Narrower. And of course it was daytime now.

But he was still unsettled.

Act normal,he told himself.

Nige hurried across the road to take some wide-angle snaps while Adrian headed towards the crowd, curious in spite of himself to know what exactly had been found. The girl had lived only a few streets away from here, in a red-brick terraced house that was now familiar from TV news reports.

He passed a huddle of women, whispering to each other. 10Another woman joined them, saying loudly, ‘He’s gone and drowned the poor kid, hasn’t he? She’ll be lying at the bottom in the reeds.’

Adrian looked towards the half-hidden canal, its oily surface gleaming between the overgrown vegetation. He doubted there were many reeds growing in there.

‘What’s your business here, young man?’ an oldish policeman said, stepping in his way, frowning at his wet hair and, no doubt, Adrian’s youth.

‘Calder Valley Advertiser,’ Adrian said, holding out his press pass. ‘I’ve brought our photographer.’ He cleared his throat. ‘Who’s in charge, please?’

‘That would be DCI Struthers.’

Adrian followed the man’s gaze and recognised the detective from the TV news, with his peak of red hair and blue raincoat, busy talking to a group of locals.

‘Thanks,’ Adrian said, moving to loiter discreetly at the edge of the crowd, from where he could watch proceedings. He had a talent for going unnoticed, being short, a bit unkempt with his longish hair, and bookish in his square specs. To many people he was ‘just some kid’ and generally no one paid him much attention – which suited him fine.

‘Awright, Gaydrian!’ cried a familiar voice, merry as anything. ‘New coat? Leprechaun green, eh?’

He glanced down at the green jacket. It had cost thirty quid in the Corn Exchange in Leeds.

‘Tosser,’ he muttered, and Kev cackled, drawing appalled looks from two women standing nearby.

Kev Simpson was the newspaper’s trainee reporter. He was three years older than Adrian and had his sights set on a career with one of the tabloids. He was skinny and lithe, with 11bristly dark ginger hair and a narrow face. He made no secret of his opinion that he was wasting his time training at a local rag, writing up committee meetings and village fêtes. For the past twelve days Kev’s glee at eleven-year-old Sarah Barrett’s disappearance had stunk out the newsroom like a fart. Linda had lost her temper with him more than once.

‘DCI Struthers is in charge,’ Adrian told him.

‘Already spoke to him,’ Kev said smartly. ‘Early bird, an’ all that. Where’s Nige?’

Adrian nodded to where Nige was taking photos further along the road.

‘Nige!’ Kev yelled, waving. ‘All right, fella?’

‘Linda said not to intrude,’ Adrian hissed.

‘Bollocks to Linda. Oh, oh – look who’s here.’ He nodded towards a blue sports car that had just parked. ‘Only the flaming Queen of Sheba.’

A stout woman with a silver-blonde bob and a fuzzy dark blue shawl over her shoulders was easing herself out of the car. Adrian recognised her at once and a sense of dread made his muscles lock round his bones. He felt faint. Panicky too. Mouth dry, he glanced along Gorton Lane to the police cordon at the main road, beside the old cinema, and tried to think of an excuse to get away.

‘So she wants in on the act, does she?’ Kev said. ‘Always has to make it about herself. Look at her – all simpering smiles for the community.’ He barked out a laugh.

The woman was Sheila Hargreaves, familiar to Adrian, and to everyone else it seemed, as the anchor of Yorkshire Tonight, Yorkshire TV’s magazine programme, broadcast on weeknights apart from Wednesdays. Soft and motherly in appearance and demeanour, she was often called ‘Yorkshire’s auntie’. She had 12a reputation for laying it on thick with her emotional style of interviewing.

Adrian had met her once, years ago, and he didn’t want to see her again – now or any time. Unlikely though it was that she’d recognise him, he turned and stepped in behind Kev.

Sheila took herself in the direction of DCI Struthers. People watched, excitedly craning their necks.

‘Good afternoon, everybody,’ she said, sparing sad-but-warm smiles for the observers.

‘Was it Sarah Barrett’s clothes?’ Adrian asked Kev quietly once she’d passed by.

‘Sounds like it.’ Kev licked his lips. ‘Some lad found them draped on the brambles over there, plain as day. A jacket, a top and some jeans. Realised what he was looking at and told his mum and dad. I’d like to get the lad’s name.’

Along the lane Sheila Hargreaves had finished speaking to Struthers and was returning their way, sad-eyed and pensive.

‘How’s tricks, Sheila?’ Kev bellowed to her, making Adrian shrink miserably back so he was almost touching the nearest gable end.

She stopped and turned. ‘Ah, Kevin,’ she said distastefully. ‘And how are you?’

The two had had a run-in, Adrian recalled, when Sheila was opening a village fête and Kev was there to write about it for the paper.

‘Surprised to see you here,’ Kev said. ‘Thought you were all celebrity memoirs and cooking demos these days.’

She came close, her bright green eyes blazing. Not so soft and motherly now. Adrian sensed the crowd watching them. ‘I am here to meet Sarah’s mother Irene,’ Sheila told Kev quietly. ‘To do what I can to help.’ 13

‘Mother Teresa in person, eh?’ Kev said, with a snort.

Adrian held onto the cold brick behind him and willed himself to become invisible.

‘Might I suggest, Kevin,’ Sheila whispered tersely, ‘that if you can’t say anything pleasant or sympathetic, then you’ve no business being here.’

‘Steady on, Sheila,’ Kev said, miffed.

And then she spotted Adrian.

‘Have we met?’ she said, peering close.

‘I’m—I’m just the driver,’ Adrian stammered.

‘And your name …?’

