Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Krimi

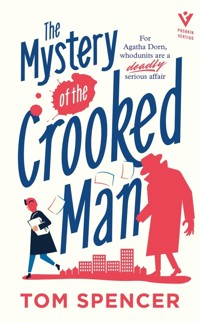

- Serie: The Agatha Dorn Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

Meet Agatha Dorn, cantankerous archivist, grammar pedant, gin afficionado and murder mystery addict. When she discovers a lost manuscript by Gladden Green, the Empress of Golden Age detective fiction, Agatha's life takes an unexpected twist. She becomes an overnight sensation, basking in the limelight of literary stardom.But Agatha's newfound fame takes a nosedive when the 'rediscovered' novel is exposed as a hoax. And when her ex-lover turns up dead, with a scrap of the manuscript by her side, Agatha suspects foul play.Cancelled, ostracised and severely ticked off, Agatha turns detective to uncover the sinister truth that connects the murder and the fraudulent manuscript. But can she stay sober long enough to catch the murderer, or will Agatha become a whodunit herself?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise

‘With a prickly protagonist and a plot that’s twistier than a bag full of corkscrews, this one will keep you guessing until the end’

FIONA LEITCH, AUTHOR OF A CORNISH SEASIDE MURDER

‘As fresh and pithy as a ripe tangerine—a hoot from start to finish. Tom Spencer has created a riotously funny crime caper that Agatha Christie would have loved’

M.H. ECCLESTON, AUTHOR OF THE TRUST

5

To Elizabeth, Alistair and Linus

6

CONTENTS

PART ONE8

1

The call is coming from inside the house. As per bally usual.

The guttural voice promising to sever my thus-and-such and rip off my what-have-you. And, as always, describing the scene in minute detail—the white tiles on the kitchen wall with the scarlet trim. My disastrous brown dress with the puff sleeves and the smocking at the neck.

I’m here. You can’t see me, but I’m here. I’m in the room.

It is 1980. Being eight years old, I am not at all sanguine about the whole thing; not like nowadays. There are no mobiles, no caller display. I need help, but no one is here. Heri, my brother, is in his room, nursing his wounds from his most recent playground beating. He is the kind of child who elects to go by the German ‘Heribert’ when his given name is ‘Herbert’, so you can see why he gets bullied. My mother Clara is off plundering one of the various bottles stashed around the house about which she thinks we do not know. When she finally hears my howls and arrives in the kitchen, I sob that the murderer must be phoning from right here, from the next room. She harrumphs and tells me there is no way to call your own phone number. (Which is true. I don’t know how the killer is supposed to have managed it in those seventies horror films.) She takes the phone from me and holds it to her ear. As always, nothing, only the dial tone. I am entirely hysterical, but Clara has dealt with my nonsense too many times. ‘Why must you always lie and lie?’ she yells. ‘Normal children do 10not lie and lie and lie!’ She cuffs me on the back of the head with the handset, which is hefty and made of hard plastic, and tells me she does not want to see me again until the morning. No dinner for Agatha again.

I’m right here with you.

I don’t have a name for the Crooked Man yet, but I am already becoming intimately familiar with his ways.

I was in my small office, the smallest one at the Neele Archive, thirty-seven years later. I was trying to placate a headache that had been coming on all morning, while waiting for Ian, my boss, to telephone with the good news. Agatha Dorn, Curator of Prose! That was what I was about to become.

What’s the Neele Archive? I hear you ask. And what’s a Curator of Prose, for that matter? Well, I suppose I shall educate you if I must. The Neele is like a fancy library in the heart of the City of London, housed in the remaining part of a row of terraced Georgian houses that the German bombs managed to miss during the Blitz. Only, where your ordinary library has large-print editions of romance novels, we have first editions, holograph manuscripts, and other rare items of scholarly interest. Where your ordinary library has old ladies checking out lurid thrillers, we have celebrated academics from around the world visiting our collections. And we don’t let them check out anything. They have to work in our reading rooms, under the beady eyes of our curators.

The curators! It has, you see, to be somebody’s job to look after the collections—to handle donations—to search out and purchase new items—to create coherent collections around which we can structure exhibitions and on which we can build 11our reputation. And that was what I was waiting to hear that I had become.

If I were to look over at the door, I would catch my reflection in the little window that looks out onto the Neele’s main hallway. When I’ve had a couple of gins-and-water, I like to think I resemble a taller, bonier Fiona Shaw. When I’m hideously sober, which I am now, I have a less flattering opinion of my appearance.

I hate the little window in my door; it lets any old hawker snoop on me in my own sanctum, which is frankly unconscionable. I tried taping paper over it when I first started working here, but Ian said the paper looked disreputable and made me take it down.

Next to the door is a hatstand, on which is arranged my usual drag—a big grey tweed greatcoat and a red hunting hat with ear flaps. I wear them winter or summer. Though climate change is making that less tenable these days.

Instead of looking at the window then, I tried looking at the back of the anglepoise lamp that cannot be restrained from swinging directly into the path from the door to the desk. The desk itself only fits because it is wedged so close to the wall that eking my way to my chair feels like getting into the middle seat on an aeroplane.

