9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Restoration

- Sprache: Englisch

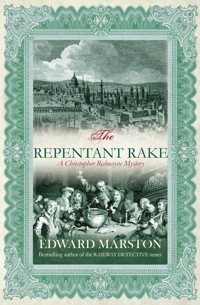

When Sir Julius Cheever's son, a notorious rake, goes missing, and a blackmailer begins terrorising London's most dissolute fops, it seems plausible that the two events are connected. Divided by politics but united in a desire to see justice done, Christopher Redmayne and Jonathan Bale must combine forces once again. But how can they hope to find those who exploit the scandal of others, when the victims themselves will do anything to maintain their anonymity? And what of Sir Julius's son? Most feel he must have been the victim of his own, debauched appetites, but a few talk of his repentance. So where is the repentant rake? And, with only lies, rumours and gossip to work with, can Redmayne and Bale ever hope to find him?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 482

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

The Repentant Rake

EDWARD MARSTON

In memory of Arthur Heale, friend and historian, who first took me down the long road into the past.

‘The pleasure past, a threat’ning doubt remains,That frights th’enjoyer with succeeding pains.’

A SATYR AGAINST MANKIND: LORD ROCHESTER

Contents

Title PageDedicationEpigraphCHAPTER ONECHAPTER TWOCHAPTER THREECHAPTER FOURCHAPTER FIVECHAPTER SIXCHAPTER SEVENCHAPTER EIGHTCHAPTER NINECHAPTER TENCHAPTER ELEVENCHAPTER TWELVECHAPTER THIRTEENCHAPTER FOURTEENThe Restoration seriesThe Railway Detective seriesThe Captain Rawson seriesAbout the AuthorBy Edward MarstonCopyright

CHAPTER ONE

‘London is a veritable cesspool!’ he said, banging the table with a bunched fist. ‘A swamp of corruption and crime.’

Christopher shrugged. ‘It has its redeeming features, Sir Julius.’

‘Does it?’

‘I think so.’

‘Well, I’ve never seen any of them. A capital city should be the jewel of the nation, not a running sewer. The place disgusts me, Mr Redmayne. It’s full of arrogant fools and strutting fops. Babylon was a symbol of decency compared to it. Immorality runs riot in London. Whores and rogues people its streets. Drunkards and gamesters haunt it by night. Foul disease eats into its vitals. And the worst villains of all are those who sit in Parliament and allow this depravity to spread unchecked.’

The tirade continued. Christopher Redmayne listened patiently while his host unburdened himself of his trenchant views. Sir Julius Cheever was not a man to be interrupted. He charged into a conversation like a bull at a gate and it was wise to offer him no further obstruction. Sir Julius was a wealthy farmer, big, brawny, opinionated and forthright. Now almost sixty, he bore the scars of war with honour on his rubicund face but it was his wounded soul that was now on display. The oak table was pounded once again. Eyes flashed.

‘Why, in the bowels of Christ, did we let this happen?’ he demanded. ‘Did we spill all that blood to end up with something even worse than we had before? Has there been no progress at all? London is nothing but a monument to sin.’

‘Then I am bound to wonder why you wish to build a house there, Sir Julius,’ said Christopher gently. ‘Given your low opinion of the capital, I would have thought you’d shun rather than seek to inhabit the place.’

‘Necessity, Mr Redmayne. Necessity drives me there.’

‘Against your will, by the sound of it.’

‘My conscience has subdued my will.’

Christopher found it difficult to believe that anything could subdue Sir Julius Cheever’s will. He positively exuded determination. Once set on a course of action, he would not be deflected from it. Evidently, his obstinacy and blunt manner would not make him an easy client but Christopher was prepared to make allowances. The commission appealed to him. In the interests of securing it, he was prepared to tolerate the old man’s rasping tongue and uncompromising views.

‘Let me explain,’ said Sir Julius, legs apart and hands on his hips. ‘I’m an unrepentant Parliamentarian and I don’t care who knows it. I fought at Naseby, Bristol, Preston, Dunbar and Worcester with the rank of colonel. You can see the results,’ he added, indicating the livid scar on his cheek, the healed gash above one eye and the missing ear. ‘The Lord Protector saw fit to reward me with a knighthood and I was grateful. Not that I agreed with everything he did, mark you, because I did not and he was left in no doubt about that. I favoured deposition of the king, not his execution. That was a cruel mistake. We are still paying for it.’

‘You spoke of conscience, Sir Julius.’

‘That is what is taking me to London.’

‘For what reason?’

‘To begin the process of cleansing it, of course. To root out vice before it takes too firm a hold. I’m not a man to stand back when there’s important work to do, Mr Redmayne. I have a sense of duty.’

‘I can see that.’

‘Parliament needs people like me. Honest, upstanding, God-fearing men who will lead the fight against the creeping evil that has invaded our capital. I will shortly be elected as one of the members for the county of Northampton and look to knock a few heads together when I get to Westminster.’

Christopher smiled. ‘I wish that I could see you in action, Sir Julius.’

‘Fighting is in my blood. I’ll not mince my words.’

‘You’ll cause quite a stir in the seat of government.’

‘The seat of government deserves to be kicked hard and often.’ Sir Julius gave a harsh laugh then stopped abruptly to pluck at his moustache.

They were in the parlour of the Cheever farmhouse in Northamptonshire. It was a big, sprawling, timber-framed structure, built with Tudor solidity but little architectural inspiration. The room was large, the oak floor gleaming and the bulky items of furniture suggesting money rather than taste. Christopher suspected that the place had looked identical for at least half a century. Sir Julius Cheever belonged there. He had the same generous dimensions, the same ignorance of fashion and the same hopelessly dated air. Yet there was something strangely engaging about him. Beneath the surface bluster, Christopher detected an essentially good man, given to introspection and animated by motives of altruism. He could see that Sir Julius would be a loyal friend but an extremely dangerous enemy.

Christopher was seated in a high-backed chair but his host remained on his feet. Stroking his moustache, Sir Julius studied his guest carefully before speaking.

‘Thank you for coming so promptly, Mr Redmayne,’ he said.

‘Your letter implied urgency.’

‘I make decisions quickly.’

‘And are you firmly resolved to have a town house in London?’

