9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Returning from the wars in Restoration Europe, Christopher Morgan looks to rebuild his life in England and escape the memory of his recently deceased wife - although looking into the eyes of his young son, Abel, Christopher cannot help but be reminded of what he has lost. Over time, father and son develop a strong bond as Christopher establishes community ties in the West Country, having bought a pub and inherited the previous owner's employees. However this relationship is callously torn apart when Abel is snatched by local ruffians and sold overseas. From the eastern shores of Constantinople to the western American isles, time and tide divide the two, and Christopher will sail far and wide to search for his missing son.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 592

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

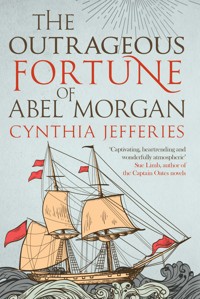

The Outrageous Fortune of Abel Morgan

CYNTHIA JEFFERIES

For my children, Gavin Landless, Rebecca Henderson and Sebastian Goffe In memory of my good friend Caroline Van Oss

CONTENTS

CHRISTOPHER MORGAN

1

It was deep night when the coach reached Dario. Time was lost to him but, somehow, he must have packed his belongings and put himself on it, for he had been carried along for many hours. The coachman roused him with a growl and he realised he was the only remaining passenger. The unmatched pair of horses fidgeted as the coachman untied Christopher’s box and let it drop onto the road. Christopher clambered out. Steam from the sweating horses rose up into the cold night air like mist from a sullen lake in the moonlight. Christopher reached back into the coach for his leather travelling bag. Almost before he had taken it and closed the door, the coachman whipped up the horses. Startled by their lightened load, they set off at a canter, kicking up the road grit. Christopher bent his head against the cloud of dust that engulfed him, holding the edge of his cloak over his mouth. By the time he lifted his head, the coach had gone and the only living thing was a fox, sniffing at a midden before leaping onto a low wall and disappearing under some gorse.

The Rumfustian Inn seemed smaller and older than when he had bought it. The great grey stones of its walls seemed to grow out of the ground, and the low roof undulated under its thatch. In the centre of the building was a broad, heavy door, with a small window to either side. Smoke came from a chimney, and the windows were dimly lit. There was sound, too: the rumble of voices and occasional laughter. Christopher shrank from the idea of company, but he must have a bed to rest his aching bones. And he could be relieved that someone was awake at this hour to give him entry. He closed his eyes for a moment but, open or closed, the same terrible memory was still being played in his head.

Time must have passed. He was chilled now, shivering in his long cloak and dust-grimed hat. He stooped to pick up his bag and left the box in the road.

It was a few short steps to the great oak door. It felt fissured under his hand, like the face of an old man, but the latch lifted cleanly and the door swung wide with hardly a sound. As he stepped in, the lintel knocked his hat askew so that he saw only a portion of the room. It was warm, even hot, with a great fire burning high in the hearth. Christopher had not been so close to such a generous fire since before his exile. Even the King had been forced to be parsimonious with fuel, relying as they all did on the generosity of others. To have a hot fire so late in the night must mean a great store of wood, or perhaps a festival of some sort.

The room was crowded. Surely, almost every man in the village must be here. All were making merry and, at first, the silently opened door attracted no attention. But, as the draught touched the nearest drinkers, they twitched with the sudden chill, turned and saw Christopher hesitating in the doorway. Soon, all were staring at him with eyes that looked alarmed, even hostile, and every voice became silenced.

Christopher knew that strangers were often viewed with suspicion in the countryside, especially so late into the night when few honest travellers were abroad. He might be the new owner of the inn, but he was certainly not expected. Mr Gazely, who had sold him the Rumfustian, had agreed to stay and look after it until such time as Christopher could safely bring his young wife across the country to take up residence. But Christopher looked for him without success. He put his bag carefully down and righted his hat before closing the door behind him. As he turned back to face the room, his eyes met those of a middle-aged man staring at him. The man looked pale and frightened, as if Christopher might be a ghost. This was the servant, William, who, along with his wife, Christopher had bought with the inn to brew and serve beer, cook and generally do his bidding. As Christopher attempted to form his mouth into a smile of greeting, William looked ever more like a dog expecting a whipping. Christopher attempted to speak, but the obstruction in his throat, which had been there as long as his latest sorrow, strangled most of his words. He had wanted to form a reassuring question, but it sounded more like a demand.

‘Mr Gazely?’

The name prompted a murmur from the assembled company, and the switching of attention away from Christopher towards the hapless William. However, it wasn’t William who replied, but a man Christopher had not so far noticed. He sat at a table near the fire, along with an elderly man and several lads who looked so alike they must be of the same family. While most of the other drinkers held tankards, he had a glass of some spirit. A small gold hoop in his ear sparked in the firelight.

‘Gone, sir,’ was his remark to Christopher. ‘This forenoon.’

One of the lads at his table laughed, but the man silenced him with a look.

Before the man could add more, William found his tongue, pushing his way between several drinkers to come close to where Christopher stood.

‘Mr Morgan, sir!’

Everyone redirected their attention to the servant. He blushed deeply but ploughed doggedly on.

‘I’m sorry, sir, not to have recognised you at once, but … we weren’t expecting you so soon …’ He glanced at the man at the table and then quickly away. ‘I do apologise, sir, but I’m sure all of Dario would want to welcome the new owner of the Rumfustian Inn.’

The silence was so solid it could have been sliced.

‘I want no ceremony, William,’ said Christopher, finding his voice, ‘just a bed prepared, for I am very weary. I am sorry to arrive so late and without notice. Did Mr Gazely give word as to when he will return?’

