Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

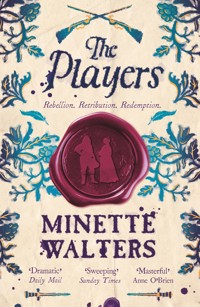

Readers love THE PLAYERS 'Totally riveting... Perfect. 'I was transported every time I picked up this highly imaginative story' 'Everything I love about historical fiction' 'This is historical fiction at its best' 'Good to see female characters having strong roles' 'I would recommend it to anyone who enjoys history, literature and a "jolly good read"' Who will save them from the gallows? England, 1685. Decades after the end of the civil war, the country is once again divided when a pretender to the throne incites rebellion against King James II. Angered, the king orders every captured rebel to be hanged, drawn and quartered. As the country braces for carnage, the formidable Lady Jayne Harrier and her enigmatic son, assisted by the reclusive daughter of a local magistrate, contrive ways to save men from the gallows. Secrets are kept and surprising friendships formed during the dark days of the Bloody Assizes, in a dangerous gamble to thwart a brutal king's thirst for vengeance... 'Fascinating ... told with the masterful skill of a true storyteller' Anne O'Brien 'An immersive joy that will stand the test of time' Elizabeth Chadwick

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 612

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in trade paperback in Australia in 2024 by Allen & Unwin

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2025 by Allen & Unwin,an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

This paperback edition published in 2025 by Allen & Unwin

Copyright © Minette Walters, 2024

The moral right of Minette Walters to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

No part of this book may be used in any manner in the learning, training or development of generative artificial intelligence technologies (including but not limited to machine learning models and large language models (LLMs)), whether by data scraping, data mining or use in any way to create or form a part of data sets or in any other way.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN: 978 1 80546 317 7

Allen & Unwin

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

PRAISE FOR

The Swift and the Harrier

‘This well-researched, atmospheric tale is as gripping as any of her thrillers’ — Good Housekeeping

‘A cleverly craft ed combination of romance and adventure story’ — Sunday Times

‘The author best known for her crime fiction sets this enthralling tender love story against the brutal background of the English Civil War’ — The i

‘Minette Walters, a stalwart of crime fiction, is excellent on the horrors of civil war in Dorset, and Swift is a memorable and spirited heroine’ — The Times

‘Both gripping and fascinating. The civil war in Dorset is evoked brilliantly, the characters are real and intriguing and the love story tender.’ — Elizabeth Buchan, bestselling author of The New Mrs Clift on

‘A sweeping historical romance with a very appealing central character … a great story well told’ — Andrew Taylor, bestselling author of The Ashes of London

‘This is historical fiction at its finest … Jayne is a fantastic character, a woman very much in a man’s world, living and working to bring succour to those in need’ — Belfast Telegraph

‘I have loved every moment of this brilliantly evocative saga of struggle, love and danger set against the horrors of civil war’ — S W Perry, bestselling author of The Jackdaw Mysteries

PRAISE FOR

The Turn of Midnight

‘Walters writes a mean historical drama…compelling’ — Daily Telegraph

‘A mammoth tale’ — BBC History Magazine

‘Stunning’ — Daily Express

‘This intriguing read makes excellent use of outstanding historical detail and depth…an impressive literary adventure’ — Canberra Weekly

‘Vividly readable…Walters’ transition away from crime is complete, bringing her a wealth of new fans’ — Herald Sun

PRAISE FOR

The Last Hours

‘Atmosphere, imagination and narrative power of which few other writers are capable’ — The Times

‘A staggeringly talented writer’ — Guardian

‘Walters’s skill and subtlety in portraying the suffering and disarray of a feudal society in which disease rampages and God has seemingly gone mad is masterly. And, as with her bestselling suspense novels, the psychological drama is gripping.’ — Daily Mail

‘Wonderful and sweeping, with a fabulous sense of place and history’ — Kate Mosse, No 1 bestselling author of Labyrinth

‘An enthralling account of a calamitous time, and above all a wonderful testimony to the strength of the human spirit. I was caught from the first page.’ — Julian Fellowes, creator and screenwriter of Downton Abbey

‘A vividly wrought and powerful story. With The Last Hours, Minette Walters has brought her impressive skill as a writer of psychological crime to create a dark and gripping depiction of Medieval England in the jaws of the Black Death.’ — Elizabeth Fremantle, author of Firebrand

‘Minette Walters is a master at building engrossing tales around a single, life-shattering event’ — Washington Post

‘A gripping read. Walters uses this oft en grisly tale to explore questions of class relations, gender relations, and the societal aft ermath of the Norman conquest’ — Sydney Morning Herald

Other books by Minette Walters

The Ice House (1992)

The Sculptress (1993)

The Scold’s Bridle (1994)

The Dark Room (1995)

The Echo (1997)

The Breaker (1998)

The Shape of Snakes (2000)

Acid Row (2001)

Fox Evil (2002)

Disordered Minds (2003)

The Devil’s Feather (2005)

The Tinder Box (2006)

Chickenfeed (2006)

The Chameleon’s Shadow (2007)

Innocent Victims (2012)

A Dreadful Murder (2013)

The Cellar (2015)

The Last Hours (2017)

The Turn of Midnight (2018)

The Swift and the Harrier (2021)

For Jenny, Ricky, Matt and Jane

All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players. They have their exits and their entrances; and one man in his time plays many parts.

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, AS YOU LIKE IT

Faber est quisque fortunae suae.(Every man is the architect of his own fortune.)

APPIUS CLAUDIUS CAECUS

THE AFTERMATH OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR

IN THE TEN TURBULENT YEARS that followed the brutal Civil War between Parliament and the King, which ended in victory for Parliament and the execution of Charles I in 1649, only five delivered stable government. These were under the leadership of the Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell, whose control of the New Model Army imposed order, albeit through a military dictatorship. A king in all but name, Cromwell filled the void left by the empty throne, but his early death in 1658 threatened to plunge the country into turmoil once again.

With no strong figurehead emerging from its own ranks, Parliament voted to restore the monarchy, and Charles I’s heir, his eldest son, was invited to return as King in 1660. Dubbed ‘the Merry Monarch’, Charles II was likeable, good-humoured and charming. He reigned for twenty-five years and, by steering a more intelligent course than his father, never lost the loyalty of his subjects. His single failure was his inability to produce a legitimate heir with his wife, Catherine of Braganza, although he was known to have twelve illegitimate children by his many mistresses, the eldest being the Duke of Monmouth.

