8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

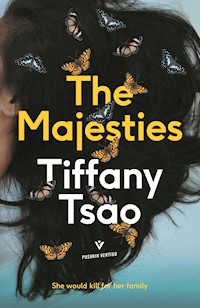

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

When your sister murders three hundred people, you can't help but wonder why 'Tiffany Tsao's visceral debut...reads a bit like Crazy Rich Asians if the book began with familicide instead of romance" CrimeReads Gwendolyn and Estella are as close as sisters can be. But now Gwendolyn is lying in a coma, the sole survivor after Estella poisons their entire family. As Gwendolyn struggles to regain consciousness, she desperately retraces her memories, trying to uncover the moment that led to such a brutal act. Journeying from the luxurious world of Indonesia's rich and powerful, to the spectacular shows of Paris Fashion Week, and the melting pot of Melbourne's student scene, The Majesties is a haunting novel about the dark secrets that can build a family empire - and bring it crashing down. Tiffany Tsao was born in San Diego, California, and lived in Singapore and Indonesia through her childhood and young adulthood. A graduate of Wellesley College and the University of California Berkeley, where she earned a PhD in English, she has taught and researched literature at Berkeley, the Georgia Institute of Technology, and the University of Newcastle, Australia. She holds an affiliation with the Indonesian Studies Department at the University of Sydney. Her works include short fiction, poetry, literary criticism, and translations and have been published in Transnational Literature, Asymptote, Mascara Literary Review, LONTAR, Comparative Literature, Literature and Theology, and the anthology Contemporary Asian Australian Poets.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Named one of the most anticipated books of the year by The Millions, CrimeReads, HelloGiggles, and The EveryGirl

“The Majesties, although it rolls out easily, troubles deeply, haunting and even chilling its reader well beyond the final page”

New York Journal of Books

“Tsao spins a Crazy Rich Asians-esque saga of family wealth and deception as a nasty-fun murder mystery chronicling the events leading up to a woman’s poisoning of her extended clan”

Entertainment Weekly

“A dark, delicious tale that will creep its way into your brain and leave you examining your own soul for signs of moral rot. I downed it in one greedy shot”

Jade Chang, author of The Wangs vs. the World

“Tiffany Tsao’s visceral debut… reads a bit like Crazy Rich Asians if the book began with familicide instead of romance… Why not start off the new year with the perfect tear-it-all-down read?”

CrimeReads

2“Tsao cannily pulls back the gilded surface from a wealthy Indonesian family, revealing a rotten core…. the narrative unfolds in a manner that’s both suspenseful and creepily claustrophobic”

Publishers Weekly

“The Majesties is a thrilling, tender page-turner, the darker side of Crazy Rich Asians”

Krys Lee, author of Drifting House

“One of the most gripping, original and enlightening novels of the day”

SA Weekend

“A sharply realized page-turner with a brilliant twist, written with an effortless command of pace and suspense”

Sydney Morning Herald

“A sobering look at the dark side of extreme wealth among Chinese families in Indonesia… Tsao’s depiction of domestic abuse is powerful”

Kirkus

“Tsao deftly juggles a large cast of characters, and her thorough examination of the life of a wealthy Chinese-Indonesian family, as well as her insights into the false assumptions those in the Chinese, Indonesian, and Western communities make about its members, are intelligent and lively”

Booklist

“A compelling page-turner… a chilling novel about what a family is capable of for the sake of maintaining illusions and the desperate, destructive ways that its entrapped members must take in order to escape”

Intan Paramaditha, author of Apple and Knife

“Tiffany Tsao’s novel of sisters Gwendolyn and Estella is haunting, disturbing and vivid. It is one of those novels that has such a strong opening chapter that I questioned if the author would be able to meet my expectations for the rest of the novel. But meet them she did”

Readings

3

5

For Amanda

6

Keep me as the apple of your eye; hide me in the shadow of your wings …

—Psalm 17:8

8

Contents

The Majesties

1

when your sister murders three hundred people, you can’t help but wonder why—especially if you were one of the intended victims—though I do forgive her, if you can believe it. I tried my best to deny the strength of family ties when everyone was still alive, but now I realize the truth of the cliché: Blood does run thick. Even if poison trumps all.