William shook his head and the man at the table cut neatly in. ‘He will not return, sir. In this inn, we are as you see us, rudderless and in need of a captain – but no doubt a bed can be found.’ He raised his glass to Christopher and took a nip of the liquor. ‘SALLY!’

His sudden shout made Christopher jump. He couldn’t recall the man, but he seemed to have no difficulty in acting the host. Perhaps he had been a friend of Mr Gazely.

A young girl, no more than a child, presented herself to the man at the table, but he pointed her towards Christopher and busied himself with enjoying his drink.

‘I will show you to your room, sir,’ she said to Christopher.

‘Thank you.’ Christopher retrieved his bag and followed. The drinkers moved aside to let him past, but none met his eyes or spoke. Christopher wondered if there was some form of greeting he should give them. ‘Perhaps you could ensure everyone gets a drink as a welcome from me?’ He looked at William. Although the man nodded, Christopher had the uncomfortable feeling that it had not been the right thing to say. A quickly stifled guffaw came from the other side of the room. Christopher looked to see who had laughed, but it was impossible to tell. As he turned back to William, the movement slightly opened the front of his cloak. William, being so close, was the only person who could have seen what lay beneath. With terror on his face, he stepped back into a table. A bottle upon it juddered and almost fell. Neither man spoke, but Christopher pulled his cloak across his body once more.

‘My box,’ he said quietly. ‘It is in the road. Please bring it to my room.’

He followed Sally’s flickering figure. At the stairs, she held her candle up to light his way. It was a generous, well-made staircase, but over the years the green oak had settled eccentrically into its foundation, and Christopher had to tread carefully on the sloping timbers. Along a groaning passage and around a corner … Sally seemed to have forgotten him, but the shadows on the wall showed him that she had stopped, and he reached her without mishap. She was entering a room. He hesitated but, seeing her light another candle and then kneel to a laid fire, he surmised that the room must be his.

The infant fire soon caught from her candle. She piled some fragments of peat onto the twigs and then sat back on her heels to await the fire’s progress. She hesitated after adding some sticks, but Christopher was impatient.

‘I can tend the fire. Go … Stay!’

She had stood up and now looked curiously at him, seeming unafraid of her new master.

‘Bring me some beer.’

She reached the door.

‘And perhaps some bread?’

He wasn’t sure if she had heard the last muttered order, but he couldn’t bring himself to call her back again. He took off his cloak and hung it from a nail on the door. Then, after depositing a bundle on the bed, he removed his hat, scattering grit all around. It crunched underfoot as he tossed the hat onto a small table and seated himself in a chair at the hearth. He busied himself with the fire, adding more wood and nudging it with his boot until it fell together in a burning heap. Staring at the fire, he fell into an exhausted stupor while figures danced in the flames, unendingly replaying the tragedy in his head.

The woman might have knocked, but he didn’t hear her. The first he noticed was her sturdy figure standing near his elbow, staring with fearful concentration at the region of his stomach. In her hands she held a pewter mug and plate, both dinted. When he moved his head to look at her, she jumped as if a devil had landed on her back. Beer slopped from the mug and she almost lost the contents of the plate, some bread and a piece of yellow cheese. He hadn’t met her before. She was of middle age and with a face, if it had not been so alarmed, that would have been warm and friendly. It was the face of a servant who looked comfortable with her place and used to knowing more than was required of her.

Christopher found himself flattening the fabric of his shirt to his chest in response to her staring. ‘Is something amiss?’

‘No, sir.’ She sounded more puzzled than convinced as she moved to the table, where she laid down her burden. ‘You asked Sally for beer, sir, and I thought to bring you something to eat, in case you were hungry.’ They stared at each other for a moment, each elsewhere in their thoughts. Being a servant, she recovered herself first. ‘I’m Jane, sir, William’s wife …’ She was trying to keep her eyes on him, but he could see that they kept darting away, examining the room and especially his belongings.

‘Is William attending to my box?’

She looked away from his cloak, hanging as it was like a dark, empty shroud. ‘Yes, indeed …’

‘Then please tell him to bring it up.’ It sounded as if the revellers were ending their evening. Through the cracks in the boards there came from below much noisy scraping of stools, tramping of feet and unmistakable farewells. ‘I don’t want it carried off and lost to me.’

‘It’s secure, sir. Harold Pierce, the roadman, and William brought it in. It sits in the passage, safe enough for now.’

Two steps took her towards the door and past the bed. She glanced at the bundle and gave a gasp. ‘Oh, God save us!’ A pause. And then, ‘Is it dead?’

‘Yes.’ He didn’t look at it or her.

After a few moments, she was once more at his side. He ignored her and concentrated on the flames, although he was aware of her agitated presence.

‘Sir. Sir!’ Her voice was unsteady. As he continued to ignore her, she ventured to touch his sleeve. ‘It lives, sir! Its heart is beating. But it is very weak. It needs nourishment and …’

‘I gave it beer … but it will die.’ His voice, too, was dying.

She was impatient with him. ‘But while it breathes, surely … You cannot mean to let it die with no attempt to save it?’

It was those last five words that forced him to turn to her. He didn’t realise his tears were visible. He thought they were inside his head, as his grief was. Only, through his blurred eyes, he saw her expression alter from urgency to pity. And he could not speak. She said some words.

‘Do I have your permission …?’

The nod was hardly perceptible, but she saw it. First, she bundled out of the room like a whirlwind, leaving all behind. It was quiet now, below. Then came her voice and her husband’s. She sounding like a scold, he floating up angry and then conciliatory. Eventually, the great door banged and her footsteps were audible, tramping up the stairs and along to his room. She was breathing heavily as she entered, sounding as if she had just run a race.