On Charles II’s death in February 1685, the only successor with a legal claim to the throne was his brother James, Duke of York, younger son of Charles I. However, James’s conversion to Catholicism in 1669 had set many against him, and voices of discontent were heard across England, warning that a Catholic king would once again subject his country to the tyranny of Rome.

PROLOGUE

The Hague, Holland, April 1685

IT WAS A FAVOURABLE NIGHT to stand unseen in the shadows of an alleyway. The sickle moon was obscured by clouds and a cool mist rolled off the sea, shrouding The Hague in fog. The watcher eased his position occasionally to relieve an aching muscle, but his movements were slight. Dressed in black, with a wide-brimmed hat pulled low over his face, he escaped notice in the darkness that surrounded him.

The alleyway led off a street of tall, elegantly gabled buildings and, despite the mist, the watcher had a clear view of the Duke of Monmouth’s house. In contrast to the muted glow of candles in the upper chambers of its neighbours, flaring lanterns hung from brackets along the facade, throwing light across the cobbles. The watcher had known where Monmouth lived from previous visits to The Hague, but even if he hadn’t, the duke’s penchant for flying his standard from a pole above his front door made his whereabouts obvious to anyone with an interest in his activities.

In the three hours since the watcher had taken up position in the alleyway, eight men had presented themselves at the door and not one had attempted to hide his face. Rather, they had seemed to revel in drawing attention to themselves, pounding on the panels and announcing themselves loudly in English to the servant who answered. The watcher had been certain of only four names before he arrived. Now, he knew them all and questioned their foolishness in making their conspiracy so obvious. Were they ignorant or careless of the spies that haunted The Hague and reported everything they saw and heard to the court of King James?

He judged it to be close to midnight when the guests emerged again, and he counted them off as they left. The last to leave was the Earl of Argyll, and his annoyance was evident as he stepped onto the street and rebuked Monmouth’s servant for being dilatory in handing him a lantern. At fifty-six Argyll was the oldest of the plotters and the least content to be living in exile in Holland, a fact he made clear in every letter he wrote. The watcher listened to his footsteps disappearing into the night and was unsurprised to see a cloaked figure follow behind him a few moments later.

Conscious that there might be others, he remained where he was, and his patience was rewarded within five minutes when a second figure passed in front of the guttering lanterns on Monmouth’s house. Shortly afterwards, the servant appeared from the side of the building to quench the flames with a candle snuffer, and the thoroughfare was plunged into darkness. Even so, the watcher waited on, listening for the scuff of shoes or boots on stones, but when nothing disturbed the stillness of the night, he slipped from the alleyway and trod softly across the cobbles.

He found the narrow alley from which Monmouth’s servant had emerged more by feel than sight, but once inside a glow at the far end of the right-hand wall led him forward. As he’d hoped, the light was coming from the kitchen quarters, and a glance through the narrow window showed him that Monmouth’s valet was the only occupant of the room. Relieved not to have to explain himself to a Dutch maid, he rounded the corner of the house and used the light from a larger window to locate the door. Aware that his sudden appearance would shock the valet, he removed his hat before lifting the latch and stepping inside.

He smiled in recognition as he crossed the floor and stationed himself in front of the fire. The man was an old soldier who had been serving Monmouth for nearly twenty years. ‘Good evening, John. I trust you’re well.’

The valet clapped his hand to his heart. ‘Mercy me! Is that you, my lord?’

‘As I live and breathe.’ He tucked his hat beneath his arm, removed his gloves and began to unbutton his coat.

The elderly valet’s expression was easy to read, for he was clearly suspicious of the visitor’s motives in coming. He knew well that his master had enemies in England, from where he guessed the visitor had travelled, though his chances of learning anything from the other’s expression were negligible; the younger man was too well-schooled in the art of deception.

‘May I ask what you’re doing here, my lord?’

‘Trying not to be seen,’ came the amiable response. ‘The Hague is awash with men keen to record the names of your master’s guests. It seemed safer to enter through the kitchen quarters.’

‘I meant, what are you doing in the master’s house, my lord? Is he expecting you?’

‘Not at all, John. My intention is to surprise him, in the hope that he’ll listen to me. He appears to be keeping dangerous company.’

The valet looked for weapons as he relieved the visitor of his hat and gloves and assisted him out of his fog-saturated coat, but if the visitor was hiding anything it wasn’t obvious. Clad in tight-fitting shirt, waistcoat and britches, anything deadly would have been visible.

Reassured, he answered honestly. ‘I’m forbidden from commenting, my lord, but you’ll have no argument from me if you’ve come to remonstrate with him. He’s been in need of good advice since his father died, but he rejects mine in favour of the whisperings of schemers.’

‘Has he retired to bed?’

John draped the coat over the back of a chair and angled it towards the fire to dry. ‘Not yet, sir. He sits in the parlour with a bottle of cognac staring at his father’s portrait. It’s most unhealthy. Do you wish me to announce you?’

‘No need. Just tell me which door to enter.’

‘The second on the left, my lord.’ The valet opened a cupboard and removed a glass. ‘You’ll need this if you’re to partake of the cognac. The master will be insensible within thirty minutes if you leave him to drink the bottle alone.’

‘Has he eaten?’

‘Not since breakfast. He lives on his nerves these days.’

‘Is there food in the pantry?’

‘Only raw mutton for tomorrow. This evening’s guests ate the last of the bread and cheese.’

The visitor reached down to extract ten guilders from his coat pocket and exchanged them for the glass. ‘Buy what you can at this hour, keep some for yourself and bring the rest to the parlour. I’ll be insensible myself if cognac is all that enters my stomach. I haven’t eaten since leaving England at dawn yesterday and lost most of what I consumed into the sea.’

John’s gaze was sympathetic. ‘A rough crossing, sir?’

‘Rough and long,’ came the wry response. ‘It’s not a journey I’d wish on anyone, least of all your master.’

‘Be sure to tell him that, sir. He has a fanciful notion that his return to England will be as calm as when he left it two years ago.’

