Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

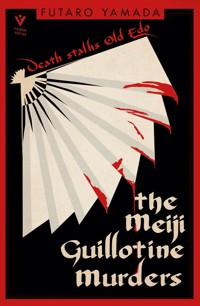

Tokyo, 1869. It is the dawn of the Meiji era in Japan, but the scars of the bloody recent civil war are yet to heal. The new regime struggles to keep the peace as old scores are settled and dangerous new ideas flood into the country from the West.A new police force promises to bring order to this land of feuding samurai warlords, and chief inspectors Kazuki and Kawaji are two of its brightest stars. Together they investigate a spree of baffling murders across the capital, moving from dingy drinking dens to high-class hotels and the heart of the Imperial Palace. Can they solve these seemingly impossible crimes and save the country from slipping into chaos once more?Taking us deep into the heart of 19th century Tokyo, The Meiji Guillotine Murders is a fiendish murder mystery from one of Japan's greatest crime writers.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 494

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

A Brief Historical Note

When Commodore Matthew Perry’s notorious ‘Black Ships’ arrived at Uraga in 1853, Japan had been governed by the military dictatorship known as the Tokugawa shogunate for two and a half centuries. Throughout this time, the shogunate had enforced a strict policy of isolationism and seclusion, yet Perry’s ships had come to end all that, forcing upon Japan a treaty that would see, among other things, the country opened up to international trade and diplomacy.

Anxiety over the influence that contact with the outside world would bring led the puppet Emperor Kōmei to issue an edict in 1863, breaking with centuries of tradition and calling for the foreign ‘barbarians’ to be expelled from Japan. When the shogunate failed to enforce the edict, however, a schism ensued, and samurai loyal to the emperor coalesced around the rallying cry sonnō jōi: Revere the Emperor, Expel the Barbarians! Following a spate of high-profile political assassinations, widespread unrest and rebellion eventually turned into a full-scale civil war, known as the Boshin War, with the southern provinces of Satsuma and Chōshū forming a military alliance against the shogunate.

While the victory of this alliance did bring about the restoration of imperial rule, the new Emperor Meiji’s youth meant that power rested in the hands of an oligarchy of former samurai from Satsuma and Chōshū, the most influential of whom were Toshimichi Ōkubo, Takamori Saigō and Takayoshi Kido. This new government soon realized, however, that without reform and modernization, Japan would lag behind the Western world and leave itself open to the threat of colonization. Consequently, it not only continued to trade with the West, but also pursued a policy of rapid Westernization—all of which consolidated a sense of betrayal among many of those who had fought for the emperor.

The ensuing years of social change and acute political turmoil are where this story begins. Readers should be aware that the old capital Edo has just been renamed Tokyo, and that dates are given according to the traditional Japanese calendar—that is, with years reckoned according to periods of imperial rule, and months according to the lunar calendar.

THE CHIEF INSPECTORATE OF THE IMPERIAL PROSECUTING OFFICE

1

As great wars and great revolutions reach their end, most nations seem to enter a fallow period lasting several years.

After such tremendous bloodshed, troubles arising from the victors’ arrogance and lust for retribution, as well as from the losers’ sense of disgrace and resentment, will inevitably flare up and prevail over the hour of peace, yet still the vantage of history will somehow lend the impression that these years were in some way empty. The period after the Second World War is a case in point. And the early years of the Meiji era, too, were much the same.

Never had there been so nationwide a sense of collapse as there was when the Boshin War ended, but then nor had there ever been so profound a sense of heartfelt relief at the dawning of peace. It seems, however, that both sides then fell hopelessly into a state of total confusion, with neither one having any idea where to begin or what to do. For the people living then, those years must have seemed anything but fallow; rather, it must have been a time of great turmoil, of life-or-death struggle. It was a time when new government offices sprouted up like bamboo shoots, when new administrative orders came down from on high like rain, and when new customs and ideas came flooding in like a deluge from a harbour. By the same stroke, however, it was also a time when even stranger offices, laws and notions from the old days were revived like the souls of the departed and combined, as though mixing together the seven colours of the rainbow—who could say then whether for better or worse—with the end result a chaos of ash-grey.

This period of chaos-cum-fallowness seems to have lasted until around 1873, the sixth year of Emperor Meiji’s reign, when the famed Iwakura Mission returned from its embassy travelling in the United States and Europe. From the observations made by this group of high-ranking officials, a blueprint was drawn up, one that sought to refashion Japan in Europe’s likeness, one that would set her on course not only to catch up with, but to overtake the West, and one whose consequences would be felt not only in the Meiji era, but right up to the Second World War and even afterwards.

In his autobiography, the writer Yukichi Fukuzawa observes: ‘The years on either side of the Meiji Restoration, from the second or third year of Bunkyū to the sixth or seventh of Meiji, were the most dangerous. During those twelve or thirteen years, I never ventured out of my house in Tokyo at night.’ Lines such as these make clear the extent to which these supposedly fallow years were fallow also in terms of public order.

This does not mean, however, that the capital was entirely without law enforcement. In the first year of Meiji, 1868, while the loyalist army was stationed in old Edo, the magistrate’s office was reformed as a municipal court. Later, the soldiers loyal to the various ruling clans took control of the city and, in the sixth lunar month of the second year, a hired militia was appointed to the role. Finally, by the eleventh lunar month of the fourth year, the rasotsu system was implemented, although the term itself was already in use beforehand. But whatever the name or the system, law enforcement itself was, at any rate, to borrow a phrase from the Kojiki, a tale of ‘when the world was yet young and like unto floating oil, drifting medusa-like’.

And so, let us now go back to the autumn of the second year of Meiji.

There were once five rasotsu in Tokyo…

2

The district of Akashi-chō, where the Tsukiji Foreign Settlement was located, is bound to the east by the mouth of the Great Sumida River but surrounded on all other sides by canals and waterways. Each of the many bridges there had a guardhouse, and that was where the rasotsu were stationed.

The settlement had been built for the protection of foreign residents, but though guardhouses had been erected, very few foreigners actually availed themselves of them. And so, while in the early days there had been multiple guards stationed in them, now they had just one lone sentry.

At his post one afternoon, Sergeant Jirōmasa Saruki was having some sport with a drunken man.

