9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

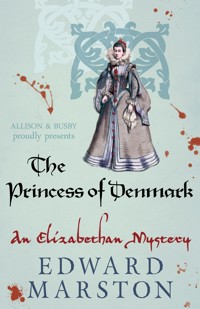

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Nicholas Bracewell

- Sprache: Englisch

Winter approaches and Westfield's Men are out of work. When their widowed patron decides to marry again, he chooses a Danish bride with vague associations to the royal family. Since the wedding will take place in Elsinore, the troupe is invited to perform as guests of King Christian IV. One of the plays they select is The Princess of Denmark - and it will prove a disastrous choice. Westfield's Men soon find themselves embroiled in political intrigue and religious dissension. Their patron, who has only seen a miniature of his future bride, is less enthusiastic when he actually meets the lady, but he can hardly withdraw. Murder and mayhem dogs the company until they realize that they have a traitor in their ranks. It is left to Nicholas Bracewell to solve a murder, unmask the villain, and rescue Lord Westfield from his unsuitable princess of Denmark.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 397

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

The Princess of Denmark

An Elizabethan Mystery

EDWARD MARSTON

To Susan and John with thanks for their warm hospitality in Denmark

Contents

Chapter One

The fire was started by accident. Will Dunmow was a handsome young man, though nobody would have guessed it when they saw his blackened face and charred body resurrected from the ashes. Having come to the Queen’s Head to watch Westfield’s Men performing their latest play, he had enjoyed it so much that he insisted on adjourning to the taproom of the inn so that he could buy drinks for all members of the company. Wine and ale were consumed in glorious abundance and the generous spectator made the mistake of trying to hold his own as a tippler against the actors. It was foolhardy. Only a veteran sailor could drink as hard and as relentlessly as a thirsty player, carousing at someone else’s expense. Dunmow was soon so inebriated that he could barely speak a coherent sentence.

Yet he would not stop. As the taproom slowly began to empty, Dunmow remained, slumped at a table, imbibing merrily to the last. Still exhilarated by the play he had seen in the inn yard that afternoon, he made a brave, if muddled, attempt at quoting lines from it when he could no longer even remember its title. Taking pity on their amiable benefactor, his last two drinking companions offered to convey him back to his lodging but Will Dunmow refused to quit an establishment that had given him so much pleasure. Instead, he rented a room for the night and the two actors – Owen Elias and James Ingram – carried him up the rickety stairs. When they laid him on his bed, he fell instantly asleep.

‘He’ll not wake until doomsday,’ said Elias, looking down at the supine figure with a smile of gratitude. ‘Would that all our spectators were so free with their purses!’

‘Yes,’ agreed Ingram, ‘he was a true philanthropist. And though he drunk himself into a stupor, there was good sport while he did so. He’ll remember this day with fondness, I warrant.’

‘So will the rest of us, James.’

‘Let’s leave the poor fellow to his well-earned slumber.’

‘Good night, good sir,’ they said in unison.

Elias snuffed out the candle that stood beside the bed then he tiptoed out of the room after his friend. Lying in the darkness, Will Dunmow snored gently and dreamt of the performance of The Italian Tragedy that had set his blood racing that afternoon. Instead of being merely a spectator, however, he was now its hero, fighting to save his country from invasion, his own life from court intrigue, and his lover, the beauteous Emilia, from abduction by a foreign prince. Iambic pentameters poured from his lips like a golden waterfall. But his enemies closed furtively in on him. Stabbed by a dozen traitorous daggers, he came awake with a start and sat bolt upright up in bed, relieved that he had evaded his assassins and desperate for a pipe of tobacco by way of celebration.

His hands would no longer obey him, flitting ineffectually here and there like giant butterflies with leaden wings. It was pure luck that one of them finally settled on the pocket in which he kept his pipe. It took him an age to find the tobacco and tamp it down in the bowl of the pipe. Inhaling its rich aroma seemed to revive him slightly and, after several attempts, he finally contrived to strike a spark that lit the tobacco. He drew deeply on its essence, letting the smoke curl around his mouth, down his windpipe and deep into his lungs. The sense of contentment was overwhelming. A rare visitor to the capital, Will Dunmow believed that it had been the happiest day of his life.

Within seconds, he had dozed off again, lapsing into a sleep from which he would never awake. The pipe that had given him such fleeting joy now betrayed him. Falling from his hand, it spilt its glowing tobacco onto the bed. The fire began quietly, burning a hole in the sheet and sending up a column of smoke, imperceptible at first, then thickening and eddying until it filled the whole chamber. Meeting no resistance, the pungent fumes quickly overcame Will Dunmow. Having eaten its way through the bed linen, the fire tasted wood and its appetite proved insatiable. It gobbled everything within reach. By the time that the alarm was raised, the blaze was so loud, fierce and triumphant that it defied arrest.

Panic seized the occupants of the inn. Guests and servants alike leapt from their beds and fled from their rooms in terror. Clad in his nightshirt, Alexander Marwood, the landlord, ran shrieking up and down passageways and staircases as if he himself had been set alight. The most deafening protests came from the horses locked in the stables, rearing and kicking in their stalls as the acrid smoke began to drift into their nostrils. Everyone rushed into the yard. The scene of so much sublime theatre was now in the grip of a real drama. Flames danced madly along one whole side of the building as the inferno really took hold. From the windows of the houses opposite in Gracechurch Street, an audience watched apprehensively in case the blaze would spread to their properties.