She flashed her familiar smile, all antagonism gone. But there was an avid interest in her shrewd emerald eyes. Kev was observing his reaction curiously.

‘Adrian,’ he managed.

‘Adrian?’ Her eyes narrowed. ‘Right. Yes …’

She’d recognised him all right, but looked as if she couldn’t place him. ‘Well, it’s very nice to meet you, Adrian.’ Less pleasantly she added, ‘Goodbye, Kevin.’

Her gaze lingered on Adrian, then she stepped away and began to talk to a group of women standing nearby.

‘’Sup with you?’ Kev demanded when they were alone. ‘Star-struck or summat?’

‘No!’ He felt himself redden.

‘Sheila’s a has-been,’ Kev snorted. ‘Except she’s the only one who hasn’t realised it.’

A new murmuring from the onlookers. Heads turned. A female police officer was coming carefully along the cobbles, guiding another woman gently by the arm. There was no mistaking the skeletal figure of Irene Barrett. Her face had been all over the TV news for the past week and a half. She looked 14scared to death. She was sallow with big dark eyes.

Sheila Hargreaves swept over the cobbles to meet her and snatched up Irene Barrett’s unoffered hand in both of hers. Suddenly she was embracing the woman, and the two of them were crying.

Nige appeared at Kev and Adrian’s side.

‘Go for it, Nige,’ Kev ordered quietly.

Nige looked embarrassed, but pointed his camera and began to snap away.

Sheila Hargreaves and the policewoman led Irene Barrett to meet DCI Struthers. Adrian stayed put while Kev trailed after them, listening out for quotes that Linda would never let him use.

Adrian felt sick. This was a circus. He took himself back to the car to wait for Nige. He didn’t get in, but stood outside and smoked the last of his menthol cigarettes.

A crowd of onlookers had gathered behind the police cordon at the end of Gorton Lane. People stood grimly silent, eyes on the police activity. But one of them, an old woman with curly dyed-black hair, seemed much more interested in Adrian than in everything else that was going on. She eyed him intently, her lips moving as if speaking a curse.

He turned his back and finished his cigarette.

2

He told Kev he had a migraine and asked him to give Nige a lift back to the newspaper office, saying he’d collect the Fiesta from Gorton Lane later.

‘You better be at Barry’s thing later,’ Kev warned him, car keys in hand.

‘I’ll do my best.’

‘I mean it, Gay-boy. I need someone to take the piss out of.’

Barry Tillotson, the deputy foreman of the printworks, was a racist, pot-bellied pig of a man, and Adrian had no intention of going to his retirement do at the Irish Club.

Excuses made, he hurried in the direction of Toller Bridge’s main street and phoned his pal Gav from a call box, and an hour later they were in the King’s Head. Gav was a connoisseur of old man’s pubs and this was his choice. They weren’t the pub’s typical clientele – Adrian resembling a grungy student, Gav strikingly gothic with his Russian trench coat, backcombed black hair and eyeliner – but no one bothered them. 16

‘Decision’s made,’ Gav said, lighting a roll-up then picking tobacco off his lower lip. ‘I’m gonna leave Sunderland. I hate my course. Hate my course mates. Really fucking hate the people in my halls. I told my mums when I got back last night.’

‘Right. What did they say?’

Gav shrugged and beamed. ‘That it’s my choice and they’ll support me. I’ll apply to start at Leeds in autumn. You and me can rent together.’

Gav beamed and clinked his pint of Guinness against Adrian’s glass of Coke.

Nearly all Adrian’s school friends had gone to university the previous autumn, leaving him at home to resit the two A-Levels he’d messed up while his mum was ill. He missed his pals, Gav most of all. Gav was Adrian’s only friend from school who knew he was gay, though he still struggled to understand Adrian’s home life. But then their lives were very different. Gav had grown up with two mums in Hebden Bridge, the lesbian epicentre of Britain. His home was a place of acceptance and empathy. It was ironic that Gav was as straight as they came, while Adrian found himself gay and having to hide it. His mum, he suspected, would be fine after she got over the shock. His dad, less so.

But he was resigned to his situation, focusing on his future away from home, away from High Calder. Away from his past.

And things were coming together. He was on track for better grades and a place at Leeds University starting in the autumn. He imagined himself and Gav sharing a house. One of the shabby red-brick terraces around Hyde Park. Leeds would suit Gav. It was bigger, with a thriving goth scene. No one in Leeds batted an eyelid at eyebrow piercings or dyed hair on a man – even make-up. The thought of living there with his pal 17conjured up an idyll of freedom; a complete displacement from stress and shame. He found himself unexpectedly welling up.

‘You OK, man?’ Gav said, eyeing him.

‘Yeah.’

Gav drew him into a patchouli-smelling embrace.

Pulling away, Adrian wiped his face on his sleeve.

‘Here,’ Gav said, and pushed a rollie across the table.

He lit it inexpertly, inflaming half the cigarette and having to blow it out, making them both laugh.

‘They think it’s him, then?’ Gav asked. ‘The Lollipop Man?’

‘Linda does. And Kev’s in his element, the wanker.’

‘After all this time? How long has it been?’

‘Seven years, four months.’

Gav eyed him. ‘Sorry. Guess I should know that.’

‘Why should you?’ Adrian said. ‘It’s my business, isn’t it? I’d love it if everyone else forgot.’

Gav drank some of his pint.

‘Why would he start again? I mean, where’s he been?’

‘Fuck knows.’ He sank deeper into the soft leather of the bench and shut his eyes. He’d lied when he told Kev he had a headache, but now one was starting, high in his shoulders and neck.