Rumour had it that Monmouth was selling everything he had of value, and his reduced circumstances showed in the modest furniture of the parlour. There was no uniformity to the chairs, donated by well-wishers, which stood about the rough-hewn table at the centre. The room was warm enough, being small and benefiting from glowing embers in the hearth, but to the visitor’s eyes the single candle and the dark oak panelling on the walls gave it more the look of a monk’s cubicle than the drinking chamber of a future king. The only adornment was a portrait above the mantel of the fireplace—a representation of Charles II in the style of Sir Peter Lely—which took the place of a crucified Christ in this gloomy cell.

‘Leave me be,’ muttered Monmouth when he heard the creak of the door behind him. ‘I’m wearied of your scolding, old man.’

‘I’ve a mere two years on you, James, and you’ve yet to hear me scold you.’

Monmouth turned his head from contemplation of the portrait. ‘Goddamn it!’ he cried. ‘Are you real?’

The visitor placed his glass on the table and stepped forward to grip Monmouth’s hand. ‘As real as you.’ He assessed the duke’s face in the flickering light of the candle and thought him barely changed from when they had first met twenty-two years ago. He still had the same boyish good looks and charming smile of the fourteen-year-old who had captured the hearts of his father’s people. ‘My mother sends her regards and wishes you to know that she shares your grief,’ he said, drawing out a chair and lowering himself to the seat. ‘As do I. Your father’s death was most sudden and unexpected.’

‘He was poisoned,’ Monmouth declared bitterly, filling the visitor’s glass with cognac and passing it to him with an unsteady hand. ‘Join me in drinking to the death of his murderer.’

‘Gladly. What name does he go by?’

The words came out in a slur. ‘King James of England . . . hated uncle . . . hated namesake . . . Catholic traitor . . . enemy of Protestants . . . vile slayer of his brother.’

The visitor shook his head. ‘I can’t drink to a lie, James. Let’s toast your father’s memory instead.’ He touched his glass to Monmouth’s. ‘To our Merry Monarch, a man much loved and mourned by his people—and by none so much as his firstborn son.’ He took a swallow of brandy, welcoming the heat it generated in his throat and belly.

Tears sprang into Monmouth’s eyes. ‘He was taken before I could reconcile with him. He died believing me capable of killing him.’

The reference was to the Rye House Plot of two years previously, when members of the Whig party in Parliament had devised a plan to assassinate King Charles and his brother in order to ensure that a Protestant succeeded to the throne of England. The attempt was never made, but the names of the conspirators were revealed when one of their number turned informer. Amongst those cited were the Duke of Monmouth and the Earl of Argyll.

‘Your father wouldn’t have let you flee to Holland if he thought you as culpable as the ringleaders,’ the visitor said matter-offactly. ‘You’d have suffered the same fate as Lord Russell and the eleven others who were executed.’

Monmouth couldn’t have been as drunk as he seemed because his response was immediate and fluent. ‘But I had no culpability in the plot,’ he protested. ‘I never participated in it, and those who said I did were lying. They hoped to save their own skins by implicating me.’

The denial was so practised that the visitor wondered if Monmouth had succeeded in persuading himself of his own innocence. He took a second sup of brandy and responded with a falsehood of his own. ‘I believe you, my friend. You’ve more sense than to involve yourself in treason.’ He chose the word deliberately, but Monmouth’s only reaction was to shed more tears.

‘Why could my father not see that?’

‘He would have done in time.’

Monmouth raised his gaze to the portrait again. ‘It’s too late. Did he speak of me before he died?’

‘I don’t know. He had a seizure on the second of February and, despite the efforts of his doctors, passed from life four days later.’

Monmouth’s tears dried abruptly. ‘Men of fifty-four don’t have seizures for no reason.’

The visitor shook his head. ‘My mother would disagree with you. One of the attending physicians sent her a copy of his notes, and from the symptoms he described, she believes the King’s heart and lungs failed him. His health had been deteriorating for months, causing pain from near-constant gout, ulcers and breathlessness, and she’s of the view that these were the outward symptoms of inner disease. For that reason, she urges you to ignore the rumours of poisoning, and says further that if anything hastened his death, it was the unremitting purges and bloodletting performed by the royal physicians.’

Predictably, Monmouth seized on the single phrase that suited him. ‘The rumours of poisoning must be rife in England if your mother has heard them.’

‘They are, but only the most ardent Catholic-haters give them credence. Wiser heads ask what your uncle had to gain by having his brother killed.’

‘The throne.’

‘But why now?’ the visitor asked reasonably. ‘Why not next year or the year after? He’s younger than your father and could have waited a decade if necessary. He’s too aware of how the English view his conversion to Catholicism to show impatience to become king.’

Monmouth’s eyes narrowed. ‘Have you come at his request? You seem mighty keen to play the advocate for him.’

‘You know me better than that, James. I’m here as your friend to give you more honest advice than the discontents who mutter in your ear.’

‘Which discontents?’

‘Argyll for one. You’re being used by a practised deceiver. His promises to deliver Scotland for you are as false as his stories of poisoning.’

The glass in Monmouth’s hands quivered violently. ‘What can you possibly know of Argyll’s business?’

The visitor gave a low laugh. ‘The same that King James and his advisers know. Argyll’s letters are regularly intercepted and he’s criminally loose-lipped about your plans for rebellion.’

The duke rose to his feet and leant against the mantel, presenting his back to his guest. ‘I’m not responsible for what he writes.’

‘But you’re party to his plan, James. Every meeting you’ve had with him and your fellow conspirators has been witnessed and reported by men in the pay of your uncle. The King knows the names of everyone involved.’

No answer.

‘If you need better evidence, I’ve been watching your house since sunset and I wasn’t alone in doing so. Two spies, as well-hidden as I, followed Argyll after he left. I’m ignorant of whether they were Dutch or English—perhaps one of each—but be in no doubt that your intrigues are as well known here at the court of Prince William as they are in London.’

A stifled groan issued from Monmouth’s mouth. ‘What other claims are being made about me?’

‘That you’re soliciting your supporters for money, particularly those in the south-west. Your letters are intercepted as frequently as Argyll’s, and you press your need for capital funds in all of them.’

‘My father’s death has left me wanting.’

‘Yet you’ve recently pawned your jewellery and silver for three thousand pounds, and the mother of your mistress has promised you another three thousand.’

Monmouth kicked a burning ember. ‘Where did you learn that?’

‘From a source in Prince William’s court. I cannot emphasise enough that you have no secrets, James. You and Argyll have raised less than twenty thousand pounds between you, and that sum is insufficient to purchase the ships, troops and weapons needed for a successful invasion of England and Scotland. The King’s army totals above ten thousand, and there are many more thousands of local militiamen who are sworn to his service. Tell me how you expect to defeat them without troops of similar numbers and experience.’

