Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Inkandescent

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

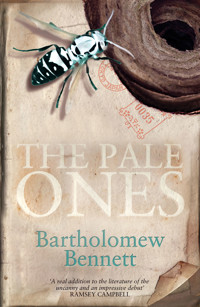

Pulped fiction just got a whole lot scarier Few books ever become loved. Most linger on undead, their sallow pages labyrinths of old, brittle stories and screeds of forgotten knowledge… And other things, besides: Paper-pale forms that rustle softly through their leaves. Ink-dark shapes swarming in shadow beneath faded type. And an invitation… Harris delights in collecting the unloved. He wonders if you'd care to donate. A small something for the odd, pale children no-one has seen. An old book, perchance? Neat is sweet; battered is better. Broken spine or torn binding, stained or scarred - ugly doesn't matter. Not a jot. And if you've left a little of yourself between the pages – a receipt or ticket, a mislaid letter, a scrawled note or number – that's just perfect. He might call on you again. Hangover Square meets Naked Lunch through the lens of a classic M. R. James ghost story. To hell and back again (and again) through Whitby, Scarborough and the Yorkshire Moors. Enjoy your Mobius-trip.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 147

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Title Page

The Pale Ones

Biography

Writer’s Note

Acknowledgements

Also from Inkandescent

Sign up to our mailing list to stay informed about future releases:

––––––––

MAILING LIST

––––––––

Follow us on Facebook:

––––––––

@InkandescentPublishing

––––––––

and on Twitter:

––––––––

@InkandescentUK

Biography

BARTHOLOMEW RICHARD EMENIKE BENNETT was born in Leicester, the middle son of an American father and English mother. He has studied and worked in the US and New Zealand, and has a First Class Honours degree in Literature from the University of East Anglia. Since graduation he has had various jobs: primarily software developer, but also tutor, nanny, data-entry clerk and call-centre rep, project manager and J-Badger (ask your dad), painter and decorator, and (very slightly) handy-man, working at locations all across the United Kingdom. He has also been known to dabble in online bookselling.

––––––––

The Pale Ones is his first published work, although he has been writing fiction continuously, long-form and short, since 2002. Currently he is at work on a novel about three children who experience a long, wintry December filled with gifts. Of the unusual variety. And trials. Of the trying variety.

––––––––

Currently he lives in southeast London, with his wife and two young children. He is a longstanding member of Leather Lane Writers Group, and since childhood, a dedicated reader of all manner of books, but especially tales of the “horror”. And in fact, some of the paper-packed rooms that feature in The Pale Ones bear a remarkable resemblance to locales in his own abode...

Praise for Bartholomew Bennett

––––––––

“An insidiously disquieting tale, flavourfully told. What begins as a dark comedy of book collecting gradually accumulates a profound sense of occult dread, which lingers long after the book is finished. It’s a real addition to the literature of the uncanny and an impressive debut for its uncompromising author.”

RAMSEY CAMPBELL,

author of the Brichester Mythos trilogy

“To a soundtrack of wasps, The Pale Ones unsettles in the way of a parable by some contemporary, edgeland Lovecraft, or another of the authors the used-book dealers in this story no doubt seek out, Arthur Machen. The unnerving images which flicker in a sagging English landscape of charity shops, seaside bed and breakfasts and amusement

arcades, washed with stale beer, linger in my imagination ages after reading.”

ANTHONY CARTWRIGHT,

author of Heartland, BBC Radio 4 Book at Bedtime

THE PALE ONES

––––––––

By Bartholomew Bennett

Inkandescent

––––––––

Published by Inkandescent, 2018

––––––––

Text Copyright © 2018 Bartholomew Bennett

––––––––

Bartholomew Bennett has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

––––––––

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

––––––––

While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher assumes no responsibilities for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the information contained herein.