Buckets of water were hurled onto the bonfire but they could only stifle its ominous crackle momentarily. After each dousing, it surged afresh and threw dazzling shadows across the yard. The horses were rescued just in time. No sooner had the last frantic animal been led out of the stables with a blanket over its head than the beam above one of the stalls collapsed, sending burning embers crashing into the straw. It ignited immediately and showers of sparks were flung high into the air.

One careless moment with a pipe of tobacco threatened to bring down the entire inn. At its height, the conflagration was so furious and uncontrollable that the whole of the parish appeared to be at risk. And then, suddenly and unaccountably, the miracle occurred. It began to rain. Nobody noticed it at first. Even those who stood aghast in their night attire did not feel the early drops. The fire had warmed them through so completely that they were impervious to any other touch. The storm then intensified, turning a fine drizzle into a gushing downpour and making people run for cover. Rain lashed down with competitive ferocity, matching itself against the blaze and determined to win the contest.

It was an extraordinary sight. Unchecked by human hand, the bonfire slowly gave ground to the deluge. Yellow flames were gradually extinguished. Billowing smoke was steadily beaten away. In place of the hideous roar there came a long, spiteful, exasperated sizzle as the fire reluctantly yielded to a superior force. It still burnt on for another hour but its venom had been drawn. Though providential rain had saved much of the inn, a sizeable amount had been destroyed beyond all recognition. Somewhere in the middle of the debris, quite unaware of the chaos he had caused, lay Will Dunmow.

‘We are done for, Nick,’ said Lawrence Firethorn sorrowfully. ‘Our occupation is gone.’

‘The Queen’s Head can be rebuilt.’

‘But what of Westfield’s Men in the meantime?’

‘We do exactly what we did when we last had a fire,’ said Nicholas Bracewell. ‘We quit London and take our talents elsewhere.’

‘That was easy to do when the weather was fine and travelling was not too onerous. But the summer is past. Who will want to trudge around the provinces in cold, rain and fog? Who will relish the idea of putting their shoulders to carts that are stuck ankle-deep in muddy roads? No, Nick,’ he added, stroking his beard ruefully, ‘we have been burnt out of existence.’

It was the following morning and they were standing in the yard, appraising the damage caused by the fire. Wisps of smoke still rose from some timbers, making it impossible for them to be moved by the servants who worked among the ruins. On the previous afternoon, Lawrence Firethorn, the company’s actor-manager, had taken the leading role in The Italian Tragedy and convinced everyone there that they were watching treachery unfold in the Mediterranean sun. Not even his manifold talents could conceal the truth now. The inn yard was a scene of utter devastation. Galleries where spectators had once sat no longer existed. Rooms where guests had stayed were empty shells, silhouetted against the grey sky. Nicholas Bracewell, a sturdy man in his thirties, was only the book holder with the troupe but he was always the first person that Firethorn turned to in a crisis.

‘What are we to do, Nick?’ he asked.

‘The first thing we must do,’ replied the other practically, ‘is to help in every way to clear up this mess. We owe that to the landlord.’

‘We owe that scurvy knave nothing!’

‘This disaster affects us all. We must honour our obligations.’

‘Had I been here when the fire started, I’d have been obliged to toss the landlord into the middle of the inferno. For that’s where the wretch belongs. A pox on it!’ he cried, seeing the very man approach. ‘Here comes the little excrescence. I’ll wager he blames us for all this.’

‘Then leave me to do the talking,’ suggested Nicholas, only too aware of Firethorn’s long-standing feud with Alexander Marwood. ‘This is not the moment to enrage him even further.’

Marwood walked on. Sullen at the best of times, he was now thoroughly dejected, his eyes dull, his body slack, his movement sluggish. The nervous twitch that usually animated his ugly face was strangely quiescent. All the life had been sucked out of him, leaving only a hollow vestige.

‘A word with you, sirs,’ he began with a note of deference.

‘We are listening,’ said Nicholas. ‘There’s much to discuss.’

‘I am on the brink of ruin.’

‘Surely not. The fire was bad but nowhere near as destructive as the one that burnt down the whole inn. You learnt from that dreadful setback, Master Marwood. You replaced the thatch with tiles and it slowed down the progress of the blaze.’

‘Yet it did not stop it from wreaking untold havoc, sir,’ said Marwood, indicating the shattered remains with a sweep of a skeletal arm. ‘My livelihood has been all but snatched away from me. I must talk to you of compensation.’

Firethorn’s ears pricked up. ‘I’m glad that you mention that,’ he said, entering the conversation for the first time. ‘Because we can no longer play here, Westfield’s Men have sustained the most inordinate losses. How much compensation do you intend to pay us?’

‘Pay you?’

‘As soon as possible.’

‘But I am talking about the money that is due to me,’ said Marwood, shaking off his torpor to adopt a combative pose. ‘It’s you who should pay the compensation, Master Firethorn.’

‘Not a single penny, you rogue!’

‘You were the cause of this catastrophe.’