She brought life and energy and urgency with her, but stopped it up as she reached his side, as if this was hallowed ground. He was twisted away from her in his chair, staring again at the fire, as if all he wished for were there.

‘May I … pick it up?’

He turned to her, then, and his voice came as a rising sob.

‘What use is there in that? It will still die …’ And without warning he collapsed against her, as a tree might fall against another in the wood, leaning his head against her ribs, clutching her skirts with fingers like twigs.

For a few seconds she was struck dumb, then she began to talk quietly in a soft, soothing voice.

‘It’s all right. It’ll come right, it will. So, calm yourself. And William is sorry but he caught just a glimpse when your cloak opened, and he thought it was a devil creature, God save us … hush now … an imp, like the paintings in the old church down the way, foolish man that he is … There’s one with a devil coming from a man’s belly, Lord bless us, and it frightened him so as a child, when he’d gone there for a dare … nightmares he’s had for many years, but he’s sorry …’ She kept her voice low and calm, paying no more attention to his sobs. Her words wove a little repair into his tattered mind, meaning being less important to him than her gentle tone. ‘If he’d known, he wouldn’t for the world … it was just … he wasn’t expecting … you a gentleman and all … he’d never imagined a gentleman with such a thing … and no woman to care for it. We knew you were bringing your wife once she had birthed … so did she die, then? I know it feels like the world has ended but all will come right in the end. Be still now. William’s gone … to ask the blacksmith’s wife if she’ll come down and see to it, so, you know all will be well. Her babe isn’t more than three months and she has plenty of milk … so don’t you fret … it’s all well now …’

She tried to move away then, but he only held on more tightly, his body shaking as he wept. She began hesitantly to touch his tangled hair and his back, stroking both gently and constantly, while all the time continuing her quiet talk. Slowly, his grip loosened as he became calmer. Now there were voices again in the room below, William and a woman, querulous, complaining, being hushed. Jane spoke again in the same calm, gentle voice. ‘That’s her now,’ she said. ‘She will do her best for it, put it to the breast, and she can stay here tonight if you wish it, stay close, keep it warm and safe, warm and safe …’

With that, she gave his hair a last caress and dared to put her arm around him, holding him reassuringly close. When she released him this time, he let her go. She went to the bed and picked up the motionless form of the infant, still talking to Christopher in the same way. ‘Now it’s wrapped in two shirts, I see … we’ll leave the one here. I told William to be sure Margaret brought an extra shawl, and I can make clouts. I have old linen here. I can use that for swaddling, and it’ll sleep with her in the bed and be warm that way.’

Christopher watched her through his hair and she showed she was aware of his gaze, bringing the bundle for him to see. When he showed signs of wanting to take it from her, she resisted, softly but firmly. ‘Now, they’ll be in the next room and not far at all. What you must do is pray for it, as we all shall, and then sleep, for it’s up to God now and Margaret to do her best … but its heart beats still, for all it’s so quiet. I’ll be back in a moment to make the fire safe and put you to bed, so don’t you fret.’

He was still in the chair when she returned without the infant. He made no protest when she knelt and removed his shoes and stockings. He stood like a child for her to remove his jacket and britches. She led him to the bed in his shirt, not asking if he had a nightshirt with him. Pulling back the covers, she helped him in and tucked him up. He turned away from her and lay on his side in the cold bed, while she attended to the fire and blew out the candle. Once she had left, he sat up and felt for the shirt he had used to swaddle the baby. Dragging it under the cover with him, he wrapped his arms around it and huddled with its scent to his face, waiting for sleep.

2

His dreams buffeted him as if he were standing on a steeply shelving beach facing an ocean of losses, all rolled into one unrelenting wave. It was as if he were attempting to wade while wearing his boots and heavy jacket. The grief sucked at his unconscious body, pulling him hopelessly under. It rolled him in its breakers and tossed him onto sliding shingle where he sought and failed to keep his feet. It soaked him through, filling him up with its cold misery until he leaked from his eyes, even in his sleep, bitter salt tears. If he could die, he would be at peace, but grief refused to consume him. His heart still pumped and his lungs still breathed, in spite of him drowning.

When Christopher woke he felt queasy, as if the sea still washed within him. At first, he did not know where he was. When he remembered, he discovered that having crawled exhausted into bed, he now found it impossible to rise. It was not that his legs were weak, but his resolve had quite left him. Far from this place being a new beginning, he felt it was the place where his life was about to end. He did not want to be told of the moment when his infant child ceased to breathe. He had already accepted that inevitability. Thinking of the babe made images of his dead wife caper horribly in his head. The yells of the blacksmith’s lusty infant made his loss the harder to bear and the only way he could gain some relief was to force his mind to recall incidences of his earlier life. And so, while the business of the inn carried on much as it had for close on two hundred years, its new owner lay upstairs, fighting to find a reason to live.

Cocooned in his nest, he thought of his long-dead mother. Her face was mostly remembered in a portrait that had hung in the great hall at home, a moated manor, slighted during the war, burnt and now little more than a heap of building stone. Her scent could be conjured, and the particular rustle of her dress. Christopher had a clear memory of sitting, splay-legged, hidden under her skirts, feeling entirely at peace. It must have been long before he was breeched. That important day he could clearly remember. The suit of adult clothes arriving from London, being dressed in them and proudly going to show his father. He remembered wearing the miniature sword, which his father had owned before him, on the occasion of his being dressed for the first time as a man. How he had cried when it became clear the next day that the sword was not his to play with, but only to be worn on special occasions. Injustice had burnt within him for a week, but then the freedom of breeches instead of tangling dresses was so delightful that the sword was soon forgotten, especially as play swords aplenty were to be had in the nearest hedgerow.