––––––––

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

––––––––

ISBN 978-0-9955346-9-8 (Kindle ebook)

––––––––

www.inkandescent.co.uk

To the memory of Anne and Tina

Writer’s Note

About ten or fifteen years ago, it was entirely possible to make quick, easy money selling second-hand books through various online marketplaces – the best known being eBay and Amazon (although there were, and continue to be, other alternatives also). In the intervening ten years, the used book market online has changed substantially – commission rates have increased, postage charges have more than doubled, and changes to search algorithms and methods have in some instances narrowed the demand for certain, once-profitable older editions. And all the while, a tendency towards oversupply has steadily suppressed prices. Selling books thus is still absolutely a possibility, but the barriers to entry for the novice are much higher.

1

The second time I met Harris, he was rustling around the bookshelves of my local hospice shop. Whilst working my way along the parade of worn titles, I became aware of a greasy little smoke-like presence, a figure more dark wool overcoat than actual person, riffling through one of the boxes of sheet music in a brisk, cursory fashion suggestive of scant interest in the contents. I couldn’t pretend I wasn’t annoyed. The shop, cavern-like if not cavernous, was not ever busy and I was used to having the books, in their haphazard stacks and misaligned rows, to myself. The overcoat’s extreme proximity, and the way it backed into me without revealing its owner’s face, bordered on the uncomfortable, if not outright rude. I took a grudging sideways step, attempting to refocus on the grubby shelving and the broken, battered spines thereon. But some subliminal cue convinced me that I was being observed and so, annoyed by the sense of covetous eyes on the growing hoard of paperbacks in the crook of my arm, I made the error of taking a further – this time unguarded – glance at him.

And mistake indeed it proved to be.

I had read his body, or at the very least his posture, all wrong. He was facing me, poised and ready to seize his opportunity. It might have been a smile – or perhaps something else, small and dark and malicious – that rustled through the hair around his mouth.

— It’s that one you want, he said. — Nice little seller. Best unit you’ll find in this place. Best you’ll find along the high street.

He eased the hardback from the shelf. The tatty dust-jacket, its edges nicked and torn, bore the title in an archaic, angular font: World War II Destroyers. Below that the surname of the author, Jacobs, was just legible, its once-red lettering faded away to prosthesis pink.

— Fifty or sixty for that, maybe as much as seven-five if the wrapper there was in better shape. And after what they’ll ask for it in here...

He whistled quietly, and there again went the agile little rodent through his beard. From his hand movement I understood that by wrapper, he meant the dust jacket. He had an air of expertise; everything about him was persuasive, high-quality antique – from the dirty grey of his peppery, oiled hair to the papery, sun-worn skin around his eyes. His clothing conjured a distant suggestion of armour or carapace: wool and leather and silk, all top-end, perhaps even hand-tailored, and all lightly soiled. And his smell: a tight, high blend of cold, dead tobacco, mixed with something like turpentine, and old, desiccated sweat.

— I’d take it myself, but I’ve done all right this morning already. Got a vanload of academic texts from a house clearance job parked just up the hill: Routledge, Verso, OUP.

All tight and tidy... I like to help the younger generation; lambs haven’t much chance. Not the way it’s all going, handcart-wise...

I was unsure whether by ‘younger generation’ Harris was referring to me as an admittedly rather novice book dealer, or to the students upon whom he intended to unleash his stock of dog-eared academic disquisitions. But his having sized me up so assiduously felt something of an embarrassment: I imagined myself inconspicuous, the nature of my business in the shop opaque – simply a customer, perhaps a keen reader. In truth, the books I was searching out were units to be bought and sold; the internet had, at least for a while when all of this happened, made doing so a viable money-making operation.

— Go on, lad, Harris urged. — Someone’ll snap it up within the month. I gah-ran-tee it. For the plates alone, if nothing else... Take the blessed thing.

I didn’t want to; the shabbiness of the book didn’t appeal to me any more than did the odd little man pushing it forward. But I wasn’t gathering for my personal collection. And if I was making just a fifth of the profit he promised on every book I sold, well...

— There’ll be something another time you can do for me, he said.

For some reason, I found that reassuring. Perhaps because it felt familiar – something I’d heard before, or a deal I’d already struck. As I reached for the book though, I noticed with a twinge of revulsion that his middle finger had wrapped around it an old fabric plaster, its pinkness transmuted to the dirty grey of a putty rubber used to stipple charcoal. I thought that I could just make out the horrible green-brown of some ulcerated wound visible underneath the sticky, curled edge. I found it in myself to thank him for his advice, and turned back to my perusal of the shelves.

