Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Lightning Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

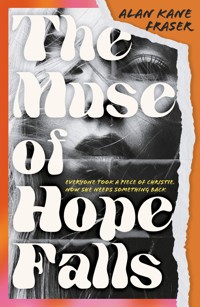

Everyone took a piece of Christie. Now she needs something back. As the muse and lover of one of the greatest painters of the late 20th century, Christie McGraw was once a major figure in New York. Now penniless, abandoned, and sick, she needs to sell the last thing of any value that is still in her possession. It's a lost masterpiece by her late lover, and she needs the help of Gabriel Viejo, the world expert on the artist, to authenticate it and get into the market. If he can help, she'll make it well worth his while. Gabriel opens negotiations with a shady Greek tycoon in the hope of saving Christie's life – and boosting his own fortunes into the bargain. But there are some nasty surprises in store. Alan Kane Fraser's devilishly devious debut is a page-turning plunge into the murkier depths of the art world and the age-old relationship between creator and muse.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 442

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Praise for The Muse of Hope Falls

‘Expert storytelling, clever plotting and convincing characters make this not only an absorbing and highly entertaining tale, but also a thought-provoking reflection on the truths that art can tell, or hide’

Hilary Taylor

‘A glorious caper – full of humour, engaging characters and infatuation. A thoroughly enjoyable read’

Nicky Downes

‘A brilliantly funny and twisting plot, driven by real, eccentric characters. You feel like you’re in the room with them, and you wouldn’t want to be anywhere else’

Tim Ewins

‘A witty, well-written novel exploring the world of painting, modelling and art-as-commodity, with an unexpected criminal caper at its heart. An exuberant debut that is both fun and thoughtful’

Richard Francis

‘Alan Kane Fraser’s beautiful work about life the other side of the easel – its impact, its anonymity, the inevitable betrayal – both compels and disturbs. He has that unusual ability of allowing characters to collide whilst not being a devotee of either’

Jeff Weston

ALAN KANE FRASER was raised in Handsworth, Birmingham, in the era when that district was famous for its riots. He has been variously a priest, a housing officer and a charity CEO, in which capacity he wrote for a number of publications, including the Guardian. He is also the author of an award-winning play, Random Acts of Malice.

He still lives in Birmingham, with his wife and a woefully inadequate number of bookshelves.

Published in 2023

by Lightning Books

Imprint of Eye Books Ltd

29A Barrow Street

Much Wenlock

Shropshire

TF13 6EN

www.lightning-books.com

Copyright © Alan Kane Fraser 2023

Cover design by Nell Wood

Typeset in Dante MT Std and Flood Std

The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 9781785633744

For Fiona Walker, (‘Tennis Girl’) and Elizabeth Siddal, both of whom inspired this story in different ways

And in loving memory of Carol Poole

For the early Coke executive Robert Woodruff, who said that ‘Coca-Cola should always be within an arm’s reach of desire’, Coke represents the eternally unsatisfied emptiness we seek to fill with something ungraspable A.S. Hamrah,The Paris Review

Contents

PART 1: SUSANNA & THE ELDERS

PART 2: SATURN DEVOURING HIS YOUNG

PART 3: JUDITH BEHEADS HOLOFERNES

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Also from Lightning Books

PART 1

SUSANNA & THE ELDERS

SEPTEMBER 2019, HOPE FALLS, NEW YORK

It’s hard to be a diamond in a rhinestone worldDolly Parton

ONE

I first met the wild and impenetrable gaze of Christie McGraw when I saw her one evening, half-naked, at a gallery on Cork Street. It was sixteen years ago, and I’d been sent to cover the opening of an Erik von Holunder retrospective at the Redfern.

‘Wow! Who the hell is that, I wonder?’ I’d asked rhetorically, while standing in front of 1978’s Bikini-Girl Gunslinger.

‘Judy McGraw,’ Suzy said. ‘But Von Holunder insisted on calling her Christie. Said she looked more like a Christie than a Judy.’

‘I guess I can see that,’ I said. The only Judy I could think of was Judy Garland and Christie certainly didn’t look like her. There was something about Christie’s stare that made demands of you, rather than suggesting that you might make demands of her. It was unnerving but undoubtedly energised the paintings in which she appeared.

‘Anyway, that’s the name that made her famous, so that’s what she got stuck with.’ Suzy turned to look at me. ‘Did you not know that?’

I sensed the first trace of disappointment in her voice. This was a sensation with which I was to become wearyingly familiar over the next thirteen years, and perhaps I should’ve taken it as a warning of what was to come, but that night it was sickeningly new. Suzy’s final-year dissertation was something to do with the representation of women as objects of desire in twentieth-century art. Her tutor had suggested that Erik’s portrayal of Christie represented an interesting counterpoint to the portrayal of Walburga Neuzil in the paintings of Egon Schiele, so she considered herself a bit of an authority. But back then I knew almost nothing about Von Holunder. After that fateful press night though, in a desperate attempt to win back Suzy’s respect, I resolved to become an expert in the life and works of Erik von Holunder, and I like to think I did. Yet as I walked up and knocked on the door of Christie’s residential trailer in a long-forgotten corner of New York fifteen years (and one divorce) later, I still felt like I knew nothing definite about his thrilling and captivating muse.

