Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Polygon

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

'Five engrossing, resonant stories here, with no weak links' ― The Herald The world's first UNESCO city of literature, Edinburgh is steeped in literary history. It is the birthplace of a beloved cast of fictional characters from Sherlock Holmes to Harry Potter. It is the home of the Writer's Museum, where quotes from writers of the past pave the steps leading up to it. A city whose beauty is matched only by the intrigue of its past, and where Robert Louis Stevenson said, 'there are no stars so lovely as Edinburgh's street-lamps'. And to celebrate the city, its literature, and more importantly, its people, Polygon and the One City Trust have brought together writers – established and emerging – to write about the place they call home. Based around landmarks or significant links to Edinburgh each story transports the reader to a different decade in the city's recent past. Through these stories each author reflects on the changes, both generational and physical, in the city in which we live.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 205

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE PEOPLE’S CITY

THE PEOPLE’S CITY

In support of the OneCity Trust

Foreword by

Frank Ross, The Rt. Hon. Lord Provost of the City of Edinburgh

Introduction by

Irvine Welsh

First published inGreat Britain in 2022 by Polygon,an imprint of Birlinn Ltd.

Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.polygonbooks.co.uk

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Introduction © Irvine Welsh, 2022

‘The Finally Tree’ © Anne Hamilton, 2022

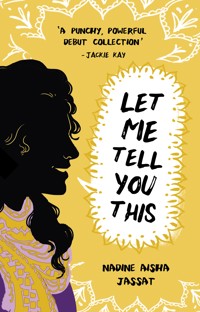

‘In Loving Memory’ © Nadine Aisha Jassat, 2022

‘In Sandy Bell’s’ © Alexander McCall Smith, 2022

‘Broukit Bairn’ © Ian Rankin, 2022

‘On Portobello Prom’ © Sara Sheridan, 2022

ISBN 978 1 84697 601 8

EBOOK ISBN 978 1 78885 485 6

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available onrequest from the British Library.

Typeset in Bembo by Polygon, Edinburgh

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

CONTENTS

Foreword

Frank Ross, The Rt. Hon. Lord Provost of the City of Edinburgh

Introduction

Irvine Welsh

The Finally Tree

Anne Hamilton

In Loving Memory

Nadine Aisha Jassat

In Sandy Bell’s

Alexander McCall Smith

Broukit Bairn

Ian Rankin

On Portobello Prom

Sara Sheridan

Author Biographies

About OneCity Trust

FOREWORD

It gives me great pleasure to see the fourth anthology to be published in aid of the OneCity Trust; along with the continued support of three of Edinburgh’s most famous authors and original contributors from our first book, OneCity, published in 2005.

In 2022, I welcome the addition of three female authors, who all, through their own personal connection to Edinburgh, add their unique writing style to this eclectic collection of stories. The reader will be enraptured by this anthology of short stories, and its Edinburgh landmarks, the majority of which are set in times gone by and add a historical twist that make the book hard to put down.

The aim of the first book in 2005 was to promote the message through the OneCity Trust that Edinburgh ‘should no longer be a divided city but one city with one voice’. Sixteen years later, and the division remains evident from a report published in 2020 by the Edinburgh Poverty Commission, ‘A Just Capital: Actions to End Poverty’, which finds that over 77,000 citizens are living in poverty, including one in five children. This shows an increase of over 25 per cent in the last five years.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has also caused great hardship to many in the city, bringing increased unemployment, the need for food banks, along with a decline in mental health. Data poverty has increased also as the world turns to online meetings as a way to communicate with others. Schools used online teaching methods with children; yet some homes didn’t have access to the internet or adequate equipment. The inequalities have been huge, and the pandemic has exacerbated the divide in society.

The OneCity Trust has been fortunate to work with a number of key organisations over the past six years to deliver community benefit funding to projects in the city. The support of the City of Edinburgh Council, Travis Perkins Managed Services, CGI UK Ltd, ENGIE, CCG (Scotland) Ltd and City Fibre has seen tens of thousands of pounds being distributed to local communities. Together, we will work to end the inequality and poverty which continues to divide our city, with a vision that, one day soon, we will have a Thriving, Welcoming, Fair and Pioneering city for one and all.

I would like to thank all of the authors for giving their time and story writing talents to our book; the OneCity Trust is indebted to you. To Travis Perkins Managed Services and Morrisons Energy Services, thank you for your financial support which has helped us produce this book. To our readers, thank you for purchasing this book, which will raise funds for the OneCity Trust to continue its legacy to make Edinburgh ‘OneCity’.

