Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

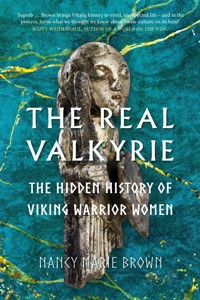

'As heroes we were widely known – with keen spears we cut blood from bone.' In 2017, DNA tests revealed to the collective shock of many scholars that a Viking warrior in a high-status grave in Birka, Sweden, was actually a woman.The Real Valkyrie weaves together archaeology, history and literature to reinvent her life and times, showing that Viking women had more power and agency than historians have imagined. Nancy Marie Brown links the Birka warrior, whom she names Hervor, to Viking trading towns and to their great trade route east to Byzantium and beyond. She imagines Hervor's adventures intersecting with larger-than-life but real women, including Queen Gunnhild Mother-of-Kings, the Viking leader known as the Red Girl, and Queen Olga of Kyiv. Hervor's short, dramatic life shows that much of what we have taken as truth about women in the Viking Age is based not on data but on nineteenth-century Victorian biases. Rather than holding the household keys, Viking women in history, the sagas, poetry and myth carry weapons. In this compelling narrative, Brown brings the world of those valkyries and shield-maids to vivid life.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 596

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE REALVALKYRIE

ALSO BY NANCY MARIE BROWN

Ivory Vikings

Song of the Vikings

The Far Traveler

First published in the United States by St. Martin’s Press, an imprint of St. Martin’s Publishing Group

This edition published 2021

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Nancy Marie Brown, 2021

The right of Nancy Marie Brown to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1998.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9842 0

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

For my sisters

CONTENTS

A Note on Language

Introduction: The Valkyrie’s Grave

1: Hervor’s Song

2: Gunnhild Mother-of-Kings

3: The Town Beneath the Shining Hall

4: Little “Hel-skins”

5: Queen Asa’s Revenge

6: The Winter Nights Feast

7: The Valkyries’ Task

8: The Feud

9: The Queen of Orkney

10: The Tragedy of Brynhild

11: Shield-Maids

12: The Red Girl

13: Slave Girls

14: The Slave Route to Birka

15: Red Earth

16: A Birka Warrior

17: The Kaftan

18: The East Way

19: At Linda’s Stone

20: “Gerzkr” Caps

21: Queen Olga’s Revenge

22: Death of a Valkyrie

Acknowledgments

List of Illustrations

Further Reading

Notes

A NOTE ON LANGUAGE

I have standardized and Anglicized the spelling of foreign words and names (even within quotations) throughout this book, dropping all accents and diacritical marks. To make my speculations about the tenth century clear, I use quotation marks only for direct references to a text, medieval or modern; these are cited in the endnotes.

The holes in the record present one hazard, what we have constructed around them another.

—Stacy Schiff, Cleopatra

Objectivity is not a possibility. Our definition of the past is part of the way we define ourselves.

—Anthony Faulkes, “The Viking Mind, or In Pursuit of the Viking,” Saga Book XXXI

INTRODUCTION

THE VALKYRIE’S GRAVE

All I have are her bones. I don’t know her name, or precisely where or when she was born. I don’t know how she died, though bones often do betray such secrets. All I have are her bones, now boxed and stored in a museum in Sweden, bones gathered by an archaeologist in 1878 from a grave beside a hillfort overlooking the Viking town of Birka, where she was buried in the mid-tenth century in a spacious, wood-lined pit.

To tell her story, all I have are her bones—and what was unearthed with her: an axe blade, two spearheads, a two-edged sword, a clutch of arrows, their shafts embellished with silver thread, a long sax-knife in a bronze-ringed sheath, iron bosses for two round shields, a short-bladed knife, a whetstone, a set of game pieces (bundled in her lap), a large bronze bowl (much repaired), a comb, a snip of a silver coin, three traders’ weights, two stirrups, two bridles’ bits, and spikes to ride a horse on the ice, along with the bones of two horses, a stallion and a mare. Of her clothing all that remains are an iron cloak pin, a filigreed silver cone, four baubles or buttons of coiled silver wire, strips of silk embroidered with silver, and a scattering of mirrored sequins.

Until 2017, when DNA tests proved the bones were female, this grave, numbered Bj581, was held up as the classic Viking warrior’s grave. “The position of the skeleton,” wrote a Swedish archaeologist in 1966, “gave the impression that he had been sitting in the grave, rather than laid out. . . . The equipment indicates that this is a warrior’s grave rather than that of a merchant. . . . The date of a silver coin, found underneath the skeleton of the dead man, provides a fairly good idea of the date of the grave: 913–980 A.D.”

The implications of the “dead man” turning into a dead woman dazzle me. They ignite my imagination. A burial with weapons and horses, an archaeologist claimed as late as 2008, used “a widely recognised symbolic language of lordship, one that was unquestionably masculine.” To assume all such “weapons graves” are male now seems to me to be a mistake—one that has skewed our image of the Viking Age. How does history change if we turn that assumption on its head?

There are other ways to interpret the grave, other ways to explain a female body buried with weapons. But the simplest seems to me the most likely. Defending their findings in 2019, the team that tested her DNA said Bj581 “suggests to us that at least one Viking Age woman adopted a professional warrior lifestyle.” They added, “We would be very surprised if she was alone in the Viking world.”

A Viking is a raider from the sea. During the Viking Age, roughly 750 to 1050, Europe was plagued by such pirates in their swift dragonships. The Vikings were traders and explorers, too. They were farmers, poets, engineers, artists—but their place in history was carved by their swords. “From the fury of the Northmen, O Lord, deliver us!” wrote a French monk around the year 900. They “ransacked and despoiled, massacred, and burned and ravaged,” wrote another, who witnessed the Viking attack on Paris in 885. In Ireland in the mid-800s, a monk praised the safety of a storm:

Bitter is the wind tonight,

White the tresses of the sea;

I have no fear the Viking hordes

Will sail the seas on such a night.

Archaeology backs up the Vikings’ violent image: Across Northern Europe, from Russia in the east to Iceland in the west, Vikings are found buried with swords. Three thousand Viking swords are known from Norway alone. Assuming all sword-bearers are male, writers limn the Viking Age as hypermasculine: a time when “shiploads of these huge and brawny men would suddenly appear out of the sea mists. They would pillage at will, mercilessly cutting down all opposition.”

