Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Polygon

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Alice Rice Mystery

- Sprache: Englisch

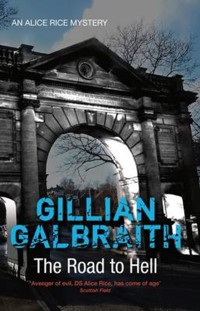

When the body of a half-clothed woman is discovered in an Edinburgh park, a murder investigation is launched. The victim has not been reported missing and there are few clues to her identity. Soon after, the naked corpse of a prominent clergyman is found, also in a park. DS Alice Rice wonders if the same killer is at work, and if so, what is the connection between the apparently motiveless attacks? The Road to Hell, the fifth in the series, takes the policewoman to new personal depths and along a trail that leads to some of Edinburgh's darkest and scariest corners. Praise for the Alice Rice Mystery series: 'The new Rebus' - Sunday Express 'Chilling realism' - Edinburgh Evening News 'Red herrings, lies and cul-de-sacs interlink to create an enjoyable read and an awkward puzzle to solve' - The Dorothy L. Sayers Society 'Vivid and exciting . . . not a dull page from start to finish' - Alexander McCall Smith 'From its bloodstained opening . . . a compelling read. Gritty and charming in turn' - Scottish Field

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 407

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE ROAD TO HELL

First published in 2012 by Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd West Newington House 10 Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QS

www.polygonbooks.co.uk

Copyright © Gillian Galbraith 2012

ISBN 978 1 84697 225 6 eBook ISBN 978 0 85790 176 7

The moral right of Gillian Galbraith to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Maureen Allison

Colin Browning

Douglas Edington

Lesmoir Edington

Robert Galbraith

Daisy Galbraith

Diana Griffiths

Christine Johnson (Bethany Christian Trust)

Jinty Kerr

Alan Montgomery

Roger Orr

Aidan O’Neill

Dr David Sadler

DEDICATION

To Hamish, with all my love

Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

1

The middle-aged woman in the poorly-fitting yellow anorak was twisting the ring on her finger, first one way and then the other, all the while trying to slide it over the enlarged, inflamed middle joint. She appeared not to notice the queue of people growing behind her. Now bowing her head and starting to lick her finger with her tongue in an attempt to ease it, she muttered to the assistant, ‘Got any soap, dear?’

The embarrassed girl, dressed all in black, shook her head, then peered up from beneath her straw-coloured, floppy fringe, eyeing the line of increasingly restive customers with concern. Looking at them, she shifted her weight from one foot to the other, rocking nervously from side to side. After a further minute had passed without any progress, she asked, pleadingly, ‘Maybe we could get on with things, while you’re getting the ring off? Have you got the paperwork with you? Your passport, your driving licence?’

‘Eh?’ the woman snapped irritably, concentration broken on her all-engrossing task. A bubble of spit glistened on her lower lip.

‘Your passport? Your driving licence?’ the assistant repeated, tapping her finger on a yellowing, typed notice that was pinned to the wall detailing what was required of sellers. ‘Like what it says here.’

‘I’ve no passport, I’ve no need of one. And I don’t drive either.’

‘A household bill, maybe . . . electric, gas, something like that? That would do instead. Everybody has them.’

‘Not this body, dear. I’ve not got any of them with me. But it’s gold all right, if that’s what’s worrying you. It’s my wedding band.’ Then, giving herself a rest from the strenuous removal attempt and sounding wheezy and out of breath, she added, ‘It had bloody better be anyway. Archie gave it me. You can bite it or whatever you do, check it with your teeth like the gypsies. But you’ll need to wait until I’ve got it off my finger.’ She removed her chewing gum and smiled winningly at the girl as if to charm her into submission.

‘I’m sorry but we can’t take it,’ the assistant replied, shaking her head, ‘not without the proper documentation.’

‘Bingo!’ said the woman, beaming even more broadly, holding the ring triumphantly between the still sticky thumb and forefinger of her right hand, and thrusting it at the assistant.

The girl shook her head again, mulishly, and as she did so, the lank curtain of her hair swung from side to side across her eyes. ‘No documents, no sale. That’s the rule in all Money Maker stores.’

The middle-aged woman, now chewing her gum again, appeared unabashed by her refusal and continued polishing the ring on the sleeve of her yellow anorak. In fact, seeing the girl’s implacable expression and determined to get her way, she decided it would be wise to change tack. If charm was not to going to win the day then coercion would have to be used.

