7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Pink Carnation

- Sprache: Englisch

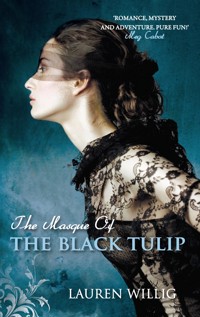

'But if modern manhood had let me down, at least the past boasted brighter specimens. To wit, the Scarlet Pimpernel, the Purple Gentian and the Pink Carnation, that dashing trio of spies who kept Napoleon in a froth of rage and the feminine population of England in another sort of froth entirely.' Modern-day student Eloise Kelly has achieved a great academic coup by unmasking the elusive spy the Pink Carnation, who saved England from Napoleon. But now she has a million questions about the Carnation's deadly nemesis, the Black Tulip. And she's pretty sure that her handsome on-again, off-again crush Colin Selwick has the answers somewhere in his family's archives. While searching through Lady Henrietta's old letters and diaries from 1803, Eloise stumbles across an old codebook and discovers something more exciting than she ever imagined: Henrietta and her old friend Miles Dorrington were on the trail of the Black Tulip and had every intention of stopping him in his endeavour to kill the Pink Carnation. But what they didn't know was that while they were trying to find the Tulip - and trying not to fall in love in the process - the Black Tulip was watching them.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 702

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Praise for the novels ofLAUREN WILLIG

The Masque of the Black Tulip

‘Delightful’

Kirkus Reviews

‘Willig picks up where she left readers breathlessly hanging… Many more will delight in this easy-to-read romp and line up for the next instalment’

Publishers Weekly

‘What’s most delicious about Willig’s novels is that the damsels of 1803 bravely put it all on the line for love and country’

The Detroit Free Press

‘Studded with clever literary and historical nuggets… a charming historical/contemporary romance [that] moves back and forth in time’

USA Today

‘Willig has great fun with the conventions of the genre, throwing obstacles between her lovers at every opportunity’

The Boston Globe

‘Enchanting’

Midwest Book Review

The Secret History of the Pink Carnation

‘A deftly hilarious, sexy novel’

Eloisa James, author of Taming of the Duke

‘A merry romp with never a dull moment! A fun read’ Mary Balogh, New York Times bestselling author of

The Secret Pearl

‘Has it all: romance, mystery, and adventure. Pure fun!’ Meg Cabot, author of Queen of Babble

‘A historical novel with a modern twist. I loved the way Willig dips back and forth from Eloise’s love affair and her swish parties to the Purple Gentian and of course the lovely, feisty Amy. The unmasking of the Pink Carnation is a real surprise’ Mina Ford, author of My Fake Wedding

‘Swashbuckling… Willig has an ear for quick wit and an eye for detail. Her fiction debut is chock-full of romance, sexual tension, espionage, adventure, and humour’

Library Journal

‘A juicy mystery – chick lit never had it so good!’

Complete Woman

‘Relentlessly effervescent prose…a sexy, smirking, determined-to-charm historical romance debut’

Kirkus Reviews

The Masque of theBlack Tulip

LAUREN WILLIG

To Brooke, paragon among little sisters, between whom and Henrietta

Contents

PraiseTitle PageDedicationChapter OneChapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter SixChapter SevenChapter EightChapter Nine Chapter Ten Chapter Eleven Chapter Twelve Chapter ThirteenChapter FourteenChapter FifteenChapter SixteenChapter SeventeenChapter EighteenChapter NineteenChapter TwentyChapter Twenty-OneChapter Twenty-TwoChapter Twenty-ThreeChapter Twenty-FourChapter Twenty-FiveChapter Twenty-SixChapter Twenty-SevenChapter Twenty-EightChapter Twenty-NineChapter ThirtyChapter Thirty-OneChapter Thirty-TwoChapter Thirty-ThreeChapter Thirty-Four Chapter Thirty-FiveChapter Thirty-SixChapter Thirty-SevenChapter Thirty-EightAcknowledgmentsHistorical NoteThe Secret History of the Pink CarnationThe Masque of the Black TulipThe Deception of the Emerald RingThe Seduction of the Crimson RoseThe Temptation of the Night JasmineAbout the AuthorBy the Same AuthorCopyright

Chapter One

London, England, 2003

I bit my lip on an ‘Are we there yet?’

If ever silence was the better part of valour, now was the time. Palpable waves of annoyance emerged from the man beside me, thick enough to constitute an extra presence in the car.

Under the guise of inspecting my fingernails, I snuck another glance sideways at my car mate. From that level, all I could see was a pair of hands tense on the steering wheel. They were tanned and callused against the brown corduroy cuffs of his jacket, with a fine dusting of blond hairs outlined by the late-afternoon sun, and the white scar of an old cut showing against the darker skin on his left hand. Large hands. Capable hands. Right now he was probably imagining them clasped around my neck.

And I don’t mean in an amorous embrace.

I had not been part of Mr Colin Selwick’s weekend plans. I was the fly in his ointment, the rain on his parade. The fact that it was a very attractive parade and that I was very single at the moment was entirely beside the point.

If you’re wondering what I was doing in a car bound for parts unknown with a relative stranger who would have liked nothing better than to drop me in a ditch – well, I’d like to say, so was I. But I knew exactly what I was doing. It all came down to, in a word, archives.

Admittedly, archives aren’t usually a thing to set one’s blood pounding, but they do when you’re a fifth-year graduate student in pursuit of a dissertation, and your advisor has begun making ominous noises about conferences and job talks and the nasty things that happen to attenuated graduate students who haven’t produced a pile of paper by their tenth year. From what I understand, they’re quietly shuffled out of the Harvard history department by dead of night and fed to a relentless horde of academic-eating crocodiles. Or they wind up at law school. Either way, the point was clear. I had to rack up some primary sources, and I had to do it soon, before the crocodiles started getting restless.

There was a teensy little added incentive involved. The incentive had dark hair and brown eyes, and occupied an assistant professorship in the Gov department. His name was Grant.

I have, I realise, left out his most notable characteristic. He was a cheating slime. I say that entirely dispassionately. Anyone would agree that smooching a first-year grad student – during my department’s Christmas party, which he attended at my invitation – is indisputable evidence of cheating slimedom.

All in all, there had never been a better time to conduct research abroad.

I didn’t include the bit about Grant in my grant application. There is a certain amount of irony in that, isn’t there? Grant… grant… The fact that I found that grimly amusing just goes to show the pathetic state to which I had been reduced.

