8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Verve Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

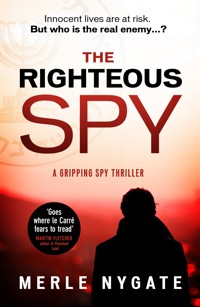

Innocent lives are at risk... but who is the real enemy?

Eli Amiran is Mossad's star spy runner and the man responsible for bringing unparalleled intelligence to the Israeli agency. Now, he's leading an audacious operation in the UK that feeds his ambition but threatens his conscience.

The British and the Americans have intel Mossad desperately need. To force MI6 and the CIA into sharing their priceless information, Eli and his maverick colleague Rafi undertake a risky mission to trick their allies: faking a terrorist plot on British soil.

But in the world of espionage, the game is treacherous, opaque and deadly…

A twisting international spy thriller, A Righteous Spy is an intriguing tale of espionage that portrays a clandestine world in which moral transgressions serve higher causes. A must-read for fans of Homeland, Fauda and The Americans, it will also appeal to readers of Charles Cumming and John le Carré.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 515

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

THE

RIGHTEOUS

SPY

MERLE NYGATE

VERVE BOOKS

Table of Contents

Title Page

To | DN and WG | Always

PART 1 – THE CHOSEN

1 | Palestinian Territories – Present Day

2 | Tel Aviv, Israel – The Same Day

3 | King Solomon Street, Tel Aviv – Ten Minutes Later

4 | The Office, Tel Aviv – Thirty Minutes Later

5 | The Office, Tel Aviv – Thirty Minutes Later

6 | Old Street, London – A Week Later

7 | Palestinian Territories – Two Weeks Later

8 | Swiss Cottage, London – The Same Day

9 | Thames End Village, Surrey – Later that Day

10 | The Israeli Embassy, Palace Gardens, London – The Next Day

11 | Thames End Village Station, Surrey – The Next Day

12 | Heathrow Airport, London – Two Days Later

13 | M40 Motorway – Four Days Later

14 | The Six Horseshoes Pub, Cheltenham – The Next Day

15 | West Kensington, London – The Next Day

16 | West Kensington, London – Thirty Seconds Later

17 | M25 Motorway – Two Days Later

18 | Summertown, Oxford – The Next Day

19 | Summertown, Oxford – Nine Hours Later

Part 2 – THE RIGHTEOUS

20 | Watlingford Public School, Oxfordshire – One Week Later

21 | Herzylia, Israel – The Same Time

22 | The Israeli Embassy, Palace Gardens, London – The Next Day

23 | Paddington, London – Three Days Later

24 | Birmingham, Three Days Later

25 | M40 Motorway – The Same Day

26 | Thames End Village, Surrey – Same Day

27 | Pall Mall, London – The Next Day

28 | The Israeli Embassy, Palace Gardens, London – Fifteen Minutes Later

29 | Watlingford Public School, Oxfordshire – The Next Day

30 | Bayswater, London – The Next Day

31 | West London – The Same Evening

32 | Westbourne Grove, London – The Next Day

33 | Stall Street, Bath – Two Days Later

34 | Abingdon, Oxfordshire – The Next Day

Part 3 – THE DELUDED

35 | The Israeli Embassy, Palace Gardens, London – The Next Day

36 | The Six Horseshoes Pub, Cheltenham – The Next Day

37 | M40 Motorway – One Hour Later

38 | The Israeli Embassy, Palace Gardens, London – Three Hours Later

39 | Marylebone High Street, London – The Next Day

40 | Watlingford Public School, Oxfordshire – Three Hours Later

41 | Watlingford Public School, Oxfordshire – The Same Evening

42 | M40 Motorway – The Next Day

43 | West Hampstead, London – The Next Day

44 | Hyde Park Corner, London – Five Minutes Later

45 | St John’s Wood, London – Five Hours Later

46 | Hanway Street, London – One Hour Later

47 | All Saints Road, Cheltenham – Early Next Morning

Part 4 – THE DEATH

48 | Watlingford Public School, Oxfordshire, Classroom, The Next Day

49 | Watlingford Public School, Oxfordshire – At The Same Time

50 | Watlingford Public School, Oxfordshire – One Hour Later

51 | Watlingford Public School, Oxfordshire – The Next Day

52 | The Ironworkers Pub, Cowley, Oxfordshire – The Next Day

53 | The Ironworkers Pub, Cowley, Oxfordshire – Continuous

54 | The Israeli Embassy, Palace Gardens, London – The Next Day

55 | Watlingford Public School, Oxfordshire – The Next Day

56 | Watlingford Public School, Oxfordshire – The Same Day

57 | RAF Fairborough, Oxfordshire – Ten Minutes Later

58 | RAF Fairborough, Oxfordshire – Five Minutes Later

59 | RAF Fairborough, Oxfordshire – Three Minutes Later

60 | RAF Fairborough, Oxfordshire – 11 Minutes Later

61 | RAF Fairborough, Oxfordshire – Three Minutes Later

62 | RAF Fairborough, Oxfordshire – Five Minutes Later

63 | Techno Zone, RAF Fairborough – Three Minutes Later

64 | Techno Zone, RAF Fairborough – The Same Time

65 | The Aviation Club, RAF Fairborough – Two Minutes Later

66 | Techno Zone, RAF Fairborough – Ten Seconds Later

67 | The Aviation Club, RAF Fairborough – Three Seconds Later

68 | RAF Fairborough, Exhibitors’ Caravan Site – 10 Minutes Later

69 | Ramat Gan, Tel Aviv – A Month Later

70 | Thames End Village, Surrey – Two Weeks Later

71 | Queen’s Park, London – Two Weeks Later

72 | The Travellers Club – Next Day

73 | Queen’s Park, London – A Week Later

Author’s Notes

Book Club Questions

Acknowledgements

About the Author

To

DN and WG

Always

PART 1 – THE CHOSEN

But God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise; God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong.

1 Corinthians 1:27

––––––––

For you are a people holy to the Lord your God and the Lord has chosen you to be a people for his treasured possession, out of all the peoples who are on the face of the earth.

Psalm 50:15

––––––––

This day have I perfected your religion for you and completed My favour upon you and have chosen for you Islam as your religion.

Quran 5:3

1

Palestinian Territories – Present Day

Soon.