Frank Ross, The Rt. Hon. Lord Provost of the City of Edinburgh

INTRODUCTION

Since I contributed to the first OneCity Trust book in 2005, I’m sorry to say not much has changed in our city – or in society as a whole.

The poorest parts of Edinburgh are still characterised by underemployment, low wages, and insufficient access to essential services, as deprivation thrives exponentially, passed down from generation to generation like a devastating disease. Now more people than ever before have been pulled down onto the breadline, with many more households struggling to make ends meet as benefits are continually cut and community funding is slashed. Working people that might once, fifteen or twenty years ago, have been considered middle class, are now shackled with debt, as proven by the lengthy queues outside food banks.

These issues stem from the fact that in places like our capital – a global tourist attraction – the focus has shifted from serving the needs of locals to feeding the bottomless trough of neoliberal capitalism. Therefore people are largely deigned not to exist in a city increasingly redesigned to attract tourists, wealthy students, businesses, and housing developers. The people who bring income are paramount, and our modern culture of cheap Airbnb accommodation, landlordism and commercial development constantly feeds the dominant narrative telling us that so-called ‘legacy citizens’ are irrelevant to the city’s progress. They are simply displaced casualties of an economic, social and technocratic order that says they have no relevance in the modern world. After all, if Edinburgh does not court the international market, politicians argue, another city will simply take its place, with the income and investment going to other communities around the world.

In short, the people who actually live in Edinburgh, especially in our poorer communities, are at best forgotten, at worst ignored.

Government agencies and the poverty industry are not friends of our communities. All major transnational bodies, governments local and national, and all major political parties, are accepting of an economic system that sees poverty as a (regrettable or otherwise) consequence of the enrichment of the already super-wealthy. Whether their posturing is ‘national’ or ‘global’ such agencies are basically the hirelings of the one per cent. Therefore, any attempts to challenge this paradigm are piecemeal and token, with progressive policies rarely scratching the surface of such systemic issues.

So, what can be done to ensure this damaging legacy doesn’t continue decade after decade? I believe it is time we accept that the state is no longer the driving force for change. It has become purely a tool of capital, and now cannot have a role in redistributing power and wealth through the society and community it purports to represent. Therefore our citizens have to find the voice and the confidence to start putting their own structures in place – and there has never been a better time to do it. The fact that football fans now feed their local communities through at-turnstile-collections for food banks, and that organisations like Helping Hands brought sport and recreation back into the schemes, tearing some children from screens and a future of morbid obesity, shows that the problems of the community have their solution in the community. A disinterested state, run only to service the needs of the untaxed global and national wealth-looters, will only, at best, offer crumbs on a grudging whim. Our citizens need to take the power and responsibility for their own destinies into their own hands.

Over the past 18 months or more, the pandemic has highlighted the existing inequalities that already plagued our neighbourhoods, shining a spotlight on the hunger, debt and hardship that goes unacknowledged in the mainstream media and political parties (unless through some token pious bleating as they assume the neoliberal agenda). In the middle of a time when family and friends were pushed achingly apart, communities rallied together, installing vital safety nets that the Government had, year after year, pulled out from under them. People were given a glimpse of what our society could look like if we lived in a more benign world that actually put people first, and that is a legacy we need to build on and help flourish.

As a writer, I naturally believe art and culture is vital for encouraging this empowerment to take root. In low employment and low economic areas, the arts are the only real way people can express themselves, and that’s why projects like the OneCity Trust book are so important. The purpose of this collection of stories, just like the last, is to encourage people to have the confidence to express themselves. Because doing this involves articulating your own needs and taking action to meet them.

So while angry that the great welfare state, constructed after the horrors of the Second World War, has been decimated and warped beyond repair by the super-wealthy, I’m proud to be associated with a venture that is about art and culture – another one of the casualties of a neoliberal order that reduces them to profitable entertainment.

Brian Eno once said: ‘culture is what you do when you do what you want to do, rather than what you have to do.’ We citizens are now irrelevant to the super-rich and their state. The system needs to dupe us into giving it our seal of legitimacy every five years or so. That’s about the extent of our participation in the decisions that affect our lives. But the good news is that they are irrelevant to us. They either can’t or can barely offer us work or food. We can now do that for each other, and spend more time doing what we want to do. First we have to learn how to be free. Art and culture is how we do this.

Irvine Welsh

The Finally Tree

ANNE HAMILTON

MONDAY

I’ve found him, Ali. But . . .

But.