‘Now that I am to sit in Parliament, it is unavoidable.’

‘There may be some delay, Sir Julius,’ warned Christopher. ‘Houses are not built overnight. When you first come to London, you will have to find other accommodation.’

Sir Julius waved a hand. ‘That’s all taken care of,’ he said dismissively. ‘My daughter, Brilliana, lives in Richmond with her dolt of a husband. I’ll lodge with them until my own abode is complete. The sooner it’s ready, the better.’

‘I, too, can work quickly when required.’

‘That’s what I was told.’

‘Does that mean you are engaging me to design your new house?’

‘No, Mr Redmayne,’ said the other. ‘It means that I brought you here to gauge your fitness for the task. You are the third in line. It’s only fair to tell you that your two predecessors were found seriously wanting.’

‘You didn’t care for their draughtsmanship?’

‘It was their politics that I couldn’t stomach.’

‘I hope that I don’t fall at the same hurdle, Sir Julius.’ Christopher was puzzled. ‘Before you put me to the test,’ he said, ‘may I please ask a question?’

‘Of course.’

‘How did you first become aware of my work?’

‘Through the agency of a friend – Elijah Pembridge.’

Christopher was surprised. ‘The bookseller?’

‘I can read, you know,’ said Sir Julius with a twinkle in his eye.

‘Yes, yes, naturally. What surprises me is that someone so decidedly urban and bookish as Elijah Pembridge should number a country gentleman among his acquaintances.’

‘I’m rather more than that, sir.’

‘So I see.’

‘Elijah tells me that you designed his new premises in Paternoster Row.’

‘That’s right, Sir Julius. The original shop was burnt to the ground in the Great Fire. It was a pleasing commission. He was a most obliging client.’

‘And you, I understand, were an equally obliging architect. He found you polite and efficient, able to give sound advice yet willing to obey his wishes. Thanks to you, the place was built a month ahead of schedule.’

‘Only because I chose a reliable builder.’

‘Such men, I gather, are few in number.’

Christopher was circumspect. ‘That’s an exaggeration, Sir Julius. There are plenty of excellent builders in London but they are, for the most part, already engaged on the major projects that were necessitated by the Great Fire. Others, less scrupulous, have flocked to the capital. Speculators are the real problem,’ he went on, a slight edge in his voice. ‘Ruthless men who put commercial gain before architectural considerations. They throw up whole streets of houses in no time at all, augmenting their number by giving them narrow frontages and small gardens. Simplicity is their watchword, Sir Julius. They erect identical brick boxes for their clients. Whereas a true craftsman will build an individual dwelling.’

‘That’s what I require, Mr Redmayne.’

‘Then I’ll be happy to discuss the matter with you.’

‘The plot of land is already secured.’

Christopher nodded. ‘So you said in your letter, Sir Julius. I took the liberty of visiting the site. It’s well chosen. You invested wisely.’

‘Not for the first time, my young friend.’

‘Oh?’

‘I have an instinct that rarely lets me down.’

‘You’ve bought property elsewhere?’

‘From time to time, but I was not thinking of the purchase of land.’ He took a step closer. ‘The name of Colonel Pride is not, I dare say, unknown to you.’

‘Everyone has heard of Pride’s Purge,’ replied Christopher. ‘His hostility to the House of Commons was given full vent when he expelled all those members from their seats. I fancy that he gained much satisfaction from that day’s work.’

‘Tom Pride and I fought together,’ said Sir Julius, ‘but our friendship did not end there. We went into business together. Colonel Pride was head of a syndicate that secured a contract to victual the Navy. I was one of his partners.’ He gave a complacent smile. ‘As I told you, farming is only one string to my bow.’

Christopher was grateful for the information. He had known that he had heard of Sir Julius Cheever before but could not recall when and in what context. His memory was now jogged. Sir Julius had been mentioned in connection with the Navy.

‘My brother, Henry, dealt with your syndicate, I believe,’ he said.

Sir Julius shook his head. ‘Henry Redmayne? Don’t know the fellow.’

‘He holds a position at the Navy Office.’

‘Does he?’

‘Henry handled the victualling contracts at one point.’

‘They were very profitable, in spite of a few ups and downs. So,’ said Sir Julius, appraising him afresh. ‘You have a brother, do you? Any other siblings?’

‘None, I fear.’

‘And no family of your own, I’d guess. You have the look of a single man.’

Christopher grinned. ‘Is it that obvious, Sir Julius?’

‘There’s an air of independence about you.’

‘Some might call it neglect.’

‘Why have you never married? Lack of opportunity?’

‘Money is the critical factor,’ admitted Christopher. ‘I’m still making my way in my profession and have yet to establish a firm enough foundation to my finances. A husband should be able to offer a wife security.’

‘Quite so,’ agreed the other. ‘Romantic impulse is all very well but a full purse is the best guarantee of a happy marriage. That’s the one asset my son-in-law does actually possess. Lancelot has little else in his favour.’ He gave a nod of approbation. ‘You’re a practical man, Mr Redmayne. I admire that in you. And after Elijah’s recommendation, I have no qualms about your ability as an architect. That brings us to the crucial question.’

‘Does it, Sir Julius?’

‘Yes, my young friend. What are your politics?’

Christopher gave another shrug. ‘I have none.’

‘None at all?’

‘Not when I’m working for a client.’

‘You have no views, no opinions on the state of the nation?’

‘Only on the state of its architecture, Sir Julius.’

‘Every sane man takes a stand on politics.’

‘Then I’m the exception to the rule,’ said Christopher with a disarming smile, ‘for I find politics a divisive issue. Why look for a reason to fall out, Sir Julius? If we can come to composition over the design of a new house, that is all that matters. My politics are immaterial. You’d be employing me as an architect, not appointing me as the next Lord Chancellor.’

Sir Julius was so taken aback by the rejoinder that he goggled for a full minute. Surprise then gave way to amusement and he emitted a peal of laughter that filled the room. It was at that precise moment that his daughter entered. Susan Cheever was clearly unaccustomed to seeing her father shake with mirth. She blinked in astonishment at him. Christopher rose swiftly from his seat, partly out of politeness but mainly to get a clearer view of the beautiful young woman who had just sailed in through the door. Susan Cheever was a revelation. A slim, shapely creature of medium height, she had none of her father’s salient features. For all his eminence, he was patently a son of the soil, but she seemed to have come from a more ethereal domain. It was the luminous quality of her skin that caught Christopher’s eye. It glowed in the bright sunlight that was flooding in through the windows. When she spoke, her voice was soft and melodious.