Just over eight years ago, Samantha Joseph, age eleven, had gone missing from Halifax, four miles from here. Four months later, in the July, ten-year-old Jenny Parker vanished from Wyke, near Bradford. This time there were two witnesses, who had seen Jenny being walked across a road by a man they assumed was a lollipop man. He’d worn a white coat and carried the familiar ‘Stop – Children’ sign that resembled a giant lollipop. Then, in the October, eleven-year-old Paula Sykes vanished in a suburb of High Calder. None of the children were seen again, though 18items of clothing identified as theirs were found near the places they’d vanished from within a couple of weeks, stained with blood. Then in the December, a fourth child was taken, a boy this time – Matthew Spivey, age ten. He was taken away in a van from behind the old cinema at the end of Gorton Lane in Toller Bridge – but released after two hours. No one knew why he’d been let go, certainly not the boy. After that there were no more kidnappings. Just three families left with their grief and communities left with their fear. And a fourth family left traumatised but mostly ignored.

Now, just over seven years later, eleven-year-old Sarah Barrett had gone missing and items of her clothing had been found – at Gorton Lane.

It was only a matter of time before the community, the police and the media ran to ground the boy who’d spent time in the Lollipop Man’s company and might recognise him again: for instance, the crime reporter-turned-TV-presenter who’d interviewed the boy at the time.

‘The truth is, I don’t remember a lot about it,’ Adrian said. ‘I didn’t remember much at the time. They said it was shock. I tried to give them a description, but the photofit looked like Mr Potato Head.’

‘So let them ask,’ Gav said, blowing smoke. ‘Tell them you’re sorry but you can’t help.’

Adrian looked at his hands.

‘What?’ Gav demanded.

‘It’s best no one knows.’

‘Best for who?’

‘For me. For my mum and dad.’

Gav nodded but looked unconvinced.

‘My mum’s in pieces every time she hears Sarah Barrett’s 19name on the news. And my dad …’

Gav watched him, as if sensing more was coming.

‘He didn’t cope at the time,’ Adrian said quietly, making Gav frown. ‘It’s best if … it’s best if I just keep out of it. And hopefully no one will make the connection – after all, I’ve got a different name now.’

He checked his watch. ‘I’d better go. Walk with me back to the car and I’ll drop you at the station.’

3

Sheila Hargreaves emerged from Irene Barrett’s overheated terraced house to find a small group of women huddled on the pavement outside. They’d been chattering away in low voices but clammed up when they saw her.

‘Good afternoon,’ she said, managing a smile but avoiding eye contact.

‘How’s Irene, Sheila?’ one of the women called to her.

‘She’s very brave.’ She turned quickly away to hurry down the hill towards Gorton Lane where she’d left her car.

She heard the excited chattering pick up again in her wake and felt a wave of anger. The vultures pretended concern, perhaps even told themselves they had Irene’s best interests at heart, but in reality, this was a feeding frenzy.

Sheila had been a crime reporter at one time, and considered herself battle-hardened, but the encounter with the missing girl’s mother had shaken her badly. Sitting in the tiny living room, dark because of the closed blinds, she’d felt as if she was in the 21presence of an almost malignant misery. She’d spoken words of support and comfort, all the time wanting nothing more than to escape the room, the house, and get away.

But running away wasn’t the answer. She had to do something. To stop this if she could.

Gorton Lane was still busy with police and onlookers. She felt eyes watching her and heard excited whispers as she passed. She wondered if anyone would have the gall to request a signed photograph – and what she might say to them if they did.

She looked for Malcolm Struthers but didn’t see him.

‘DCI Struthers left ten minutes ago,’ a young, male uniformed officer told her.

‘That’s quite all right,’ she told him. ‘I have his number.’

Back in the car she opened her address book and dialled on her mobile phone.

‘Malcolm, it’s me, Sheila. Is now a good time?’

‘Hello, Sheila.’ He sounded weary. ‘Finished with Irene Barrett, have you?’

‘I’ve just left her place. That poor woman. She’s haunted. We have to do something to help her, Malcolm. What I mean to say is, I’ll help you. I’ll help you catch him.’

‘Will you, now?’

She hunkered down in the low seat of her MG, eyes scanning the bleak lane, taking in the little groups of people here and there, the blue-and-white tape flickering over by the canal.

‘It is him again, isn’t it?’ she said. ‘It is the Lollipop Man?’

‘We don’t know that yet.’

‘Oh, come on, that’s what everybody’s saying.’

‘I thought you’d given up the investigative stuff,’ he said. ‘You’re all local worthies and phone-in competitions now, aren’t you?’ 22

‘You’re right,’ she said. She shifted uncomfortably in her seat. ‘I want to help, that’s all.’

‘Really? You’re a journalist at heart, Sheila. I suppose you were grilling poor Irene Barrett for a story.’

‘I wasn’t, actually.’ She took a breath, already anticipating his reaction, and admitted, ‘I asked her to come on the show tomorrow night.’

‘You did what?’

‘She said yes.’

‘Sheila—’

‘It’s a free country, Malcolm. She’s within her rights. She wants to make an appeal directly to my viewers. I have a platform, so let’s use it!’

She could hear him breathing fast and shallow, enraged no doubt.

‘Four nights a week I talk to an audience of nearly half a million people across this county – they listen to me. They trust me.’

‘And what if Irene Barrett decides to trust you instead of us? What if she tells you something that doesn’t seem significant but which one of my officers is trained to spot? An anomaly. You’re right that I can’t stop her, but I’ll be talking to her and making a very strong case to keep out of the public view and to talk only to us.’

