5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

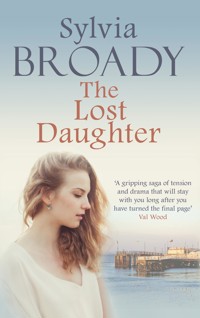

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

1930, Hull, East Yorkshire. Alice Goddard is fleeing through a rain lashed street from her violent, bullying husband Ted and fearing for her life and that of her two-year-old daughter Daisy. Running to the police station for help, she becomes involved in a road accident. Seriously injured, she lies in a coma in hospital. When she recovers, Ted has disappeared and Daisy is missing...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 530

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

The Lost Daughter

SYLVIA BROADY

To the air ambulance nurses of the WAAF who have inspired me to write this book. I wish to thank them for their service

Contents

Chapter One

Hull, East Yorkshire, 1930

The rain lashed at her face and body, her thin cotton nightdress clinging to her bare legs, her shoeless feet hitting the hard pavement, but she didn’t stop running. Fear gripped her heart, and every bone and muscle in her body. Terrified, she glanced over her shoulder, seeing a dark shadow looming. Was it him? Panicking, she ran faster, the pain in her chest almost at bursting point. She could still see his dark, evil face as he lunged at her. Ahead, she could see the faint glow of a light: the police station. Help me! Help me! Save my little girl, my little girl! The words reverberated in her head.

Stepping out into the road, she stretched out her arms to propel herself even faster. Then screeching and skidding noises on wet surface and the sound of screaming filled her whole body and mind. The impact, the pressure of metal against her thin body sent her up into space. She felt herself flying over the cold, sodden street. And then the silence of oblivion swallowed the pain and terror of her anguished body.

The man in the black saloon car slammed on his brakes. ‘Bloody hell!’ he yelled, his voice juddering with shock.

The duty policeman hurried from the station. ‘What’s happened?’ he asked.

‘I didn’t stand a chance!’ the driver wailed. Both men stood staring down at the still body of the young woman.

‘Is she a gonner?’ someone asked.

A middle-aged woman knelt down by the side of the young woman and took off her coat, placing it over the cold, wet figure. She shouted at the useless men. ‘She has a pulse. Get an ambulance – quick!’

The woman’s voice galvanised the men into action.

‘Who is she?’ asked the policeman.

They shook their heads and mumbled, ‘Don’t know.’ No one seemed to know who the young woman was.

No one took any notice of the big man, well wrapped up in his jacket, muffle and flat cap, standing on the edge of the gathered crowd, surveying the scene and listening to what was being said. Then he silently slipped away.

Back at the house in Dagger Lane, the man quickly wiped up the blood and set the furniture right. Going upstairs to the bedroom where the little girl was sleeping, he stood for a few moments just watching the gentle rhythm of her breathing. He felt nothing for her. She was just a kid, a damned nuisance as far as he was concerned, and she had no place in his life. He needed to get rid of her. Going downstairs, he sat on a chair and rolled a cigarette, lit it and drew heavily, contemplating what to do next. With any luck, his useless bitch of a wife would die. He didn’t want to be tied down to a woman and a bairn; his biggest mistake was marrying her. He liked his freedom and to have any woman he fancied.

He must have dozed off for the next thing he knew was the kid bawling its head off, crying for her mammy. ‘Shut your bleeding noise,’ he bellowed up the stairs.

‘I want a wee-wee,’ the little girl cried.

He was just about to race up the stairs to shake the living daylights out of her, when he stopped. An idea just dropped into the lump in his head he called a brain.

He galloped up the stairs to the little girl’s bedroom.

‘Mammy,’ she sobbed. Her tiny, convulsed body shrank away from the big man.

‘Shurrup and stop moaning.’ He snatched her up from the wet, sodden bed, clumsily wrapped her in a blanket, and clattered downstairs and out into the street.

‘Everything all right?’ asked the next-door neighbour. She’d heard the banging, clashing and shouting last night and the bairn crying for her mammy this morning.

The big man was just about to give the nosy neighbour a mouthful of abuse when he stopped and thought, and then said, ‘It’s the bloody missus, she’s gone off with another bloke and left me and the bairn to fend for ourselves. I’ve ter work so I’m tekkin’ bairn round to her granny’s.’ That’ll give the bloody old hag something to gossip about, he thought, as he hurried down the street, avoiding going near to the police station.

The child, frightened in the big man’s huge arms, shut her eyes tightly, put her thumb in her mouth and sucked.

Arriving at his wife’s mother’s house in Marvel Court off Fretters Lane, the big man rushed in without knocking. Four bairns were sitting round the kitchen table eating a basin of watery porridge each. Wordlessly, they all stared at him. Their mother, Aggie, who was in the scullery washing the pan used for the porridge, spun round at the sound of heavy feet crashing into her kitchen.

‘Ted, what’s up?’ She was surprised to see her son-in-law for he rarely visited − he wouldn’t have been her choice for her daughter to marry. He was too rough and full of himself – she might be poor, but she had standards. Then she noticed the bairn in his arms.

At the sound of her granny’s voice, the little girl began to cry. ‘Mammy,’ she hiccupped.

Ted thrust the child into the startled woman’s arms. The lies came easy to him. ‘Your bloody daughter’s upped and left me for another bloke, and I’m off ter work, so you look after the brat.’ With those words, he turned and stalked from the house.

Aggie fell onto her chair by the kitchen fire, holding the wet bundle. The little girl, arms locked around her neck, sobbing onto her bosom.

Finally, getting over the shock, Aggie unfastened the tight arms from her neck and, with an edge of her pinafore, she wiped away the snot from her granddaughter’s nose. Then she rocked her gently until her sobbing ceased.

All the time, her children went about their daily routine, not speaking a word, not wanting the wrath of their mother’s tongue or a smack across their ears. Their breakfast finished, the three boys went off to school and the girl to work in a shop.

