8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

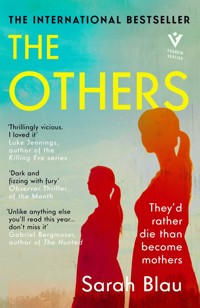

A DARKLY FUNNY INTERNATIONAL BESTSELLER WITH A CULT EDGE, ABOUT CHILDFREENESS, CONSERVATISM AND MURDER, PERFECT FOR FANS OF MY SISTER, THE SERIAL KILLER, LULLABY AND THE FALLING AN OBSERVER THRILLER OF THE MONTHA SUNDAY TIMES CRIME CLUB PICKA GRAZIA BEST BOOK OF THE YEARA CRIMEREADS PICK 'Thrillingly vicious. I loved it' LUKE JENNINGS, AUTHOR OF KILLING EVE 'Twisted, dark and fizzing with fury' OBSERVER THRILLER OF THE MONTH 'Unlike anything else you'll read this year' GABRIEL BERGMOSER, AUTHOR OF THE HUNTED 'Dark, tense, and creepy' KAREN PERRY, AUTHOR OF COME A LITTLE CLOSER ____________ FOUR WOMEN. ONE FATAL PROMISE. Dina, Ronit, Naama and Sheila: the Others. As students, they chose to be different - bound by a pact never to have children. Even as their friendships fell apart, Sheila kept her promise. Now, years later, a serial killer is on the loose in Tel Aviv. Each victim is found with a baby doll glued to their hands and 'mother' carved into their forehead. The vow the Others made long ago lands Sheila at the heart of the murder investigation - but is she the next victim, or the prime suspect? Twisty and very funny, part Twin Peaks part Killing Eve, this psychological thriller was an instant bestseller. If you like books with a difference, this wry page-turner is for you ____________ FURTHER PRAISE FOR THE OTHERS 'Singularly creepy' New York Times 'The narrative twists with ironic relish' Sunday Times Crime Club 'A dark and funny page-turner' Ayelet Gundar-Goshen, author of Waking Lions 'A razor-sharp thriller' Daniela Petrova, author of Her Mother's Daughter ____________ READERS LOVE THE OTHERS 'Wow, this book was such an entertaining read, I couldn't wait to finish it' 'It certainly deserves its spot in the list of top crime fiction novels of 2021' 'The writing is funny as hell' 'A sort of Israeli feminist version of Bridget Jones, [Sheila's] humorous asides are hilarious' 'A once in a lifetime kind of novel. . . Simply brilliant'

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

3

5

In loving memory of Uri Orbach

6

Contents

1

By the time that phone call from the police came, I was ready.

A gentle male voice asked if he could pop by for a quick questioning. That masculine energy threw me off for a moment. Rehearsing the scenario over and over, I had always imagined a woman, the kind with a gravelly, matter-of-fact voice. I always imagined her a bit tired, maybe after a long shift, most likely a mother. They always are.

And she would always react the same way, downright rattled by the gruesome murder, gruesome and ritualistic, God, the horror! Before pulling herself together and remembering why she had called me in the first place.

“Age?” she’d ask while typing. “Married? Kids?” And I’d reply to the two last questions with the usual “no,” but this time with relief sweeping through my body.

No, ma’am, no kids.

According to the police report, Dina was murdered at 1 a.m.

The papers said it happened in “the dead of night,” and catalogued all the grisly details, but the police report was worse – trust me.

The papers also said the victim was a professor of gender studies, and the murder was described as having “unique characteristics,” by which they probably meant the fact that she was 8found hog-tied to a chair in her living room, the word “mother” carved into her forehead, and her dead hands clutching a baby doll.

What they didn’t mention was that it was one of those reborn dolls you see on British TV shows featuring people with “peculiarities,” who treat their dolls like real babies. These are usually after-hours shows, broadcast in “the dead of night,” viewed by people like me with a curiosity tinged with horror. I’m not going to become one of those people, right? I wouldn’t rock a doll in a cradle and tell my guests, “Shush! He’s having trouble sleeping,” right?