But looking at the lamp was making my head worse, so I closed my eyes. I get these headaches that start as a little dry sensation in my left eye. One can hardly tell if it is a headache or if one’s just dehydrated or something, but one has to get good at noticing the exact quality of the sensation. If one doesn’t start taking ibuprofen the very second one feels it, one is essentially finished. Today, I had missed the 12window. I hoped no one would look in, or they might think I was sleeping on the job, which would be unfortunate today of all days.

Vera, the bed-blocking former Curator, had retired six months previously, and I had been serving as what everyone assumed was a faute-de-mieux interim while we did a search. When I had asked Ian if my new position would be made permanent, he said that I was welcome to apply for it—meaning that there wasn’t a chance in hell. The Neele was where I had ended up when I dropped out of university, and I had spent the last twenty-five years being ignored, passed over, and generally made to feel like a waste of space.

But all that was about to change. I had called Ian’s bluff and applied. More than that, I had been a first-rate interim. I had always excelled in small, unnoticed ways. So, I simply ensured that people noticed. For example: I saw that the catalogue still had a subject heading, ‘Indians of North America’, and I altered it to ‘Native Americans’. Before, that would have been that: just me, muggins, silently making our place of work better, with no hope of reward. Now, I circulated an email assertively but compassionately chiding the staff for having let a racial slur stand in our catalogue, and noted that, incidentally, I had now taken the initiative to change it. I could just imagine them reading the email and respecting the heck out of me for it.

Now that they could see what a great colleague I was, the job was basically in the bag.

And yesterday, Bunner, the ovine granny who does accessions, and whom I pretend to like, had told me that Ian had told her he was going to announce it today.13

The phone rang. At last!

‘Miss Dorn,’ said a voice that was not Ian’s. ‘Are you the daughter of a Mrs Clara Dorn?’ Christ. Now? Now? I suppressed the urge to tell him it was none of his business. Instead I said that I was.

‘I am the manager of the Sunshine Garden Centre in Palmers Green. We have your mother here in the security office.’

‘Why is she in the security office?’

‘One of our loss-prevention operatives found her outside the premises with a bar of Kendal Mint Cake she had not paid for.’ I wondered how many loss-prevention operatives one garden centre needed. ‘Ordinarily we refer such matters directly to the authorities but your mother appearing to be a little—well, a little confused—not to mention, ah, the question of her advanced age, we chose to detain her on site until further arrangements could be made.’ He seemed to expect me to say something at this point, but I let an uncomfortable silence drag on instead.

‘We asked her if there was someone we could contact and she gave us a card that had your name on it,’ he said at last. Another pause. I think he thought I would have been speeding to rescue her at the first mention of the authorities. ‘Do you think you could—come and get her?’

God’s teeth! Where the h—was Murgatroyd?

There was nothing for it, though. What was one supposed to say? No, I’m too busy waiting to be promoted to come and bail my hateful mother out of garden-centre pokey? ‘I’ll be there as soon as I can,’ I said. It was more than she deserved.

Clara’s long-standing and harmlessly eccentric lapses—the occasional finding herself in Tesco without her skirt or 14serving the chicken without having cooked it and so forth—had recently been anointed dementia. When he had told me, Clara’s GP had seemed surprised that I did not immediately leap up, grab my things, and move back to my childhood bedroom in Palmers Green in order to wipe Clara’s bottom for her until she died. Instead, I was making do with a system where she gave a next-of-kin card to whomever came across her in difficulties. Murgatroyd was the top name on the list, but she had been falling down on the job. Murgatroyd’s being my—what? best friend? ex-girlfriend? Ugh, I don’t know, whatever she was—being that, Murgatroyd was admittedly not next of kin, or even kin at all. But she had been happy to do it, and I had not. At least, that was what I had thought.

I looked at my watch. It was just before ten. We had a staff meeting at one. Perhaps Ian was going to announce the promotion then. And if he wanted to reach me in the meantime, he could always ring my mobile. I could get Clara home, pray to God I could reach Murg, and get back in time for the meeting. I decided to go for it. It was not as if I had much of a choice, in any case.

Having extricated Clara from the garden centre and got her back to her house without too much trouble, I succeeded in raising Murgatroyd. It wasn’t hard. You just had to keep ringing over and over until she picked up. I made a mental note to put an addendum to that effect on Clara’s senility card. I told Murgatroyd she needed to come over.

When I got off the phone, Clara was standing over the stove, making an omelette, and at the same time, smoking a cigarette. She was wearing her nicotine-stained dressing gown and her 15slippers that looked like she had walked through a puddle of diarrhoea.

‘It’s good to see you again, Agatha,’ she said, without turning round.

‘Yes, you too, Clara.’

‘Agatha, I forget how you take your tea.’

I liked my tea poured directly down the sink, like all right-thinking people, but I didn’t want to start a fight. ‘Milk and two sugars,’ I said.

‘And how is your mother?’

‘She’s suffering a little bit at the moment.’

‘Aren’t we all? And you’re doing a degree, aren’t you? Something to do with libraries?’

‘That’s sort of right.’

‘And your mother’s paying for that, I suppose? That seems to be how it is nowadays, children just stay at university forever, don’t they? Well, it’s better than working.’ I said nothing. ‘It takes all sorts, doesn’t it? Everyone finds their little niche. Be it ever so humble.’ She turned and placed in front of me a perfectly cooked French omelette, larded with cigarette ash.