I know it’ll be soon because when we finished prayers this morning Abu Muhunnad’s eyes were shiny; and I don’t think it was irritation caused by dust and the wind that blows sand from the south.

It was not as if it was anything he said, I just had the sense that he wasn’t listening when I told him about my fast, at least not as intently as he usually does. I was describing the verse I’m reading and instead of commenting, he just nodded. That’s when I saw his eyes glitter with tears.

I’m okay. Really, I am.

I wanted to say that to Abu Muhunnad this morning. I wanted him to know and be certain that I am truly filled with joy and grateful for the opportunity, inshallah. It’s as if everything I’ve done in my twenty-seven years has led me to this point, this place, this precise moment in time where, finally, I am going to make a difference.

2

Tel Aviv, Israel – The Same Day

Seventy kilometres away – as the drone flies – Eli Amiram made his way to the bus stop for his morning commute. Even though he’d strolled only a short distance, from apartment to bus stop, by the time Eli arrived at the shelter he was sweating. His shirt grazed his damp neck and he could smell shower soap, deodorant and his own perspiration. The middle of May and at 7am, the temperature was already hitting 28 degrees. But the heat in isolation was nothing. Humidity was the killer; the wet, dense air that trapped him in its steaming strait-jacket. Eli leaned against the side of the metal bus shelter and narrowed his eyes. He tried to imagine grey London streets underfoot, grey clouds above and what it might feel like to inhale, if only for a second, cool air that hadn’t been artificially refrigerated. It was too bad Gal had driven north to see her mother. Otherwise, he’d have been in the car looking out, not on the street, sweating like an animal.

Half a metre away a woman was shrieking into her cell phone. Eli closed his eyes. He stroked the top of his shaved head and felt the new growth on his skull. He supposed it could have been worse; at least the Khamsim was over. As far as Eli was concerned, a hard blue sky and 90 per cent humidity was a distinct improvement.

After a few more seconds of being bombarded by the woman’s conversation Eli opened his eyes to assess the source of the voice. What he saw was a fleshy face with faded blonde hair brushed back into a bun. He knew the type. The pitch of the woman’s voice was bad enough, but her heavily accented Hebrew set Eli’s teeth on edge. It was like listening to Stockhausen’s Helicopter String Quartet.

The bus screeched to a halt and Eli peeled his back away from the bus shelter and let the grandmother lumber ahead of him. Hauling herself aboard she found a seat halfway down the aisle. Eli made his way to an empty seat at the back of the bus; it was well away from the grandmother but next to a dati. Sliding down, Eli glanced over at the grey side burns, wispy beard and pallid skin.

The bus jolted forward and Eli’s head jerked back against the headrest. He felt a finger nudging his ribs. Turning, Eli caught a blast of a gastric disorder from the man’s mouth.

‘You speak English?’ the old man said with an American accent. ‘Or Yiddish?’ His tone was peremptory and he didn’t wait for an answer. ‘Is this Rosh Pinna Street? Is this the corner of Rosh Pinna and Ariel?’

‘Next stop,’ Eli said.

‘You’ll tell me when we get there?’

‘Of course, it’ll be a pleasure.’ Aware that he’d used the right idiom Eli was still irritated with himself because he always struggled with the precision and physical placement of an English accent. The focus wasn’t around the lips and vestibule of the mouth like French, neither was it located near the hard palate and throat like Arabic. It sat somewhere around the middle, just before the soft palate and it bugged him that he hadn’t got it. Even after years of study.

Five minutes later, when Eli was still trying to select an appropriate expression to practise on the American, they were at Rosh Pinna Street. Eli stood to let the man out.

‘Take your time, sir,’ Eli said. ‘There’s no rush, no rush at all.’ Shit. He’d done it again. Rolled the ‘r’. As he sat down, Eli grimaced trying to achieve the oral position for a non-rolling ‘r’.

That was when he noticed a new passenger, a woman, step into the body of the bus.

Eli stared. In dark blue jeans and flowing green top, skeletal shoulders sat atop a lumpy waist and an ugly hat shaded her face. But it wasn’t the absence of any aesthetic that made the base of Eli’s neck prick as if an elastic band had flicked against his flesh; it was her expression – she was terrified.

Eli glanced across the aisle at a soldier to see if his combat receptors had kicked in but the kid was more interested in the horse-faced girl by his side. No back-up there.

Up ahead, the woman was hauling a black and white shopping trolley down the aisle. Judging by her strained expression the load was heavy. Eli stood up to get a better look at her.

Was she ill?

Beneath heavy make-up the woman was pouring sweat. She was drenched. A slick of moisture dewed her upper lip and the armpits of the blouse were almost black. Okay, it was hot outside and okay, she’d dragged a loaded shopping trolley to the bus stop, but there was something wrong with her. Between thick eyebrows there was a deep frown crease and her eyes flicked around the bus, not settling, not making contact.

Eli reached into his pocket for his cell phone. He glanced down and fingered the button to call the emergency services. Was he over-reacting? Up ahead he saw the woman’s lips were moving and her hand was clenched around the handle of the shopper.

She’d found a seat. Right in the middle of the bus. Right where a device would cause the maximum damage. She sat down and Eli got a good view of her back and the narrow profile of her shoulders atop the billowing green top. Her waist was out of proportion to the rest of her body and she was holding on to that damn shopper as if her future depended on it.

‘Slicha, excuse me,’ Eli slid out from his seat and shoved aside a kid standing in the aisle reading his phone.

Ahead, the woman was still clutching the shopper and positioning it with both hands. Not one. Struggling to keep it upright. Eli was two metres away from her and closing in when a man, an office worker in a white shirt, stepped into the aisle and blocked Eli’s way. In one hand he had a paper cup of coffee and he was reaching to take a linen jacket off the seat hook with the other. Using the flat of his hand against the man’s chest, Eli pushed him back into his seat. The coffee went flying as the office worker lost his balance and fell on top of another man reading a newspaper.

‘What the fuck!’

Eli didn’t look back.

The bus grunted to a halt and the brakes squealed. The doors hissed open. Eli reached the woman and wrenched the shopper from her grip. He glimpsed the fear in her eyes. Behind him people stood about to get off. Eli blocked them. He ripped open the Velcro cover of the shopper and dove inside. He pulled out a nightdress and a toilet bag and tossed them across the floor of the bus where they skittered under the seats.