Actually, it would be more apt to say that the man was sobering up. The foreign settlement, you see, also contained a pleasure quarter: Shin-Shimabara. It was open to foreigners, with the women having been brought in from the more famous Yoshiwara, but, as with the guardhouses, it was rarely frequented by its intended patrons, and on the whole its clientele was Japanese. The man seemed to be a regular of these establishments. For some reason, though, he had got so drunk that morning that he had been staggering about like a somnambulist. Saruki had brought him in ‘for his own good’.

It had been about eleven o’clock in the morning when the man collapsed onto the floor of the guardhouse and fell asleep, snoring dreadfully. He had awoken only moments ago, a little before four o’clock that afternoon.

As he looked around in confusion, the drunk, who wore the clothes of a merchant, noticed the rasotsu’s monkey-like face with its upward-pointing moustache glaring at him from the desk, and sat up in astonishment.

‘You’re in the Karuko Bridge guardhouse, in the foreign settlement. You were so drunk that, as you were coming over the bridge, you looked as though you might fall over the railing at any moment, so I brought you here.’

‘Oh… Thank you…’

‘What were you doing drinking at such an ungodly hour?’

‘Well, you see, I quarrelled with one of the working girls and she ran off in the middle of the night. I was so angry that I had one of the young serving lads fetch me some sake, and before I knew it, it was dawn. That’s about as much as I can remember. Was I really that drunk?’

As he bowed and scraped in embarrassment, the man searched furiously inside the breast of his kimono and in the pockets of his sleeves.

‘Look at me!’ the sergeant barked. ‘Who are you? I need your name, age, address, occupation…’

Wearing another look of astonishment, the man lifted his head.

‘My name is Shimbei. Shimbei Takaya,’ he replied, still groping all over his body. ‘I’m thirty-eight, and I run a lamp shop in Kotobuki-chō, in Asakusa.’

‘Looking for something?’

‘It’s just, my money… No matter how much I drank, there should still be a fair amount left.’

‘It’s here.’ Sergeant Saruki tossed the man’s coin purse onto the desk. ‘I’ve been keeping it safe for you.’

‘Ah, that’s awfully kind of you. Thank you, Sergeant.’

With a show of gratitude, the man picked up his coin purse and set about inspecting its contents.

‘One ryō, two ryō… two bu… and one shu,’ he said, counting it all out. Then, having satisfied himself, he nodded and prostrated himself in gratitude on the floor. ‘All present and correct. You’ve been a real help to me, Sergeant. Well, if that’s all…’ he said, getting to his feet.

‘Just one minute,’ said Saruki, stopping him in his tracks. ‘If you’d collapsed like that in the middle of the street, any passer-by could have come along and robbed you, taking the whole lot. Thanks to me, you were spared from that injustice. Don’t you think you ought to show a bit more gratitude?’

‘Oh, but I already… What I mean to say is… Thank you. I really am most awfully grateful to you.’

‘Come on, do you really think this is the sort of thing that can be repaid with words alone? Hmm?’

The lamp-seller blinked as he beheld the sergeant’s face, his jaw thrust out over the desk. Suddenly, the man’s face creased into an awkward smile.

‘I hadn’t realized… Of course, I must thank you properly,’ he said, fumbling around in his coin purse. He extracted a two-bu gold coin and offered it to the rasotsu.

‘Kindly accept this token of my gratitude, sir. Now, if that’s all?…’

‘It is not!’ Saruki snarled, thrusting his chin out further still. ‘Think about it. Why, if I hadn’t rescued you, you’d have fallen off the bridge before you knew it. Is saving your life really worth only two bu?’

The lamp-seller panicked.

‘Ah, well, when you put it like that… You can’t really put a price on—’

‘Don’t you think that three, even four coin purses like this would still be nothing compared to a man’s life? Hmm?’

The lamp-seller took a deep breath and looked at the man across from him. But the rasotsu’s face was deadly serious, and suddenly a look of irritation flashed in his eyes. A few seconds later, the lamp-seller bowed again, so low this time that his forehead practically hit the floor.

‘I really do apologize. It’s just as you say, sir. Here, please, take the purse and its contents,’ he said, holding it out in desperation.

Saruki snatched it from his hands. Then, as the lamp-seller made his way out of the guardhouse, stumbling as he went, as though his drunkenness had suddenly returned to him, the rasotsu called after him in an ingratiating tone:

‘It’s a relief, in any case, to know that everything was “all present and correct”.’

The sergeant then tipped out the coins and spread them across the desk.

There were gold coins worth two bu and silver coins worth one bu or one shu, all mixed together. Just as he had said: two ryō, two bu and one shu in total.

While there was all manner of chaos in those first years of Meiji, this was never truer than where money was concerned. In the previous year, the new government had immediately set about issuing banknotes, but these were hardly in common use. On the other hand, the coins from the old days of the shogunate were still in circulation, but both the values and the denominations of those coins were really quite negligible, and, to make matters worse, there were a prodigious number of counterfeits mixed in. Looking back, it seems miraculous that society didn’t just fall apart in those days.

One by one, Saruki picked up the coins and dropped them onto the desk, checking whether or not they were counterfeit.

Despite the chaos, this was over two and half ryō in an era when you could buy a whole sack of rice for five ryō and still have change left over. He was thankful not to find a single worthless government bill. And better yet, each of the coins appeared to be the genuine article. As he listened carefully to the sound of each coin landing on the desk, Sergeant Jirōmasa Saruki was in a world of his own, his face ecstatic. But suddenly he noticed a figure standing in front of the guardhouse, and so he began to gather up the scattered coins in a fluster.

3

‘Case closed!’

The man who had just stepped into the guardhouse was not stationed in the foreign concession, but he was a rasotsu. His name was Heikurō Imokawa, and he was an old friend of Saruki’s.

Imokawa broke into a broad grin, revealing his rodent-like features.

‘I just ran into a man staggering about outside… So, how much did you manage to get out of him?’ he asked, rubbing his palms and his stubby fingers together.

‘Ugh, you’re just like a magpie,’ said Saruki, clicking his tongue and tossing a one-shu silver coin onto the desk.

With tremendous dexterity, surprising in one so fat, Sergeant Imokawa took the coin in hand.

‘Pure coincidence! Anyway, I came to tell you that, since Ichinohata seems to be so mysteriously in clover lately, I’ve been on at him to come to Yoshiwara or Shin-Shimabara one of these nights. Do you want to come along? You look as though you could do with it.’

‘What, is that all?’ Saruki spat out with contempt as he covered the money on the desk with his hand, tipped it back into the coin purse and placed it into his pocket. ‘All right, fine. Shall we go and see Ichinohata, then?’