‘I was expecting a girl,’ she said, eyeing me with suspicion. She was in her late sixties by then, and I had anticipated being welcomed by a white-haired retiree, her face creased with regrets. But to my surprise she retained the statuesque beauty that had first transfixed viewers when she’d stared out defiantly at them from the frame of 1975’s If All the World Was Like Your Smile.

‘I get that a lot, but that would be Gabrielle. I’m Gabriel.’ I offered her my hand. ‘Gabe Viejo.’

She declined to shake it.

‘Have you got some ID?’

I still had an NUJ card, courtesy of my reviews for The Art Newspaper, so I offered her that. She took it from me and examined it sceptically at arm’s length while I waited outside.

‘If you need to get your glasses, that’s fine,’ I said in an attempt to be helpful. Big mistake.

‘I will have you know, young man, there’s nothing wrong with my eyes,’ she snapped. ‘I just need longer arms.’

Despite this, she disappeared back inside her trailer, taking my ID with her.

I turned my head and looked around the rest of the trailer park while I waited. It was called, without apparent irony, Hope Falls.

It was just a few days from the end of September and the weather had begun to turn. A dull drizzle fell wearily from a slate-grey sky, low cloud blanketing the whole of Hope Falls in a gloomy shroud. What could still be seen seemed to have been slowly falling apart for years until now it resembled a Cubist parody of a low-income trailer park. The trailers themselves were patched up like wounded soldiers, their awnings concertinaed like the ruffles on an ugly ante bellum ballgown. Any sense that this place might really be the low-cost housing choice for the discerning professional, as the hoarding at the entrance had, rather optimistically, sought to proclaim, had long since disappeared. Now the name felt like a sick joke. Hope had not just fallen; it had died a slow and lingering death here.

‘Well, I guess you might as well come in,’ Christie said, returning to the doorway and handing me back my card, a pair of half-lune glasses perched on the end of her nose. ‘The neighbours’ll be talking about me already anyway.’ And the way she flicked a wary glance up and down the avenue of trailers gave me the distinct impression that the name of Christie McGraw came up a lot whenever couples in Hope Falls argued.

I took a seat in her living area and a few moments later she placed a pot of lemon tea I hadn’t asked for in front of me. It was accompanied by a china cup which may once have been beautiful, but which was now scarred by glazing which had become tessellated over many years of use.

‘I didn’t run off with the money, if that’s what you’ve come to ask me,’ she said in an acerbic Bette Davis drawl, but to be honest, that much was obvious just from looking around me. The foiling on the particleboard worktops was slowly peeling off; the throw on the sofa couldn’t quite cover the worn fabric on the seat and arms, and the pattern on the linoleum in the kitchen had faded through wear in two spots. The air freshener that had clearly been liberally applied in anticipation of my arrival could not fully mask the musky aroma of long-term water penetration.

She obviously noticed the look on my face. ‘What? You’re surprised to see me living like this?’

Her voice sounded like the movies of my childhood: rich and deep, with the smokiness of a good scotch. She dripped it over you teasingly, and I loved it.

‘Well, it’s just that… Erik was a wealthy man… And you were together for so long…’

She let go a dismissive snort. ‘Yeah, well, every love story becomes a tragedy if you wait long enough. Welcome to mine.’

I’d managed to get a commission to write a biography of Von Holunder to mark the centenary of his birth, and, after months of getting nowhere, I’d finally got Christie to agree to meet with me on condition that I flew out to New York. She hadn’t spoken to anyone in the media or the art world for nearly thirty years, not since a brief period of detention for selling a controlled substance. This fact helped me to convince my reluctant publisher to pay for a brief trip on the grounds that the cost could probably be recouped by syndicating the interview. At the same time, he had left me in no doubt as to the consequences for the company – and therefore me – if I failed to deliver a syndicate-able interview. Given the parlous state of my own post-divorce finances, this was not the start that I’d hoped for and I took to fawning over her in a desperate attempt to turn things around.

‘Well, I guess I’m interested in the love story, Ms McGraw. In the incredible relationship you clearly had with Erik,’ I said, ‘and how that inspired him.’

This was meant to be an acknowledgement of her status in the creative process, but Christie looked unconvinced. In all honesty, she appeared unconvinced by most things. Her face seemed to adopt a pose of wry scepticism by default. It was one of the things that had given the paintings such life.

‘In my experience he was absolutely the best lover a woman could ever have… Although, obviously, I can’t talk for Mimi,’ she added, raising her perfectly plucked eyebrow into a sardonic arch.

I blushed at her forthrightness. Christie still wore her sexuality like a ribbon. In the seventies and eighties Erik had portrayed her as symbolising the kind of sexual charisma that men found difficult to resist, but also impossible to control. And the row of Jane Fonda exercise videos bore testimony to the fact that she clearly still took great efforts over her appearance. If she had to fight, then this was her weapon of choice. Mimi had never stood a chance.

I didn’t know how to respond, and felt the pause between us lengthening. Eventually she decided to put me out of my misery.

‘So, you’re from London, Mr Viejo?’

‘Gabriel, please. Or Gabe. And yes, I’m from London.’

Her brow furrowed as she examined me. ‘You don’t sound like you’re from London.’