‘I wondered if your guest would be dining with us, Father?’ she asked.

‘Oh, yes,’ he replied firmly. ‘Mr Redmayne will not only be gracing our table at dinner, he’ll be here for the rest of the day. Mr Redmayne will need a bed for the night as well,’ he decided. ‘I think I’ve found the right man at last, Susan. He’s just made the most politic remark about politics.’

Sir Julius laughed again but Christopher ignored him. His gaze was fixed on Susan Cheever. Attired in a dress of blue satin whose close-fitting bodice advertised her figure, she looked delightfully incongruous in a rambling farmhouse. Their eyes locked for the briefest moment but it was enough to give him a fleeting surge of excitement. Offering him a token smile, she left the room. Her father’s comment carried with it the seal of approval. If he were being invited to stay the night, Christopher must have secured the lucrative commission. He was thrilled. He would not only be designing a house for an interesting client, he would have the pleasure of getting to know Sir Julius Cheever’s younger daughter. The long ride to Northamptonshire had been more than worthwhile.

He could still smell the fire. It was almost two years since the fateful night when he had been hauled from his bed to fight the conflagration but Jonathan Bale still had that whiff of smoke in his nostrils. As he walked along the dark street, he could even feel the heat striking up at his feet again from the scorched ground. His clothing became an oven. Sweat began to trickle. Invisible smoke clouded his eyes. He was untroubled. Jonathan was used to being tormented by such memories. When he heard the crackling of the flames and the screams of hysteria, he shook his head to dismiss the familiar sounds. The Great Fire would burn on in his mind for ever. He had learnt to live with it.

‘Will it ever be the same again?’ he asked.

‘What?’ grunted his companion.

‘Our ward.’

‘No, Jonathan. We’ve seen the last of the real Castle Baynard.’

‘Much has been rebuilt, Tom.’

‘Yes, but not in the same way. We lost homes, inns, churches, warehouses and the castle itself. How can we ever replace all that?’

‘They’re doing their best.’

‘I preferred it the way it was.’

Tom Warburton was a tall, stringy, humourless man. Jonathan was dour by nature but he appeared almost skittish by comparison with his fellow constable. A middle-aged bachelor with no interests outside his work, Warburton took his duties seriously and discharged them with grim commitment. He was an effective officer of the law but he lacked sensitivity and compassion. Jonathan Bale, by contrast, cared for the inhabitants of his ward and took the trouble to befriend many of them. While he was firm yet fair with offenders, Warburton was merciless. Given the choice, the petty criminals of the area would always prefer to be arrested by Jonathan. The bruises did not last quite so long.

It was late. Their patrol took them through the darkest parts of the district. Candles burnt in an occasional window and a passing link boy brought a sudden blaze of light but they were, for the most part, making their way along familiar streets by instinct. Warburton was not a talkative man. He liked to keep his ears pricked for the sound of danger. It was Jonathan who always initiated conversation.

‘A quiet night,’ he noted.

‘Too quiet.’

‘Most people are abed.’

‘But not all of them with their lawful wives and husbands,’ said Warburton sourly. ‘The leaping houses will be as full as ever.’

‘We can’t close them all down, Tom. As soon as we raid one place, another opens up elsewhere. And no matter how big the fine, they always have money to pay it. Vice, alas, is a rewarding trade.’

‘I’d like to reward every whore with a long term behind bars.’

‘It’s not only the women who are to blame,’ said Jonathan. ‘Many are driven to sell their bodies by poverty or desperation. I could never condone what they do but I am bound to feel sorry for them. It’s their clients who are the real culprits. Midnight lechers, buying their pleasures at will. If there were no demand, the brothels would not exist. And if there were no brothels,’ he added darkly, ‘there’d be a lot less drunkenness and affray. In the company of such women, men are always given to excess.’

Warburton said nothing. His ears had picked up the noise of a distant altercation. Voices were raised in anger, then a fight seemed to develop. The two men quickened their pace. By the time they reached Great Carter Lane, however, the argument had resolved itself. One of the disputants had been knocked to the ground outside an inn and the other had rolled off cursing into the night. Before the constables could reach him, the downed man dragged himself to his feet and scuttled away down an alley. Violence was a regular event inside the Blue Dolphin. This particular row had spilt out into the street to be settled with bare fists. All that Jonathan and Warburton could do was exchange a sigh of resignation and continue on their way. There would be plenty of other brawls in their ward before the night was done.

They were walking down Bennet’s Hill when Jonathan felt something brush against his leg. It was Warburton’s dog, a busy little terrier that always accompanied its master on his rounds. Sam was an unusual animal. He never barked. During a patrol such as this, he would disappear for long periods then materialise out of thin air when least expected. Warburton treated the dog with a mute affection. It was both his scout and his bodyguard. If his master were attacked, Sam would come to his aid at once. More than one vicious criminal had been put to flight by those sharp teeth. Having returned for a moment, the dog scampered off down the hill and merged with the shadows. Jonathan knew where he was going. Their walk would take them down to Paul’s Wharf and there were always vermin to catch beside the river. Sam would be in his element. When they saw him next, he would be holding a dead rat in his jaws.

Rebuilding had begun in earnest. Since the Great Fire, twelve hundred houses had already sprung up along with inns, warehouses and other buildings. Churches had yet to be replaced. Almost ninety had been destroyed by the blaze, including the church of St Benet Paul’s Wharf. As they went past its charred remains, Jonathan recalled how he had fought in vain alongside others to save it from the flames. The loss of its churches was a bitter blow to the ward. While religion slept, Jonathan believed, sinfulness came in to take its place. He was still musing on the impact of the fire when they finally reached the wharf. Sam was waiting for them. They could pick him out in the moonlight. As they got closer, they saw that he held something between his teeth.