‘Right.’ She heard a tremor in her voice and saw Irene Barrett’s face again, wet and blotchy, her eyes like dark holes: wells down to an underworld of horror. ‘And what about her little girl?’

‘What’s this all about, Sheila?’ Malcolm said. ‘You’re acting like the angel of bloody mercy—’

‘You think this is about my ego?’ Her voice was calm again, thank God. Cold. ‘I’m part of this community, too, remember. I 23don’t ever want to live through anything like that again.’

‘No. Of course not.’ He sounded sheepish. ‘I’m sorry, love.’

He thought he’d upset her because he’d questioned her motives. Her integrity. He hadn’t. He’d called her out for playing an angel of mercy, and thus reminded her, unknowingly, of a time she’d been the exact opposite. She could tell him about it. But he would no doubt tell her to get over it, not to make mountains out of molehills, and she didn’t think she could bear it.

‘It is the Lollipop Man, isn’t it? It must be. The way he left the clothes …’

‘We’re not ruling anything out,’ he said. ‘We’re not ruling anything in, either.’

‘The very idea that it could happen all over again … Let me help you, Malcolm. Surely there’s a better chance of catching him this time. Think about it. He took three children in the space of six months, then nothing else for more than seven years? Why the gap? I know there were theories at the time and afterwards: did he get frightened and go to ground? Did he move away? Did he get sent to prison for something else? You could check, couldn’t you?’

‘We looked at all of that when he went quiet. A case like this is never truly cold, especially when the bodies are still undiscovered. Even so …’

She listened hard to the silence down the line.

‘There’s something you’re not telling me, isn’t there, Malcolm?’

He took his time, then said, ‘It’s not clear-cut.’

‘Oh?’

‘Sheila, I’m busy right now,’ he said. ‘Tell me when you’re home and I’ll pop by.’

4

‘Awright, Gay-boy,’ Kev called when Adrian returned to the newsroom in the centre of High Calder, four miles from Toller Bridge. ‘Got over your brush with fame?’

‘Piss off.’ Adrian slung his bag onto the back of his chair at the corner desk.

‘Language, please!’ Linda said, making him jump. The editor was on her way back from the little kitchen, coffee in hand.

‘Sorry,’ he muttered, feeling himself redden while Kev chuckled.

‘Adrian, can I have a word?’ Linda said, tone kinder now. ‘It’ll only take five minutes.’

He followed her meekly into her office overlooking the market square, then sat and waited while Linda readied herself. She looked tired and harassed. She wasn’t forty yet, but looked like she’d had a hard life. Kev said it was because her kids were bastards. The oldest of the three was always in trouble and Linda was forever being called in to see the school. 25

‘Kevin told me what happened,’ Linda said. She leant over her desk. ‘Are you all right?’

He stared and felt a flutter of panic in his chest. ‘Yeah. Yeah. I’m fine. What did … What did Kev say?’

‘That you got a bit upset.’

He groaned to himself and balled his fists in his lap.

‘I should have thought before I asked you to take Nige there,’ Linda went on. ‘It’s a horrible thing. How are you feeling now?’

‘I’m fine. Honest!’

‘You told him you had a headache. Maybe you just needed some time.’

‘I did have a headache,’ he said, avoiding her peering gaze. ‘That’s why I said it. I had a headache so I went to Boots.’

She gave a little nod and a half-smile, as if happy to play along with the fiction.

‘Can I go?’

‘Of course.’

He got up.

‘Oh, and I nearly forgot,’ Linda said. ‘Your mum called. She wants you to ring her at work.’

‘Right.’ He took a deep breath. ‘Thanks.’

‘She called twice. It sounded important.’

Back in the main office, Kev was on the phone. ‘Nice one, mate,’ he said and hung up, then leant back in his chair so that it creaked. ‘Good news, Gay-boy: Barry and the lads are finishing at four and heading out for beers. Get tanked up for tonight. You know what that means. We’ll be knocking off early.’

‘I have to go into college,’ Adrian said.

‘Youhave to go to fucking college?’ 26

‘I’m getting an essay back—’

‘And that’ll take, what, about twenty minutes?’

‘It’s important!’

‘You’re not gonna come. I knew it!’

‘I’ll come for a couple.’

‘Jonno’s booked a stripper,’ Kev said now. ‘He’s asked for Big Tina.’

‘That’s a disgrace,’ Linda said, appearing in her doorway.

‘Not your party, Linda, love.’

‘Leave him alone, Kev,’ Linda said.

‘Well, if college is tonight you can come for a few at the Bridge at four.’

‘I’ll see.’

Adrian typed up the shorthand notes he’d taken at the clothing outlet in Halifax. He didn’t need shorthand in his admin role, but he’d shown an interest so Yvonne, Linda’s deputy, had begun teaching him. His notes weren’t perfect but he managed to decipher them, then went downstairs to the little meeting room and rang his mum at the carer’s agency she managed in Huddersfield. She answered quickly, then fired off questions about his welfare and when he’d be home.

‘Mum, I’m fine.’

‘It’s all over the news,’ she said in a rush, her voice rising with stress. ‘It’s him again, that’s what everyone’s saying. He’s taken this little girl and – oh, God, her poor mother!’

She was sobbing now. He held on to the receiver and closed his eyes.

‘They don’t know anything for sure,’ he tried uselessly.

‘Of course it’s him!’ Cross now. ‘And her mother will never see her again.’

He did his best to mollify her, then reminded her he had 27a work do tonight, so would be late home. It was a lie, but a white one. To reassure, not deceive.

‘I need to go, Mum,’ he said. ‘Try not to worry.’

He was crossing the cobbled market square, heading for the bus station, when he realised he was being watched from under one of the arches.