‘Listen, dear,’ she said, moving forwards and brandishing the ring in the girl’s face, ‘you’ve a big sign outside saying “All gold wanted – good prices paid”. Is my gold not good enough for you, then?’ Both of her fists were now parked on her well-padded hips and her feet were set wide apart, like a boxer readying himself for a fight. After wrestling with the ring for the last five minutes she had no intention of giving up now. Immoveable, she looked round at the queue of people behind her, suppressing a smirk as she recognised them for what they were, her unwilling allies. Few could resist the silent pressure that they were unwittingly exerting, certainly not this stick-thin teenager. A puff of wind and she would drift skywards.

‘I’d like the money today, dear, and this is gold. Right? Got that? Your sign outside says nothing about paperwork. Gold is gold, OK?’

The girl pressed a button on her counter to summon assistance but no ringing sound came from it. She tried again, pressing harder but only eliciting a faint clicking noise for her pains.

‘Shit!’ she murmured to herself, looking down at the button and hitting it crossly one final time. In doing so she hurt her knuckles, and started rubbing them against her shoulder.

‘Your alarm button not working then? Now, my gold?’ the woman said quietly, between chews. ‘There are lots of people waiting, dear. They’ll be getting awfully impatient, you know, some of them may just walk out . . .’

‘Eric! Eric!’ implored the flustered girl, waving to attract a male assistant’s attention. ‘I’m needing some help over here.’

At her words, the youth put down his orange duster and moved away from the bank of widescreen plasma TVs that he had been standing beside and watching. He, too, wore only black clothing. He was heavily built and walked with the muscle-bound, wide-legged gait of a professional bruiser. All the TV screens around him showed the same picture. A blonde woman in a leotard sat on an exercise bicycle, pedalling effortlessly while smiling inanely at the camera. Any accompanying sales spiel was lost as the sound was turned off.

‘I’ll attend to you, flower,’ he said coming up to the woman and cupping her elbow with his meaty hand, attempting to waltz her slowly towards another empty counter.

‘Get your mitts off me, son, or you’ll hear my alarm button go off all right, just you wait and see. I’ll shout the place down.’ She disentangled herself from his grasp.

‘OK, OK. But if you’ll not move we’ll have to get help – police help,’ he said in a hushed tone, looking into her face, taking his mobile from his pocket and crooking an index finger above the keypad. Realising she had been outmanoeuvred, she turned her back on him and strutted out of the queue, keeping her chin held high in an attempt to preserve the shreds of her dignity. There were other places, after all, plenty of them less finicky with their paperwork than this one, less choosy when gold was on offer. Grasping the handle of one of the double glass doors, she toyed momentarily with the idea, the luxury, of threatening them with the trading standards people. But it would be an empty threat and only annoy them further, which would be pointless.

Three hours later, in the same Money Maker store, DS Alice Rice looked up at the CCTV camera pointing directly at her and took her place at the head of the queue. The reflection staring back at her in the lens was as distorted as that on the back of a spoon, splaying out her nose and making her eyes appear small and piglike. She looked more like fifty than forty, she thought, and her dark hair appeared to be framing an entirely unfamiliar face.

‘I’ve come for the notebook laptop,’ she said to the lank-haired girl.

‘We’ve a few of them in here at the moment. We’ve got an Apple, a Sony and a Toshiba, too, I think. But you’ll need to go to that counter, over there, if you’re buying.’ She pointed to the far end of the shop. Stacked by the counter were turntables, battered cardboard boxes overflowing with DVDs and an army of upright Dyson vacuum cleaners.

Crossing the floor and stepping over the open boxes, Alice Rice addressed another black-clothed clone. ‘The notebook laptop, please. Donny was going to phone you about it earlier, he said. I’ve come to collect it.’

‘You from SART, then?’ the man asked. ‘Donny told us you’d be here by eleven. Eleven on the dot.’ He sounded annoyed. Glancing at his watch to emphasise that the time had long since passed, he bent down and removed a smallish box from below his counter. Still frowning, and consulting the watch again to further underline his point, he handed the package over to the plain-clothed policewoman.

She wondered why he was so bothered about the time. He was not exactly run off his feet, she was his only customer. What possible difference could that half hour have made to him? The jerk. All the same, she was relieved that he had known exactly what she was supposed to be collecting. No one in the SART office had told her the make of the notebook they were after.

