Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

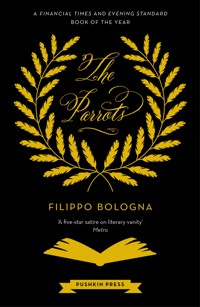

A searing satire of the literary world, in which three men fight - to the death? - for a coveted literary prize Three men are preparing to do battle. Their goal is a prestigious literary prize. And each man will do anything to win it. For the young Beginner, loved by critics more than readers, it means fame. For The Master, old, exhausted, preoccupied with his prostate, it means money. And for The Writer-successful, vain and in his prime-it is a matter of life and death. As the rivals lie, cheat and plot their way to victory, their paths crossing with ex-wives, angry girlfriends, preening publishers and a strange black parrot, the day of the Prize Ceremony takes on a far darker significance than they could have imagined. Filippo Bologna was born in Tuscany in 1978. He lives in Rome where he works as a writer and screenwriter. His novels The Parrots and How I Lost the War are also published by Pushkin Press. "With Filippo Bologna's mastery of language, the results are brilliant and amusement is guaranteed." La Repubblica "A flaying parody of the literary world and its vanities." Il Giornale

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 378

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

FILIPPO BOLOGNA

THE PARROTS

Translated from the Italian by Howard Curtis

CONTENTS

THE PARROTS

He saw all kinds of birds, among them one that had no arse.

Antonio PigafettaReport on the First Voyage around the World

For Arianna, who flies higher

PART ONE

(Three months to The Ceremony)

IF ONLY MEN looked up at the sky, they would see different things. Not the things they usually see: the blackened asphalt, the yellow leaves, the puddles, the dogshit, the used chewing gum, the unmatched earrings, the coins that only the luckiest can spot.

No, they would see different things.

They would see the cockpits of planes glittering in the sun, clouds frolicking like dolphins in love, treetops swaying in the wind, the sky changing colour, the horizon curving with the turning of the seasons, they would see the first star of the evening and the last of the morning, the lights going on and off on the top floors of the apartment buildings, they would see flower-filled terraces, roofs bristling with antennae, sheets hung out to dry on washing lines.

They would also see a young man standing in pants and T-shirt on the terrace of a small loft on the top floor of a Fascist-era apartment building that had once been working class and was now much coveted by property companies.

He is leaning on the handrail of the terrace and looking down, towards the still-illuminated signs of the petrol stations and the scooters stalking the overcrowded morning buses. If he looked up instead of down, the young man would see a dark unidentified object slowly but inexorably approaching.

Behind him, beyond the large glass door wide open on the dawn, her long black hair spread over the white pillow, his girlfriend is lying asleep on a small, uncomfortable but hypoallergenic double mattress, and inside his girlfriend, someone else is asleep—as it’s early days yet, it might be better to say “something” rather than “someone”—something is asleep, something the young man doesn’t yet know but will get to know in three months’ time.

Hard to say why he’s woken up so early: maybe a bad dream, or maybe he’s just feeling nervous because it’s not long now till The Prize Ceremony.

Don’t be deceived by the fact that he’s in his pants and T-shirt on a terrace in Rome on this bright spring day. The young man is a writer, a writer at the beginning of his career, so he won’t be offended if we call him The Beginner (it’s what everyone calls him anyway). That’s what he is, because he’s written and published just one novel, but one that hit the bullseye. You don’t actually have to have read it to know that it’s one of those books that will last, one of those once-in-a-lifetime novels, the work of a young man who already seems mature, as the critics have been at pains to point out.

On the other side of the city, almost in open country, some twenty kilometres as the crow flies from the terrace on which we have just left The Beginner, in the house of the caretaker of Prince—’s estate, a full bladder drew the attention of the owner of the body in which it was imprisoned. This owner was a thin, white-haired man who loved—indeed, insisted on—being called The Master, and as we have no objection, that is what we shall call him.

The Master grunted beneath the blankets and groped on the bedside table for the lamp switch. This clumsy gesture only succeeded in causing a tottering pile of books on a little table to fall. The Master finally managed to locate the switch, but the lamp did not come on: the fuse had blown again. One time it had been the alarm clock, another time the hairdryer, another time the electric shaver… When he won The Prize, he would have those dammed kilowatts per hour increased from two to at least six. In fact, if the book did as well as he said it would, with the advance on the next one he would even ask to be connected to the industrial three-phase. And then tumble-driers, air-conditioners, record players, cassette decks, television sets, video recorders, refrigerators, washing machines and dishwashers would all start together, simultaneously, like the elements in a mighty orchestra of domestic appliances playing the last movement of a symphony. But at the moment, with the tiny advance granted by The Small Publisher who brought out his books, all that was as remote as it was unlikely.