The doll found at the murder scene had a round face, puckered red lips and clear blue eyes with lifelike lashes.

What was mentioned was the struggle to pry the doll from the victim’s hands. At first they thought it was rigor mortis, but then discovered the baby was glued to her. One sentimental journalist waxed poetic about how she looked like “a mother clinging to her infant, refusing to let go.” Despite my best efforts, I couldn’t imagine Dina clinging to anything, let alone an infant. No, no, it had to have been glued to her.

I guess Dina would have been pleased to know that her list of accomplishments extended over quite a few sentences. They cited the PhD she had obtained at such a young age, the dazzling lectures that drew packed audiences and the brilliant essays, highlighting, of course, the one about childfree women in the Bible, the one that had cemented her status as “one of the most prominent and polemical feminist theorists of our times.” They also noted that she had chosen neither to marry nor to have children, and had become a leading advocate for this “controversial movement.”9

They did not mention the resistance of her skin during the attempts to yank the doll out of her hands, resulting in her having to be buried along with it, the doll pressed up against her.

And I couldn’t help but think, There you have it, Dina, you’re finally a mother.

2

My falling-out hair is gathered in clumps in the corners of every room.

The whole apartment is filled with boxes and hairballs. I keep tripping over the former and stepping on the latter. There’s your usual hair loss, the one women’s magazines will subtly refer to as “normal from a certain age,” and there’s the other kind, a product of my own pulling and yanking. At least I don’t swallow it. Every now and then I’ll stumble over an article about a giant hairball surgically removed from the stomach of some neurotic young woman, and in the photo accompanying the article, it always looks like a hairy baby monster.

I still think about Maor’s parting remark before leaving, “Your hair is all over the house, do something about it, it’s gross.” Bam! The door slams shut, kicking up a tiny hairball past my face.

For the first time in my life, I considered swallowing it.

I’m sweeping the apartment with a new silicone broom; I bought it yesterday, dragging it with me all the way home, attracting the curious gazes of passers-by, as if they expected me to ride it. They should be grateful it’s a shiny, sterile silicone broom and not the giant straw witch one I got for fancy dress at Purim. Although, it is possible that no one was actually looking at me and that I was merely imagining the scrutinizing stares, and even more 11likely that it was just that damn guilt following me around like a gloomy companion.

The apartment is full of dust; I cough and my eyes well up. My image in the mirror seems too flushed and dishevelled. Not good. I have to look calm and collected for the visit; the detective might have sounded young, but not stupid.

Most importantly, I have to stop with the remarks that come pouring out of me when I get nervous; sometimes I think it’s momentary fits of Tourette’s. Otherwise there’s no explaining why, when the detective sensitively enquires whether I’ve been feeling afraid since the murder, with all the frenzied fuss kicked up around childless women, that instead of muttering a feeble yes, I feel compelled to share that “The scariest thing about this whole business is that they finally made a mother out of her.”

No, the silence on the other end of the line did not bode well.

A brief knock on the door and in he comes, almost tripping on one of the boxes I failed to move aside in time, and now he’s smiling awkwardly while reaching out for a handshake.

He’s young. Unreasonably young, with that boyish smile that brings a dimple to his left cheek, just like Maor’s dimple. Like Maor he’s carpeted in fine stubble, and those bright eyes, just like Maor’s, study you to reach private conclusions he has no intention of sharing.

Oh, yes, it’s definitely there, the resemblance, especially in the particular green of their eyes, and the lashes that go on forever, and the crooked smile aware of its effect on you.

This time it’s a real resemblance, not the imagined kind right after a break-up, when every man (including the old broom 12salesman) looks like a doppelgänger of the absconding lover. Don’t go there, Sheila, be smart.

“Pleased to meet you, I’m Micha,” he says, his hand still suspended mid-air. I notice a tattoo of a sentence in thin Rashi script across the tender part of his wrist. I can’t read it, but I don’t need to in order to make my observation: erstwhile prince of the religious Boy Scouts. In my mind’s eye I see the absent kipah resting atop his head, the excessive self-confidence making up for a late-blooming masculinity.