It was caught on surveillance tape, so there’s no denying that Estella was the culprit. I haven’t seen the footage myself—can’t see at all in my present condition—but I can imagine it with great clarity. At the mouth of the corridor leading from the hotel ballroom to the adjoining kitchen, my sister appears. The angle of the camera makes it difficult to see her face, obscured by the enormous hair-sprayed chignon atop her head, but I’d recognize those calves anywhere—peasant’s legs, our mother always jokingly called them, disproportionately bulky for Estella’s otherwise slender frame. Graceful in stilettos, despite her country-bumpkin appendages, she glides out of one camera’s purview into another’s. My mind’s eye sees her in the kitchen now, speaking to one of the staff, who grants her immediate entry upon learning that she’s Irwan Sulinado’s granddaughter. Graciously, she offers a pretext (a mission to reassure a germophobic aunt, perhaps—any excuse would have served since, in Indonesia, the wealthy don’t need reasons). They allow her free passage, “Silakan, Ibu”—ma’am, as you please—and let her sail on, past flaming woks and stainless-steel bins of presliced meats and vegetables, fielding deferential nods from surprised and frazzled cooks. Only when they resume their duties does she strike, pulling a tiny vial from inside the high, stiff collar of her silk cheongsam and scattering its contents into the great steaming tureen of shark’s fin soup with a flick of a jade-bangled wrist.2

I’m making this whole scene up, of course, except for the cheongsam: a gorgeous gold-and-emerald affair covered in delicate coiling vines that she’d bought years ago on vacation in Shanghai. That’s where my mind beats out the security cameras; such fine embroidery would never have registered on tape. Similarly, I bet the recording didn’t catch the resolution in her step, the hardness in her jaw, the murderous glint in her eye that also went unnoticed by all the family members and friends in attendance that night—and, to my shame, me. I’ve replayed the evening dozens of times in my head, and I’m sure of it: There was nothing out of the ordinary about her except that she was in exceptionally good spirits, which I’d attributed to her downing two flutes of champagne before the traditional first course of peach-shaped birthday buns had made its way to the banquet tables.

“Gwendolyn. Doll,” she’d whispered in my ear, giggling. She split a bun along its rose-tinted cleft, and dark lotus-seed paste oozed out.

“I always get a kick out of these,” she confided. “Don’t you think they look like blushing butts filled with …”

That set me giggling too. A fine way for two women in their early thirties to behave. Truth be told, I might have drunk my champagne too quickly as well.

You’d understand why, after sharing a sisterly moment such as this, I’d be baffled that Estella would want to kill me, or any of us, or, for that matter, herself. I think that’s why I’m not as angry as I probably should be. If she’d poisoned us all and spared her own life, it would have been unforgivable. But no, she wanted us dead and she wanted herself dead, and now only I am alive. If you can call it that.

It seems like ages ago that I learned I was the only survivor. It’s hard to keep track of time in my condition, so I can’t provide an exact hour or date, but it was after I’d woken up, gasping into emptiness, and screamed and screamed and nobody came. It was after the footsteps eventually arrived and, ignoring my cries for help, someone readjusted my body, tinkered 3 with the beeping thing at my side, and departed. It was an eternity after that—an endless cycle of being awake and terrified, of calling out in vain to whoever shifted me and rustled around my prone body, punctuated by bouts of exhausted sleep. It was even after I’d stopped calling out at all. (They couldn’t hear me. I finally came to terms with that.)

I found out what Estella had done only when two women came in and, while attending to me, began to talk to each other. I hadn’t heard voices for so long that my ears didn’t comprehend at first what they were saying. Gradually, words began to form out of the babble.