‘I was nowhere near the Queen’s Head last night!’

‘Nevertheless, I lay the blame at your door.’

‘How can that be?’ asked Nicholas, stepping between the two men before Firethorn could strike the landlord. ‘We are as much victims of this disaster as you, Master Marwood.’

‘Your actors set fire to my inn.’

‘That’s a serious allegation.’

‘Yet one that I can uphold,’ said Marwood, wagging a finger under his nose. ‘Master Dunmow slept under my roof last night.’

‘I remember him well – a pleasant young fellow and the soul of generosity. He put a great deal of money in your purse.’

‘Then took it straight out again.’

Nicholas blinked in surprise. ‘He stole from you?’

‘In a manner of speaking. The fire started in his room.’

‘How do you know?’

‘Because we have the chamber directly above,’ said Marwood. ‘My wife is a light sleeper. It was she who first became aware of the danger. By the time we got to it, the room below was a furnace.’

‘Did your lodger escape?’ said Nicholas with concern.

‘He was too drunk to move. Yes – and that’s another thing for which you must bear the responsibility.’

Firethorn was scornful. ‘I told you that the rascal would blame us, Nick,’ he said. ‘Take him away before I lay hands on him.’

‘Let me hear all the facts,’ said Nicholas, gesturing for him to be patient. ‘Continue, Master Marwood. You claim that the fire began in the room below you. How?’

‘How else?’ retorted the landlord. ‘With the candle.’

‘What candle?’

‘The one I left alight in his room when they carried him up to it. Two of your men, Master Firethorn,’ he stressed. ‘They bore him up the steps between them. When they put him to bed, they must have forgotten to snuff out the candle. In the course of the night, Master Dunmow must have knocked it over and set my inn ablaze.’

‘That’s pure supposition.’

‘The finger points at the Welshman and his friend.’

‘Owen Elias?’

‘The very same. He drank till the very end.’

‘Yet remained sober enough to carry a man to bed,’ observed Nicholas. ‘I have more trust in Owen. He’d never leave a candle alight in such a situation.’

‘Then how did the blaze start?’

‘Divine intervention,’ said Firethorn with a grim chuckle. ‘God finally tired of your miserable visage and lit a fire of retribution to send you off to Hell where you belong.’

‘You were to blame,’ accused Marwood, voice rising to a pitch of hysteria. ‘If it had not been for your play, Master Dunmow would never have come near the Queen’s Head.’

‘If it had not been for your heady wine,’ argued Nicholas, ‘he would never have taken a room here. You served him enough to make him drunk and incapable.’

‘Only because your actors urged him on.’

‘From what I remember, Master Dunmow did the urging.’

‘Yes,’ agreed Firethorn sadly. ‘Young Will was a most amenable host – and that’s something we’ve never had at this inn before. If the fellow perished in the fire, I grieve for him.’

‘And so should you, Master Marwood,’ said Nicholas. ‘It must have been a gruesome death. As for the candle, let’s suppose that it was indeed the villain. Who set it in the room?’

Firethorn pointed at Marwood. ‘He did, Nick.’

‘It all comes back to Westfield’s Men,’ insisted the landlord. ‘You’ve been nothing but trouble from the start. This is not the first attack you unleashed on my property. When you performed The Devil’s Ride Through London, you reduced the Queen’s Head to ashes.’

‘An unfortunate mishap,’ said Nicholas. ‘Sparks flew up by accident into your thatch. We suffered as much as you while the inn was being rebuilt. We had to leave London.’

‘The shame of it is that you ever came back.’

‘Without us,’ said Firethorn, inflating his barrel chest, ‘this place would be deserted. Westfield’s Men lend it true distinction.’

Marwood curled a lip. ‘True distinction, eh? Is that what you call it?’ he taunted. ‘I saw no true distinction when you played A Trick to Catch a Chaste Lady. You set off such an affray in my yard that the inn was almost pulled to pieces. I swore that you’d never perform here again after that.’

‘But wiser counsels prevailed,’ said Nicholas. ‘You allowed us back in time.’

‘And here is my reward.’ The landlord turned to survey the wreckage. ‘This is how I am repaid for my folly. Never again, sirs! You are banished from my inn forever. As for the fire,’ he went on, rounding on them, ‘I’ll seek compensation from you in the courts. I’ve been cruelly abused by Westfield’s Men.’

‘Then add this to the list of charges,’ Firethorn told him.

Drawing his sword, he used the flat of it to hit Marwood’s backside with a resounding thwack and sent him hopping across the yard with his buttocks in his hands. Firethorn laughed heartily but Nicholas was less amused.

‘Nothing was served by attacking the landlord,’ he said.

‘I had to do something to relieve my anger.’

‘He owns the Queen’s Head – we do not. The day will come when we’ll need to woo the testy fellow yet again. And we’ll not do it with a sword in our hands.’

‘No,’ said Firethorn, sheathing his weapon. ‘As ever, you will be our ambassador, Nick. Soothing words from you will win that unsightly gargoyle over again.’ He heaved a long sigh. ‘Though it will be many months before your embassy can begin.’ He remembered something. ‘Our patron must hear of this. Lord Westfield will be mightily distressed at the tidings.’