But if modern manhood had let me down, at least the past boasted brighter specimens. To wit, the Scarlet Pimpernel, the Purple Gentian, and the Pink Carnation, that dashing trio of spies who kept Napoleon in a froth of rage and the feminine population of England in another sort of froth entirely.

Of course, when I presented my grant proposal to my advisor, I left out any references to evil exes and the aesthetic properties of knee breeches. Instead, I spoke seriously about the impact of England’s aristocratic agents on the conduct of the war with France, their influence on parliamentary politics, and the deeper cultural implications of espionage as a gendered construct.

But my real mission had little to do with Parliament or even the Pimpernel. I was after the Pink Carnation, the one spy who had never been unmasked. The Scarlet Pimpernel, immortalised by the Baroness Orczy, was known the world over as Sir Percy Blakeney, Baronet, possessor of a wide array of quizzing glasses and the most impeccably tied cravat in London. His less-known successor, the Purple Gentian, had carried on quite successfully for a number of years until he, too, had been undone by love, and blazoned before the international press as Lord Richard Selwick, dashing rake about town. The Pink Carnation remained a mystery, to the French and scholars alike.

But not to me.

I wish I could boast that I had cracked a code, or deciphered an ancient text, or tracked an incomprehensible map to a hidden cache of papers. In fact, it was pure serendipity, disguised in the form of an elderly descendant of the Purple Gentian. Mrs Selwick-Alderly had made me free of both her home and a vast collection of family papers. She didn’t even ask for my firstborn child in return, which I understand is frequently the case with fairy godmothers in these sorts of situations.

The only drawback to this felicitous arrangement was Mrs Selwick-Alderly’s nephew, current owner of Selwick Hall, and self-appointed guardian of the family heritage. His name? Mr Colin Selwick.

Yes, that Colin Selwick.

To say that Colin had been less than pleased at seeing me going through his aunt’s papers would have been rather like saying that Henry VIII didn’t have much luck with matrimony. If decapitations were still considered a valid way of settling domestic problems, my head would have been the first on his block.

Under the influence of either my charming personality or a stern talking-to from his aunt (I suspected the latter), Colin had begun to thaw to nearly human behaviour. I must say, it was an impressive process. When he wasn’t snapping insults at me, he had the sort of crinkly eyed smile that made movie theatres full of women heave a collective sigh. If you liked the big, blond, sporting type. Personally, I went more for tall, dark, and intellectual myself.

Not that it was an issue. Any rapport we might have developed had rapidly disintegrated when Mrs Selwick-Alderly suggested that Colin give me access to the family archives at Selwick Hall for the weekend. Suggested is putting it a bit mildly. Railroaded would be more to the point. The traffic gods hadn’t done anything to help the situation. I had given up trying to make small talk somewhere along the A-23, where there had been an epic traffic jam involving a stalled-out car, an overturned lorry, and a tow truck that reached the scene of the crime and promptly broke down out of sympathy.

I cast another surreptitious glance in Colin’s direction.

‘Would you stop looking at me like you’re Red Riding Hood and I’m the wolf?’

Maybe it hadn’t been all that surreptitious.

‘Why, Grandmother, what big archives you have?’ As an attempt at humour, it lacked something, but given that it was the first time my vocal cords had had any exercise over the past two hours, I was reasonably pleased with the result.

‘Do you ever think about anything else?’ asked Colin. It was the sort of question that from anyone else I would have construed as an invitation to flirtation. From Colin, it just sounded exasperated.

‘Not with a dissertation deadline looming.’

‘We,’ he pronounced ominously, ‘still have to discuss what exactly is going to go into your dissertation.’

‘Mmmph,’ I said enigmatically. He had already made his feelings on that clear, and I saw no point in giving him the opportunity to reiterate them. Less discussed, more easily ignored. It was time to change the subject. ‘Wine gum?’

Colin emitted a choked noise that might have been a laugh if allowed to grow up. His eyes met mine in the rear-view mirror in an expression that might have been, ‘I like your nerve,’ or might have been ‘Oh, God, who let this lunatic loose in my car and where can I dump her?’

All he actually said was ‘Thanks,’ and held out one large hand, palm up.

In the spirit of entente, I passed over the orange and flipped a red one into his palm. Popping the despised orange into my own mouth, I sucked it meditatively, trying to think of a conversational gambit that wouldn’t touch on forbidden topics.

Colin did it for me. ‘If you look to your left,’ he said, ‘you should be able to see the house.’

I caught a brief, tantalising glimpse of crenellated battlements looming above the trees like a lost set from a Frankenstein movie before the car swung around a curve, bringing us into full view of the house. Built of a creamy-coloured stone, the house was what the papers might call ‘a stately pile,’ a square central section with the usual classical adornments, with a smaller wing sticking out on either side of the central block. It was a perfectly normal eighteenth-century gentleman’s residence, and exactly what one would expect the Purple Gentian to have lived in. There were no battlements.

The car scraped to a halt in the circle of gravel that fronted the entrance. Not waiting to see if he was going to open the door for me, I grabbed the oversized tote in which I had crammed two days’ worth of weekend wear, and scrambled out of the door of the car before Colin could reach it, determined to be as obliging as possible.

My heels crunched on the gravel as I followed Colin to the house, the little pebbles doing nasty things to the leather of my stacked loafers. One would have expected assorted staff to be lining the halls, but instead the front hall was decidedly empty as Colin stepped aside to allow me in. The door snapped shut with a distinctly ominous clang.

‘You can just take me to the library and then forget all about me,’ I suggested helpfully. ‘You won’t even know I’m here.’

‘Were you planning to sleep in the library?’ he enquired with some amusement, his eyes going to the overnight bag on my arm.

‘Um…I hadn’t really thought about it. I can sleep wherever.’

‘Indeed.’

I could feel my face flaring with light like a high school fire alarm, and rapidly tried to ameliorate the situation. ‘What I mean is, I’m easy.’

Urgh. Worser and worser, as Alice might say. There are times when I shouldn’t be allowed out of the house without a muzzle.

‘Easy to have as a houseguest, I mean,’ I specified in a strangled voice, hoisting my bag farther up on my shoulder.

‘I think the hospitality of Selwick Hall can stretch to providing you a bed,’ commented Colin dryly, leading the way up a flight of stairs tucked away to one side of the hall.

‘That’s nice to know. Very generous of you.’

‘Too much hassle clearing out the dungeons,’ explained Colin, twisting open a door not far from the landing, revealing a medium-sized room possessed of a dark four-poster bed. The walls were dark green, patterned with gold-tinted animals that looked like either dragons or gryphons, squatting on their haunches, stylised wings poking into the forequarters of the next beast over. He stepped aside to let me precede him.