“… Estella Wirono. Granddaughter of the Chinese tycoon Irwan Sulinado. Put it in the shark’s fin soup. The footage was all over the news.”

“How many were poisoned?”

“Around three hundred.”

“How many survivors?”

“Only one.”

“A shame,” the second voice said sorrowfully.

Then they left me to my desolation.

Estella’s apology—her dying words—made sense after that. The chaos of the evening flooded back to me: The shrieking of the first victims as they began to choke and twitch, to retch and collapse, followed by a different sort of cry—the belated realization that one’s life is about to end. The hotel ballroom spinning madly. Guests staggering to their feet, trailing tablecloths in clenched fists. Wineglasses and plates of Peking duck crashing to the black-and-gold-carpeted floor. Gerry Sukamto trying to control unwieldy fingers long enough to dial a number on his mobile phone. Leonard’s mother convulsing on her knees, attempting to pray. Our cousin Marina crawling feebly toward one of the exits, sobbing with fear, the front of her evening gown drenched in vomit. The tiny bodies littered around the children’s table, their nannies desperately trying to wake them up. 4

I remember turning to my grandfather’s table and seeing the birthday boy lying limp in his chair. My stepgrandmother slumped in his lap, her powdered, chubby face crushed against his crotch.

That was when I lost myself in my own shaking and heaving. My cheek hit the ground. And there Estella lay as well, twitching, watching me, us watching each other. She reached for me, her arm creeping across the carpet so slowly it was difficult to tell it was moving at all. I tried to say something—what, I don’t know—but it dribbled from the corner of my lips in a weak groan.

Then she mouthed something. I didn’t understand. She mouthed it again: “Forgive me.”

What for? I wondered, before slipping into oblivion.

Now I know.

And as I said, I do—forgive her, I mean. I love her too much to do otherwise. But I still want to know why she did it. It’s only natural. I have little else to wonder about these days.

I didn’t anticipate ending like this. Who would? I’ve always known I would die someday, ideally after seventy, but before the point where I’d have to hire a nurse to spoon-feed me chicken congee and then clean my gums with a wet rag. The grim possibility of dying young also crossed my mind from time to time: a car accident, a plane crash, a terminal illness. But this—this hovering in blackness, this stretch of in-between, alive and dead and neither—this I never dreamed possible. Yet here I am.

Perhaps it’s just as well that I have so much time on my hands, even though I have no way of measuring its passing. And perhaps it’s also right that I have no visitors and, hence, no distractions: Everyone who would have taken the trouble to look in on me regularly is dead. It’s peaceful, though. A far cry from running Bagatelle, to be sure, but this way I can devote time to contemplating what Estella did, and coming to some understanding of it. In fact, the more I dwell on my circumstances, the more I 5realize the importance of the task before me—the task that only I am capable of carrying out. Who knew Estella more intimately than I? Who loved her more deeply? The answer to all this, if there is one, almost certainly lies with me. And call me crazy, but I’m positive it’s crouching in plain sight, waiting to be recognized for what it is.

2

“they’ve put me in charge of creating a photo slideshow for Opa’s birthday dinner.” The tone in which Estella delivered her announcement told me she wasn’t particularly enthused.

“Photos from the past,” she went on. “Opa as a boy. Opa as a teenager. Opa and Oma getting married. Opa and Oma and the kids. Significant events. Funny candid shots. That sort of thing.”

I shrugged. “It’s Opa’s eightieth. Very auspicious. We have a few weeks to go. Might as well pull out all the stops.”

“Did you say ‘we’?” she asked with a smile.

I corrected myself. “You all. I’d help, but Bagatelle can’t run itself.”

“I know. I figured you’d be too busy. They know I don’t have much to occupy me at Mutiara, so I don’t have an excuse.”

“You don’t want to do it. That’s a valid reason.”

