Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nosy Crow Ltd

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

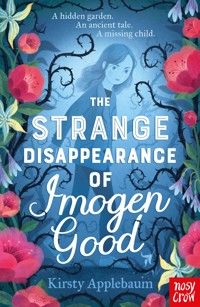

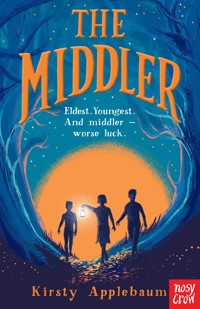

"I was special. I was a hero. I lost the best friend I ever had." Eleven-year-old Maggie lives in Fennis Wick, enclosed and protected from the outside world by a boundary, beyond which the Quiet War rages and the dirty, dangerous wanderers roam. Her brother Jed is an eldest, revered and special. A hero. Her younger brother is Trig - everyone loves Trig. But Maggie's just a middler; invisible and left behind. Then, one hot September day, she meets Una, a hungry wanderer girl in need of help, and everything Maggie has ever known gets turned on its head. Narrated expertly and often hilariously by Maggie, we experience the trials and frustrations of being the forgotten middle child, the child with no voice, even in her own family. This gripping story of forbidden friendship, loyalty and betrayal is perfect for fans of Malorie Blackman, Meg Rosoff, Frances Hardinge and Margaret Atwood. "I thought I'd almost reached my fill of dystopian novels, but Kirsty Applebaum has rebooted the genre. The plot pulls you along and I liked Maggie more and more as she grew in courage. There is a touch of Harper Lee's Scout about her." - Alex O'Connell, The Times Also by Kirsty Applebaum: TrooFriend

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 234

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Jacqui C.

PROLOGUE

Our eldest, Jed, got born first out of all of us.

Our youngest, Trig – he got born four years later.

And me, Maggie, I was in-between. The middler, worse luck.

MONDAY 1 SEPTEMBER

CHAPTER 1

I took my summer diary out of my drawer. Nearly all the sheets of paper matched. On the very last page I’d drawn a picture of a red admiral. It had black wings and bright red stripes, just like the ones we’d seen up at the butterfly fields.

I straightened the yellow wool bow that held it all together and ran my hands over the front to flatten it down. I wouldn’t win Best Diary – an eldest always wins that – but maybe I could get runner-up.

I carried it downstairs.

“You ready, Mags?” Trig had the front door open and was leaning right out of it, both hands gripping the door frame. His diary was on the doormat, tied up with garden string. “We should’ve left already. Shouldn’t we, Dad? We should’ve left.”

“Oh, Maggie.” Dad shook his head at my legs. “We really need to do something about that uniform. It’s even shorter than it was before the holidays.”

He yanked at the bottom of my dress. It shrugged back up again.

“Jed! Jed! Jed!” Trig was turning red with all his shouting.

“Just a minute!” Jed’s voice echoed down the stairs.

Mum came out of the kitchen, booted up for a day in the fields. “Leave without him,” she said. “It’s his own fault if he’s late.”

“C’mon, Maggie.” Trig picked up his diary but I wasn’t going anywhere till Jed was with us.

Eventually he appeared, shirt hanging out and jam on his chin.

“Did you remember your summer diary?” said Trig.

“S’in here.” Jed turned round and patted his back pocket. His messy, folded pages flapped out of the top.

Dad went to wipe the jam off Jed’s face, but he ducked under his arm and we all ran through the door into the warm September air.

Trig was hopeless at running. He held his diary right out in front of him all the way to school. Me and Jed had to stop at every corner for him to catch up.

“Good morning, Mrs Zimmerman;

Good morning, Mr Temple;

Good morning, Miss Conteh;

Good morning, Mr Webster;

Good morning, EVERYONE.”

The school hall smelled like the beginning of term. Wood oil and scouring powder.

“Smells weird. Doesn’t it, Maggie? Doesn’t it, Jed? Smells weird.” Trig fidgeted and scrunched up his nose.

“Shhh,” I said.

Lindi Chowdhry was in front of us, all cross-legged and straight-backed and long-haired. Her dress had a new frill sewn round the hem. Jed scooted forwards so he was sitting closer to her.

Mrs Zimmerman clasped her hands together in front of her waist. “Mr Webster has kindly spent part of his summer sanding and oiling our hall floor. Aren’t we lucky?”

I spread out my fingers and pressed my palms on to the smooth wood. Must’ve taken him ages.