Dumping my bag onto the bed, I turned back around to face Colin, who was still propping up the door. I shoved my hair out of my eyes. ‘Thanks. Really. It’s really nice of you to have me here.’

Colin didn’t mouth any of the usual platitudes about it being no problem, or being delighted to have me. Instead, he tipped his head in the direction of the hall and said, ‘The loo is two doors down to your left, the hot water tends to cut out after ten minutes, and the flush needs to be jiggled three times before it settles.’

‘Right,’ I said. He got points for honesty, at least. ‘Got it. Loo on the left, two jiggles.’

‘Three jiggles,’ Colin corrected.

‘Three,’ I repeated firmly, as though I was actually going to remember. I trailed along after Colin down the hallway.

‘Eloise?’ A few yards ahead, Colin was holding open a door at the end of the hall.

‘Sorry!’ I scurried down the length of the hall to catch up, plunging breathlessly through the doorway. Crossing my arms over my chest, I said, a little too heartily, ‘So this is the library.’

There certainly couldn’t be any doubt on that score; never had a room so resembled popular preconception. The walls were panelled in rich, dark wood, although the finish had worn off the edges in spots where books had scraped against the wood in passing one too many times. A whimsical iron staircase curved to the balcony, the steps narrowing into pie-shaped wedges that promised a broken neck to the unwary. I tilted my head back, dizzied by the sheer number of books, row upon row, more than the most devoted bibliophile could hope to consume in a lifetime of reading. In one corner, a pile of crumbling paperbacks – James Bond, I noticed, squinting sideways, in splashy seventies covers – struck a slightly incongruous note. I spotted a mouldering pile of Country Life cheek by jowl with a complete set of Trevelyan’s History of England in the original Victorian bindings. The air was rich with the smell of decaying paper and old leather bindings.

Downstairs, where I stood with Colin, the shelves made way for four tall windows, two to the east and two to the north, all hung with rich red draperies checked with blue, in the obverse of the red-flecked blue carpet. On the west wall, the bookshelves surrendered pride of place to a massive fireplace, topped with a carved hood to make Ivanhoe proud, and large enough to roast a serf.

In short, the library was a Gothic fantasy.

My face fell.

‘It’s not original.’

‘No, you poor innocent,’ said Colin. ‘The entire house was gutted not long before the turn of the century. The last century,’ he added pointedly.

‘Gutted?’ I bleated.

Oh, fine, I know it’s silly, but I had harboured romantic images of walking where the Purple Gentian had walked, sitting at the desk where he had penned those hasty notes upon which the fate of the kingdom rested, viewing the kitchen where his meals had been prepared… I made a disgusted face at myself. At this rate, I was only one step away from going through the Purple Gentian’s garbage, hugging his discarded port bottles to my palpitating bosom.

‘Gutted,’ repeated Colin firmly.

‘The floor plan?’ I asked pathetically.

‘Entirely altered.’

‘Damn.’

The laugh lines at the corners of his mouth deepened.

‘I mean,’ I prevaricated, ‘what a shame for posterity.’

Colin raised an eyebrow. ‘It’s considered one of the great examples of the arts and crafts movement. Most of the wallpaper and drapes were designed by William Morris, and the old nursery has fireplace tiles by Burne-Jones.’

‘The Pre-Raphaelites are distinctly overrated,’ I said bitterly.

Colin strolled over to the window, hands behind his back. ‘The gardens haven’t been changed. You can always go for a stroll around the grounds if the Victorians begin to overwhelm you.’

‘That won’t be necessary,’ I said, with as much dignity as I could muster. ‘All I need is your archives.’

‘Right,’ said Colin briskly, turning away from the window. ‘Let’s get you set, then, shall we?’

‘Do you have a muniments room?’ I asked, tagging along after him.

‘Nothing so grand.’ Colin strode straight towards one of the bookcases, causing me a momentary flutter of alarm. The books on the shelf certainly looked elderly – at least, if the dust on the spines was anything to go by – but they were all books. Printed matter. When Mrs Selwick-Alderly had said there were records at Selwick Hall, she hadn’t specified what kind of records. For all I knew, she might well have meant one of those dreadful Victorian vanity publications compiled from ‘missing’ records, titled ‘Some Documents Formerly in the Possession of the Selwick Family but Tragically Dropped Down a Privy Last Year.’ They never cited their sources, and they tended to excerpt only those bits they found interesting, cutting out anything that might not redound to the greater credit of the ancestry.

But Colin bypassed the rows of leather-bound books. Instead, he hunkered down in front of the elaborately carved mahogany wainscoting that ran, knee-high, around the length of the room, in a movement as smooth as it was unexpected.

‘Hunh?’ I nearly tripped over him, stopping so short that one of my knees banged into his shoulder blades. Grabbing the edge of a bookshelf to steady myself, I stared down in bewilderment as Colin bent over the wooden panelling, his head blocking my view of whatever it was he was doing. All I could see was sun-streaked hair, darker at the roots as the effects of summer faded, and an expanse of bent back, broad and muscled beneath an oxford-cloth shirt. A whiff of shampoo, recently applied, wafted up against the stuffy smells of closed rooms, old books, and decaying leather.

I couldn’t see what he was doing, but he must have turned some sort of latch, because the wainscoting opened out, the joint cleverly disguised by the pattern of the wood. Now that I knew what to look for, there was nothing mysterious about it at all. Glancing around the room, I could see that the wainscoting was flush with the edge of the shelves above, leaving a space about two feet deep unaccounted for.

‘These are all cupboards,’ Colin explained briefly, swinging easily to his feet beside me.

‘Of course,’ I said, as if I had known all along, and never harboured alarming images of being forced to read late-Victorian transcriptions.

One thing was sure: I need have no worries about having to entertain myself with back issues of Punch. There were piles of heavy folios bound in marbled endpapers, a scattering of flat cardboard envelopes looped shut with thin spools of twine, and whole regiments of the pale grey acid-free boxes used to hold loose documents.

‘How could you have kept this to yourself all these years?’ I exclaimed, falling to my knees in front of the cupboard.

‘Very easily,’ said Colin dryly.

I flapped a dismissive hand in his general direction, without interrupting my perusal. I scooted forward to see better, tilting my head sideways to try to read the typed labels someone had glued to the spines a long time ago, if their yellowed state and the shape of the letters were anything to go by. The documents seemed to be roughly organised by person and date. The ancient labels said things like LORD RICHARD SELWICK (1776–1841), CORRESPONDENCE, MISCELLANEOUS, 1801–1802, or SELWICK HALL, HOUSEHOLD ACCOUNTS, 1800–1806. Bypassing the household accounts, I kept looking. I reached for a folio at random, drawing it carefully out from its place next to a little pocket-sized book bound in worn red leather.