Feeling annoyed at being left with the care of her granddaughter, Aggie discarded the little girl’s sodden nightdress and bathed her in tepid water in a bowl in the scullery stone sink. She found a vest, knickers and a dress, all old and tatty. ‘They’ll ’ave ter do for now,’ she muttered. One thing was for sure, she wasn’t going to have the bairn shoved on her. No! She had her whack of looking after her own bairns with no help from anyone. Come tonight, she’d take the bairn back to Ted and let him sort out her care.

She glanced at the clock on the mantelpiece. It was a wedding present from her father and it reminded her of happier times. That was all she had left: memories of when she was a young married woman with high hopes until the Great War changed everything. Her Albert came home a broken man, only good for bedding her, and then he died, leaving her with seven children and another on the way. She lost three of the bairns to diphtheria. Life became a brutal, harsh struggle with poverty and hunger, a never-ending daily toil to survive, and she was still doing it – struggling! She couldn’t cope with another bairn, not at her age. Besides, she had advertised for a paying lodger and a middle-aged man who worked at the flour mill was coming in a fortnight. That would give her chance to buy a second-hand bed and turn her front room downstairs into a bed-cum-sitting room. She’d given up the pointless idea of having the front room to be used only on special occasions. What occasions did she have, anyway?

‘Time I was going to work,’ she said to the little girl who sat on the floor, her eyes brimming with tears.

Aggie had two daily cleaning jobs, one during the day at a big house on Baker Street and the other one was in the evening, cleaning offices down Bowlalley Lane. There was no way she could take the bairn with her to either job, and she wouldn’t leave her in the house on her own, so she carried her to a neighbour’s house. ‘I just can’t understand our Alice leaving her bairn. She is so devoted to her,’ she said to the old widow, Mrs Yapham.

Mrs Yapham, who liked to sit at the window to pass her days and to earn a bit of money by keeping an eye on working mothers’ children, tutted and said, ‘Bring me a packet of ciggies back with yer.’

‘I suppose,’ Aggie replied, grudgingly. She’d make sure she got the money back off that lout, Ted. ‘It’s a right mess,’ she said. ‘Men are so bloody useless. They’ve no idea about bairns. Our Alice hasn’t got the sense she was born with buggering off with another man. Though I can’t believe she’d leave her bairn behind. It’s not like her.’

Later on, when Aggie had given her children their tea of bread and dripping, she bundled the little girl, Daisy, up in a blanket and, taking her daughter Martha with her, set off to see Ted. As they trundled along, Aggie was getting fraught and Martha was now carrying a scared bairn who hid her face in the blanket.

‘Bloody men,’ Aggie muttered under her breath. She felt too old and exhausted to have to be looking after another bairn.

Martha kept quiet. All she thought about these days was how soon she could escape her mother’s grasp. And she certainly wasn’t going to marry a fellow and be a drudge and have too many bairns to look after. No. For the past few months she’d been working an extra hour most days and, so that her mother couldn’t take the extra pence, she left the money safely at the haberdashery shop. Mrs Jones, the owner, had agreed to keep these secret savings and not to mention it to Aggie.

‘We’re here, thank God,’ Aggie said. She hammered on the front door and, when no answer was forthcoming, she shouted through the letter box. ‘Ted, open this bloody door.’

‘Mammy,’ Daisy whimpered, sobbing into the blanket, trying not to make a noise. She didn’t like her angry grandmother. She wanted Mammy.

Aggie banged on the door again.

‘He’s gone.’ It was the next-door neighbour, Mrs Green.

‘What do yer mean?’ Aggie snapped. She had reached the end of her tether and she had to go to work this evening.

‘He came home from work and banged about, and the next thing, he was off with his bag on his shoulder. I asked him where he was going. Said he’d got a ship and was off to see the world. I said, “But what about yer bairn?” He just laughed in my face, the callous bugger.’

After a cup of tea at Mrs Green’s house, Aggie went off to work and Martha made her way home with Daisy.

Once home, Martha had instructions to put the dirty clothes in to soak in the stone fire boiler, then to see to her three brothers who were used to being left on their own in the early evenings. They had made a den under the table and were playing at wild Indians. Upstairs, the three boys shared a bed in the back bedroom and Martha shared a bed with Aggie in the front bedroom. It was into this bed that Martha put the sleeping child. The beds were covered with old blankets and their coats, but they were never warm enough and the palliasse was torn and lumpy. They had no other furniture. What they once owned had either gone to the pawnshop or had been chopped up for firewood. But, according to the authorities, they were lucky to have a whole house to themselves. One thing Martha could say about her mother was that she always paid the rent; even if they went hungry, she kept a roof over their heads, so they would never have to resort to living in an overcrowded house with other families. Many a week they’d lived on potatoes and bread, and once, when Aggie cleaned out a boat on the dock, they’d lived on bananas all week. This house, her mother was fond of saying, was for her old age. It was Aggie’s dream to take in a paying lodger so that she’d only have to work during the day and have the luxury of having the nights to herself.

‘Is our Daisy living with us now?’ asked Jimmy, one of the twins.

Martha shrugged, she didn’t have an answer.

Everyone was in bed when Aggie returned home from work. The wet clothes hung on the pulley above the fire and she sat by the dying embers, drinking a mug of weak tea, re-patching her work dress and thinking. What was she going to do about Daisy? She hadn’t the strength to bring up another bairn, she didn’t want to, nor did she have the money to do so. She gave a heavy sigh. When her lodger started paying her money, she’d be able to give up the evening job. She rubbed the aching stiffness of her arthritic knees. No more scrubbing floors for her.

After a restless night, with Daisy wriggling about between her and Martha, and wetting the bed, Aggie felt more tired than when she went to bed. Her temper was sharp, and everyone kept out of her way.

It was left to Martha to haul the palliasse to the open window and to take an upset Daisy, who kept crying for her mammy, downstairs. This pulled at Martha’s good nature and she felt guilty, and decided that with the extra money she earned today, she would buy food and hoped that Aggie wouldn’t ask where the money came from.

For a whole week Aggie left Daisy with Mrs Yapham when she went to work. But the next day, Mrs Yapham was taken ill and was not able to look after Daisy. There was no one else available. ‘I’ll have ter tek yer with me, so you best keep quiet,’ Aggie threatened Daisy.