Let’s set aside, for a moment, the idea that mercilessness is a masculine trait. How does an archaeologist know a buried Viking is male? The bones found beside the buried swords, if any, are degraded. Sexing them by their robustness or by the shape of the skull or pelvis is often not possible—and is always open to interpretation. There’s no internationally agreed-upon definition of “robust”; there’s no absolute scientific scale for pelvic structure. DNA sexing is difficult and expensive and, so, rarely done. Instead, “sexing by metal” has been standard procedure since 1837, before archaeology as a science even existed. Graves with weapons—even cremation graves in which the bones have been crushed after burning—are catalogued as male; those with jewelry are female. The thirty-some Viking graves in which slender, female-looking bones were unearthed beside weapons are ignored as “noise in the data.”

The result? Historians and novelists write confidently of ships carrying only “huge and brawny men.” Museum designers and filmmakers and Viking reenactors re-create in exquisite detail a male-dominated Viking world. When we hear the word “Viking,” we imagine a well-armed man.

Yet most people who died in the Viking Age were buried with nothing that will sex them. Even the elite, the people whose graves announce their high status, often hide their sexual identity, as if their gender mattered not at all. Half of the elite burials in some Viking graveyards contain neither weapons nor jewelry. Their grave goods, though rich, are horses and boats and knives and tools: things that cannot be gendered.

And now, in Birka grave Bj581, we have a woman buried as a Viking warrior. What does her grave tell us? That we don’t know the Vikings as well as we thought.

In December 2012, a man using a metal detector near the village of Harby in Denmark found a small face peering up at him from a lump of frozen dirt. His find, cleaned up, was an intricately detailed figurine of gilded silver, about an inch tall, in the shape of a woman with long hair twisted into a ponytail. She carries a sword and shield.

I know of seven flat metal images of a woman with weapons, and seventeen showing a shield-carrier facing a horse rider armed with sword and spear, both perhaps female. These images were found in Denmark, England, Germany, and Poland. Similar images of women with weapons, fashioned from thread or carved in stone, come from Norway, Sweden, and Russia.

A three-dimensional Viking warrior, just over an inch tall, from Harby, Denmark.

The figurine from Harby is the first three-dimensional portrayal to appear. Like the others, she is dismissed as a “valkyrie.” By that the experts mean she is not real.

The Old Norse word valkyrja combines valr, “corpse,” and kjósa, “to choose.” The standard definition comes from Snorri Sturluson. Writing in Iceland between 1220 and 1241, this Christian-educated lawyer, politician, and poet described valkyries as pagan battle-goddesses with shield and sword (or spear) who ferried dead heroes to Valhalla, the otherworldly feast hall of the god Odin, and there served them celebratory cups of mead. Trusting Snorri (who was well known, in his lifetime, for being untrustworthy), modern scholars classify valkyries as “mythological.” They are “firmly supernatural” or, at most, “semi-human.”

Why, when we see the Harby figurine, do we not assume, instead, that it depicts an actual woman—that carrying a sword and shield was “a perfectly ordinary aspect of a woman’s life” in the Viking Age? A 2013 museum exhibition in Copenhagen did suggest that—and sparked a storm of rebuttal. The argument devolved to one point: Said a specialist on women of the Viking Age, “We know that warriors were men.”

How do we know that?

Norse culture in the Viking Age, I was taught, was divided along strict gender lines. I described it that way myself in my previous books. The woman ruled innan stokks, “inside the threshold,” where she held considerable power, for she was in charge of clothing and food. In lands where winter lasts ten months and the growing season two, the housewife decided who froze and who starved. The larger the household, the more complex her job. Keeping house for a chieftain with eighty retainers, as well as family and servants, she was the CEO of a small business.

But for all that, the man held the “dominant role in all walks of life,” I was taught. His duties began at the threshold of the house and expanded outward. His was the world of public affairs, of “decisions affecting the community at large.” He was the trader, the traveler, the warrior. His symbol was the sword.

The woman’s role, in turn, was symbolized by the keys she carried at her belt.

Except she didn’t.

Our picture of everyday life in the Viking Age is largely drawn from later written sources, from laws, poems, and the long prose Icelandic sagas, all of which survive only in manuscripts from the 1200s or later—more than two hundred years after the people of the North converted to Christianity and their culture radically changed. There are more than 140 Icelandic sagas; only one, recounting a feud from 1242, refers to a housewife’s keys. A Danish marriage law from 1241 says that a bride is given to her husband “for honor and as wife, sharing his bed, for lock and keys, and for right of inheritance of a third of the property.” A bawdy poem, in an Icelandic manuscript dated after 1270, describes the hypermasculine thunder god, Thor, disguised as a bride with a ring of keys at his belt.

These three are the only mentions of housewives with keys I can come up with: two women and a man in drag. They might reflect a pagan truth from before the year 1000. They might equally reflect the values of the medieval Christian world in which they were written. No one can say for sure.

Women with weapons appear in these same texts much more frequently than women with keys: I can name twenty warrior women from sagas and histories, another fifty-three in poems and myths. The earliest Icelandic lawbook (dated 1260 to 1280) considers women with weapons a threat to society—which implies they existed. You don’t write laws to control myths.

Why then did keys become the symbol of Viking womanhood? Because our image of the Viking world took shape in the nineteenth century. Keys reflect the values of Victorian society, when upper-class women were confined to the home and told to concern themselves only with children, church, and kitchen. The iconic Viking housewife with her keys first appeared in a Swedish history book in the 1860s, replacing an earlier historical portrait of Viking women who were strikingly equal to Viking men. The Victorian version of Viking history has been presented ever since as truth—but it is only one interpretation.

Surely archaeology backs up the image of the Viking housewife with her keys, doesn’t it?

It does not.

Keys have been found in some Viking women’s graves. But they are not common, nowhere near as common as the symbol chosen for Viking men, the sword. Against the three thousand swords from Viking Age Norway, a Norwegian archaeologist in 2015 sets only 143 keys, half of which were found in men’s graves. An archaeologist in Denmark in 2011 found that only nine out of 102 female graves she studied contained keys. Calling keys the symbol of a Viking woman’s status, these researchers say, is “an archaeological misinterpretation,” “a mistake,” “a myth”—and a dangerous one.

By accepting the Victorian stereotype of men with swords and women with keys, we legitimize the idea that women should stay at home.

We reduce the role models for every modern girl who visits a museum or reads a history book.