‘What’s going on? What’s happening, why can’t we get off?’ Sharp and anxious voices. Voices close to panic. Meanwhile, Eli plunged his hand deeper into the shopper again and again but found only softness; no wire, no block, no bomb. In his peripheral vision Eli saw the soldier boy holding back the passengers.

‘What’s happening? Is there something wrong?’ Eli heard from the crowd of commuters.

‘Bitachon, security,’ Eli said. ‘Everything’s under control.’

Now on his feet Eli dragged off the woman’s hat. Tear tracks striated the make-up on her face.

‘Are you out of your mind? What do you think you’re doing?’

That voice, that awful accent, it was the grandmother sitting right next to the girl Eli had just assaulted.

‘I had reason to believe –’ Eli tried to make his voice sound authoritative hoping that a firm tone would camouflage his cock-up.

Her face was red and one of her dockworker’s arms was around the girl’s skinny shoulders.

‘Didn’t the good Lord give you eyes in your stupid big head? The girl’s sick, she’s going to the hospital and she’s frightened to death.’

‘Lady, we all have to be vigilant and aware of security at all times. D’you understand? Okay, I made a mistake, I apologise, but I was acting in the best interest of everybody.’

There were rumblings from the other passengers. They were divided. Eli saw the man with a coffee stain across his white shirt; he nodded at Eli. He got it. He understood. But the grandmother didn’t.

‘What kind of idiot are you?’

He hissed, ‘The kind of idiot who is trying to protect you from being blown to pieces. Do you have a problem with that?’

‘Maspeek, enough, please,’ whispered the girl through tears. ‘It’s okay, I’m okay.’

‘Lady, I’m sorry, I made a bad mistake,’ Eli grabbed a handful of clothes from the floor and dumped them on the girl’s lap. Then, since the soldier boy was still holding back the rest of the passengers, Eli scrambled down the steps on to the street.

He walked the rest of the way to the Office.

3

King Solomon Street, Tel Aviv – Ten Minutes Later

Eli stepped through a set of automatic doors into the blessed chill of the downtown mall. It was a relief. The incident on the bus was unfortunate but defensible. Eli strode past the small café where the gym bunnies hung out. As usual, he pulled in his gut. Next, he passed a branch of Bank Leumi and a small supermarket with a metal turnstile and cliffs of cut-price vodka. Finally, Eli reached the northwest corner of the mall and a scuffed metal door that bore no sign. As he did every office day, Eli curled his right hand around the vertical handle and contacted the fingertip recognition keypad. Hand in position he looked around the mall, checking to see if there was anyone nearby. It was unnecessary as there were cameras everywhere but it was procedure. It’s what you did; it’s what you were trained to do.

Periodically refurbished and updated, this particular Mossad facility was located in a building within another building. It had its own generators, electronics and water supplies, communications, cryptography and the rest of the technical tricks department. While Eli visually swept the mall, his vital signs were being monitored, fed into the computer system, compared to a set of algorithms and minutely measured to see whether he was unusually stressed or unusually unresponsive.

The door clicked open and Eli slid into the first security section where he handed in his home cell phone to the staff behind the desk and had a further retinal identification check.

As always, Eli was struck by how quiet it was when the door to the mall shut behind him. It wasn’t just a door – it was a boundary; like walking from the beach into the sea to take that first breath through the snorkel into another world. Here the atmosphere was sterile; the only colour was the lights from the bank of monitors against the white wall; the only sound, apart from human voices, was the hush and hum of electronics. Beyond the reinforced door, the mall shrieked with its discordant colours, tinny music and neon pleas to purchase.

Eli assumed his easy, affable, professional face. The one he used in the field, when he didn’t want to share his thoughts.

‘Good morning one and all,’ Eli said.

‘Morning Eli,’ Ze’ev, a curly haired blond boy didn’t look up from the machine that was scanning Eli. ‘See the game last night? Disaster.’

‘There’s only one team worth talking about; Maccabi Tel Aviv is and always has been the best.’

Ze’ev glanced away from the scanner to roll his eyes while a young woman stepped out from behind the desk and ran a second, hand scanner over Eli who stood with his legs apart and arms above his head.

Pronounced clean, Eli made his way through two more double doors to the lift and the second-floor canteen.

The canteen was modern with pale wood, stainless steel and deftly placed mirrors to give the illusion of light even though the space was enclosed by metres of blast-proof concrete. There were a few windows in Mossad’s central Tel Aviv building, but those were on the upper floors where department heads had their offices, not in the 24-hour canteen where everybody ate, from the cleaners to intelligence analysts to signal collectors, to the tech geeks, to the shrinks. The single canteen was a nod to the dim memory of kibbutz life where the cow-shed worker sat next to the nursery nurse who sat next to the kibbutz administrator.

Pushing the wooden door open, Eli caught the scent of fresh coffee. He also spotted Rafi sitting on one of the blue plastic chairs right near the coffee station.

Eli joined the queue at the pastry station for a Bulgarian cheese boureka and kept his back to Rafi to avoid eye contact. It had been four short weeks since Rafi had been let loose on the mid-Africa desk; and already he’d created something of a stir in the office. Maybe it was his leather biking jacket and white tee shirts but apparently the girls in Collections had coined a name for Rafi: ‘movie star’. Eli wondered if they had a name for him too. Best not to think too hard about that.

The server gave Eli the hot pastry wrapped in greaseproof paper. Walking towards the coffee station, Eli kept his eyes locked straight ahead as if he was lost in some meditative thought.

‘Eli, my main man,’ Rafi called over in mid-Atlantic English. ‘A’hlan,’ he continued in street Arabic, and finally in Hebrew, ‘Eli, sit for a moment, great to see you. So, tell me, what’s going on with Red Cap? I just read the London signal in the summary. Looks pretty serious to me. For this to happen two weeks after the passport fiasco in London...’

Using an outstretched leg, Rafi pushed out one of the blue chairs. It was an invitation to sit down; Eli remained standing and with deliberation helped himself to the coffee at the dispenser.

‘Patience, Rafi,’ Eli said. ‘As Tolstoy said, the two most powerful warriors are patience and time.’

4

The Office, Tel Aviv – Thirty Minutes Later

By the time that Eli stepped into the meeting room he’d worked out both tactics and strategy for dealing with Red Cap.