What’s more, if they had The Master’s CAT scan on their desks, no publisher would ever give him a single euro as an advance, regardless of the quality of the book. But all in good time. The priority now is to let a bit of light into the room and allow The Master to pee, because he can’t hold it in much longer.

The Master threw his tired legs over the edge of the bed and searched under the bed with his foot, but succeeded only in shifting a few balls of dust. He was looking for his flannel slippers, which always got stuck in the most absurd places, as if they took advantage of the night to walk home, calmly doing without his feet. Unable to find his slippers, The Master placed his cold feet on the floor. He grabbed a dark heap lying on the armchair that had been pushed up against the bed in the hope that it was his dressing gown (it was), put it on (inside out) and stood up. That was what the second of the three finalists for The Prize did.

“Damn and blast!” We can assume that this was the oath uttered by The Master who, in his clumsy move to the arched window, had knocked over the chessboard precariously balanced on the desk.

The Master threw open the blinds and a weak light penetrated his den. That’s a bit better now, he thought.

In a manner of speaking. The morning light was dim but there was enough of it for him to contemplate the mess: the chessboard on the floor, the pieces scattered around the room. To the not easily quantifiable intellectual damage—very difficult, if not impossible, to remember the positions in that thrilling endgame—had to be added other possible damage, the alabaster pieces being quite hazardous to his bare feet. The Master’s oath was not entirely ascribable to the disaster of the chess pieces. It was also and above all related to the stab of pain at the level of the perineum which this movement had caused him: even though they had taken out the stitches more than a month ago and the scar was now completely healed, it still hurt.

As he went back towards the bed, tacking amid the disorder of his room, The Master tried as best he could to co-ordinate his movements in order to cross a space as yet barely illuminated by the first light of day: crumpled clothes on the armchair, books covering every surface and creating unsafe architectural structures, overflowing ashtrays balanced on the shelves of the bookcase, a pair of chipped Chinese vases, a portrait resting on the floor with the frame gilded and the content so dark and greasy as to make the subject impossible to distinguish, the small electric heater with only one bar working, and the (constantly slow) wall clock marking six something… Wherever he turned his gaze, The Master found something that reminded him that his life up until now—and it was already quite a long life—had not gone as he had expected. Although he was now of an age when he could no longer even remember how he had expected it to go, which actually made him feel him a little better. What he did know was that his discontent encompassed more or less everything. It needs to be said in all honesty: The Master was really disappointed by life. But given what was to happen later, life could have said the same of him.

In the meantime, The Master headed for the bathroom to satisfy the urge that had roused him from his bed, and all at once realized, or recalled—at The Master’s age they amounted to pretty much the same thing—that the flushing of the toilet the day before had let him down. He looked disconsolately at the chain hanging uselessly like a bell pull for calling the servants in a house belonging to aristocrats who have been guillotined. He had vowed to call a plumber the next day, which unbeknownst to him had already become today, but in the meantime he needed to find a solution. And fast.

He thought of doing it in the bidet or the sink, then had qualms and told himself that these weren’t things a Master did. Fortunately he now saw his slippers, his old flannel slippers as nibbled as a donkey’s ears, in a corner of the bathroom, next to the shower, and put them on. Then he pulled his dressing gown around him and went out into the cool of the morning.

Prince—’s estate was bathed in a cold, transparent light. Tall grass besieged the pigeon house: the base for his squadron of homing pigeons—now decimated by illness and by a beech marten that had found a hole in the wire netting—which needed a good clean inside and a coat of paint outside. But not today: afterwards, afterwards.

After The Prize. After the victory. After the glory. When it was all over. Then, a bit of manual work would actually be… relaxing, thought The Master.

He lowered the slack elastic of his pyjamas and at last, in the meadow damp with dew, at the foot of a centuries-old pine, in the bright morning of what had once been open country in Lazio and was now a green island surrounded by concrete, he gave himself up to the sweet relief of urination. The operation lasted an indeterminate length of time, but long enough for The Master to become intoxicated with the alcoholic scent of resin, to feel the morning breeze caress his face sandpapered with beard, and to contemplate the majesty of the age-old pines and oaks that populated Prince—’s estate. Those trees, shrouded in morning birdsong and hidden by the dawn mist, seemed to him magnificent. One in particular filled him with pride, the one he had chosen as the target of his foaming jet. Being a man of letters and not of the jungle, The Master was not to know, first of all that the pine was a cedar, a Lebanese cedar to be precise, and that, to the detriment of its power, it was sick and would soon collapse onto the roof causing considerable damage to the house of the caretaker of Prince—’s estate.