“Moving out?” he casually enquires while sitting down on the freed-up part of the couch, his eyes casting about, studying the contents of the open boxes.

“Just moved in,” I reply while we both simultaneously catch sight of the small baby doll poking out of the box behind the door. You idiot!

“Still playing with dolls?” The light-hearted tone doesn’t fool me. His eyes are devouring the doll, its one eye closed and the other looking straight ahead with an icy blue stare. It looks like someone punched her.

“A gift from my ex,” I reply. “Sort of a joke.”

“And what does it mean? The expectation of a baby together?”

A baby? Dream on, Sherlock.

“Not exactly,” I say, dragging out the words. “More of a joke about him being a baby.”

“Well, most women think all men are babies.”

And there it is again – his Boy Scout guide’s smile, instantly delivering me back to my days as enamoured Girl Scout, because some patterns are so deeply ingrained in us that we immediately fall back into them, like eternal roleplay, and your part never 13changes, no matter who you are or how old, because the role was tailor-made for you from day one.

“He really was a baby,” I explain. “Only twenty-six.”

“Huh, nearly my age.”

And already he regrets sharing this information, but his mind starts racing, doing the math, because if Dina and I were in college together, that means I’m at least how old…? His mind is busy calculating, his eyes sweeping over me and that mouth quietly mumbling a few polite words that whiz right past me… Because I instantly recognized that wandering gaze of his, and I know all too well what’s running through his mind. I know that if he wasn’t on the job right now, he’d already be informing me that he too had dated an “older woman,” because they all do at some point, especially the cute ex-Orthodox hotties, and it always ended “not so well, but we’re still on friendly terms.” Pfff. But he wouldn’t say that, would he? He’s here to try to glean information about the murder from the victim’s best friend – former best friend – isn’t he? And he seems like someone who can watch his mouth.

“I had a relationship with an older woman too.”

Well, well! You do surprise, kid, although I’m not so sure you did in fact date an “older woman,” because a real older woman would have taught you not to call her that, a real older woman would have had your dumb, pretty head if she heard you talking about her that way. Obviously, you would have had to pretend you’re both the same age, and if you accidentally let a wayward mum slip, you had to immediately laugh it off, I was just kidding, Mum.

“I mean, not older,” he rushes to correct himself, “just older than me. She was about your age, thirty-something?”14

Okay, stupid he ain’t.

“I’m forty-one.” You’ll be forty-two next month, and you know that; each year counts, and you know that too.

“So my girlfriend was your age.”

Hmm… he isn’t backing out, interesting. I wonder whether this is some kind of manipulation, to butter me up to get the information he wants, but that attentive gaze is still there, and so is that soft-looking, beautiful mop of hair. On the other hand, we haven’t exchanged a single word about the murder. But that dimple won’t stop flashing in front of me, followed by that smile that’s making me weak in the knees again, so much so that I feel myself melting, fading away, lowering my eyes to the tattoo on his delicate wrist and asking, “Did it hurt?”

“Like hell.”

“Anything to drink?” Go to the kitchen before you make a huge mistake, go, remove yourself from his presence.

“I’d love some coffee,” he says, just when I remember I have nothing to offer but tepid tap water with a distinct metallic tang – a taste I have yet to acquire. I serve him the water in a sticky glass, which he studies at length.

“Don’t worry, everything’s kosher here.” I can’t help myself.

“It doesn’t bother me,” he replies with a curious gaze. “It’s been years since I bothered myself with such things.”

“I have a sophisticated ex-Orthodox radar,” I explain, an answer that usually satisfies them.

“You’re the first person to be on to me this quickly,” he admits.

“Really?” I ask, even though I’m not surprised. “It’s so obvious, it’s like the kipah is still on your head.”

And he reaches out, not to the top of his head to check if it 15has sprouted a kipah, but to the box behind the door, from which he pulls out the small baby doll. Am I imagining it, or has its closed eye opened slightly?

“You know, this doll looks a lot like the one glued to Dina Kaminer’s hands,” he says without looking at me.

“I didn’t glue anything to anyone, if that’s what you’re insinuating.”