He slept a little more, to be woken by the girl, Sally, drawing the curtains. He could not bear the light and so she drew them over again, left meat and drink on his table and went to her other chores.

Urgency made him rise to use the pot. He drank a little but could not eat. Sliding once more into the warmth of his bed, he kept his mind on the past, frightened as he was for his sanity if he allowed the present to intrude. His father had provided him with both sword and pistol at the beginning of the war, before they buried the plate, his mother’s jewels and as much money as they could spare. Plate, jewels and most of the money had been found and taken by others. The remaining cache of coins he had was now mostly spent, and the pistol and sword he had thrown away on that dreadful day when Worcester was lost.

He had long since ceased thinking there was anything honourable about the act of fighting. It was a grunting, sweating, close quarters meeting of men he would prefer to argue with than kill. Had he killed? It was difficult to tell. He had caused wounds, yes, and had a line of puckered skin along one arm as his own evidence of engagement. How many of those wounds he had inflicted had proved fatal? The ball from his pistol that had lodged in that man’s face? He had gone down with a scream and had been trampled over in the narrow street by his own men. Everyone had been afraid of losing their footing on the slick cobbles of Worcester. Christopher remembered that. He remembered having, during the war, a prolonged and heightened state of fear, leavened by ennui while waiting to engage. During the rout, when he fled, along with others, hiding wherever they could, fear consumed him. He had got across the Channel, at last, for the price of a month’s hard graft harvesting turnips, as well as all the money he had. Once safe from the militia, in France, it took him some time to find out where he should go, with rumours of his king being killed, arrested, or in hiding. He had been just one of that ragtag of disheartened, traumatised young men in exile, trying to find their way to their nation.

Christopher turned onto his back and stared at the darkness. He had always tried to view his escape to France as lucky, even though it was a prelude to years of wandering the continent as a pauper. Should he thank God that he still had his head upon his neck or that he hadn’t been pressed into the New Model Army and sent to rot in Ireland? He didn’t pretend to understand the convoluted behaviour of God, striking one down, sparing another, allowing so much suffering of the godly, and innocent children. But that was dangerous ground.

It had been a lucky chance that had brought word to his ears that Charles had landed just down the coast from where he was attempting to keep his body and soul as one. Yes, he could admit that as luck. And so, too, the luck that had made raw the prince’s feet while in disguise, though not so very lucky for the prince. Lucky, though, that Christopher should arrive in time to offer Charles his own shoes, having – yes, by good fortune for them both – similar sized overlarge feet. And lucky that his height made him memorable. Such ridiculous serendipity made Christopher despair at the unevenness of life. But it had made him a junior member of this dishevelled court and, for a while, a friend of the king-in-waiting. It was not true friendship, not the friendship of equals – he had always known that – but Charles had been grateful and said so. Christopher even got his shoes back, once Charles’s mother had ordered her son a new pair made. In fact, Christopher had them still, much patched, or at least he thought he did … if he had stuffed them into his box, which had been brought up and lay untouched under the window.

He turned over again and looked at the dark shape of his box. He should get up, unpack a few necessaries and go down to take mastery of his realm. He willed his body up, but it refused. What was the use? Everything he loved had gone and he, a gentleman, had come now to this, owner of nothing but an ancient, slipshod building at the edge of a nondescript village that would oblige him to be in trade for the rest of his days. How had he got himself into this apology for a life? He could have taken himself to the newly restored court in London, asked for favour as one who had shared the King’s years of wandering. But those thoughts were taking him dangerously close to memories of meeting his wife and what came after. He shied away from that. He should get up, be a man, deflect himself from dismal thoughts. He did rise then and crossed the creaking boards to the window. He looked out onto the high road. Few people were about. It was another dry day, but no sun shone. He put his hand on his box but could not bring himself to unstrap it. He was too weary, too weary to live.

The next time he woke the day had gone and it was evening again. Light seeped up through gaps between the boards on his floor and he gazed at them, these shafts of light from a separate world. No doubt there was a good fire in the huge hearth and candles on the tables, as before. It was quiet though, nothing like the hubbub when he’d arrived. He wondered if the inn made as good a profit as Mr Gazely had assured him. The crowd busy drinking on the night he arrived had certainly given that impression, but tonight it sounded as if William was selling little ale. It had been quiet during the day too. Perhaps Jane had impressed upon each customer the importance of quiet as a form of respect for his circumstances or maybe this day of the week … and which it was he couldn’t recall … was usually quiet. It struck him that his Oxford education would be of little use to him now. How many of these people could read or write their native language, let alone Latin and Greek? There were several volumes of poetry in his box. With whom would he enjoy and discuss these pleasures now?

He looked away from the light in the cracks on the floor, and away from the meat and drink that he had not touched. Although he had slept for many hours he was still exhausted and slept again, yet his dreams as always were full of terror. When he woke once more it was still dark, but a thin sliver of grey light slid from the window where he had not completely closed the curtain. All at once, he felt he could not bear another minute on his back. Before his mind could object, he had lowered his feet to the floor and staggered up on legs that felt foolish with inaction. It was cold. He pulled the curtains wide to let as much dawn or dusk light in as possible. He could see that there was no fuel ready in the hearth. He lit a candle and stood it on the table to aid the examination of his box. He smelt rancid to himself, but there was no water in the bowl with which to wash. He dragged off his shirt and replaced it with the one he had used to swaddle the baby. Then he wrapped his cloak around himself and took a sip of the beer. In a moment he had drained the tankard. He had not realised he was so thirsty.