Millions of greenflies, little parasites as big as lice behind the rough bark, were patiently emptying the trunk from inside, reducing it to a sickening mush not unlike sawdust.

By a cruel, subterranean analogy, the same thing was happening in The Master’s exhausted body, inside which millions of tumorous cells lurking tenaciously in the prostate—removed, though belatedly—were proliferating in his organism, joining forces in metastases that would soon attack his old bones and reduce them like the cedar on which he was peeing, although rather more quickly.

In any case, that was of no concern to him right now, because the fall of the cedar would happen well after the end of this novel, and unfortunately, well after the end of The Master himself. And this in spite of the encouraging opinion which a well-known urologist would soon be expressing during his check-up—marked down, in his secretary’s diary, for that very morning.

Elsewhere, while The Beginner was sweeping the terrace of what remained of his glass door (an event closely related to the dark unidentified object approaching slowly but inexorably) and The Master, unaware that he was entitled to an over-70s card allowing him to travel free on public transport, was punching his ticket on a bus heading to the central area where the well-known urologist had his clinic, a beautiful young woman closed behind her the door of a house in a residential neighbourhood.

Ever since the young woman, who had recently become The Second Wife in front of witnesses and a minister of the Lord after the annulment of The First Marriage by a church tribunal, had resumed work after her pregnancy, that precise moment—ratified by the liberating slam of the reinforced door, the click of heels on the gravel drive and the hum of the twin-cylinder engine of the Fiat 500 as it started up—represented for the man universally referred to in the captions to his photographs as The Writer the most beautiful moment of the day.

Most beautiful because The Writer, the third and last finalist for The Prize, could only write in the morning. Not, however, before observing a whole series of what could be seen either as procedures or as rituals, depending on whether they were viewed from a secular or a religious standpoint.

First of all, then, The Writer went into the bathroom, evacuated his intestines with great satisfaction, then showered and shaved, as he did every day, in order to remain close to an ideal (a fragile one) of (his own) youth. Still in his bathrobe, he went to the big bedroom windows, drew back the curtains and looked out. A radiant spring morning in Rome. The clear sky, the newly pruned hedge—although here and there troublesome clumps broke its evenness—the sonorous noise of tennis balls that reached him as if from the far end of the neighbourhood—who on earth was winning? The Writer sighed, closed the window and drew the curtains in order not to fall into temptation.

After which he got dressed in the kitchen left untouched by The Filipino (who at the moment was not here), emptied into the sink the lukewarm coffee that The Second Wife had left for him with instructions to heat it in the microwave, and prepared a prodigious pot of coffee with all the meticulousness of a bomb disposal expert defusing a device. As he waited for the coffee to rise with a gurgle, The Writer looked through the sheaf of newspapers The Filipino had placed on the kitchen table before disappearing (what on earth had become of him?).

To say that he read them would be an exaggeration. What he did was leaf through them. An oblique, distracted, summary glance at the headlines, then straight to the sports page, and only then to the arts page. He checked if any colleague or journalist had written anything about him or about his latest book, the one which was up for The Prize—they had—and thought about whether he should let it go or reply, thus contravening the first principle that had made him a beloved, successful writer: Never respond. To anybody. Whatever they said. Because the only sure way to hurt a person isn’t to talk ill of them (what naïvety!) but not to talk about them at all. If you don’t talk about something, it means it never happened. Silence equals death.

From a jug, The Writer poured himself a little orange juice, already oxidized, took a bite of the now cold toast The Filipino had prepared for him (he ought to be dismissed without mercy) and looked at the page, forcing himself to be as detached as possible. In the dead centre of an imaginary triptych which he formed with the other two, there was an old photograph of him, with the copyright of a well-known agency. There he was, near the bottom of the page, younger and bolder than he was now, equipped with an invincible smile, worn jeans and creased shirt, challenging the photographers against the background of a dazzling park: “Well? Is that all you want to know?” he seemed to be saying to the ravenous lenses of the digital cameras. Beneath it, a caption: Forty-six years old, Writer. His photograph was mounted between the two others, in a forced iconic cohabitation, which gave him an unpleasant feeling, the kind of discomfort we feel when we are hemmed in by a crowd. The other two photographs captured an old man with unkempt hair and a mean-looking face, and a young man with a ridiculous goatee and an expression of impunity (or was it stupidity?) typical of youth. Even though he knew both of them, the sight of those faces made him nauseous.