‘Are you sure you can leave? The duty officer hasn’t come to relieve you yet.’

‘Don’t worry. Half the time, nobody shows up anyway.’

With that, Saruki picked up his sword in its red-lacquered scabbard and, pressing Imokawa ahead of him, left the guardhouse.

Heikurō Imokawa gazed out at the many steamers plying the waterways and floating in the blue mouth of the river. As he looked back towards the foreign settlement, his eyes came to rest on a brick building, and he stared up at the exotic-looking tower atop the roof of the Tsukiji Hotel.

‘Is this how everything’s going to be in Japan now?’ he muttered.

Saruki chuckled, his monkey-like face creasing into a sneer.

‘What’s it to us what happens to the country?’

‘True enough,’ Imokawa replied with a chuckle.

They walked off. Jirōmasa Saruki was of slight build, whereas Heikurō Imokawa was thick-set. The two were still wearing their uniforms.

The jacket looked like a cross between a modern-day suit and a frock coat, but, since it had no buttons, it fastened at the front like a kimono. The trousers—the so-called danbukuro, which looked like swollen elephant’s legs—were completely black, but for the waistband of bleached cotton holding them up. This bizarre ensemble was worn together with a sword in a red-lacquered scabbard, and, crowning the head, an old-fashioned nirayama-style hat. Not one of the items they wore was in decent condition.

While it was still common for policemen to wear straw sandals, Saruki, surprisingly, had on a pair of shoes. They were monstrously large—almost one and a half times too big for him—and he had purloined them from an imported-goods shop in the foreign settlement. To secure them, he tied the laces around his ankles, and would go striding off with a triumphant clatter. If nothing else, they at least spared him the cost of straw sandals.

So, as the reader has seen, Saruki was the sort of sergeant who enjoyed menacing the general public and extorting money out of them, whereas Imokawa had the habit of sponging off of Saruki and others of his disreputable ilk. Whenever his friend came by some easy money, he would always somehow manage to appear out of nowhere. Hence Saruki’s earlier complaint that he was like a magpie. It was never his style to threaten; he would just crease his rodent-like face into a broad grin, clap his hands together and flatter a person so brazenly that nobody could ever be angry with him. What’s more, this man had an uncanny nose and could always sniff out petty crimes that promised to be lucrative. Only, he would never sully his own hands, having developed instead the habit of entrusting the matters to his colleagues and, no matter the money, taking only a small commission from them. And so, it was impossible to escape him.

As the pair walked in the direction of Nihonbashi, three or four strange-looking vehicles crossed their path. I say ‘strange’ because, although these were in fact rickshaws, they had only begun to spring up that summer, and, still curious to the eye, they looked like an odd combination of the old two-wheeled cart with a sort of palanquin set on top. Passing by with cries of joy and laughter, a group of what appeared to be students was speeding towards the Nishi Hongan-ji temple.

‘What’s all this?’ Imokawa asked.

‘It’s all those spongers who live with that government bigwig Shigenobu Ōkuma in his mansion by Nishi Hongan-ji,’ said Saruki, frowning. ‘In the days before the Restoration, it belonged to one of the shogun’s bannermen, a man by the name of Togawa. But these days, some upstarts in the government are loafing around the place, talking up some rubbish about how they’re going to change the world, all argued over cups of sake. They say they’re causing such a racket that the neighbours can’t sleep, even though the grounds of the mansion are five thousand tsubo.’

On the streets running along the canals, there were many mansions lying empty that had once belonged to various daimyo, or high-ranking samurai. After their inhabitants left for their hometowns or else fled to who knows where, any residence of note had been seized and turned over to the new government or else sold to government officials. Under the shogun, however, some sixty per cent of the land in Edo had belonged to the old samurai clans, so there were mansions that had been left untouched all over the place.

‘Hey, isn’t that…’ said Saruki.

In front of the entrance to one mansion in Hatchōbori, they spotted a large man shouting, and the two of them stopped in their tracks. The mansion had previously belonged to a bannerman, but the gate was in ruins and you could see from the street that the garden inside was overgrown with weeds.

‘I’m a representative of the Grand Council of State and I have come about the garden! This place has failed its inspection! If you don’t open up, this site will be seized immediately!’

Though he was facing away from them, the man cut an imposing figure, and he was brandishing a wooden notice-board in his hand.

‘He’s up to something,’ replied Imokawa.

‘It’s Tamonta Onimaru,’ Saruki muttered.

Unsteady on his feet, an old man came hurrying out of the dilapidated entrance and started bowing and scraping before the imposing rasotsu. Sergeant Onimaru was tapping on the noticeboard as he carried on reprimanding him.

That summer, the new government had issued a proclamation ordering all owners of mansions with gardens to plant mulberry trees or tea plants immediately. (In those days, raw silk and tea were Japan’s leading exports, so this was but one example of the heroic efforts the new government was making in the belief that it had to act, even if its ideas were in short supply.) What’s more, it had also threatened to seize any vacant land and gardens that were not being put to good use and had been allowed to go to seed.

The noticeboard bore the words ‘Crown Property’. However, Saruki and Imokawa were well aware that Sergeant Onimaru had written those words himself.

Before long, having extracted from the old man a certain sum to ‘overlook’ the incident, Sergeant Onimaru came out of the front entrance, noticeboard in hand, and scowled when he spotted the two other gentlemen. His bearded face was fearsome to behold.

They both held out their hands. Eventually, still scowling, Sergeant Onimaru opened the envelope and handed them one ryō each.

‘How many places have you been to?’ asked Imokawa.

‘And just where are the pair of you going?’ he fired back without answering the question.

‘Where indeed!’

‘We’re on our way to Denma-chō, to see Sohachi Ichinohata,’ Saruki replied.

When Saruki informed Onimaru that Ichinohata had, it seemed, lately found himself a nice little source of income, he said:

‘Why don’t I join you? I haven’t seen Sohachi’s face in a long while.’

With a nod, he snapped the homemade noticeboard in half with his foot and tossed it into the gutter at the bottom of the mansion wall. And so, the three of them set off together.

As they were about to cross the Edobashi Bridge, Imokawa suddenly looked around.

‘Hmm, I wonder…’ he said, twisting his neck.

‘What is it?’ Onimaru asked.

‘You see that samurai walking over there, the one in the fuka-amigasa hat? Look! He’s stopped dead in his tracks.’