‘I’ll leave you to it, shall I?’ said Colin.

‘Mmm-hmm.’

The folio was a type I recognised from the British Library, older documents pasted onto the leaves of a large blank book, with annotations around the edges in a much later hand. On the first page, an Edwardian hand had written in slanting script, ‘Correspondence of Lady Henrietta Selwick, 1801–1803.’

‘Dinner in an hour?’

‘Mmm-hmm.’

I flipped deliberately towards the back, scanning salutations and dates. I was looking for references to two things: the Pink Carnation, or the school for spies founded by the Purple Gentian and his wife, after necessity forced them to abandon active duty. Neither the Pink Carnation nor the spy school had been in operation much before May of 1803. Wedging the volume back into place, I jiggled the next one out from underneath, hoping that they had been stacked in some sort of chronological order.

‘Arsenic with a side of cyanide?’

‘Mmm-hmm.’

They had. The next folio down comprised Lady Henrietta’s correspondence from March of 1803 to the following November. Perfect.

On the edge of my consciousness, I heard the library door close.

Scooting backwards, I sat down heavily on the floor next to the open cupboard, the folio splayed open in my lap. Nestled in the middle of Henrietta’s correspondence was a letter in a different hand. Where Henrietta’s script was round, with loopy letters and the occasional flourish, this writing was regular enough to be a computer simulation of script. Without the aid of technological enhancement, the writing spoke of an orderly hand, and an even more orderly mind. More important, I knew that handwriting. I had seen it in Mrs Selwick-Alderly’s collection, between Amy Balcourt’s sloppy scrawl and Lord Richard’s emphatic hand. I didn’t even have to flip to the signature on the following page to know who had penned it, but I did, anyway. ‘Your affectionate cousin, Jane.’

There are any number of Janes in history, most of them as gentle and unassuming as their name. Lady Jane Grey, the ill-fated seven-day queen of England. Jane Austen, the sweet-faced authoress, lionised by English majors and the BBC costume-drama-watching set.

And then there was Miss Jane Wooliston, better known as the Pink Carnation.

I clutched the binding of the folio as though it might scuttle away if I loosened my grip, refraining from making squealing noises of delight. Colin probably already thought I was a madwoman, without my providing him any additional proof. But I was squealing inside. As far as the rest of the historical community was concerned (I indulged in a bit of personal gloating), the only surviving references to the Pink Carnation were mentions in newspapers of the period, not exactly the most reliable report. Indeed, there were even scholars who opined that the Pink Carnation did not in fact exist, that the escapades attributed to the mythical flower figure over a ten-year period – stealing a shipment of gold from under Bonaparte’s nose, burning down a French boot factory, spiriting away a convoy of munitions in Portugal during the Peninsular War, to name just a few – had been the work of a number of unrelated actors. The Pink Carnation, they insisted, was something like Robin Hood, a useful myth, perpetuated to keep people’s morale up during the grim days of the Napoleonic Wars, when England stood staunchly alone as the rest of Europe tumbled under Napoleon’s sway.

Weren’t they in for a surprise!

I knew who the Pink Carnation was, thanks to Mrs Selwick-Alderly. But I needed more. I needed to be able to link Jane Wooliston to the events attributed to the Pink Carnation by the news sheets, to provide concrete proof that the Pink Carnation had not only existed, but had been continuously in operation throughout that period.

The letter in my lap was an excellent start. A reference to the Pink Carnation would have been good. A letter from the Pink Carnation herself was even better.

Greedily, I skimmed the first few lines.

‘Dearest Cousin, Paris has been a whirl of gaiety since last I wrote, with scarcely a moment to rest between engagements…’

Chapter Two

Venetian Breakfast: a midnight excursion of a clandestine kind

– from the Personal Codebook of the Pink Carnation

‘…Yesterday, I attended a Venetian breakfast at the home of a gentleman very closely connected to the Consul. He was all that was amiable.’

In the morning room at Uppington House, Lady Henrietta Selwick checked the level of liquid in her teacup, positioned a little red book on the cushion next to her, and curled up against the arm of her favourite settee.

Under her elbow, the fabric was beginning to snag and fray; suspicious tea-coloured splotches marred the white-and-yellow-striped silk, and worn patches farther down the settee testified to the fact that the two slippered feet that currently occupied them had been there before. The morning room was usually the province of the lady of the house, but Lady Uppington, who lacked the capacity for sitting in one place longer than it took to deliver a pithy epigram, had long since ceded the sunny room to Henrietta, who used it as her receiving room, her library (the real library having the unfortunate defect of being too dark to actually read in), and her study. Haloed in the late-morning sunlight, it was a pleasant, peaceful room, a room for innocent daydreams and restrained tea parties.

At the moment, it was a hub for international espionage.

On the little yellow-and-white settee rested secrets for which Bonaparte’s most talented agents would have given their eye teeth – or their eyes, for that matter, if that wouldn’t have got in the way of actually reading the contents of the little red book.

Henrietta spread Jane’s latest letter out on her muslin-clad lap. Even if a French operative did happen to be peering through the window, Henrietta knew just what he would see: a serene young lady (Henrietta hastily pushed a stray wisp of hair back into the Grecian-style bun on the top of her head) daydreaming over her correspondence and her diary. It was enough to put a spy to sleep, which was precisely why Henrietta had suggested the plan to Jane in the first place.

For seven long years, Henrietta had been angling to be included in the war effort. It didn’t seem quite fair that her brother got to be written up in the illustrated newsletters as ‘that glamorous figure of shadow, that thorn in the side of France, that silent saviour men know only as the Purple Gentian,’ while Henrietta was stuck being the glamorous shadow’s pesky younger sister. As she had pointed out to her mother the year she turned thirteen – the year that Richard joined the League of the Scarlet Pimpernel – she was as smart as Richard, she was as creative as Richard, and she was certainly a great deal stealthier than Richard.

Unfortunately, she was also, as her mother reminded her, a good deal younger than Richard. Seven years younger, to be precise.

‘Oh, bleargh,’ said Henrietta, since there was really nothing she could say in response to that, and Henrietta wasn’t the sort who liked being without something to say.

Lady Uppington looked at her sympathetically. ‘We’ll discuss it when you’re older.’

‘Juliet was married when she was thirteen, you know,’ protested Henrietta.

‘Yes, and look what happened to her,’ replied Lady Uppington.