Jonathan assumed it would be another victim from the rat population but he was wrong. When the dog trotted across to his master and laid his trophy at Warburton’s feet, it was no dead animal this time. What the constable picked up was a man’s shoe with a silver buckle on it. It was too dark to examine the item properly but he could tell from the feel of it that it was the work of an expensive shoemaker. He handed it to Jonathan who came to the same conclusion. Tongue out and panting quietly, Sam knew exactly what to do. He swung round and loped away, leading them to the place where he had found the discarded shoe. Jonathan and Warburton followed him down to a warehouse not far from the water’s edge. The Thames was lapping noisily at the wharf, giving off its distinctive odour. A faint breeze was blowing. Sam went along the side of the warehouse, then stopped to sniff at something in a dark corner. Jonathan was the first to reach him. The dog had led them to the other shoe, but it was different from the first. It was still worn by its owner, who lay hunched up on the ground. Jonathan bent down to carry out a cursory inspection of the man, but he had already sensed what he would find. His voice took on urgency.

‘Fetch some light, Tom,’ he ordered. ‘I think he’s dead.’

CHAPTER TWO

Christopher Redmayne was delighted that he was leaving with a new commission under his belt but sorry that he had not had the opportunity to become more closely acquainted with his client’s younger daughter. Susan Cheever had made a deep impression upon him, and though he told himself that someone that attractive must have a whole bevy of male admirers in pursuit of her, perhaps even a potential husband in view, it did not prevent him from thinking about her obsessively when he was alone. The problem was that he was very rarely on his own to luxuriate in his thoughts. Sir Julius Cheever was a possessive man who hardly let his guest out of his sight. Susan had joined them for dinner on the previous day but said little and left well before the meal was finished. Her appetite simply could not accommodate the fricassee of rabbits and chicken, the leg of mutton, the three carps in a dish, the roasted pigeons, the lamprey pie and the dish of anchovies that were served. Long before the sweetmeats arrived, she had made a polite excuse and withdrawn from the table.

Dinner had continued well into the afternoon. Sir Julius ate heartily and drank deeply from the successive bottles of wine. Christopher simply could not keep pace with him. Besides, he wished to keep his head clear for their business discussion and that ruled out too much alcohol. The huge meal eventually told on his host and he fell asleep in the middle of a long diatribe for all of ten minutes, waking up with a start to complete the very sentence he had abandoned and clearly unaware that there had been any hiatus. Sir Julius knew exactly what he wanted in the way of a town house. His specifications were admirably clear and Christopher was duly grateful. Previous clients had not always been so decisive. Sir Julius brought a military precision to it all, tackling the project with the controlled eagerness of a commander issuing orders to his army on the eve of battle. When the long oak table in the dining room had been cleared, he stood over the young architect while the latter made some preliminary sketches.

It had been a long but productive day. Susan joined them again for a light supper and Christopher gained more insight into her relationship with her father. She chided him softly for keeping his guest up too late yet showed real concern when he complained about pain from an old war wound in his leg. As the night had worn on, Sir Julius came to look more tired, more lonely and, for the first time, more vulnerable. He turned to maudlin reminiscences of his deceased wife. Susan interrupted him, soothing and censuring him at the same time, bathing him in sympathy while insisting that it was unwise for him to stay up so late. It was almost as if she had taken on the role of her mother. Christopher was touched by the unquestioning affection she displayed towards Sir Julius and impressed by the way she handled him. His only regret was that the closeness between father and daughter obviated any chance of time alone with Susan. Retiring to his bed, an ancient four-poster with a lumpy mattress, he slept fitfully.

After breakfast next morning, on the point of departure, he finally had a brief conversation alone with her. Sir Julius went off to berate a tardy servant and the two of them were left at the table. Christopher had rehearsed a dozen things to say to her in private but it was Susan Cheever who spoke first.

‘I must apologise for my father, Mr Redmayne,’ she said with a wan smile. ‘His manner is a trifle abrupt at times.’

‘Not at all, Miss Cheever.’

‘When you get to know him, you’ll see that he has a gentler side to him as well.’

‘I see it embodied in you,’ said Christopher with an admiring smile. ‘Apologies are unnecessary. I find Sir Julius a most amenable client. It will be a pleasure to work for him.’ He fished gently for information. ‘Your father mentioned a second daughter with a house in Richmond.’

‘Yes, Mr Redmayne,’ she said. ‘My sister, Brilliana.’

‘I understand that he’ll be staying there in due course.’

‘Until the new house is built.’

‘That will be done with all haste.’

‘I’m glad to hear it.’

‘Will you be travelling to London with your father, Miss Cheever?’ he asked, raising a hopeful eyebrow.

‘Occasionally,’ she replied. ‘Why do you ask?’

‘Because Sir Julius is a different man with you beside him.’

‘In what way?’

Christopher was tactful. ‘He seems to mellow.’

‘It’s largely exhaustion.’

‘I marvel at the way you look after him so well.’

‘Someone has to, Mr Redmayne,’ she sighed. ‘Since my mother died, he’s been very restless. It’s one of the reasons he wishes to take up a political career. It will keep him occupied. Father pretends to hate London yet he wants be at the centre of events.’

‘What about you, Miss Cheever?’ he said, keen to learn more about her.

‘Me, sir?’

‘Do you relish the idea of being at the centre of events?’

‘Oh, no,’ she said solemnly. ‘I have no love for big cities. To be honest, they rather frighten me. I was born and brought up in this beautiful countryside. Why surrender that for the noise and filth of London?’

‘London has its own attractions.’

‘I know. My sister Brilliana never ceases to talk about them in her letters. She and her husband frequently take the coach into the city. Brilliana seems to keep at least three dressmakers in business.’

‘Is her husband engaged in politics?’

‘Lancelot?’ She gave a little laugh. ‘Heavens, no! Lancelot is no politician. He’s far too nice a man to entertain the notion of entering Parliament. My brother-in-law is a gentleman of leisure. Running his estate and pampering Brilliana take up all his time.’

‘Talking of estates,’ said Christopher, glancing towards the window, ‘you must have a sizeable one here in Northamptonshire.’

‘Almost a thousand acres.’

‘Sir Julius is obviously a highly successful farmer.’

‘He inherited the land from my grandfather and extended it over the years.’