That was why The Writer immediately went on to read the article. The author of the piece commented on the “trio”—as the shortlist of finalists was known in the profession—vaguely summarized the three books in contention, and finally speculated wildly on the likely winner of The Prize. The commentator considered the old man, whom in a couple of passages he also called “The Master” (though not without a streak of irony, thought The Writer), to be out of the running, and The Writer to be the favourite. The Writer instinctively put a hand just under the belt of his bathrobe, and took another bite of his cold toast. Like a condor (Vultur gryphus) circling over a plateau in search of a moving prey, The Writer skimmed over the rest of the piece, which was just idle chatter, and went straight for the prey, the last sentence, extracting from it a juicy morsel: “Even though victory seems within reach, the game is far from over: to win The Prize, The Writer will have to watch out for The Beginner…”

But if The Writer had to watch out for The Beginner, who did The Beginner have to watch out for? That was something the newspaper did not say.

And yet on the terrace of his loft, The Beginner would have had convincing reasons to watch out. Starting with that dark object approaching, an object The Beginner could not see because he was looking down, or at best in front of him.

As he was staring at the digger on the subway construction site, motionless in the brown morning air, his mind was elsewhere. He was thinking about The Prize, about what he would say at the event due to be held in a famous theatre that afternoon, and about other small details, the result of his insecurity and his incurable desire to please. Nevertheless, beyond the galaxy of The Prize, there was something on the ground that captured his attention.

On the crane on the building site, towering over the digger, there sat a large flock of seagulls (Larus michahellis), rubbing their wings, creasing their feathers and jamming their gullets between their tail feathers. The Beginner had re-emerged from his thoughts and was now watching them, his curiosity aroused: they seemed to have fallen in line, as if waiting to swear an oath. There must be some kind of logic in their arrangement, but what was it? The biggest and strongest had secured the best places along the arm of the crane, the most sheltered places and the closest to the tower. Those on the end of the arm, on the other hand, the most exposed to the wind, were trying to regain ground, to move up the line, only to be forced back with a lot of pecking as soon as the attempt became more insistent. Until, exasperated and phlegmatic, they would launch themselves into the air, circling around the crane, and after one complete turn find that their places were gone, having been immediately occupied by other seagulls. And so they hung suspended in the air, beating their wings against an imaginary mirror, before again roosting in the few free centimetres at the extremity of the arm. And this merry-go-round went on uninterruptedly, like an impossible quadrille in which the dancers step on each other’s feet because the platform is too narrow.

All at once, a shudder ran down the line of seagulls, spreading along the crane’s metallic conductor. Their feathers stood upright, their wings opened and the line broke. The seagulls rose in flight and circled the arm, unsure whether to come to rest or leave. Then they flew away, scattering nervously, as if something had disturbed them.

The Beginner felt a shudder at his back. Maybe it’s the brisk air of the morning on my bare neck, he thought. Maybe I shouldn’t go out on the terrace in my pants, he thought. Maybe I’m getting a fever, he thought.

But no, it was none of these things. It was as if he felt himself being watched by the menacing eyes of a stranger. He sensed a looming presence, the atavistic but indemonstrable certainty that he was not alone on that terrace. A sensation which lately he had already felt at least once.

He inspected the terrace: the rack of dormant jasmine, the stone vases in which lizards took shelter on hot summer nights, the rubber hose coiled in a corner. A slow pan of the buildings surrounding the terrace offered nothing better: closed windows, lowered blinds.

He leant over the railing: the small, faded pedestrian crossing beneath the pines, the pines themselves climbing vertiginously, their tops challenging the roofs of the buildings, not a single passer-by in that measly stretch of street, only a Carabinieri car returning in resignation from a night patrol.

Even though the sensation had become even more distinct and intolerable, The Beginner did not yield to the instinct to turn: there wasn’t anybody on the terrace because there couldn’t be anybody. So he decided to go back inside.

The question is: as he closed behind him the massive glass door that slid obediently to the end of the runner, and especially as he drew the heavy curtain to stop the light from flooding the room so early, could The Beginner imagine the fearful crash which, in a fraction of a second, would shatter the window into a thousand pieces? No, he couldn’t. You can bet on it.

With the house at last empty and silent, The Second Wife trapped in the Fiat 500 as she drove alongside the river, The Baby fast asleep in her room and The Ukrainian Nanny ironing in the linen cupboard beside the screen of the baby monitor so firmly imposed by The Second Wife and equally firmly challenged by him (only two months old and already on video—how can we complain if they end up on Big Brother?), The Writer only had one thing left to do. Something shameful, unforgivable and irrevocable: to write.