It was no big deal. Just a manifestation of the perennial problem with agents: you might even say it was ‘the nature of the beast’. Pondering the provenance of the English idiom, Eli settled himself in his usual chair with his back against the wall. In keeping with the organisation’s current culture, there was no magisterial boardroom table down the middle of the meeting room and no refreshments either. Just a few Ikea side tables stacked for convenience and you brought in your own coffee.

While Eli waited for Yuval to arrive he massaged his eyebrows with thumb and middle finger. In spite of Rafi’s gleeful anticipation that the Red Cap fallout would spatter in his direction, Eli was sanguine. He was not about to get wound up by this new guy’s attempt at dramatisation and disruption.

Eli checked his watch and on cue, 0800, Yuval marched into the room. About the same height as Eli, or perhaps a little shorter, Yuval was dark. In the field he passed himself off, with some success, as Spanish. Thick black hair flopped over his forehead and he repeatedly and impatiently pushed back the fringe with one of his small nail-bitten hands.

In the style of a platoon leader briefing his squad, Yuval picked up the remote control and activated the screens. The logo and motto of Mossad came up and the representatives of the fourteen operational desks sat up to attention. There were no preliminaries, no chit-chat, no social niceties. Yuval was direct and interrogatory. Each day at 0800 and ten seconds for the last three months, he’d circumnavigated the room in the same order, starting with aleph – for Africa.

‘The situation is like this,’ Yuval started. ‘We have a special operation underway in Nairobi,’ Yuval punched out the words while his eyes pecked at his audience. ‘The target has now been located and identified. There’s been subsequent verification by two independent witnesses. We’re only waiting for the prime minister’s authorisation before we go. Rafi, this is your desk, do you have anything to add?’

Rafi stood up and took charge of the remote control and an image of a thick-set, suntanned man with unnaturally white teeth appeared on the screen. He was crinkling his eyes against bright sun and in the background there was blurred blue sea.

‘This is Klondyke,’ Rafi said. ‘An ex-pat, ex-army British major with homes in Barbados and Switzerland. Founder member of an organisation called 91, dedicated anti-Semite, racist, colonialist, funder of any racist group, political or otherwise, who happen to have their feedbags out, and all-round good guy. For a day job he is the main supplier of military spares to Al Shabab and Hamas’s long-time go-to man for quality detonators. Recently he’s been looking to trade up and invest in laser technology which, on top of everything else, makes him a target.’

Then Rafi reeled off the resources that had been made available for the operation, the estimated time of completion, the training hours the squad had completed and the three fall-back plans.

Eli was uncomfortably impressed. He uncrossed his legs and leaned forward, elbows on knees. All the facts and figures tripped off Rafi’s tongue and as he held the floor Yuval’s head bobbed in tiny movements of comprehension and approval.

Rafi went on, ‘As discussed on Friday and signed off, the tactical decision is for the squad to use a location five K from the contact point.’

‘Are they going to rehearse access in situ?’ Yuval said.

The subtext in the simple question was clear. No mistakes would be tolerated.

Rafi said, ‘No. They’ve done timed rehearsals at the country club but nothing in situ.’

The country club was the facility to the north of Tel Aviv where the special operations section was based. There were hangars of equipment, fake sets that looked like streets in different cities, flight and car simulators, not to mention the gyms, swimming pools and a prime stretch of beach for the squad to lounge about on between ops.

Yuval frowned, ‘Why not?’

‘I thought about it, Yuval,’ Rafi said. ‘But if the squad rehearses in situ the risk increases exponentially. The op area has a population density of 450 per kilometre. The Nairobi police may be corrupt but they’re not totally inept.’

Eli had another moment of chagrin. Rafi not only knew his stuff but he was ready to stand his ground with the new boss.

Rafi went on, ‘It will take twelve minutes maximum to get from contact point to swamp. It’s a decent road, unlike some in the area. The team will be in and out in two hours.’

On cue a satellite image of the road appeared on one of the screens. On another there was a ground view image. On the third, the route from the contact point and on the fourth screen some joker had projected a still of a crocodile. Jaw open; conical white teeth; teeth primed to rip apart human flesh. Eli saw Yuval’s black brows twitch into a frown.

‘Okay.’ Yuval recovered and did one of his bird-like nods. ‘Klondyke disappears into the crocodile swamp. No questions and no comeback – just the way we like it. Good work, Rafi. Next, Canada, home of the Mounties.’

Yuval moved swiftly around the room getting updates throughout the world, Far East and Australia, the US and finally, Eli’s desk, Western Europe.

Yuval checked the diving watch that dwarfed his hands and sped up his delivery, ‘So, the situation is like this. Red Cap, an asset in GCHQ for the last fifteen years, has refused to work with his third new case officer, Gidon. Eli, what’s your plan?’

Eli stood up. He didn’t bother to take possession of the remote control because he hadn’t had time to upload any images. And after all, everybody knew what GCHQ looked like. He brushed his hand across his head. ‘We have two choices. One, we bring Red Cap over here, give him a nice dinner, say thank you very much and retire him; or two, we find someone he will work with. Yes, his product is consistently good and no, we don’t have anyone else in GCHQ at his level but...’

Eli paused for effect. ‘Red Cap has never become the agent of influence we always hoped he would be. What’s more, the older he gets the less likely it is that he’ll ever get a job that involves policy-making. And that’s because he’s unpredictable. Fifteen years ago he walked into the London embassy because he was passed over for promotion. He has no Jewish connections, no friends, no family, no nothing but he wanted to do the thing that would make being passed over more tolerable for him. But, bottom line, there is a reason why Red Cap didn’t get promoted then or now. It’s the exact same reason he came to us and didn’t go to the SVR. He’s unpredictable.’

‘All agents are unpredictable. That’s part of their charm.’ Yuval said.

‘Yuval, I’m the first person to agree with you. That’s exactly what I say to the kids in training. Agents are liars, losers, fuck-ups, we all know that, but there’s a fine line between being unpredictable and being unmanageable.’

‘No agent is unmanageable, Eli. It’s just a question of finding the right handler. It’s like dating, sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. You know that as well as anyone. In truth, better than anyone. You concentrate on Red Cap. Start thinking about how to manage him because we’ve got no one else in GCHQ and no one else to help us keep tabs on 91.’