‘Well, I lived in Buenos Aires until I was twelve. They teach American English at the international school, and I guess my vowels are still stranded somewhere in the mid-Atlantic.’

‘Buenos Aires? I wondered about that. So I guess you’re related to Joaquín Viejo?’

I got asked this a lot when I met with people from the art world and I wasn’t embarrassed to answer. I was proud of my heritage. ‘Yes, he was my grandad.’

‘I thought so. I knew old Jo – I knew all the dealers back then. He had a big house just by the Parque Las Heras, didn’t he? And that beautiful place on Lake Morenito. We spent a weekend there once, me and Erik, on our way back from the Biennale.’

This didn’t surprise me. Most people in the art world of the seventies and eighties at least knew of Grandpa Jo. He was a big dealer back then – one of the biggest outside of London, Paris and New York – and he loved to entertain.

‘He was quite a…character, wasn’t he?’ she said.

I couldn’t tell what she meant by this, but the look in her eye suggested that it was not a straightforward compliment.

We carried on talking for a while; about how she’d met Erik, and how she’d ended up posing for him. I was trying to get a sense of the man behind all the bluster and braggadocio, and of the extent to which she’d contributed to the extraordinarily charged images of which she was the subject. But nothing seemed to flow. She seemed bored by my questions, and I was certainly bored by her answers. Looking back at my notes now, I can see that they’re a combination of quotes I could have pulled off the internet and idle tittle tattle about people on the art scene thirty or forty years ago. It was as though she was holding something back while she judged me. I didn’t like it, and found that, to my surprise, it really mattered to me whether she liked me or not.

It occurred to me that perhaps what was annoying her was my attempt to establish myself as the world’s foremost authority on Erik von Holunder. From her perspective, I guessed that must have seemed like a ridiculous presumption. She was, after all, his mistress for twelve years. I thought it might be worth my acknowledging this.

‘Look,’ I said, taking a sip of my lemon tea and fidgeting nervously with the cup, ‘I know this might sound like a stupid question—’

‘There’s no such thing as a stupid question, honey,’ she interjected. ‘Only stupid people. Go ahead. Ask whatever you want. I promise you I won’t think it’s the question that’s stupid.’ And she smiled a smile that didn’t even manage to convince her own face it was sincere.

I decided to confront her reticence full-on. ‘Have I done something to offend you, Ms McGraw?’

‘Erik always shaved when he was with me,’ she said, finally getting tired of my obtuseness. ‘Even when he was in his studio, working – especially when he was working. It was a point of professional pride.’

I hadn’t shaved – I mean, nobody under forty does now, right? – but it immediately became obvious that I should have. Christie set high standards for herself, and she had a commensurately low tolerance for those who didn’t set them for themselves. I could see that she took my stubble as a personal discourtesy. I closed my notebook and placed it carefully on her coffee table.

‘Ms McGraw, I owe you an apology. I want you to know that I appreciate that now. Can we push the reset button?’

She smiled a forgiving smile. ‘Indeed we can. Come back tomorrow – when you’ve had time for a shave,’ she said. ‘And a tie would be nice. A man should never wear an open-neck shirt after 11am unless he’s a lumberjack or holidaying in the south of France, and you, young man, are neither.’

I retired to a local coffee house to lick my wounds. As if I wasn’t feeling bad enough, no sooner had I sat down than a text came through from Suzy. It was the usual thing she had taken to sending me giving me one last chance to do the right thing. One last chance. She’d been giving me one last chance for the past two years and I had determinedly avoided taking any of them. The financial settlement had been signed off by a judge and the decree absolute issued six months previously, so it seemed a bit late to be trying to renegotiate things now. And besides, I’d given her fifty per cent of the house and my other English assets – which was, as I had repeatedly pointed out, the right thing to do. I certainly wasn’t going to be giving her a share of Grandpa Jo’s stuff as well. It was nothing to do with her and besides, I needed it to help me to get back on my feet after the ruination of my divorce.

I deleted the text without responding and tried to forget about it.

I’ve thought a lot about that decision since, but even now, I don’t know what else I could have done.

TWO

I didn’t expect to see Christie until the following afternoon, but a couple of hours later I got a call on my mobile asking me if I would care to take her out for the evening. ‘And don’t bother to turn up if you’ve not had a shave,’ she’d added. Something about the way that she said it suggested that she was both setting me a test and helpfully providing me with the answer, just to make sure that I passed. I didn’t understand the significance of that at the time and took the mere fact that she’d asked me as a compliment. Looking back, it seems unbelievably arrogant now, but at the time I just assumed that she was lonely and was genuinely interested in spending time in my company.

For my part, I was stuck in a hotel room miles from home with nothing to do, so the chance to spend an evening picking her brains about Erik at my publisher’s expense felt like too good an opportunity to miss. At the very least it felt like it was worth having a shave for.

And what a difference it made. The walls of suspicion which I had marched around so frustratingly that afternoon were removed the moment she opened the door and saw my clean-shaven face (and the bunch of flowers I’d brought with me).

It was difficult to tell if Christie had a nose for a good party or whether she attracted action by some kind of inner magnetic force. All I know is she came alive that night – and it was glorious. We left her trailer at 7pm for what I thought would be a quiet evening at the local diner discussing her life with Erik, and six hours later I found myself in a back-street bar downtown wearing a standard issue NYPD police hat, and salsa-dancing on top of a table with Christie and a Latvian acupuncturist called Liga from Riga.