It was the stocky old woman he’d seen at the end of Gorton Lane, the one with the jet-black perm. She was eyeing him beadily, her lips working away.

He hunched his shoulders and hurried on, only to hear quick footsteps behind him.

‘Oi, you,’ she growled. ‘Wait!’

He turned and stared as she approached. She was shorter than him and peered up, nodding in satisfaction to herself.

‘Adrian Brown, isn’t it? Don’t lie.’

‘Do I know you?’ he demanded, recoiling.

‘Thought it was you,’ she said, half to herself. ‘Said to myself when I seen you earlier, that’s him. Knew your name and remembered where I’d seen you. Nowt gets past me.’ She smiled unpleasantly.

She had an aggressive face, with a snub nose, heavy chin and small black eyes. She had a single gold earring and her tightly permed, dyed-black mullet combined with the leather jacket made her look like an old rocker.

‘Who are you?’ he said, heart racing.

‘Name’s Wormley,’ she said and hitched the strap of her big leather handbag higher onto her shoulder. ‘Edna Wormley. Reckon I get called all sorts besides.’

Wormley. Yes, he’d heard Linda and Yvonne complaining about her, with Kev chipping in the occasional rude remark. 28She was a troublemaker, he recalled, forever writing semi-literate letters to the Advertiser and ringing up, demanding to speak to Linda.

‘What do you want?’

‘Just a little chat.’ She smiled. He detected a meaty smell off her, possibly from the leather jacket.

‘I haven’t got time,’ he said. He turned to go.

‘Not so fast,’ she snapped, stepping in front of him with remarkable nimbleness. He made to go round her. ‘I know everything, young man. I know your name – your real name, I mean. And I know your mam’s called Margaret. Works at Hardaker’s in Huddersfield.’

He stopped and gawped at her, feeling as if the blood had left his face.

‘I’ve got something I thought youmight be interested in,’ she said.

He tried to appear nonchalant. He glanced about. The square wasn’t busy, but he might be seen – including by Kev from the office window behind him.

‘Then again, maybe you wouldn’t …’ she went on. ‘Might be wasting my time.’ Her voice hardened. ‘It’s about Sarah Barrett.’

Adrian was aware of a woman in a bright blue coat and holding an umbrella glancing his way as she passed. She looked vaguely familiar.

‘Not here,’ he hissed at the old woman. ‘Follow me.’

He led her into the shadows under one of the arches where there was a bench, though neither of them sat. Pigeons cooed unseen under the roof. The shelter smelt of their droppings.

‘What about Sarah Barrett?’ Adrian demanded now.

‘She’s with the angels now.’ Mrs Wormley smiled sadly through the gloom. 29

He could smell alcohol on her breath, its sweet sharpness mixed with the meaty smell from her jacket.

‘Is she?’

‘She is,’ she said, her voice breaking a little, ‘the poor mite.’ She pulled a tissue from her sleeve to wipe her nose. ‘And I know who took her,’ she added, her voice hard again.

His stomach churned. ‘Who?’

She narrowed her eyes.

‘Like to know, wouldn’t you?’

‘If you’re telling the truth.’

‘Don’t believe me? Oh, well, I’ve better things to be doing.’ She looked about her, as if about to take her leave.

‘If you know something about Sarah Barrett, you should tell the police,’ he said.

‘Talk to them buggers? Ha.’

‘Well, OK. Tell me, and I’ll talk to them.’

‘I want it on the front page of your newspaper,’ she said. ‘My picture with it. You can organise that, can’t you?’

‘I’m just the administrator. I could ask Linda. She’s the editor—’

‘I know who she is, lovey, and we don’t need her.’ As if in preparation for the anticipated photo shoot, she took a lipstick and compact mirror from a pocket in her jacket and touched up her lips. ‘You and me, Adrian Brown,’ she said when she was done, ‘we know what this is about. Folk think I’m mad.’ She tilted her head, eyeballing him. ‘I hear them. “There she goes, the old loony.”’ She chuckled. ‘Must think I’m deaf and all.’

She went on, making the case for how she, and only she, saw things for what they were. How all her life she’d exposed lies and been proven right, time after time.

‘They’ll say it on Judgment Day. They’ll say, “Here she 30is – Edna Wormley – she saw through them. She had it right.” That’s what they’ll say – the angels.’

She rambled on, mentioning John Major then Boris Yeltsin. Adrian recalled Kev saying she had an obsession with Russians.

‘Gorbachev,’ she said now. ‘He’s another one.’

He wondered if she’d ever get to the point and itched to check his watch.

‘Sitting there, horrible furniture, leather everywhere, grinning away. Her waiting on him, hand and foot. Gold teeth shining but dead inside—’

He didn’t know if she was now referring to Gorbachev, Yeltsin or someone else.

‘Anyway, it’s all in here,’ she said, appearing suddenly to come to the point and rooting in her bag.

He waited, muscles locked with tension, and was taken aback when she drew out a deck of playing cards. Big ones with red backs. She gave them a shuffle.

‘Choose one,’ she said, holding the fanned deck towards him. ‘Not scared, are you?’

He met her mocking gaze and took a card.

‘Don’t show me.’ She studied him. ‘It’s the Tower, bet you anything. Go on. Take a look.’

He did so, and the Tower it was. A cartoonish image of lightning striking a black spire, cracking it in two so that the top half had begun to topple. People in medieval garb tumbled from the crack, mouths open in horror.

‘Worst card in the deck,’ she said. ‘Knew you’d pick it. There’s shame and death hanging over you like a black shroud, Adrian Brown.’