The Melton family lived in a tall, three-storey Georgian house with iron railings fronting it and steps leading down to the basement, which was the entrance Aggie used. Baker Street was a prosperous area in Hull and Aggie was lucky to have found employment with such a fine household. But, to her credit, she was a good and reliable worker. This morning, her employer, the lady of the house, Mrs Melton, was at home.

‘Drat,’ muttered Aggie. She pushed Daisy into the outhouse at the back where the washing tub and mangle were kept. Mrs Melton rarely ventured into the basement and never into the outhouse. Aggie spread out a piece of sacking on the stone floor. ‘You can go ter sleep, and no noise and be a good girl.’

Aggie tied on her work apron and set about her daily tasks. She was a good, methodical worker. And, as the morning passed, she went to check on her granddaughter who was fast asleep, curled up and sucking her thumb. She shut the door and went back to her work, and became so absorbed in her tasks that she forgot about her granddaughter until she heard an almighty crash and a child screaming.

Rushing to the outhouse, she collided with Mrs Melton, who had also heard the noise. ‘Sorry, madam,’ Aggie said.

‘Good gracious, what is happening?’

Aggie gave her employer a look of alarm and ran towards the outhouse. Breathing heavily, she pushed open the door to see Daisy, her clothes soaking wet, crouching in a corner, and the washtub tipped over and water flooding the floor.

Aggie covered her mouth with her hands at seeing the chaos of the scene. Her first thought was that she would lose her job.

Mrs Melton was behind her and, at first, speechless.

Half an hour later, with the mess in the outhouse cleaned up, Daisy, wrapped in a towel while her clothes dried, sat at the kitchen table drinking a glass of milk and eating one of Cook’s shortbread biscuits.

Meanwhile, Aggie took off her work apron, which kept clean her wrap-over pinafore that she wore like a uniform and hid the old, patched working dress. She tidied back her grey hair, which she wore in a bun at the nape of her neck and knocked on Mrs Melton’s sitting-room door. She was asked to enter and, as she did so, she bobbed a curtsey. This was not usual for her to do, but she thought it might help. Aggie told Mrs Melton every detail of how she came to have her granddaughter staying with her. When she had finished, the room filled with an uneasy silence.

Then Mrs Melton spoke. ‘Do you know where your daughter is?’

‘I’ve no idea where she’s gone,’ Aggie said, desperately. ‘It’s the bairn. I can’t work and look after her, and I need my wages from you to feed and clothe my own bairns, and to pay the rent. I don’t know who else to turn to.’ Aggie lowered her eyes, but not before she saw the look of sympathy on the face of her employer.

‘Have you spoken to the authorities?’ Mrs Melton asked.

Aggie gulped. She mistrusted the authorities who would come snooping around. They’d once tried to evict her from her house. ‘No, Mrs Melton,’ Aggie answered, demurely.

‘Very well, leave it with me and I will see what can be done to help your awkward situation.’

‘Thank you, madam,’ Aggie replied, dipping her arthritic knees. And before the mistress changed her mind, she then scuttled from the room. In the passageway, she heaved a great sigh of relief. Her job was safe and soon Daisy would be gone.

Chapter Two

The bright light hurt her eyes and, when she tried to move, her head ached. After a while, she tried to focus her eyes, but she could only see white clouds billowing around her. She felt weightless and her body seemed to be floating away. She was in heaven. She had died. A great pain of fear gripped her before darkness surrounded her again.

When she next opened her eyes the darkness was still around her. But, as her eyes became accustomed to the gloom, she was surprised to see a sleeping figure in a bed next to her. She didn’t know they had beds in heaven. Then she saw a glimmer of light. It was coming from a small lamp on a table and sitting at the table was a woman in nursing uniform. How strange, she thought.

As if aware of the young woman waking up, the nurse left her post and quietly came towards the bed. ‘So, you are awake at long last,’ said the nurse in a soft voice. She checked the patient’s pulse and blood pressure, and seemed satisfied with the results.

‘Where am I?’ asked the patient, in a barely audible voice.

‘You are in hospital. You were involved in a road accident. What’s your name, dear?’

Words formed on the young woman’s dry lips, but no sound came from them and the skin on her face felt taut, and her eyes hurt with the effort of focusing. The touch of the nurse smoothing the bedcovers lulled her back into the safety of sleep.

When she next woke, it was to see a doctor and a nurse standing by her bedside. The nurse held a chart, and both she and the doctor were studying it. At the sound of stirring from the bed, both looked down at the young woman.

The doctor spoke in a brisk tone. ‘Young woman, you have made a moderate recovery, considering your serious injuries.’

‘My injuries?’ the patient asked. ‘What injuries?’

‘You were involved in a traffic accident and you suffered critical injuries: internal bleeding, damage to your back and pelvis, a broken leg and a fractured skull, and you have suffered a certain amount of memory loss.’ On seeing the fear on the patient’s face, he continued in a softer voice. ‘However, under our excellent nursing care, your health will be restored, given time.’ He smiled reassuringly at her. Then he asked, ‘Can you recall anything of the accident? Or your name, so that we can contact any family members you may have?’

The young woman looked puzzled, the pale skin of her face puckered in concentration, then tears filled her eyes and she bit on her lip but didn’t speak. She closed her eyes, trying to remember who she was. Or was she trying to forget who she was? She wasn’t sure what she felt because everything was so mixed up in her aching head.

The doctor and the nurse must have assumed she was asleep, because they began to discuss her case and she could hear them as they stood at the foot of her bed.

‘Very odd,’ said the doctor, ‘that no one has reported her missing.’

‘I understand that the police made enquiries, but no one came forward to identify the woman,’ the nurse replied. Then they moved on out of earshot.

For a long time the young woman kept her eyes shut, but she was not sleeping. She was trying to think. Fragments of words seemed to be floating around in her head, but she couldn’t grasp what they were.