There was always going to be a but, and it was always going to be a big one. Alina wondered which of the big three D’s it would be. Dead. Demented. Dispossessed. An irreverent trinity that she’d found fitted most of life’s ‘buts’.

On Inverleith Row, she checked the time and saw she was early; she always was. This was a pilgrimage. The plane, a train to Waverley, then the bus skimming the New Town, all were fuelled on her anticipation of entering the East Gate through its magical scent of nostalgia and anticipation.

I’ve found him, Ali. But . . . It was the soundtrack to her long journey home. Even as she’d dozed, read, stared from screen to window and back again, the rhythm propelled her: de dah de dah de dah; I’ve found him, Ali but; de dah de dah de dah. Unconsciously, she’d tapped her toes in time with it.

She bent to pick at a scraggly dandelion pushing through the cracks in the pavement. She blew on the fragmented petals, then gently separated them and began counting: Fin’s found Jamie, he’s found him not, he’s found him, he’s found him not . . .

It had to be that, didn’t it? And, of course there was a but. Anyone who disappeared for twenty-five years returned with A Story. If they returned at all.

Alina had never in twenty-five years regretted her decision that Fin should be adopted, never. Other events from back then she did question, though, and that text, that but, quite possibly meant she had been found out. Fin had been looking for his birth father for nigh on ten years, now, and naïve or stupid, as time rolled on without news, she’d learned to live with the risk.

‘Ali . . .Ali . . .? Alina.’

The voice penetrated. When she looked up, there he was, Fin, coming towards her. He reminded her of Jamie she realised with shock: floppy blond hair, and slim. Even down to the leather jacket – or was her mind playing tricks? Wishful thinking, perhaps. She put up her hand to wave and stood waiting.

‘Ali. I thought I was going to have to chase you round and round the gardens and in and out the dusty bluebells.’

‘Sorry, I was miles away. How are you? Is everything okay?’ Alina searched his face; he looked nothing other than pleased to see her.

‘Everything’s fine.’

‘Really?’ I’ve found him Ali, but . . . Surely this was the – first – moment of truth. ‘Really, Fin?’

‘Oh, you mean my text?’ Yes. So, er, did my “but” look big in that, Ali?’ He raised one eyebrow, his party trick; Alina couldn’t do it.

‘Oh, very funny.’ She relaxed slightly and leaned in to hug him.

‘Coffee?’ he asked. ‘Inside or takeaway?’

A smattering of rain picked up speed, helped by a sudden gust of wind, and Alina shivered. A quick glance up at the sky, leached of all colour, made up their minds and they crossed towards the café.

‘You grab that.’ Fin suggested, gesturing to a table at the edge of the busy room. ‘I’ll queue. Latte, right?’

‘Please.’

There was always a moment at the Botanics, jet lagged or not, afraid her life was about to implode or not, when the years fell away and Alina was in limbo between past and present. It was here, seventeen years ago, that she’d met Fin for the first time. She’d been horribly nervous then, as well, worried that this unknown little boy would be bored, mooching ahead with his hands in his pockets and scuffing his feet. After all, it was one thing to know you had a birth mother on the fringes – Fin’s was an open adoption: cards and gifts twice a year; annual school photograph; holiday postcard – another to give up a precious afternoon to the stranger she was. But Alina had underestimated Fin, and the powerful mix of logic and curiosity that made up his eight-year-old self.

‘We come here a lot, maybe every week,’ he’d told her, dumping his dinosaur backpack on the ground and rooting in it. ‘Do you?’

‘I used to, when I lived in Edinburgh.’ She’d hesitated, then, wondering whether to add that this was where she’d first met his birth father, but it seemed too much too soon.

‘Me and my dad made a map so I can show you my favourite things. Look.’ Fin held up a jagged scroll tied with a piece of ribbon.

‘Like a treasure hunt?’ she’d asked. ‘I love treasure hunts.’

‘Me too.’

Unfurling the map and following its crayoned dotted lines, had broken the ice, and they paced the paths, crossing ornamental bridges, like the ghosts of Victorian gentlefolk, politely discussing how to seek out the tiny rhododendrons hiding in the Rock Gardens.

‘I don’t know what a rhododendron looks like,’ Alina had whispered, truthfully, and he’d patted her arm with the gravity of a little old man. ‘It’s okay, we’re all learning together – that’s what my teacher says.’ Fin had marched her to the glasshouses next, giddy in the arid lands and the tropical rainforest, daring her to believe in red pineapples and the promise of early morning tree frogs. He’d flagged a bit then; he was hungry. ‘Have you got a sneaky snack in your bag? I’m not asking for sweeties.’ He’d squinted hopefully. ‘But sometimes when people meet for the first time they do bring sweeties, don’t they?’