He stared, speechless, as she grabbed the card off him and dropped it and the rest of the deck back into her bag. 31

‘Watch your step, young man,’ she said.

‘Look—’

‘Hold your horses,’ she snapped, then drew a long, dirty-looking envelope out of her bag. Slowly, like a magician. ‘Here it is.’

‘What is?’

‘Not as if he ever confessed, is it?’ she said, flapping the envelope about, taunting him. ‘I mean, he’s a bad one – always was – but he’s not a bloody idiot. Neither is she.’

He reached for the envelope.

‘Ah-ah! Hands off!’

She lifted the flap and teased out a single sheet of paper. A letter, with handwriting on both sides. Nice, curly, old-fashioned handwriting. Mrs Wormley took a pair of dirty-looking glasses from inside her jacket and set them on her nose.

‘Can I see?’ he said.

‘No, it’s mine!’ she snapped. ‘Is now, at any rate.’

She was playing him. Had been since the start, when she’d spoken his name in that snide way and mentioned his mum.

‘I don’t have time for games,’ he said, annoyed at himself for putting up with her for this long.

‘You’ve time for this,’ she said. ‘That little kiddie won’t be the last. Now, it’s time for you to make me a promise.’

‘A prom—’

‘I want to be on the front page. You with me – the boy who survived and the lady who worked it all out. And I want paying,’ she added with a smirk. ‘Don’t see why I should do all this for free.’

He felt suddenly ice-cold.

‘No,’ he said.

‘What?’ 32

‘I said, no. Take your letter to the police. I’m not doing this.’

He pushed past her and stalked out from under the archway, feeling immediate relief at putting distance between the two of them.

‘Idiot!’ she yelled after him.

5

‘The thing is, Sheila,’ Malcolm Struthers said, face to face across a kitchen table this time. ‘We’ve got a witness this time, too.’

‘A witness?’

They were in the vast modern kitchen of Sheila’s house, a converted barn just off the A-road that crossed Widdop Moor – about as high and remote as you could get in this part of the Pennines. He’d asked to come here for privacy, but said he couldn’t stay long. Alex, Sheila’s husband, was keeping out of the way, hunched over his gardening magazines in the living room, no doubt.

‘She’s a young girl, mid-teens. Sensible kind of kid.’

‘And?’ Sheila could hardly breathe.

‘It wasn’t the Lollipop Man,’ Malcolm said.

‘But how does she know? Appearances change—’

‘It was a woman, Sheila. A woman took Sarah.’

Sheila stared, horrified.

‘A thin woman with bleach-blonde hair,’ he said. 34

‘My God,’ she said after a moment, hands going to her mouth. ‘Oh, my God. Another Myra …’

‘Oh, don’t say that.’

‘That’s what the tabloids will say. No one ever suggested a woman was involved before.’

‘So now you understand my dilemma.’

No wonder he looked haunted. Exhausted, too. She’d noticed at Gorton Lane that there was a lot of grey in his copper hair. He was only a year or two her senior – not yet fifty – but he looked ready to drop.

She got up from the table and moved to the window, and gazed out across the paddock towards the black, looming moors under a pall of leaden clouds. The views from here were spectacular, but you could feel very exposed at times.

‘You can’t withhold this kind of information, Malcolm,’ she said, returning to the table. ‘People trust women, in spite of Hindley. Most children would trust a nice, friendly lady … You have to warn them. Warn the parents!’

‘We will. Tomorrow probably. We’re planning for a press conference in the afternoon.’

‘Come on my programme tomorrow evening, then,’ she said, quickly. Her producer wouldn’t like it, but Sheila could deal with that. ‘You can do your press conference in the afternoon, then a couple of hours later it’ll be you and me on the sofa. We can reassure people, but make sure they’re taking steps to keep their children safe. People are so innocent. So trusting. I was reading some of that book that was published a year or two after it happened. The one by Dee Thompson. There are things I’d forgotten.’

‘You might have forgotten them,’ Malcolm said. ‘I was a new sergeant. I worked on that investigation.’ 35

‘One of the things,’ she went on, ‘was that there were two sightings of the man who took the second girl, Jenny Parker. Two. And yet it led to nothing. How could that be? One witness was a retired police officer. He didn’t think anything of it at the time, because—’

‘Because the little girl was holding hands with a lollipop man, and she seemed happy as anything as they crossed the road.’

‘That’s right,’ she said. ‘The other witness actually knew Jenny. She was a primary school teacher and had taught her the year before. She sat there at the head of the line of traffic, and they crossed right in front of her.’

‘They didn’t see his face, only the uniform.’

‘But this was after 5 p.m. School crossings were all over by 3.45 p.m. Yet no one thought to question it.’

‘Innocent times.’

‘Naive times,’ she said. ‘Though God knows why, after Hindley and Brady a few miles up the road.’

‘Things changed fairly sharpish,’ Malcolm said. ‘Especially after the third girl was taken.’

‘I remember. They made genuine lollipop people wear ID badges. Then there were the vigilantes. Gangs of men walking the streets with baseball bats. There was nearly a fourth victim, as well, except the child got away.’

‘We didn’t count that attempt as part of the series,’ Malcolm said. ‘It was a boy. Also, the man didn’t wear a lollipop uniform – the lad thought he looked like an “ambulance man”. Anyway, it was a decision made by people more important than me – they didn’t want to count the boy,’ he said. ‘Sheila, the lad was lucky. The girls who disappeared are the ones who matter. They’re the ones who need justice.’

‘Come on the programme, Malcolm. At least think about it.’ 36

He watched her as she spoke, as if deciding whether to trust her.

She reached across the table for his hand, but he drew away and rose.