I heard the front door; Murgatroyd had arrived. I gratefully fled the kitchen.

Murgatroyd’s short, round body, wrapped in a swath of tie-dyed material that one supposed was a dress, ambled into the room. ‘Murgatroyd, what on earth are you playing at,’ I said. ‘You’re supposed to be first call! This is the third one I’ve had to do in two weeks!’

I expected Murgatroyd to be apologetic, or defensive, or angry, but instead she just seemed solemn and headed into the sitting room.16

‘Agatha, are you going to be strange if I try to talk to you about something serious?’ she said.

‘I can’t think what you mean,’ I said. ‘I shall be as appropriate as always.’

‘Well—’ Murg said. ‘Maybe you’d better sit down. That’s what people say in these situations, isn’t it?’

‘What situations?’ I said, remaining standing.

‘Look,’ she said, ‘when you phoned for the fourth time in a row, I was in the doctor’s waiting room. That’s why I didn’t answer.’

‘Thank you for picking up then,’ I said. ‘I kept ringing because it was important.’

‘Agh!’ said Murgatroyd. ‘I knew you’d be like this! Look! Whatever it is that makes you incapable of caring for your mother, you need to deal with it. Agatha, I don’t know how to tell you. I have cancer. That’s why I haven’t been available lately.’ I had a whole retort lined up, but, thanks to Murgatroyd’s irritating announcement, it would be in poor taste to say it now.

‘Is it bad?’ I said, like an idiot.

‘I’m afraid so. They think I have a few months. You’ll have to make other arrangements fairly fast.’ Her voice cracked a little bit, whether because she was laughing at her witticism or because she was starting to cry, I wasn’t sure.

‘Agatha,’ she said. ‘I need to tell you something else.’

‘Yes?’ I said. I was still cross about the cancer.

The irritation must have come through in my voice, because Murg made a face as if she had thought better of whatever she had been going to say. ‘Well, no,’ she said instead. ‘It’s not a good idea—yet. When I’m gone, look in the Secrets Book. It’s important. You know where to find it.’17

Honestly! Why she couldn’t just spit it out! In the old days, Murgatroyd used to make a great performance of writing in a purple journal made for tweenage girls, with SECRETS BOOK embossed on the front and a heart-shaped padlock. If I annoyed her, she would say ‘That’s going in the Secrets Book’ or ‘When they read the Secrets Book, they’ll see all the s—you put me through, Agatha Dorn.’ I never really knew what she wrote in there. But I knew she kept it in her bedside table.

‘OK,’ I said. I have never been good in this kind of situation. I hate it when people are ill or unhappy—it sort of spoils everything for me. I did nothing for a moment, then I awkwardly put my hand on top of Murgatroyd’s. She seemed to take this as a sign that I couldn’t find the right way to express the profound sympathy I was feeling, and gave me a disgusting, sentimental hug, sniffling as she did so. She had always cried easily. I hugged her stiffly in return for what I hoped was an appropriate amount of time. How did one tell? Then I gave her a release-me pat on the back and said I was sorry, I had to go back to work, I had a migraine coming on, which might or might not have been a lie, I couldn’t really tell. I would telephone her the next day with a plan about Clara, I said. That was definitely a lie. I had no idea what I was going to do. Then I speed-walked down the street to the bus stop to begin the trek back to the Neele.

2

I made it to the office with mere minutes to spare. On my way to the meeting room, I walked past Nancy’s office and glanced inside. Now I thought about it, it looked roughly the same size as mine, but somehow hers felt serene and uncluttered. Nancy waved at me and trotted towards the door so we could walk to the meeting together. I pretended not to have seen and sped up.

Did I tell you about Nancy? Nancy is twenty-four years old. Archive people are typically a motley crew, all weird hairlines and undiagnosed spectrum disorders, but Nancy has sharp eyes and bright little teeth. She is English, but she did her postgrad at Yale, as you do, where she got herself named co-director of her adviser’s extremely high-rolling project digitizing Emily Dickinson’s manuscripts. Just after she started, they had her on Radio 4, talking about Emily Dickinson. I tried to avoid listening, but the interview came on while I was in a taxi one day, causing me to have a panic attack. I had to tell the driver I was carsick and get out. It was like those T-shirts: My girlfriend went to Tenerife and all I got was this lousy T-shirt. Nancy had created ‘a landmark in public digital humanities’, and all I had was this lousy assistant curator’s job. Did I say I hated her?

The meeting started with no announcement about my new job, but I was cheered by the fact that Nancy immediately put her foot in it. We were talking about the summer exhibition, 19and she came out with something like ‘What if we showed the Poe material?’ There were two reasons why this was a stupid thing to have said. First, our unrivalled collection of early Edgar Allan Poe papers—purchased for a song by Woodward Neele III, on a trip to New York in the early 1840s, when Poe was still a nobody—they were kind of our thing. We had the holographs of ‘The Purloined Letter’ and ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’. Everybody knew it: we had shown them about ten trillion times. Nancy’s suggesting we display them for the summer exhibition was a bit like the new hire turning up at the Disney board meeting and saying, ‘Hey, I really think we might be able to make something of this “Mickey Mouse” character!’