Bad answer. Very bad answer, because now he’s peering at me with that scrutinizing gaze, the one I’ve been worrying about from the moment he stepped into my apartment.

You idiot.

“If you haven’t noticed, I didn’t ask you if you glued anything,” he says. “I haven’t even asked you where you were two weeks ago on Wednesday at 10 p.m.” His voice is very quiet.

“Wednesday at 10 p.m.?” 10 p.m.!

“One of the neighbours had just stepped outside and heard Dina opening the door to her apartment and saying to someone, ‘I’m glad you came,’ but she could barely make out the voice of the person who replied. She’s almost convinced it was a woman, but…”

“But that doesn’t fit the profile of the anti-feminist-anti-childfree-woman murderer you people built,” I say.

“Good observation,” he says and courageously sips his water, pretending it’s not revolting. “So how about I ask you now where you were Wednesday at 10 p.m.? Would that be okay?”

And once again he flashes that smile of his, all too aware of its effect on me. With an expression both innocent and smug he leans back on the couch when a grating squeak suddenly sounds from underneath him, and he leaps up, spilling his water onto his trousers.16

The damn doll! Her face, now squished, sends me a mocking smile.

Before he leaves he’ll get to hear that on Wednesday evening I was home watching TV, “without a shred of an alibi, but it’s a known fact that the biggest criminals always have the best alibis.” He’ll nod in agreement, ask about my relationship with Dina during our college days, hear how “we weren’t in contact at all in recent years, you know how it is, life just took us down different roads,” a line uttered in such a convincing tone I’d almost believe it myself; a few more dimple-revealing smiles. A few more of my attempts not to stare at the wet spot on his trousers, a few more gazes I’d never imagine I’d receive from the long and oh-so-young arm of the law, and that’s that, we’re already at the door.

He stands close to me, almost leaning in. I feel that magnetic field created between two people whose mere acquaintanceship will lead to disaster, and I shudder.

“So now what?” I ask.

“This is when I tell you that if you recall anything that might be of any help, call me.” He’s very close right now.

“Ah. This isn’t when you tell me I can’t leave town?” Something about his look just begs for wisecracks.

“I’ve seen those detective shows too,” he says. “And besides, you already skipped town.”

Another one of those nostril-flaring smiles, another brushing of his hand over his soft, thick hair, and he turns to leave. The door slamming behind him sends a tiny hairball hurling right into my mouth; I spit it out and hear the familiar giggle, dumb baby. The voice is Dina’s.

3

He was right, obviously, the fledgling detective. I left Tel Aviv in the nick of time.

Too many women like me have walked the streets there – all of us good-looking, polished and prim, clever, sharp-edged, hovering like butterflies and prickly like a fertility-test needle, all of us ticking time bombs, tick-tock, tick-tock, no tot, no tot.

Last week, during a lecture called “Childfree by Choice: Women without Children,” held at a bar in Tel Aviv, a doll was tossed into the crowded room; it was one of those cheap, ugly ones, without eyelashes. It was naked, and the words “Mummy dearest” were written in red ink on its forehead. Once the hysteria died down, virtually every woman in the bar took a photo of the little dolly and posted it on her Facebook page, along with a withering indictment of police incompetence.

The perps were caught two days later, two boys who were so worked up about the ritualistic murder, about the growing frenzy and mostly, by their own admission, “about the possibility that finally we have a serious, creative killer in Israel,” that they decided to pitch in with their efforts. In the newspaper photo they looked like a couple of Moomins, soft and spongy, and I wondered which of the two had undressed the doll. I’d put my money on the ugly one.

*

18And Dina was there, everywhere you looked there was Dina, or rather, Dr Kaminer – in those flattering profile pieces, with heavy-handed hints about her private life (under the guise of investigative journalism), in the eulogies by her colleagues and in the familiar press photos. They kept publishing the one in which she was caught grinning, looking ruddy and wild, her smile – revealing the gap between her front teeth – slightly silly, and more than anything, very out of character.