“Too late.” She sighed. “Tante Margaret asked if I would, and I said yes. It’s fine. I really shouldn’t complain. It’s not that big a deal. Maybe it’ll be fun, digging through old photos and all that.”

“What else are you helping out with? I thought Tante Margaret was supposed to be in charge of organizing the whole thing.”

Tante Margaret wasn’t the oldest of our grandparents’ children, but that didn’t stop her from being the bossiest. Estella laughed. “Yes, she’s in charge, all right. She’s delegated everything: mostly to me and the cousins, though Ma’s pitching in too. Christina and Christopher are ordering the cake and party favors; Ma and I have arranged the venue and catering; Benedict, Jennifer, and Theresa are tackling the seating chart—Tante Margaret figured that three brains should be able to prevent social mismatches and hurt feelings. Marina’s taken care of the invitations, as 8I’m sure you’ve seen—engraved glass slabs in velvet boxes; what was she thinking? Even lazy Ricky’s playing a part; Om Benny’s agreed to fly him out from the US for the occasion. And now I’m supposed to see to entertainment. So far, it’s the slideshow and an emcee. Maybe a singer or a band …”

Just listening to all this made me immensely bored. I stifled a yawn. “So send Tante Margaret a text message and tell her you’ve done enough.”

“It’s a bit more complicated than that. Apparently, Tante Betty really wanted to do the slideshow, but Tante Margaret was worried she’d make a mess of it like she does everything else. So to spare Tante Betty’s feelings, she said that I had my heart set on it.”

I rolled my eyes. “As the older generation, you’d think they’d be more mature.”

“You know how it is with Tante Betty. She’s been touchy about everything since Opa handed Om Benny the reins.”

“The decision was made five years ago,” I observed. “You’d think she’d make her peace with it.”

Estella shrugged. “Frankly, I’m still not sure if she understands why Opa chose Om Benny and not her.”

Our aunt may have been the eldest child, but her knack for screwing everything up had made our uncle—the capable eldest son—the most logical heir to Opa’s throne. The choice had been a wise one. With Om Benny at the helm, Sulinado Group was doing better than ever. Our family conglomerate had bounced back with astonishing vigor from the monetary crisis that hit the country in late 1997. Synthetic textiles were what we were best known for, but our holdings in natural fabric manufacturing, agriculture, and natural resource extraction were now performing handsomely. Last year, we broke into Forbes Asia’s Top Sixty Richest Families in Indonesia list at number fifty-seven.

This was all in spite of Tante Betty. Her track record of failed projects 9was enough to make anyone’s hair stand on end: the cotton plantation, the oil refinery disaster, the debacle with the meatpacking plant …

Our coffees arrived. “It’s just a slideshow,” murmured Estella, sipping her cappuccino with a frown. “What a ridiculous thing to lie about.”

“What’s the alternative?” I chuckled. “Telling Tante Betty the truth? Has honesty ever been our family’s way?”

Ever so slightly, Estella’s shoulders slumped. I always forgot: Our family’s aversion to directness pained her more than it did me. As if to distract herself, she let her gaze drift to our surroundings, starting overhead with the high vaulted ceilings, their surfaces frescoed in blue sky, leafy branches, and yellow songbirds in midflight, and hung with chandeliers of rose crystal. From there, her eyes traveled down the walls—an honest vanilla hue—and across the pale parquet floor to the rest of the dining room: the ornately carved chairs upholstered in mossy velvet, the glass tables laid with cream-colored cloths and blue hydrangeas in squat crystal vases. There were barely any other diners. Prenoon brunches were a habit we’d picked up during our undergrad days in the US, and though the restaurant opened at 11 a.m. on weekends, few civilized members of our set ever ventured out before midday. I noticed Estella scanning for familiar faces nonetheless.

“No one we know,” I said to save her the trouble, and she breathed an infinitesimal sigh of relief. Estella was so conscious of familial responsibilities and social protocol, she found it difficult to relax completely around anyone of our acquaintance.