Once it was safely stored in her carrier bag, she decided to waste a few more minutes having a look around the store. Time had to be killed this morning and here was as good a place as any to do it in. The shop was warm, and browsing its contents might distract her, repel the repetitive thoughts which were constantly trying to invade her brain. It might, briefly, obliterate her obsession with her two o’clock appointment, her forthcoming tribunal hearing. Her very own, and imminent, personal disciplinary case.

As she wandered about the shop, she was struck by its resemblance to a wholesale outlet, but it seemed a strange, sinister variant of the species. Goods were piled high on all the available floor space, the walls were hung with them and not an inch of unused shelving was visible. But despite the bright strip-lighting, crisp decoration and the superabundance of merchandise, the place reeked of poverty and desperation. The assistants drifting about reminded her of undertakers in their black clothes, circulating within a Chapel of Rest. They spoke to everyone in hushed tones and their customers replied in the same way, as if they were embarrassed to find themselves in such a place. The body-language of the patrons conveyed one message and one message alone, that they were ‘just looking’. They were not here to buy, and certainly not to sell.

In the absence of any apparent trade, it seemed a miracle the business survived at all, she thought. But a notice on the wall boasted that branches of the chain were to open from the Forth to the Clyde. Money Maker appeared to be flourishing in the ailing towns of the Central Belt like some kind of fungus living off a dying tree. According to the advertisement, its spores were soon to take root in the cold, grey streets of Kirkcaldy and on a disused lot by the dog-racing track in Thornton.

‘Are you after anything special?’ an assistant, who had glided silently to her side, asked her in a sibilant undertone.

‘Just looking, thanks,’ she caught herself whispering in return. After he had moved away, she turned her attention to the rear of the shop. High up on a wall hung a selection of crossed fishing rods and nets, and stacked immediately below them were a row of golf bags, shiny clubs protruding from each of them. On shelving to one side was a display of power tools, some in mint condition, but others mud-spattered and worn, as if plucked, still buzzing, from their building sites only minutes earlier. Nothing tempted her.

A customer coming in through the swing doors set a couple of tiny handwritten tickets on a nearby alarm clock fluttering in the artificial breeze, like the wings of a frantic insect. Catching sight in the distance of a silver-plated saxophone displayed against the blue silk lining of its case, Alice wandered over towards it, attracted by the beauty of its sinuous shape. Gazing at it, she felt an overwhelming urge to possess it. Maybe Ian would like to draw it, or even learn to play it? Of course, other lips, strangers’ lips, would have blown into it, dribbled into it, and that might well put him off. Besides, the price of ninety-five pounds seemed steep, and money might be tight if the worst happened this afternoon. He might think she had chosen it with herself in mind, despite it being ostensibly a present for him? He would be right, and he could, and would, see right through her. But, with its fine filigree engravings it was a wondrous object. The sort of thing that would be appreciated by anybody, surely?

While she was still mulling things over, trying to talk herself out of buying it, a man joined her, also intent upon inspecting the musical instruments section. He smelt strongly of stale curry, and in his left hand he held a stick, on which he leant heavily. Hobbling past her, he came to a halt before a stand on which seven electric guitars were propped up. Humming to himself, he began slyly inspecting the instruments and their price tickets. As he bent over to examine one, he lost his balance and toppled into a large pile of treadmills and dumbbells stationed at the base of the stand.

‘Feck!’ he shouted, lying spreadeagled on the floor. Instantly, a pair of assistants appeared from nowhere. Yanking him up, one of them hissed at him, ‘Forget it, Paddy. You’re not getting it back unless we get the cash.’

The other stood in front of the guitars, his arms crossed, deliberately blocking the man’s view with his body.

‘I just need it the one night, boys,’ the man pleaded. ‘I’ve a gig booked in Ratho. I could give you the money after it’s over and I’m paid.’

Alice decided that she had seen enough. Ian would not thank her for the saxophone. Like the rest of the items in the place, it would carry with it its story of shattered dreams, hobbies abandoned, jobs lost, mortgage payments now in the red. Almost every article was a tangible reminder of human misery or folly, including the saxophone, and that thought would certainly put him off. Her, too, thinking about it dispassionately.

And, of course, a fair few of the things there told a different story, as the SART boys knew only too well: one of housebreaking and heroin. Camouflaged among the once-treasured possessions were a mass of stolen goods.

Having had her fill of the place she walked towards the door. Next to the entrance were a couple of locked cabinets, both filled with an assortment of highly-polished jewellery, calculators and mobile phones. For a second, sunlight glinted off a golden bangle, the reflection temporarily blinding her. Another reflection danced on the pavement below, a third flitted about on a leather jacket worn by a passer-by. The cabinets, she noticed, had been angled artfully by the management, arranged to attract those outside the shop into it, acting as lures to draw them in like fish into a trap.