‘I’ll take on the office of telling him,’ volunteered Nicholas.

‘Ask him if he can aid us in some way.’

‘Not with money, I suspect. His debts mount with each year.’

‘You are behind the times, Nick. Our esteemed patron has had good fortune at last. His elder brother died earlier this year.’

‘I knew that.’

‘What you did not know is that he left him half his estate. Lord Westfield is transfigured. He has finally paid off his creditors.’

‘Cheering news,’ said Nicholas, ‘yet I look for no munificence from him. Unlike poor Will Dunmow, he is not given to charity. And talking of our erstwhile friend,’ he added considerately, ‘we must send word to his family of his unfortunate end. Though we had only the briefest acquaintance with him, it behoves us to act on his behalf. The landlord will certainly not do so.’

‘He’ll be too busy cooling his bum in a pail of water.’

‘Owen Elias spent the longest time with Master Dunmow. He’ll know where the young man lodged in London and what friends he may have in the city.’

‘It’s right to mourn for the dead but we must also have care for the living. Unless we can find somewhere else to play, the company will go into hibernation. A few of us will not fare too badly,’ said Firethorn, ‘because we have other irons in the fire, but most of the lads will suffer grievously. An actor without a stage is like a man without a woman, lacking in the one thing that allows him to prove his true worth.’ His gaze travelled around the yard. ‘Yesterday, we gave them The Italian Tragedy. This morning, we behold a real tragedy. Westfield’s Men have gone up in smoke.’

Nicholas was soulful. ‘That fate befell Will Dunmow,’ he noted. ‘We live to perform another day. For that, we owe a prayer of thanks.’

‘You are right, Nick.’ He doffed his hat and began to unbutton his doublet. ‘And I believe that we do have a duty to clear some of this rubbish away.’

Nicholas slipped off his cap and his buff jerkin. ‘I’ve sent George Dart to fetch the others,’ he said. ‘This is work for many hands. When he sees us helping here, the landlord’s heart may soften towards us.’ Firethorn gave a snort of derision. ‘And there will be compensation of a sort for you, Lawrence.’

‘Not from that death’s-head.’

‘I was thinking of your wife. Margery will be delighted to see more of her husband in the next few months.’

‘That’s a mixed blessing,’ said Firethorn, recalling his wife’s violent temper. ‘But not in your case, Nick. Your domestic life is less troubled than mine. If the company goes to sleep throughout the autumn, you will see a great deal of Anne. That must content you.’

‘Unhappily, no.’

‘Why not?’

‘Anne is planning another visit to Amsterdam.’

Located in Broad Street, the Dutch Church had once been part of an Augustinian monastery. After the dissolution, it had been granted to royal favourites of Henry VII, who had promptly shown their religious inclinations by using it as a stable. When his young son, Edward, succeeded to the throne, he gave the nave and aisles of the church to Protestant refugees, most of whom were Dutch or German, but they were not allowed to enjoy the gift for long. At the start of Queen Mary’s reign, that devout Roman Catholic gave the foreign congregation less than a month to leave and she shunned them thereafter. The accession of Queen Elizabeth saw the immediate restitution of a building that resumed its title of the Dutch Church, and acted as a central point for immigrant worshippers.

Anne Hendrik knew the place well and had attended many services there with her husband. A young Englishwoman with a quick brain, she had soon mastered Jacob Hendrik’s native language and learnt a great deal of German from him as well. A happy marriage was then cut short by the untimely death of the Dutchman, and his wife inherited the hat-making business that he had set up in Bankside. Showing a flair and acumen that she did not know she possessed, she managed the enterprise with considerable success. The reputation it achieved was not all Anne’s doing. Much of the credit had to go to Preben van Loew, her senior employee, a man whose talent and versatility brought in a stream of commissions.

It was the sober Dutchman who accompanied her on the long walk to church that morning. In a dangerous city, Anne was grateful for an escort, even one as taciturn as the emaciated old man.

‘It’s kind of you to come with me, Preben,’ she said.

‘I like to pay my respects as well.’

‘You were a good friend to Jacob.’

‘We grew up together,’ he said.

‘And fled to England together as well. It must have been a shock to you when he chose to marry someone like me.’

‘You were a good wife.’

‘I like to think so,’ said Anne with a nostalgic smile, ‘but you did not know that beforehand. You must have had serious doubts about me at first.’

The Dutchman was tactful. ‘I cannot remember.’

‘A wise answer.’

Side by side, they continued along the busy thoroughfare of Broad Street. They were making one of their regular journeys to the churchyard to visit the grave of Jacob Hendrik. It was always a sad occasion but there was some solace for Anne. Having paid her respects to her late husband, she would have an opportunity to call on the man who had replaced him in her life, Nicholas Bracewell, a dear friend who had begun as a lodger before finding himself her lover as well. Gracechurch Street was within easy walking distance of the Dutch Church. Ignorant of the tragedy that had befallen the Queen’s Head, Anne proposed to stop there in order to watch a little of the day’s rehearsal.

As she bore down on the church, however, her mind was filled with fond memories of Jacob Hendrik, a hard-working man who had been forced to settle south of the river because the trades guilds resolved to keep as many foreign rivals as they could out of the city. On arrival in England, her future husband had met with resentment and suspicion. When they reached their destination, Anne was suddenly reminded of what he had had to endure.