‘But we can’t control him,’ Eli said. ‘He’s an accident waiting to happen.’

‘Who says?’

Eli waved a sheet of paper in Yuval’s direction. ‘This is the experts’ report after Red Cap’s last debrief. That’s when he got drunk and smashed a glass coffee table in the safe house. The experts say he has an undiagnosed personality disorder and paranoid narcissism.’

‘The experts’ was the catch-all expression used for the psychologists, psychiatrists and assorted brain-suckers that were an integral part of the organisation. The CIA and FBI loved their polygraphs, the Brits relied on regular vetting panels, and Mossad had their shrinks; platoons, brigades, whole armies of them.

‘Experts,’ Yuval waved the piece of paper away, not deigning to read it. ‘They’ve got a name for everything. Red Cap has a drink or two and an accident. So what?’ He checked his watch, ‘Eli, we’re out of time. We’re gonna park this for the minute and you and Rafi will meet back here in thirty minutes. After I’ve spoken to the prime minister and got the Nairobi green light.’

Papers were moved and chairs shuffled back as everybody who was seated stood up to go. But Yuval wasn’t quite done. With one of his stubby fingers he stabbed at the wall screens where the crocodile had been displayed in colour-saturated glory. ‘Rafi, that was unacceptable. It is not a moment for humour and you know why: a killing must be pure.’

On the way out of the meeting Eli found himself walking beside Rafi who seemed quite undiminished by Yuval’s growl about the crocodile.

‘Can I buy you a coffee?’ Rafi said. ‘We’ve got some time before we go see Yuval.’

‘Sorry, I’ve got a few things to do,’ Eli said.

Rafi put his hand on Eli’s shoulder. The weight was uncomfortable.

‘Eli, come on,’ Rafi said. ‘Just a coffee, we’ve got some stuff to talk about before we have the meeting.’ The big man shifted from foot to foot, he was smiling. ‘I’ve got some information you might find interesting.’

‘What’s that then?’ Eli said.

‘Come and grab a coffee and I’ll tell you.’

‘Stop behaving like a kid with a secret. If you want to tell me something then do it,’ Eli said.

‘Okay.’ Rafi took his hand away. Eli looked up at him. At that moment, Eli thought just how easy it would be to hit Rafi somewhere between his hazel eyes or, as an alternative, aim for Rafi’s Adam’s apple at the precise point where a sharp punch might, if Eli were accurate, kill him.

‘Get on with it,’ Eli said.

‘We’re going to London,’ Rafi grinned. ‘That’s why Yuval wants to see the both of us. And it’s going to be big.’

‘London?’ Eli said. ‘It’s not your account, you’ve only ever worked there as a bag boy; you don’t know anything about the place, the politics, the culture. Why on earth would they want you in London?’

‘I imagine it’s because I have special skills.’

‘You?’ Eli snorted.

‘I also have a connection there who might be useful.’

5

The Office, Tel Aviv – Thirty Minutes Later

Yuval stood with his back to the blank screens in the meeting room addressing Eli and Rafi. It felt like being back in the army or on the three-year Mossad training course when you were given assignments to complete and then got graded.

‘This operation in the UK is the beginning of the most significant initiative since 1948 when the state of Israel was founded,’ Yuval said.

Eli was accustomed to a certain level of hubris when a new operation was mooted but this statement went well beyond standard introductions. Keeping his expression grave, Eli nodded and waited with considerable interest for what was to come.

‘The PM and the cabinet believe that now is the time for us to be accepted as a major power player, not just in the region, but in world politics. After all, if North Korea can be considered as such, why not Israel?’

Eli caught Rafi’s expression; he was frowning.

‘It’s not as crazy as it sounds,’ Yuval said. ‘The prime minister sees a unique opportunity and whatever we may feel about him, he’s shrewd. The situation is like this: the US is faltering under Trump; the EU is riven with dissent; Russia, for all its posturing, is falling apart economically behind the scenes. The war in Iraq is over, in Syria the war is coming to an end and when the superpowers have left the arena, there’ll be a power vacuum. We need to be ready to fill it by building our alliances not with America but with our friends in the region. To do that we need better intelligence, and that’s what we’re going to do even if we have to be a little more creative than usual and push ourselves.’

‘And the UK is where this is going to start?’ Rafi said.

‘Exactly, it’s where we begin. Instead of having to be grateful for any crumbs of product the Americans and British throw our way, the first operation in the strategy will make us appear to be pivotal to the security of the UK and thus more significant in the region. How?’

Yuval paused for effect before he answered his own question, ‘We’re going to stop a terrorist attack.’

Eli rubbed his scalp, ‘Nice idea, Yuval, but how can that be guaranteed? We don’t have the resources to infiltrate UK groups and even if we did we’d be tripping over MI5 which would make us even less popular than we already are.’

‘Very simple, Eli. The way to guarantee that we stop a terrorist attack is... by running the terrorist,’ Yuval said with simple pride.

‘I see,’ Eli frowned. The content of the morning meeting was disturbing to say the least.

In terms of his intelligence career Eli considered himself to be a simple man; a meat and two vegetables man; not an experimental gourmet who mixed incompatible foods for the novelty. Simple was good. Simple was safe. Simple worked. You made the contact; gathered operational information; developed the source; made the pitch and then you ran the source; extracting best quality product possible while keeping the source fit and healthy. Simple.

Yuval went on, ‘You two are pivotal to this operation’s success. I picked you, Rafi, because of your operational experience, and you, Eli, for your track record as the best agent runner in the organisation.’

Eli stood up and walked around the room, ‘So, the idea is that we do a false flag operation on a suicide bomber and then feed the intel to the British so they can stop it? It’s certainly original.’

Original sounded better than unlikely.

‘And the so-called terrorist has actually been recruited?’ Rafi said. ‘You’re saying Shabak infiltrated a Hamas cell at that level? Impressive.’

‘Yeah, they’re full of themselves. Another reason for us to follow through and get some glory. We can’t be seen to let the plodders in Shabak look smarter than Mossad,’ Yuval said.

Plodding sounded fine to Eli at that moment even though he’d never been tempted by the internal security service, Shabak; there was too much bureaucracy.

Yuval was still speaking, ‘We’re calling the operation Sweetbait – cute eh? What is also attractive is that we won’t need to use London’s resources which is just as well as there are going to be some changes there.’