We make it hard to even imagine a Viking warrior woman like the one buried in Birka grave Bj581.

Viking society was not like Victorian society. It was not like our own. It was a martial society, in which vengeance was praised and war was glorified. An insult to one’s honor—as slight as a nasty poem, as serious as the killing of kinsfolk—was repaid with violence or, at least, by the threat of violence until blood money was paid. Of heroes it’s said they “fled not,” but fought as long as they could hold a weapon. Fearlessness was the highest virtue. Death was met with laughter. The winner in any conflict was the one who wouldn’t give up.

No one is immune to violence in such a society. No one is a noncombatant, no one is safe, inside the threshold or out.

In medieval texts depicting this martial Viking society, women “do battle in the forefront of the most valiant warriors.” “Like a son,” they avenge the killing of their kinsmen. They kill berserks, break shields, kill one king and help another. They say, “As heroes we were widely known—with keen spears we cut blood from bone. Our blades were red.”

These women are called trolls or giants, valkyries, or shield-maids—but not shield-maidens, as in many modern translations. The Old Norse word skjaldmær joins “shield” to “girl,” “daughter,” or “virgin.” Another term for a warrior woman, skjaldkona, “shield-woman,” makes it clear that sexual experience has nothing to do with warrior status. The comparable word for male warriors is drengr, literally “boy” or “lad” (which originally meant one who is “led by a leader”). Drengr is occasionally applied to women, too. The issue is not sex, but status. These warriors are not householders. They have no economic responsibilities. They have no obligations except to their war leader. They are professional fighters.

The warrior women in these texts are portrayed as human, semi-human, or supernatural. But so are their male counterparts: the berserks (or “bear-shirts”), whom iron cannot bite, the half trolls and dragon-slayers, the shape-shifters who turn into wolves. Male or female, many warriors in Icelandic sagas and Old Norse poetry talk to gods (or birds), use magic, have inordinate luck or strength that increases after sunset, are matchless athletes, outlive a normal life span, and serve mead to heroes in Valhalla. Only the females are explained away by modern scholars as fantasy or wish fulfillment. Only the females are considered as fabulous as dragons.

The Victorian stereotype blinds us.

We need to clear our eyes. The sources depicting Viking women with weapons—the Christian-era texts, the images, the ambiguous burials, and stray archaeological finds—are the same sources depicting Viking men. To write about the Viking Age at all means to connect the dots. To make educated guesses. To interpret and to speculate.

Reading itself is a form of interpretation. Words like menn in Old Norse, manna in Old English, and homines in Latin have been casually translated for hundreds of years as “men”—but they also mean “people,” no genders implied. When these menn are warriors, translators have assumed they were all masculine. Yet Old Norse can be gender-specific when it matters. When a warrior using the masculine name Hervard killed a man in a king’s hall, in one saga, the king’s warriors egged one another on to go after him. Then the king spoke up, calling out information they’d apparently missed: “I think he is a kvennmann,” the king said. “I think, moreover, that with the weapon she has, each of you would find it dearly bought to take her life.” As the king’s shift in pronouns reveals, kvennmann means “female person”; kvenn is our word “queen.” Its opposite, karlmann, “male person,” is also used in the sagas—when gender matters.

“Was femaleness any more decisive,” mused one saga scholar as long ago as 1993, “in setting parameters on individual behavior than were wealth, prestige, marital status, or just plain personality and ambition?”

I think it was not.

Mercilessness is not a masculine trait.

What would the Viking world look like if we revised our assumptions? What would it look like if roles were assigned, not according to Victorian concepts of male versus female, but based on ambition, ability, family ties, and wealth?

In this book, inspired by a warrior woman’s bones, I reread the texts and reexamine the archaeological finds with that question in mind. I use what my research uncovers to re-create the world of one warrior woman in the Viking Age.

I don’t know her name, so I’ve given her one: I call her Hervor. Other famous skeletons have names. There’s Lucy the Australopithecus, named for a Beatles song, and Otzi the Iceman, named for the valley he was found in.

I could have named her Lagertha, after the shield-maid who Saxo Grammaticus, writing his Gesta Danorum (or History of the Danes) in Latin around the year 1200, said “would do battle in the forefront of the most valiant warriors.” But Lagertha has already been brought to life by the actress and martial artist Katheryn Winnick in the History Channel television series Vikings. I could call her Brynhild, Geirvifa, Svava, Mist, Thogn, or Sigrun, the names of valkyries in sagas and poems, names that mean Bright Battle, Spear Wife, Sleep Maker, Fog of War, Silence of Death, or Victory Sign. But I call her Hervor, after the warrior woman in the classic Old Norse poem Hervor’s Song. Her means “battle.” Vör means “aware.” Hervor, then, means Aware of Battle, Warrior Woman.

Who was this Hervor, buried in grave Bj581 outside the Swedish town of Birka sometime between 913 and 980? What might her life have been like? To tell her story, all I have are her bones, but bones can be eloquent. If complete, a skeleton speaks not only of its sex; it whispers of its life and death. Diseases—if they don’t kill quickly—can mark bones, as can repeated motions like rowing or riding or stringing a bow. Injuries and accidents are recorded in bones.

Yet to read cut marks as killing blows—the edges of the wound “sharp and splintery,” not the smooth, rounded traces of earlier, healed injuries—the surface of the bones must be pristine. Bones buried for a thousand-plus years are rarely pristine. Like wood, cloth, leather, food, and other biodegradable objects placed in Viking Age graves, bodies rot—that’s the point of burial, after all, to return to earth. It takes less than twenty-five years (sometimes much less) for a buried body to be reduced to bones. How long those bones last depends on the chemistry of the soil they’re set in.

Hervor’s bones, the bones in grave Bj581, are too degraded for any signs of action, illness, or battle trauma to be seen. Bone preservation at Birka is generally poor. The soil is too acidic. The mineral constituent of the bones simply breaks down into calcium and phosphorus salts that leach away. Microbes and fungi carve fissures and tunnels. The bones break into bits and dissolve into dust.

In many of Birka’s eleven hundred excavated graves, all that remained by the time they were opened in the late 1800s were loose teeth. In Bj581, by contrast, were bones from all parts of Hervor’s body. Compared to her neighbors, she is remarkably well preserved. She is one of the few Birka skeletons to have a complete backbone. She has two ribs, bones from each arm and each leg, part of her pelvis, and her lower jaw. Her bones are characteristically female—as osteologists pointed out at least twice (and were ignored) before the DNA test confirmed her sex.