He refrained, thankfully, from offering any further tips, and after examining a few of the ancient browning pamphlets clogging up shelf space, wandered off to rummage through an immense wicker hamper crammed full of the shop’s perennial overstock of VHS cassettes – they had on a multibuy offer of the deviously illogical sort only ever seen in charity shops: twenty-five pence each, or twelve for a pound. Finally, before heading to the counter, I tucked the Destroyers book back onto the shelf. I’d spotted an unpleasant looking brownish stain along the bottom edge, and had decided it simply wasn’t worth the hassle.

Despite that, Harris had certainly been right about the asking prices: the shop was run on behalf of a local hospice, and was in a still grotty enough area of south London that they let their stock go for pennies. Hardbacks might command as much as a pound; that was if you could stop the old dears running the till from further discounting your purchase. They seemed absurdly grateful that you’d freed up more space for them to jam in a selection of their usual fodder: forgotten bestsellers, superseded study aids and newspaper giveaways. But for every fifty – perhaps even one hundred – items of dross there would be one book with actual resale value.

There was a hold-up while the customer before me, a stooped, elderly looking gent, the helix of his left ear partially eaten away by a sore the colour of a waterlogged raisin, tried unsuccessfully to negotiate an enlargement of the value of the sticky-looking fifty pence piece he proffered up in payment. Finally rebuffed, the man traipsed away, his intended purchase, a pathetically out-of-season snowglobe, left abandoned on the counter glass.

— Some people, blurted one of the women behind the till, no doubt intending the declaration to be overheard. — Do they not understand that we’re operating on behalf of charity?

She squinted distrustfully at me. — You get it, don’t you, young sir?

I gave her my best smile and nodded.

— Yes, she said, looking far from convinced. — I can see you do.

As it happened, I was used to a certain amount of dissimulation. I felt obliged always to grin and reassure the staffers that of course I’d enjoy my reading.

— It’s two-for-one on books, the second lady told me, after totting up the numbers. — You’re on an odd here. Did you want to find another?

Although this particular shop frequently did sell off their stock cheap, I hadn’t noticed any of the usual handwritten signs. And I knew this particular helper wasn’t one of the keener edges there. I paused, momentarily uncertain. Harris’s pick waited skewiff, spine reversed, along the top of a row of Mills & Boon.

— You might as well, said the first assistant.

She meant, I judged, quite the opposite. And that, for me, settled it.

The tactic, as far as I could tell, was to pair the borderline senile with the partially-sighted, in the vague and generally unfulfilled hope that each would compensate for the other’s inadequacy, rather than multiply one another’s errors. That day they managed a modest accuracy: despite having convinced me to take away more of their stock, they still contrived to undercharge me by a pound or so. To compound my sense of guilt, I noticed as they tallied up that they’d miscounted originally – I’d had twelve in the first place. With the scant time remaining to them on the earthly plane, it seemed unfair to ask for the waste of a further fortnight in rerunning their glacial calculation. I’d seen enough of the more belligerent of the two to know she’d take offence at my correcting their joint reckonings, so instead I merely stuffed my change into their desktop collection jar.

The simpler of the two volunteers smiled at me.

— Bless you.

The other peered with something like revulsion at the blue plastic chalice, as though I’d seen fit to defecate into the Holy Grail itself.

— Another one, I heard her say as I made my way to the door, her late December voice breeding resignedness with disapproval.

The other volunteer tried to shush her. It served only to put an edge on her counterpart’s tongue:

— Oh yes. A knight, that one. A regular Roland.

I paid her little mind, busily wagering myself that the copy of Drummond and Manning’s Bad Wisdom (the Penguin edition, a cultish favourite, bore a gilt spine and cover, as if in happy recognition of its worth as a used book) that I’d found would trump Harris’s tip, both in terms of price and speed of sale. Some low, unbridled part of me thrilled to the thought of comparing dividends.