I’d started off being slightly frustrated by Liga’s presence, but it soon became clear that she and Christie worked as a team, and I was the chosen audience for their entertainment. I suspected Liga had been chosen as Christie’s social partner because she met her exacting standards for personal glamour without quite overshadowing Christie herself. I also began to suspect that Christie was trying to hook me up with her pal. Certainly, when Liga disappeared briefly to powder her nose Christie wasted no time in asking me whether I might be interested. Liga, whose sharp-cut blonde bob set off a wide and innocent face, was undoubtedly an attractive young woman. She’d assured me that she could help people give up smoking, but after an evening of gyrating on tabletops in between her and Christie, interspersed with listening to them talking about the various men they’d dated, frankly I was just about ready to start again. So, in response to Christie’s question, I muttered something about the brevity of my stay and not really having the time to mix my business with pleasure. Christie was not impressed.

‘Oh puh-lease!’ she said, rolling her eyes. (Christie was a woman born for italics – and whenever she became animated it felt like the eyeroll had been invented just for her too.) ‘I’d slap you in the face and tell you to act like a man if I didn’t think it would turn you on!’

It seemed like a minor provocation designed to sow a seed in my mind; inviting me to probe her interest further. Yet no sooner had she said it than Liga returned, and the conversation moved on.

Utterances like that were Christie’s hallmark. There was something both alluring and yet disorienting about them so that, despite all the carousing on the tabletops, the thing that struck me most was not how much fun Christie was, but how beguiling. She drew you in, but at the same time kept you out. It felt like a talent.

And I was clearly not alone in my admiration of her: throughout the night there were plenty of guys attempting to start up conversation or join our little trio, and when Christie got up to go to the bathroom her path was marked by a line of turning heads. I don’t imagine anyone knew who she was or what she’d been, but you could tell from their looks that they all wished they did.

Liga must have noticed my eyes following Christie across the room because she interrupted my reverie with a question, asked in a tone which hinted at some disappointment with me.

‘You like Christie, don’t you?’

I got the impression that she was used to asking this question, and was used to being disappointed by the answer, so I wanted to remain non-committal in order to preserve the dignity of both parties.

‘I think she’s a fascinating woman. And what a story she has to tell.’

‘That’s good – that you think she’s fascinating. She is. That’s what I admire about her: she can make men be fascinated by her. I wish I could.’

‘Oh, of course you can,’ I said in a way that was meant to sound encouraging but which I immediately worried sounded like I was hitting on her. She didn’t seem to take it that way though.

‘Not like her. She can make men pay attention to her, but on her own terms. She doesn’t give in to them, because she knows what’ll happen if she does. I’m really bad at that. I try to be like Christie, but I worry too much that they’ll lose interest.’

I suspect that my face betrayed my confusion at what she’d said because she then took a swig of her margarita and spoke to me as though explaining something to a small child.

‘Men get their power by having sex; women get their power by not having sex. And Christie’s not had sex with more men than any woman I know.’

I didn’t know quite what to say, but I could sense what she meant. Christie didn’t discourage anyone’s attentions, but neither did she encourage them. Or, to put it another way, her ability to attract men seemed predicated on an equal but opposite ability to hold them at bay.

Perhaps sensing my discomfort, Liga decided to change the subject.

‘So, you’re divorced.’

I started. ‘How did you know?’

Liga smirked. ‘Your ring finger. There’s a pale stripe on it. I guess there was a ring there once.’

I blushed. ‘Yes. There was.’

My divorce was not the only failure of my life, but it was the most public, and it still felt raw. I had somehow come to believe that just by looking at me everyone could see that I was divorced – an insane idea that Liga had just reinforced.

‘What went wrong?’ she asked, avoiding eye contact and playing with her drink.

I wasn’t used to people being so direct. In Britain they tended to skirt around the issue. This tendency was exacerbated in my case by the fact that everyone who knew me knew exactly what had gone wrong and thought it so obvious that it would be rude of them to keep pointing it out to me.

‘I come from a family that some people would regard as fairly wealthy – which, just to be clear, doesn’t mean that I’m wealthy. I’m not. Not at all. And certainly not now. Anyway, my wife had a…she came from a very different background. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. It’s just that… When we met…I think she had a certain impression of what life with someone like me might be like, and I think the reality was a disappointment to her.’

Liga looked up at me with curiosity. ‘The reality?’

‘It’s not all holidays on the Côte d’Azur and servants to tidy up after you. We both still had to work. I still had to worry about the mortgage. It was probably pretty similar to the life she’d left behind, and I think she was expecting it to be different.’

‘So you think she was a gold digger?’

I paused for a moment. This was one open goal I felt it would be unwise for me to score into too enthusiastically. I decided to demur lest I appear ungentlemanly.

‘Other people – people who knew us as a couple – they’ve suggested that to me. Friends warned me about it before we got married. But I hope there was more to it than that. Honestly, I don’t think she was a bad person.’ I tried to convince myself as I spoke those words that this observation was true about twenty-five per cent of the time. ‘I think she genuinely convinced herself that she loved me – at least at the beginning. She just expected me to make her life something that I couldn’t make it. Or rather, I think she expected people to treat her differently, and got frustrated with me when they didn’t.’