Changes? This was news to Eli; it could only mean that Gidon was going to be fired which would leave the head of London station job vacant. Rafi seemed to have missed the allusion.

‘I have connections in London,’ Rafi said. ‘From way back but I’m sure I could reconnect. She used to work for us when I was in London; Alon was her katsa and her code name was Trainer.’

‘Ah, the legendary Alon,’ Yuval said. ‘A good man indeed, and I read about Trainer in the archives. Highly respected; skilled apparently – but it won’t be necessary.’

From across the room Eli watched Rafi nod, accepting the decision like the good soldier he was.

Eli held up his hand, ‘Yuval, I’m happy to go to London; happy to deal with Red Cap; bring him back in, clean up Gidon’s mess, but the type of operation you’re planning...’

Yuval interrupted, ‘I need a spy runner, understood? I need the spy runner.’

‘Eli, it’ll be fine,’ Rafi said. ‘We complement each other; Yuval has thought of everything.’

‘Don’t brown-nose me, Rafi,’ Yuval said. ‘Eli is the lead; you are number two. What’s more, the success or failure of this operation rests jointly on your shoulders. In other words, if one of you screws up the other one will be equally responsible. You’ll find the reading material in your mailboxes and travel will send you your documents for London.’

6

Old Street, London – A Week Later

‘I’m fromLondon Finance,’ Petra said. ‘Here to interview Andrew Canadell.’

She stood in the all-white reception area while the man behind the desk, who looked as if he’d used pumice stone to shave, wrote out a visitor’s badge and slipped it into a plastic sleeve.

‘There you are, Miss, if you just take a seat, I’ll tell them you’re here.’

It hadn’t been hard getting the interview. Not when Petra had said that London Finance was doing a series about leading CEOs. The PR department had leapt at the opportunity to give Canadell a four-page spread in the independent journal.

Five minutes later Petra was shepherded to the twentieth floor and was sitting in Canadell’s office overlooking London. The room smelt of wood polish and subdued wealth. Across the desk, Canadell sat framed by a floor-to-ceiling window with the Shard in the background.

Petra glanced down at the list of questions she’d prepared for the CEO; there was nothing too extreme on the list. Nothing that might make Canadell baulk at what she was saying or end the interview.

‘Before you took over Gomax Pharmaceuticals you worked in the drinks industry,’ Petra said. ‘How do you feel your expertise has transferred?’

Canadell leaned back in his chair, his face was florid and his shirt collar was too small. In another life Petra could have seen him in a Hogarth etching with a wig askew. In this life he tugged a yellow patterned tie over his white shirt as if the strip of fabric would conceal his gut. On the left lapel of his suit Petra saw an enamel badge and noted the design of both tie and badge in her notes. The tie was a gift from someone he liked but who didn’t know him well; it was too bright and too cheap. The badge was more complex; Petra clicked her camera pen to support her notes.

‘Good question,’ Canadell said. ‘There are certainly transferable skills and indeed, these are both people businesses. I value...’

Petra nodded, smiling with demure respect and memorised the room. She divided it into sections and noted the artefacts and objects. Later on these would be analysed to consider what they might say about Canadell and the report she produced would be sent to his business competitors. Behind him, on a small side table there was the ubiquitous family portrait, with what looked like wife number two – or perhaps even three. There was also a portrait of a school-age child on the desk. From what Petra could see, the CEO’s wife was not quintessentially Anglo-Saxon; she had dark hair and high cheekbones. Perhaps Slavic; perhaps Native American. That might prove to be interesting, but so far, in this particular interview there were slim pickings. Not much to interest Canadell’s business competitor who had commissioned the report.

To the right of Canadell, on a wood-panelled wall there was a further display of photographs. They showed Canadell posing with various politicians across the political and historical spectrum. There were also pictures of him with the most accessible royal as well as a series at various sporting events. But, Petra noted, no horse racing so possibly no gambling.

Closer, Canadell’s colossus of a desk was clear; yet mighty though the desk might be, it was functional. Tidy. Precise. Two laptops were open and as he spoke, he kept glancing in their direction.

‘And I see you’re a Londoner and support the culture of the capital in many ways,’ Petra said.

‘Yes, yes, we recently initiated a programme to take young people to opera rehearsals. Although we may have missed it for this season.’

‘Why’s that?’ Petra said, smiling with great understanding.

‘Timing,’ he shifted in his seat, as if he was trying to get comfortable on the deep padded leather.

That was interesting. What was it about the question that made Canadell display an anxiety tell? Was it personal or professional?

‘Of course,’ Petra said. ‘These programmes have to be organised so far in advance. But you must be keen to continue, having done so much good with these initiatives.’

Canadell nodded, ‘We have. So many young people helped. So many young lives enhanced by the power of music. It makes me very proud.’

‘I can see that. Who is involved? Would I be able to speak to someone from the charity and get a quote? I think it’s something that people would find fascinating.’

In answer, Canadell pushed the desk so that his chair shifted back, ‘Of course,’ he said. Of course not, he meant.

Yes, there were inconsistencies about Canadell. He looked like a rugby player gone to seed. At a guess, Canadell was using the opera charity for either personal reasons or financial; in other words, the usual: sex or money. Meanwhile, her part was coming to an end.

Petra uncrossed her legs, leaned forward and switched off the Zoom audio recorder. ‘Thank you for your time,’ she said. ‘I’m very grateful. I’ll send the copy to your PR department and will wait for your approval.’

Canadell nodded, but he wasn’t listening; he was looking at his laptop and frowning.

Petra stood up and walked around the desk to shake hands with Canadell. She was able to see the screen; it was a live update of the Hang Seng. ‘It’s been great to meet you,’ she said.

Glancing at her watch, she made a note of the time to feed into her report. The geeks back at the office might be able to work out what was disturbing Canadell. There couldn’t be that many options on the Hang Seng screen at that particular time. And her role was over; she’d write up both the article and the private report. The article would contain the superficial information about Canadell; the do-gooding CEO that would appear in London Finance. And her report, the one commissioned by Canadell’s business competitor that contained detailed thoughts and recommendations for further action, would go to her employers, the security company.

7

Palestinian Territories – Two Weeks Later

Today I was moved to an amazing room, the walls are purple and painted with verses from the Koran and green birds. It’s so beautiful. The birds are painted in shades of turquoise, lapis lazuli and emerald. They represent the flock that carries the souls of martyrs to Allah and soon, inshallah, they will bear my soul to Jannah.