By the time she was fifteen, Henrietta decided she had waited quite long enough. She put her case to the League of the Scarlet Pimpernel in her best imitation of Portia’s courtroom speech. The gentlemen of the League were not moved by her musings on the quality of mercy, nor were they swayed by her arguments that an intrepid young girl could wriggle in where a full-grown man would get stuck in the window frame.

Sir Percy looked sternly at her through his quizzing glass. ‘We’ll discuss it—’

‘I know, I know,’ Henrietta said wearily, ‘when I’m older.’

She didn’t have any more success when Sir Percy retired and Richard began cutting a wide swath through French prisons and English news sheets as the Purple Gentian. Richard, being her older brother, was a great deal less diplomatic than Sir Percy had been. He didn’t even make the obligatory reference to her age.

‘Have you run mad?’ he asked, running a black-gloved hand agitatedly through his blond hair. ‘Do you know what Mother would do to me if I so much as let you near a French prison?’

‘Ah, but does Mama need to know?’ suggested Henrietta cunningly.

Richard gave her another ‘Have you gone completely and utterly insane?’ look.

‘If Mother is not told, she will find out. And when she finds out,’ he gritted out, ‘she will dismember me.’

‘Surely, it’s not as bad as—’

‘Into hundreds and hundreds of tiny pieces.’

Henrietta had persisted for a bit, but since all she could get out of her brother was incoherent mumbles about his head being stuck up on the gates of Uppington Hall, his hindquarters being fed to the dogs, and his heart and liver being served up on a platter in the dining room, she gave up, and went off to do some muttering of her own about overbearing older brothers who thought they knew everything just because they had a five-page spread on their exploits in the Kentish Crier.

Appealing to her parents proved equally ineffectual. After Richard had been inconsiderate enough to go and get himself captured by the Ministry of Police, Lady Uppington had become positively unreasonable on the subject of spying. Henrietta’s requests were met with ‘No. Absolutely not. Out of the question, young lady,’ and even one memorable ‘There are still nunneries in England.’

Henrietta wasn’t entirely certain that her mother was right about that – there had been a Reformation, and a fairly thorough one, at that – but she had no desire to test the point. Besides, she had heard all about the Ministry of Police’s torture chamber in lurid detail from her new sister-in-law, Amy, and rather doubted she would enjoy their hospitality any more than Richard had.

But when one has been angling for something for seven years, it is rather hard to let go of the notion just like that. So when Amy’s cousin, Jane Wooliston, otherwise known as the Pink Carnation, happened to mention that she was having trouble getting reports back to the War Office because her couriers had an irritating habit of being murdered en route, Henrietta was only too happy to offer her assistance.

It was, Henrietta assured her conscience, a safe enough assignment that even her mother couldn’t possibly find fault with it, or start looking about for England’s last operational nunnery. It wasn’t Henrietta who would be scurrying through the dark alleyways of Paris, or riding hell-for-leather down rutted French roads in a desperate attempt to reach the coast. All she had to do was sit in the morning room at Uppington House, and maintain a perfectly normal-sounding correspondence with Jane about balls, dresses, and other topics guaranteed to bore French agents to tears.

Normal-sounding was the key. While in London for Amy and Richard’s wedding, Jane had spent a few days at her writing table, scribbling in a little red book. When she had finally emerged, she had presented Henrietta with a complete lexicon of absolutely everyday terms with far-from-everyday meanings.

Ever since Jane’s return to Paris two weeks ago, the plan had proved tremendously effective. Even the most hardened French operative could find nothing to quicken his suspicion in an exchange about the relative merits of flowers as opposed to bows as trimming for an evening gown, and the eyes of the most determined interceptor of English letters were sure to glaze when confronted with a five-page-long description of yesterday’s Venetian breakfast at Viscountess of Loring’s Paris residence.

Little did they realize that ‘Venetian breakfast’ was code for a late-night raid on the secret files of the Ministry of Police. Breakfast, after all, was supposed to take place early in the morning, and thus made a perfect analogue for ‘dead of night.’ As for Venetian…well, Delaroche’s filing system was as complex and secretive as the workings of the Venetian Signoria at the height of their Renaissance decadence.

Which brought Henrietta back to the letter at hand.

Jane had begun it ‘My very dearest Henrietta,’ a salutation that signified news of the utmost importance. Henrietta sat up straighter on the settee. Jane had been rooting about in someone’s study – the letter didn’t specify whose – and he had been all amiability, which meant that whatever papers Jane had meant to find had been easily found, and Jane had been unmolested in her search.

‘I have sent word to our great-uncle Archibald in Aberdeen’ – that was William Wickham at the War Office – ‘in care of Cousin Ned.’ Henrietta reached for the red morocco-covered codebook. ‘Cousin’ she had seen before; it translated quite simply as ‘courier.’ Henrietta reached the proper page in the codebook. ‘See under Ned, Cousin,’ instructed Jane. Mumbling a bit to herself about people with regrettably organised minds, Henrietta flipped forward to the Ns. ‘Ned, Cousin: a professional courier in the service of the League.’

Henrietta scowled at the little red book. Jane had sent her all the way to the Ns for that?

‘Given dear Ned’s propensity for falling in with the wrong sort of company,’ Jane continued, ‘I deeply fear he shall be so busy carousing and roistering about, he shall neglect to fulfil my little commission.’

Having achieved some notion of the way Jane’s mind worked, Henrietta flipped straight to the Cs, indulging in a small smirk as she beheld, ‘Company, wrong sort of,’ just beneath, ‘Company, best sort of,’ ‘Company, better not sought out,’ and ‘Company, convivial.’ Her smirk faded somewhat at the knowledge that ‘Company, wrong sort of’ signified: ‘a murderous band of French agents, employed for the primary purpose of eliminating English intelligence officers.’ Poor Cousin Ned. Likewise, ‘Carousing,’ a page back, had nothing to do with bacchanalian excesses, but instead meant ‘engaged in a life-or-death struggle with Bonaparte’s minions,’ an activity that sounded highly unpleasant.

‘But what is it?’ Henrietta muttered at the unresponsive piece of paper in her hands. Had Jane discovered new plans for the invasion of England? A design for the destruction of the English fleet? It might even, mused Henrietta, be another attempt to assassinate King George. Her brother had foiled two of those, but the French kept on trying. At least, they assumed it was the French, and not the Prince of Wales trying to get back at his father for forcing him to marry Caroline of Brunswick, who bore the dubious distinction of being the smelliest princess in Europe.