“Heads down, please, for the morning chant.”

“Our eldests are heroes.

Our eldests are special.

Our eldests are brave.

Shame upon any who holds back an eldest

And shame upon their kin.

Most of all,

Shame upon the wanderers.

Let peace settle over the Quiet War,

Truly and forever.”

Mrs Zimmerman lifted her head, tilted it to one side, and smiled. “Welcome back to Fennis Wick School, everyone. I hope you enjoyed your break.”

We bit at our nails and gazed up at the empty walls while she said all the things that head teachers have to say at the beginning of term.

“As well as sanding the floorboards, Mr Webster has also dug over the toilets for us. Please be sure to use the new ones and leave the old ones to compost. He’s left everything very clearly signposted.”

We clapped for Mr Webster.

“Miss Conteh has returned to us after having her baby – a little boy, called Michael. An eldest. We’re hoping his dad might pop in with him one lunchtime.”

We clapped for Miss Conteh.

“Two of our pupils, Sally Owens and Deb Merino – both eldests, of course – turned fourteen over the summer and have gone to camp.”

We clapped for Sally Owens.

We clapped for Deb Merino.

“And two more of our eldests are heading off for camp this very Saturday – Jed Cruise and Lindi Chowdhry.”

Jed leaned in and nudged shoulders with Lindi.

My hands were getting fed up with all the clapping.

“And just before we return to our classes, we have a special guest here today with some important news.” Mrs Zimmerman held out an arm towards the entrance of the hall.

No one came out.

“Er … we have a special guest here with some important news,” she said again, louder this time.

No one came out.

Mr Temple cleared his throat. He nodded towards the window.

Mayor Anderson was sitting on the wall in the littlests’ outdoor play area, feet resting on a go-fast-kart and two hands cupped round an enormous butty. Cheese, by the look of it. She finished up chewing, swallowed her mouthful, and gave us a wave.

A few of us waved back.

Mrs Zimmerman took a deep breath in. “Would you be so kind as to let the mayor know we’re ready for her, Mr Temple?”

“O-K.” Mayor Anderson stood in the middle of Mr Webster’s newly oiled floor, her hair drawn back in a straggly ponytail. “I’m not going to beat around the bush and do all that what have you learned over the summer rubbish. I’ll leave that to your teachers, eh?” She gave us a wink and got a few sniggers back from the audience.

Mrs Zimmerman closed her eyes.

“But what I am going to do,” the mayor went on, “is tell you we’ve heard reports of wanderers five miles south of the town boundary.”

Wanderers?

The sniggering stopped.

Mrs Zimmerman opened her eyes.

A shiver crept across my shoulders.

“Yep.” Mayor Anderson nodded. “Yesterday I was up at the city. Met with some colleagues. It’s been a while since we had wanderers in our area but their numbers appear to be increasing.” She took a slow moment to look from one side of the hall to the other, catching as many of our eyes as she could.

“So,” she carried on, “why do we not want wanderers nearby? Anyone?”

Trig stuck his arm up as high as he could get it. Pushed it even higher with his other hand. Mayor Anderson couldn’t miss him.

“Go on then – tell us, Trig.”

“They’re … er…” Trig looked up to the ceiling, the way you do when you’re trying hard to remember something. “Dirty, dangerous and … deceitful.”

“Dirty. Dangerous. Deceitful.” Mayor Anderson boomed the words back at us, counting them off on her fingers. “And to think,” she said, “that they’re supposed to be on our side in this war.”

She clasped her hands behind her and swayed backwards and forwards with her feet stopped still. “Our country is one of the few places – perhaps even the only place – that has kept the enemy at bay. Why is that, do you think?”

Trig stuck his hand up again.

“Our geography has helped, for sure.” Mayor Anderson nodded at Trig, like he’d given her the answer even though he hadn’t. “Along with our land’s wonderful capacity for self-sufficiency.” She nodded some more. “But the real reason our country survives is us. Our very selves.” She held her arms wide. “We are an adaptable people. Stoic. Brave. We understand the importance of hard work and sacrifice for a greater good. We have a long history of wartime resilience. It’s in our blood. And the bravest of us all, of course, are our eldests.”

She looked at Jed and Lindy. They nudged shoulders again.