A few paces behind them, just as he said, there was a man wearing a black-crested haori jacket and a pair of hakama, with a large straw hat covering his face, trying to light his pipe with a match.

‘He’s not been following us, has he?’

‘Why would you think that?’

‘He’s been following me ever since the end of summer. I don’t know about before that, but I’ve a feeling that I’ve seen him four, maybe five times since then. I don’t involve myself in nefarious dealings like you two, though, so I can’t think why anyone would want to follow me. There’s nobody with a grudge against me,’ said Imokawa.

‘What on earth are you on about?’

‘Do either of you recognize him?’

‘I don’t, no. That being said, it’s an outrage that anybody should be following an officer of the law! Right, I’ll arrest him and find out,’ said Onimaru, ready to turn on his heels, when Imokawa quickly stopped him.

‘Wait! Wait! He looks strong. I have a feeling that you’re about to kick a hornet’s nest. Besides, I could be wrong about this.’

‘He’s gone!’

After wasting three or four matches in the wind, the man in the straw hat, trailing behind him at last a cloud of blue smoke, had leisurely strolled off, disappearing into an alleyway. He did not seem to be aware of them, so unhurried were his steps.

The three men proceeded to cross the Edobashi Bridge.

The area was full of merchants’ homes and shops, so the crowds of people were no different from what they had been in the years before the Restoration. In fact, there were no fallow days for those people who had to work in order to survive.

There was one sight that did differ from before, however. By the sides of the main thoroughfare, there were people spreading out rugs and woven mats, laying out furniture, swords, dolls, clothes, all manner of things. Mostly, their heads were covered with braided straw hats or the headscarves known as okoso-zukin, and they didn’t call out to passers-by but instead just sat motionlessly, their heads bowed, or else with both hands pressed to the ground in supplication. Even though the bright autumn sun was streaming down, they looked like a host of shadows. Having lost their stipends in the collapse of the previous government, these samurai families had no idea how to survive in the new world in which they found themselves.

‘Ugh… here we go!’ said Imokawa in a strange voice.

‘Is that Heisuke Yokomakura?’ said Saruki, glancing over at the street corner.

The front of the little place was only ten feet wide, and on the half-open sliding door was written: Greater Denma-chō Police Station. (In days past, it would have been called a lock-up.) Behind it, they could just about see the head of a lone sergeant. It was none other than the long face of their friend, Heisuke Yokomakura, but in front of him, with his back to them, there was a man wearing a samurai’s topknot, his head bowed, and beside him what appeared to be girl of sixteen or seventeen—perhaps his daughter, who was cupping her face in both hands and appeared to be crying.

When Sergeant Yokomakura noticed the three of them approaching, he said in a loud voice:

‘Very well, I’ll overlook it this time. Now be off with you!’

When the man turned towards them, the three spotted that he was holding a half-folded fan. They surmised that he must have just given some money to Yokomakura, observing the old custom of offering it on the object. The greying, refined but somewhat frail-looking man and the girl who appeared to be his daughter went tottering out of the police station.

‘What was all that about?’ enquired Sergeant Saruki.

‘Oh,’ said Yokomakura, rubbing his long face in irritation, as though regretting having just raised his voice. ‘It’s a father and daughter who run a shop over there on the main thoroughfare. I just happened to be passing by and heard her disparaging the new government, so I dragged her off. Since her father came to make amends, though, I let her off the hook.’

‘How much did it cost him?’ asked Imokawa.

‘Two bu,’ said Yokomakura, extracting the coins from his pocket and showing them. ‘Apparently, that was all he had. It hardly seems worth the trouble.’

‘But you do this several times a day, surely?’

‘That was my first of the day! Anyway, who would want to be a rasotsu if it weren’t for little bonuses like that?!’ said Yokomakura, smirking unashamedly.

‘Oh, I would! I’m a servant of the people.’

By nature, Imokawa was, of course, a tremendously lazy man.

Feeling little inclined to demand a cut of only two bu, the three of them, each wearing a wry smile, turned to leave the police station, but Yokomakura called after them, stopping them in their tracks. When he asked after Sohachi Ichinohata, it was decided that he, too, should accompany them. Although this would leave nobody manning the police station, he did not seem to mind in the slightest. And so it was that the group of three became a group of four.

Together, they set out for Kodenma-chō, joking and talking loudly, oblivious to the world around them.

4

At Kodenma-chō there was a single block, right in the middle of the neighbourhood. It was enclosed by a long, blackened mud-brick wall some eight feet high and topped with bamboo spikes. Nailed to the wall beside the entrance was a still-new sign bearing the words ‘Tokyo Prison’. Which is to say, this was the notorious Kodenma-chōjail.

‘Hello!’ said Heikurō Imokawa, addressing the two sentries stationed at the entrance. ‘I don’t suppose Sergeant Ichinohata’s around, is he?’

Though the world might have changed drastically, the new government seemed, for the time being, loath to touch the prison’s facilities or its set-up, and the old jailers had been allowed to remain in their posts. Naturally, however, quite a few of them had panicked and run off, and so the situation was that a number of rasotsu had been hired to fill their jobs.

The sentries were also friends of theirs.

‘He is!’

‘Come in!’

With these words from the sentries, the group piled in.

The prison was not a nice place to visit. Just setting foot inside was enough to send shivers down your spine. Sohachi Ichinohata, who worked there, had once offered to give them a tour, but all of them had politely declined, and usually, after a brief chat in a place called ‘jailers’ row’, which was used these days for meetings between visitors and prison officials, they would beat a hasty retreat.

It was this room that they were now heading for.

As they got closer, they could hear a loud voice coming from further inside the building.

‘Give it back! Give me back the money!’

With suspicion written across their faces, the four entered.

In a corner, Ichinohata was standing there crestfallen, his head slumped on his chest. In front of him, a man was reprimanding him, his arm outstretched and almost prodding Ichinohata on the nose.

‘To say nothing of the fact that you’re a just a guard here—’

He turned to look at the four rasotsu who had just entered, but showed no sign of fear.

‘In any case, how is it that an official of His Imperial Majesty’s government could defraud the people?!’

The four of them all turned to one another with looks of embarrassment. Just who could this man be? He must be an outsider, of course, but he was an imposing, fine figure of a man, somewhere in his mid-thirties. He wore a commoner’s topknot and had on a striped kimono that he had tucked up into his waistband, revealing a pair of purple undertrousers. He had a large mouth and a strong jaw, as well as a very lean, sinewy physique, but he didn’t look at all like a samurai. For one thing, he didn’t even carry a sword. And yet, despite this, Ichinohata, who was by nature a timid sort, though still a rasotsu, was visibly trembling in the corner.