To prevent himself from seeking the warmth of his bed yet again, he began to walk to keep warm. It was only a few paces from the table to the door to the hearth, and hence to the window, but it did him good. Sharp grit from the floor bit into the soft places on his feet and made him feel more alive. As soon as he felt able to tackle his box, he knelt in front of it and undid the straps. It was packed full of a miscellany of possessions. The box had not been fully unpacked after the journey from Holland to Norfolk with his wife. The top layer was a jumbled mess of linen, books, a small box with his remaining money inside and his journal. There was also, to his relief, his second suit, much worn but serviceable enough. He took it out, along with some clean linen, and laid everything on the bed. It was getting lighter. Soon, surely, the servants would be up and he would command some hot water be brought and soap if they had it. Then, clean, refreshed and dressed, he would feel better able to make the journey downstairs. He wouldn’t allow himself to think any further than that.

3

It was the child, Sally, who came again, to take away yesterday’s food and ask if he wanted more. For a moment she didn’t notice him where he sat, wrapped in his cloak and coverlet and hunched in his chair. When she did, she stared at him before speaking.

‘Did you want me to lay the fire, sir?’

‘No. I want hot water in that bowl. And soap.’

‘The kitchen fire is not hot enough yet, sir.’

He looked at her. ‘Then, with as much haste as you can muster. I do not wish to wash in cold water.’

‘No, sir.’

The water when it eventually came was steaming. It gave his body pleasure, as did the donning of clean garments. He told himself that all would be well, as the anchorite Julian of Norwich had it, but she had believed in God’s goodness. He no longer trusted in God, or anything else. It seemed he could not even rely on himself. He must go down and confront the day, but the courage he had used to slash at his enemy’s head in battle did not seem to be of any great use against grief. It was not that he thought himself special. Many others had lived these past years with just as great or greater disasters than he had suffered. So why could he not be a man and face his life as it was? He had all his limbs and both his eyes. He had a roof of sorts over his head and servants to do his bidding. He had, he hoped, the means of putting food in his belly by mastering the trick of being the owner of an inn. William and Jane must know what they were about. He could manage servants. He could, he thought, inspire loyalty and so make them want to serve him well. He was not afraid of account books. But he was afraid of his heart. He was afraid that it was dying and, in so doing, taking his will for life away from him and replacing it with a will for self-destruction. In the face of that unholy desire, even a man such as he, with little faith remaining, feared hell.

A sudden shaft of early spring sunlight slanted into the room, making the grey ash in the hearth seem for a moment lit by pale yellow flame. The simple arrival of the sun transformed the room. In the dark it had seemed a place of refuge; now it looked to him tawdry, grimed and a mess. The bed was unmade, the floor was gritty underfoot and the table was strewn with crumbs, dust and a bowl of dirty water. Discarded clothes lay tumbled on the floor. As for the chair, it had held his shaking body as he disgraced himself by weeping into the skirts of a servant. It all shamed him, but if he could just bring himself to leave the room he could, surely, begin to find himself again.

The trick of it was to act, not to think. His legs had got him out of bed, his hands had washed and dressed him. Now his hand would open the door and guide his body along the corridor, down the stairs and into his world as it was today and would be henceforth. It faltered, that hand, but he willed it with all his strength, and he found that he was indeed walking along a corridor lined with dark panelling, pierced halfway along its length on one side by a window and on the other by two doors. He had no memory of walking it before, but once he stepped upon the stairs it was better. He recalled them, with their wayward slant. He trod them slowly, getting their feel beneath his feet and their sound into his head, while his hand slid easily down the bannister worn smooth by countless hands before him. Once down in the stone-flagged passage, he looked about him. To his left was a closed door and to his right one stood open, one he remembered. It led him into the room he had first entered from the road.

The room smelt of stale beer, woodsmoke and unwashed bodies – though none were in evidence. It looked abandoned. Sun was struggling in at the grimy windows, but where he was standing all was gloom and shadow. The great door was shut, the tables empty and several mugs stood about, as if their owners had left in a hurry. It struck Christopher that his first view of the inn, when he had met Mr Gazely and been impressed at the jolly nature of the place, had been mistaken. Then he had not noticed the grime. Now it offended him. How could he have thought to bring his wife and babe to such a place? The good oak settles had not been polished for years, perhaps never. How clean and ordered in comparison had been the home in Holland of his wife’s parents. After his years of homeless wandering, their comfortable and attractive home had soothed his heart. He had wanted to provide the same for his young family, but this was not it. No matter. He had no family. If this was what the village men demanded of their inn, then who was he to argue? But he could at least make sure his own quarters were kept sweet, swept and polished, and his linen washed. He left the room and went in search of his servants. Rather than call for them he would surprise them in their quarters. That was the way to discover how things really were.

Next on his right was the small parlour where he and Mr Gazely had conducted their business. When he opened the opposite door, he discovered steps leading down into a cellar. He closed that door and made his way along the passage, towards the kitchen. He stood for a moment in the doorway, taking in the scene. A small fire was burning in the hearth with a pot above it, and at the large table Jane was busy making pastry. Sally was scrubbing turnips in a bowl on the floor. It was a scene of quiet industry and Christopher was almost disappointed. There was nothing here to complain of and, besides, the smell of the broth bubbling away over the fire had given him a sudden appetite. Perhaps it was lack of direction, rather than laziness, that allowed the inn to be less cared for than it should be. As he was making up his mind to demand some broth, William came in from the outside door, carrying a basket of logs. He was the first to see Christopher and made haste to put down his load to better greet the master. Christopher didn’t miss the swift glances exchanged between his servants. It was natural for them to be discomfited at him arriving unannounced in their domain. He wanted to set down his rules for the household as speedily as possible, but his recent loss made him feel vulnerable. He needed to be liked. The compassion shown to him by Jane had shamed him, but her welcoming smile, dutiful but genuine, made him trust her and he found it easiest to speak first to her.