“At camp,” said Mayor Anderson, “our eldests join the Quiet War. They fight valiantly. They fight heroically. They fight so that we, back home, can remain safe. My one and only child, Caroline, went to camp ten years ago this very month. I couldn’t be more proud.”

We clapped for Caroline.

The mayor held up a hand.

“But,” she said, “the wanderers do not send their eldests to camp.” She did a slow shake of her head. “They are protected from the enemy by our brave heroes – but they selfishly keep their own eldests close. They disobey Andrew Solsbury’s edict that decrees we must ALL send our eldests to camp. They deny their families the opportunity to live in a town in a civilised manner, and they deny their eldests the opportunity to fight for their country. They are dirty, dangerous and deceitful. Do we want their kind anywhere near us, here in Fennis Wick?”

“No, Mayor Anderson.” We shook our heads.

“And more than that —” the mayor leaned in towards us and lowered her voice to a whisper — “much more than that – you’re aware of the horror wreaked by wanderers the last time they ventured close to Fennis Wick. My own sister was among the casualties.”

She dropped her eyes to the floor.

A littlest at the front began to cry.

Trig’s knees started jiggling.

“So.” The mayor took a deep breath and lifted her head. “What can we do to keep ourselves safe? What’s the most important rule of all?”

“Never go beyond the boundary!” Trig burst out the answer.

“Abso-bloomin-lutely, Trig Cruise. Never go beyond the boundary. Follow that rule and you’ll be safe from wanderers. Remember: dirty, dangerous, deceitful. All right?”

“Yes, Mayor Anderson,” we nodded.

She smiled. One of those smiles where the sides of your mouth go down instead of up.

“So how about we sing the boundary song to finish?” Mayor Anderson rubbed her hands together. “Mr Temple? Would you accompany us on the old piano? Still working, is it?”

Mr Temple lifted the lid of the piano. He interlaced his fingers and turned them inside out. The clicking echoed all around the hall.

“Oh – a quick reminder before we start singing.” Mayor Anderson wasn’t smiling any more. She ran her tongue across the front of her teeth. “Going beyond a town boundary isn’t only a risk to yourself – it puts the whole of Fennis Wick in danger. Your friends, your family, your neighbours. And anyone who puts Fennis Wick in danger could be subject to a very serious punishment indeed. So let’s keep everyone safe, eh? Now, carry on, Mr Temple.”

The crying littlest cried even louder.

Back in the classroom Miss Conteh talked about the time before the Quiet War and what summer holidays were like then. She said people used to go to other countries on aeroplanes. I doodled a picture of an aeroplane in the bottom corner of my slate. Licked my finger and rubbed it off.

Sometimes I wondered if teachers didn’t just make stuff up.

After break Miss Conteh asked for our summer diaries. She walked between the desks, collecting them in and piling them up in her arms.

“I’ll be reading through these this afternoon,” she said, “and tomorrow I’ll announce the winners.”

I passed her mine, taking care to keep the bow straight.

“Thank you, Maddie.”

Maddie?

Lindi laughed. “It’s Maggie, Miss Conteh, not Maddie.”

“Oh, of course it is. Sorry, Maggie, the baby had me up four times last night.”

She put my diary on the pile, then stuck six more right on top of it, squashing the bow.

CHAPTER 2

After school we changed out of our uniforms and went up to the cemetery, right out near the hawthorn boundary. Hunting for wanderers.

It was Jed’s idea.

“Come on,” he called down. “Who’s coming up next?”

He was balanced in the tallest tree, legs dappled by the leaves and the sun. Looked like he was wearing camouflage. The branches rippled in the heat.

Me and Trig and Lindi all squinted up.

“Look.” Jed pointed south, past the red-berried hawthorn. Grandad Cruise’s watch glinted on his wrist. “I can see for miles.”

My heart kerdunk-kerdunk-kerdunked under my T-shirt.

“Can you see any wanderers?” Trig shaded his eyes with both hands.

“Course not, not yet,” said Jed. “We’ve got to watch and wait.”

He was really high. My stomach swirled just looking at him.

“D’you think the mayor’ll give us a reward?” I shaded my eyes too. “Y’know, if we find one? Will she read our names out in assembly?”

Jed laughed. “You’re never going to spot one, Maggie. You’re just a middler. You’re too scared to even climb up here.”

“Yeah, you’re always too scared of everything.” Lindi elbowed me and Trig out of the way. “Watch out, Jed. I’m coming up next.”