‘Sure there’s nothing I can help you with?’ It was the same lisping male assistant as before. He smiled at her, as if to persuade her to come back inside. Behind him she could see Paddy being frogmarched to the exit, his stick waving uselessly in the air like the leg of an upended insect.

‘No thanks . . . I’ve just been looking,’ she said.

On Leith Walk, Alice headed southwards, trying to look into each of the dusty, old-fashioned shop fronts as she dawdled past them. She knew that if she allowed her mind to drift, she would find herself rehearsing her evidence again, answering questions which might never be posed, justifying herself to herself like a mad woman. How the hell had she got herself into a situation like this?

Suppressing her inner dialogue, she stared into the shop windows. To her eyes, they seemed anachronistic, a collection of fossils from an older, slower world of commerce, an age untouched by computer technology and internet shopping. There was an old-fashioned barber’s shop complete with striped pole, a tattoo parlour with its proprietor’s name dripping in blood-red letters, and cheek by jowl with it, a secondhand bookshop. Leith’s glory days were long since over. A few of its street names, Baltic Street and Madeira Place, hinted at its romantic past as a maritime port. Recently, city money had been pumped in to redevelop, renovate and restore the place, but despite the millions spent on it, its couthy character had never quite been extinguished. It was like an old Scots lady, her tartans now replaced by stylish silk clothes, but who betrayed her origins every time she opened her mouth.

Next to the bookshop was an office, deserted, with a Polish name emblazoned above the door and fly-posters pasted across its cobwebbed windows. Its abandoned state was easily enough explained, she thought. Nowadays, there were precious few Poles left in the capital to use its services, the cold wind of recession having blown most of them back to Warsaw, Cracow, Gdansk or wherever.

Maybe, after the hearing, she too would find herself jobless, she mused. Conscious that she was sinking into the quagmire of doubt again, she wrenched her attention back and began staring through the glass of a shoe repairer and locksmith’s door. Deliberately, she focused on the display of mortise locks and Yale keys inside as if they were of interest, exhibits worthy of study. Moving onwards she forced herself, once more, to put her appointment out of her mind, to stop herself dwelling on her imminent professional nemesis. But with the hour growing closer it was becoming impossible.

In a final attempt, she halted to look in the window of the One-Stop Aquarium Shop, her eye momentarily caught by an iridescent fish darting about its tank, its tiny body glinting like a jewel in the clear water. But as she was watching it, unconsciously she started to finger the folded-up piece of paper in her pocket, feeling the edges of the Misconduct Form between her thumb and forefinger. It was dog-eared and discoloured from too much handling, and on it were recorded the two charges laid against her.

She knew the wording by heart. The first was for revealing ‘in a manner that was not for police purposes’ that Robert Longman was a sex offender. The second was for ‘stating to a named Professional Standards Department Officer in the course of his inquiries that she had not been the source of such information when she did know this to be false and for thereby carelessly or wilfully creating a falsehood’. In short, charge number one was for disclosing unnecessarily that Longman was a paedophile, and number two was for lying about having disclosed that information.

At the hearing this afternoon, she must keep her nerve, she told herself. Tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. And if they did not believe her, then . . . then, then? Then so be it. But they would, because it was the truth. So they bloody must.

But envisaging the tribunal, she could feel the panic rising within her. How many times had she seen juries acquit those she knew to be guilty? In one case a complete confession taken by her had been withheld from a jury for procedural reasons. But it had convinced her, and she could still see the accused punching the air as the verdict was delivered. In another case, the newly-liberated man had been unable to resist gloating, goading them all as he left the courtroom by giving them chapter and verse of the offence, providing new and revolting details that only the guilty person could know. But miscarriages of justice went both ways, and the innocent were sometimes locked up.

How had she got into this mess? The answer was simple. All thanks to that bastard, Stevenson. But for his inability to control himself, and tell the truth, she would not now be teetering on the edge of dismissal.

Just a few more hours to kill, helping the boys in Gayfield, and then on to Fettes HQ, where all the formality and gravitas of the law would be on display to impress or intimidate her. As if the very word ‘hearing’ in itself was not enough to make a cold shiver run down her spine.