She saw him to the door and they said their goodbyes with nothing agreed, then she went to the fridge for a half-full bottle of Chardonnay. She filled a glass then took one mouthful before realising she didn’t want it.

‘Everything all right, darling?’

She looked up. Alex was standing slightly stooped in the kitchen doorway, his clothes crumpled and his grey hair tousled, as though he’d just woken up. His reading glasses were on top of his head, which meant he’d probably fallen asleep reading one of his gardening magazines.

‘Yes,’ she said stiffly, as though she’d been caught in the act. ‘Malcolm’s just left.’

‘Oh, yes,’ he mused, distractedly. ‘All right, is he?’ A yawn.

‘He’s … I think he’s struggling. It can’t be easy. Here, I poured this but I don’t want it.’ She held the glass out to him.

He came into the room and took it from her. He sniffed then tasted it dubiously. ‘The bottle’s been open a while,’ he murmured, putting the glass down on the counter. ‘What’s for dinner?’

‘Chicken casserole,’ she said. ‘I defrosted it. Shouldn’t take long.’

Alex retreated, sloth-like, to the living room. He’d be asleep again in minutes, she realised, suddenly irritated. Alex was often dopey at this time of day, but tonight his yawning distractedness seemed almost offensive.

For a few minutes she stood at the sink, deliberating. She’d told Malcolm she wanted to help by giving him a slot on her 37show. But she needed to do more than that. She needed to help stop this monster in his tracks. Him and the woman working with him. And she knew where to start: with the failed kidnap attempt. The boy who got away.

She went into her study, where Alex wouldn’t hear her, and lifted the phone.

‘Jeanette?’ she said. ‘It’s Sheila. Are you on duty tonight? Oh, good. Only, I need a favour.’

6

The Jester, like many gay pubs in Adrian’s experience, was in the seediest part of town, beyond the train station, down by the canal, surrounded by abandoned buildings. It sat right on the towpath, at the point where the water vanished into the mouth of a pitch-black tunnel.

He felt jumpy walking along the towpath, especially after dark, and started at the sound of a kicked stone behind him.

‘Hello?’ he called and peered into the shadows.

No answer. Only silence.

A high laugh from the direction of the pub. A group of older women stood about outside, holding pints, enjoying some joke or other. He hurried their way.

The pub was like a sanctuary, garish but cosy. The Jester may be Victorian, complete with leaded windows and wood panelling, but it was the opposite of quaint. Fairy lights framed the bar. Neon cardboard stars were stuck up behind, advertising special offers in black felt-tip: Bacardi double £1.50, Taboo £1. A 39dusty mirrorball turned over a dance floor – a square of grubby laminate next to the pool table – sending silver spots flying to the sounds of the jukebox. The landlady favoured seventies love songs: the Carpenters and anything Motown. If you wanted other music, you had to pay, feeding pound coins into the jukebox. Right now the speakers were blaring Ace of Base.

He spotted his pal Debbie in her usual corner, nursing a half-drunk pint of purple liquid.

‘Hiya. Do you want another one?’ he asked.

‘If you’re paying.’ Debbie beamed.

Debbie was unemployed and surviving on benefits. They’d been in the same year at school, but had never had a lot to do with each other. He’d left with nearly the right grades to go to the university of his choice, while she’d scraped a single E and left with no idea what to do next. Most of her time seemed to be taken up caring for her granddad, whom she’d lived with since her alcoholic mum booted her out a week after her seventeenth birthday. Adrian felt sorry for her. She didn’t take very good care of herself, smoking too much and existing on Pot Noodles, chips and fried chicken.

‘Everything all right?’ the landlady Bev said when he approached the bar.

‘Yeah, why?’ He knew he sounded defensive and gave her a smile.

She raised a sceptical eyebrow. ‘Look a bit harassed, that’s all. What’ll it be?’

‘Pint of Carlsberg and a pint of Snakebite and black, please. Oh, and two packets of Scampi Fries.’

He carried the drinks and crisps over to Debbie. His nerves had been on edge since the call to Gorton Lane and they’d worsened following the encounter with Mrs Wormley. Her 40claims to have knowledge about who had taken Sarah Barrett had preyed on his mind. At college, waiting his turn to talk to his tutor, he’d noted down everything he recalled her saying in his amateurish shorthand at the back of an A4 pad. He wasn’t sure what he could do with the information, but it seemed important to at least record it.

‘What’s up with you?’ Debbie said, eyeing him with a frown.

‘Nothing!’ he snapped and shrugged off his jacket. ‘Why does everyone keep asking me that?’ He saw her recoil at his tone. ‘Sorry. Been busy, that’s all. I was at college to get my essay mark just now.’

‘Oh? How did you do?’

‘OK.’

He’d got an A in his latest essay on King Lear and the tutor had written congratulatory remarks at the bottom, but he wasn’t about to tell Debbie, who’d be embarrassed about her own lack of achievement.

‘You’re so brainy,’ she said glumly.

‘I’m not. If I was I wouldn’t be doing resits.’

‘That wasn’t exactly your fault, though, was it.’

His last year at school had been a nightmare after his mum’s cancer diagnosis. His exam results weren’t good enough to get into Leeds by several points. He had offers of university places elsewhere, but he was fixed on studying English at Leeds. Two weeks after he got his results, his mum got the all-clear, and he signed up to retake two of his courses at night school.

‘If I was brainy then I could get away from here too,’ Debbie said.

‘Think positive,’ he said. ‘Decide what you want to do and go study for it, and don’t give up.’

‘But what about my granddad?’ 41

‘The council could send carers in,’ he said. ‘That’s what my mum’s agency’s for.’