The silence that followed this question was interrupted by John, who entered the room with a platter of food. ‘You forget the love the people have for my master, sir,’ he said, placing the plate on the table. ‘Lord Argyll assures him that every able-bodied Protestant in the British Isles will rally to his standard once he sets foot ashore.’

Monmouth rounded on him angrily. ‘Cease your damned meddling!’

The elderly valet stood his ground. ‘Lord Argyll says, too, that the master can land anywhere and walk to London with naught but a stick in his hand. The people will follow him wherever he goes.’

‘Out!’

The valet searched the visitor’s face. ‘Is there anything else I can do for you, sir?’

The visitor smiled. ‘No, thank you, John. You’ve provided me with everything I need.’ He waited until the valet left, then spooned pickled herring onto a hunk of bread. ‘Will you eat with me, James? Honest Dutch food will do more for your health and temper than a diet of cognac.’

With another petulant kick at the embers, Monmouth resumed his seat and selected a wedge of edam. ‘As long as you end your lecturing. Do you think me such a fool that I take everything Argyll says on trust?’

Since Monmouth’s recklessness was matched only by his poor judgement, that was precisely what his guest thought, but he avoided an answer by chewing on the bread and pickled herring.

‘And you shouldn’t believe anything John says,’ Monmouth continued. ‘His mind is so addled he forgets his own name. He’ll have forgotten yours by tomorrow. He picks up snippets from the other side of the door and weaves them into nonsense.’

The visitor piled more herring onto bread. ‘My ship sails at dawn, so I can’t stay beyond another hour if I’m to reach the harbour without being seen. Is there any news I can give you about your acquaintances in England?’

Monmouth frowned. ‘Why the haste to leave?’

‘I can’t afford to be linked with you, James. I’m too fond of my head to lose it over an ill-judged plot that can’t succeed. The Civil War is still strong in people’s memories and they won’t willingly engage in conflict again.’

‘A peaceful rebellion needn’t involve war.’

The visitor shook his head at his friend’s naivety. ‘In your fantasies, perhaps, but not in reality. From the moment you set foot on English soil, you will be committing an act of high treason. Your uncle may be as bad as you paint him, but he’s your father’s only legitimate heir and has Parliament’s authority to defend England against all usurpers. He will send his army against you whether his subjects want him to or not.’

Monmouth stared into his glass. ‘Many believe my claim to be as valid as his.’

‘Not in Parliament, where it matters. A son born out of wedlock cannot succeed to his father’s throne.’

A twisted smile formed on Monmouth’s lips. ‘But a Catholic brother can.’

The visitor nodded. ‘The arguments haven’t changed, James.’

‘And if the people decide differently?’

‘The choice isn’t theirs to make, and any who are foolish enough to take up arms on your behalf will be condemned as traitors. Your uncle has a long reach and his justice will be harsh. Remember that before you encourage others to join a venture that is doomed to failure.’

There was only the slightest of hesitations before Monmouth answered. ‘You concern yourself unnecessarily,’ he said lightly. ‘I made clear to Argyll this evening that his plans are his own, and I’m neither so foolish nor so rash as to engage with them. He left in anger, which you will know if you watched his departure.’

The visitor acknowledged the point with a tilt of his glass, but he disbelieved the rest of what Monmouth had said. Lies had always tripped off his hot-headed friend’s tongue more easily than truth.

He fingered the small paper sack of white arsenic in his waistcoat pocket. It would be a simple sleight of hand to drop the contents into Monmouth’s brandy glass, but he foresaw more problems than solutions if murder was suspected. Legitimate or not, Monmouth was of royal blood, and King James needed no better excuse to break his treaties with Holland than the killing of his nephew on Dutch soil.

The visitor made his way back to the harbour along lanes he knew well from previous visits. As King Charles II’s personal envoy, he had crossed the Channel regularly, carrying letters from the King to his nephew Prince William of Orange, Stadtholder of staunchly Protestant Holland. Prince William was the son of Charles and James’s sister, placing him fourth in the line of succession to the English throne, and the sensitive nature of the correspondence between the two men had necessitated secrecy. For this reason, the envoy had grown more accustomed to moving at night than during the day.

The Anglo-Dutch wars, fought sporadically for twenty years as each country battled for trade dominance around the globe, had ended in victory for Holland in 1674. The settlement that followed had held, but distrust had lingered on both sides. The same was true across Europe as old alliances fractured and new ones formed. The legacy of the Continent’s thirty years of religious wars had led to France under Louis XIV becoming the leading power in Europe, and animosity towards French imperialism was rife.

Holland had strongly resisted Louis XIV’s attempts at invasion, but Prince William, ever suspicious of Catholic France, saw merit in cementing peace with Protestant England. To that end, he had petitioned King Charles to approve his marriage to Mary, the eldest daughter of Charles’s brother James and second to James in the line of succession. The negotiations had taken time, not least because James opposed the match. As a Catholic, he believed it was against God’s law for first cousins to marry, though sceptics thought his objections owed more to the risk that William and Mary posed to his own succession, both being Protestant and with near equal claims to the English throne.

In the interests of peaceful cooperation, King Charles had overruled his brother, and the cousins had wed in 1677. Thereafter, the only matter of personal interest that had concerned the two heads of state had been the Duke of Monmouth’s exile to Holland in 1683. Neither had wanted him to create problems for themselves or their governments, and while King Charles lived, there had been little to report; on his death, the warnings of an imminent rebellion began.

King James, unwilling to engage in secret or open correspondence with his son-in-law, dismissed his brother’s envoy and employed an army of spies to inform him of Monmouth’s plans. In contrast, Prince William drew the envoy closer and used his own spies to intercept and read the reports sent to King James.

The envoy’s route took him to Vissershaven, the fishing port, where light from the ever-open taverns spilt onto the cobbled quay. He stood there for several minutes in thought, then retrieved the sack from his waistcoat pocket. His intended target had been Argyll, but his chances of gaining access to the earl had always been slim. With only minor regret at his failure—murder would have troubled his conscience—he dropped the sack into the water and turned towards the lights.

The door of De Drie Vissen was open and he cast around for his Dutch counterpart. Spotting him in a darkened corner, conversing earnestly with a man whose profile bore a strong resemblance to the second spy to follow Argyll, he withdrew to the opposite corner and prepared to wait.