Over the days that followed, she became known as Mrs Thursday, so called because she was admitted on a Thursday night to the cottage hospital on the eastern fringes of the city after a road accident, wearing only a nightdress. She shuddered at the thought, and a sense of being wet and cold filled her with fear. So, why hadn’t anyone come forward to identify her? Did she not belong to anyone?

As each day passed, Mrs Thursday developed a strong determination to get better and pushed herself hard. But nothing could take away this strange feeling of not knowing who she was. Someone, somewhere, was waiting for her, someone needed her, but she wasn’t sure who. Her broken leg was healing slowly, the pain in her back became easier and each day, with the aid of two sticks, she managed to walk around the ward. She still suffered from headaches, but was told by the doctor that, gradually, they would cease. He was quite concerned about her amnesia and she’d overheard him discussing this with another doctor.

‘It is as if she does not wish to recall her past. And why was she running through a cold, wet street in just a sleeping garment?’ One doctor had suggested that it could have been a form of sleepwalking.

Today, accompanied by an orderly, she was allowed to take a short walk in the grounds. Stopping for a rest, she leant on her sticks to admire the view of the green fields beyond the grounds. She felt a jolt. A spark of recognition of something from her past, she felt sure. She tried to recall it, to reach out to it, but it vanished. Tears wet her lashes, and she felt agitated and angry. ‘I want to know who I am,’ she cried out.

‘There, there, Mrs Thursday,’ said the orderly, glancing at her watch. ‘Time for your rest now.’

Exhausted, she lay on her bed, but sleep refused to come. Her mind was whirling like a spinning top as she tried to recall names, but they were elusive as they fluttered in and out, and she couldn’t catch hold of them.

Eventually, she drifted off to sleep, but the same dream she’d dreamt before plagued her mind. And she experienced a sense of foreboding, something so dark and frightening. Always it was the same evil-faced man who towered above her, driving her into a black hole of fear.

The same terrifying dream occurred again that night, but it was different because a child appeared. She was hiding in a corner and, just as the man was about to pick her up and throw her in the air, a woman screamed out loud. Mrs Thursday woke up, sobbing and fighting for air. She clutched at the night nurse who had hurried to her bedside, crying, ‘Don’t let him hurt her.’ She could taste the fear in her mouth and feel it crawling on her skin, and the strong smell of beer filled her nostrils. Wildly, she lashed out with her arms.

‘Shush, you’re safe,’ the nurse soothed, beckoning to the probationer nurse. ‘Call the duty doctor,’ she ordered. Then she held the sobbing woman in her arms in an attempt to quieten her, so as not to further disturb the other patients.

The doctor came. ‘A nightmare, I believe,’ said the nurse and then watched as the doctor administered a sleeping draught.

The nurse stayed by Mrs Thursday’s bedside until she slept and then she went back to her post to write up her report.

The woman slept until mid-morning. She was regularly checked by the probationer nurse who reported to the staff nurse that Mrs Thursday was awake.

‘Don’t just stand there wasting time,’ the harassed staff nurse admonished the probationer. ‘See to the patient.’

The probationer, Judy, was a willing worker and soon had the patient toileted, washed and bedlinen changed, and prepared a late breakfast of tea and bread and jam.

The woman lightly touched Judy on the arm and said, in a quiet voice, ‘Thank you.’

‘That’s all right, Mrs Thursday,’ said Judy, cheerfully. Then she scurried off to return to her task of cleaning out the lavatories or she’d miss her dinner break.

A few days later, in the afternoon, Mrs Thursday was sitting up in bed, reading a magazine passed to her by the woman in the next bed. It was visiting time and a lonely hour for her, because no one came to see her. It seemed that she was alone in the world, but somewhere … If only she could remember. The nightmare dream blocked her way and stopped her from moving forward.

She tried to immerse herself in the story she was reading, but her interest waned. She flicked over the page, seeing an article on fashionable dresses, coats and hats to suit all tastes. Had she ever worn clothes like these? She traced her fingers over the garments, willing a spark of recognition to ignite, but nothing happened. She couldn’t languish for ever in a hospital bed – she had to find out who she was and then, maybe, the nightmares would go away.

‘Alice Goddard, fancy seeing you here.’ The voice cut into Mrs Thursday’s thoughts.

Startled, she looked up to see a middle-aged woman standing at the foot of her bed.

Oblivious to Mrs Thursday’s bewilderment, she continued on. ‘Is yer fancy man coming to see you, then? I wouldn’t mind a look at him. Is he a film star? He must be for you to leave that bonny daughter of yours. Don’t you miss her?’ the woman gabbled.

Mrs Thursday stared at the woman, her mind blank.

‘Is there something wrong, Mrs Thursday?’ said the ward sister, coming to stand by the side of her bed, having heard the visitor’s loud voice.

‘So, that’s who yer calling yerself.’

‘Madam, could I have a word with you in my office?’ the sister asked, politely.

‘But I’m here to see my friend, not her.’

‘I will only take a few minutes of your time. Please, this way.’

Mrs Thursday watched them go, puzzled. The woman seemed to know her and called her a strange name. Alice Goddard. It meant nothing to her.

The ward sister was in Matron’s office having a welcome cup of tea with her as she reported her findings. ‘It appears that this woman is a neighbour of Mrs Thursday’s mother, a Mrs Agnes Chandler, and the woman we refer to as Mrs Thursday is her married daughter, Mrs Alice Goddard.’

Matron replied, ‘We must inform Mrs Chandler immediately. I will see to that. You must inform the doctor and he must be present when the patient, Mrs Thursday, is told of the facts as we know them.’

Aggie Chandler was having a well-earned snooze before teatime, when a loud knock sounded on the door. At first, she ignored it. Then it became more persistent. ‘All right, I’m coming,’ she muttered.

On opening the door, she saw a police constable standing there. ‘Mrs Agnes Chandler?’ he asked.

The first thing that flew into Aggie’s mind was one of her lads had got up to mischief. ‘Yes,’ she replied, her face set in anger.

‘Your daughter.’ He glanced down at his notebook. ‘Mrs Alice Goddard is in the Cottage Hospital suffering from loss of memory and you are requested to identify her.’