When she was dug up in 1878, her skull was also recovered; it has since gone missing. Anatomical collections were in fashion in the late 1800s, and archaeologists often lent or traded bones with their friends. Skulls were particularly popular: Their shape was thought to reflect race, intelligence, and even criminal tendencies. Archaeologists still use the shape of the skull to sex a skeleton. Women’s skulls are thought to be smoother and more rounded, while men’s have a more prominent brow ridge and a more muscular jaw, though hormone fluxes can cause older women’s skulls to resemble men’s.

DNA sexing leaves less room for doubt. If DNA can be extracted at all, it can usually be sexed. In Hervor’s case, university researchers from Stockholm and Uppsala extracted DNA from one tooth and one arm bone recovered from grave Bj581. They sequenced the DNA and searched for Y chromosomes, the genetic signal of maleness. Their results fell far to the female end of the spectrum.

The mature appearance of certain bones and the level of wear on her molars say Hervor was at least thirty when she died—she could have been as old as forty. Her bones tell us, too, that Hervor ate well all her life, which means she came from a rich family, if not a royal one. At over five foot seven, she was taller than most people around her: Five foot five was the average man’s height in tenth-century Scandinavia; King Gorm the Old, who ruled Denmark during Hervor’s lifetime, was considered tall at five foot eight.

The chemistry of her teeth tells us Hervor was not a native of Birka, where she was buried, on an island in Lake Malaren a short boat ride from present-day Stockholm. She came from away. As teeth develop, they pick up isotopes of strontium (which mimics calcium) from the local water. The strontium signature of a tooth will thus match that of the bedrock where the child lived when the tooth’s enamel formed. Hervor’s first molars (mineralized before she was three) reveal that she was born somewhere in the western part of the Viking world, in what is now southern Sweden or Norway. Her second molars say she sailed from there, before she was eight, to somewhere else in the west. She did not arrive in Birka until she was over sixteen.

Where did she travel between her birthplace and her tomb? If all I had were her bones, I could only wonder. But I can also study what was buried with her. She was seated in her grave surrounded by weapons. None of them are overly fancy. None are simply for show. They are sturdy weapons, crafted for killing.

The two-edged sword beside her left hip is an uncommon type, rare in Norway and Sweden, but more often found along the Vikings’ East Way, the trade route through what is now Russia and Ukraine to Byzantium, Baghdad, and beyond.

Birka grave Bj581, as imagined by artist Þórhallur Þráinsson based on archaeologists’ interpretations.

Her long, thin-bladed sax-knife, or scramasax, in its elaborate bronze-and-silver ornamented sheath, is also Eastern, a rare and prestigious weapon—some say a status symbol—inspired by the equipment of the Magyar horse archers who haunted the steppes and harassed the Viking traders along the East Way.

Hervor was an archer, too, and may have shot from horseback. Hers is one of only eighteen graves at Birka—out of the eleven hundred excavated—to contain a horse, and hers are clearly riding horses. One of them was bridled with an iron bit; a second bit was found nearby. A pair of iron stirrups are all that remain of her wood-and-leather saddle. By her side were twenty-five spike-headed, armor-piercing arrows with elegant silver accents. Between the arrows and her scramasax was a bare spot, a gap, the right shape for a bow, which had disintegrated.

It may have been a Magyar bow. Though not preserved in her own grave, the distinctive metal rings and fittings of Magyar bow cases and quivers were recovered from other Birka graves of Hervor’s generation, as well as from the remains of the town’s fortress, which burned down a few years after she was buried and wasn’t rebuilt. Magyar bows, sometimes called horn bows, were composites of wood, sinew, and horn, bent into a reflex shape. Small and handy on horseback, they were equally suited to fighting on shipboard or defending a hillfort like the one that guarded Birka: They shot twice as far as an ordinary wooden bow. At close range they offered the skilled archer greater accuracy, speed, and penetration.

But Hervor was not solely a mounted archer. An archer’s weapon kit consisted of bow, arrows, spear, and shield. Hervor was buried with almost every Viking weapon known: sword, scramasax, arrows and bow, axe, two spears, and two shields. She was buried with more weapons than any other warrior in Birka; more than almost every Viking in the world. Of those Vikings found buried with any weapons at all, 61 percent have one weapon; only 15 percent have three or more.

Hervor’s grave is remarkable not only for its complete weapon set and sacrificed horses. Its location is equally impressive. From the main gate of the hillfort that crowned the island, an avenue led north or south. North, it passed between two groups of elite graves. South, it went to the Warriors’ Hall, where Birka’s garrison lived. Hervor’s grave lay west of the road, beside the hall. It was hard to miss: It was the only grave marked with a tall standing stone. It was also the grave set farthest west, perched to look down over the harbor and town, and out across the waters of Lake Malaren to the royal manor on the neighboring island of Adelso. From Hervor’s grave you could see everyone who came or went, to or from the busy town of Birka. Whoever Hervor was, the warriors of Birka honored her memory. They wanted her near to keep watch.

The prominent location of her grave, her panoply of weapons, the double sacrifice of valuable horses—these mark Hervor as a warrior of high status. A final touch elevates her rank to war leader: the full set of pieces for the board game hnefatafl, or Viking chess, that was placed in her lap. From the Roman Iron Age through the high medieval era, from Iceland to Africa to Japan, the combination of game pieces, weapons, and horses in a grave has indicated a war leader. Game pieces symbolize authority and a “flair for strategic thinking.” They express “the idea that success in warfare is not dependent on physical strength and dexterity alone but also on intelligence and the ability to foresee the actions of one’s opponents,” scholars say. In Viking terms, particularly, they attest to the warrior’s good luck.

Until the bones in Bj581 were determined to be female, no one doubted the warrior in the grave was a war leader. She was buried as a war leader—her gender seems not to have been worth mentioning. Individuality was not highly prized in the Viking Age. What mattered was not your unique and special self but your role in life. If you had the required qualities, physical and mental, you could fill any role; you became that role.

One role Hervor may not have filled is mother. Viking women are often found buried with two large oval or box-shaped metal brooches by their collarbones. These brooches, experts think, clasped the shoulder straps of a wool dress, cut like an apron or pinafore, worn over a low-necked linen shift. It was a practical design that made breastfeeding easy. Hervor did not wear an apron-dress; there are no brooches in her grave.