I stroke the wings of a bird and feel paint and plaster under my fingertips. I’d be lying if I said that I’m not thinking about what I’m leaving behind. Sometimes I ache in my stomach when I hear the children laughing as they knock around a ball in the dusty courtyard outside. But in Jannah the children won’t have been displaced; they won’t know poverty and disease, they won’t have been bombed and cut down and injured and mutilated. They won’t be like the broken babies I nursed at the hospital, day after day after day.

Would it be different if I had my own children? Of course it would. For one thing, if I were a mother the Martyrs Committee wouldn’t have accepted me. Neither would I have been chosen if I were the sole support for my own mother who will, when the time comes, receive a good pension and be honoured.

Knowing what I’m doing for my mother makes me so happy. At last she’ll have a reason to be proud of me – her divorced and barren daughter. At last she’ll be able to talk of me with pride because I’ll be the one keeping her secure and in comfort for all of her days.

For a moment I remember how we used to have picnics on the beach in Gaza. In summer we stayed indoors during the day hiding from the heat. But when it got dark and a few degrees cooler we’d come outside and bundle into my uncle’s rickety pick-up truck, the car with the blue number plates that identified us. Once we got to the beach we’d settle ourselves on sand still warm from the day and eat the kibbe, tehina and tabbouleh that my mother and her sisters had made. Sometimes I’d sit with my feet in the cool sea eating watermelon, seeing just how far I could spit the seeds into the darkness. And then we’d sing the whole way home as the truck rattled and rumbled through the night.

I always tried to sit near the back of the pick-up so I could feel the night air cool my arms. Usually I’d have the sleeping weight of one of the little ones on my knee. If I was lucky it would be Amira, holding her tight, holding her safe, holding her close to my heart. If I was less lucky it would be my little brother Wasim who was like a puppy, always looking around, squirming to get out of my arms and lean out of the back of the open pick-up.

‘Kun Hadhira,’ my mother’s voice would be shrill with fear from the depths of the truck. ‘Be careful.’ A lot easier said than done with a metre of slithering, squirming, laughing little boy on your lap who wanted to see and be, and howl at the moon with the sheer joy of life.

I swallow hard thinking of that time. That good time in the past.

Outside the window I can hear the sound of the wind, like the distant roar of the sea and then a clatter of a metal pot that hasn’t been secured. It must be rolling around outside. The window is spattered with shapes like little sandy clouds and the sky beyond is yellow, murky, dark. Sadly, it’s not simply the sand and the heat that’s the problem in Khamsim weather, it’s the pollution. Poor Mawmia – her asthma will be torturing her. I can see her fingering and clutching her inhaler in her gnarled arthritic hands, frightened to put it down, frightened not to have it close by, frightened that she will suffocate. I always made sure there was a spare inhaler in the kitchen dresser drawer – I hope she remembers – or that someone else does.

The door opens and Abu Muhunnad stands framed, as if in a picture, ready to come in.

It must be time.

‘Salaam alechem. May we enter?’

‘Marhaba. Al’afw.’

Behind Abu Muhunnad there’s another man. I haven’t seen him before. He’s younger and paler and harder-faced beneath his beard and behind his glasses.

Abu Muhunnad moves towards the single chair and the new man stands slightly behind him. I feel like he’s examining me and feel uncomfortable.

But Abu Muhunnad’s voice is warm and soothing, ‘We have something important to discuss with you.’

Of course I’m nervous but I also feel a surge of exultation and relief. At last the waiting is over. I sit on the edge of the bed upright, feet together, trying to breathe slowly.

‘I am blessed,’ I manage to say. ‘And honoured to have been chosen.’

Abu Muhunnad’s hands are folded across his black clad belly. ‘My child, we’re here to tell you that you’re not going on the mission that we have been training you to accomplish.’

What is this? For a few seconds I wonder if I have heard wrongly, misunderstood what Abu Muhunnad is saying. Not going? That can’t be right.

I massage my forehead as if the action will help me to absorb the information. Perhaps this is some final test to see if I’ve got the faith to complete my mission or whether at the last moment I will fail. I must convince Abu Muhunnad and the other man.

‘I’m ready Abu. I’ve memorised the map of the target. I know the bus stops on the corner of Dizengoff and Ester Halmalka. I know the café is two hundred metres away on the right-hand side. I know there are two orange trees in front of it. I’ve got a copy of American Vogue to carry to show I’m interested in fashion. And I know I must sit exactly in the middle of the café to make the maximum impact.’

‘We know; we know you’re well prepared; indeed, you’re perfectly prepared. We could ask for no more in your dedication, but you’re not going to the café.’

‘Why?’

‘Because it’s our decision,’ the other man says.

I smooth the bed cover with my hand and find a small thread that I tug between my nails.

‘Am I not pious enough?’ I say.

I’m still uncertain whether this is a test and I have to prove my commitment and obedience. Maybe I’ve failed and all along there’s been someone else training, someone ready to go for the same target who is more righteous. That must be it. Looking at Abu Muhunnad’s face and then the cold expression on the face of the stranger I know that’s the truth. Someone else had been chosen.

I press my lips together to stop myself crying. There’s nothing I can do, I’ll be returning to my mother where I will help her wash and dress and be the comfort of her old age. My sister will visit with my nieces and nephews and I’ll continue to be the failure.

‘I understand,’ I say. ‘It is the will of Allah.’

I raise my eyes and catch a glance between the man and Abu Muhunnad.

‘Habibti.’ Abu Muhunnad leans forward and places both hands on his knees. ‘It’s because you’re both pious and brave that you will not complete this mission. You see, there’s something else for you to do that’s far more important and more dangerous; something that only a special daughter can do for the glory of Allah and the destruction of his enemies. You are going to London.’

That night I don’t sleep. I lie on the bed listening to the wind and thinking about what Abu Muhunnad said. I am going to London. Can it be true?

Abu Muhunnad gave me a phone with a European number. He said it was safe and wouldn’t be scanned by the Jews. I was going to use it so that I could call my mother when it was too late to change anything; call her to hear her voice for the last time. If I’m going to London, will I still be able to call her? Maybe the commander will take the phone. What shall I do? In the dark of the room I look at my phone – I’m sure Allah would forgive me if I call my brother Wasim and tell him that I am doing God’s work and that he has to make sure that my mother has a supply of asthma drugs. And to say goodbye.