She looked gloomily into her purple pint, then took a sip. ‘Ta for this.’

‘Is Elaine in tonight?’ he asked her now, to cheer her up.

‘Starts at eight.’ A small smile.

‘Any progress?’

‘Maybe.’ The smile became a grin.

Debbie had formed an attachment to Elaine, who worked a few hours a week behind the bar. Elaine was training to be a paramedic, and was the reason Debbie spent so much time in the pub – and why she was taking more care of her appearance lately, washing and straightening her hair, even wearing make-up.

‘Hiya,’ a voice said, and Debbie’s pal Little Phil landed on a stool beside them.

‘I thought you’d left,’ Debbie said to him.

‘Nowhere to go to,’ Little Phil said, then turned a winsome smile on Adrian. ‘And then I heard Adey was here.’

Little Phil had a crush on Adrian and didn’t try to hide the fact. He had bleach-blond hair and piercings in his ears, nose and bottom lip. He lived in a hostel for care leavers and augmented his dole money by selling all manner of knock-off goods here at the pub, from cigarettes to CDs – to which Bev turned a blind eye.

The music on the jukebox changed to Haddaway’s ‘What Is Love?’.

‘Rozzers were in earlier,’ Little Phil told Adrian.

‘The rozzers?’ The police rarely came anywhere near the Jester. ‘What did they want?’

‘To put up a poster of that missing kid,’ Debbie said. ‘It’s on the board.’ 42

Adrian craned his neck to look at the noticeboard by the bar. It was drawing-pinned among the posters advertising a pop trivia quiz and Demi’s Dragalicious Karaoke Night, and the one he’d pinned up for his mum’s agency. The poster showed Sarah Barrett in her school uniform grinning for the camera.

‘Horrible, isn’t it?’ Debbie said.

‘I saw her mum today,’ Adrian said, chest tightening uncomfortably at the memory. ‘I had to take Nige to where they found her coat.’

‘Do you think she’s dead?’ Little Phil asked him.

‘Yeah, of course.’ They fell into a gloomy silence.

Mrs Wormley had thought so. What had she said – that Sarah was ‘with the angels now’? Something morbid like that.

Debbie said, ‘Do you remember when those kids went missing before?’

‘Kind of,’ he said, employing his usual strategy of vague evasion. Neither Debbie nor Little Phil had any idea what had happened to him.

‘The Lollipop Man,’ Debbie said. ‘What if it’s him again, Adey?’

As if on cue to distract her, the pub door opened and Elaine came in for her shift. She shrugged off her leather jacket and gave the two of them a little nod.

‘Hiya,’ waved Debbie, all girly now.

Elaine was in her early twenties, slim and boyish with short fair hair. She nodded a hello to Adrian, then headed behind the bar, where she fell into hushed conversation with Bev. Debbie stared after her, transfixed.

The women who’d been drinking outside had come in and bagged a table. The place grew steadily busier but at last Elaine came over. She picked up Debbie’s finished glass and the two 43empty crisp packets.

‘Careful when you’re walking home,’ Elaine said, her grey eyes wide and wary.

‘What makes you think I’m going anywhere?’ Debbie said.

‘What do you mean?’ Adrian asked Elaine.

‘Some creep along the towpath just now,’ Elaine said, ‘hanging about in the shadows.’

‘Whereabouts?’ Adrian asked, feeling the blood leave his face as he recalled that skittering sound.

‘Near the steps. Under one of the archways. I told Bev.’ She glanced over at the bar, where Bev was busy pulling a pint. ‘She said not to call the police in case it puts the punters off.’

‘Druggy?’ Little Phil asked.

‘Dunno.’

‘Everyone’s so jumpy,’ Debbie said to Adrian when Elaine had gone back to the bar.

‘Yeah, they are,’ he said quietly.

‘Adey …? Are you sure you’re all right?’

‘Yeah, ’course! I’m gonna get another drink. Do you two want anything?’

As often happened, he stayed in the pub longer than he meant to. By ten he’d drunk five pints and his head was spinning.

‘Might ring Ste,’ he said to Debbie now Little Phil had left them.

She raised an amused eyebrow. ‘On a school night?’

He rang Ste’s house from the payphone at the bar, a finger in his other ear to deaden the sound of the music. Ste’s mum answered. ‘Do you know what time it is, young man?’ she demanded. Ste came on the line, sounding shifty and gruff as he always did when Adrian called. 44

‘Wondered what you were up to,’ Adrian yelled over the noise in the pub.

‘Not a lot. Might watch a movie with some beers. Wanna come over?’

‘Might do,’ Adrian said.

Lads. Making a lads’ arrangement. Ste’s mum never suspected a thing.

Leaving the pub, he tripped and fell into the door frame.

‘Steady,’ a woman by the door said, frowning with mock disapproval at his drunkenness.

On the towpath it was dark now and half the streetlights were out. The ravine between the buildings was full of shadows. He sprang along, singing merrily, having quite forgotten Elaine’s warning. If he was quick he could get a bus just after half ten from outside the station that went up to Ste’s fancy housing estate. By ten to eleven he’d be up in Ste’s attic room – lads hanging out in a lad’s bedroom. They’d play their wordless, encircling game, choosing a place to sit, maybe the two of them on Ste’s bed, maybe on Ste’s floor, edging steadily closer until their arms or feet touched … And then, inevitably, Adrian would be yanking open Ste’s belt buckle, or pulling at the elastic waist of his tracksuit bottoms, while Ste lay there, nonchalant, eyes still on the TV, as if nothing unusual was happening. Adrian put his hands in his pockets to disguise the bulge in his jeans, not that there was anyone around to—