Based on what little does remain of her clothing, she dressed like the other Birka warriors. They affected an urban style, distinctive to the fortress towns along the East Way; it was a mixture of Viking, Slavic, steppe-nomadic, and Byzantine fashions. Under a classic Viking cloak, clasped with a ring-shaped iron pin at one shoulder, Hervor wore a nomad’s kaftan, a riding coat that wrapped in the front and was closed by a belt or buttons. It might have been made of Byzantine silk; in her grave was a scrap of fabric woven from silk and silver threads. It might have been decorated with mirrored sequins, a scattering of which were also found in her grave.

On her head she wore a close-fitting silk cap with earflaps that could be fastened up with silver buttons. It was topped by a filigreed silver cone that might have stuck up straight like a spike or flopped over like a tassel, depending on the cut of the cap. Only the buttons and cone and a scrap of silk remain of Hervor’s cap, but a silk cap perhaps like it was found in a fabric-rich grave in the Caucasus. An exact match for her cap’s filigreed silver cone was buried with another Birka warrior. A third matching cone was buried with a warrior near Kyiv.

Who was this valkyrie buried in grave Bj581? What might her life have been like? To tell Hervor’s story, I have to use my imagination. I have to make assumptions. I have to connect the dots.

Her bones say she lived to be thirty or forty. Archaeologists can rarely date their finds within a span of thirty years. Historians have a similar difficulty. The medieval sources are chronologically confused. Most were written down well after the events they record, and the accounts in different texts simply do not sync. Like anyone else studying the Viking Age, I’ll have to approximate. In Hervor’s case, the items in her grave suggest she died around the middle of the tenth century, when Birka was at its height and its connections to the East Way were strongest. The location of her grave implies she was buried after the Warriors’ Hall was built, around 930 or 950, but well before it burned down, between 965 and 985. To tell the best story, I’ll guess she was buried a little after 960 and born around 930.

Where exactly was she born? Science tells me only that she came from southern Sweden or Norway. Looking at the Viking world from a warrior woman’s point of view, I’ve opted for the kingdom of Vestfold, on the west side of the Oslo Fjord. Here, a hundred years before Hervor’s birth, two powerful women were buried in the most lavish Viking grave ever uncovered, the Oseberg ship mound. Here, when Hervor was a child, the great hall guarding the cosmopolitan trading port of Kaupang was destroyed—perhaps by Eirik Bloodaxe and Gunnhild Mother-of-Kings, who conquered Vestfold around that time.

Where would a small girl, born in the town of Kaupang to a rich family, if not royal, end up? Science suggests she went west, possibly to the British Isles—as did Eirik and Gunnhild sometime between 935 and 946, having lost Norway’s throne. From their base in the Orkney Islands, the royal pair meddled in the politics of the main Viking towns in the west, Dublin and York. Ruthless, ambitious, and fiercely intelligent, Gunnhild Mother-of-Kings makes a fine role model for a young valkyrie. Another role model is the Viking chieftain known as the Red Girl, active in the Irish Sea at that time.

When Eirik Bloodaxe was killed in England in 954, Gunnhild sought allies in Denmark. When the Danish king Harald Bluetooth helped put her sons on Norway’s throne in 961, Gunnhild ruled beside them for fourteen years: One medieval historian called it the “Age of Gunnhild.” Long before then, however, Hervor had quit Gunnhild’s court and become a Viking. She was already in Birka, defending the town, if she died there as war leader before the Warriors’ Hall burned down.

Yet, before her death, Hervor traveled on the East Way to Kyiv and back, if Kyiv is where she got the silver cone for her silk cap. If so, she met Queen Olga, who ruled the Vikings, or Rus, in Kyiv from about 945 until 957, when her son, Sviatoslav, came of age. In 971 Sviatoslav took the Rus south to challenge Byzantium, a raid that ended in disaster on a Bulgarian battlefield, where the Byzantine victors found warrior women among the Viking dead. Hervor was not among them; she had already been buried in Birka.

Besides this conjectural outline of Hervor’s life, what links Dublin and York to Kaupang, Birka, and Kyiv? The Viking slave trade, through which young men and women were exchanged for Byzantine silk and Arab silver. The Viking slave route passed the Danish island of Samsey, where perhaps Hervor stopped to plunder her father’s grave and retrieve his sword, as did her namesake in the poem Hervor’s Song. Let’s begin by imagining her there.

HERVOR’S SONG

Sunset on the isle of Samsey. A cold mist rolls in off the Kattegat. A shepherd gathering his flock for the night pauses on the dunes, alert, always alert on this small island famed as a meeting place of Vikings. And indeed, those sounds he hears, that rhythmic splashing, that groan and creak of oars, mean a ship is nearing—one or more. He throws himself flat in the long grass and listens.

He hears his sheep bleating as they trot homeward down the forest path, the bellwether leading. He wishes he were with them. He isn’t sure which is worse to meet here after dark: the Vikings in the approaching ships, or those buried under the mounds. Twenty years ago, two rival bands met here and fought: Angantyr and his eleven brothers against Arrow-Odd and his companions. All died except Arrow-Odd—people say he used magic. The dead haunt the shoreline still.

Beneath the raucous chatter of gulls, he listens to the breeze worrying the grass. An owl hoots, and the forest birds fall silent. The sun sinks lower; the mist thickens.

Now he hears voices, raised, and the rattle of weapons. A knocking of ships’ hulls, one bright and empty, the other weighty and dark. More oar splash. He is ready to run.

But what comes out of the mist is only a small boat rowed by a single warrior. The boat grounds and the warrior leaps out, drawing the vessel higher on the stony shingle. In spite of himself, the shepherd is curious. He lifts his head.

Immediately, the warrior spots him. You! she calls. Come down.

He rises to his feet, brushes off his bare knees, and slides down the dune to the beach. You’re crazy, coming here alone at nightfall, he says. Get to shelter before it’s too late.

The warrior gathers her gear from her boat. There’s no shelter for me here, she replies. I know no one living on this island.

When she turns toward him, he instinctively steps back. She is taller than he is, and much more muscular. Much wealthier, too. She wears a ringmail byrnie—he knows how heavy those are—but moves as if it were weightless. Beneath it she wears a good wool tunic, padded and embroidered, over wide wool pants, cross-gaitered below the knee. Silver glints at her throat. Her long hair is knotted at her nape.