‘Do tell dear Uncle Archibald,’ continued Jane tantalisingly, after a long and tedious description of the gowns worn by half the women at the imaginary Venetian breakfast, ‘that a new horrid novel is even now on its way to Hatchards and should be arrived by the time you receive this epistle!’

Henrietta thumbed through Jane’s little book. ‘Horrid Novel: a master spy of the most devious kind.’

There was no entry for Hatchards, but since Hatchards bookshop was in Piccadilly, Henrietta had no doubt that Jane was trying to signify that this master spy was even now somewhere in the vicinity of London.

‘I assure you, my dearest Henrietta, this is quite the horridest of horrid novels; I have never encountered one horrider. It is really quite, quite horrid.’

Henrietta didn’t need the codebook to grasp the import of those lines.

That there were French spies in London wasn’t terribly shocking; the city was riddled with them. The papers had trumpeted the capture of a group of French spies masquerading as cravat merchants just the week before last.

Richard, in one of his last acts as the Purple Gentian, had uprooted the better part of Delaroche’s personal spy network, a varied group that had comprised scullery maids, pugilists, courtesans, and even someone posing as a minor member of the royal family. (Queen Charlotte and King George had so many children that it was nearly impossible to keep track of who was who.) There were spies reporting to Delaroche, spies answering to Fouché, spies for the exiled Bourbon monarchy, and spies who spied for the sake of spying and would offer their information to whoever offered them the largest pile of coin.

This spy, clearly, was something out of the ordinary.

Sitting there, with the letter crumpled in her lap, Henrietta was struck by an idea, an idea that made the corners of her lips curl up, and put a mischievous sparkle into her hazel eyes. What if… No. Henrietta shook her head. She shouldn’t.

But what if…

The idea poked and prodded at her with the insistence of a hungry ferret. Henrietta gazed raptly into space. The curl at the corners of her lips turned into a full-blown grin.

What if she were to unmask this particularly horrid spy herself?

Henrietta leant against the side of the settee, propping her chin on her wrist. What harm could it do if there were an extra pair of eyes and ears devoted to the task? It wasn’t as though she would do anything foolish, like hide the information from the War Office and set out on the task alone. Henrietta, a great devotee of sensational novels, had always maintained the liveliest contempt for those pea-witted heroines who refused to go to the proper authorities and instead insisted on hiding vital information until the villain had chased them through subterranean passageways to the edge of a storm-racked cliff.

No, Henrietta would do exactly as Jane had requested, and deliver the decoded letter to Wickham at the War Office via her contact in the ribbon shop on Bond Street. The point, after all, was to apprehend whoever it was as quickly as possible, and Henrietta knew that the War Office’s resources were far more extensive than hers, sister to a spy though she might be.

All the same, what a coup it would be if she could find the spy first! Certain people – certain people by the surname of Selwick, to be precise – would have a great big ‘I told you so’ coming to them.

There was one slight shadow marring the shining landscape of her daydream. She didn’t have the slightest notion of how to go about catching a spy. Unlike her sister-in-law Amy, Henrietta had spent her youth playing with dolls and reading novels, not tracking the fastest way to Calais in the event that one was to be chased from Paris by French police, or learning how to transform oneself into a gnarled old onion seller.

Now, there was an idea! If anyone would know how to go about tracking down France’s deadliest spy with the maximum flair, it would be Amy. Among other things, on their return from France, Amy and Richard had converted Richard’s Sussex estate into a clandestine academy for secret agents, laughingly referred to within the family as the Greenhouse.

There was nothing like getting advice from the experts, thought Henrietta airily as she flung letter and codebook aside and skipped across the room to her escritoire. Turning the key, she lowered the lid with an exuberant thump and yanked over a little yellow chair.

‘Dearest Amy,’ she began, dabbing her quill enthusiastically in the inkpot. ‘You will be delighted to know that I have determined to follow your fine example…’

After all, Henrietta thought, writing busily, she was really doing the War Office a favour, providing them with an extra agent at no additional cost. Goodness only knew whom the War Office might assign to the task if left to themselves.

Chapter Three

Morning Call: a consultation with an agent of the War Office

– from the Personal Codebook of the Pink Carnation

‘You sent for me?’ The Honourable Miles Dorrington, heir to the Viscount of Loring and general rake about town, poked his blond head around the door of William Wickham’s office.

‘Ah, Dorrington.’ Wickham didn’t look up from the pile of papers he had been perusing as he gestured to a seat on the opposite side of his cluttered desk. ‘Just the man I wanted to see.’

Miles refrained from pointing out that sending a note bearing the words ‘Come at once’ did tend to radically increase the odds of seeing someone. One simply didn’t make that sort of comment to England’s chief spymaster.

Miles manoeuvred his tall frame into the small chair Wickham had indicated, propping his discarded gloves and hat against one knee, and stretching out his long legs as far as the tiny chair would allow. He waited until Wickham had finished, sanded, and folded the message he was writing, before uttering a breezy ‘Good morning, sir.’

Wickham nodded in reply. ‘One moment, Dorrington.’ Inserting the end of a wafer of sealing wax into the candle on his desk, he expertly dripped several drops of red wax onto the folded paper, stamping it efficiently with his personal seal. Moving briskly from desk to door, he handed it to a waiting sentry with a few softly spoken words. All Miles caught was ‘by noon tomorrow.’

Returning to his desk, Wickham eased several pieces of paper out of the organised chaos, tilting them towards himself. Miles resisted the urge to crane his head to read what was on the first page.

‘I hope I haven’t come at a bad time,’ Miles hedged, with an eye on the paper. Unfortunately, the paper was of good quality; despite the candle guttering nearby, there was no way of reading through the page, even if Miles had ever mastered the art of reading words backwards, which he hadn’t.

Wickham cast Miles a mildly sardonic look over the edge of what he was reading. ‘There hasn’t been a good time since the French went mad. And it has been getting steadily worse.’

Miles leant forward like a spaniel scenting a fallen pheasant. ‘Is there more word on Bonaparte’s plans for an invasion?’

Wickham didn’t bother to answer. Instead, he continued perusing the paper he held in his hand. ‘That was good work you did uncovering that ring of spies on Bond Street.’

The unexpected praise took Miles off guard. Usually, his meetings with England’s spymaster ran more to orders than commendations.

‘Thank you, sir. All it took was a careful eye for detail.’

And his valet’s complaints about the poor quality of cravats the new merchants were selling. Downey noticed things like that. His suspicions piqued, Miles had done some ‘shopping’ of his own in the back room of the establishment, uncovering a half dozen carrier pigeons and a pile of minuscule reports.