Jed grinned. It was his idea of heaven, sitting on a branch with Lindi all to himself.

She walked between the two graves set under the tree. The headstones had ancient names carved into them: William Whittington and Georgina Millicent Cruise. Georgina Millicent Cruise was my great-great-great-great-grandmother. Funny how the cemetery smelled of grass and soil and sap-laden trees when actually we were surrounded by old, dead relatives.

Lindi got a knotty handhold on the trunk and found somewhere to put her first foot. She pulled herself up and found a second foothold, then a third, a fourth, a fifth. She didn’t have shorts on like me. She was wearing a stupid white dress that showed her underwear if she even just climbed over a stile.

She was nearly up to Jed. My mouth went dry.

They were right – I was scared. Of climbing. Of hunting for wanderers. Of everything. So what, though? So what? We were never going to find one anyway.

Jed held out his hand to Lindi. She grabbed it. She leaned away from the trunk and let go with her other hand.

Her foot slipped on the dry bark.

Their hands slid apart.

Her stupid dress blew up around her waist.

She bounced head first off the William Whittington gravestone and landed on the ground, blood all over her face.

She lay there, still as you like.

The sound her head made on the gravestone replayed itself in my ears. Crunck. Like being whacked with a brick. Crunck.

Her pants were white, with little blue flowers on them. Forget-me-nots. I stepped forwards and pulled her dress down. It wasn’t right for the boys to be seeing all that.

No one screamed. No one shouted. Jed said something unrepeatable, but he said it really quiet, like his voice had been squashed by the shock. Then he half scrambled, half jumped down from the tree. He tried pulling Lindi up but he couldn’t lift her. Her blood got all over his hands. He pushed his hair out of his eyes and left a messy red stripe across the side of his head.

“Lindi,” he said in his squashed voice. “Lindi. Lindi. Lindi.”

“She’s dead,” I said.

“No she’s not; she can’t be,” said Jed. “We have to do something.”

And we stood there, all three of us Cruise kids, looking down at Lindi Chowdhry with her white dress and her bloody face and her long dark hair spread out on the grass.

“You have to check if she’s breathing.” It was Trig – Trig who can’t even hop or run or tie proper reef knots. “If she’s not, you have to breathe for her. First aid. We did it in school, remember? Ages ago.” He swallowed. “And one of us has to run for help.”

Jed knelt down next to Lindi. “I’m not leaving her. You go, Maggie.”

Me?

“Quick, Maggie – you gotta run.”

So I ran.

I ran through the cemetery, leaping over the old Parker graves and the Stanbury ones too, grass whipping at my ankles. I ran all down the edge of Anderson’s field. Tiny black thunderbugs flew into my eyes but I didn’t stop to scrape them out, I just blinked and kept running. At the bottom of the field I jumped over the sun-dried mud ridges and didn’t trip even once. I skimmed round the side of the old caravan park south of the town, all the time shouting.

“Help! Help! Doctor Sunita!”

I gasped gobfuls of hot, woolly air. I shouted for Mrs Chowdhry too.

“Mrs Chowdhry! Mrs Chowdhry!”

I leapt across the allotments, between courgettes, rhubarb, tomatoes.

“What is it, girl?”

I stopped so quick I nearly fell over.

It was Elsie Weather, kneeling in the strawberry beds. Just my luck.

“What is it, girl? What’s wrong?” She used her stick to help her up. She had two old sponges strapped to her knees with elastic bands.

“It’s Lindi, Lindi Chowdhry. I need to get help.”

“Wait, girl. Perhaps old Elsie can be of use.” She brushed some earth off her knee sponges.

“I have to be quick. Lindi hit her head. She fell out of a tree. She’s not moving.” I clattered out sentences in the wrong order, glancing over towards the town.

Elsie Weather swapped her stick from one unsteady hand to the other, reached into her pocket and brought out a hanky. She coughed into it, like she was coughing up her insides. My legs quivered, ready to run.

“Lindi Chowdhry.” She refolded her hanky. Her fingernails were thick and yellow. “An eldest, isn’t she?”

The sun spilled over Elsie’s shoulder straight into my eyes. “Yes, but – I’ve got to hurry, Mrs Weather. I’ve got to go.”

“Wait, Cruise girl.” She reached forwards and grabbed my hand. “How old is she, this Lindi?”

Her thumb bone pressed hard into my palm. I tried to pull away.

“How long till she goes to camp?”