‘Are you making a pie, Jane?’

‘I am, sir.’

‘I look forward to tasting it.’

She looked embarrassed. ‘I can make another …’

‘She only means that the pie she is making is … ordered … for … a customer.’ William appeared as unhappy as his wife, but Sally, looking up from her scrubbing, showed no such trouble on her face.

‘He does like his pies, does Daniel Johnson. Best not cross him on that!’

Christopher smiled at her. ‘I would not wish a good customer to go without. By all means, Jane, make another. But while I am waiting I find I am very hungry. Would I be robbing this Mr Johnson if I had some of that broth?’

Jane went at once to the fire and ladled a little of the broth into a bowl. ‘I can bring it to you in the parlour, sir.’

‘But there is no fire in the parlour.’ Christopher found he preferred the company of his servants to his own. ‘I will have it here.’

He made to sit on a nearby stool, but William wouldn’t have it. ‘I will fetch you a chair from the parlour, sir.’

He bustled away down the passage and returned with a chair the twin of the one in Christopher’s room. He set it to one side of the hearth, close enough but not too close to the heat of the fire. Christopher sat, feeling somehow chastised, but the broth and a heel of bread soaked in it did as much good to the inside of his body as the wash and fresh clothing had done for the outside. He realised, as he enjoyed the fire, that this was the first time since he was a child that he’d had a proper home, and the first time ever he had one to call his own. The thought, and the knowledge that he had no one to share it with, sent a pricking behind his eyes that threatened to overwhelm him, so he shifted in his chair and set his empty bowl on the hearth. It was removed and replaced almost immediately with a mug of beer.

‘William?’

‘Yes, sir?’

‘I will need to speak to you about the running of the inn: the brewing of the beer, the purchase of spirits, the renting of rooms … I freely acknowledge I have much to learn. I intend to be fully involved with the inn and I have certain standards I wish to impose. This room seems clean enough, but as for the rest … they are not. I wish the furniture to be polished and the floors swept.’ He looked at Jane. ‘If you need to engage someone to help you then that must be done.’ She nodded. ‘But today I want my room cleaned properly, my linen washed as soon as may be and my suit brushed.’

‘We will all do our best for you, sir.’ She looked troubled and hesitant, as if speaking was painful. ‘Do you not wish to know about your son?’

He did not. And he did not want it called his son, as if it were a real dead person instead of an unbaptised corpse. Thinking of it brought his wife to his mind, and grief and guilt and horror. All of a sudden, he couldn’t breathe and his heart felt squeezed as if by an iron fist.

He got up abruptly. ‘I will inspect the brewhouse.’

He abandoned his beer and made his way to the kitchen door. Once outside, instead of crossing to the outbuilding, he made his way to an overgrown orchard at the back of the inn and took a deep breath of cold air. The memories came, unbidden.

She had been alone when he arrived back at the rented house. She was lying in their bed, quite dead, with the infant in her arms. He had thought it dead too. They both looked so peaceful there, her face white like ivory above his tiny features, but there was a smell of blood and death, pain and horror. He had paced about, upstairs and down, distraught, not knowing what to do, or, if knowing, not able. He remembered writing a note to the owner of the house, asking for his wife to be laid to rest and leaving money for it. He couldn’t remember how long he had spent there. He must have lingered overnight, but had he slept at all? He did remember going once more to the bed in the morning light. He had tried to pray for their souls as he looked again on those dead faces. And it had been then that the infant had moved.

He did not want it to live. It had killed his wife. More, he did not want to leave it there, to disturb her sleep. And perhaps, too, there had been jealousy. Why did it lie next to her heart, enfolded by her love, when he was now and for ever denied it? So, he took it from her cold arms, hardly knowing what he did.

What was she now other than flesh rotting? He could no longer believe in the mercy of God, or that they would meet again in paradise. And where did her body lie? He had paid for a coffin and prayers, but would the money have been used for that? He had abandoned her in life and he had abandoned her in death. He would never know where she lay. The babe should be with her, baptised and buried with its mother, not abandoned in some unhallowed, unmarked hole. He had done everything wrong and so now did not spare himself. His was all the blame. No. He did not want to hear of his son.

A thrush sang out of sight and a blackbird rummaged for the few remaining morsels of last year’s rotting fruit. A tiny blackened apple still hung upon the tree and, suddenly, the smell of earth and decay was too much to bear. Christopher abandoned the orchard and made his way past the side of the inn and onto the road, with no plan other than to escape his thoughts. To his left, the village ended. The road wound up a slight incline until it disappeared around a rocky outcrop in the distance, heading, he thought, for the coast. Golden gorse flowers lit up the verges. To his right, houses lined both sides of the road. It was fitting, surely, he thought, to discover a little about the village.

There were few people about. Most, he supposed, must be at work, either in the fields or at their various trades. A heap of withies lay ready for stripping. Chickens scratched and pigs grunted in the cottage gardens. In the middle distance he could see a mill on the river and beyond it some meadows. Nearby he could hear a smith ringing his efforts on the anvil. The church was small but with a fine tower. He hesitated there, wondering if he could bring himself to go in and pray for the souls of his wife and son, when a cart drawn by a sorrel mare came out of a side alley in front of him. He recognised the driver almost as soon as the driver recognised him.