I’d travelled three-and-a-half thousand miles in the hope that for a few brief days I might escape the constant reminders of my ignominy, but here I was talking to a young woman whom Christie had clearly only invited along as a potential romantic interest for me, and even she only seemed interested in my divorce.

I looked up, hoping that Christie might reappear and rescue me, and was relieved to see her returning from the bathroom. As she sauntered back to our table, I caught sight of one of the patrons being told in no uncertain terms by his female companion to avert his gaze.

‘If you look over your left shoulder there’s a guy being told off for looking at you by a woman young enough to be your daughter,’ I joked as she resumed her seat. I thought she would take some pride in this, but it seemed to bore her.

‘I don’t look, honey. Ever. I’m looked at.’

It sounded ridiculous even as she said it – the kind of self-aggrandising narcissism that I found so annoying in Gen Z’ers and certainly didn’t expect from a sexagenarian (even one as prone to self-dramatising as Christie). And yet I found myself being pulled into a subtly different orbit. No longer were my thoughts centred on my regrets about Suzy or my hopes for my biography of Von Holunder, but on this extraordinary woman who seemed to stand in wilful defiance of all that society said she could be.

Perhaps it was this ability to shape the universe around her – to organise other people in relation to her by means of her own personal gravitational force – that made me feel as though I was being admitted to a very select club. Whatever it was, it was one of Christie’s more unsettling traits that she somehow managed to get you to tell her more than you knew you should. I was supposed to be interviewing her, but by 2am I had still not managed to glean any useful information for my book, while, as the alcohol began to take hold, I found myself verbalising thoughts about my marriage and divorce that I’d never articulated explicitly before, even to myself.

‘It was never really an equal partnership – financially, socially, even intellectually. Because of my grandfather, I had a lot of contacts that were quite useful to Suzy. I’d got access to a couple of holiday homes that were in the family too. And I like to think that my name has a certain amount of intellectual heft in the art world. Suzy wanted to leverage all of that, but she didn’t have anything she could offer in return. Except her beauty, and that…well, that’s not really the same thing.’

‘So you think she was a gold digger?’ Christie asked.

‘That’s what I said!’ Liga interjected. ‘But apparently it’s not that simple.’

‘I opened lots of doors for her,’ I said, ‘but, for whatever reason, she never quite managed to walk through them. She never felt she belonged. And she came to blame me for that, I think.’

‘But why?’ asked Christie. ‘I mean, you did your bit.’

‘I like to think so – although obviously, you can’t help wondering if you could have done more – given how things worked out. But there’s no doubt that, by the end, I came to feel guilty about my relative success – however modest it was in reality – and I came to feel responsible for her sense of failure. And she came to resent me for the first of those things and blame me for the second.’

‘Jesus, honey,’ Christie said when I’d finally run out of steam, ‘it sure doesn’t sound like your relationship was much fun.’ And she gazed at me sympathetically.

‘I don’t really think of it as a relationship,’ I replied. ‘More a kind of character-building experience.’

Something about her look changed. It became deeper, as though examining me. I’d noticed this look in the paintings. There it was arresting, but in person, when she was directing it at you individually, it felt strangely intoxicating.

‘Is that why you’re doing this? This book?’ she asked.

The question took me by surprise.

‘I don’t understand. I admire Erik and want to bring his legacy to a new generation.’

‘But you also need to get your mojo back – put your marriage behind you.’

I shuffled uncomfortably. ‘Look, this is a great gig for me. I don’t deny it. But that’s not what this is about. There’ll be lots of interest in the centenary. I want to capitalise on that. Mimi’s trying to organise a retrospective.’

She gave me a wry look. ‘Really? Even now?’

‘I know Erik’s been out of fashion for a while, but we’re hoping it might lead to a reappraisal.’

I saw her bridle. ‘“We”? So did Mimi send you?’

‘No!’ I protested. ‘My publisher sent me.’

‘But you have spoken to Mimi?’

I considered this issue for a moment before deciding that it was best not to lie. ‘Of course. She was his wife, and she’s always been happy to talk about Erik to anyone who’ll listen. It’s an authorised biography because she’s authorising it.’

Christie gave a dismissive snort. ‘And no doubt she painted him as a saint who was led astray by this dreadful scarlet woman.’

‘Not at all.’ This was true, although only because Mimi had not once mentioned Christie during our nine hours of interviews. In Mimi’s narrative, which she had already set out at length in her 1992 memoir of life with Erik, Von Holunder was simply a great and glorious artist who had been cruelly marginalised by an art world establishment that had inexplicably had its head turned by the twin attractions of novelty and mediocrity. (Like dogs and their owners, I find that the subjects of biographies invariably come to resemble their authors.) This was clearly the narrative that she anticipated my more considered volume would also take, even though it was far from being the whole story. Yet it occurred to me that I could use the antipathy between the two women to my advantage.

‘Yes, she’s given me the official version of Erik. What I want is your version. After all these years of silence, I think that’s what’s going to sell my book.’ For the first time I consciously met her stare. ‘I want to tell your story.’

‘That’s great. But are you sure you’re ready to hear it?’