‘It’s a pity that he has nobody else to carry on the good work. Farming runs in families. Sons take over from fathers. But since you have no brother the Cheever name may have to make way for someone else.’ Susan turned away in mild embarrassment. Christopher was immediately contrite. ‘Have I said something to offend you?’ he asked. ‘I do apologise. It was not intentional, I promise you. In any case, Miss Cheever, it’s none of my business. Please forgive me. I’d not upset you for the world.’

She met his gaze. ‘There’s nothing to forgive.’

‘I made a crass remark and I’m truly sorry.’

‘How were you to know, Mr Redmayne?’ she said, getting to her feet. ‘You touched unwittingly on a delicate subject. I do have a brother, as it happens, but Gabriel is not interested in taking on the estate. He has…’ She searched for the appropriate words. ‘He has other priorities, I fear.’

‘Your father made no mention of a son.’

‘Nor will he,’ she warned. ‘And I beg you to make no reference to Gabriel. It would cause Father the deepest pain. To all intents and purposes, he has no son.’

‘Yet I suspect that you still have a brother?’ he said quietly. Susan Cheever coloured slightly and bit her lip. She took a deep breath. ‘I think that it’s time for you to go, Mr Redmayne.’

Sarah Bale was a woman of bustling energy. Rising shortly after dawn, she cleaned the downstairs rooms, roused her children from their beds, gave them breakfast, took them off to their petty school and, since the weather was fine, returned to make a start on the washing that she took in to supplement the family income. By the time her husband came into the kitchen, she was humming contentedly to herself, her arms deep in a tub of soapy water. Suppressing a yawn, Jonathan crossed to give her a perfunctory kiss of greeting on the forehead.

‘Awake at last, are you?’ she teased.

‘I was late getting back last night, my love.’

‘I know.’

‘Did I wake you?’

‘Only for a moment.’

‘I tried not to, Sarah.’

‘You’re not the quietest man when you move around the house,’ she said, drying her hands on a piece of cloth so that she could turn to him. ‘Your breakfast is all ready, Jonathan. Sit down. You look as if you need it.’

Lowering himself on to a chair, he gave a nod of agreement. The events of the night had turned a routine patrol into a harrowing experience and left him drained. When he climbed into bed, he had fallen instantly asleep. Now, after barely three or four hours, he was up to face a new day. Bread and cheese lay on the platter before him. Sarah put a solicitous hand on his shoulder as she poured him a cup of whey.

‘Did you hear the children?’

‘No, my love.’

‘Then you must have been very tired. They made so much noise this morning, especially Oliver. I had to be very stern with him.’

‘What was the problem?’

‘The usual one,’ she said, putting the jug on the table and sitting opposite him. ‘He didn’t want to go to school. And because Oliver complained, Richard joined in.’

‘School is important. They must learn to read and write.’

‘That’s what I told them.’

‘They don’t understand how lucky they are to be able to have proper schooling. I didn’t at their age, Sarah. My parents couldn’t afford it.’ He took a first bite of bread. ‘I had to pick things up as I went along. My father was a shipwright for thirty years and never learnt to read properly. When I took up the trade, none of the apprentices could even write his own name.’

‘You could, Jonathan. And you’d taught yourself to read the Bible.’

He took a swig of whey. ‘I wanted to be able to read the names of the ships I was helping to build. Knowledge gives you power. You don’t have to rely on others. The boys must realise what an advantage they’ll have in life by being able to read, write and add up properly.’

‘I keep saying that.’

‘Let me have a word with them.’

‘I’d be grateful.’

He addressed himself to his meal and munched away in silence. Pouring herself a cup of whey, his wife sipped it and watched him. Jonathan was gloomy and preoccupied. Sarah could see that something was troubling him but she knew better than to question him too closely about his work. It was a difficult and often dangerous job and he tried to leave it behind whenever he stepped over the threshold. Home was his sanctuary, free from the worries of the outside world. It was a place where he could relax and recover from the strains of his occupation. When he chose to confide in her, Sarah was always willing to listen but she did not prompt him.

She waited patiently until he had cleared his platter. ‘More bread?’ she offered.

‘No, thank you.’

‘I have a fresh loaf.’

‘I can’t stay, my love,’ he said, getting to his feet. ‘I have to pay an early call.’

‘When will I expect you back?’

‘For dinner, I hope. I’ll speak to the boys then.’

‘Good. They listen to you.’

He was about to leave the kitchen when he noticed the quiet concern in her eyes. Feeling that he owed her some kind of explanation, he crossed over to help her up from the table. He pursed his lips as he pondered.

‘I was with Tom Warburton last night,’ he said at length.

‘How is he?’

‘As melancholy as ever.’

‘I wondered where you’d got that grim look on your face.’

Jonathan smiled. ‘Tom is not the most cheerful soul at the best of times. But then,’ he continued, his expression hardening, ‘there was little to be cheerful about. We found a dead body.’

‘Oh dear!’

‘To be truthful, it was Sam who actually found it. Tom’s little dog. He was sniffing around a warehouse near Paul’s Wharf. Just as well, in a way. We’d have walked right past the place and not known the poor devil was there.’

‘Who was he?’

‘I’ve no idea, Sarah. That’s why I’m going to the morgue this morning. To see what I can find out about the man. One thing is certain,’ he said, gritting his teeth. ‘He did not die a natural death.’ He became proprietorial. ‘I don’t like murder in my ward. We have enough ugly messes to wipe up around here without finding corpses as well. This crime needs to be solved quickly. I’ll make sure of that.’

‘Be careful,’ she said, reaching out to squeeze his arm.

‘I always am.’

‘You’re too brave for your own good sometimes.’

He gave a weary smile. ‘The bravest thing I ever did was to ask you to marry me, Sarah, and you were foolish enough to accept. That shows how lucky I am.’

‘Lucky and much loved,’ she said, kissing him. ‘Remember that.’

‘How could I ever forget?’

He gave her a warm hug, then left the room. A minute later, he was leaving the house in Addle Hill to begin the long walk to the morgue. All trace of fatigue was shaken off now. An officer of the law involved in a murder investigation, Jonathan Bale was as alert and zealous as ever.