It was Onimaru who spoke first.

‘And just who the hell are you to be raising your voice in a place like this?’

‘I, sir? My name is Yukichi Fukuzawa.’

The four of them turned pale. This was no ordinary commoner. Even they knew that this was the name of the renowned Western scholar, who had opened a great place of learning called the Keiōin Shiba Shinsenza.

‘And ju-just what do you mean by “Give me back the money”?’

‘Well, I have some business, you see, with a certain prisoner here. Ever since the summer, I’ve been coming to this jail, bringing him books, clothes, money and what have you. Or at least, that was my intention. I simply assumed that the prisoner was here. When I first came to make a few enquiries, it was this man who told me that he was, and ever since, he’s acted as the intermediary for these provisions,’ said Fukuzawa, his face still puce with rage. ‘But, as it so happens, it was all a sham. Yesterday, I learnt that the man in question is not being held at Kodenma-chō at all. This man has cheated me. How dare he tell such a barefaced lie?! So, I’ve come for an explanation, and to demand the return of all the goods and money I’ve handed over. Are my anger and my demand unjustified?’

He was no longer shouting, but his voice, let alone the meaning of his words, had a force that is difficult to convey.

It was little wonder that Ichinohata was so afraid.

‘They are unjustified!’ Saruki piped up in a high-pitched voice.

‘In what way are they unjustified?’

‘It is, by and large, considered improper to bring inmates goods and money. It’s only natural that they should be confiscated!’

‘If it’s improper, then why were they not returned to me in the first place? Ah-ha! Got you there, haven’t I? Well, in that case, I’m not the only one guilty of wrongdoing, am I?’

‘I won’t stand for this!’ said Onimaru, slapping his red scabbard. ‘You need cutting down to size, you do!’

‘Cut me down? Don’t make me laugh.’

Unbeknownst to the rasotsu, in May of the previous year, at Keiō University, when the rumble of cannon at the Battle of Ueno reverberated like distant thunder, this man had simply carried on with his lecture on Francis Wayland’s treatise on economics. Now, as then, he did not so much as flinch, and instead merely spat out:

‘I was relieved when the overbearing and corrupt officials of the shogunate disappeared, but it appears that, no matter how much the world may change, officials will still be officials. But then, I don’t quite know whether these newfangled rasotsu even count as officials. Apropos of which, let me tell you something. The rasotsu may be policemen in name, but if you ask me, they’re nothing more than roving gangsters. I really shouldn’t say this, but just the other day I went to brief Lord Iwakura on the West’s system of law enforcement, but I didn’t manage to convince him. If a rasotsu were to cut me down with his idiot-meter, then we might see reform a damn sight sooner.’

‘What’s that? Lord Iwakura?’

‘Idiot-meter?’

The rasotsu were dumbfounded.

‘He means your sword! He thinks its length is a measure of your idiocy…’

With a hearty laugh, Fukuzawa suddenly turned towards the open door. There, just outside it, with the setting sun behind his back, stood somebody new. There was a note of madness in his voice, and he cut a very odd figure. The rasotsu, with the exception of Ichinohata, all stared in astonishment.

Not one of them, Fukuzawa included, could put a name to the attire worn by the man, but he had on a pale-blue suikan robe, a pair of hakama with legs that were tied at the ankles and traditional kegutsu furred boots.

‘Can we help you?’ came a suspicious voice from the crowd of rasotsu.

‘And who might you be?’ Fukuzawa finally asked.

‘Chief Inspector Keishirō Kazuki of the Imperial Prosecuting Office, at your service.’

Looking the man over again as he entered, they now saw that he had jet-black hair, worn knotted at the back, and he even had eyebrows drawn on his forehead, as noblemen did in bygone times. Hanging at his waist was a sword that looked like an old-fashioned samurai’s tachi rather than a katana, and in his hand he carried a folded fan made of cypress-wood. Though still a young man in his mid-twenties, this most elegant and handsome figure looked like a courtier who had stepped out of the Heian period.

‘The Imperial Prosecuting Office? I see,’ said Fukuzawa, flabbergasted, mumbling as he thought for a moment. ‘The name of the body is familiar to me. Although I’m astonished that our new government has seen fit to bring out of retirement such an ancient and venerable institution from the annals of our country’s history… even if I do agree with the spirit of it. Simply put, it’s an office to catch malfeasance carried out by government officials, isn’t that it? Well, if so, then I have something important to tell you. I am Yukichi Fukuzawa, rector of Keiō University.’

He introduced himself and once again launched into his tale.

‘There’s a soldier of the old shogunate by the name of Takeaki Enomoto, who, after surrendering in the Battle of Hakodate in the fifth month of this year, was sent to Tokyo. Now, I’m a native of Nakatsu, in Kyushu, and have no connection whatsoever to this Enomoto, but in the summer, quite by chance, I heard that his family, having no inkling what happened to him afterwards, was extremely worried about him. As I say, I myself don’t even have a passing acquaintance with Enomoto, but I was impressed by the fact that he had fought for the shogun right to the bitter end. They lost, I believe, only because they lacked numbers. So, I decided to go out of my way to help. Well, I said to myself, since the man would be deemed a criminal, why not go to the jail in Kodenma-chō and find out? So, when I came here, whom did I happen to meet but that scrawny weed over there. He was the one who had the audacity to tell me that Enomoto was here and that he was looking after him, so, ever since, I’ve been duly coming to drop off books and money and so forth for him. But would you believe, Enomoto has never in fact been here! Yesterday I learnt that he’s being held in the military prison in Tatsu-no-kuchi. That’s why I’m so irate and have come to protest. I don’t regret the money or the goods in the slightest; however, I cannot forgive such a wicked and humiliating lie—rasotsu or not. In fact, it’s precisely because he’s a rasotsu that this cannot be overlooked. Tell me, kind sir, is my objection unreasonable?’

‘It’s perfectly reasonable,’ the young chief inspector replied.

His voice sounded clear, sweet even. He then turned his narrowed eyes towards Ichinohata.

‘Return it.’

‘But… but I can’t,’ said Ichinohata, flustered.