Aggie stared open-mouthed at him, lost for words.

The constable continued, ‘You are to report to the matron at the hospital as soon as possible.’ He shut his notebook and waited for Aggie to confirm.

She nodded, then said, ‘Me bairns. I’ve ter get their tea.’

‘You go, Aggie. I’ll tek care of bairns.’ It was her next-door neighbour who was standing on her doorstep, listening to the constable’s words.

Aggie, still in her working clothes, arrived at the hospital out of breath and told her story to the porter on duty. He directed Aggie to the matron’s office.

Matron was pleasant but efficient as she explained the facts and then escorted a confused Aggie to the ward where her daughter had been for the last six weeks. The matron’s story differed from the story that Ted had spun her. In her heart, Aggie never believed that her Alice would leave her daughter to run off with another man. Things were in a right mess and how could she tell Alice about her daughter? Her heart sunk down to her shabby boots.

Matron glanced at her, saying, ‘This must have been quite an ordeal for you.’

Aggie was shocked at the figure of the young woman lying in the hospital bed. She was so thin and pale, a shadow of the Alice she knew. At once she was by her side, clutching at the thin, frail hand that rested on the bedcover. ‘Oh, my Alice! What’s happened to you?’

The woman in the bed stared, looking bewildered at first and then a spark of recognition flickered across her eyes. ‘Are you my mother?’ she whispered.

‘Of course I am and you’re my Alice.’ One of the probationers brought a chair for Agnes to sit on and she sank wearily onto it.

‘Do I live with you?’

‘No, you’re married.’

A dark shadow crossed Alice’s face and fear filled her eyes as she slipped further down into the bed.

Matron put a hand on Agnes’s shoulder and said, quietly, ‘Let her rest for now. It has been quite distressing for you both.’ She led Agnes back to her office where a ward-maid served them both a cup of tea.

Agnes’s hands were shaking as she held the cup of sweet tea to her parched lips. After a few sips, she spoke. ‘I never expected to find Alice in hospital. Will she be all right?’

Matron smiled and said, reassuringly, ‘Alice’s injuries have almost healed and will have no lasting effect on her health, however …’ She paused, choosing the right words. ‘It was her loss of memory that was causing the most concern. However, now you have identified her and she recognises you, she should recover quickly.’ She rose to her feet, saying, ‘Thank you, Mrs Chandler, for coming. You may visit your daughter tomorrow afternoon.’

Agnes murmured her thanks. Slowly, she made her way home to check on her lads and that Martha was home from work to make sure they were cared for. She didn’t want anything else to happen. She was getting too old for worry. Since Albert had died, that seemed to be her lot: work and worry. And just when she thought she was turning a corner, trouble pounced on her.

Chapter Three

When her mother had gone, Alice closed her eyes. She wasn’t asleep, but she wanted to think. She must try to remember how she came to be in hospital. She felt sure it was to do with the dreams, the nightmares she’d been having. All she knew was what the doctor had told her, that she’d been involved in a motor car accident and was only wearing a nightdress when admitted to hospital. So, had she been sleepwalking or running away from something or somebody? The scenario played over and over in her mind until her eyelids felt so heavy, as if someone was standing on them, that she finally succumbed to sleep.

‘You’ve had a good night’s sleep,’ said the nurse who came to check on Alice the next morning.

Alice yawned and stretched, then said, ‘Have I really slept right through the night?’

‘Yes. A good sign that you are improving,’ the nurse replied.

Later, after breakfast, washed and wearing a clean nightgown, Alice did, indeed, feel so much livelier in body and mind. She sat on her bedside chair trying to recall things from her past. A child’s cry interrupted her thoughts and she turned, but there was no child to be seen. She eased herself up from the chair reaching to see further round the ward and nearly overbalanced. A probationer nurse came hurrying to her, steadied her and stopped her from falling.

‘Do be careful,’ she said, taking hold of Alice’s arm and lowering her gently back onto the chair.

Settled and safe, Alice said, ‘I thought I heard a child crying.’

The probationer glanced round and replied, ‘Children are not allowed on the wards. Perhaps the sound came from outside.’ She motioned to the open window.

Strange, Alice thought, it was as if the child was quite close by.

Later that afternoon, Aggie came to see Alice. She wasn’t in her working clothes and had made an effort with her appearance, wearing the only coat she possessed and her best black felt hat to match her coat. Her boots were well polished, but the soles were thin and needed mending. She had been hoping to buy a new pair, but her lodger, now installed, needed a wardrobe, something she hadn’t thought of. She sighed heavily. Soon, the lads would need new boots too. She’d be glad when the twins left school and were working full-time. At the moment, both earned a few pence by running errands for neighbours and, when someone wanted to put a bet on a horse they’d act as bookie’s runners, taking care to avoid police constables.

Entering the ward, Aggie forced a smile on her face. She was dreading having to tell Alice about Daisy. ‘Now then, lass, how are yer today?’ she said, sitting down on an uncomfortable visitor’s chair by her bedside.

Alice replied, saying the one thing that kept reverberating in her head, ‘I heard the voice of a child, a little girl’s voice. Do I have children?’

Aggie caught her breath and swallowed hard, not sure how to tell her daughter the truth so, instead of answering the question, she asked one of her own. ‘What do you remember?’

Alice closed her eyes, remembering, and said out loud, ‘It was a dark, wet night and a man, a big, frightening man, was coming after me.’ The voice inside her head became louder and she heard the distinct cry of a little girl. ‘Have I a daughter?’ She opened her eyes wide to stare into Aggie’s horrified ones.

‘Yes,’ Aggie muttered. ‘Ted brought her to me when—’

Alice cut in. ‘Ted, is he my son?’

‘Lord, no! He’s yer husband. He brought little Daisy to me, telling me you’d run off with another man.’

Fearfully, Alice looked round the ward, saying, ‘I don’t want to see him.’

‘He’s long gone. Heard he’s got a ship and gone off ter see the world.’

Alice relaxed and said, ‘I wish children were allowed to visit. I’m longing to see my little girl. Tell her I love her, won’t you?’