The Writer sat down on the ergonomic stool The Second Wife had given him for his birthday (sceptical at first, he had had to think again: it did wonders for his backache), switched on the computer, waited for the smiling face of a baby, which he had chosen as a screensaver, to appear, looked for a particular file with the suffix .doc to which every additional word added a nerve-wracking amount of time waiting for the word processor to launch, and double-clicked on it. During that interminable moment it took the application to load the file, so slowly as to make him regret having opened it, the telephone rang at the far end of the living room.

Someone answer it, thought The Writer. Damn, just when the file had opened and he had glimpsed—maybe—a clause to be moved to the next paragraph.

“Someone answer it!” This time the words, which he had previously only thought, emerged from his mouth. But the telephone kept ringing, and nobody had responded to its call.

Anyway, seeing that The Filipino wasn’t there and that not even the author of a novel can guarantee that every character will be available at all times, and given that nobody in the whole house was lifting a finger to answer the telephone, which was still ringing, The Writer had no choice but to get up from his desk.

A pity, just when the sentence was on the verge of coming together, first in his brain and a moment later on the keyboard. The telephone rang again, and The Writer approached it. Against the light, the corridor was shiny with wax polish, the surface of the floor looking like asphalt after a nocturnal shower. The telephone rang, and The Writer walked, without speeding up or slowing down, taking care not to slip on the polished floor, as a painful domestic experience had taught him. The telephone rang, and The Writer reached it. The telephone rang, and The Writer lifted the receiver.

“Hello?”

“It’s me.”

There was only one person in the world who could call and say “it’s me” without being The Second Wife. Let alone The First.

“This is your prostate.”

“What is?”

To hear this line, you would have to be in the centre of Rome, in the prestigious clinic of an even more prestigious Roman urologist. The Master had answered mechanically. His attention had come to rest on a poster hanging on the wall, just behind The Urologist’s armchair.

He couldn’t take his eyes off the image, which was surrounded by a plethora of diplomas and testimonials to victorious campaigns around the world. Where had he seen that painting?

“This.”

The Urologist pointed with the tip of his pen to a darker area floating in the grey sea of the scan. A kind of lunar crater shaped like a chestnut, a pyramid built on the moon by an alien civilization and recorded by a space probe: his prostate as shown by the ultrasound.

Those eyes, once bright and now watery, had become small and sharp over time after perusing thousands of close-packed lines in cheap editions in the gloom of furnished rooms, but still managed to establish a familiarity with that picture.

It was a reproduction of a painting. At the bottom there was a small semicircular bay, a cove imprisoned between an inlet and a bare, twisted tree. In the centre, a man standing on a rock, his trunk tilted forward, leaning towards the water. Behind him, an elemental horizon and a flake-white sky. From every part of the picture, hundreds of creatures, fish, birds, reptiles, were converging on him, like lines towards the vanishing point in a study on Renaissance perspective. Turtles, crabs, lobsters, a seal or a sea lion—The Master couldn’t tell which—even a shark and a hippopotamus, as well as seaweed and plants, all seemed attracted by the man’s magnetic force. The animals had come from the depths of the sea, the expanses of land above sea level and the boundless skies to hear his words.

“And this dark patch…”

In the Wien Museum in Karlsplatz. That was where he had seen it. Vogelpredigtdes Hl. Franziskus: in his mind that caption echoed like the chorus of a song. As a young man, The Master had studied German for a while, not enough to master the might of Germanic philosophy as he had hoped, but sufficient to remember the name of that little painting.

“…is the tumour.”

“But didn’t you take it out?”

“Of course we took it out. Why else would we have done the operation?”

The Urologist laughed, The Master didn’t.

“This is the image of the prostate we removed, and this is the area affected by the carcinoma, do you see?”

The Master could not see. The professor traced a kind of half-moon, making a mark with the cap of the biro on the surface of the image. “In your case a radical prostatectomy was the only solution. The result of the biopsy on the lymph node was negative, which means the tumour probably wasn’t invasive. In any case, I’m convinced we caught it in time!”

In time, maybe. But we need to see where we caught it, thought The Master.

“The picture seems reassuring.”

“Which picture?”

“What do you mean, which picture? The clinical picture, what else?”

The one The Master was looking at, that was what else. The Master abandoned his prostate, sunk there in the murky backdrop of the scan, and took shelter again in the intense contemplation of that image.

It was a painting by Oskar Laske, a pupil of Otto Wagner, StFrancis Preaching to the Birds. How envious he felt. Not so much of the painter, who wasn’t even all that gifted—too graphic for his taste—but of the saint.