‘You mean to say it’s all been disposed of?’ asked Kazuki. A wry smile creased one of his cheeks. ‘At any rate, this matter will be duly investigated, and it is the government’s responsibility to compensate you for any goods or money that have been misappropriated. Sergeant, if you commit a crime like this ever again, you can be sure that you’ll be punished.’ Kazuki looked not just at Ichinohata, but at all four of the others. ‘Is that understood? You will be punished by the authority of the Imperial Prosecuting Office,’ he repeated. ‘Dismissed.’

The five rasotsu left the meeting room in a daze—in fact, each of them looked as though he had had a narrow escape.

‘Please forgive me,’ said Kazuki, bowing to the rector, who wore a look of considerable dissatisfaction. ‘It’s still early days for the new government, and there are all kinds of disreputable sorts swarming around. It’s hard to catch all of them. The Imperial Prosecuting Office has begun conducting citywide patrols only recently.’

‘Do all the officials of the Imperial Prosecuting Office dress like you?’ Fukuzawa enquired, voicing a question that had been nagging at him.

‘No, I’m afraid it’s just me,’ Kazuki replied with a laugh. ‘If I may, sir, you look as though you have something on your mind.’

‘I’d heard about the establishment of the Imperial Prosecuting Office,’ said Fukuzawa, ‘but, to be honest, I hadn’t much of an idea what it did. Later, I found out that it was a revival of a Heian-period administration set up to investigate and root out official corruption. Rumour has it that there are some very old-fashioned people in its ranks… At any rate, as far as I can see, it isn’t just the likes of the rasotsu that are up to no good. Higher up, there seem to be plenty more disgraceful types trying to line their pockets amid the chaos of the changing times. With all due respect, how much does the Imperial Prosecuting Office know about this, and what measures is it taking to deal with it?’

Looking straight into the eyes of Fukuzawa, who had put the question so bluntly, Kazuki replied:

‘What measures, indeed? As you’re doubtless aware, sir, right now in Tokyo the former residences of various daimyo are lying unoccupied. There are several gangs who, amid all the confusion, would very much like to get their grubby hands on them. We’re conducting secret investigations into such cases. Ah yes, of course! You mentioned your recent visit to Lord Iwakura, to teach him about the Western system of policing. I’m also aware that a mansion in Mita, which belonged to the daimyo of the Shimabara Domain—with a building of some 769 tsubo and grounds of more than 14,000 tsubo—came under discussion. You apparently asked whether it could be sold to you for the low price of one ryō per tsubo, as compensation for your advice.’

Startled, Yukichi Fukuzawa drew a sharp breath, while Keishirō Kazuki merely grinned, revealing a beautiful set of teeth.

‘Sir, how do you think the Imperial Prosecuting Office should go about treating such cases?’

5

That evening, at an izakaya in a backstreet of Nihonbashi Bakuro-chō, four of the rasotsu were drinking.

Having been detained by work at the prison, Ichinohata was running late. By the time he eventually arrived, the others were getting ready to leave.

When asked whether he had been questioned any more about the events earlier, he told them that he hadn’t. Hearing this, Jirōmasa Saruki immediately asked:

‘Hey, Sohachi, so what’s the score with that devil from the Imperial what’s-its-name?’

‘I don’t know,’ replied Ichinohata, cocking his head. ‘He started coming to the prison about ten days ago.’

‘Could he be investigating one of the inmates?’

‘No, but he’s up to something strange.’

‘Strange?’

‘Yes… at the back of the prison, there’s a spot for beheading criminals. He’s had a new hut built there and a large dais erected in the yard. Then, two or three days ago, a wooden box twice as tall as a man was brought in from Yokohama. Well, strictly speaking, it came from France, but it seems to have been ordered by the chief inspector.’

‘What? From France? What could it be, I wonder…’

‘I’ve no idea what’s inside it,’ said Ichinohata, shaking his head feebly. ‘But never mind that. I’m still in trouble after they found out about those packages.’

‘But didn’t you just say that there wasn’t going to be any investigation?’

‘True, but I can’t make any money through that wheeze any more, and I’ve still got plenty of mouths that need feeding and palms that need greasing.’

Leaning over his cup of sake, Ichinohata held his head in his hands.

‘Besides, that chief inspector may look like a soft touch, but still, there’s something uncanny about him.’

‘He did say that you could “be sure of punishment” if you ever did it again…’ said Onimaru, sticking out a generous lower lip from beneath his beard. ‘The little upstart had the cheek to take that high-and-mighty tone… Hey, innkeeper! More sake!’

‘Do you think the Imperial Prosecuting Office will really be keeping an eye on us?’ asked Heikurō Imokawa, beset by anxiety once again.

‘Even if they wanted to, they’d never catch up with us—not if they had thousands of men working for them,’ said Heisuke Yokomakura with a chuckle.

They were truly an incorrigible lot. They wore their authority as a mantle and made it their daily task to cheat people out of their money with all manner of empty threats, extorting and swindling wherever they went. Their hapless victims just assumed that everyone in a position of authority did likewise. That was far from the case, however.

‘That upstart must be from Satsuma or Chōshū, or one of the domains that overthrew the shogunate. Don’t you think? And just what kind of chief inspector goes around in that get-up? Whatever he may say, there’s something crooked about him.’

‘After all, only two or three years ago all these so-called government officials were wanted by the police. Half of them were arsonists, bandits and murderers.’

‘And now they preach to us about “society” and “the nation” and what have you.’

‘Whereas in actual fact, day after day, night after night, they’re buying up every last place in Yanagibashi and having a grand old time of it!’

‘They’re the same people who drummed up unrest and went marching through the streets, chanting, “Expel the barbarians!” They’re the same people who overthrew the shogun and then, when all was said and done, played dumb, as if to say, “Who were all those people chanting? They’ve simply vanished!”’

They began to gabble excitedly over one another, and it was not just the alcohol talking. They were filled with genuine indignation over the state of the country.

‘They aren’t just playing dumb! They’ve been allowed to give full vent to their greed and lust with absolute impunity. Ichinohata, next time you meet that devil, tell him that if he means to go after anyone, it’s the top officials he should be looking at! The government ministers and councillors of state. Why, they aren’t much older than we are! In fact, some of them are even younger!’

‘And they’re all raking it in, while we have to go to these unspeakable lengths just to scrape together enough money to buy some cheap whore from the pleasure quarter.’

‘It’s a world gone mad, damn it… Innkeeper! We’re out of sake! And hey, give us all that octopus you’ve got there!’

The innkeeper wore a pained expression. He had no other customers, for they had all skulked off the moment they saw the rasotsu traipsing in.