* * *

Forsaking the safety of travelling companions and anxious to get back to London as soon as possible, Christopher Redmayne rode south at a steady canter. He reproached himself bitterly for causing Susan Cheever dismay with a tactless remark and believed that he had destroyed all hope of a closer acquaintance with her. At the same time, he had elicited an intriguing piece of information about the family. Sir Julius Cheever had three children, one of whom had been his male heir. What provoked him to disown and, presumably, to disinherit his son, Christopher did not know, but it had to be something serious. Susan, by contrast, had not discarded her brother and he was bound to wonder if the two of them were still in contact. Clearly, it was a source of dispute between father and daughter. He came to understand Sir Julius’s suppressed anger a little more. The death of his wife and the estrangement of his son were personal sorrows to be added to the profound distaste he felt for the Restoration and its consequences. The sense of loss was unendurable. It soured him. Sir Julius would be a fiery and malcontented Member of Parliament.

He might also be a cantankerous client. Christopher accepted that. There were consolations. Not only had the young architect secured a valuable commission to design a house in London, Sir Julius had insisted on giving him a generous down-payment in cash to encourage him. The money was safely stowed away in Christopher’s satchel along with the preliminary drawings he had made. There was an additional feature that brought him particular pleasure. This was the first major project he had won entirely on his own merit. His brother, Henry, had been instrumental in finding him his first three clients and, though one of the houses was never actually built, the two mansions that were completed served as a lasting tribute to his talent. By comparison with these undertakings, the design of a new bookshop for Elijah Pembridge was a relatively simple affair that had brought in much-needed money but would hardly enhance his reputation. For that reason, he did not list it among his achievements. Henry Redmayne had been indirectly responsible for that commission as well but he had no connection whatsoever with Sir Julius. Much as he loved his brother, Christopher was grateful to be striking out on his own at last.

Susan Cheever had been right. Northamptonshire was a beautiful county. In the hectic dash north, Christopher had not taken the trouble to admire the scenery on the way. Now, with two days of hard riding ahead of him, he determined to repair that omission. Heavily wooded in some areas, Northamptonshire was given over almost exclusively to agriculture. The soil was rich but less than ideal for ploughing and grain production, so there was a predominance of dairy farming and sheep-rearing. Herds of cattle and flocks of sheep seemed to be everywhere. Christopher passed the occasional windmill as well. What he noticed was the absence of any major rivers. Since it was largely denied direct access to the sea by means of navigable water, Northamptonshire was curiously isolated. The lack of a major road through the heart of the county was another element that set it apart from its neighbours. On the first stretch of his journey, Christopher was travelling along a small, winding, rutted track. It was only when he crossed the border into Bedfordshire that he found a wider and more purposeful road.

Not long after noon, he stopped at an inn for refreshment. The Jolly Shepherd was a welcoming hostelry that offered good food and strong drink to its customers. A large party of travellers, all men, occupied three of the tables. Christopher found a seat in the corner and sampled the game pie, washing it down with a tankard of beer. A tall, bearded, well-dressed man in his thirties sauntered across to him with an easy smile.

‘May I share your table, my friend?’ he asked.

‘Be my guest,’ said Christopher pleasantly.

‘I’m much obliged, sir.’ The man sat opposite him and set his own tankard down. ‘It’s rather quieter at this end of the room. Our fellow travellers are in raucous mood.’

Even as he spoke, a jesting remark set the entire party roaring in appreciation. Judging by the amount of food and drink in front of them, they would be there for some time. They were patently making the most of their stop.

‘Where are you heading?’ asked the man.

‘London,’ said Christopher.

‘So are our noisy neighbours. Fall in with them and you’ll have a safer journey.’

‘I’ll make better speed on my own, I think.’

‘Do you have a good horse?’

‘An excellent one.’

‘Then I’ll bear you company part of the way, if I may,’ offered the other. ‘My home is near Hertford. Could you tolerate me alongside you until then?’

‘I believe so.’

The man beamed. ‘That settles it.’ He extended a hand. ‘Zachary Mills at your service.’

‘Pleased to make your acquaintance, sir,’ said Christopher, shaking his hand. ‘My name is Christopher Redmayne.’

‘Have you ridden far?’

‘I had business in Northamptonshire.’

‘Ah, so did I, Mr Redmayne. Sad business, as it happens. I was visiting my sick mother in Daventry. She is desperately ill but I like to think that I helped to sustain her while I was there. The doctor holds out little hope.’

‘I’m sorry to hear that.’

‘It comes to us all,’ said Mills resignedly. He brightened at once. ‘But I’ll not burden you with my family problems. I’m so relieved to spend some time on the road with a gentleman. Some of these fellows,’ he added, nodding in the direction of the three full tables, ‘have yet to learn proper manners.’ Another roar went up as a more uncouth jest was passed around. ‘Do you take my point?’

‘I do, Mr Mills.’

‘I could see that you would.’

Zachary Mills was a pleasing companion, urbane, well-spoken and attentive. When he had ordered his own meal, he insisted on buying Christopher a second tankard of beer. The conversation was confined to neutral subjects and Mills made no attempt to pry into Christopher’s personal affairs. The latter was grateful for that and glad that he would have someone to share the next stage of the journey. In the event of attack from highwaymen two swords were better than one, and Mills had the air of a man who knew how to use his blade. As time passed, however, the rowdiness increased among the other travellers and the two men left by tacit consent. They strolled towards the stables, talking amiably about the advantages of living in London, a city that Mills seemed to know extremely well. He had a sophistication that had been notably lacking among the other guests at the inn. Christopher warmed to him even more.

When they entered the stables, however, Mills’s manner changed at once. Putting a hand in the small of Christopher’s back, he pushed him so firmly that the latter stumbled to the ground. Christopher was on his feet at once, swinging round to face the other man and ready to demand the reason for the unwarranted shove. He found himself staring down the barrel of a pistol and his question was answered. The plausible friend was a cunning robber. Mills gave him a broad grin.

‘You should have stayed with the others, Mr Redmayne. Safety in numbers.’

‘I took you for a gentleman.’

‘Why, so I am, good sir.’

‘Indeed?’

‘I extend every courtesy to the people I rob.’

Christopher was sarcastic. ‘What would your sick mother say?’