I text a message to him.

I am going away. Look after Mawmia. See she has spare inhalers.

Now I can sleep. I close my eyes and begin to drift off. On the bedside table the phone vibrates. I answer it.

‘Where are you?’ Wasim says. ‘What are you talking about going away? Who said you could?’

Always the same, my brother, just like he was when he was a kid, asking questions, demanding answers.

‘I can’t tell you more but you must promise to look after Mawmia.’

‘What, are you going on vacation with our sisters?’

‘No,’ I say. ‘Wasim, it’s secret. I’m not coming back.’

I’m now sorry I texted him. Even more so when he says, ‘What do you mean, you’re not coming back? Sister, I may be your younger brother but I am still the head of the family, I’m your guardian.’

‘I’m going to be shaheeda,’ I say.

There is silence at the other end of the phone. I hear his breath close to the microphone.

‘What? What did you just say? Are you crazy?’ Wasim says.

‘I shouldn’t have told you. I’m sorry, forget it.’

‘It’s too late now, how did you... who’s guiding you, Sahar?’

‘Abu Muhunnad,’

‘Never heard of him. What’s his full name and family? Where does he come from?’

‘Brother, you haven’t been here for a year; things change and people change. You don’t know everybody anymore and what’s more, you don’t know what it’s like living here.’

‘That’s not the point. I’m your guardian, I’m responsible for you, Sahar; I’m responsible for the family. Nobody told me.’

‘I’m fine and I’m being looked after. I can’t say any more than that.’

‘I’m going to find out what’s going on. I’ll call you again. Soon.’

8

Swiss Cottage, London – The Same Day

It was good being back in London and interesting too. Eli sat opposite Gidon in the Singaporean restaurant; ostensibly he was there to get an update on Red Cap but Eli had an additional agenda; he wanted to find out just how close Gidon was to being sent home.

‘I’ve had such a lousy run of luck,’ Gidon paused with a spoonful of hot soup halfway to his mouth. He sounded more like a washed-up gambler bewailing his lack of success on the slot machines than a station manager with two decades of intelligence experience.

‘First the passports get left in a phone box by the idiot bag boy and then your man Red Cap goes mad – both in the same month. God knows, I could have handled one crisis; but two, so close to each other? Can’t be done. And what’s killing me, is that neither of those incidents were my fault.’ Gidon swallowed the soup and coughed over the chilli.

As ever, Eli contained his thoughts: he didn’t say that if Gidon had run a tighter ship, better procedures would have been in place and passports might not have been left in a Sainsbury’s carrier bag in a phone box. Neither did he say that Gidon had completely mishandled a valued asset whose most recent intelligence had given them the tools to target Klondyke. Without Red Cap’s product, Klondyke would have been helicoptering to his golf club instead of transiting a crocodile’s digestive track. But explaining all of this to Gidon was pointless. What would it achieve? Nothing. Eli would just be grinding yesterday’s man’s face down in the dirt.

‘How’s your laksa?’ Eli said.

‘Good. Delicious in fact. I didn’t know about this place and I’ve lived here for three years.’.

There was silence at the table. Gidon broke it, ‘So, what are you working on? You seem to be here mob-handed.’

‘You know I can’t say,’ Eli smiled at the freckled face and creased forehead across the table.

‘Come on. I know I’m last year’s flavour, but I’m still head of London station – at least I am for the moment.’

‘Gidon, drop it.’

‘What’s the new guy like?’ Gidon said, still anxious to be ‘in’ with the news.

‘Different.’

Gidon attempted to pour more wine into Eli’s still full glass and then refilled his own. ‘D’you remember those morning meetings we used to have with Avigdor? The discussions and debates? Now, that man was a leader; a philosopher, a man of intellect and culture.’

‘Like I said, Yuval is different,’ Eli said.

In terms of discovering what had driven Red Cap to trash the safe house, the evening was a washout. All Gidon did was reprise the contents of the contact report. However, by the time Eli returned to the serviced apartment it was clear that Gidon was more than halfway out of the door and the job of head of London station would be vacant soon.

––––––––

The next morning Eli was able to observe just how different Yuval’s leadership style was to Avigdor’s. They were sitting in the safe room at the embassy in Palace Gardens crowding round one end of the big table since it was only the three of them: Yuval, Rafi and Eli. A folder with a printout lay on the table but it was being shunned as if it contained a virus. They had already received the report in their overnight mailbox and it didn’t make happy reading; it was a transcript of Sweetbait’s conversation with her brother.

‘So, the situation is like this,’ Yuval said. ‘We have a problem; we need a solution. Ideas please.’

Eli laid down the croissant he was eating on the paper plate, ‘We can’t move until we’ve got a lot more information about Sweetbait’s brother. If he’s well connected he might make waves.’

‘So what?’ Yuval said. ‘So, he thinks it’s not Hamas but some other group. Or maybe it is Hamas but for once they’ve got an operation that’s so water-tight no one knows about it. I don’t think we should fixate.’ Yuval said.

‘I agree,’ Rafi said. He picked up the plastic glass that contained an inch of a kale and kiwi fruit smoothie. He tossed the drink to the back of his throat and then threw the empty container in the direction of the bin in the corner. The glass plopped in but some drops of green liquid spattered the cream plaster.

‘It’ll be a total mess if he turns up in the UK,’ Eli said trying not to sound as negative as he felt, trying to find a solution to the problem. ‘But he won’t be able to find her if we take away her phone.’

‘That won’t work. We take her phone, she uses a phone box,’ Yuval said working his lips with concentration. ‘We change the sim card and block international calls but we still have the same problem.’

‘Okay, if we’re going to do this we need someone in the school,’ Eli said. ‘We need someone in the school to be her friend and mentor, who’s there round the clock. Someone who, if push comes to shove, can get Sweetbait away from the brother if he turns up.’

‘Good, I like that. Rafi see who might make a good student. Maybe one of our youngsters – a boy. No, better a girl. That’s what the experts say.’

Rafi opened the laptop in front of him and with his big hands started to access the organisation’s database. The tap-tap of his fingers filled the room.

‘I thought you didn’t believe in the experts’ reports,’ Eli said.