Second: last time we did a Poe show, a few years back, Ian had tried to augment our collection by purchasing what was supposed to be a rare private pressing of The Raven. The Neele had ended up with a good deal of egg on its face. Not only had the chapbook turned out to be a fake, but it had been printed on paper whose watermark, on closer inspection, featured an image of Mr Poe doing something unspeakable to a grinning cartoon character. Ian valiantly suggested that Poe, who was after all something of a literary hoaxer, might have engineered the scandalous device himself. However, Bunner—of all people!—pointed out that the gentleman being violated in the image was an Internet meme known as Trollface, whose creation post-dated that of The Raven by more than a century and a half. In any case, the matter was settled a couple of days after the discovery when a masked ‘YouTuber’ named art-brute posted a video of himself wiping his bare posterior with a second copy of the fake chapbook before burning it, along with our exhibition 20catalogue. Attempts were made to identify him from the video, but all we could tell was that he was a tough-looking gentleman wearing a dog mask. I suppose it was meant to be funny, but we all just looked stupid. Even though the Sun published a still from the YouTube video with the headline ‘EDGAR ALLAN POO’, no one at the Neele was laughing.

But Nancy was sharper than I thought. It turned out she had a whole spiel about how, in this age of fake news, Poe was the troll-as-performance-artist way ahead of his time—didn’t he fool doctors all over Europe with his story about how a terminally ill patient had been kept alive with hypnosis? Didn’t crowds take to the streets in celebration when he wrote a story claiming that an aeronaut had crossed the Atlantic in a balloon? We could put it on display next to a selection of Flat-Earther tweets from this year. And so (she said) when you looked at it like that, even though Poe hadn’t himself made the obscene Raven chapbook, hadn’t it been created precisely in his spirit? We should show it again—show the video next to it—reclaim it—show it with pride!

There was a disturbing quantity of nodding around the table. I had to act fast. ‘Nancy dear,’ I announced, ‘I’m sure it’s a tremendously clever idea. But Poe wasn’t a member of the Yale Performance Studies faculty. He was a hack journalist who needed the money.’

Ian gave me a brief, enigmatic look. He would certainly have grinned except for the fear of upsetting Nancy.

‘Plus,’ I declaimed, ‘he was a paedo who married his thirteen-year-old cousin and then wrote creepy stories about it before dying drunk in the street.’ I was getting into the swing of it. ‘And this place parades his doodles and laundry lists around 21like the Tablets of the Law. Shall we go and dig him up and sell bits of his bones in the gift shop? Great horn spoon!’ That was the end of that. Nancy looked as if she was going to have a good sob in the ladies’ loo as soon as the meeting was over. Like I said, I was on fire.

You will note from the above, by the way, that since my early educational failures, I have become quite well read under my own steam. I am unembarrassedly an autodidact, although this is a fact about which I do not like to brag.

Mid-afternoon. The meeting had ended with no announcement having been forthcoming. I was back in my office with a damp flannel on my face.

There was a knock on my door. I cracked it open and took up a defensive position. It was Ian. This was the first bad sign. People who are in charge of you only come to your office if a) they have bad news, or b) they are just passing and suddenly remember something they wanted to ask you. When they want to give you good news, they make you go to them.

‘Hi, Agatha,’ he began. ‘Can I come in? I can, of course, or then again maybe not. Depends on whether or not I could overpower you. Oh dear, that’s highly inappropriate, why am I envisaging that, even as a joke? Don’t call HR, ha ha. May I come in—is the word—may I?’

I forget what I said, but somehow he was in my office. His big body took up most of the space in the room. He looked like he had been a ruggedly handsome prop forward once, in some long-ago public school, but had since gone to seed. He was dressed, as usual, in a shapeless, vaguely military-style jumper and a worn-out pair of slacks that no doubt originally cost 22half what I made in a month. Despite appearances, there was nothing careless about how Ian presented himself. Everything about him, down to his Boris Johnson haircut, was as meticulously calibrated as a jeweller’s scale.

‘How’s the Gladden Green stuff?’

This was a box of junk that had been donated by the Cadigan family of Harrogate, Yorkshire. Mrs Cadigan’s father had recently passed away but had paused long enough to extract a deathbed promise from his family that they would donate the papers of his own father, an amateur writer named Alexander Cust, to a literary archive, where some future researcher would discover their overlooked genius.

I would not have countenanced accepting it, except that this Cust had been, for a period that included the year 1926, a porter at the Pale Horse, outside Harrogate. This was, as I am sure you know, the year in which Gladden Green, the empress of Golden Age mystery (for those of you who have never been to a bookshop or turned on the television), famously disappeared and was after ten days discovered at the Horse. There was just a possibility that there was something good in there—a previously unknown photo of Gladden, a check-in slip with her autograph, some bonbon or other.

‘Haven’t seen it yet,’ I said. ‘Bunner has it in the freezer.’ Old papers have to go in quarantine before we process them, to kill the microbes that might otherwise get out and eat our whole collection.

‘I’d have thought you’d have wanted to get your hands on it,’ he said.

‘I asked Bunner if I could have it early, and she looked as if she was going to cry,’ I said.23

‘There’s gold there, I know it. You have the magic touch.’ Ian had this schtick where he said things in a tone that sounded ironic, but one was supposed to understand that he was serious really. The truth was, though, that Ian didn’t give two hoots about Gladden Green. But he had done his homework Re: on what I was working. He always went the extra mile. ‘I’m so excited; it’s so exciting.’ Was it? Wasn’t it? I couldn’t tell.