‘She’s in no position to say anything, alas. She died several years ago.’

‘Out of a sense of shame at her son, no doubt.’

‘Do not vex me, Mr Redmayne,’ cautioned the other. ‘This pistol is loaded. All you have to do is remove that satchel and hand it over with your purse. I’ll then be obliged to bind and gag you while I make good my escape. By the time that drunken crowd stumble out here and find you, I’ll be well clear.’

‘How will you tie me up?’

‘I have rope in the saddlebags directly behind you.’

Christopher glanced over his shoulder. ‘I see that you planned this very carefully, Mr Mills,’ he said with grudging respect.

‘I leave nothing to chance.’

‘That remains to be seen.’

‘I’d advise against any futile heroics.’

‘I’ll remember that,’ said Christopher, weighing up the possibilities of escape. They were severely limited. ‘May I ask why you singled me out?’

‘The satchel gave you away, I’m afraid.’

‘Did it?’

‘Yes, my friend. In all the time we were at the table, you never once took it from round your neck. That means it contains something valuable.’

‘It does. Something that I’ll not part with easily.’

‘Gold?’

‘Drawings.’

Mills was sceptical. ‘Drawings?’

‘Correct, sir.’

‘I’ve no time to play games, Mr Redmayne.’

‘It’s the truth. I’m an architect by profession and I’ve been visiting a client who wishes me to design a new house for him.’ He patted his satchel. ‘The preliminary sketches are in here. They’d be worthless to you and it’s vital that I keep them.’

‘That satchel contains more than a few drawings,’ said Mills, levelling the pistol at him. ‘Hand it over or I’ll be forced to take it from your dead body.’

Christopher shrugged. ‘If you insist.’

‘I do.’

‘Then first let me prove that I’m a man of my word – unlike you, I may say.’ Christopher opened the satchel to take out a piece of folded parchment. ‘Here, see for yourself. A town house in the Dutch style, commissioned by Sir Julius Cheever.’

Mills took the parchment and flicked it open to glance at the various drawings. They were neat and explicit but he was still unconvinced. The pistol was turned in the direction of the satchel.

‘I’ll wager there’s something else in there, Mr Redmayne, or you’d not have been nursing it like a baby throughout dinner. I’m wondering if this illustrious client of yours might not have given you some money on account. Is that what’s in the satchel?’

‘Alas no!’ sighed Christopher. ‘But have it, if you must.’

He slipped an arm through it and lifted the strap over his head. Mills glanced down at the drawings in his hand. It was a fatal mistake. Christopher moved at lightning speed, hurling the satchel into his face and diving straight at him, knocking him against one of the stalls with such force that the pistol dropped from his hand. It was no time for social niceties. Grabbing his adversary by the throat, Christopher pounded his head against the stout timber. Mills cursed, struggled and kicked but he was up against someone stronger and more determined. Christopher was annoyed at himself for being duped and that gave him extra power. When Mills tried to pull out his dagger, Christopher hurled him to the ground and stamped on his wrist until the weapon slid uselessly away. The commotion had upset the horses and they neighed in alarm, shifting in their stalls as the two men grappled together on the straw-covered floor.

It was when Mills’s flailing body squirmed on to the drawings that Christopher really lost his temper. They were only early sketches but they represented something very important in his life and he was not going to have them treated with disrespect. With a burst of manic energy, he sat astride his opponent and subdued him with a relay of punches to the face, ignoring the pain in his knuckles until Mills lapsed into unconsciousness. Breathing heavily and with bruises of his own from the fight, he hauled himself to his feet. His first priority was to secure and silence the other man. When he found the rope in the saddlebags he used it to bind Zachary Mills to a solid oak post, then took out the latter’s own handkerchief to use as a gag. Though his first instinct was to deliver the man up to the local constable, he saw the drawbacks. It would mean an interminable delay as he tried to explain what had happened and Mills would assuredly contest his version of events. Pain and humiliation would be the highwayman’s punishment. Trussed up tightly and covered in blood, he would have time to repent of his folly in choosing the wrong victim. It might be hours before he was discovered and released by the departing travellers. Christopher would be in the next county by then.

Slipping the satchel over his shoulder, he recovered the pistol and dropped it in with the money from Sir Julius. He then picked up the parchment with the drawings on it and smoothed it out reverently. When Mills opened a bloodshot eye, Christopher showed no sympathy for him. He held up the parchment.

‘You shouldn’t have creased this,’ he said. ‘My drawings mean everything to me.’

CHAPTER THREE

Dead bodies held no fears for Jonathan Bale. He had looked on too many of them to be either shocked or revolted. Those dragged out of the River Thames were the worst, grotesque parodies of human beings, bloated out of all recognition and, when first hauled from the dark water, giving off a fearsome stink. The corpse that lay on the stone slab in the morgue was neither grossly misshapen nor especially malodorous. Wounds were minimal and the herbs liberally scattered in the cold chamber helped to smother the stench of death. Jonathan watched over the shoulder of the surgeon as he examined the body that had been found at Paul’s Wharf on the previous night. He was struck by how peaceful the face of the deceased looked, less like that of a murder victim than someone who had passed gently away in his own bed.

‘Interesting,’ said the surgeon, peering at the cadaver’s neck.

‘What have you found, sir?’ asked Jonathan.

‘I’m not sure.’

‘He’s so young to die.’

‘Still in his twenties, I’d say. Young, healthy and well muscled.’

Jonathan nodded. ‘What a cruel waste of a life!’

Ecclestone continued his detailed inspection by the light of the candles. He was a small, thin, agitated man in his fifties with colourless eyes and a skin so pale that he might have climbed off one of the slabs in the morgue. A chamber of death was his natural milieu and he had divined most of its secrets. While the surgeon shifted his attention to the naked chest, Jonathan made his own appraisal. The young man had been undeniably handsome in life, the long brown hair well groomed and the carefully trimmed beard hinting at vanity. Smooth hands and clean fingernails confirmed that he was a stranger to any manual labour. There was an ugly red weal around his neck and bruising beneath his left ear. What looked like more bruises showed on the chest and stomach. Only one puncture wound was visible, close to the heart. The man’s head lolled to one side. His cheeks had a ruddy complexion.