“The renovations look good,” she murmured, bringing her attention back to where we were sitting, by the floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking the iconic Hotel Indonesia roundabout outside. “Elegant. Tasteful. Not like before.”

I pretended to be astonished. “What, you didn’t like it? The purple leather? The Versace-print carpet? What’s wrong with a bit of Vegas charm?”10

Estella chuckled, which made me happy. I liked to see her laugh. “I don’t know what Eva was thinking,” she said. “And now she’s wasted eight months on redecorating, poor thing. Not to mention the money all this must have cost.”

“No one asked her to start her own business. She should have gotten it right the first time.”

“Not everyone’s as shrewd as you, Doll.”

“They should be. What’s the point of being Chinese in this country if you don’t live up to the stereotypes?”

Another snicker from Estella. I was on a roll.

I did have some sympathy for Eva, and not just because she was a former high school classmate and our cousin Christopher’s ex-girlfriend. The interior decorator had initially quoted her three months and half the price. Eight months was a long time to be closed—especially when you were paying sky-high rent for prime glass-front property. The privilege of looking down one’s nose at the dementedly happy bronze boy and girl atop the Welcome Monument didn’t come cheap. But the restaurant scene in Jakarta was so cutthroat that Eva couldn’t have afforded not to renovate Eva’s. (Yes, the restaurant was named after her—not that anyone was surprised.) The past few years had seen the luxury dining scene flare up like a rash, spreading through the capital at an alarming rate. Designer burger bars, edgy coffeehouses, and nouveau-style dumpling spots had popped up all over, not to mention chic restaurants specializing in street-vendor fare sans poor sanitation and at ten times the price. All were impeccably designed; all were staffed to the hilt with young, well-mannered, well-groomed waiters and waitresses; and all, to a certain extent, were interchangeable. Owning a restaurant was an expensive headache; to break even, you really had to stand out, keep it fresh, change the menu, change the chef, make the credit card discounts attractive, sponsor events, replace the décor and the furnishings at the slightest hint of wear or tear. Hence, the recent renovation 11of Eva’s. But any period of closure beyond four months was too long. Customers were like goats. They wandered off to graze elsewhere and forgot you ever existed. Eva’s face-lift had done wonders, but was it enough to make up for lost time?

I doubted it.

“Enough about the family. And Eva,” said Estella just as the waiter arrived with our lobster eggs Benedict. “Tell me what’s new with Bagatelle.”

“Not much since we met last Sunday.”

“Don’t be modest. There must be something exciting happening. Always is, isn’t there?”

I couldn’t help but beam. She was right. Bagatelle constantly had something new going on. It was part of the joy of starting one’s own business, and Estella’s eagerness for updates over our weekly brunch tête-à-têtes never failed to gratify me, especially since the rest of our family tried to pretend Bagatelle didn’t exist.

I told her about the progress our scientists had made on the newest version of our serum—a minor breakthrough, but a step forward nonetheless. And I described our two most promising ideas for next year’s autumn/winter lines. She listened as she did every Sunday—intently, brow furrowed, staring straight ahead, chewing and swallowing with relish as if my words heightened the pleasure of eating.

“Marvelous,” she murmured when she had exhausted my store of news. “I’m so proud of you, Doll. Bagatelle’s doing remarkable things.”

“What’s new with Mutiara?” I asked in return, a split second too late. I must have looked sheepish because she flashed me a reassuring smile.

“It’s okay, Doll. We both know nothing much happens there.”

True. The family had never intended for it to be an exciting holding. In fact, they’d never had any real ambitions for it at all. Sulinado Group had acquired it almost incidentally in early 1998, in the middle of the monetary 12crisis, when we should have been lying low like everybody else. Things were bleak across Asia, but in Indonesia, they were especially grim: The rupiah plummeted, and massive loan defaults tore the economy to shreds; the extended bloodbath on the Jakarta Stock Exchange was eventually followed by an actual bloodbath in May. Demonstrations were held; protesters were shot. Jakarta’s Chinatown was set ablaze, and Suharto finally stepped down.