Jan Hendriksen joined him some quarter-hour later, slapping two filled tankards on the table between them. He spoke in English, being less understandable to eavesdroppers. ‘If I didn’t know you so well, I’d call you a liar if you said you met with Monmouth. My informant watched the street for five hours, and named or described every man he saw—whether they entered the duke’s house or not—and you were not amongst them.’

The envoy grinned. ‘But I saw him well enough. He showed himself minutes after the King’s man who was dogging Argyll.’ He touched his tankard to Jan’s and took a swallow of frothy beer. ‘I have only bad news for Prince William. Monmouth is in too deep to stop now. He claimed he’s broken ties with Argyll, but he was lying. They had words, but I would guess the argument was more about timing than whether or not to proceed. My best advice for Prince William is to honour his treaties with England and keep a healthy distance from his cousin. Any hint of collusion with Monmouth will give King James an excuse to name his daughter and son-in-law as conspirators in the rebellion.’

‘All of Holland, too, no doubt.’

‘Indeed. Do you know when Argyll is due to sail?’

‘In a couple of weeks. They plan to wait in the Zuider Zee for a favourable wind.’

‘And Monmouth?’

Jan took a swallow from his own tankard. ‘He’ll not be ready before June. He’s acquired three ships but little else. I’m told he lacks the necessary funds to purchase muskets, let alone field guns. To date, he’s mustered a mere five dozen mercenaries to support his campaign, and Prince William wonders if we shouldn’t incarcerate him for his own safety. He seems completely ignorant of the strength of the force that will be sent against him.’

The envoy steadied a drunken sailor who stumbled against him. ‘Wees dankbaar dat ik een vergevingsgezinde man ben,’ he said. ‘Doe het nog een keer en ik gooi je de straat op.’*

The sailor muttered an apology and staggered back the way he had come. The noise in the tavern was loud enough to cover their conversation, but the envoy waited until the sailor was out of earshot before continuing. ‘Argyll has convinced Monmouth that England is rife with anti-Catholic feeling and that so many will rally to his cause he’ll march to London without a shot being fired.’

‘Only a fool would believe that. With his meagre army, he’ll be routed within days.’

‘Indeed, but Monmouth needs to believe it. His entire wealth is invested in the venture. To withdraw now will bankrupt him. He’s a gambler and always has been. He’ll continue whatever the risks and hope to charm his uncle into exiling him back to Holland if he fails.’

‘Will that work?’

The envoy shook his head. ‘Argyll is right about the anti-Catholic feeling. King James will make an example of Monmouth, if only to deter future rebellions.’ He drained his tankard. ‘I’ll write my report aboard the ship. The captain is pledged to delay our departure until it’s finished.’

‘How long?’

‘Two hours at most. Tell your man to look for the Kent Maiden.’ He reached over to grasp Jan’s hand. ‘Vaarwel, mijn vriend.* I’m guessing it won’t be too long before we see each other again.’

Jan returned his grip. ‘What will bring you back?’

‘King James’s intemperance,’ the envoy answered, rising to his feet. ‘He’ll earn his country’s hatred if he demands that Monmouth’s followers pay the same price as their leader. Even if their numbers are limited by a quick defeat, there’ll be no loyalty to a Catholic king who orders the mass execution of Protestants.’

_____________

* Be thankful I’m a forgiving man. Do it again and I’ll toss you into the street.

* Farewell, my friend.

REBELLION

Summer 1685

A PAMPHLET PRINTED AND DISTRIBUTED THROUGHOUT DORSET ON THE EVENING OF 11 JUNE 1685 (AUTHORSHIP UNKNOWN).

A Strange Arrival by Sea

A man of Royal descent stepped ashore this day in our fair port of Lyme Regis. Handsomely attired, he declared himself to be the Duke of Monmouth, come from Holland to claim his rightful place as King of England. A multitude lined the shores and streets to see him, and many more hastened in from outlying villages as word spread that the son of our late, lamented King Charles was amongst us. He delivered a speech on the defence and vindication of the Protestant religion, advising the crowd of his intention to liberate the Kingdom from the tyranny of Catholicism. Rousing cheers greeted his words, but this writer noted that the fervour came from the younger members of our community while older, wiser heads stayed silent.

Those who lived through the brutal Civil War that ravaged our country forty years ago viewed the Duke of Monmouth’s pitiful fleet of 3 small ships, his abject army of 82 souls, and derisory weaponry of 4 light field guns and 1500 muskets with alarm. The cause of Protestantism is a worthy one, but such a paltry force is insufficient to mount a rebellion against King James. This writer urges every reader to resist the Duke of Monmouth’s call to arms.

You have been warned.

THE PENALTY FOR HIGH TREASON IS DEATH BY HANGING, DRAWING AND QUARTERING

ONE

Wimborne St Giles, Dorset, 8 July 1685

WORD THAT THE DUKE OF Monmouth’s short-lived rebellion had ended in defeat at Sedgemoor in Somerset reached the neighbouring county of Dorset within hours. Few doubted the truth of the news, for the uprising had been doomed once the siren voices that had lured the duke from exile fell silent under threats of punishment for high treason. It was said that he had been promised an army of trained militiamen, but only labourers and artisans armed with pitchforks and clubs had rallied to his standard. It mattered not that many in the south-west had sympathy with his cause; England’s quarrelsome history of the last half-century meant people were wary of making their allegiances known.

Hard on the heels of the reports of King James’s victory came rumours that Monmouth and several of his aides had fled the field of battle in a bid to escape capture. Some claimed he was making his way west to Wales, others that he was heading south-east towards the Dorsetshire coast in the hope of paying a fisherman to give him passage back to Holland. Whatever the truth, no one who lived and worked on the Earl of Shaftesbury’s estate, some thirty miles north of the nearest port, expected to find themselves at the centre of the search for him.

As dusk fell on 7 July, a regiment of soldiers under the command of Lord Lumley and another of militiamen led by Sir William Portman encircled part of the estate, claiming to have tracked him to this very place. Acting on information supplied by a peasant woman who alleged that she had seen two strangers cross a hedge into a pea field, Sir William set his company to searching the cultivated land while Lord Lumley’s men tramped the area of scrubland beyond. Nevertheless, despite moving in serried rows and beating the vegetation with their musket stocks, the efforts of both companies proved fruitless.