Ian was directing the Neele as a second career, having made a good deal of money in fund management. This was just as well, since the Neele paid peanuts. It was anyone’s guess what he was doing here, instead of raking it in keeping gentleman’s hours at a think tank. Did someone, somewhere, have some terrible dirt on him? Or did he just really love old books?

‘Listen,’ he went on. ‘I shan’t beat around the bush. It’s about the curator position.’ He took a pen from the holder on my desk—my favourite Montblanc fountain pen, but I didn’t say anything—and twiddled it awkwardly between his fingers. I ran through some possible outcomes in my head. They were going to do an external search. They were going to give it to me, but there would be no raise. They were going, god forbid, to make me share it with Bunner. What else?

‘We’re going to go with Nancy,’ said Ian.

I said nothing, as oceans of time seemed to pass. But Ian did not, on examination, appear disturbed, so I supposed it had been only a second or so. The Crooked Man! Ian had been the Crooked Man all along!

‘Nancy’s only been here six months,’ I said, in what I hoped was a neutral voice.24

‘I know. It’s probably an idiotic move, god knows. She’s a child. There are a couple of things I’d like to say, though.’ He had practised this before he came. ‘You really mustn’t think this has anything to do with your ability as an archivist. Nothing at all. You’ve been absolutely exemplary here.’ He twiddled the pen some more.

Eff him.

‘These senior positions, they’re all PR jobs nowadays, no matter what the job description says. Nancy’s not going to be looking after collections. Not really. She’s going to be schmoozing the bluehairs, glad-handing, raising filthy lucre. She does have a truly unique—they call it handshakefulness, rather horribly.’ That was what they called it, was it? I thought of the way she touched the forearms of male donors and laughed at their jokes while they fantasized about setting her up in a West End sex flat.

‘You don’t want to be doing all that, not really,’ said Ian. ‘You wouldn’t be able to tell everyone off about liking Edgar Allan Poe.’ He smirked ruefully.

So that was it. Had they mistaken my plain-spokenness for a lack of tact? Had they found me—annoying? It seemed hardly possible.

‘This is balls, Ian, you know that,’ I said.

‘I know, dear. If you’d rather take the opportunity to move on, we would quite understand.’ Smug fool. ‘You can punch me in the face if you like.’ He smiled again.

Quite so. What was there left to do? It was done. Even though a hasty cost/benefit analysis of hitting him in the face yielded a negative recommendation, I considered it for a good few seconds. But no. ‘OK,’ I said. ‘OK, OK.’25

For some reason, Ian didn’t leave. ‘I’m sorry,’ he said, ‘this is awkward, but are you saying you are or are not going to punch me?’

‘God, no,’ I said. ‘I’m telling you to eff off.’ My headache had become really quite acute. Only after he had left did I notice that he had taken my Montblanc pen away with him.

3

The next morning before work, the reality of the situation in which I was about to find myself vis-à-vis Clara began to hit home. My mother needed full-time care. The help-card arrangement barely worked as it was. And now there would be no Murgatroyd either? If I wasn’t careful, I would find myself back in Palmers Green permanently.

I decided to telephone my brother Heri and try to bully him into paying to put Clara in a home.

Once I made it past his assistant, which was no small feat, I tried to take him to task. I told him that the time was past for his lazy estrangement. I told him that I had it on good authority that he was one of Britain’s Richest Doctors, and that doctors were renowned in the first place for the healthy size of their salaries, to wit, this wasn’t some kind of ‘tallest dwarf’-type accolade. And, I told him, he had Responsibilities towards his family.

He put on his extra-calm and reasonable manner, so I would know that he was Handling Me, and said oilily that, while he was indeed fairly well off on paper, like many well-off people he in fact had very little cash on hand, and that if he were to attempt to raise funds for our mother’s care, he would be obliged to liquidate certain assets that were currently held in the form of property.

He meant my fancy flat in the Gatehouse. The Gatehouse, the brutalist wonderland the Corporation of London had 27created in the 1970s to fill one of the swaths the Blitz had cut across the City. Home of the Museum of London, the Gatehouse theatre, and the great high-rise towers: Chesterton, Conan Doyle, and Sayers. Plus, the Neele Archive. I could walk to work.

‘It’s in my name, Heri!’ I said.

‘A technicality,’ he said. That bull’s pizzle! I had always hoped—assumed, even—that he, like me, saw the money he had paid for the flat as a loan in name only. I would certainly never be able to pay it back without selling up. Nowadays, everyone wanted to live in the Gatehouse, and flats sometimes went for more than £2,000,000.

When I moved in, in 1997, everyone hated it. Today the complex had a gift shop selling socks with pictures of the towers on them, and the flats’ weird square vertical sinks are considered Design Classics. People who got rid of them in the eighties now spend large amounts of money to retrofit them. I myself, who has excellent taste, had always loved the sink. Sometimes I would stare at it for minutes at a time of an evening. This is all to say that I was jealous of my flat. It was a fetish onto which, in the light of the failure of every other aspect of my life, I had projected significant portions of my self-esteem. Heri knew I would do anything rather than let him sell it.