‘Not another one!’ said Preben van Loew with disgust.

‘Tear it down,’ she urged.

‘I wish to read it first.’

‘It’s the work of a twisted mind, Preben.’

‘A man should always know his enemy.’

The printed message was attached to the wall of the churchyard and it had a stark clarity. Both of them read the opening lines.

You strangers that inhabit in this land,

Note this same writing, do it understand;

Conceive it well for safeguard of your lives,

Your goods, your children and your dearest wives.

‘They still hate us,’ said the old man, shaking his head. ‘I have been here all these years and I am still a despised stranger.’

‘Not in my eyes.’

‘You are the exception.’

‘No, Preben,’ she said stoutly. ‘London is full of good, decent, tolerant citizens who would be repelled by this libel. Unfortunately, the city also harbours cruel and vicious men who envy the success that foreign tradesmen have.’

‘They are many in number.’

‘I do not believe that.’

‘They are,’ he said, rolling his eyes in despair. ‘Have you forgotten how easily the apprentices were incited to riot against us? We are despised and always will be.’

‘When I see such vile accusations, it makes me ashamed to call myself English. At times like this,’ said Anne, glancing into the churchyard, ‘I feel proud that I have strong Dutch connections. I feel sympathy for all who sought refuge here. You and Jacob had so much to bear when you left your own country.’

He shrugged. ‘It was no more than we expected.’

Wanting to turn away, she felt impelled to read more of the angry verse and saw a scathing attack on the government for allowing strangers to enter the realm.

With Spanish gold you are all infected

And with that gold our nobles wink at feats.

Nobles, say I? Nay, men to be rejected,

Upstarts that enjoy the noblest seats,

That wound their country’s breast for lucre’s sake,

And wrong our gracious Queen and subjects good

By letting strangers make our hearts to ache.

‘Take it down, Preben,’ she ordered. ‘Let us spare others the distress of having to read such hateful words.’

‘It is best to ignore it altogether.’

‘Remove it so that we may hand it over to a constable. It’s a malicious libel and the law protects you from such things.’

‘They still keep coming,’ he said dolefully.

‘Commissioners have been ordered to take the utmost pains to discover the author and publisher of these attacks. When they are caught, they will face a heavy punishment. Take it down,’ she repeated. ‘Nobody else can be insulted by it then.’

‘As you wish.’

‘And when you have done that, forget that you ever saw it.’

The Dutchman smiled. ‘I’ve already done so.’

Standing on tiptoe, he reached up to remove the verses from the wall. But they had a protector. No sooner did his hands touch the paper than a large stone was hurled from across the street. It struck his head with such force that his black skullcap was knocked off. Stunned by the blow, Preben van Loew fell to the ground with blood oozing from his head wound. Anne let out a gasp of alarm and bent down to help him. She did not see the figure that ran off quickly down a lane opposite. The libel on the wall of the Dutch Churchyard was no idle jest. Someone was ready to enforce the warning against strangers.

Chapter Two

They were all there. The entire cast of The Italian Tragedy had turned up at the Queen’s Head, along with the stagekeepers and the tireman, to help in the mammoth task of clearing away the wreckage. In a sense, they were also dismantling their own home so the work was additionally painful. Rank disappeared. From the actor-manager down to the humblest hired man in the company, everyone did his share. The only actor who refused to dirty his hands, or to risk staining his exquisite attire by struggling among the filthy ruins, was Barnaby Gill, a brilliant clown on stage but a morose and egotistical man when he stepped off it. Since it was beneath his dignity to take part in physical labour, he simply watched sourly from the other side of the yard and deplored the fact that he would be unable to display his histrionic skills there again for a very long time.

There was a crowning irony. Fire had robbed them of their playhouse yet they had to engage the self-same thief to dispose of the booty. Beams, floorboards and furniture beyond recall were tossed on to a bonfire in the middle of the yard. Bricks, plaster and broken tiles were wheeled away in wooden barrows. Bed linen had been burnt to extinction. Pewter tankards and utensils had melted in the heat of the furnace. Some things could be saved for re-use but most had perished during the night. There were consolations. The fire had not consumed the Queen’s Head in its entirety and, because there had been no wind, sparks had not been carried to any of the adjacent properties.

It was Nicholas Bracewell who discovered the body. As he scooped up another armful of shattered tiles, he saw a foot protruding from the debris. It was bare and discoloured. Since the fire had only claimed one victim, the foot simply had to belong to Will Dunmow. He was buried beneath some badly-charred roof timbers.

‘I’ve found him,’ said Nicholas, throwing the tiles aside. ‘Give me a hand, Owen.’

‘Gladly,’ offered Owen Elias, scampering across to him. ‘Are you sure that it’s him?’

‘Who else can it be?’ Taking a firm grasp, they moved the first heavy oak beam between them. ‘The fire started in his bedchamber and that would have been directly above this spot.’

‘Poor Will! He had no chance.’

‘The landlord blames you for leaving a lighted candle there.’

Elias was roused. ‘Then he needs to be told the truth,’ he said indignantly. ‘I made a point of snuffing out the candle before we left. You can ask James. He’ll bear witness.’