The five of them were all former members of a security unit that was set up at the end of the Edo period: the so-called Shinchō-gumi. In the early 1860s, the shogunate had scraped together the masterless samurai known as rōnin to keep order in the city of Edo, but in their final days, far from keeping order, they had turned into a plague, blackmailing and extorting money from the citizens. Thinking back on it now, though, while their conduct used to be more brazen, they had nevertheless had high hopes for the future.

Nowadays, they all lived in the tenement houses near the slums. The heroic-looking Tamonta Onimaru, still unmarried, lived with his sixty-three-year-old mother and eighty-eight-year-old grandmother; Jirōmasa Saruki, who fell into a trance whenever he was counting money, had a wife who ate so prodigiously that she looked like a sumo wrestler; Heisuke Yokomakura, whose philosophy was that the best way is always to do nothing at all, had, unaccountably, seven children; Heikurō Imokawa, who used flattery to cadge money from his colleagues, might have had no wife, but he did have five younger siblings to look after; and the sickly-looking weed Sohachi Ichinohata had a hot-tempered spouse, who at least once a day would strike her husband’s sunken cheeks and send his head spinning.

As chance would have it, only the previous day, they had all got it in the neck from their mothers, come to blows with their wives or been reduced to tears by their siblings and children. And so, to distract themselves, they had all thought of buying a woman—oddly enough, a love of prostitutes was the only thing they shared. For some reason they had ended up placing their faith in Ichinohata, who seemed to be in the money, to make this happen. But when they visited him at the prison, they had been frightened by that odd-looking devil from the Heian-period court, which dampened their ardour—and that was how they had wound up drinking in a backstreet izakaya instead.

‘If things get any worse, we can kiss goodbye to surrounding ourselves with beautiful maiko from Yanagibashi and discussing the great affairs of state,’ drawled Onimaru. ‘Maybe I’ll never hold a beautiful woman in my arms again. My hopes, my dreams—all gone!’

With that, he hung his bearded head over his plate of octopus and began to weep. He was awfully prone to weeping after a drink or two.

‘Can we really be done for?! Unlike you lot, I still have so many things that I want to do. No, not just the women! There are things that I ought to have done as a man.’

‘“Unlike you lot”?! That’s a bit harsh, isn’t it?’ said the lazy Yokomakura, pouting. ‘I have things that I want to do, too!’

‘You?! Such as?’

‘Well, I don’t really know, but still… I just have this feeling that there are things I want to do.’

‘I wish that I could be a man!’ cried Onimaru, tears welling in his eyes. ‘I don’t know how, but I’d like to die having done something that would make people think I’d lived a meaningful life.’

‘Hear, hear!’ shouted Imokawa. Then, after a pause, he got to his feet. ‘This bar isn’t exactly lifting my spirits. Why don’t we all pile down to Yoshiwara anyway?’

Seeing the group clatter towards the exit in a flurry of excitement, the innkeeper quickly called after them.

‘Gentlemen! Your bill!’

‘I’ll settle up with you next time I’m on patrol in the area,’ said Saruki. ‘You can wait until then.’

‘I’m sorry, but that just won’t do. We run a hand-to-mouth sort of establishment.’

Having been bawling his eyes out only a moment before, Onimaru now looked over his shoulder and yelled at the owner: ‘Don’t be absurd! Just who do you think it is who makes it possible for you to run “a hand-to-mouth sort of establishment” in such a treacherous world? Aren’t we the ones who go without sleep, just to keep the likes of you in business?’

6

Having left the izakaya behind, the five rasotsu set off in the direction of Asakusa.

Their arms around each others’ shoulders, the group marched in a line down the lawless, moonlit, already deserted streets, singing a popular ditty of the day at the top of their voices.

Up ahead of them, the shadow of the palace gate at Asakusa drew into view. But just then, somebody came running out of a side alley.

‘Who’s there?’ the figure called out, having heard the singing and stopping it dead. He peered at the group through the moonlight. ‘Oh, sergeants! There’s robbers, I’m being robbed! Help me, please!’

He practically ran into them, falling to the ground and clutching at their ankles.

‘There’s three of them,’ he said in a shrill voice. ‘They had their swords drawn and were threatening me. One false move and they would have killed me. Oh, how glad I am! How happy I am to see you, sergeants! Quickly, now, it’s the Sumiya pawnshop just over there.’

Imokawa shook off his hands.

‘Terribly sorry, but right now we’re on urgent official business. There’s a police station just up there, by the palace gate at Asakusa. Go there, if you want.’

The five of them spun around. They had all sobered up the moment they stopped singing, and so now they marched off with a true sense of urgency.

At the crossroads directly in front of them, however, were two silhouettes, coming towards them and barring their way. Who could they be?

Before they could ask the question, the rasotsu were startled. In the moonlight, they recognized the silhouette of a suikan and also the outline of a fuka-amigasa.

‘Go back!’ said the figure in the suikan.

‘Is there a law that permits rasotsu to run away,’ the man in the fuka-amigasa added, ‘even after being informed that there are bandits around?’

The second man spoke with a Satsuma accent.

‘Turn back!’ he commanded.

The five rasotsu were stunned. They spun around and retraced their steps in confusion.

‘Which one of you was it who told him to go away?’ the man in the fuka-amigasa asked.

‘It… it was me,’ replied Imokawa, trembling.

The man who had approached them earlier was nowhere to be seen. He must have run off to the police station in Asakusa. Leaving the figure in the suikan and the rasotsu where they were, the man in the fuka-amigasa marched off into the alleyway by himself.

Moments later, he returned and said, ‘All right. It’s the pawnshop five or six doors down. The only way out is through this alley.’

‘Kazuki, would you flush them out? I’ll wait here and shoot them when they come running.’

From the breast of his kimono he extracted something that astonished the rasotsu: a pistol.

‘No, wait! We don’t want to kill them,’ said the man in the suikan with a shake of his head. ‘I need them alive. Better you shoot the pistol here. The bandits will come flying out and down the alley. That’s where I’ll catch them.’

‘Are you sure that’s best?’

‘I think so.’

When they saw the object that he drew from his waist, the rasotsu were wide-eyed in amazement. It was not a sword, but the folded cypress-wood fan that they had seen earlier that afternoon.

Then, his furred boots muffling his footsteps, he entered the alley.

Rather than ask how on earth he was going to arrest the bandits with only a fan, the rasotsu—and especially Imokawa—could not resist asking a question that had been plaguing them from the outset.