When she’d produced a big bag of stupidly expensive be-ribboned jelly beans she’d picked up just in case, his eyes lit up with such glee, she glimpsed the toddler she’d never known, all red wellies and Paddington duffle coat. He ripped the bag open and shared the ones he hadn’t spilled, counting out – sternly equally – the sugary jewels into their hands.

Alina smiled now, re-tracing that first journey with the comfort that Fin’s memories were as rosy-glowing as her own. Two, then three, four, and increasingly more times a year they met here, regular as the seasons, solid as the earth from which the magnificent gardens grew.

‘Here you go.’ The grown-up Fin snapped back into focus as he set a mug of coffee and a slice of millionaire’s shortbread in front of her. ‘Thinking back?’ he said with a grin.

Alina nodded. ‘Daydreaming, really. Jet lag, too.’

Fin sipped his drink. ‘I bet. How is work?’

‘All good. Hoping we’re robust enough to avoid this coronavirus thing, but . . .’ She shrugged.

‘Yeah. Aren’t we all.’ Fin pulled a face. ‘Kind of puts things into perspective.’

Did it though? I’ve found him, Ali, but . . . She settled on a non-committal, ‘Hmm.’ In the ensuing silence, she looked down at the table, rearranging her cup, then his, two spoons and a plate, until they were in perfect alignment. She knew Fin’s eyes were on her. ‘So,’ she said, meeting them.

‘So.’

They looked at one another for a long, long second.

‘You’ve found him, then,’ Alina said. ‘Jamie.’

‘Ye-es.’ Fin looked . . . not angry, not disappointed, but perplexed.

Hopefully, it was just one of the big three D’s. Ah, no, Alina retracted the thought half-heartedly, she didn’t mean that, but she had to know what she was working with. She’d start at Ground Zero: ‘He’s dead, isn’t he?’

Fin folded his arms and sighed. ‘No. Well, yes. In a way.’

Ah, thought Alina. The Story.

‘The thing is . . .’

She watched him search for the words. Was he protecting himself, or her? Both of them, perhaps.

‘Ali, Jamie doesn’t exist anymore.’ It wasn’t like Fin to be oblique.

‘I don’t understand,’ she said.

‘I’ve found my birth father who isn’t my birth father.’

‘What?’ Alina knew immediately she’d over reacted. ‘Sorry. Go on.’

‘Look. In a sense, he is alive and well, but—’ Fin grinned faintly; Alina was too wound up – ‘but, there’s no easy way to tell you this.’

For the first time in forever, she wanted to snap at him. She bit it back, well aware it was Jamie she was irritated with. No, it wasn’t; it was herself. ‘Go on?’

‘Ali, for the last eight years, Jamie’s been known as Sanna.’

‘Sanna?’ Alina’s brow creased.

‘Yes. Jamie, my birth father, is now Sanna. He’s been living as, I mean he is, she is, a woman.’

Alina picked up her empty cup and pretended to take a drink. Then another. The shock on her face was genuine, easily masking the little trickle of relief. ‘Right,’ she said, nodding slowly, mind whirling. ‘Right. What else?’

‘Er, most people might think that was enough, Ali.’ After a few seconds, Fin went on. ‘She’s an academic, apparently. A professor.’

‘Jamie? He’s a professor – of what? You’re joking?’ Alina hastily wiped the smirk from her lips; to laugh felt inappropriate. More relief slipped through.

‘No, Ali.’ Fin’s voice was gentle. ‘Sanna is.’

‘God. Yes, of course. Right. Sanna.’ Crockery rattled around them. The hiss of the coffee machine sounded like an exploding boiler. The world tilted for a second.

Whatever Alina had expected, it wasn’t that. Being transgender didn’t fit into the three Ds. It was something to be celebrated, surely. It was . . . Alina stopped, stumped. She didn’t know what it was. And not only that, but a professor, of all things. ‘Is that it? Any more surprises?’ She held her breath.

‘That’s it.’

‘I don’t know what to say,’ she admitted.

‘I know you don’t. Neither did I.’ Fin shook his head. ‘You don’t have to be poker-faced and unshockable. I wasn’t. It is bloody weird.’

Alina gathered her wits, trying to recalibrate. She hadn’t been found out. Yet. ‘How do you feel?’