‘Heri, you are a bull’s pizzle,’ I said to him, and hung up. I consoled myself with the knowledge that I had done something in the service of finding help for my mother, but I was no closer to solving my problem.

I had to go to work. In a foul mood, I headed out onto the access deck, where I nodded at Mrs Hernandez, my next-door neighbour of a decade’s standing. (I did not actually know if she was called Mrs Hernandez, but in my mind I had so designated 28her.) ‘You look as if you have been sucking on a lemon, Miss Dorn,’ she said cheerily. I gave her the least offensive gurn I could muster. Then I took the lift down and made for the Neele.

At work, we had our monthly meeting with Arise.

You’ll remember that Arise was at that time trying mightily to turn the entire Gatehouse complex into their London base of operations. The Neele sat in the middle of the Gatehouse. Everything on the original site had been obliterated. All except the Neele.

Both the British government and the Corporation of London, which owns the rest of the Gatehouse, had been really quite keen to make Sir Ed Ratchett’s London ‘campus’ happen.

In the early nineties, when Ed (without the ‘sir’) had looked a little more like a computer nerd and a little less like a Hollywood beau, he and his business partner Aristide Leonides had founded Arise (AR for Aristide/Ratchett, plus Rise, you see), the first viable online bookshop of the Internet era. Then in—when?—ninety-seven? ninety-eight?—Aristide Leonides had died—young. I remembered that there had been perhaps something unseemly about his death, but I couldn’t remember the details. Anyway, after that, the whole thing had exploded into an unstoppable retail behemoth and—more importantly—an emphatic marker of Britain’s membership of the world’s economic Premier League. It was no wonder the government didn’t want the likes of us standing in their way.

Plus, Sir Ed had proposed the creation of a series of free schools, to be built in low-income areas, the salaries of whose teachers, and the standards of whose buildings, would be far higher than could otherwise be afforded. All the company asked 29in return was the exclusive right to manufacture and sell to these schools all the books and equipment they would need. It felt churlish to point out that the government could build the schools itself if Arise would simply pay its taxes.

We were all that was standing in the way. The Neele led a charmed life. The land on which it was built had been given outright to some ancient Neele, or Neil, or McNeill, by William the Conqueror himself, and so it was extraordinarily difficult to get rid of it. Not even Hitler had been able to do it.

This kind of thing happened to us all the time, and the proper way to deal with it was to pretend to consider the proposal for a few months until it went away.

To that end, I would need my best pen back, in order to take pretend notes. I stopped by Ian’s office on my way, in order to fetch it. Ian was just coming out, but, oddly, hurried to shut the door as he saw me coming.

‘I was hoping to retrieve my fountain pen,’ I said. ‘You walked off with it yesterday.’

‘Did I?’ said Ian. He looked appalled.

‘Could I fetch it from your office?’ I said, gesturing at the hastily closed door.

‘What?’ said Ian. ‘No! I mean, I’ll bring it with me to the meeting.’ I stood awkwardly for a moment, until it became clear that Ian wanted me to leave before he would reopen his office door, so I did. That was curious. I wondered what Ian had in there that he didn’t want me to see.

Especially since, once he did arrive at the conference room, he did not have my pen with him.

When I got to the table, there was a cup of tea waiting at my spot. As I went to sit down, Bunner appeared at my elbow 30with the expression of a bellboy waiting for a tip. ‘I thought you might need a pick-me-up, Agatha,’ she said, too loudly. I wished she wouldn’t do things like this. Quite apart from the fact that I am sure I have told her I hate tea, it was a pitiful attempt to buy my affection. I cheers-ed her with the tea and tried to look appreciative.

Oliver from Arise kicked things off as always with one of those overhead-projector presentations he called a slide deck. The first one read ‘Now’ and featured a group of sad waifs and strays huddled around a harried young female teacher with a dog-eared textbook. Oliver tended to make the slides more melodramatic each month. This time, one of the waif-and-strays was actually crying. On the right-hand side was a picture of the Neele, in which the lighting had been adjusted to make it look sad and depressing.

The next slide read: ‘The Arise Future!’ In this one, the children all had shiny new books. The teacher, who had acquired the happy-idiot look of a woman in an advert for sanitary products or yoghurt, was sketching inspirationally on a tablet whose screen was mirrored at the front of the class on a cinema-sized monitor.

The other half of that slide was a picture of me in a crimson convertible, pulling up to a shiny new glass-and-steel building surrounded by nature. The caption here read: ‘The Neele Sunningdale’.

The old hat I typically wear while travelling to and from work is scarlet, but in this month’s picture they had recoloured it crimson to match the car. Sometimes I text Bunner during these meetings. I tried it now: ‘They’ve tinted my hat to match the car LOL.’

It seemed to me that Arise was on the verge of giving up. 31That picture of the sad children reeked of desperation. I texted Bunner so, but again got no response.

But instead, at about the point where these meetings usually wrapped up, Oliver paused, with the air of a girlfriend about to announce that we needed to talk.

‘So look,’ said Oliver, ‘I should let you know that our new GC has recommended that we change course and pursue compulsory purchase.’ He sounded sad that we were going to have to give up our little get-togethers.