Aggie felt her blood run cold. She couldn’t meet her daughter’s gaze, so she bent down, pretending to pick up something from the floor. After more stilted conversation, the bell rang for the end of visiting time. Quickly, she was on her feet, saying her goodbyes, with a promise to visit at the weekend.

Alice watched her mother hurry down the ward until she disappeared through the door. ‘I have a daughter,’ she said to the woman in the next bed.

‘That’s nice, love. What’s her name?’

‘Daisy.’ She whispered the name over and over to herself, smiling happily. She couldn’t wait to see her.

The next day, the doctor and the ward sister, on their daily round of the wards, stopped at the foot of Alice’s bed and picked up her chart to study. ‘I am pleased that your memory is returning and, if all goes according to plan, we will soon be discharging you.’ He smiled at her and they moved on to the next patient.

Alice felt a warm glow of excitement. She was longing to see her daughter and hold her in her arms. All afternoon she thought about her daughter, remembering her fair curly hair, big blue eyes and a lovely smile. And then she frowned. Would her daughter know her after all these long weeks apart? What if she doesn’t?

‘Bairns never forget their mammy,’ said the woman in the next bed when Alice confided her fear.

Reassured, that night her dreams were sweet. The big, horrible, frightening man had disappeared, hopefully gone from her life.

On Sunday afternoon, Alice, her face shining with happiness, waited for visiting time. At last, the door opened and visitors came streaming in. Alice was surprised to see a young woman come to her bedside. Puzzled, she studied the young woman, watching as she sat down on the chair.

‘It’s me, your sister.’

Alice stared at the young woman who was smiling at her, and then a hint of recognition flickered and she knew. ‘You are Martha!’ Her face lit up with pleasure, and she held out her arms to embrace her. Both young women settled back. ‘Where’s Mam?’ Alice said, looking round.

Martha’s face became sombre and said, ‘She’s sorry, but she has to get the lodger’s washing and ironing done.’

‘A lodger?’ Alice queried.

‘Yes, he pays her for board and lodgings each week, so that she doesn’t have to work of a night. She said she’s getting too old for that.’

Alice nodded, saying, ‘I suppose it makes sense. What’s he like?’

‘Bit of a stuffed shirt. He won’t bother me because, as soon as I’m eighteen, I’m moving out.’

Alice looked at Martha and could see how grown-up she now was. Now, with family business out of the way, she asked, ‘Tell me how my Daisy is. Is she missing me?’

Martha looked startled by the question. ‘Daisy? I don’t know. Why should I?’

Now it was Alice’s turn to look startled as she responded, ‘But she lives with you. Mam said Ted brought her to your house.’

Martha looked down at the highly polished wooden floor, wishing it would magic her away. But she couldn’t just get up and run. Mam had left her to do the dirty work. She hadn’t told Alice. At last, she raised her head, took a deep breath and let it out slowly, and then said, ‘Mam took Daisy to the authorities.’

Stunned, Alice felt her insides turn to ice, and then she spoke. ‘Authorities, why?’

Martha shrugged, feeling ill at ease. She stuttered, ‘Mam said she couldn’t cope with another bairn.’

‘How could she do that to her own granddaughter?’ Anger, mixed with fear for Daisy, filled her.

‘Ted told her you’d run off with another man. She did what she thought was best.’

‘But, I didn’t run off. I’ve been in hospital all the time.’

‘Sorry,’ muttered Martha, wishing she was anywhere but here.

Alice fell back on the pillow, her eyes filling with tears at the thought of Daisy being with strangers.

For the rest of the hour, the sisters barely spoke.

When the bell rang, Martha jumped up from the chair, saying, ‘Goodbye.’

‘Wait,’ Alice commanded. Martha stood stiffly, anxious to be gone. ‘Tell Mam I need to see her on the next visiting day. I need to know all the facts.’

When her sister departed, Alice slipped further down the bed, wondering how she would get through the time until the next visiting day.

Later on, when the nurse was doing her rounds, she remarked, ‘Your blood pressure has risen.’ Alice didn’t reply. ‘Any reason?’ asked the nurse.

Alice shook her head. She didn’t want to speak about it.

The days passed so slowly and, at last, it was visiting afternoon. As the visitors entered the ward, there was no sign of Aggie.

After twenty minutes, a lone figure moved slowly down the ward. Aggie stopped at the foot of the bed, staring down at Alice, and then said, ‘I believed Ted when he said yer ran off with another man. What was I to think or do? I had to find help.’

‘I need the details, so I can go and get my daughter back from the authorities.’

Aggie, still standing, shrugged and said, ‘I ain’t got any details.’

‘You must have something?’

‘No, they didn’t give me nowt.’

Alice sat up straight. ‘They can’t just take a child without the necessary forms.’

‘Well, they did,’ Aggie replied, stubbornly. ‘If I’d known you were in hospital, I would have come to see you and sort it out. But nobody told me nowt.’

‘I didn’t leave Daisy on purpose, I was going for help.’

‘Yer did. That’s why Ted brought her to me,’ Aggie shouted.

The woman’s visitor at the next bed frowned at her.

Ignoring her, Aggie continued, ‘I’m sorry. I really didn’t know what ter do.’

Alice stared at Aggie, barely comprehending.

Aggie pulled her shawl closer around her neck and huffed. ‘All I know is she has gone to a good home. And, before yer start, I don’t know where.’

‘But you must know.’

‘I don’t know. I was at my wits’ end. What do yer think I could do? I’ve enough hardship in my life without tekkin’ on yours.’ Then she muttered, ‘I’m sorry, lass.’ She screwed up her face, suddenly remembering something. ‘They said it was only for now, till yer came back.’ Redeeming herself, Aggie stood up to leave.

Alice sank back on the pillow.

Aggie was hurrying along the corridor when someone called her name. ‘Mrs Chandler, may I have a word with you, please?’ Matron stood in the doorway of her office.

Aggie was taken off guard and stared open-mouthed, wondering, What now? She followed Matron into her office and sat on a chair in front of the desk. She felt self-conscious of her appearance in her work clothes, and wished she’d put on her coat and hat.