Get back to your ship, he says. You can’t stay on the beach, not at night. It’s not safe to be alone here.

She claps a battered helm on her head, slips a hand axe into her belt. She picks up her shield and spear. You’re here with me, she says. Carry those. She points the spear tip at the rest of the pile: a broad axe, a shovel, a coil of rope.

The shepherd laughs. Only fools walk by the barrows at night. He gestures west, where the land is rippled by rows and clusters of grave mounds, some marked with tall upright stones, others shadowed by brush and trees. Two mounds stand higher than the rest, one by the shore, the other a little inland, on the edge of the salt marsh. Already he sees fires flickering in the mist as the sunset paints the sky red.

They’re scared too, she says, glancing over her shoulder at the invisible Viking ship. She turns back toward the mounds. Which is Angantyr’s?

We shouldn’t be standing here talking, he says. We should be heading home as fast as we can.

She unlinks a silver arm-ring and dangles it from a finger. I’ll give you this if you tell me where to dig.

The shepherd snatches it. He points to the nearer of the big mounds. Arrow-Odd buried his friends there in their boat, he says, and over there he buried his enemies, Angantyr and his brothers, in a wood-walled chamber. He claimed he did it alone, but of course we islanders helped him. We covered both graves with wood and turf and heaped sand over them. We left the dead with all their weapons, I swear it. But still they walk. At night, their graves open. This whole point of land bursts into flames.

It’s her turn to laugh, a scoffing laugh. I don’t faint at the crackling of a fire, she says.

Tossing her shield on the sand, she picks up the shovel and sets off for the barrow. She doesn’t look back, doesn’t see the shepherd disappear down the forest path.

Framed by the sunset, the barrow is on fire. Mist swirls around its base like smoke. She wades through it, unafraid. Circling the mound, she prods it with her spear. The turf and sand are not deep—you can’t expect much of a monument when your enemies bury you. Her spear tip touches wood and in one place pokes into it; the timbers are rotten. She won’t need the rope. She strips off her gear and starts digging at ground level. She takes her hand axe to the wood. Soon she breaks through.

When the tunnel is wide enough, she arms herself again and slips into the barrow—and only then realizes what she’s forgotten: light.

The grave is darker than night. She waits for her eyes to adjust, but not a glimmer from the sunset sky seeps in. Death surrounds her.

I will not tremble before you, Father, she says. Speak to me.

She closes her eyes but hears only silence and the wind in the world outside. One hand on the damp wooden wall of the tomb, she shifts forward until she can stand.

Awake, Angantyr! Angantyr, awake! she calls out. I am Hervor, Svava’s daughter, your only child. Give me your sword, the great sword Tyrfing, the Flaming Sword the dwarfs forged in their halls of stone.

Again, no answer. She takes another step forward and stumbles to one knee. She steadies her balance with her spear shaft, but one hand still comes down upon bones. She jerks her hand away.

May you writhe within your ribs, she curses. May your barrow be an anthill in which you rot. May you never feast with Odin in Valhalla, unless you let me wield that sword. Why should dead hands hold such a weapon?

And this time she thinks she hears an answer. You do wrong to call down evils upon me. No dead hands hold that sword. My enemies built this barrow. They took Tyrfing.

It could be true, though the shepherd swore not. She calls out again into the darkness: Would you cheat your only child? Tell the truth! Let Odin accept you only if the Flaming Sword is not here, in the tomb.

Silence. She opens her eyes and now flames do flash and flicker about her. She reaches for them, but they dance away.

Not for all your fires will I fear you, Father. It takes more than a dead man to frighten me.

You must be mad. Go back to your ships! No woman in the world would wield that cursed sword.

She knows of the curse: Once drawn, the sword must kill before it can be sheathed again. If not, it will doom her sons, destroy her family line—but what does she care about that? She has no sons, and no intention of marrying. She is a shield-maid. A warrior woman. A valkyrie.

People thought me man enough, she quips, before I came here.

Twelve bodies were buried in this barrow, her father and his eleven brothers. Angantyr, she reasons, was laid on top. Using her spear as a probe, she finds the edges of the pile, then its highest point. She pokes and prods until something falls to the floor that is not bone.

She shimmies out through the tunnel, her treasure tight in her fist: It is her father’s sword, gold-hilted Tyrfing, the Flaming Sword.

The mist has disappeared. The starlight seems so bright.

You’ve done well, Father, to give me your sword, Hervor says. I’d rather have it than rule all Norway.

Hervor’s Song was the first Old Norse poem to be translated into English, in 1703. As such, it crafted the image we hold today of the fearless Viking warrior who laughs in the face of danger—and that warrior is a woman.

My dramatization isn’t exact: The original includes no shovel. Instead, I’ve described what might have happened if Hervor’s Song reflected a real event—if, let’s say, this Hervor was the real warrior woman buried in grave Bj581 beside the Swedish town of Birka.

In the poem, the flames are real. The grave magically opens; the dead rise like smoke. Hervor conjures up her ghostly father and demands he hand over the family heirloom, the famous Flaming Sword. When he refuses, fearing the sword’s curse will destroy his family line, she scoffs and finally bends him to her will. “Now,” she brags, brandishing the sword, “I have walked between worlds.” The poem is eerie and otherworldly and has been popular, in English, for hundreds of years. Some say this poem inspired the first Gothic novel.

But the prose Saga of Hervor, which quotes the poem—and so preserved it for us to read—confounds modern readers. We like our genres clear-cut. Is it history? Is it fantasy? Is it true?

Medieval Iceland’s writers made no such distinctions. Those few sagas that do not mention dragons or ghosts, witches or werewolves, prophetic dreams or dire omens, dwell instead on the miracles of saints. The name “saga” implies neither fiction nor fact; it derives from the Old Norse verb segja, “to say.” A good saga seamlessly integrates the two. Some saga authors were witnesses to the events they relate; others retell stories from hundreds of years in their past. Some list their sources: folktales, poems, genealogies, or interviews with wise grandmothers. Others don’t. Some mimic foreign tales of chivalry; others focus on Icelandic farmers and their petty feuds.

All I can say for certain about the sagas is that they were first written down, in prose, after Christian missionaries created an Old Norse alphabet soon after the year 1000—no sagas are written in the ancient Norse runes—and that the copies we have were created in Iceland in the 1200s, 1300s, or even later.