A double-decker bus hooted its horn at a passing cyclist, the man’s helmeted head low down on his handlebars, and the noise brought her back to the present in the nick of time. A second later, in her preoccupied state, and she would have collided with a post from which was suspended one of the many ‘I Love Leith’ banners that had been hoisted the length of the Walk. Well, I don’t, she declared cantankerously, surveying its litter-strewn pavements and stepping out of the way of an abandoned armchair. Who does? They protest too much. The feel-good slogan trumpets the burgh’s unloved and miserable status, like a valentine some sad person sends to himself.

SART – the Search and Recovery Team – were based at Gayfield Square Police Station. The squat, toad-like shape of the sixties building with its warty, grey-harled surface, gave fair notice to all and sundry of the nature of the accommodation to be found within. There were suites of drab, functional rooms without ornament of any kind, all painted in tired shades of magnolia. Posters on the walls warned of the dangers posed by adulterated heroin and the use of dirty needles. Telephone numbers to ring in case of domestic abuse, child abuse or substance abuse were on display, and everything had been translated into at least four languages, English alone long since having become insufficient for the city’s needs.

The office to which she had been seconded for the day was tucked away at the end of a narrow corridor on the second floor, and was as unobtrusive and low-key as its occupants. In order to get into it, Alice had to push with her shoulder against the door, dislodging as she did so a recently-recovered stolen bicycle which had been propped up against it. Donny McDaid, a plain-clothes constable and one of the stalwarts of the operation, had his sturdy, denim-clad legs up on his desk. A tattooed arm rested on the top of his computer. With his left hand he was busy fidgeting with the rubber band that held his ponytail in place.

‘Any luck with the notebook?’ he inquired genially as she entered.

‘Yes.’

‘Good on you.’

‘Aye. Well done,’ Fergus Walsh, another team member, chipped in. His eyes were roving over a white board on which the names and telephone numbers of all the pawnbrokers in the capital had been scrawled in black magic-marker. With a sleeve of his cotton jersey he rubbed out one entry and inserted another in its place.

‘It wasn’t that difficult,’ Alice said defensively, handing over the laptop to Donny.

‘Not for a quick learner like you, eh?’ Fergus retorted, winking at Donny and returning to his desk.

‘Tea?’ Alice asked, turning towards the white plastic kettle and stained cups on the metal filing cabinet. Peering inside the kettle, she noticed that the furred-up element appeared to have burnt itself out and melted the plastic. She fished a couple of old teabags out of it.

‘You’re still on trial, mind,’ Fergus said, then, regretting his crass choice of words, added quickly, ‘. . . as a tea maker, I mean.’

‘But you’ll be making it, eh – because you’re a woman,’ Donny added, seeing his colleague’s embarrassment and trying to repair the damage.

‘I’ll be making it because I haven’t a clue what to do in this place.’

‘Like I said,’ Donny retorted, still stroking the back of his head, ‘because you’re a woman.’

Sipping from the chipped mug, Alice stared at the screen in front of her. On it was a seemingly endless list of names and transactions carried out at Cash 4 U branches the previous day. As she scrolled down it the words began to merge into each other until her eyes glazed over in boredom, lost in a sea of now meaningless typescript.

‘How do you do it? How can you tell what’s dodgy and what’s not, simply from that?’ she asked Donny.

‘Well,’ he replied, ‘see that entry? Number 313?’

‘Yes. The Blackberry. Sorry, Blackberry Bold 9.’

‘Never mind the type for now. Look at the name opposite it. It says Catherine Simpson, right?’

‘Yes.’

‘Well, she’s no business having a phone like that. Know why?’

‘No.’

‘Easy,’ Fergus butted in. ‘She’s at an address in Craigmillar. Blackberries don’t grow in Craigmillar, now do they? And she’s Kevin Thomson’s girlfriend. That’s what he does, see? He takes the stuff from someone else’s house over in the New Town or wherever, then he uses his girlfriend, his mum, his cousin, someone he thinks we don’t know about, to sell the stuff in the pawns for him.’

‘So this isn’t the first time he’s used her, then? Doesn’t he ever learn?’

‘Nope,’ said Donny smugly, ‘none of them do. We get their photos from the CCTV, sometimes their prints or DNA from the stuff and still they come back for more. They’re half-witted junkies, most of them.’

‘See, in this op we’re like ghosts. We don’t exist. They see us,’ Fergus explained, ‘in the pawns with them. We’re checking up, but they think we’re selling something like they are. They think we’re just another punter. And out on the streets we’ve been taken for all sorts. A couple of days ago it was as a Big Issue seller, seriously.’