Acquiring in that climate seemed like madness, so in hindsight it was clear why Opa was insistent. No one in the family had realized the extent of his condition. No one knew he had a condition at all. We mistook it for the same despotic obstinacy that had been his hallmark trait for as long as any of us could remember. And so, while all the other Chinese tycoon families tucked in their feelers and withdrew into their shells, Om Benny, acting on Opa’s orders, negotiated the purchase of the small silk-manufacturing company. Price wasn’t an issue: The Halim family was desperate to sell. Rumors raged nonetheless: How could Sulinado Group afford to acquire at a time like this? Everyone else was eyebrow-deep in foreign loans they couldn’t afford to pay off. What debts were we failing to service? What hidden offshore assets were we utilizing?

As it turned out, even in the early stages of Alzheimer’s, Opa proved cleverer than all of us. When the worst was over and the ruins had stopped smoldering; when chaos retreated back into the dark crannies where it could be ignored; when the president had been replaced, and replaced, and replaced yet again; when Indonesia’s economy began to stabilize and business recommenced in earnest, Mutiara lived up to its name. A pearl. Insignificant in size, yes, but with strong fundamentals and a consistently decent profit margin. It had a secret patented formula for weaving silk thread of varying thicknesses, producing an exceptionally durable yet very fine weave. More importantly, under the Halims’ control, it had somehow acquired a contract with the federal government to supply silk 13fabric for all state and tourism bureau needs. Still more importantly, the contract had, by some miracle, retained its validity through each change in administration.

Mutiara practically ran itself. And this had made it a perfect company for Estella to run upon her reentry into our family’s activities. Conveniently, the distant middle-aged relative we’d commissioned to oversee Mutiara had died suddenly of hemorrhagic dengue fever. It was the ideal situation for Estella, our mother reasoned to the rest of the clan. It would ease her into the business world without presenting her with any real difficulties. It was self-contained and uncomplicated in its operations. It was perfect.

But also boring. And if the arrangement had been an ideal one at first, especially given the tragedy of Leonard’s death a year and a half into her appointment (what other business would have plodded indifferently along despite months of neglect?), it was plain to see that Estella could do with more of a challenge.

More specifically, it was plain that Estella should be running Bagatelle with me. The glimmer in her eyes whenever I caught her up on company affairs, the flush of pride in her cheeks when I related its accomplishments—could anything have been more obvious? And yet here was the strange thing: No matter how many times I urged her to join me, she always refused.

“I’d only hold you back,” she’d say.

“No, you wouldn’t,” I’d insist.

“I mean it. If I come on board, I’ll ruin everything. You need complete freedom.”

“What the hell are you talking about? Come on, it’ll do you good.”

The debate and variations thereof would always end there, with her insisting that her noninvolvement was in Bagatelle’s best interest. She was happiest admiring my triumphs and living vicariously through my success.

“Anyway,” she would add, “I’m not like you. Never have been.”14

This was a lie. She was once. Before marriage. But it was impossible to change her mind.

Eventually, I stopped asking. I had my pride too. Bagatelle and Mutiara. They said so much about the different paths we had taken, even if we’d started out joined at the hip. Mine wound through a dark wood and up a solitary peak. Hers kept her confined to a garden maze walled by high hedges.

We’d just finished eating when the mobile phone at Estella’s elbow shivered. It was Tante Margaret. She was en route to Opa’s house and wanted to know if Estella could meet her there—so my sister could pick up the photos for the slideshow herself and save Tante Margaret the trouble of sending them later.

“That’s fine. See you soon,” said Estella, hanging up.

“Why do you always do that?” I asked.

“Do what?”

“They tell you to jump and you ask how high.”