‘I’m fine now, I think.’ Fin picked up the cup in front of him and swirled the cooling dregs around as if he were reading tea leaves. He paused and looked up as if assessing his feelings. ‘Yeah, I am. I mean, that somebody got in touch in the first place is really the biggest shock, you know.’ He sat back. ‘It’s not as if I’ve been looking for my dad, is it? I’ve got a great dad.’ He spoke more fluently now, and Alina knew this was rehearsed, he’d been over it and over it, making sense of it – that was Fin; that was her too.

‘Are you going to meet her?’

‘I want to, but . . .’

Alina’s heart flipped a beat. Was this where it all fell down? ‘All right,’ she said. ‘What?’

‘She, Sanna, wants to see you first.’

‘Me? Why?’

‘I don’t know. Apparently, she said it would probably make sense to you. Does it?’ Fin looked at her hopefully. ‘Will you meet her?’

‘Oh . . . Yes. Yes, of course, I will.’

‘Great. I knew you would, Ali.’

His trust in her made her want to cry; she didn’t deserve it. Neither did he notice she hadn’t answered his first question, and they sat in silence for a few minutes. Alina felt weak. It was the jet lag, just the jet lag.

Fin stood up and held out his hand. ‘Come on, you look shattered. You should be at home.’

‘But the gardens, the Finally Tree, Fin. We always . . . I mean, don’t you want—’

‘Ali. The tree has been here tens if not hundreds of years. It’ll be here after we’re gone. It’s not the Faraway Tree, waiting to change worlds.’

It was a bit, though. Alina slowly stood up, placing her bag over her shoulder. ‘I need to sleep,’ she agreed, embracing the firmer ground. ‘It seems like days since I got here.’

‘Are you okay, Ali? I mean, Jamie was,’ Fin hesitated, ‘is your past.’

‘My past. Exactly.’ If only he knew. Alina mustered a proper smile. ‘I’ll be fine, Fin. I just need to take it in. Your “but” may have looked big in the text but it certainly didn’t look anything like this.’

‘Things change, Ali. People change.’

But they didn’t, not in the time warp in Alina’s mind. ‘I’ll always be your baby’s father, Alina,’ he’d promised, when they’d made their pact all those years ago, ‘I’ll never change.’ But that had been Jamie.

Where was it going to leave the three people they had become?

1994

Pure luck had seen Alina accepted into Edinburgh University at the same time as Jamie. They were from different worlds.

‘People like me don’t go to university,’ Alina had said cheerfully.

‘People like me always do but it doesn’t mean we should,’ Jamie countered.

Both were out of step rather than out of their depth. It wasn’t a case of looking back and realising it, they’d always known it. Jamie seemed to live far more in the moment than everyone else around them, Alina included. Even at nineteen – at nine, if she were honest – she’d been a planner, which served her well, but Jamie made her appreciate the here and now and, if there was no appreciation to be had, they poked fun at it, and the moment got better. It was his irreverence she cherished, in this strange student world where political correctness and straight-talking overlapped like a weird Venn diagram, foreign to the housing scheme she’d grown up in.

The first time she had seen Jamie was at a cross-discipline lecture for Social Work (her) and Computer Science (him) students, eyeing each other up like alien species. The second time, they’d noticed each other at the Botanics, wryly bonding in such a non-student-like environment. Geographically, both lived near-ish: Alina with her grandparents in Granton (‘the wrong end,’ she parroted to Jamie, whose head it went over) and Jamie in Trinity, where his parents had bought him a flat (‘I asked them not to,’ he stressed).

‘Can I be your partner in those cross-dressing classes?’ he asked, making her giggle. ‘I’m an out-and-proud nerd, and very scared of your lot.’

‘Yes, please. I’m scared of them too.’ She’d taken out a marker and drawn a smiley face on each of their hands to cement the deal.

‘Are they always that uptight?’ he’d asked.

‘Hmm. Nobody cried today.’ It had started to drizzle and Alina was busy shoving her notebook into her bag. ‘That’s a first.’

‘Ha ha . . . Wait, you’re serious? For fuck’s sake.’ He’d tried to purse his lips into a whistle but was trying too hard not to laugh.

‘Sadly not.’ Alina found his grin infectious. ‘What makes you think I’m not the chief crier?’

‘Algorithms. I’m a computational physics genius and I worked out the probability.’ They walked out the gate, and turned left together. ‘Joke. It was your shoes.’ He pointed down at her feet, then his own. ‘Same as mine. It was a sign.’

Alina followed his gaze; well, they both wore trainers that fitted somewhere on a large spectrum of ‘red’. He’d found a nice way of not saying they were both plain ordinary.