“Mrs Weather, I don’t have time.”

She pulled me towards her. Breathed into my face. I coughed.

“How old is she? How long till she goes to camp?”

It was Lindi’s fourteenth two nights ago. Everyone was there, even Elsie. She can’t have forgotten, can she?

“She’s fourteen. She’s going on Saturday.” I pulled my hand away, right out of her grip. Her thumbnail scraped my skin. “I’m sorry, Mrs Weather, I’ve got to go. I’m sorry.”

“Storm’s coming,” she called out after me.

I ran. Away from Elsie, away from the caravans, over to the town.

The Parker brothers were coming out of Frog Alley. Robbie, Neel, Grif and Lyle, all thick beards and rolled-up sleeves.

“Help!” I called out. “Help! We need help!”

CHAPTER 3

Robbie Parker knelt down and put his ear close to Lindi’s mouth. Like she was whispering something he wanted to hear.

“She’s breathing,” said Jed. “Trig checked. Then he rolled her on to her side—”

“So she wouldn’t choke,” said Trig.

I squatted on the ground, not too close. Lindi’s dress had green stains on it from the grass and red ones from her blood. They’d be a job to get out.

“You did well,” Robbie said.

Was he talking to Trig? Jed? Me? He didn’t take his eyes off Lindi. He slid an arm under her shoulder, pushing through her hair. His brother, Neel, cupped her head in his hands. Then Robbie tucked his other arm under her legs, rocked her towards him and stood up. Lindi hung pelt-like between his arms.

They carried her back across the cemetery – slowly, steadily – the way you’d walk if you were fetching mugs of milk that’ve been filled up too high.

“What were you lot doing all the way up here anyway? Not making trouble, I hope?” Lyle Parker took a pair of glasses out of his shirt pocket and put them on. The glass bit – the bit you look through – was dark.

“No.” We stared. How could he even see?

“Showing off your present from the mayor, Lyle?” said Grif. “Trying to impress a bunch of schoolkids? No stopping you, is there?”

“Shut up, Grif.” Lyle looked at Jed. “You’re an eldest, aren’t you?”

“Yeah,” said Jed.

“C’mon then. Walk back with us.”

They started off after the others.

They sang as they walked.

“In the northside fields where the daisies grow

I found my love, sweet Evie-oh

With her jet-black skin and her jet-black curls

Under the shadow of the grey willow.”

“Grey Willow”. We’d heard it a million times before. The way the Parkers sang it, though, it was like it was a whole new song. Like it wasn’t just a song – it was real. Maybe it wasn’t really the Parkers singing at all. Maybe it was the dead relatives – William Whittington and Georgina Millicent Cruise and all the other dead Andersons and Cruises and Stanburys and Parkers – everyone who’d ever died and got buried in Fennis Wick cemetery.

They sang it soft and strong and dark and smooth.

“She took off for camp with her billy lamp

Under the shadow of the grey willow.”

Me and Trig tagged behind, singing along under our breath.

The Parkers carried Lindi into Frog Alley. They disappeared between the houses, heading for Doctor Sunita’s. Jed went with them, but me and Trig just sort of stopped at the entrance of the alley.

I scanned around for frogs, but there weren’t any. A fat black caterpillar curled along the brickwork. I held my finger in front of it, but it wouldn’t climb on. It arched its middle, wiggled round, and crawled along in the other direction. Slow as you like. Funny how, somewhere inside it, there’s the beginnings of wings.

I prodded it. It fell off into the stinging nettles.

I looked back out towards the caravans. Elsie Weather was still there, kneeling down on her sponges in the strawberry beds.

It was extra quiet now. We couldn’t hear the singing any more.

I leaned against the wall. It was scratchy behind me. I pressed the back of my head into the bricks. What would it be like if I cracked it against them really hard?

What would it be like if I got knocked unconscious, like Lindi?

What would it be like if I died?

I closed my eyes and held my breath. Would it feel like this?

“D’you think Lindi’ll be all right?” Trig flapped around the alley, all too-big hands and too-big feet. “D’you think Doctor Sunita can save her? D’you think Lyle can see out of those funny glasses? He’s so lucky the mayor gets him special presents. It didn’t look like he could see out of them, did—”

He stopped still. His mouth went into a full-blown “O” shape.

“Oh no,” he said. “Oh no!”

“What? What is it, Trig?”

“I left my jumper behind. My grey one. Up at the cemetery. Right near the tree.”