“It’s called being accommodating.”

“Yeah, I know.” I shot her a mischievous grin. “I’m not into that. Not anymore.”

“True. You’re so unfilial these days, it’s positively unnatural.” She grinned back and shook her head. “It’s probably for the best.”

“It is. It keeps me from going crazy. You, on the other hand, they’re driving completely mad.”

She rolled her eyes. “Don’t exaggerate.”

“Well, you should set some boundaries.”

“A bit late for that now,” she retorted, a twang of bitterness in her voice.

I placed my hand over hers. “It’s not, you know. You’ve oriented yourself around family your whole life—us, Leonard, your in-laws. You’re only thirty-three. It’s not over yet.

“Join me at Bagatelle,” I almost said, pulling back in the nick of time. She’d rebuffed me already, too many times to count.15

“I know, I know,” she said with a sigh. “But it’s not easy to break away.”

“I don’t see why.”

“And that’s a good thing.” Then, in response to my puzzled look: “You not seeing, I mean. I think I have the opposite problem, Doll. I see too much. How things could be, you know? How things once were, how they might be again. It makes it hard to detach …”

I had no idea what she was talking about, but I made a decision. “I’m coming with you to Opa’s,” I declared.

“You don’t need to. I’m sure you have a lot of work to do.”

She was right. Two leaning towers of Bagatelle-related documents were waiting for me back at my apartment.

“It’s no trouble at all,” I said with a wave of my hand.

This was part of our routine, the dynamic we had settled into in recent years: Estella playing the protective sister, and me mirroring a similar protectiveness back at her, staying by her side in an effort to pry her from the family’s clutches. Consequently, I visited my parents and attended family gatherings far more than I would have otherwise. I wanted to remind her by my presence that she didn’t have to let others run her life.

“Well, if that’s what you really want,” she said. Her fingers hovered over her phone. “My car or yours? Or should we go separately?”

“We’ll go in your car,” I said. “I’ll tell my driver to meet us there.”

3

opa’s house both was and was not Opa’s house anymore. The home we remembered from our childhood had been capacious and cluttered—an abundance of high-ceilinged space portioned into an endless series of rooms and alcoves and passages, diminished only by the innumerable objects they housed. Our late grandmother had loved material possessions, innocently, as only a rich merchant’s daughter could.

When Oma was still alive, she would tell us grandchildren about exploring her father’s shipping warehouses as a little girl. Her father hadn’t seen the point of schooling his daughters, but he was generous with allowing them freedom when they were out of the house. As a child, she would spend whole days at the wharf, wandering amid piles of tobacco-leaf bundles and burlap sacks filled with coffee beans, sugar, and nutmeg. She would drape chains of tiny freshwater pearls around her neck and admire her reflection in propped-up panes of polished granite. She would press her cheeks against the cool of jade carvings and bury her face in folds of bright silk. Then, woozy from sniffing bottles of sandalwood oil and worn out from clambering up and down the rice-wine barrels stacked in pyramids, she would doze off. The laborers would find her atop an open flat of down pillows or curled up in a nest of packing straw. They would carefully convey her back to their boss’s office, her head resting against their bony brown shoulders.

“Feelings, ideas, philosophies—they’re reliable as the wind,” Oma would tell us grandchildren as she sat with us in the garden or as she pottered around the kitchen, baking cakes. These were her father’s wise words. She’d repeat them tenderly to us while tucking flowers behind our ears or depositing blobs of batter on our outstretched fingers and tongues. “Gold, 18on the other hand, and land. A roof over your head and food on the table. They keep you and your loved ones healthy and alive.”

Her father was right. It was material wealth that ensured his survival and that of his family during the Japanese Occupation, and afterward too, during the tumultuous years of the country’s struggle for independence from the Dutch. She recounted how her father had to draw often on those deep pockets of his: to purchase mercy from authorities, hoodlums, and anti-Chinese mobs; to keep beatings and insults to a minimum; to request that the plundering remain civilized and destruction restrained.