I have no doubt that if she were still alive, she’d be calling the editor to demand a more appropriate photo, and her demands would be met. She was a master of the art of persuasion: aggressive and charismatic, used to getting her way. But none of that helped her in the end, did it?

That particular article was also dredged up. One of the newspapers reprinted it, verbatim, and I photographed it and turned the image into my screensaver.

I noticed that the people who quoted from the article hadn’t actually read it, but merely regurgitated the same inane assumptions that appeared in the papers without variation. “Did the women in the Bible actually choose to be childfree? Could it be that Dr Kaminer encouraged women not to give birth? Should childless women be afraid to walk the streets now? Could our women be in danger? Could it be? Could it??” and more and more could-it-bes, all similarly poorly phrased, and not one able to hide its smugness.

Tick-tock, tick-tock, no tot, no tot.

A radio host tried to rev up his listeners with the survey question, “Who would you turn into a mother?” He was suspended immediately, of course, but not before suggesting a few interesting 19options, including a famous actress who stated she wasn’t interested in having children, a female director who spoke out against childbirth and an emerging young singer who, in her very first interview, announced she had no intention of becoming a mother.

While reading those three interviews, I already knew that within three years all three women would be smiling at us from magazine covers holding their bundles of joy below the identical caption: “Motherhood has changed me.”

Because by now I know that if you’re not interested in having children, you don’t go announcing it to the world like that. It’s something private and profound, which slowly boils in the depths of your consciousness before simmering to the surface, and even then it won’t stop fighting you till your very last egg dries up – I should know.

“Little witch, little witch fell down a ditch. Come out and play! she cried all day. But no one did, and in the ditch she hid…”

I rush to the window to peek outside, and can’t believe kids still sing that. A few children are standing in a circle around a chubby little girl sprawled on the ground with a scraped knee, chanting at the top of their lungs, repeating the words over and over again. The girl in the middle is confused, not sure whether to laugh or cry. I’d advise her to cry.

I slam the window shut and pieces of plaster come flying off the crumbling wall. It’s the window facing Ramat Gan, a city east of Tel Aviv. The windows on the other side of the apartment offer completely different vistas.

This apartment that I have moved back into is located on a curious spot on the map: right on the dividing line between 20Israel’s ultra-Orthodox epicentre and one of its many nondescript secular cities, an area commonly known as “Bnei Brak bordering Ramat Gan.” Usually it serves as a code name for the residents of Bnei Brak who are more reticent about their background, in which case they’ll say: “I live in Bnei Brak but on the border of Ramat Gan,” even if they live dead in the middle of Rabbi Akiva Street, which is nowhere near Ramat Gan.

But my apartment really is located in between, so when I’m asked “Where are you from?”, I give whatever answer will serve me best. Efraim, the director of the Bible Museum, who finds the fact that I’m religious – even if only tenuously – a hot commodity, will get the answer “Bnei Brak,” while the occasional taxi driver, all too willing to dole out his opinions about synagogue and state, will get the aloof answer: “Ramat Gan.” An answer made to measure. And in general, it’s not bad for a girl to slightly blur her past. I should know.

And there’s another advantage, a secret one.

Whenever I feel the youth draining from my body, feel it on my desiccating skin, my period cut another day shorter, the subtle-yet-palpable slackening of my facial muscles, the bristly hairs sprouting from the tip of my chin, in short, whenever I start doubting my feminine allure, I’ll go moseying along the streets of Bnei Brak, where one always feel lusted after with all those disapproving gazes and reproachful twitches. The slightest bit of cleavage or a skirt cut even an inch above the knee will give you the feeling that you’re Lilith the seductress. It’s a potent youth potion, downright magic.

Maor hated the fact that I was a former Bnei Brak girl; the city seemed inferior and run down to him. When he heard I was 21planning to move back there, he grimaced, couldn’t understand how I could give up living in Tel Aviv. Even when I explained that I was presented with the opportunity to live almost rent-free in an apartment that belonged to a relative, he shrugged. “It would really bum me out to visit you there,” he said.

I guess it really bummed him out. It must have – we broke up even before the move transpired.