‘Mr Morgan!’ The man halted the cart and looked down at Christopher. ‘Daniel Johnson. We met in your inn last night.’

He had the same easy smile he had worn in the inn, when advising Christopher about Mr Gazely’s departure.

‘You’re looking lost,’ he said. ‘Is our new captain adrift?’

‘No, I would not say that. I decided to walk out to see a little more of Dario.’

Daniel laughed. ‘It will not take you long, but why not climb up and let me show you what there is?’ He reached down his hand and Christopher took it. In a moment, he was sitting beside the man with the gold hoop in his ear, a person who was quite obviously not a gentleman but seemed a helpful sort. Christopher found himself engaged in much useful conversation as Daniel drove him briefly around the village and through the water meadow before depositing him back at the inn. He showed him the farm, which gave employment to most of the village, and the other inn, which he said was a poor apology for an ale house, and nothing compared to the Rumfustian.

‘You will have a good living here,’ he said, before Christopher got down. ‘I know because I supply your inn with good French brandy and wines, and many other things unobtainable in the village. I am just sorry that Mr Gazely saw fit to fleece you on his exit from the inn.’

Christopher looked at him in surprise. ‘What do you mean?’

Daniel smiled like a cat and the gold hoop in his ear flashed in the thin sunlight.

‘Only that having sold you the inn along with all its contents he proceeded to instruct William to give away all the drink after he had gone.’ He looked at Christopher as if to challenge him. ‘It is just as well that you arrived when you did, or all the alcohol you had paid for would have gone.’

Christopher frowned. ‘I suppose Jane brews regularly, but I will check with William to discover what else we need. Thank you for telling me. I … know I have a lot to learn.’

‘Rest easy, sir. Your servants are mostly honest sorts, and I will make sure you lack nothing for your business. There is a useful passage directly into your cellar, so you need not concern yourself with any inconvenience. What you need will be delivered there, I guarantee it. My family have been friends of the Rumfustian Inn for many years and I will make sure you have all the advice you might need.’

‘I am grateful,’ said Christopher, ‘to have you to advise me.’ The man was too forward and perhaps not altogether trustworthy, but Christopher knew he would need advice and he could not expect to get all he needed from servants. Daniel was certainly friendly, and Christopher was in need of friends. What was more, this Daniel Johnson was a distraction from the horrible drama that still played in his head.

His father would be appalled at how low his son had fallen, but the times were different. Christopher did not wish to be a courtier, even if he had felt that he would have been welcome at court. Nor did he want these people to call him ‘Sir Christopher’. It would be better to have friends than to insist on his correct title. His circumstances did not warrant it. This was where he had landed, and here is where he would stay. He would learn. And he would start now, with Daniel Johnson’s help.

He entered the inn with new-found energy, calling for William as if a storm was about to remove the thatch. William came running, his expression even more anxious than usual.

‘I mean to learn everything about this inn, William, and I mean you to tell me all I need to know. Where are the spirits kept? Is our supply depleted? What day does Jane brew? And I wish to see the account books.’

From despairing inertia to frantic action, Christopher filled the long day exploring his assets, demanding explanations from his servants and haranguing William for carrying out absent Mr Gazely’s last order, for all to drink freely without charge.

‘Mr Gazely was absent, sir, but Daniel Johnson was not!’

Christopher stared at his servant. William’s attempt to excuse himself angered him. ‘Mr Johnson was not your master, William. Once Mr Gazely had gone, I was, though absent. Any other man’s instructions meant nothing.’ Seeing William’s wretched expression, Christopher felt even more annoyed. Either the man was stupid or deliberately trying to appear so. ‘Daniel Johnson was pleased to tell me what good servants you and Jane are. Don’t repay his kindness by trying to make him responsible.’

Christopher saw various emotions pass like shadows over William’s face. Anger and injustice, swiftly followed by hopelessness as he subsided, as a servant must. Christopher was not much interested in what had passed before he had arrived. He was, in any case, unlikely to get to the truth. William didn’t seem the sort to volunteer information. He seemed, more than anything, cowed, but Christopher was fairly certain that he had not given the man a reason to fear him. Had Daniel? Well, if he had, it was in the past, now William’s new master had arrived.

There were more important things to consider. Christopher had lost the list of the inn’s possessions given to him by Gazely, so he created another. Turning his journal over, he dated the top of the last page and began. From room to room, he scribbled what it held, from feather pillows to leather chairs, gridirons to pewter ware. Firkins, bottles, hops, barley, cheese, flour – right down to the last broken stool in the cellar and the last egg in the kitchen.

In the evening, well pleased with his labours, he felt ready to meet his customers. Few men were drinking. Most of the tables were empty, but he was happy to see Daniel Johnson at the table by the fire, eating the food Jane apparently prepared for him every day. Christopher poured a little brandy into two of the English glasses the inn possessed and took them over. A day ago, he would have shrunk from conversation. Now, he was alight with the achievements of his day.

‘You were right about the lack of spirits and wines,’ he told Daniel. ‘I have been about my business all the day and am beginning to know it.’

Daniel paused in his chewing, smiled slightly and inclined his head in acknowledgement.

‘If you are still interested in supplying what I need I would be grateful for what is on this list.’ Christopher laid a piece of paper, torn from an account book, on the table and Daniel glanced at it.

‘I daresay you would be grateful to have these things sooner rather than later.’

Christopher nodded enthusiastically. ‘Indeed, I would!’