The Master would have liked to read his poems and stories to men and animals, and have them listen admiringly, docile and grateful. Basically, St Francis’s sermons were readings ante litteram. The birds were the readers, and the wolves the critics. And the cruel wolf of Gubbio that St Francis had single-handedly tamed and made as playful and tail-wagging as a puppy was that critic (the only one) who spoke well of him only because every time one of his books came out The Master wrote to him expressing respect and admiration for his latest literary effort.

“Anyway, look, a cancer of the prostate at your age isn’t a rare occurrence, you’re not the first and you won’t be the last, and there’s very effective chemotherapy now which is less stressful for the organism…”

Hypnotized by the painting, The Master felt as if the spaceship of his youth were abducting him in a cone of light and carrying him back in time.

Now the spaceship had taken him to Vienna, a crash landing in the Resselpark, the prostate still in its place, ready to produce all the quantity of seminal liquid that the hypothalamus had requested, with a raging snowstorm beating down on the city, and on his young shoulders.

The snowflakes were whirling about him with such fury that he had felt as if he were being attacked by a swarm of frozen wasps. Floundering in the storm, he had headed straight for the massive building at the far end of the park. Beyond the curtain of snow a light could be glimpsed inside the building. Without knowing what the building was, he had pushed open the door and gone in.

Wooden floors and warmth. Light and silence. A refuge for wayfarers sheltering from the cold? More than anything else, a museum. A deserted museum. Nobody to greet him at the ticket office, nobody in the cloakroom. Hesitant at first, The Master had taken this as a sign of charitable welcome, and pushed on inside, starting to walk through the warm, desolate rooms, still half numbed by the cold, until he had noticed a human presence at the far end of one of the rooms. He had taken off his steamed-up glasses and approached. The human figure had turned out to be a girl, standing motionless in front of a painting. The Master had come up behind her to get a better look at both the girl and the painting.

The painting was St Francis Preachingto the Birds by Oskar Laske. The girl was very beautiful. She was staring at the painting as if it were a window wide open on a dream, and she was crying: her cheeks were streaked with big tears.

“…by a study carried out on a number of Asian and African men who had died of other causes, more than 30 per cent of fifty-year-olds given post mortems present signs of a carcinoma in the prostate…”

The Master ignored this bothersome interference and reestablished radio contact with the spaceship of memories.

Without a second thought, he had asked her in his laboured German, “Why are you crying?”

“Because St Francis was good,” the girl had replied.

“…in eighty-year-olds the figure reaches 70 per cent. In any case, from now on you’ll have to undergo regular PSA tests, but I feel moderately optimistic in your case.”

When they left the museum, it was still snowing, although less hard. She had put her arm through his as if afraid of getting lost. They had taken shelter in a café near the Naschmarkt, where they had laughed, drunk hot tea and eaten Sachertorte.

“…without a prostate you will encounter a number of small inconveniences…”

Then they had ended up in a pension behind the opera house and made love all night, while outside it had snowed without respite.

“Such as impotence…”

Where did that memory come from? Did the prostate have a memory and was this one of its reminiscences? Why had he never thought of it again until today? Were they his memories or his organ’s memories? The Master wondered.

“Are you listening to me?”

The Master left the girl sleeping in the unmade bed in the pension, and nodded at The Urologist.

“I was saying that without a prostate you will encounter a number of inconveniences, such as impotence. But at your age certain appetites are probably…”

The Urologist said this as if he were a priest hearing the dying confession of a whoremonger. The Master looked at him sternly.

“Impotence, and incontinence.”

“Am I going to piss in my pants?”

“You see, since the demolition phase of the prostatectomy, the bladder, the distal urethra and the periurethral and perineal muscles have remained intact. Except that we had to reconstruct your urinary tract, establishing communication between the bladder and the remaining urethral segment. This will cause you problems with urination.”

The Master got off the spaceship. “Are you saying I’ll have to wear incontinence pads?”

“You’ll have to undergo rehabilitative treatment to strengthen the muscle fibres and the perineal region.”

“Doctor, I’m in the running for a very important prize. There’s a strong possibility I’ll win it. I can’t risk pissing myself onstage.”

“It’s just a matter of doing some very simple exercises, for instance, interrupting the flow of urine.”

“…”

“When you feel the urge, go to the toilet and try to interrupt the flow suddenly… then start again… then interrupt it again, on and off, on and off… like a tap… Treat it like a game.”

“…”

“Another very useful exercise worth repeating is this.”

The Urologist stood up, walked solemnly to the middle of the room and planted his feet firmly on the floor.

“Back straight, legs open…”

The professor threw his weight onto his thighs, bent his knees and slowly crouched, down, down, down, as if intending to shit on the carpet.

“Then pull yourself up by contracting the perineum.”