‘I take your word for it, Owen,’ said Nicholas, ‘but that raises a question. If a candle did not cause the fire, then what did?’

‘Who knows?’

Taking hold of the next beam, they heaved it aside to expose the upper half of the corpse. It was a grisly sight. Scorched and distorted, Will Dunmow’s handsome face was a grotesque mask. His hair had burnt down to the skull, his eyebrows had been singed and both nose and jaw had been broken by the impact of the falling timber. Every shred of clothing had been burnt off his body, leaving his flesh black and mutilated. Nicholas felt a surge of compassion.

‘His own mother would not be able to recognise him,’ he said. ‘I thank heaven that she did not see him in this condition.’ He turned to Elias who was staring in horror at the corpse. The Welshman was visibly shaken. ‘What ails you, Owen?’

‘It was true, Nick – hideously true.’

‘True?’

‘What I said to James as we lay him on his bed last night. I said that Will would sleep until doomsday.’ Elias bit his lip. ‘I did not realise that doomsday would come so soon for him.’

‘How could you?’

‘I feel so guilty.’

‘You were not to blame.’

‘It was almost as if I prophesied his death.’

‘That’s a foolish thought. This was none of your doing.’ He became aware of the small crowd that had gathered to look at the body with morbid curiosity. Nicholas waved them away. ‘Back to your work, lads. Will Dunmow was kind to us. Do not stare so as if he were a species of monstrosity. Grant him some dignity.’ The others began to drift away. ‘I can manage here, Owen,’ he went on. ‘Fetch something to cover him from prying eyes.’

‘Yes, Nick.’

The Welshman went off and left Nicholas to remove the rest of the debris that covered the dead man. He did so with great care, averting his eyes from the crushed legs that came into view. Pity welled up in him once more. In the course of his life, Nicholas had seen death in many guises but none so shocking and repulsive as the one that now confronted him. Will Dunmow had not merely been killed. He had been deformed and degraded. By the time the book holder had liberated the body completely, Elias returned with a large white sheet that he had taken from the room where they kept their wardrobe. It was laid over the corpse with reverence then the two of them lifted Will Dunmow up and carried him to a cart that stood nearby. They lowered him gently into it.

‘There’ll have to be an inquest,’ said Nicholas.

‘I’ll see the body delivered to the coroner.’

‘Thank you, Owen.’

‘Then I’ll do what I can to track down the house where Will was staying while he was in London. He told me that it was in Silver Street,’ explained Elias, ‘and belonged to a friend. I’ll find him if I have to knock on every door.’

‘Save yourself the trouble. I think this friend will come to us. He must have known that Will was at the play yesterday afternoon. Since his lodger did not return last night, the friend will want to know why. In time, he’ll turn up at the Queen’s Head.’

‘Then he’ll be met with dreadful news.’

‘Yes,’ said Nicholas. ‘And the worst part of it is that we cannot even tell him how the fire started.’

‘I could hazard a guess.’

‘Could you?’

‘I’ve been thinking about what he said,’ remembered Elias. ‘When we carried him to his chamber, he kept calling for a bottle of sack. Will said that he’d like to drink some more and smoke a pipe of tobacco before he went to sleep.’

‘A pipe?’

‘That might be the explanation, Nick.’

‘Indeed, it might.’

‘How he managed to light it, God knows, for he was as drunk as a lord. As soon as his head touched the pillow, he was asleep.’

‘He must have come awake again,’ decided Nicholas, ‘and tried to smoke a pipe. Will Dunmow would not be the first man to doze off and start a fire unwittingly with burning tobacco.’

‘An expensive mistake. He paid for it with his life.’

‘Take him to the coroner, Owen. Describe what happened here and tell him that we know precious little about Will Dunmow apart from his name and his generosity. I’ll carry on here.’

‘Not for a while, Nick,’ said Elias as he saw two figures walking across the yard. ‘You have company.’

Nicholas looked up to see Anne Hendrik and Preben van Loew heading towards him. They were looking around with dismay. Elias stayed long enough to exchange greetings with them before driving the body away in the cart. Anne was horrified by the amount of damage.

‘What happened?’ she asked.

‘We are not certain,’ replied Nicholas, ‘and never will be, alas. But we think someone started the fire when he fell asleep with a pipe of tobacco still burning. He died in the blaze. Owen is just taking him to the coroner.’

‘We expected to find you rehearsing today’s play.’

‘Out of the question, Anne.’

‘So I see.’

‘It will be next spring at least before we return to the Queen’s Head. The landlord would rather that we never came back.’ He glanced at the bandaging around the old Dutchman’s head. ‘But enough of our troubles. Preben seems to have encountered some of his own. I thought you both went to the churchyard this morning.’

‘We did, Nicholas,’ he said somnolently. ‘There was another vicious attack on strangers, I fear.’

‘It was on the wall,’ said Anne. ‘When Preben took it down, he was hit on the head by a stone. We did not see who threw it. It was a bad wound. We had to find a surgeon to dress it.’

Nicholas was sympathetic. ‘I’m sorry to hear that. Another libel, you say? That’s bad. Let’s stand aside,’ he said, moving them away from the noise of the clearance work behind him. ‘Now – tell me all.’