‘Sir,’ they called out to the samurai wearing the fuka-amigasa. ‘Who on earth are you?’

‘I’m Chief Inspector Toshiyoshi Kawaji,’ the man replied, ‘of the Imperial Prosecuting Office.’

He raised the arm in which he was holding the pistol.

Down in the alley, the cypress-wood fan opened with a flourish.

‘Excellent!’

The blast of the gun rent the moonlit sky.

A few moments later, a tangle of figures appeared in the alleyway. They peered out of the darkness into the street, then gave a cry of alarm, and hastily beat a retreat, before stopping dead in their tracks.

The rasotsu saw the flash of several swords being drawn, a flurry of movement, then all was still.

‘Over here!’ called the figure in the suikan, stepping out of the shadows.

Seeing him stand there on his own, the rasotsu were taken aback.

Drawn by the sound of gunfire, locals began appearing from all over, curious to find out what the commotion was. When they saw the fantastic vision of a Heian courtier, seemingly floating before them in a moonlight-drenched Tokyo alleyway, they stopped, spellbound.

‘There’s no cause for alarm,’ said the figure in the suikan, slowly undulating his cypress-wood fan. ‘The robbers have been dealt with.’

When the five rasotsu came running, he pointed with his fan to the three silhouettes lying at his feet.

‘Take them into custody.’

7

It was to be a night of surprises.

The first surprise was that the young man from the Imperial Prosecuting Office, using only his fan, had seemingly made the three robbers faint with fear. The fan was made entirely of thin strips of cypress, and since it was almost a foot and a half long, it could be used as a baton when folded, but the rasotsu were unaware of this, and, even if they had known, it would still have stunned them to learn that he could defeat three sword-wielding robbers with it.

The second surprise was that among the robbers there was a woman in her thirties, which they did not immediately realize on account of her wearing a mask and a man’s kimono. Lifting up the three figures who had been knocked unconscious, the rasotsu either slung them over their shoulders or dragged them by their hands and feet to the jail in Kodenma-chō, where the third surprise awaited them.

After arriving at the prison, they were all herded into a cell of their own.

‘Hey! What’s all this?’ they protested, panic-stricken.

‘No idea,’ replied the guard on the other side of the bars. ‘Chief Inspector’s orders.’

Naturally, it had come as a quite surprise to them to learn that the samurai in the fuka-amigasa was also a chief inspector, and that he was a colleague of that devil in Heian garb.

‘But in that case,’ Imokawa muttered, looking worried, ‘maybe the chief inspector has been following me all this time! Maybe they’ve been following all of us!’

The other four turned pale.

‘Do you think that’s why we’ve been thrown in here?’ asked Saruki, cradling his head in his hands.

‘But wasn’t Ichinohata let off the hook after he was taken to task by that Western scholar this afternoon?’ asked Yokomakura. ‘Besides, all rasotsu do this sort of thing. Why are we the only ones being locked up?’

Whatever the reason, the fact remained: they had been thrown behind bars, which did nothing to relieve their anxiety.

‘So, might the two chief inspectors be around?’ Onimaru asked the guard.

‘They might,’ the guard replied, before adding: ‘They appear to be doing something at the execution ground.’

The five rasotsu looked at one another.

‘In the dead of the night?’ asked Ichinohata, his voice hoarse.

‘Mmm-hmm… Oh, and just a little while ago, somebody arrived by palanquin. Apparently, the chief inspectors summoned him.’

‘What?!’

Their anxiety levels shot up.

‘Who is it?’

‘I’ve no idea, but he was shown, still in his palanquin, straight to the execution ground. Ah yes, about those three robbers you brought in earlier,’ said the guard, changing the subject. ‘They were some pretty big fish, you know. One is Wild Dog Kinbei, another is Scarface Taji, and the third is Ballbreaker O-Aya.’

‘Never heard of them.’

‘You’re all pretty new around here, so it’s only to be expected,’ the guard said. He had served there as a guard since the old days.

‘I don’t know how many people they must have killed. They were the most feared gang we had here, but they were let out under the new regime. Don’t ask me why. But, hey, you did good catching them again.’

‘Hey! Maybe they’re going to be executed,’ Imokawa suggested.

‘Hmm, I doubt they’d do it at this time of night.’

‘So do I,’ added Ichinohata, who knew the place well. ‘I’ve never heard of them carrying out an execution in the dead of night. In fact, I may as well tell you: one of my jobs here is to deal with the bodies after the beheadings.’

The four others stared at Ichinohata in horror.

Nobody dared joke whether he would be ‘dealing with’ his own corpse that night.

It was about half an hour later that several prison officials arrived and the rasotsu were conducted from their cell to the execution ground. Needless to say, this sent the five into a terrible panic.

Terrified by the sound of jeering voices, they all began to tremble. Saruki, for one, failed to spot that one of his enormous shoes had slipped off, while the heroic-looking Onimaru seemed to suffer a fit of cerebral anaemia and went crashing to the ground. In the end, the prison guards had to prop him up on both sides.

After passing through several wooden doors, they saw that the night sky ahead of them was aglow. Something was burning down below.

‘What’s that fire?’

‘I’ve no idea. But that’s the execution ground over there,’ answered Ichinohata, his teeth chattering.

Eventually, they arrived in front of a small gate cut into a mud wall. A palanquin had been set down beside it, but the rasotsu didn’t even have the time to realize that this must be the one the guard had told them about.

‘You’re ordered to go through,’ the guard said. ‘Quickly, now.’

The door opened and through they went.

Then the door closed behind them.

8

What awaited the already half-dead rasotsu on the other side was a scene that could have been dreamt up only in the hereafter.

The execution ground was enclosed by a mud wall that was cracked and crumbling all over, and, right in the centre of the square, four bonfires were burning. These were what was turning the night sky red. Staked in the ground beside them were canes of green bamboo with their leaves still on them, bound together by the kind of rope ordinarily reserved for Shinto ceremonies, with the zigzag paper streamers attached to the rope fluttering in the wind.

In the middle of the square, a three-tier scaffold had been erected, upon which stood two solid-looking pillars side by side, twice the height of any man, with just enough space between them for somebody to pass through. They were connected at the top by a thick board—but what was that thing attached to the board?

The object was glittering a bright red in the light cast by the bonfires. Plainly, it was an iron blade, and it was slanting downwards. There was another board at the bottom of the two pillars, with a square basket fixed to the nearest side of it. There was also a rope dangling from the top of the structure.