‘Of course.’

‘Because my story is filled with broken promises, terrible choices and ugly truths.’ She leant forward. ‘But I guess that’s what makes it interesting.’

And with that she had me hooked.

THREE

I woke about eleven. After a night of bar light and indiscretion, the sun felt searing on my eyes. My mind was filled with a dull fog and my stomach was struggling to contain the roiling sea of Tequila slammers inside. I took some aspirin and shaved – again – but couldn’t yet face the day, so returned to my bed and doom-scrolled on my phone.

Back in England, I could see that the news websites were fixated with the story of an unravelling corruption scandal that was currently playing out in the courts. The primary figure implicated in this was the Greek business tycoon, Constantine Gerou. I vaguely knew Conny because, apart from Mimi, he held probably the largest private collection of Von Holunders in the world, so I’d been in touch with his office when I’d put together Erik’s catalogue raisonné, and he contacted me sometimes if he wanted someone to vouch for a painting he was being offered. We’d met a couple of times, although I’d mainly dealt with his entourage.

Anyway, it seemed that Conny had recently left Greece rather abruptly after a series of his associates were arrested. The assumption was that he was trying to get to his American home, but in the event he had got no further than London before the Greek government requested his extradition – a request to which the British authorities were legally obliged to accede. But Gerou was not unduly keen to return to his homeland and, accordingly, was currently holed up in one of London’s most exclusive hotels while his appeal played out in the courts. It occurred to me, reading the coverage of the trial, that while Conny made great play of the fact that he was a self-made man whose fortune came solely from his business, he had always been studiously vague about what his business actually was. There had been some suggestions that he ran an import/export company, but exactly what he was importing and exporting had never been made clear. The Greek government now seemed to be suggesting it had found out and was not impressed.

I smiled to myself and moved on in the naïve belief that the story was simply about a grifter getting his comeuppance and had nothing to do with me.

By 3pm I still felt dreadful and imagined that Christie would too. Yet when I eventually turned up at her trailer (sporting the tie I’d managed to pick up at JC Penney’s on the way) she was sipping grapefruit juice and looked as fresh and lively as a new-born lamb.

‘Now, don’t you look smart?’ she said, as though I was an eleven-year-old on my first day at secondary school. ‘You look tired, though – did you not sleep well?’

To my shame, I couldn’t bring myself to admit that I’d been outdrunk by a woman old enough to be my mother, so I mumbled something about the hotel beds being uncomfortable.

‘Well anyway, come in, young man. I’ve got something to show you,’ she said. ‘I hope you’ll like it,’ she added, with just a hint of nervousness.

At the point at which she grabbed my hand and pulled me into her living quarters, the spectrum of possibilities of what she was about to show me ranged, in my mind, from a homemade blueberry pie to the severed head of Liga from Riga. After seeing Christie in full flow the night before, almost anything between those two extremes would not have caused me to bat an eyelid.

But nothing could have prepared me for what I did see. For there in front of me, propped up against the easy chair that I had been sitting in not twenty-four hours previously, was a five-foot by four-foot oil painting featuring a naked woman bathing in her garden.

I had spent more time than was probably healthy over the previous decade-and-a-half looking at the couple of hundred or so authenticated paintings of Erik von Holunder, and I could see instantly that it bore all the hallmarks of his work. The style, the colour palette, the framing of the scene were all classic examples of late-period Von Holunder. In all those hours of searching through private collections, exhibition catalogues and the archives of some of Europe and America’s finest museums, however, I had never seen this painting before. Yet here it was, in a down-at-heel residential trailer park; its glory a secret Christie was sharing only with me.

But what a glory it was.

‘He called it Susanna & the Elders – like the Rembrandt,’ she explained.

I stared at the painting in front of me with a mixture of stunned awe and an excitement I could barely contain. I knew that towards the end of his life Von Holunder had painted a series of eleven reinterpretations of works by the Old Masters. He’d never been entirely happy with them, and most had been dismissed by the critics (including me) as derivative and uninspiring. But what Christie showed me that afternoon was extraordinary. It was a representation of a scene from the biblical Apocrypha, most famously painted by Rembrandt, where the young Susanna is caught bathing in her garden by two lecherous old men. For the most part it was an unremarkable re-imagining of a story that was perhaps over-familiar to students of art. But there, at the heart of the canvas, was Christie – and her presence transformed everything.

Whereas it was traditional for Susanna to be shown as virginal and pure – caught unawares with no idea what she should do – Christie’s Susanna knew exactly what she was doing. Her face suggested that, far from feeling terrified and powerless, it was the unsuspecting elders who were caught in her trap. Blinded by their lust, they didn’t seem to realise that the object of their desires was more worldly-wise than they supposed and had anticipated the weaknesses of men and prepared, somewhat ruefully, for them. Her expectations had been proved right, but she took no pleasure in that. In fact, it seemed to fill her with a strange combination of Machiavellian determination and sorrow.

It was, in short, a Susanna unlike any I had ever seen. Vignon, Badalocchio, Von Hagelstein, even Reubens and Tintoretto – none of them had captured anything as interesting, as transformative, as the look on Christie’s face in that picture. Von Holunder had taken the tired and familiar trope of the passive, victimised woman, and turned it on its head. This was a powerful woman given agency and emotional depth, while the men were rendered impotent by their desires.