After a thorough examination, Ecclestone stood back and clicked his tongue.

‘Well?’ said Jonathan.

‘He was strangled to death, Mr Bale.’

‘I thought he was stabbed through the heart.’

‘He was,’ agreed Ecclestone, ‘but only after he was dead. That’s why there was so little blood. When death occurs, the circulation of the blood ceases.’

‘Why stab a dead man?’

‘To make absolutely sure that he was dead, I imagine.’

‘The murderer took no chances,’ noted Jonathan gruffly. ‘He not only strangled and stabbed the poor fellow, he beat him about the body for good measure.’

‘What makes you think that, Mr Bale?’

‘Look at those bruises, sir.’

‘That’s exactly what I have done.’ He squinted up at the constable. ‘You were one of the men who found him, I understand.’

‘That is so.’

‘Then I’ll warrant he was face down at the time.’

Jonathan was impressed. ‘Why, so he was.’

‘And had been for a little while, if my guess is correct.’ He pointed a stick-like finger. ‘Those are not bruises you can see, Mr Bale. When the blood stops being pumped around by the heart, it gradually sinks to the blood vessels in the lowest part of the torso. In this case, to the chest and stomach, which have a livid hue. After a certain amount of time, the purplish stains become fixed and take on the appearance of large bruises. I’ve seen it happen so often. No,’ decided Ecclestone, gazing down at the corpse once more, ‘I suspect that death was swift, if brutal. Someone took him unawares and strangled him from behind, putting a knee into the small of his back as he did so. If you turned him over, as I did before you came in, you’d see the genuine bruise that’s been left there.’

‘I take your word for it, sir.’

Ecclestone was brisk. ‘So, the cause of death has been established. My work is done. It’s up to others to discover the motive behind the murder.’

‘It could hardly be gain,’ argued Jonathan. ‘There were valuable rings on his fingers and money in his purse.’

‘It was fortunate that you came along before anyone else found him.’

‘I know.’

‘Do you have any notion who he might be?’

‘None, sir. There was no means of identification on him.’

‘Hardly an habitué of Paul’s Wharf, that’s for sure.’

‘Quite,’ said Jonathan. ‘You won’t find a suit of clothes as costly as that being worn in a warehouse. He’s a gentleman of sorts with a family and friends who’ll miss him before long. Someone may soon come forward.’

‘And if they don’t?’

‘Then we’ll have to track his identity down by other means.’

‘Do you have any witnesses?’

‘Not so far, sir. My colleague, Tom Warburton, is making enquiries near the murder scene this morning. When I spoke to him on my way here, he had had no success. It was late when we found the body. The wharf was deserted at that time of night. We are unlikely to find witnesses.’

‘What was a man like this doing in such a place?’

‘I don’t think that he went there of his own accord, sir,’ said Jonathan solemnly. ‘I begin to wonder if he was killed elsewhere then dumped near that warehouse.’

‘Why do you say that?’

‘Because of the state of his apparel. When we found him last night, the back of his coat was covered in dirt, as if he’d been dragged along the ground by someone. There were a few stones caught up in the garment.’ He took them from his pocket to show them to the surgeon. ‘Do you see how small and bright they are, sir? You won’t find any stones like this in the vicinity of the warehouse.’

‘You’ve a sharp eye, Mr Bale.’

Jonathan put the stones away again. ‘These may turn out to be useful clues.’

‘I hope so. Well,’ said Ecclestone, pulling the shroud over the corpse, ‘I’ve told you what I’ve seen. A young man cut down in his prime by a sly assailant. A powerful one, too. The deceased would have fought for his life. Even with the element of surprise in his favour, only a strong attacker could have got the better of him.’

‘Unless he was groggy with drink.’

‘I detected no smell of alcohol in his mouth.’

‘Oh.’

‘You can rule that out.’ The surgeon turned and walked out of the morgue. Jonathan followed him, glad to quit the dank and depressing chamber. When they stepped out into the fresh air, he took several deep breaths. Ecclestone paused to stare up at him.

‘Is there anything else that I can tell you, Mr Bale?’ he asked.

‘No thank you, sir. You’ve been very helpful.’

‘This was no random murder.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘It did not happen by accident on the spur of the moment. If you or I wished to strangle someone, we’d never do it as quickly and efficiently as that. Do you hear what I’m saying, Mr Bale?’

‘I believe so. It was not the work of an amateur.’

‘Exactly. This man has killed before. Often, probably.’

‘A hired assassin?’

‘Certainly not a person to turn your back on.’ He licked his lips and closed one eye. ‘You said earlier that you’d have to find out the victim’s identity by other means.’

‘The search will begin this very morning, sir.’

‘Where?’

‘Among the most exclusive shoemakers in the city.’

‘Shoemakers?’

‘Yes,’ said Jonathan, producing the shoe that had been picked up at the wharf by an inquisitive dog. ‘I want to find out who sold him this.’

‘What happened to you, Mr Redmayne?’ said Jacob in alarm. ‘Your face is bruised and your coat is torn. Is that blood on your sleeve?’

‘Yes, Jacob,’ said Christopher, putting his satchel down and removing his coat, ‘but you’ll be pleased to know that it’s not mine. A highwayman made the mistake of trying to rob me and had to be put in his place.’ He flexed both hands. ‘My knuckles still hurt from the fight.’

The servant blenched. ‘A highwayman?’

‘Don’t worry. I learnt my lesson. On the following day, I put safety before valour and joined a party of travellers on their way to London. It slowed me right down but gave me an opportunity to nurse my wounds. I spent the second night at an inn with my companions. And here I am,’ he announced, spreading his arms. ‘Home again, with no harm done.’

‘I wouldn’t say that,’ argued Jacob, inspecting his master’s coat. ‘How on earth did you get involved with a highwayman in the first place?’

‘Because I was reckless.’

‘That’s a kind word for it, sir.’

‘I’m in the mood for kind words. Remember that.’

Christopher sat down at the table, and Jacob disappeared into the kitchen with the coat. When he came back, he brought a glass of brandy on a tray. Giving him a nod of gratitude, Christopher took the glass and sipped its contents.

‘You sensed my needs exactly, Jacob,’ he said.

‘That’s what I’m here for, sir.’