Matron smiled politely and said, ‘Your daughter, Mrs Goddard, will soon be discharged into your care. Do you require any help with arrangements?’

Aggie just gawked.

Matron continued, ‘I can arrange for transport to take her to your home and have a nurse accompany her.’

‘But she can’t,’ Aggie uttered in a squeaky voice.

‘Do you mean you wish to accompany Mrs Goddard from the hospital?’

‘I ain’t got no room for her. Me house is full now I’ve taken in a lodger.’ She stood up, pulling her shawl tightly around her. ‘I’m sorry,’ she mumbled, and took flight from the office and the hospital.

Once outside, she realised she was trembling from the top of her grey hair to the tip of her worn boots. She needed to get home and have a cup of strong tea.

Aggie’s bad news took its toll on a distraught Alice. Her temperature shot up and so did her blood pressure. The nurse, recording this on Alice’s chart, asked, ‘Have you been upset?’

Tearfully, Alice blurted out about what Aggie had told her about her daughter, Daisy. ‘I need to find her.’

‘Of course you do, but you must stop fretting and concentrate on a full recovery, and then you can find where your daughter is.’ The nurse made Alice comfortable and then she went to report to the sister about the deterioration of Alice’s health and the probable cause of it.

After a consultation involving all the hospital staff concerned, the consensus was that Alice would benefit from a few weeks of convalescence. The nearest one with a vacancy was Bridlington, on the east coast, about twenty-five miles away. Arrangements were made, and Alice was told this was in her best interest, if she was to make a full recovery.

Chapter Four

A nurse accompanied Alice to the convalescent home. And on the journey from the hospital, in a transport vehicle to Paragon railway station, she searched the children playing in streets and down alleys for Daisy, her beloved daughter. Her thoughts seemed to be rambling in her head and her big question was how could Ted have deserted their innocent child? If only she hadn’t run from the house. But this attack had been so vicious, worse than the others, and she’d feared for her life and Daisy’s. If only she could have foreseen the terrible consequences that had followed. Everything − the relentless brutality she’d suffered, and why she was running to the police station for help − flooded back to her, though she had no recollection of being hit by the car. Fate had dealt her a hard blow. Now, her paramount aim was to find her beloved daughter.

The train ride was uneventful. Alice sat quietly, staring out of the window, her companion, a nurse in her thirties, said she was glad of some peace and was happy to read her novel.

They arrived at the Regency Convalescent Home, Bridlington, which was situated facing the promenade and the North Sea. By now, it was mid-afternoon and Alice felt tired. After a welcoming cup of tea, she was shown up to the room that she was sharing with another lady. The walls of the room were painted a restful shade of pale green and the bed linen was pure white, in contrast to the dark chest of drawers and the wardrobe. She went to sit down on the edge of the narrow bed that was hers and dropped the old attaché case containing a few essential clothes, donated to her by the hospital charity, at her feet. The bed felt soft and inviting to her touch as she ran her hand over the coverlet. She untied her boots and eased her weary body down on the bed. She thought that at once, on leaving the hospital, her strength would return, but she felt absolutely drained of energy. A gentle breeze drifted in through the open window, playing with the curtains, and the peaceful sound of the sea lapping onto the sand soon lulled her to sleep.

She slept so soundly that she didn’t wake up when her room-mate came to bed.

The next morning, after a good night’s sleep, she felt refreshed in body and mind. Her room-mate said a quick hello and left the room. Alice washed and dressed and went down for breakfast. She was shown to a window table with three other people. There was a retired schoolmistress, who was recovering from a delicate operation, a shop assistant, recovering from an eye operation, and a nurse recovering from a back injury. The nurse, Evelyn Laughton, was the patient with whom Alice was sharing a room. She was tall in comparison to Alice, and she had warm brown eyes and dark wavy hair cut in a bob. Alice took an instant liking to her. They chattered quite amicably, though Alice mostly just listened to the others talking. She wasn’t ready, if ever, to talk about her missing daughter or her estranged husband.

After breakfast, Alice set off for a solitary walk along the promenade. Though the sun shone, a cold wind was blowing off the sea. All the clothes she had were from a charity that helped destitute people. She hadn’t realised that there were such good people willing to help. If only there had been someone from whom she could have sought advice, or spoken to, about her husband’s cruel treatment of her. But a married woman was expected to make the best of her marriage, good or bad, so she’d suffered in silence until … She shuddered, stopping to lean on a railing, and to look out to sea and the far horizon. Tears filled her eyes. She yearned to hold her daughter close and keep her safe. Where was she? And who was she with? Did they love and care for her, and treat her well? She desperately hoped so.

One day, Evelyn asked Alice, ‘May I walk with you?’

Alice hesitated, because she wanted to walk on her own with only her thoughts for company, but it would be rude to refuse, so she smiled and nodded.

They strolled in silence towards the north end of the town, which was livelier, with more people about, taking the fresh sea air.

It was Evelyn who spoke first. ‘What will you do when you leave here?’

Without thinking, Alice replied, ‘Find my daughter.’

‘Your daughter?’

Tears wet Alice’s lashes and she felt so sad. Gently, Evelyn took hold of her arm and led her to a sheltered area with wooden seating, away from the prying eyes of other people.

Alice unburdened herself and told Evelyn her sad, worrying story. When she finished, she felt a great relief to be able to tell another person of her suffering and her missing daughter.

Evelyn showed compassion, but she was also practical. ‘First, you will need somewhere to stay. Has anyone spoken to you about what you will do when you leave here?’

Alice shook her head.

‘I can arrange for you to see the matron in charge of the convalescent home. She may be able to help.’

The next day, Alice waited with trepidation outside the matron’s office. She’d only spoken briefly to the matron when she first arrived and then seen her when she made her daily rounds. Alice checked her appearance in the small mirror on the wall. Her fair hair was still raggy and patchy from her head injury, but she’d combed it to hide the scar. Her face shone clean, and now showed a touch of pink on her cheeks from the fresh sea air on her daily walks. The dark-green dress she wore was of fine wool, with neat collar and cuffs – though rather faded, it was serviceable. Once, she surmised, it must have belonged to someone with money and class.