Lanterns were commandeered from the many bystanders, who had been drawn by curiosity to see if there was any truth in the rumour that the fugitive had chosen their estate as a hiding place, and as Sir William’s militiamen began a second search some shouted that it would make better sense to set fire to the crops and burn the duke out. Sir William, unwilling to pay reparation to Lord Shaftesbury for such wanton destruction, refused, but his irritability grew as midnight came and went without success. His militia consisted of Somerset men, mustered in Taunton where he was the Member for Parliament, and none had any knowledge of the area they were searching. If they had, they would have known of the water-filled ditches beneath the hedgerows and would have tramped those as diligently as the fields.

A message came shortly after dawn on 8 July that a Dutchman had been taken prisoner by another militia some three miles away. Under brutal questioning, he had confessed to being one of the strangers the peasant woman had seen, claiming to have made his escape before Lumley’s and Portman’s cordons had been fully established. He further confessed to leaving his companion, the Duke of Monmouth, behind, saying the duke had been too exhausted to walk. Upon hearing this, Sir William instructed his men to renew their efforts, reminding them that a bounty of five thousand pounds had been placed on the fugitive’s head.

The sun had been up two hours when cries for help echoed across the pea field which the peasant woman had first identified. The shouter was Henry Parkin, and when his fellows ran to his aid he pointed to a patch of brown fabric showing through a straggle of ferns and brambles at the bottom of a ditch. In darkness, it had been invisible; in daylight, it contrasted strongly with the green vegetation above it. Even so, a command to ‘stand and show yourself’ brought no response. Either the garment had been abandoned or whoever wore it was deaf, asleep or dead.

Parkin seized a sword from one of his companions and prepared to thrust the tip into the fabric, but a tall bystander, dressed in black with the white lace bands of a parson about his throat, stepped forward and took hold of his right arm. ‘Piercing him with a blade will not cure his weakness, sir. Allow me to enter the ditch to assist him.’

‘As long as you recognise that the find was mine and will testify the same to Sir William Portman.’

‘I do and will,’ said the parson, easing himself down the bank and pulling aside the ferns and brambles with gloved hands. ‘I have no interest in the bounty.’

The sight he exposed was a sorry one: a human shape, wrapped in a saturated, threadbare cloak, lying on his front in the damp mud of the ditch with his face resting on folded arms and the hood of the cloak covering his head. With no signs of life, the parson stooped to turn the body onto its back, causing the arms to unfold and the hood to fall away, revealing a shaven head and a gaunt, colourless face torn by brambles.

Parkin gave a grunt of disappointment. ‘It’s not him,’ he said. ‘This man’s too old.’

‘Is he dead?’ asked another.

The parson removed a glove and touched his fingers to the unfortunate’s neck. ‘I fear so. There’s no warmth in him. I’ll need your help if we’re to lift his body from the ditch.’

The request was met with shrugs of indifference, as if none thought it worth the trouble. The Duke of Monmouth had been described to them as a man of thirty-five who bore a strong resemblance to his father King Charles II, while the emaciated creature in the mud looked more like a starving vagrant than a pretender to the throne of England. They would have returned to their searching and left the parson to deal with the corpse alone had Sir William not seen their gathering from a hundred yards distant. He arrived at a canter and demanded to know why they were idle.

Parkin gestured behind him. ‘I saw a cloak beneath the ferns, sir, but the man who wears it is too old to be the duke . . . and dead also, by the looks of him.’

Sir William dismounted and pushed through the group to stare down at the upturned face. ‘It must be Monmouth. The Dutchman named him as his companion.’ He raised his gaze to the parson. ‘What attempts have you made to revive him?’

‘None. You reached us as these gentlemen were about to help me lift him onto dry ground. If he’s alive, he’ll need to be warmed and fed before he can speak or stand.’

Sir William drew his own sword with a contemptuous laugh. ‘I don’t have your soft heart, Reverend. Let’s see what a few pricks to the groin can achieve.’

With a sigh, the parson deflected the thrusted blade with his gloved hand, causing the tip to embed itself in the bank. ‘I can’t in good conscience allow you to do that, sir. Whoever this man is, and whether he’s insensible or dead, you’ll be torturing him to no purpose. We can all see that he’s incapable of rising out of this ditch of his own accord.’

‘Do you doubt it’s Monmouth?’

‘I do, sir, for he looks nothing like the description you gave your men. Are you so well acquainted with him that you don’t have doubts yourself?’

‘Who else can it be?’

The parson knelt on one knee to search a pocket of the cloak. ‘A destitute in search of food?’ he suggested, pulling out a handful of raw peas and displaying them on his palm. ‘It’s not uncommon for such people to make their beds in ditches. I buried a woman six months ago who was found in similar circumstances.’

Sir William sheathed his sword with unnecessary force. ‘You’re trying my patience, sir. Your name and reason for being here?’

‘Reverend Houghton. I have business in Ringwood but paused out of curiosity to discover why so many men were drawn to search these fields.’ The parson discarded the peas and replaced his glove. ‘Unless you intend to leave this man in an unmarked grave, I suggest you instruct your soldiers to assist me in lifting him up the bank.’

It is truly said that the margins between success and failure are very thin. Had the ‘corpse’ remained insensible, the parson might have been able to perpetuate the pretence of death; as it was, rough handling caused a sigh of pain to escape the man’s lips, and once he was laid upon the ground a kick from Sir William Portman’s boot brought another.

‘It seems he’s not as dead as you thought, Reverend.’

The parson removed his long black coat. ‘God be praised,’ he murmured, dropping to his knees and bending his head in prayer before laying the coat across the body and speaking clearly. ‘I am a man of the cloth, my friend. My name is Reverend Houghton and I will give you what succour I can while the many gentlemen who surround you question you about your presence here. I seek only to help you and will remain at your side for as long as is necessary. Are they right to think you’re the Duke of Monmouth? If so, you will suffer less by admitting it than subjecting yourself to the same brutal interrogation that a Dutch prisoner endured six hours ago.’

A slow tremor began in Monmouth’s eyelids, but a minute passed before they opened. The parson looked for recognition in the gaze that stared up at him and was relieved when he saw it.

Monmouth moistened his lips with his tongue. ‘Can I rely on your promises, Reverend?’ he asked in a whisper.

‘You can, my friend.’