Lord Westfield gazed in wonder at the miniature then let out a cry of delight. Holding the portrait to his lips, he placed a gentle kiss on it.

‘I love her already!’ he announced. ‘What is her name?’

‘Sigbrit, my lord,’ said his companion. ‘Sigbrit Olsen.’

‘A beautiful name for a beautiful lady.’

‘That miniature was painted only last year.’

‘And is she as comely in the flesh?’

‘I’ve every reason to think so,’ said Rolfe Harling. ‘I’ve not had the pleasure of meeting her yet but, when I spoke with her uncle in Copenhagen, he could not praise her enough. He described his niece as a jewel among women.’

‘I can see that, Rolfe. The creature dazzles.’

Lord Westfield was so enraptured by the portrait that he could not take his eyes off it. Framed by silken blonde hair, Sigbrit Olsen had a face that combined beauty, dignity and youthfulness. Her skin seemed to glow. Lord Westfield pressed for details.

‘How old is she?’

‘Twenty-two.’

‘Less than half my age.’

‘Such a wife would take years off you, my lord.’

‘That’s my hope. Has she been married?’

‘Only once,’ stressed Harling, ‘and her husband died in an accident soon after the wedding. There was no issue. At first, she was overcome with grief. After a decent interval of mourning, however, she is now ready to start her life afresh and she prefers to do it abroad. Denmark has too many unhappy memories for her.’

‘Then I must take her away from them.’

‘That would be viewed as a blessing, my lord.’

‘By me as well as by her.’

He kissed the portrait again. Lord Westfield was a short, plump man of middle years with a reddish complexion lighting up a round, pleasant face. Thanks to a skilful tailor, his slashed doublet of blue and red gave him a podgy elegance and his breeches cunningly concealed his paunch. He had been married twice before but had outlived both of his wives. Though he led a sybaritic existence that involved the pursuit of a number of gorgeous young ladies, he had now decided that it might be time to wed for the third time.

‘How do you think that Sigbrit would look on my arm, Rolfe?’

‘You will make a handsome couple, my lord,’ flattered Harling.

‘She would be the envy of all my friends.’

‘That thought was in my mind when I chose her.’

‘You have done well, Rolfe.’

‘Thank you,’ said Harling with an obsequious smile. ‘It has taken time, I know, but a decision like that could not be rushed. I did not wish to commit you until I was absolutely convinced.’

‘I would have preferred it if you had actually seen Sigbrit.’

‘So would I, my lord, but she was visiting relatives in Sweden when I was there. Her uncle is eminently reliable, I assure you, and I’ve had good reports of the lady from others. Until her marriage, she was a lady-in-waiting at court.’

‘That, in itself, is recommendation enough.’

‘The Dowager Queen likes to surround herself with beauty.’

Lord Westfield beamed. ‘And so do I, Rolfe.’

They were in the house that Lord Westfield used when he was staying in the city. His estates were in Hertfordshire, north of St Albans, close enough to London to allow easy access to and fro yet far enough away to escape the stench and the frequent outbreaks of plague that afflicted the capital. He had been waiting for weeks for the return of Rolfe Harling. Since his reputation for promiscuity was too well-known in England, Lord Westfield had chosen to look elsewhere for a wife and Harling had been dispatched to find a suitable partner for him, searching, as he did, through three other countries before settling on the woman whose portrait he had brought back.

Rolfe Harling was a tall, thin individual in his thirties with long, dark hair and a neat beard. He wore smart but sober apparel and, with his scholarly hunch and prominent brow, he conveyed an impression of intelligence. The fact that he spoke four languages had made him an ideal person for the task in hand.

‘Do you ever regret leaving academic life?’ asked Lord Westfield.

‘Not at all, my lord. Oxford has its appeal but it can seem very parochial at times. Travel has taught me far more than I could learn from the contents of any library.’

‘That depends on where you travel.’

‘Quite so,’ said Harling. ‘As an Englishman, there are some countries that I have no desire to visit – Spain, for instance. I would never have dared to foist a wife from that accursed nation upon you. Spain is our enemy, Denmark our friend.’

‘And likely to remain so.’

‘That, too, was taken into consideration.’

‘You have been diligent on my behalf,’ said Lord Westfield, ‘and I thank you for it. My brother’s death was a bitter blow but it brought a welcome change of fortune to me. Hitherto, I baulked at the idea of asking a woman to share my poverty with me. Now that I can afford to marry again, I will do so in style.’

‘Sigbrit Olsen will not disappoint you. Through her uncle, she makes only one request, and that is for the wedding to be on Danish soil. I was certain that you would abide by that condition.’

‘Gladly. Let her nominate the place.’

‘She has already done so.’

‘Copenhagen?’

‘No, my lord,’ said Harling. ‘The lady prefers her home town. In her native tongue, it is called Helsingor.’

‘And what do we call it in English?’

‘Elsinore.’

Preben van Loew was a very private man who had remained single by choice because of his excessive shyness and because of a lurking fear of the opposite sex. He liked and respected Anne Hendrik, but even she was not allowed to get too close to him. When they returned to her house in Bankside, therefore, he refused her offer to examine the wound and dress it with fresh bandaging. Still in pain, he wanted to get back to his work in the premises adjoining her house in order to put the incident at the Dutch Churchyard out of his mind.