A manuscript can be dated by what it’s written on (skin or paper), by the chemistry of its ink, by the shape of its letters and the abbreviations used, and by its vocabulary (though an ancient word hoard can be faked). Dating the stories and poems a manuscript contains is trickier. They are older than the parchment or ink, for sure. But how much older? For Hervor’s Song, I have a few clues.

The oldest copy of the Saga of Hervor was penned by an Icelandic lawyer named Haukur Erlendsson, as he tells us in letters from 1302 and 1310, though he only copied down the bits he liked. A longer (but much later) manuscript suggests the Saga of Hervor was first composed around 1120 for Queen Ingigerd of Sweden, whose mother was a princess from Kyiv. This version ends with a long list of kings descended (in spite of the sword’s curse) from Hervor, and the last on the list is Ingigerd’s husband.

The saga itself is set in a mythic Viking past that is impossible to date. Its story ranges from Norway east through Russia to the Black Sea and, as sagas go, it is not particularly well written. It could use “a ruthless rewriting” to smooth out its “many inconsistencies” and tie up its “loose ends,” according to its modern translator, and I have to agree. But it was apparently quite popular in the Middle Ages: Many manuscripts include a copy.

During the general “sorting frenzy” of the Victorian Age, the Saga of Hervor was classified as a Saga of Ancient Times, a genre created to dismiss a group of “mythical” or “romantic” tales “that have little or no historical authenticity,” as the translator put it. Yet, perversely, he prized the Saga of Hervor for its historical elements, which “come down from a very remote antiquity.” Those elements include Hervor’s Song and three other poems quoted in the text.

Saga scholars since the Middle Ages have deemed poems more authentic than prose. It was common for Viking kings and queens to retain court poets to record their deeds. “People still know their poems,” wrote the Icelandic author Snorri Sturluson in the 1200s. Like sonnets or haiku, Viking Age poetry had elaborate rules for rhyme, rhythm, and alliteration. These rules made poems harder to tinker with—and easier to memorize—than prose. “If a verse is composed correctly,” Snorri asserted, “the words in it will remain the same, even as they are passed down from person to person” for hundreds of years.

Modern readers tend to agree with him: Most of what we think we know about the Viking mind comes from Viking poetry. Much of Viking history derives from poetry as well. For his Heimskringla (or Orb of the World), a collection of sixteen sagas about Norway’s kings, Snorri expanded upon “what is said in the poems recited before the rulers themselves or their sons.” Of course, he admitted, poets exaggerate: “It is the way of poets to praise most those to whom they are speaking,” he said (and Snorri was himself a poet). But no one would dare to recite a poem praising the rulers for things that they—and everyone listening—knew were false. “That would be mockery, not praise.” For that reason, Snorri took to be true “all that can be found in those poems about their travels or their wars.”

If I apply Snorri’s rule to the Saga of Hervor, it’s hard not to conclude that some Viking women were warriors.

The first poem in the saga tells how the Viking warrior Angantyr came to be buried on the Danish isle of Samsey before his only child was born. Hervor, says the prose between the poems, grew up with her grandfather, a chieftain, thinking she was the swineherd’s bastard. A difficult child, she preferred archery and swordplay to sewing and embroidery. As a teen she ran off and lived wild in the woods, robbing and killing passersby before being hauled back to court, where she annoyed everyone with her rudeness. When she finally learned her father was a famous Viking warrior, not a swineherd, she resolved to be like him. She ordered a new shirt and cloak, demanding her mother give her “everything you would give to a son.” She renamed herself Hervard, the masculine form of her name—and the saga author follows suit, referring to her as “he,” not “she.”

Hervard joined a Viking band and quickly rose to lead it. Raiding in the Kattegat, among the Danish islands, he led his band to Samsey and proposed they break into the grave mounds to reclaim his family treasure. His crew feared waking the dead, so he rowed to the island alone. Here the saga writer inserted Hervor’s Song, in which Hervard reveals himself to be Angantyr’s daughter and declares she would rather have her father’s sword “than rule all Norway.”

In the saga, this Hervard-Hervor eventually gives up the Viking life, marries, and has two sons. The third poem quoted in the saga is a set of riddles associated with one of them, King Heidrek the Wise. One riddle, aptly, refers to warrior women:

Around a weaponless

king, what women

are fighting?

The fair attack him,

the red defend him,

day after day.

The answer to the riddle is the board game hnefatafl, or Viking chess. Hervor, the saga says, was an expert player, better than the king under whose banner she fought.

Her skill explains how she could become a Viking leader: Not only had she trained with weapons since childhood, she displayed that flair for strategic thinking so prized in the Viking Age. Success depended on surprise—a Viking band was often outnumbered. But surprise depended on skill. A good leader took care of logistics: Her band was well fed and rested, and their ship and equipment in good shape before a raid. She could read the weather and water; she didn’t get lost. Her contacts (and spies) kept her well informed of which kings were at war (and so looking elsewhere). She knew her enemies’ tactics, and how to trick them. She knew when fairs were held and harvests brought in, the routes of the tax collectors and traders. She could rouse her fighters to battle frenzy, make them laugh at defeat, and engineer their escape. She had good luck—in a pinch, she could be counted on to make the right choice—and she never gave up. She dressed as a man for practical reasons, not to fool anyone—there’s no privacy on a Viking ship, not even a deck to go below. She announced her sex the first time she pissed. She took a man’s name to announce her role: She was a warrior.

The final poem in the Saga of Hervor features a second shield-maid named Hervor. In the saga she is the first Hervor’s granddaughter, but scholars think the chronology’s mixed up. This poem, they believe, tells of an ancient war some four hundred years before the Viking Age began. If so, The Battle of the Goths and the Huns may be “the oldest of all the heroic lays preserved in the North.”

The poem is set beside the forest of Mirkwood, on the border between the Goths, who were ruled by one of this Hervor’s two brothers, and the Huns, from whom her second brother had raised an army to challenge his sibling’s rule. Hervor commanded the border fortress. One morning, from the tower above her fortress gate, she watched as a great cloud of dust rolled out from the shadows under the trees. It glittered as it moved. She called her trumpeter. “Summon the host,” she said, and when her warriors gathered: “Take up your weapons and prepare for battle.” By the time the Huns arrived on their fast horses, glittering in ringmail and helmets and wielding their deadly horn bows, Hervor was ready. She rode out at the head of her army, and the battle began. But she was badly outnumbered. She and her captains were killed, all but one; he rode night and day to bring the news to the king of the Goths. The king took no time to mourn his sister—she had been happier in battle than other women were when chatting with their suitors, the poem says—but set forth at once to avenge her. He met the Huns on the plains of the Danube. The battle raged for days, until the Goths, their ranks constantly reinforced as the news spread, repelled the Hun invaders, leaving so many dead that the rivers were dammed with corpses and overflowed their banks.