She jolted as the door of the office opened and a plain-looking woman dressed in grey said, ‘Matron will see you now.’

Alice entered the office. Matron was sitting behind a large oak desk, writing. She didn’t look up and the only noise in the room was the scratching of her pen. Alice’s gaze took in the sombre room of dark brown walls where there hung a row of photos of past matrons of the establishment. Alice could feel the leg, which she’d broken in the accident, begin to hurt with standing still. Placed near to the big desk was a chair, which looked inviting, and she longed to sit down on it, but dared not until she was asked.

‘Mrs Goddard.’ The voice from the desk spoke.

Alice pulled her body up taller and gave her full attention. ‘Yes, Matron,’ she replied, hoping her voice didn’t betray the nervousness she felt.

‘I understand you are homeless and without funds,’ the matron stated, bluntly and directly.

‘Yes, Matron.’ She felt ashamed at her predicament. Not only did she not have a home or any money, she had also lost her daughter. What kind of woman and mother was she? A lump caught in her throat and she swallowed hard, not wanting to cry and show such weakness before this competent and astute-looking woman.

‘There is not much to offer you – there is the workhouse.’ Matron looked at her.

Alice’s heart filled with dread at the mention of the workhouse and she felt the hairs on the back of her neck prickle with shame at the thought of being an inmate there.

‘However,’ Matron continued, ‘there is a live-in position at Faith House, in Hull, a home for fallen girls. As you have experience of being a housewife, part of your duties will be to instruct the girls in how to manage certain aspects of a home and prepare them for life once they leave Faith House. The girls can be difficult and may not want to conform to life in an institution.’ A faint smile touched her lips as she said, ‘I know from first-hand experience, as I once held a position there. It is hard work and the hours are long, with not much free time for being off-duty. Are you capable of this?’

Surprised and wide-eyed at such a challenge, Alice answered, ‘Yes, Matron,’ and then added, ‘I will do my very best.’ She would have liked to have asked how she should go about reuniting with her daughter. For now, she would have a place to work and live. And, in her free time, she would find out where Daisy was.

Alice went to look for Evelyn and found her in the sitting room reading. Quietly, she entered the room, curbing her excitement of getting a job.

Evelyn looked up and closed her book. ‘Come and sit down, and tell me your good news.’

‘How can you tell it’s good news?’

‘By the sparkle in your eyes. You’ve looked sad and been subdued all the time you’ve been here.’

Alice sat down and told Evelyn what had transpired with the matron. She finished by saying, ‘Thank you, Evelyn, for all your help.’

Evelyn smiled and said, ‘We must keep in touch because I will want to hear how you get on at Faith House.’ They exchanged addresses. Evelyn was a nurse at the infirmary in one of the men’s wards and lived in the nurses’ quarters near Prospect Street as her family lived in the market town of Beverley, which was too far for her to travel from daily.

On her last day at the convalescent home, Alice set off alone and turned right for her walk towards the south end of the town. She strolled along the promenade and went further than she intended, to where there were fewer people about and the sands were deserted. Feeling tired from walking so far, she sat down on a wooden bench facing the sea. There were no screeching gulls, so it was quiet and peaceful. She looked towards the sea, mesmerised by the incoming tide gently lapping on the fringe of the golden sands, its white frothy foam reminding her of her childhood days when she bathed in a tin bath in front of the fire. She’d create lots of bubbles to cover her budding body, which gave her privacy from the prying eyes of her young siblings. There had been no privacy in a small, crowded house.

Then her thoughts turned to Daisy. Would she be fretting for her? Alice felt determined to find out where her daughter was. As soon as she returned to Hull and settled into her job, she would make plans and start her search. She rose from her seat and walked along the promenade, feeling light-hearted and positive. Someone, somewhere, would know where Daisy was.

In a big house in the village of Elloughton, on the outskirts of Hull, in a large pink bedroom full of fluffy toys, a little girl, in a bed of snowy-white covers decorated with rosebuds, cried for her mammy. Every night the pillow was wet with her dewy tears.

‘She’s wet the bed again, madam,’ said the housekeeper.

Mrs Cooper-Browne set down her breakfast cup, her brow furrowing. ‘I’m at a loss what to do with her. I’ll speak to the doctor again. See that she’s bathed before you bring her down.’ Dismissively, she turned to pour herself another cup of tea.

The housekeeper went back upstairs to bathe the little girl and dress her in one of those ridiculous frilly dresses.

‘I want Mammy,’ the little girl cried, sobbing and hiccupping as if her little heart would break.

The housekeeper gently wiped the child’s eyes. ‘Now, try and be good for Mrs Cooper-Browne and then I’ll let you help me bake jam tarts.’ She kissed the top of the golden curls and took hold of the girl’s hand to take her downstairs to that cold fish of a woman who was pretending to be a mother.

‘Poor little mite, she’s fretting away,’ said the housekeeper to her husband as he came into the kitchen from his gardening duties. ‘She should be with her own mother.’

He lit a cigarette and mumbled, ‘Nowt to do with us. We just do the job we’re paid to do and don’t you forget it.’

She turned away, feeling so helpless.

Chapter Five

Alice journeyed back to Hull by train and walked from the station, through the city centre, crossing over the River Hull by the North Bridge, to the area of Witham. Arriving at her destination, she stood on the pavement looking up at Faith House, a rescue home for fallen girls. It was an imposing late-Victorian three-storey building of local brick. She glanced to her right down Holderness Road, which led to East Park where, when she’d saved enough money for the tram fare, she would take Daisy and … She brushed away the single tear trickling down her cheek.

Gripping the handle of the small attaché case tightly, and ignoring the fluttering of apprehension in her stomach, she marched up the steps to the front door. The heavy brass knocker sounded loudly, and she felt surprised at her strength to make it do so. A young girl in a dark-blue dress and white pinafore opened the door.

Without hesitation she stated, ‘I am Mrs Goddard and I’ve an appointment to see Matron.’