Outside, I decided that I’d done more than enough to have earned my mid-morning coffee and so eased a couple doors up to a newly-opened coffee shop – its pre-distressed furnishing and outrageous prices at that time something of a departure for the area.

It was as I stood waiting to order that Harris materialised at my shoulder. I’d taken the book I was reading out of my bag in anticipation of having to dump everything else I was carrying at the counter: a gathering of blinking, squinty-eyed new mothers, their accompanying infants in strollers, had dammed up access to the few remaining free tables.

— Surely you’re not going to refuse me a cup of black? Not after the wedge I just slipped into your trouser pocket.

I motioned at the chalkboard menu.

— Whatever you want.

— Or...

He left that hanging there long enough that I felt obliged to look over at him with expectant eyebrows.

— ... you could just give me that Lowry there.

Under the Volcano was the book I had in hand. A ten-year-old Picador reprinting worth, I was quite certain, absolutely nothing. My attempt to read it had stalled early in the New Year, around the time Karen left for Japan. Reading about a hopeless drunk hadn’t seemed like much of a transport then. But I didn’t ever like to give up on a book, and I’d retrieved it just that morning from the bottom of my bedside stack, my initial foray still bookmarked about a fifth of the way in. I hesitated, primarily because I’d have to find something else to read while I drank my coffee. But then, quite reflexively, I opened the book. The object marking my place was a strip of old-school passport photos: Karen and I stuffed together into the booth, gurns growing more grotesque with each shot.

— Sorry, I told Harris, — I need to keep hold of this.

I knew there was a streak of irrationality to my decision – it would be trivial enough to find another copy of the book. But somehow letting it go would have felt too much of a betrayal. He looked disgruntled at my refusal, his eyes still fixed on the photographs.

Harris made some dismissive, not wholly cogent comment then about broken spines and the disappointment of imperfection. I glanced down, annoyed. I took great care always not to crease bindings. I treasured all my books. Even the beach reads.

— But it’s perfect, I told him.

— Of course it is, he said, his voice low and mean. — Everything’s just perfect.

I tucked the book away under my arm. But Harris hadn’t finished.

— I could force your hand, you know.

I didn’t know what that meant – what the hell that meant. But it wouldn’t do, losing my temper. I wasn’t, I reminded myself, to do that any more. I’d made a decision – and it held, whatever the reason for my anger. He was waiting, his face expectant, and I felt a sudden, lucid conviction that he knew already the suggestion I was ready to make: that he might mount the tailpipe of his book-loaded van.

— How about that coffee? I asked instead, not quite able to inject the right amount of goodwill into my offer.

— No, no. He smiled. — Got to go and make money.

And then, clapping me on the shoulder hard enough to spill the drink I had just lifted from the counter, he was away again. It was funny because Harris had appeared initially, I was quite certain, at my right, meaning he had to have somehow ghosted his way out of the seating area and through the crowd of mothers. But I had been sure that he had still been in the hospice shop when I left, sizing up their selection of flat caps. Glancing out into the morning sunlight I caught sight of him across the road, slipping through the gauntlet of broken, dowdy smokers clustered about the even dowdier entrance to the Railway Tavern.

He wouldn’t be making any money in there I thought – rather archly – to myself. But then I noticed he had stopped to speak with one of the men outside: a stoop-shouldered gentleman, familiar in his frailty.

Harris lifted something from his pocket.

Sunshine winked from a clear sphere: the ornamental snowglobe. Harris pressed it into the man’s hand before disappearing into the gloom.

2

The dream I had after that encounter was a simple one.

There was a circular ashtray, its rim covered with a great fan of long white cigarettes. I pulled the cigarette that belonged to me to my lips, where I discovered that it wasn’t a cigarette at all but the bone, denuded of all flesh, of my middle finger. I drew on it nonetheless – through my thumb, as though that digit were somehow a pipe stem, as in the logic of dreams. It was then I discovered – wrong again! – that the bone of my finger was not bone but a roll of hollow, empty paper, quickly consumed by the red smouldering ring of the lit tip.