Wickham thumbed abstractedly through the sheaf of papers. ‘And the War Office is not unaware of your role in the Pink Carnation’s late successes in France.’

‘It was a very minor role,’ Miles said modestly. ‘All I did was bash in the heads of a few French soldiers and—’

‘Nonetheless,’ Wickham cut him off, ‘the War Office has taken note. Which is why we have summoned you here today.’

Despite himself, Miles sat up straighter in his chair, hands tightening around his discarded gloves. This was it. The summons. The summons he had been waiting for for years.

Seven years, to be precise.

France had been at war with England for eleven years; Miles had been employed by the War Office for seven. Yet, for all his long tenure at the War Office, for all the time he spent going to and from the offices on Crown Street, delivering reports and receiving assignments, Miles could count the number of active missions he’d been assigned on the fingers of one hand.

That was one normal-sized hand with five measly fingers.

Mostly, the War Office had looked to Miles to provide them a link with the Purple Gentian. Given that Miles was Richard’s oldest and closest friend, and spent even more time at Uppington House than he did at his club (and he spent far more time at his club than he did at his own uninspiring bachelor lodgings), this was not a surprising choice on the part of the War Office.

During Richard’s tenure as the Purple Gentian, the two of them had worked out a system. Richard gleaned intelligence in France, and relayed it back to the War Office via meetings with Miles. Miles, for his part, would then pass along any messages the War Office might have back to Richard. Along the way, Miles picked up the odd assignment or two, but his primary role was as liaison with the Purple Gentian. Nothing more, nothing less. Miles knew it was an important role. He knew that without his participation, it was quite likely that the French would have suspected Richard’s dual identity years before Amy’s involvement had precipitated the matter. But, at the same time, he couldn’t help but feel that his talents might be put to better – and more exciting – use. He and Richard had, after all, apprenticed for this sort of thing together. They had snuck down the same back stairs at Eton, read the same dashing tales of heroism and valour, shared the same archery butts, and made daring escapes from the same overcrowded society ballrooms, pursued by the same matchmaking mamas.

When Richard had discovered that his next-door neighbour, Sir Percy Blakeney, was running the most daring intelligence effort since Odysseus asked Agamemnon whether he thought the Trojans might like a large wooden horse, Richard and Miles had gone together to beg Percy for admittance into his league. After considerable pleading, Percy had relented in Richard’s case, but he still refused Miles. He tried to fob Miles off with ‘You’ll be of more use to me at home.’ Miles pointed out that the French were, by definition, in France, and if he wanted to rescue French aristocrats from the guillotine, there was really only one place to do it. Percy, with the air of a man facing a tooth extraction, had poured two tumblers of port, passed the larger of the two to Miles, and said, ‘Sink me if I wouldn’t like to have you along, lad, but you’re just too damned conspicuous.’

And there was the problem. Miles stood six feet, three inches in his bare feet. Between afternoons boxing at Gentleman Jackson’s and fencing at Angelo’s, he had acquired the kind of musculature usually seen in Renaissance statuary. As one countess had squealed upon Miles’s first appearance on the London scene, ‘Ooooh! Put him in a lion skin and he’ll look just like Hercules!’ Miles had declined the lion skin and other more intimate offers from the lady, but there was no escaping it. He had the sort of physique designed to send impressionable women into palpitations and Michelangelo running for his chisel. Miles would have traded it all in a minute to be small, skinny, and inconspicuous.

‘What if I hunch over a lot?’ he suggested to Percy.

Percy had just sighed and poured him an extra portion of port. The next day, Miles had offered his services to the War Office, in whatever capacity they could find. Until now, that capacity had usually involved a desk and a quill rather than black cloaks and dashing midnight escapades.

‘How may I be of service?’ Miles asked, trying to sound as though he were called in for important assignments at least once a week.

‘We have a problem,’ began Wickham.

A problem sounded promising, ruminated Miles. Just so long as it wasn’t a problem to do with the supply of boots for the army, or carbines for their rifles, or something like that. Miles had fallen for that once before, and had spent long weeks adding even longer sums. At a desk. With a quill.

‘A footman was found murdered this morning in Mayfair.’

Miles rested one booted leg against the opposite knee, trying not to look disappointed. He had been hoping for something more along the lines of ‘Bonaparte is poised to invade England, and we need you to stop him!’ Ah, well, a man could dream.

‘Surely that’s a matter for the Bow Street Runners?’

Wickham fished a worn scrap of paper from the debris on his desk. ‘Do you recognise this?’

Miles peered down at the fragment. On closer inspection, it wasn’t even anything so grand as a fragment; it was more of a fleck, a tiny triangle of paper with a jagged end on one side, where it had been torn from something larger.

‘No,’ he said.

‘Look again,’ said Wickham. ‘We found it snagged on a pin on the inside of the murdered man’s coat.’

It was no wonder the murderer had overlooked the lost portion; it was scarcely a centimetre long, and no writing remained. At least, no writing that was discernible as such. Along the tear, a thick black stroke swept down and then off to the side. It might be the lower half of an uppercase script I, or a particularly elaborate T.

Miles was just about to admit ignorance for a second time – in the hopes that Wickham wouldn’t ask him a third – when recognition struck. Not the lower half of an I, but the stem of a flower. A very particular, stylised flower. A flower Miles hadn’t seen in a very long time, and had hoped never to see again.

‘The Black Tulip.’ The name tasted like hemlock on Miles’s tongue. He repeated it, testing it for weight after years of disuse. ‘It can’t be the Black Tulip. I don’t believe it. It’s been too long.’

‘The Black Tulip,’ countered Wickham, ‘is always most deadly after a silence.’

Miles couldn’t argue with that. The English in France had been most on edge not when the Black Tulip acted, but when he didn’t. Like the grey calm before thunder, the Black Tulip’s silence generally presaged some new and awful ill. Austrian operatives had been found dead, minor members of the royal family captured, English spies eliminated, all without fuss or fanfare. For the past two years, the Black Tulip had maintained a hermetic silence.

Miles grimaced.

‘Precisely,’ said Wickham. He extricated the scrap of paper from Miles’s grasp, returning it to its place on his desk. ‘The murdered man was one of our operatives. We had inserted him into the household of a gentleman known for his itinerant tendencies.’

Miles rocked forward in his chair. ‘Who found him?’

Wickham dismissed the question with a shake of his head. ‘A scullery maid from the kitchen of a neighbouring house; she had no part in it.’

‘Had she witnessed anything out of the ordinary?’