‘It will add a little to the cost for me to make a special trip to Chineborough, but I would be happy to oblige you. I can have most of what you want by tomorrow and will stow all in the cellar as I always do … if that would suit?’

‘I am most obliged, and much heartened by your kindness to me.’

Daniel pushed his empty platter away from him and picked up his glass. ‘I am always ready to help a friend.’ He raised his glass and Christopher did the same, surprised at feeling so cheerful. All that had gone before was dust and he would mourn the loss for ever, but he had a new home, new servants and now a new friend. Suddenly, life felt a little less empty.

4

The accounts, such as they were, itemised payments for the usual necessities but were less informative as to how the inn derived its income. Occasional lump sums did nothing to explain to Christopher if beer made more profit than food and if spirits indeed paid for themselves. Very infrequently, travellers had stayed overnight, and these events did appear in the accounts. Everything else was a mystery.

He could tell that both William and Jane viewed keeping records with dismay. William treated writing with great suspicion, or perhaps he was embarrassed at his lack of skill. Jane told her master that she was used to spending less than the kitchen and brewhouse earned, but Christopher was not to be deflected.

‘It is my will that you do this,’ he said to them both. ‘How can I balance my income and expenditure if I don’t know the facts of my situation?’

‘It is not just the inn that needs an accounting,’ said Jane.

‘What do you mean?’

She looked at him with the greatest amount of frustration that a servant might allow herself to show. ‘Why, there’s Mistress Smith given suck to your son and no hint of coin to recompense her.’

Christopher felt himself rightly rebuked. ‘I have been trying to keep the tragedy from my mind. She must of course be paid what is due to her. Perhaps you could ask her and settle up with her on my behalf.’

Jane was not satisfied. ‘But you must decide what is to be done, sir. Margaret was happy to help as a good Christian soul, but she wishes to know if you want her to keep the infant until he is weaned, or if you will engage a wet nurse for him from elsewhere.’

Christopher stared at her. A roaring filled his ears.

‘He lives, sir.’

It was like the roaring of a chimney fire, ready to burn down a house.

‘Sir? He lives, sir.’

It was a raging summer storm, lashing a full leafed wood.

‘I tried to tell you several times how he did, but you didn’t wish to hear it. He almost died that first night, but she says he is feeding well now, and gains strength every day.’

‘He lives?’

‘Yes, sir.’

Christopher stared blankly at her for a moment longer and then abruptly left the room. He felt nothing as he went upstairs and wrote two words in his journal. He lives. He looked at the words and, as their meaning rose from the page and up into his mind, he began to tremble. For a few moments longer he sat with his hand poised over the page, but he could think of no more words to write and, besides, his hand was shaking too much. Unable to sit still, he hurried back downstairs and out into the orchard. If he had a horse, he would ride until he was spent. He had to do something physical to quieten the churning in his stomach. He couldn’t think clearly. He couldn’t decide what he wanted to do or what he should do, so he took a billhook and began slashing at some of the brambles and nettles. When he eventually had to stop to catch his breath he had cut a swathe through the most tangled area. A bramble thorn had raked his cheek and he wiped at the trickle of blood with the back of his hand, smearing it down one side of his face.

He felt no better; in fact, he was even more agitated. He hated to know that the infant lived while his young wife had died. And yet he had pulled it from her dead arms. To save it? New doubts assailed him along with the old. Had she even been dead? Had he been too hasty in abandoning her? Where before he had known certainty, suddenly there were doubts. He was certain of nothing any more, except that he was losing his mind.

Christopher flung the billhook into the mess of tangled brambles. He tried to calm himself. His wife was dead. Her lack of breath, stiff limbs and cold skin had proved it. It was the living he must consider. Her infant lived, for the moment at least, and that changed everything. Why had he tried to save it if he had not wanted it? It was not the infant’s fault that his mother had died. Christopher remembered how his father had tried to comfort him when his mother had died of a fever, with him no more than a child. He had felt then that somehow he must be to blame. He had never spoken of it to anyone, but even now, at his most vulnerable, the childish thought was still there. Surely, he wouldn’t want the babe to suffer such useless guilt? His role now must be to put aside his own grief and be a comfort to his son. His son.

He called for Jane as he hurried back into the inn. ‘I will see my son now,’ he told her as they met in the kitchen. ‘Where is he?’

‘At the smithy, sir, where Margaret cares for him along with her own baby.’

‘Then send for her. No. I cannot wait. I know where the smithy is. And … I will take coin for her. You see, Jane. I do not forget my obligations.’

Every yard was too long and at the same time too short. His head was in turmoil. He should write to the infant’s grandparents in Holland. He had not yet written to tell them of their daughter’s death. Perhaps he should send the babe to them? But then he would not be a father to his son. He would engage a wet nurse and have her and the child at the inn. He would teach him to read and write, and would send him to Oxford to study, as he had done.

By the time he arrived at the smithy, his son was grown and betrothed, a dutiful son to his father and a comfort to his old age.

Christopher arrived breathlessly, with blood on his face and twigs in his hair, to find that his son had shrunk back to a helpless infant, lying in a box. As he bent over his son, a yellow blackthorn leaf dropped from his hair and landed on the covering. Christopher reached down to pick it up and the infant opened his bright black eyes. He had held this infant for many hours on the journey to the inn, but somehow it felt as if he was seeing him now for the first time. He had not thought it before, but the babe was so like his dead wife it made Christopher wince. It was too much to bear. He couldn’t do it. He would send him to his grandparents across the sea. But he could no more do that than strap feathers to his arms and fly. He was imprisoned by love, love of his wife that wouldn’t let him lose the only part of her that remained. There was his living son: a tiny Lazarus, a second chance.