I study the pug-faced doll he gave me back then, during the early glory days of our budding romance, when everything gleamed with promise. I should have seen it for the ominous sign it was. When your boyfriend jokes about the considerable age gap between you, it’s going to end in tears and they’re going to be yours.

It’s true that I told him right off the bat that I wasn’t interested in having kids, both because it was the truth and because I wanted to clear that sinister cloud that turns every woman in her late thirties into an intimidation.

He replied that neither was he – a lie! They’re always interested, especially the more selfish ones among them – and he stuck to it for a long time, until he once asked, “Hypothetically, if you did want a kid, who would you have it with?” I, whose sole intention was to compliment him, immediately blurted, “Only with you, my love,” which of course produced precisely the opposite effect. His eyes turned into dark pools of fear. I think that’s when our relationship’s countdown timer started ticking. Tick-tock.

And now, sitting in my rocking chair the next day in the empty apartment like an idiot, I’m holding an ugly doll and waiting for a call from Maor’s deadly double. Maor’s deadly policeman double.22

Every object in the apartment is screaming at you to watch out, but you’re not listening. The walls are boring into you, watching you waiting for the phone to ring, hovering around the device with that hungry expression while the apartment slowly fills with a familiar sensation. It’s called anticipation, and it’s disgusting.

I’m supposed to be glad that I got rid of him so easily, he’s no fool, that Micha, so I’m supposed to be pleased that he went on his merry way without asking the hard questions, supposed to lock the door behind him and spin into a little happy dance. So why the hell am I staring at the phone screen, checking that my battery is still alive? Why can’t I concentrate on anything other than that crazed buzzing in my head? Why? Because you’re a brainless baby, that’s why.

At least good old Google is still waiting for me with open, gift-bearing arms.

I retype “Dina Kaminer” and wait for the deluge of results. No new hits since the last time I checked (an hour ago), no new suspects, no interesting new theories, and the phony concern (with just a touch of Schadenfreude) for the welfare of the city’s single women has been replaced by a few preachy articles about the damage women who keep putting off the decision to have kids are causing themselves blah-blah-blah. In other words, no useful information. I scroll down to the bottom, where the dark world of internet commenters is revealed before me.

It’s incredible how much they hate her. Even like this – murdered, violated, stripped of her dignity and titles – even now they hate her. They always hated her.

And what’s that? A new article. The headline is sentimental – “Dr Dina Kaminer – the mother of all those who do not wish to 23be mothers” – not bad, kind of poetic, I’m not sure what Dina would have thought about it, but I find there’s a certain beauty to it. The article was written by one of her research colleagues, and the comments inform me that she too is childless. They’re on a downright rampage of wrath and contempt, from comments like “fuglies like you shouldn’t have kids,” classic, to “who would even want to have kids with a selfish raggedy hag with a stick up her fat arse,” slightly banal, the usual displays of verbal diarrhoea, and there’s also the tasteful suggestion: “You should find someone who’ll inseminate you and along with his semen maybe pump a little sense into your sterile brains.”

Oh, well, some things never change.

None of these birdbrain commenters has my way with words.

Now, obviously, I wouldn’t dare write a single syllable; I have no intention of letting some police prodigy connect certain dots that could get me into trouble, but in the past, oh, I definitely wrote a comment or two.

Because unlike these Neanderthals with their predictable and limited scopes of knowledge, I knew Dina and knew just where to strike. I knew where it really hurt. Sheila, you little witch.

In one of her interviews, when she spoke about how “the verbal aggression displayed by internet commenters is owed to their anonymity,” I realized she was on to me; I kept on reading and discovered several other sharpened arrows aimed specifically at me. But I didn’t care, at that point my hatred towards her was far beyond reason.

You see, I hated everything that had to do with her. The passive-aggressiveness that was really just aggressiveness, the dark oily hair she kept in a bun, her bulging, black cow eyes, the 24giant breasts she carried with the arrogance of a battleship, her self-righteousness, but more than anything, I hated her voice, deep and purring, a velvety voice that belied the steely punch.

That’s exactly how she sounded that Wednesday evening, when she opened the door and said to me, “I’m glad you came.”