‘Then you may tell my captors that I am James Scott, first Duke of Monmouth, eldest son of King Charles II and rightful heir to the Protestant throne of England.’

The parson was obliged to use his fists to prevent the captive being dragged by his arms to a cart on the other side of the field. His long service as a soldier and his well-aimed punches left Henry Parkin and one of his comrades with bloody noses, and his obvious ability to deliver the same to anyone else who stepped forward dissuaded others from trying. Sir William Portman, red in the face with fury, threatened him with a horsewhipping if he didn’t stand aside, but the parson apologised and said he could not.

‘My promise to assist this man was not rendered invalid by learning his name, sir. He needs food and water before he can stand, and I have both in my saddle pack.’ He nodded to a dark bay mare tethered to a birch sapling some thirty yards distant. ‘Oblige me by asking one of your men to bring the pack.’

Sir William placed his hand on the hilt of his sword. ‘You’re treading a dangerous path, Reverend. There’ll be no quarter given to anyone suspected of collusion with Monmouth. The man’s a traitor to his King and country.’

‘That may be so, sir, but I doubt King James will want him delivered to London so broken in body and spirit that he’s incapable of facing his accusers. If you think otherwise, continue with your cruelty . . . if not, send a man to my horse.’

It was a battle of wills that should have been won by Sir William, who was supported by a growing number of his militia, but the parson, alone and unarmed, was unyielding. Tall, lean and clad entirely in black apart from the white bands about his neck, with his dark hair falling naturally to his shoulders, he stood his ground fearlessly and cut a more impressive figure than stout Sir William, whose extravagantly curled wig sat askew atop his sweating, rubicund face.

With an abrupt nod, Sir William dispatched a man to fetch the saddle pack. ‘Do you have a personal interest in Monmouth, Reverend?’

‘No more than in you and your soldiers, sir. It’s thirsty, hungry work searching through the night, and you all look in need of food, water and rest. Shall we forget our differences for thirty minutes and share what we have? With so many men guarding him, your prisoner cannot escape again.’

Sir William’s expression said differently, though his suspicion was centred on the parson rather than the man at his feet. It was known that Monmouth had exchanged his clothes with a shepherd the day before in a bid to pass unnoticed, but a more effective and useful disguise would have been to become a man of the cloth with ownership of a horse. Indeed, had Sir William not thought the idea too absurd to countenance, since Monmouth would have been long gone if he’d had a horse beneath him, he would have said the men had switched places already. The parson was the right age to be Monmouth and showed all the confidence of a pretender to the throne.

‘You must forgive my distrust, Reverend Houghton,’ he murmured, taking the saddle pack when his man returned with it, ‘but I’m curious about the contents of your bag.’ He unbuckled the flap. ‘You’re very handy with your fists for a clergyman, and I wouldn’t want a loaded pistol held to my head.’

‘I forgive you readily, sir, and urge you to take all the time you need to satisfy yourself that my intentions are charitable. Meanwhile, if you care to hand me the chalice and the stoppered flagon, I’ll make a start on reviving your prisoner.’

Sir William removed an earthenware bottle. ‘Is it wine?’

‘No, simple water.’ The parson took the bottle and held out his other hand. ‘The chalice, too, please. The prisoner will find it easier to drink from a cup.’

‘Some would say it’s sacrilege to use a holy vessel for such a purpose.’

‘Which purpose, sir? Giving drink to a thirsty man?’

‘Giving drink to a traitor.’

A flicker of amusement appeared in the parson’s eyes. ‘Well, at least God won’t be offended. Jesus would not have allowed Judas to join him at the Last Supper if traitors are beyond forgiveness.’

With a sour smile Sir William handed over the silver chalice and watched with his men as the parson drew the cork from the bottle with his teeth, half-filled the bowl with water and then knelt to raise Monmouth’s head. He spoke quiet words of encouragement as he held the rim of the cup to the duke’s lips, but his bent head and lowered voice meant that not everything he said was heard. Certainly, none of the observers realised that short phrases in Dutch were being seeded amongst the English.

‘Take as much as you need, there is more in the flagon. Vergeet niet wie je bent.* Recall your Bible and know that Jesus said, “If any man thirst, let him come to me and drink.” Vind je moed.† Your strength will come back to you quickly once you’ve eaten. Nederige mannen zijn voor u gestorven.‡ Nod, when you’re able to sit and I will raise you up. Geef ze nu waardigheid door uw acties.§ Do you hear me, my friend?’

‘I hear you, Reverend.’ With a small groan, Monmouth pulled himself into a sitting position and addressed Sir William Portman. ‘If you’ll allow me a little food, I shall endeavour to give a better account of myself. My belly is knotted with cramps through being empty for nigh on a week.’

‘It’s only a day and a half since you fled the field of battle at Sedgemoor.’

‘And it would have pleased me greatly to eat before it, sir, but meals and rest have been in short supply since I arrived in England.’

‘Through your own fault. Your treachery has cost you dear, and you’ll pay the full price when your head is removed.’

A faint smile lifted Monmouth’s lips. ‘Without your mercy, I’ll be dead of starvation before I ever reach London, sir.’ He lifted a thin hand to his emaciated face. ‘If my altered appearance doesn’t persuade you that I’m in the last extremities of hunger and fatigue, my death most certainly will.’

Sir William must have seen the truth of this, because he pulled a muslin-bound bundle from the saddle pack and handed it to the parson. ‘Assist him to eat, Reverend, but know that I will hold you responsible if he attempts to escape once his strength returns.’

Ignoring him, the parson unwrapped the bundle and tore bread from the half-loaf inside. He gave it to Monmouth with a slice of cheese. ‘Eat slowly, my friend, or you’ll make your cramps worse.’ He refilled the chalice. ‘I have water when you need it.’

‘Geen schrik hebben. Ik ben weer mezelf.’*

‘Repeat that in English, please. If it’s Dutch you’re speaking, it’s not a language I know.’

‘Forgive me, Reverend. When I’m weary, I revert to the tongue of my childhood. I was thanking you for your kindness. It takes courage to show friendship to one such as I.’

‘I had no choice once God placed you in my way. Console yourself that He has not abandoned you, however dire your circumstances may seem.’

Thereafter, conversation between them ceased until Monmouth declared himself replete. ‘I doubt I’ve enjoyed a meal so much, Reverend, and with your assistance, I believe I can stand. It’s past time I looked these gentlemen in the eyes rather than stare at their boots.’