I wanted to tell Christie all this, but my mind was racing so far ahead of my mouth I could barely construct a coherent sentence.

‘Christie… What…? How…? I mean…this is incredible!’ was as much as I could say.

‘I know,’ she replied, without raising either her voice, or her eyelids.

‘But…where – I mean, why haven’t we seen this before? Why did Erik not include this in the show? This is better than any of the others. Hell, it’s better than anything else he ever produced!’

‘That’s what I told him. Apparently, he didn’t think it did justice to my bo-sooms! Difficult to argue with him on that point,’ Christie said, with a hint of pride. ‘But I guess there’s only so much you can do with a paintbrush.’

At that point I remembered something I’d come across in some of Von Holunder’s obituaries. There was rumoured to be a twelfth painting in the Old Masters series that had never been put on display. In one version of the story, Von Holunder had been so disappointed by it that he’d thrown it out. In another, though – the version that Mimi had mentioned in her book – Von Holunder had liked it so much that he’d kept it for himself, until he’d fallen out with Christie a few months before his death and the painting had been mysteriously lost. Mimi’s version had largely been dismissed for lack of supporting evidence but had found some currency among Von Holunder aficionados on the internet. Yet as I stared in wonder at the painting before me, I felt immediately, with a certainty greater than anything I had ever felt in my career, that this was that work. This was Von Holunder’s great, undiscovered masterpiece; the work that his other paintings had hinted he was capable of, but which we had never before seen him produce. I had studied him for years, yet until now he had always remained an enigma. This single work, however, seemed to unlock something in his psyche that meant my subject no longer felt impenetrable.

‘Thank you! Thank you for letting me see this. It changes everything.’ I was conscious of starting to sound like a gushing schoolboy, but there was something else I wanted to tell her; something I sensed she needed to hear. ‘I mean, I know Mimi said some horrible things about you in her book, but this will change how people see your relationship with Erik – it will change the whole story… He loved you, Christie. Even after all this time looking at his paintings, I couldn’t quite be sure – you hear so many things. But this…this nails it. The way he’s painted you there.’ I turned again to look at the painting. ‘The way he’s worked the paint for your figure – it’s different: more tender, more compassionate than anywhere else on the canvas. He’s trying to convey something to you there that maybe he couldn’t tell you to your face. He loved you, and nobody could look at this painting and not believe that.’

And then something remarkable happened. The veneer of the hard-boiled, sassy American fell away before me, and her eyes glassed with the suggestion of tears.

‘Thank you,’ she said with genuine tenderness. It was the first thing she said that I’d really believed; the first thing that didn’t feel like an act. ‘Hearing you say that…well, it helps me to believe that I’m not mad for seeing it too. I’ve tried to hold onto that for so long, but on the bad days I tell myself that I’ve been imagining it all these years.’ And for the briefest of moments she didn’t seem quite so self-possessed.

It didn’t last for long.

‘So. Do you think you could help me sell it?’

This was not what I had been expecting. ‘What? Why?’

‘I’ve done my research, young man. You know more about Erik than anyone else. And you obviously care about his work.’

‘No, not “why me?” I mean, why do you want to sell it? You’ve kept it over thirty years, right? Why now?’

Something about her face changed. It broke, there’s no other word for it, and for the first time she looked every one of her sixty-seven years. ‘Look around you, kid.’

I looked around. There was a lot of love and a lot of pride in that trailer – everything was clean and there was not a speck of dust anywhere – but that couldn’t hide what it was. It was clear that nothing had been replaced since the turn of the millennium. The photos on the walls, the knick-knacks on the sideboard, even the crockery on display in a chipped mahogany cabinet – they all hinted at a great and glorious past, but there was no getting away from the fact that this was a museum to a life that was now just a memory.

I didn’t know what to say. Sensing my discomfort, Christie decided to pile on more.

‘And you know what the worst of it is? I can’t even make the rent on this.’

It was the first admission of any kind of vulnerability that she’d made, and I took it as a gift. But getting me to sell Susanna & the Elders on her behalf didn’t seem like a sensible strategy.

‘Look, Christie. We’re paying you for this interview. I can phone my editor up to see if we can get payment through a bit quicker – just to help tide you over. And I’m sure when the book comes out it’ll reignite a lot of interest and bring in some more offers of—’

‘Oh, that’s not the worst of it. Honestly, if it was just the rent, I could figure something out. I’ve done it plenty of times before. I’m an attractive woman, Mr Viejo. I’ve never had a problem with suitors. There are always people keen to help,’ and I could see, even as she said it, that there was not a flicker of doubt in her mind that it was true, even then. ‘But things are a lot tougher now… I’ve got bigger problems.’

She slumped down into the sofa, crumpling in on herself like a collapsing soufflé. I couldn’t think of anything worse than the prospect of losing your home, even one as ostensibly undesirable as this, but Christie soon disabused me of that.

‘I have cancer,’ she said, trying to regain her poise. ‘There, I’ve said it. I’m at stage 2. Actually, I’m at stage 2B, if you want to be precise, although I’m not sure what the difference is.’