‘Oh, I shouldn’t think so,’ said Ian, as if it were a matter of opinion. ‘We’re really going to go back down that road? I don’t think I see that what made it a bad idea last time doesn’t still make it a bad idea this time. The Neele is a national treasure. You’ll get crucified in the media, won’t you?’

‘Well, OK,’ continued Oliver, ‘but here’s the thing. Our new GC doesn’t think the Neele is a national treasure. He thinks no one has heard of you, except for that Edgar Allan Poo nonsense a few years back. And you know I like all of you very much, so maybe this is just my bad mood speaking, tell me to shut up or whatever, but I’m inclined to agree. I think no one cares about the Neele Archive at all.

‘And you know what else? I think if it goes to the Supreme Court, we’ll win. It’s in the public interest, a large majority of the landowners want to sell, there’s a substantial contribution to the local community. I think we’ll edge it.’

‘Well,’ said Ian, whose poker face was intact, ‘we’ll prepare a response for next month’s meeting.’

‘Oh, this is awkward,’ said Oliver. ‘I was hoping we might be able to come to terms without getting to this. We’ve actually already filed the motion for compulsory purchase. I was 32rather soft-pedalling it, to give you a chance to save face. So we shan’t be meeting next month, I’m afraid. As I say, we’re taking a different course.’

‘I don’t see Bill going for that,’ pressed Ian. A little flush had emerged above his collar.

‘In fact,’ said Oliver, ‘Sir William has assured us that the Home Office will endorse our motion.’

‘We’ll see,’ growled Ian, but Oliver cut him off.

‘We’ll still move you out to the sticks if you like,’ said Oliver. ‘As long as you don’t misbehave about the compulsory purchase—and, as we’ve said many times of course, the new building we’re proposing for you is a really wonderful facility, far superior to this one in all sorts of regards. But let’s say we essentially have the decision: Arise will be buying the Gatehouse.

‘In any case,’ he continued after a pause, ‘it’s been absolutely delightful working with you all. Maybe the book world will bring us all back together one of these days?’

As Oliver was packing up his things, I finally got a text back from Bunner. ‘Is this a disaster?’ it read. When I looked up at her, she was all stunned and sad; everyone was. It was indeed a disaster.

4

I mentioned the Crooked Man before. Let me tell you what that is all about. Reading about Gladden’s idea of the Crooked Man at university is how I became a Green enthusiast in the first place. Is it embarrassing if I show you a passage from a book?

You would be having a lovely dream—you might be at a picnic in the park or a boat party. Suddenly, you would get a queer feeling. Somebody at the party was not who he said he was. Somebody at the party was the Crooked Man. You could not tell just by looking. The Crooked Man would reveal himself in his own time. Until then, though, you were terrified. All the joy went out of the day.

Anybody to whom you talked could be the Crooked Man. Mummy. Auntie. Daddy. Your best friend. You couldn’t relax and play.

Then you were talking to Mummy. You realized that all along you had known it was Mummy. Her back began to hunch over. She looked down at you and you saw her terrible steely blue eyes from beneath the brim of her black hat. Did Mummy wear a hat? Strange how one had never noticed before. And then, from the sleeve of the long black coat in which she was suddenly wrapped—out came the horrid stump! It wasn’t Mummy! It was the Crooked Man! And you woke up, knowing, always having known, that nothing was what it seemed to be.

34I mean, I don’t know what to say about it. I just think it is the truth. This was how the world had felt to me for as long as I could remember. Nothing was what it seemed. The Crooked Man. Of course.

It’s funny. There are no supernatural characters in Gladden Green novels. Even this one, the Crooked Man, is merely a figure from a recurring dream one of her protagonists has. But this weird character epitomizes the appeal of Gladden’s work for me. The world of her novels looks benign at first glance. But never believe it, no matter how much you might want to! The secret to life is never to be lulled into thinking things are OK. Always be on the lookout for the spectre, because he’s always there. That’s Crooked Man thinking.

Do you remember the television adaptations they made of the Père Flambeau stories in the 1980s? The title sequence had things just right. It featured a series of sketches of Steeple Aston, the village where Flambeau lives. Each one would at first glance depict a bucolic scene—a cricket match, a country house—and then the camera would zoom in and reveal some hidden horror. Behind the wicket lay a mangled corpse. The face of the woman standing in the window of the manor bore an expression of such vitriol that it made one gasp. This vision—not merely that the world is riddled with evil, but that its evil is both always present and always lurking just out of view—well, I stand in awe thereof.

And so I became a Gladden Green enthusiast and then, once I arrived at the Neele, a Gladden Green expert—though on the sly, since I do not really like the idea of anyone knowing that anything matters to me very much. I especially did not want them knowing about my love of what they might 35wrongly consider the subliterary corpus of a conceited old sow.

For I should say, even now, people mostly do not take Gladden Green seriously. But then, people are idiots. And Green herself did not help matters. The Pale Horse scandal made her an unsympathetic figure after 1926, and she did little to repair her public image. Instead, she seemed to cultivate the aspect of a petty-minded Little-Englander. In later life, many of her public pronouncements concerned the twin disgraces of how much tax her father had had to pay while she was growing up, and how much she now had to pay as the world’s most successful novelist. She dressed like an embarrassing maiden aunt, wearing cat’s-eye glasses and fake-fur hats with polyester bows. The only thing anybody liked about her was Flambeau, but Green would go on television and tell everyone how much she had grown to hate her detective. In a letter to The Times Literary Supplement in 1972, she made fun of the name of an up-and-coming Indian novelist. She proclaimed her admiration for Enoch Powell. Feminist publishing houses and graduate students did not find it congenial to reclaim her as a lost genius, and, besides, she was far too successful ever to have been ‘lost’.