Having made it to adulthood on the strength of worldly goods, Oma lavished her possessions with affectionate gratitude. Although I can only speculate, perhaps it was why she didn’t object to her father orchestrating her marriage to Opa, who was then an industrious but penniless clerk in her father’s employ—an ambitious individual whose extraordinary shrewdness Oma’s father trusted to put his daughter’s inheritance to good use in order to provide for her and any offspring. I could imagine all too well young Oma marrying young Opa on compassionate grounds: How terrible for a promising young man to be poor, she must have thought. If she could furnish him with the means to achieve worldly success, then why shouldn’t they be happy together?

I don’t know what Oma’s taste in furnishings was like when she was younger, but the Oma of our childhood had a weakness for the heavy, ornate, and downright garish. Giving such objects space in her house was her version of doing good, like adopting stray animals. “I never saw anything like it,” she would say of each new acquisition once it had been delivered and unpacked. “It seemed a pity not to bring it home.”

Every room was furnished in dark mahoganies and teaks. Tables and chairs lurked everywhere; in the obvious places, of course—the dining room and the kitchen, the sitting room and the veranda—but also in corridors, like guests at an overcrowded party, and behind doors as if waiting to 19pounce. Less prolific, but still numerous, were the glass-paned cabinets and squat sideboards, covered in reliefs and edged with flourishes and spires. Bureaus and dressers of all sizes dominated the bedrooms, their drawers either bulging with rarely used bed linens and batiks, or practically empty save for random objects kept solely because there was no reason to throw them away—marbles, rubber bands, playing cards, screws.

The ornamental items were ten times as overwhelming, unable to hide behind any ostensibly practical purpose. Dark, ponderous paintings of stormy mountain ranges, brooding forests, and thundering horse herds—all framed in intricate gilt—covered every wall, interspersed with enormous Balinese friezes depicting ceremonial processions and battles. Sculptures in marble, wood, resin, jade, and stone, ranging from the size of bowling balls to the size of full-grown men, occupied whatever free space remained. Chinese lions, horses, and ingots; moonfaced Buddhas and serene Mother Marys; locally made replicas of famous classical and Renaissance art modified for modesty’s sake—Michelangelo’s David in a fig leaf and Venus de Milo in a toga with arms added. And there was the favorite of us grandchildren: a wooden statue of a smiling old man about half a meter tall with an enormous bulging head and a long trailing beard. In one hand he carried a knobbly walking stick, in the other a plump peach.

“He’s the god of long life,” Oma would tell us. “The peach represents immortality.” We were technically Christian, Oma’s father having converted from Buddhism in his youth. Still, Oma would insist, “We Chinese believe in him,” whenever we would ask, which was often because, like all children, we enjoyed hearing stories again and again.

“We Chinese …” The phrase betrayed both solidarity and distance: a faint but steady sense of kinship with an ancestral land and people whose customs and philosophies danced through our lives like shadows, rustled our daily and annual routines like delicate gusts of wind.

We grandchildren pretended we had an ancestor who looked like the 20statue, and developed a custom of rubbing the statue’s bald head when we passed by—our childish way of honoring his memory and ensuring our own longevity. By the time Estella and I had reached our teens, the bulbous head had been burnished black by the oils from all our hot, eager palms.

The statue was gone now, along with Oma’s other possessions: sold off or donated to charities and less well-to-do relations in order to make room for Opa’s second wife. “New Oma,” Estella and I called her. The renovation and redecoration of the old house constituted the one and only request she ever made. We resented her presumption at the time—Oma’s body was barely cold in the ground—but in hindsight, I suppose we couldn’t blame her. What bride, however docile in temperament, would want to spend the rest of her elderly husband’s life languishing among the bric-a-brac of her deceased predecessor? And so, as a marriage present, Opa had graciously consented to the complete remodeling of his home.