‘You are not well enough to go back to work,’ Anne said.

‘I am fully recovered now,’ he told her.

‘Your face belies it, Preben. That stone was thrown hard.’

He gave a pale smile. ‘You do not need to remind me.’

‘If you feel the slightest discomfort, you have my permission to leave at once. Do not tax yourself. Every commission we have has been finished ahead of time. You are under no compulsion.’

‘Thank you.’

‘And when you do want the dressing changed, come to me.’

‘I will,’ he said.

But she knew that he was unlikely to do so. He had such a strong sense of independence that he hated to rely on anyone else, especially a woman. Preben van Loew was an odd character. When he had been struck on the head, he was less concerned with the searing agony than with the embarrassment he felt at having been attacked in Anne’s presence. Having set out that morning as her protector, it was he who now needed protection. It was an affront to his pride.

‘Do not tell them about this in Amsterdam,’ he requested.

‘But they will all ask after you, Preben.’

‘Tell them that I am well.’

‘But you are not,’ she said.

‘I want them to hear only good news about me. If they know about the attack, my family and friends will only worry about me.’

‘And so they should.’

‘Spare them the anguish,’ he said. ‘Tell them the truth – that I live a happy life among people I admire, and do a job that I have always loved. I want no fuss to be made of me, Anne.’

Anne became reflective. ‘You sound like Jacob,’ she recalled. ‘During his last illness, when he lacked the strength even to get out of bed on his own, he kept telling me not to cosset him. He hated to put me to the slightest trouble. I was his wife yet he would still not let me pamper him. Can you understand why?’

‘Very easily.’

‘Then you and he are two of a kind.’ She thought about the narrow, dedicated, industrious, almost secret existence that he led and she changed her mind. ‘Well, perhaps not. As for your injury …’

‘These things happen. We just have to accept that.’

‘Well, I’ll not accept it,’ she said with spirit, ‘and neither will Nick. You saw how angry he was when we told him about it.’

‘But there was no need to do so, Anne. It’s far better to remain silent. All that I had was a bang on the head. Think of the problems that Nicholas is facing after that fire,’ he said. ‘You should not have bothered him with this scratch that I picked up.’

‘It was much more than a scratch, Preben.’

‘It will heal in time.’

‘Someone deserves to be punished.’

‘We do not know who he was.’

‘Nick will find out.’

‘How can he?’ asked the old man. ‘He was not even there.’

‘Perhaps not, but he cares for you, Preben. That’s why he took such an interest in the case.’

‘I’d rather he forget it altogether.’

‘Then you do not know Nick Bracewell,’ she said proudly. ‘If his friends are hurt, he’s not one to stand idly by. You may choose to forget the outrage but he will not. Sooner or later, Nick will make someone pay for it. You will be avenged.’

After toiling away for most of the morning with the others, Nicholas Bracewell left the Queen’s Head to call on their patron. Lord Westfield liked to be kept informed about his troupe and this latest news would brook no delay. Having cleaned himself up as best he could, therefore, Nicholas made his way to the grand house he had often visited in the past. In times of crisis for Westfield’s Men – and they seemed to come around with increasing regularity – the book holder always acted as an intercessory between the company and its epicurean patron. He had far more tact than Lawrence Firethorn and none of the actor’s booming self-importance. As a result of Nicholas’s long association with the company, Lord Westfield appreciated the book holder’s true worth. It made him the ideal messenger.

The servant who admitted him to the house was not impressed with his appearance but, as soon as he gave the name of the visitor to his master, he was told to bring him into the parlour at once. Nicholas was accordingly ushered into the room and found Lord Westfield, sitting in a chair, scrutinising a miniature that he held in his palm. It was moments before the patron looked up at him.

‘Nicholas,’ he said with unfeigned cordiality. ‘It is good to see you again, my friend.’

‘Thank you, my lord.’

‘What brings you to my house this time?’

‘Sad tidings.’

‘Oh?’

‘There has been a fire at the Queen’s Head.’

‘A serious one?’

‘Serious enough,’ said Nicholas.

He gave Lord Westfield a detailed account of what had happened, speculating on the probable cause of the blaze and emphasising the dire consequences for the company. To Nicholas’s consternation, their patron was only half-listening and he appeared to be less interested in the fate of the troupe that bore his name than he was in the portrait at which he kept glancing. When he had finished his tale, the visitor had to wait a full minute before Lord Westfield even deigned to glance up at him.

‘Is that all, Nicholas?’ he asked.

‘Yes, my lord.’

‘Sad tidings, indeed.’

‘We have been wiped completely from the stage.’

‘And you believe this man started the fire?’

‘It is only a conjecture,’ admitted Nicholas.

‘Then it could just as easily have been arson.’

‘Oh, no, my lord.’

‘But we have jealous rivals,’ Lord Westfield reminded him. ‘They have often tried to bring us down before. Someone employed by Banbury’s Men could have burnt us out of our home.’

‘There is no suggestion of that.’

‘But it is a possibility.’

‘No, my lord.’

‘Why not?’