‘Aside from a dead body?’ Wickham smiled grimly. ‘No. Think of it, Dorrington. Ten houses – at one of which, by the way, a card party was in progress – several dozen servants coming and going, and not one of them heard anything out of the ordinary. What does that suggest to you?’

Miles thought hard. ‘There can’t have been a struggle, or someone in one of the neighbouring houses would have noticed. He can’t have called out, or someone would have heard. I’d say our man knew his killer.’ A hideous possibility occurred to Miles. ‘Could our chap have been a double agent? If the French thought he had outlived his usefulness…’

The bags under Wickham’s eyes seemed to grow deeper. ‘That,’ he said wearily, ‘is always a possibility. Anyone can turn traitor given the right circumstances – or the right price. Either way, we find ourselves with our old enemy in the heart of London. We need to know more. Which is where you come in, Dorrington.’

‘At your disposal.’

Ah, the time had come. Now Wickham would ask him to find the footman’s murderer, and he could make suave assurances about delivering the Black Tulip’s head on a platter, and…

‘Do you know Lord Vaughn?’ asked Wickham abruptly.

‘Lord Vaughn.’ Taken off guard, Miles racked his memory. ‘I don’t believe I know the chap.’

‘There’s no reason you should. He only recently returned from the Continent. He is, however, acquainted with your parents.’

Wickham’s gaze rested piercingly on Miles. Miles shrugged, lounging back in his chair. ‘My parents have a wide and varied acquaintance.’

‘Have you spoken to your parents recently?’

‘No,’ Miles replied shortly. Well, he hadn’t. That was all there was to it.

‘Do you have any knowledge as to their whereabouts at present?’

Miles was quite sure that Wickham’s spies had more up-to-date information on his parents’ whereabouts than he did.

‘The last time I heard from them, they were in Austria. As that was over a year ago, they may have moved on since. I can’t tell you more than that.’

When was the last time he had seen his parents? Four years ago? Five?

Miles’s father had gout. Not a slight dash of gout, the sort that attends overindulgence in roast lamb at Christmas dinner, not periodic gout, but perpetual, all-consuming gout, the sort of gout that required special cushions and exotic diets and frequent changing of doctors. The viscount had his gout, and the viscountess had a taste for Italian operas, or, more properly, Italian opera singers. Both those interests were better served in Europe. For as long as Miles could remember, the Viscount and Viscountess of Loring had roved about Europe from spa to spa, taking enough waters to float a small armada, and playing no small part in supporting the Italian musical establishment.

The thought of either of his parents having anything to do with the Black Tulip, murdered agents, or anything requiring more strenuous activity than a carriage ride to the nearest opera house strained the imagination. Even so, it made Miles distinctly uneasy that they had come to the attention of the War Office.

Miles put both feet firmly on the floor, rested his hands on his knees, and asked bluntly, ‘Did you have a reason for enquiring after my parents, sir, or was this merely a social amenity?’

Wickham looked at Miles with something akin to amusement. ‘There’s no need to be anxious on their account, Dorrington. We need information on Lord Vaughn. Your parents are among his social set. If you have occasion to write to your parents, you may want to ask them – casually – if they have encountered Lord Vaughn in their travels.’

In his relief, Miles refrained from pointing out that his correspondence with his parents, to date, could be folded into a medium-sized snuffbox. ‘I’ll do that.’

‘Casually,’ cautioned Wickham.

‘Casually,’ confirmed Miles. ‘But what has Lord Vaughn to do with the Black Tulip?’

‘Lord Vaughn,’ Wickham said simply, ‘is the employer of our murdered agent.’

‘Ah.’

‘Vaughn,’ continued Wickham, ‘is recently returned to London after an extended stay on the Continent. A stay of ten years, to be precise.’

Miles engaged in a bit of mental math. ‘Just about the time the Black Tulip began operations.’

Wickham didn’t waste time acknowledging the obvious. ‘You move in the same circles. Watch him. I don’t need to tell you how to go about it, Dorrington. I want a full report by this time next week.’

Miles looked squarely at Wickham. ‘You’ll have it.’

‘Good luck, Dorrington.’ Wickham began shuffling papers, a clear sign that the interview had come to a close. Miles levered himself out of the chair, pulling on his gloves as he strode to the door. ‘I expect to see you this time next Monday.’

‘I’ll be here.’ Miles gave his hat an exuberant twirl before clapping it firmly onto his unruly blond hair. Pausing in the doorway, he grinned at his superior. ‘With flowers.’

Chapter Four

‘The Black Tulip?’

Colin grinned. ‘Somewhat unoriginal, I admit. But what can you expect from a crazed French spy?’

‘Isn’t there a Dumas novel by that name?’

Colin considered. ‘I don’t believe they’re related. Besides, Dumas came later.’

‘I wasn’t suggesting that Dumas was the Black Tulip,’ I protested.

‘Dumas’s father was a Napoleonic soldier,’ Colin pronounced with an authoritative wag of his finger, but spoilt the effect by adding, ‘Or perhaps it was his grandfather. One of them, at any rate.’

I shook my head regretfully. ‘It’s too good a theory to be true.’

I was sitting in the kitchen of Selwick Hall, at a long, scarred wooden table that looked like it had once been victim to beefy-armed cooks bearing cleavers, while Colin poked a spoon into a gooey mass on the stove that he promised was rapidly cooking its way towards being dinner. Despite the well-worn flagstones covering the floor, the kitchen appliances looked as though they had been modernised at some point in the past two decades. They had begun life as that ugly mustard yellow so incomprehensibly beloved of kitchen designers, but had faded with time and use to a subdued beige.

It wasn’t a designer’s showcase of a kitchen. Aside from one rather dispirited pot of basil perched on the windowsill, there were no hanging plants, no gleaming copper pots, no colour-coordinated jars of inedible pasta, no artistically arranged bunches of herbs poised to whack the unwary visitor on the head. Instead, it had the cosy air of a room that someone actually lived in. The walls had been painted a cheery, very un-mustardy yellow. Blue-and-white mugs hung from a rack above the sink; a well-used electric kettle stood next to a battered brown teapot with a frayed blue cosy; and brightly patterned yellow-and-blue drapes framed the room’s two windows. The refrigerator made that comfortable humming noise known to refrigerators around the world, as soothing as a cat’s purr.

A fall of ivy half-blocked the window over the sink, draping artistically down one side. Through the other, the dim twilight tended to obscure more than it revealed, that misty time of day when one can imagine ghost ships sailing endlessly through the Bermuda Triangle or phantom soldiers refighting long-ago battles on deserted heaths.

Clearly, I had been spending too much time cooped up in the library. Phantom soldiers, indeed!