If The Battle of the Goths and the Huns is truly the oldest epic song of the north, then the idea of the warrior woman was embedded in Viking culture from its very start.

A Viking rider and a standing warrior, less than an inch tall, from Tisso, Denmark. Near- identical amulets have been found in England and Poland.

The Christian writer of the Saga of Hervor, stitching four ancient poems into a tale in twelfth-century Sweden, struggled with that idea and ultimately rejected it. Though the Gothic Hervor who guards the border remains a hero (if a failed one), her grave-robbing namesake in Hervor’s Song is thoroughly undermined. She is cruel, willful, self-centered, greedy, light-minded, and not, in the end, a good leader. Her role in the saga, it seems, is to warn against letting your daughters run wild.

In the poem, the shepherd on Samsey is not surprised to see a warrior woman, only to see anyone foolhardy enough to face the ghost-fires. Neither is Hervor’s ghostly father, Angantyr, surprised to see her in armor or commanding a fleet of Viking ships. He finds her “not like other people” (another translation is “hardly human”) not because she wants to wield a sword, but because she wants this sword: the cursed sword that will destroy all their kin. Even the saga writer, introducing the poem, matter-of-factly identifies Hervor as the leader of a Viking band. Yet after winning her father’s sword, the saga says, Hervor returned to the shore to find her companions had deserted her.

It’s unlikely. A Viking band was a team, its success dependent on cooperation and trust. Its members were closer than kin.

Though fighters from the same families often joined the same bands, Viking bands were notable for their diversity. Bands included men and women, young and old, rich and poor, warriors from the same region and those from far off, even those who spoke different languages and worshipped different gods, all brought together by a leader’s reputation for good luck.

Viking bands were notable, too, for their loyalty: They swore a binding oath. Elaborate rites and symbols also bound them: They painted their ships or shields with certain colors or patterns, affected a certain style of dress, followed a single banner. They wore or carried amulets or badges fashioned as miniature ships, spearheads, hammers, swords, falcons, dragons, wolves, and people, both men and women, tearing out their hair or bearing weapons, standing or riding or both. These may have been lucky charms or religious totems, or they may have functioned like the challenge coins modern soldiers must produce on demand to prove they belong to a certain unit.

Most of all, the members of a Viking band were bound by common experiences: the spiritual release of rituals, the trauma of the battlefield, the dangers of sea travel, and the overindulgence that defined a good feast, where boasting and storytelling both created and expressed their shared identity, and oaths were sealed with a drink.

If the Christian author of the Saga of Hervor had believed in the reality of Viking warrior women, if that writer had known what it meant to be a Viking leader—or had understood Hervor’s meaning when she quipped she was thought “man enough”—her story might have continued like this:

When Hervor returned from the grave mounds, she found her ship moored in a creek on the lee side of the cape. Her crew had butchered a stolen sheep and were stewing bits of it in an iron pot over their campfire—all but the warriors left guarding the ship. Hervor joined their circle and set to cleaning Tyrfing, the Flaming Sword, scraping away the moldering remains of the wood-and-leather sheath, oiling away the rust and tarnish, and honing the edge with her whetstone. Finished, she raised a horn of beer and recounted—in verse—how she had taken the sword from her ghostly father.

The sword buried with the warrior woman in Birka grave Bj581, the Hervor of this book, was not the gold-hilted Tyrfing. It was a simple, sturdy weapon, of a style most often found in Sweden, Russia, and Ukraine.

I can only guess how she earned it.

Perhaps, like her poetic namesake, she took it from a grave. The Persian historian Miskawayh, who chronicled a Viking raid on a town in Azerbaijan in 943, noted that the slain Vikings were buried with their swords. But these swords were in high demand “for their sharpness and excellence,” so as soon as the rest of the Vikings left town, their enemies reopened the graves, picked out the swords, and sold them.

In the Icelandic sagas, grave robbing is not so simple—or safe. Some attempts involve terrifying confrontations with reanimated corpses, zombies who can only be overcome if their heads are cut off and set between their buttocks. The poetic Hervor’s argument with her ghostly father is tame by comparison. Yet archaeologists have found breaking into Viking barrows to be common—nearly every large grave mound from the Viking Age shows signs of intruders. It may have been the usual practice to retrieve heirlooms like swords.

Not all Viking swords were buried, even temporarily. Many were passed down from generation to generation. Such was the case with Tyrfing before Hervor’s father, Angantyr, took it to the grave. According to the Saga of Hervor, Tyrfing was made by two dwarfs (under duress) for a Viking chieftain in Russia. He gave it to the Swedish Viking who married his daughter. They took Tyrfing to Sweden, and some twenty years later the Viking gave it to his eldest son, Angantyr, before he and his brothers set off to challenge their enemies on the Danish isle of Samsey. “I think you will have need of good weapons,” their father said. The poetic Hervor was the fourth generation to wield the Flaming Sword; her last act in the saga is to give it to her son.

The hero of Grettir’s Saga had a sword with a similar lineage. He received Jokul’s Gift from his mother, secretly, because his father did not think he deserved a weapon. As Grettir set out from home, his mother “took a sword out from under her cloak; it was her most valuable possession. She said, ‘My grandfather Jokul owned this sword, and other Vatnsdalers before him, and it brought them victory.’” She added, “I think you will have need of it.”

Swords were won in battles and duels; they were also traded among friends. In Egil’s Saga, Egil gave his friend Arinbjorn two gold arm-rings. In return, Arinbjorn gave Egil a sword named Slicer. Arinbjorn had received Slicer from Egil’s brother, who in turn had received it from Egil’s father; he had it from his brother, who got it from a friend, who got it from his own father—altogether, Slicer had seven owners over three generations.

The sword’s biography added to its value: It tied its owners together in a web of friendship. “Long friendships follow frequent gifts,” says the Viking creed, Havamal, or