Her news dragged a silence out of the room which threatened to smother me until I felt compelled to break it. ‘Oh, God. I’m sorry… I’m so sorry.’ I didn’t know what else to say.

‘Don’t be; it’s not your fault. Even at 2B it’s still treatable. This doesn’t have to be the end. But I don’t have insurance, and we don’t have your socialist healthcare system over here, so I need money – lots of it. And I need it now. Once we get to stage 3 my prospects look a lot less rosy.’

I had laboured under the delusion that Christie’s emergence from her self-imposed silence had been something to do with me; that she’d read my admiring comparison of Von Holunder with Freud in the spring edition of World Art, or perhaps even my monograph on his change of style from 1975 onwards, and decided that I was the person she could finally trust to tell her side of the story. But, like most things to do with Christie, it seemed I was naïve. I’d just been lucky enough to write to her requesting an interview at precisely the point she was most desperate for cash.

‘So, what d’ya say? Are you gonna help me sell it?’

I sucked in a long breath and played for time by asking for a coffee while I gingerly began to piece my thoughts together. Slowly, an appropriate response began to form in my mind.

‘Look, this is a fabulous opportunity and I’m obviously very flattered. But I’m not a dealer. I’m a critic. This is not what I do.’

It was a response that I had carefully calibrated in my mind to avoid causing any offence, but also to try and draw a line under the issue politely. However, subtle English social signalling was not something that Christie seemed to pick up on.

‘I know, but I kinda figured you could help me out. For Erik.’ Then she looked at me with her big blue eyes and I felt a little tug at my heart.

‘I would love to. But I feel I’ve got to be honest with you here. Erik’s work can be tough to sell at the moment. You don’t need me: you need an experienced dealer.’

‘Yeah, but I don’t know who to go to. Most of the people Erik and I used to hang around with are dead now. Or at least, they’re not taking my calls. I can’t get anyone to speak to me. Not anyone who counts.’

‘Look, I know someone who works for Marian Goodman. She specialises in contemporary European art for the American market. I’m pretty certain that Erik gave her some stuff to sell when she first opened in ’77. I’m sure my friend would be happy to take a look at this for you. I can put you in touch.’

‘Is she under forty?’

‘Marian? God, no. She’s even older than you!’

‘Imagine!’ she said, in mock surprise. ‘No, I meant your friend.’ My chastened silence indicated to Christie that she was. ‘Because to be honest with you, if she is, I’m not sure that she’ll take my call. No one under forty seems to have even heard of me.’ And everything in her weak attempt to muster a smile told me that she had been brutally exposed to the bitter truth of that fact.

It seemed a genuine travesty. Even with the market’s rather sniffy recent valuations of Erik’s work, a decent Von Holunder could still reach $400,000. Without You I’m Nothing had even sold for $500,000 in New York just three or four years previously – still well below the prices that Erik’s work was fetching in the late seventies and early eighties, but certainly not to be sniffed at. Yet the woman who had been their subject was stuck in a shitty trailer, penniless, and facing cancer alone. In a world of unfairness, I knew that this was hardly the unfairest thing of all, but it suddenly felt deeply unfair in a way that I’d never noticed before. And it was one unfairness I could actually do something about.

I fixed Christie with a firm stare. ‘She’ll take your call for this. I promise you.’

‘Really?’ She sounded like she couldn’t quite believe it. ‘I mean, a picture of a naked woman – it’s not exactly the zeitgeist right now.’

I grew animated. ‘But this is different. It’s a naked woman who’s in control, who’s fighting back. It’s a naked woman who won’t put up with it all any more, who’s changing the narrative. That captures the zeitgeist perfectly.’

‘Hashtag – MeToo,’ said Christie, sarcastically. She fought with all her might with the weapons at her disposal and clearly had no truck with those who wanted to fight another way. It was the one thing that disappointed me about her even then, and I made the mistake of telling her so.

‘Oh, don’t tell me you’re a feminist,’ she replied. It seemed to disappoint her in a way that suggested some question of my manhood was at stake.

‘How is that a bad thing?’

‘Let me tell you something, honey: the guys who call themselves feminists are always the first to put their hand on your ass.’

I could tell immediately from her weary timbre that this was more than just a wisecrack. Something in me wondered for a moment if it wasn’t also a warning, but her voice seemed too pregnant with regret for the comment to be aimed directly at me. She was holding on to a disappointment that I decided it was best not to probe.

However, I wanted her to appreciate the potential significance of what she had shown me. I looked her straight in the eye to try and ram the point home.

‘Look, you’ve got something very valuable here, Christie. This is a major work by a significant twentieth-century artist that has never come on the market before. And it has an impeccable provenance.’

Christie’s face adopted a demure look, and she glanced at me out of the corner of her eyes. ‘Well… I wouldn’t say “impeccable”.’

I raised a quizzical eyebrow as a frisson of concern shivered down my back. ‘You wouldn’t?’

‘No, I definitely couldn’t say that.’ She leant forward and put her hand gently on my knee. ‘That’s kinda why I need you…’

She opened up her deep blue eyes imploringly and invited me to wallow in their oceans.

I used to think I fell in love with Christie, but looking back I wonder if I didn’t just fall in love with the idea of Christie. Whichever it was, I do know that it happened in that moment.

And that it was the worst mistake of my life.

FOUR