4

“But you didn’t kill her, right?” Only Eli could produce such a sentence so matter-of-factly and calmly.

“And don’t tell me I sound like a bad thriller,” he adds, reading my mind, as always.

I sit in front of him in his office, the day after the police visit, drinking from his Coke can without giving it a second thought. Eli’s office is my safe space, Eli himself is my safe space, this faithful, doglike friend. (Actually, he looks more like a hamster. A tall hamster, a handsome hamster, some might even say attractive hamster, but still, we’re talking hamster here.) And if only I was able to fall in love with him, I would be the happiest woman alive. No, that’s not right, I would obviously be an entirely different person, a person who could fall in love with Eli. Regretfully – I am not that person.

He’s pleasant, Eli, and smart, and his mere presence has a calming effect on me. He’s also patient and has been able to read my mind with uncanny accuracy over the years, but as you’ve probably figured out by now, that’s not the particular set of traits that attracts me in a man. Tick-tock, tick-tock.

Eli was the one who helped me realize, after hours of conversation, that a major part of my unfortunate attraction to young men lies in the fact that everything is still open before them, still shiny and fresh, even if they don’t end up pursuing any of their 26options – the power lying in the very promise is overwhelming. With Eli, for instance, just looking at him I can tell exactly how his life (or our shared life) would look in twenty years, down to the returns on our taxes, which obviously he’d fill out himself. On top of his many virtues, Eli is also the accountant for the museum I work for, but even an office romance isn’t quite exciting enough for you, huh?

About three years ago, after a night of bad dreams featuring all the ghosts of my past, I woke up frightened and dazed and fixed my eyes on the mirror to discover a bristly black hair sticking out from my chin. At that precise moment, the most pointless sentence in the Hebrew language popped into my mind: “Why not give it a try?”

Why not give Eli a try, Sheila? Why do you have to be that way? He’s been devoted to you for such a long time, and it’s not impossible that somewhere, deep inside you, there’s some kernel of attraction. After all, whenever he tells you he started dating someone, you feel the icy fist tightening around your heart, and you just can’t wait for the budding romance to shrivel and die, right?

I promised myself that when we next met I’d look at Eli as a serious object of desire, and somehow managed to stoke myself with such romantic ideations that I couldn’t wait to see him. Unfortunately, Eli, utterly in the dark about his new object-of-desire status, showed up in frayed brown slippers, and when I approached him, the smell they gave off was so repulsive that I instantly and permanently gave up all the “why not give it a try” fantasies.

It was only a few days later that I recalled that Eli wore those slippers often and never before had I given any thought to their 27particular aroma, so I must have ordered my subconscious to find him repulsive no matter what, and the said subconscious, obedient as ever – mainly to my self-destructive orders – simply honed in on the first thing it found.

Eli sips from the can without saying a word about my having nearly drunk it dry. It clinks against his teeth.

“I want to understand something,” he says, “did someone see you arrive at Dina’s on the night of the murder?”

“God, no,” I reply. “If that were the case I’d be busted by now, but apparently someone heard her opening the door for me.”

“At 7 p.m.? That detective told you it happened at 10.” I notice the slight change of tone when he says “that detective.”

“True, but that busybody might have gotten the time wrong.”

“Sheila, you know perfectly well nosy neighbours never get anything wrong.”

He’s right, of course, anyone who’s ever read a detective novel knows there is no one more in-the-know than the nosy neighbour. And no one more dangerous.

I tell him more about Micha’s visit without offering too many details, since I know Eli has it all figured out before I’ve even opened my mouth. He doesn’t ask any questions, knowing he’ll eventually hear more than he bargained for.

There’s only one thing that bothers him. “Dina called and initiated the meeting herself?” he asks. “After all these years? After everything that happened?”

“Yes.”

“So how come she wanted to meet all of a sudden?”

I sink into my chair, unable to bring myself to tell him how it all went wrong, how such terrible things were said, things that 28are painful just to think about, and how, after all these years, she still had the capacity to hurt me. And you honed your capacity to hurt her, so stop whining. You’re the one who’s still breathing.