The Urologist got back into a standing position, although not without a certain effort. A bead of sweat glistened on his tanned forehead. Then he straightened his coat and sat down again.

“Another exercise, which also involves contracting the perineum, is to contract it as much as possible and then…” The Urologist coughed twice, sharply. “Or else blow your nose. All these exercises involve the abdominal muscles. The important thing is to keep up the contraction. Is that clear?”

“Almost. How do I contract the perineum?”

“Clench your buttocks, damn it! Now we really should end there. Oh! Perhaps before you go you’d be so kind as to inscribe something… for my wife, you know, she has all your books.”

The fact that she had all of them didn’t mean she’d read them, but The Master kept this thought to himself.

The Urologist opened a drawer and took out a book still in its cellophane wrapper, which he proceeded to tear off without any embarrassment.

The book, thought The Master, was like one of those whales that die choked by plastic bags. On the cover was an erotic scene, a detail from a Greek vase. It looked less like a book than a brochure for a guided tour of an Etruscan tomb. And then they complain my books don’t sell, thought The Master. Angrily, he grabbed the pen.

“To?”

“I’m sorry?”

“What’s your wife’s name?”

“Oh, Sara. But, well, actually… it isn’t for my wife… Write ‘to Alessia’, or rather, no, ‘to Alessia’ sounds wrong, write ‘for Alessia’.”

So now as well as teaching me how to pee, he also has to teach me how to write, thought The Master.

Behind the trendy glasses, The Urologist’s eyes oozed self-satisfaction.

The biro traced a nervous inscription on the title page. As he autographed the copy with a grimace, he was already trying to contract his perineum—or at least to clench his buttocks…

“My secretary will give you an information leaflet summarizing the exercises, along with a measuring cup and a urination diary.”

“A measuring cup? And what the hell is a urination diary?”

“It’s a diary in which you note down the frequency with which you urinate, and the volume of urine you expel. It’s a very useful tool. Please keep it with you at all times and write everything down, symptoms, sensations and so on… Anyway,” said The Urologist, “don’t worry, you have in front of you… I won’t say a bright future, but at least a future. Which isn’t to be sniffed at.”

He turned a dazzling smile on The Master and held out his hand. The Master shook it without vigour. As he left the consulting room, his steps made no noise on the carpet. It was as if he were floating. Could a man without a prostate actually be lighter? How much did a prostate weigh?

The Master’s questions remained unanswered. He paid the secretary for the consultation: two more like this and the advance from The Small Publishing Company would be gone. The secretary handed over the urination diary—a little notebook with a dark cover—and an anonymous-looking plastic measuring cup. Of the two things, he couldn’t have said which was the more demeaning. The secretary came to his aid.

“Don’t worry, it comes in a bag,” she said, inserting the measuring cup into the top of the bag and immediately extracting it again, as if the bag could bite. Suddenly The Master had an idea. Instead of heading for the exit, he turned on his heels. The secretary watched him anxiously, unsure whether or not to intervene. Without knocking, he walked back into the consulting room. The Urologist, who was on the phone, instinctively looked up and covered the receiver with one hand.

“Excuse me for a moment… What is it?”

“Could you give me the scan?”

“What’s the matter, missing your prostate?”

There was a fearful thud, and glass showered the room like dew. The Beginner felt tiny fragments of glass frost his bare legs, and a weak current of air filled the room, made the curtains billow and lifted the corners of the tablecloth. Glass everywhere, on the carpet, on the cupboards, in the kitchen sink.

“Darling, where are you?”

The crash had woken The Girlfriend.

“Here.”

He gently moved the curtain, then drew it right back.

“Are you all right?”

“Yes.”

“What happened?”

He walked barefoot, a fragment of glass lodged in his right foot. He brought the foot up to the height of his left knee, twisting the sole inwards, and extracted the splinter. A small amount of blood came out. He didn’t feel any pain, although he probably would later. But first of all, before anything else, there was that dark patch in the middle of the terrace. Whatever it was.

He advanced towards the dark—or rather, black—patch—or rather, mass—in a corner—or rather, in the middle—of the terrace, two metres—or rather, one metre from him, and two from what remained of the pane of glass.

“What was it?”

“…”

A huge black bird lay lifeless on the terrace, its half-open beak looking like a congealed streak of lava, its eyes a cobalt blue, its stiff legs pointing skywards, its wings outspread as if crucified.

“That’s disgusting… What is it?”

Standing in the doorway, her breasts pushing against her nightdress, The Girlfriend looked on in horror as The Beginner walked towards the bird. He was silent for a while.

“A parrot.”