But I bought us many things, somewhat sub rosa, so that the Neele now had amongst its holdings one of the finest collections of Green first editions, holograph manuscripts, and other materials, in the world. (Fun fact: I purchased the aforementioned 1980s sketches from the Flambeau title sequence for the Neele ten years ago; I superstitiously keep them in a portfolio with a lock on it, in particular to stop the vitriolic lady from getting out and murdering me in my sleep.) Ian and the others 36knew that I bought Green stuff, but the full scope and value of the collection was something of which only I was aware.

If you have been sufficiently careful not to allow yourself to hope for something too much—a promotion, for instance—it is easy enough to manage when you do not get it. I had, I admit, been caught off guard by the news about Nancy, but two days later, I was fairly well along in the task of stuffing my disappointment into the memory hole. I was almost all set to hunker down into my bitterness and channel what fury I could not repress into creating a five-year plan for getting even with Nancy and the rest of them.

But my fortunes were about to change with astonishing speed.

When I got to my office, I found that Ian was there.

‘Hello, Agatha,’ he said. ‘I hope you don’t mind my barging in.’ I did rather, but it didn’t seem like the moment to say so. ‘I realized,’ he said, ‘that we didn’t make much headway on the subject of the summer exhibition in the end. I got a good idea of what you didn’t think we should do, ha ha, but I wondered if you had any sense of what we might do instead?’

This was an odd subject for him to bring up, especially with the threat of eviction hanging over our heads. I wondered if Ian was trying to make amends for the whole promotion situation by making a point of valuing my opinion. In fact, however, he had merely succeeded in putting me on the spot.

‘Well,’ I said, casting around for an idea and finding that only one immediately came to mind. ‘We’ve never shown any of our Gladden Green material. I wonder if that might be popular. I’ve been acquiring in that area for some time now, as you know.’37

‘Gladden Green,’ he said, musing on the idea. ‘That’s a thought. She is popular. Is she a little too popular for a Neele exhibition, if you see what I mean?’

If Ian was trying to placate me, he was making a mess of it, for my hackles went up immediately.

‘I think she is very much underrated as a serious author,’ I said.

‘Of course, of course,’ he said. ‘I know she is a particular passion of yours. Well, it’s certainly an idea to give some thought. And you have these new papers coming in.’

As if on cue, there was a knock at the door.

It was Bunner, carrying the very papers Ian had mentioned. ‘Agatha!’ she cried in delight. ‘I have the box from Harrogate. And Ian has had the most wonderful idea.’

Ian looked slightly shamefaced, as if he suspected that I would not find his idea to be wonderful. ‘It’s just,’ he said, ‘I wonder if you would share processing the box with Nancy?’ I looked at him with a deadpan expression. So that was what he had been here for. ‘I want to get her more familiar with our protocols,’ he said. ‘And besides,’ he went on in a stage whisper, ‘she’s rather terrified of you. She just wants to be friends.’ This was an obvious lie. I had been justifiably stern with her at the staff meeting, and now she was going to interfere with my project as revenge. It was just the kind of petty viciousness in which she would engage. ‘I’ll tell her to come down when she’s got a minute then, shall I?’ he concluded—then he swept out.

‘Thank you so much for waiting for the box, Agatha,’ said Bunner. ‘I’m sorry the accession protocols take such a long time.’ Bunner could be quite passive-aggressive when she wanted to be.38

I looked down at the box. I had not had high hopes for its contents and had been planning to procrastinate, but between Ian’s dismissal of Gladden Green and the news that I was going to be sharing the project with Nancy, it suddenly became a matter of urgency. How dare Ian suggest that I wait for Nancy to lollygag all day?

I lifted the lid, then the first couple of leaves. Two stanzas of pious doggerel, eheu, inscribed on the verso of a hotel-wide memorandum about the prompt laundering of linens. The next was similar. Resentful tetrameters backed with receipts and reminders from the Receptionist and the Clerks of this and that, written in what was only-too-recognizable as the universal language of workplace passive-aggression. ‘Per our several previous conversations…’ ‘The Bell Captain wishes to remind the Porters…’ ‘Your cooperation in this most significant matter is greatly appreciated…’

In 1911, there seemed to have been much to-do over a visit from Harry Houdini and his entourage. Cust wrote in paranoid fashion about his suspicion that the Bell Captain, one Mr Scaife, had deliberately attempted to withhold from him the opportunity of meeting Houdini out of spite, in order to thwart the blossoming of his literary career. Nevertheless, apparently Cust had triumphed in the end by managing to obtain Houdini’s autograph, along with a written endorsement (neither of which could be found in the box). Although I remained unsure of how meeting Houdini was supposed to be of help with one’s literary career.

Next, a handwritten letter: ‘Dear Mr Cust—for I am told that this is your name—For the services my requesting of which you have graciously humoured, much, indeed, incalculable, thanks’.39

This sounded more interesting.