The parson removed his coat from Monmouth’s lap to avoid it becoming tangled about his feet and then offered his hand. The duke’s answering grip was stronger than he had expected and it took but a single heave to pull him upright, though Monmouth begged the continued support of his arm while he sought his balance. A bitter east wind bit through his threadbare clothing and, with every joint and muscle aching from having lain in the saturated ditch all night, his pain was obvious. He closed his eyes and muttered to himself in Dutch, seemingly to strengthen his resolve—‘Je hebt genoeg gedaan. Verlaat me nu. Je wekt argwaan als je blijft’*—before stepping away from the parson and addressing Sir William.

‘May I know your name, sir?’

‘Sir William Portman, Member of Parliament for Taunton.’

‘Then I am at your service, Sir William. How do you wish to proceed?’

In his shepherd’s smock and cloak, both wet and stained with mud, he made a comical figure. The garments were too short for a man of his height and exposed the trembling of his knees through the tattered britches.

Sir William barked a laugh and turned to the parson. ‘Does your charity run to giving this traitor your coat, Reverend? You’re of similar height and your long skirts will hide his fear.’

‘I’d rather lend it, sir,’ the parson answered, lifting the garment from the ground. ‘I’m not so wealthy that I can afford to purchase a new one whenever the occasion demands.’ He moved alongside Monmouth and asked his permission to remove the shepherd’s cloak before helping him to feed his arms into the coat sleeves and buttoning the front. ‘You’ll find a folded woollen chaperon at the bottom of my pack, Sir William,’ he said as he inserted the duke’s hands into the gloves. ‘I’ll lend that also, since your prisoner will shiver less once his head is warm.’

Grudgingly, Sir William handed him the hood. ‘How do you expect to retrieve these items, Reverend?’

‘Through your courtesy when you’ve acquired suitable clothes for him, sir. Lord Shaftesbury allows me to minister to his household, so a package addressed to me here at Wimborne St Giles will be safeguarded until my next visit.’

‘It’s not my responsibility to find suitable attire.’

‘You might be wise to try, however,’ said the parson, pulling the hood over Monmouth’s head and tucking the ends inside the coat collar. ‘You’ll need a warrant to make this arrest lawful, and I doubt you’ll persuade a local magistrate you’ve captured the Duke of Monmouth if you present him in peasant’s garb and a borrowed coat.’

‘He confessed to being Monmouth before witnesses.’

‘As would a vagrant if it meant the possibility of food. A magistrate will demand more compelling evidence than a muttered declaration to authorise this man’s transportation to London.’

Sir William scowled, foreseeing endless delays. ‘What do you suggest?’

The parson gestured towards the bystanders. ‘If the story these people have told me about a shepherd exchanging clothes with a well-dressed gentleman yesterday at Woodyates Inn is true, then you should search out the shepherd. In doing so, you will kill two birds with one stone. Not only will the shepherd still have the gentleman’s clothes, but he will also be able to tell the magistrate whether this is the person with whom he traded. It won’t prove the gentleman is Monmouth, but it will prove your prisoner is not a vagrant.’

‘Where’s the nearest magistrate?’

‘One mile away at Holt Lodge. His name is Anthony Ettrick.’

‘Will you take us to him?’

‘Happily, as long as you don’t expect your prisoner to walk. You can see for yourself that he’s incapable of taking more than a step without collapsing.’

‘You’re a demanding man, Reverend. You’ll insist next that I lend him a horse.’

‘There’s no reason why not if you ask for his parole first, sir.’

Sir William saw merit in accepting the parole but not in allowing his prisoner to ride. Instead, he gave orders for the cart to be brought from the other side of the field, permitting his prisoner to sit on the parson’s saddle pack until it arrived. He also saw merit in the parson’s suggestion to seek out the shepherd and offered payment to any bystander willing to take two of his men to where the shepherd could be found. A youth agreed on the promise of half a crown, saying he would never make such easy money again.

Meanwhile, the news that a man had been captured was spreading, and it wasn’t long before it reached the soldiers who were beating the heathland beyond the cultivated fields. The parson, who knew them to be recruits in Lord Lumley’s Regiment of Horse, watched with pretended idleness as one by one they paused in their work. It hadn’t escaped his notice that Sir William had failed to send word of Monmouth’s discovery to Lord Lumley, and his gaze strayed towards the handsomely dressed man sitting astride a black horse to the right of the searchers. Lumley was said to have a temper, and the parson doubted his reaction to learning of the duke’s capture at second-hand would be pretty, since he had pursued the fugitive with even more diligence than Sir William.

The aim of both men was to win approval from the King and Parliament by being credited with the arrest, and the parson was ready to wager money that Lumley would be the victor in the ensuing argument. He was younger and fitter than Portman, and had brought considerably more energy to the search than his stout, red-faced competitor. In addition, he had the advantage of having joined his regiment with the Earl of Feversham’s on the battlefield at Sedgemoor, and would claim to have been present not only at Monmouth’s defeat but also at his arrest.

The parson had learnt these details from talking with one of Lumley’s soldiers the previous evening. The man was complaining that he’d had no sleep since the battle the day before and would have none that night unless the traitor was found quickly. The parson had expressed doubt that Monmouth was in this part of Dorset, but the soldier had laughed and said the traitor had left a trail from Sedgemoor that a blind man could have followed. Had he and the aides who fled with him been better acquainted with the country, they would have moved quietly along footpaths and bridleways. As it was, they had ridden the populated highways at a gallop, and their flight had been witnessed and reported.

The soldier went on to say that Monmouth’s comrades were deserting him faster than rats a sinking ship. They had abandoned their horses and were fleeing on foot in different directions, but two had been seized already and Lord Lumley’s scouts were confident of finding the others. He predicted the duke would be entirely friendless by the time he was discovered, and this view seemed to be shared by the ten militiamen who had been ordered to guard Monmouth while Sir William waited on the road for the shepherd.

‘What sort of a leader loses all his supporters?’

‘A poor one. He should hang his head in shame to be so abandoned.’

‘Perhaps they hoped he’d die if they left him in a ditch.’

‘He would have done if Parkin hadn’t spotted him. You did him no favours, Henry. He’ll suffer worse when the executioner’s axe falls.’

Parkin spat on the ground. ‘I could wish the same for the reverend. It’s not right to give a man a bloody nose for following orders.’