The police helicopter flew over the ring road around Rome, bestowing its blessing from the sky on a sesquipedalian traffic jam between the Cassia Bis and Flaminia exits. From above, the tailback looked like a steel lizard sleeping in the sun. Among the vehicles caught in the bottleneck, there were two which deserve closer attention.

Neither of the two drivers was in a position to know the reason for the tailback. It was in fact due to a rather delicate operation: the removal by the fire brigade of a nest of white storks (Ciconiaciconia) from a speed camera. The presence of the winged couple had interfered with the sophisticated equipment, which explained why it had recently been malfunctioning, resulting in a large number of fines and an equally large number of appeals.

Now although the drivers of the two cars worthy of closer attention were as unaware of each other as they were of the storks, there was a relationship between them, one that was both coincidental and elective. Not so much because the two of them were listening to the same song on the same radio station, which can happen, but because they were two of the three finalists for the same Prize.

The Writer looked at the woman on the seat beside him. The woman was silent. The Writer raised the volume of the radio:

…y me pintaba las manos y la cara de azul…

…pienso che un sueño parecido no volverá mas…

The Beginner lowered the volume of the radio and looked at the cardboard box on the seat beside him. In the mysterious darkness of the box, something was about to happen.

All this was going in inside these two cars caught up in the traffic jam. The Writer was on his way somewhere, The Beginner was coming back from somewhere. But where?

“To the sea?”

“To the lake.”

He had never liked lakes. They had always made him feel really sad, like empty restaurants, cover bands, fifty-year-olds on motorbikes and inflatable swimming pools in gardens. He had only said it for fear of meeting someone who might know him, which would have been quite likely if he had headed for Fregene or Circeo on a fine day like today.

She was passing through the city, or so she had said, and had hired a car.

“Would you like to drive?”

“You drive on the way there. I’ll drive on the way back.”

She had agreed to this pointless arrangement with a touch of amusement, as if it were one of the games they had played when they were younger. The Writer had wanted her to drive so that he could get a better look at her. If only she’d take off those sunglasses! Then The Writer could read her intentions in her eyes.

How many years had passed since he had last seen those eyes, sometimes as calm and clear as an Alpine lake, sometimes green and sparkling like a beetle’s wings?

They had taken the Via Cassia, heading north. As she drove, she occasionally pushed back the blonde hair that kept falling over her face and nervously touched the frames of the big Bakelite glasses that only a diva could have worn with the same nonchalance.

He would have liked to talk, to tell her everything that had happened between the last time they had seen each other and now, but he couldn’t concentrate enough to find the words (which may seem strange for a writer, but there it is). And not only because of the inhibition her beauty had always exerted on him, and not even because he did not really know where to start—but rather because something was interfering with his thoughts. And that something was the feeling that he had forgotten something important, as if he had not switched the gas off before leaving home, or had left his car with the headlights on. The food for The Baby? No, that wasn’t really a problem, The Filipino would pick it up (talking of whom, was he back yet?).

As they got farther from the city and the landscape became less oppressive, the unpleasant sensation also began to abandon him, as if the origin of the sensation were the city itself, or something undefined but now too distant to harm him. Warehouses gave way to cultivated fields, vineyards and vegetable gardens, villages with curious names, cut in two by the road like watermelons split on market stalls, old men on benches in squares or at the tables of bars looking impassively at the passing lorries.

The car with The Writer and the mystery woman on board was rolling down the Via Cassia on a journey without direction and without time.

This may be the moment to reveal the identity of the mystery woman: she was the great love of The Writer’s youth, and for the purposes of her fleeting appearance in this story we shall call her The Old Flame, not so much because she’s old, no, that wouldn’t be very tactful, but because it’s an old story, an affair that once flamed passionately and is now like a lamp with its wick dry.

We can talk freely about her, given that The Second Wife is in her office and can’t hear us. She is sitting at her desk, replying to the mountain of e-mails that have accumulated during the night and the early hours of the morning.

Some time later, just before The Second Wife stepped away from her desk for her lunch break, The Writer and The Old Flame were walking beside the lake, which was streaked with silvery light.

They were walking unhurriedly, already drawn into the tranquil lakeside rhythm. They sat down first at the tables of a café, then moved to those of a restaurant, one of the many which, with the somewhat homespun optimism so common in the provinces, had already put tables outside.

They drank house white and ate seafood salad (even though they were at the lake) and fish (even though they were still at the lake) with potatoes.

At last she took off her glasses, and he saw her eyes. They were girlish eyes, just as he remembered them, still bright, but obscured somehow by an invisible veil of sadness, like a pale sun behind a cloud of ash.