“Oh, Trig. It’s boiling. Why d’you bring a jumper out anyway? It’s been boiling for weeks.”

“Sorry.” Trig stuck his hands into his pockets. His head dropped down between his shoulders. “I’ll go and get it.”

Mr Wetheral’s Siamese cat skulked past with a dead frog hanging out of its mouth.

“S’all right, Trig,” I said. “You go home. I’ll get the jumper. I’ll be quicker.”

He chucked his arms round me and squeezed. A proper Trig-hug.

The jumper wasn’t there.

I went round the tree. I went round William Whittington and Georgina Millicent Cruise. I went round the whole blooming graveyard. It wasn’t there.

Maybe he’d got mixed up. Maybe he’d left it somewhere else. Typical Trig.

Just one last look behind the gravestones again.

“Hey!”

What was that?

“Hey!”

It wasn’t a shout. More of a really loud whisper.

“Hey!”

Yes. A loud whisper. Like whoever was saying it half wanted to be heard and half didn’t.

“Here! Over here!”

It was coming from the hawthorn hedge. The boundary.

Hedges don’t whisper on their own. Hedges don’t whisper unless someone’s hiding on the other side of them.

A head peeped out through the thinnest part of the greenery. A girl’s head. With hair the exact same yellow as a pound-cake mixture right before you bake it.

I knew all the kids in our town. Been at school with them since I was knee-high. None of us had hair that colour. And none of us would hide on the wrong side of a town boundary. Not ever.

She was a wanderer.

My heart paused.

My breath stopped.

Dirty. Dangerous. Deceitful.

“You looking for something?” She squeezed through the hedge and stood up all foal-like on long, skinny legs.

She was wearing a raggedy brown dress, a pair of wellies that might have been red once, and Trig’s grey jumper.

CHAPTER 4

The girl grinned. There was a big gap between her two front teeth.

“Is she all right?” She tucked her pound-cake hair behind her ears. It fell straight back out again. “The one who fell out of the tree. Is she all right?”

She’d been watching us. All the time we were there.

“It’s just you here now, isn’t it? The others are gone?” she said.

I looked back towards the town. Too far away to see anyone. Too far away for anyone to hear a shout for help.

“You looking for this?” She pulled the front of the jumper away from her chest.

Mum’d go mad if we lost Trig’s jumper. He’d only got two.

“I’m Una. Una Opal.” She stuck out her hand.

I stepped backwards.

“You can have your jumper,” she said. “I’ll give it to you.”

She didn’t take it off, though.

“I need some help first. That’s all.” She tucked her hair behind her ears again. It fell back out again. “I need you to get some food. For me and my dad. And antibiotics. He’s got a bad leg, see? If you get me some food and some antibiotics, I’ll give you your jumper.”

I took another step backwards and tripped over a gravestone. I scrabbled myself back to upright.

“Oh,” she said, “are you OK?”

There was a look on her face, like she was worried about me. Worried I’d hurt myself. She wasn’t, though. She couldn’t be. She was a wanderer. It was just her being deceitful.

“I didn’t mean to scare you,” she said. “I just meant to – I don’t know. Oh heck, I’m hopeless at this, aren’t I?” She took a deep breath in and sighed it out again, big and loud.

“Here, just have the jumper.” She grabbed it from the bottom and pulled it up over her head. She didn’t hold it out or anything, though. She just twisted it in her dirty wanderer hands. “Will you still help me?”

The air was heavy. Hard to breathe.

“Or if you can’t help me, just promise you won’t tell anyone else you saw me?” She clutched the jumper to her chest. Her eyes went shiny. Like when you’re trying not to cry.

Did wanderers cry?

“Promise?” she said.

I nodded my head. Just a tiny bit. So tiny it wasn’t even really a nod at all. And it didn’t really count as a proper promise, did it? Not if it was made to a wanderer.

She threw the jumper gently towards me. It landed on the ground between us. I darted forwards, snatched it away and ran as fast as I could back towards Anderson’s field. I ran all the way to town for the second time that day. Didn’t stop until I got to the allotments.

I bent over and heaved in lungfuls of strawberry-sweet air. Had anyone seen me? Did they know what had happened?

No. There was no one around.

No one except Elsie, crouched down between the rhubarb leaves.

CHAPTER 5

I crashed through the front door.

“Dad! Dad! Listen, I’ve just been—”