‘Speak for yourself,’ Donny retorted, stirring another spoonful of white sugar into his tea, then adding, ‘and that was the day you were wearing your best clothes, too.’

Glancing up at the clock on the wall, Alice said, ‘I’ve got to go. Time for my trial.’

‘Break a leg,’ Donny said wanly, holding up his hands for her to see, the index and middle fingers crossed on both of them.

2

The sight of the Fettes HQ building made Alice feel queasy. Its spare design was silhouetted against the leaden sky, and its bulk cast her into the shade, temporarily blotting out the insipid winter sun. Passing through the glass double doors, she noticed on the right-hand wall a mass of brightly-coloured, child-friendly pictures each bearing its own caption. All of them depicted a simple, straightforward world in which policemen in their smart uniforms were doing good, busily apprehending law-breakers and making the world a safer, better place. If only life was so simple, she thought ruefully.

‘You’re here for the hearing?’ the burly man on the reception desk asked her as she approached. She nodded, her mouth dry and all inclination to speak having vanished.

‘Rice or Stevenson?’

‘Rice,’ she replied faintly, noticing a former colleague and giving him a wave. But he did not return it, passing quickly by as if any longer in her presence might contaminate him.

‘You DS Rice, then?’ the receptionist demanded with unconcealed curiosity, viewing her, she thought, with the sort of interest he might once have shown in a condemned man.

‘Yes. How d’you know?’

‘By the colour of your face, love. You’re as pale as a sheet. You’re the options-in, eh?’ She nodded again, wishing the expression still remained a mystery to her. Until six months earlier it would have been meaningless, but no longer. ‘Options-in’ or ‘options-out’ described the two possible types of disciplinary hearings. The first, reserved for trying more serious offences, allowed the panel to return any of six possible verdicts: a warning, a fine, an increment fine, reduction in rank, a requirement to resign or dismissal. Only the first three verdicts could be returned in the ‘options-out’ hearing and no lawyers were involved in them. They were kept in the family, as purely internal police matters. Now, she thought with regret, she could answer an exam question on disciplinary hearings and the procedures associated with them. Give a lecture on the subject if the need arose.

As she entered the Force Conference Room she had no idea what to expect. She had never before been admitted to this holy of holies. Striding through the doorway, trying to look as confident as an innocent person would, she immediately recognised Alec Norton, the lawyer appointed by the Police Federation to represent her. He was a lanky, unsmiling man with an excessively reserved manner, and at their first meeting she had not taken to him. On that occasion he had made her more frightened, not less, with his incessant note-taking and his uncompromising legal jargon. He crooked a long white finger at her and, as if in a trance, she came and sat beside him at his small table.

Seated opposite them at another small table, on the other side of the central table, sat a couple of women. One, a peroxide blonde, was dressed snappily in a black suit and crisp white blouse, and she was busily sticking Post-it notes onto various of the papers in the pile in front of her. Her bright red nail varnish glinted in the strip-lighting and she glanced up, briefly, on Alice’s entry. Her companion, clad in sombre grey, was absorbed in making bold horizontal strokes with a luminous marker on the paper in front of her. She was highlighting key passages in the document, completing her last-minute preparations. Looking at the two lawyers, Alice decided that the one in the black suit must be her adversary, the Presenting Officer – the prosecutor, in ordinary parlance.

In front of the large, south-facing window was a long table at which the panel was seated. The Chairman, Chief Superintendent Jim McLay, sat in the centre, and his assessors, Superintendents Docker and Scrafe, were arranged on either side of him like bookends. Decades ago, McLay had played rugby for Scotland, but his prodigious muscle had long since turned to fat and a single seat no longer contained him adequately. By chance, his companions were both unusually small, looking like a couple of pet monkeys beside him. This odd trio were huddled together in conversation, with the two superintendents leaning inwards towards the big man as if to catch his every word, now being imparted in a low resonating rumble. The clerk, another lawyer, sat alone at a table to their left and he appeared alert, like a sprinter hunched on his blocks, ready for the proceedings to begin. His eyes were fixed on the Presenting Officer.

The first witness called by the prosecution was the Sex Offender Management Officer. The man could not disguise his nervousness, although he was well acquainted with legal proceedings and had competently given evidence in both the High Court of Justiciary and the Sheriff Court many times throughout his career. And those were intimidating settings, courtrooms decked in wooden panelling with a colourful Royal Coat of Arms above the bench, places where black-robed macers whispered to bewigged clerks and judges in red robes sat on high, surveying their domains. But in this stuffy little conference room he was unable to decide where to put his hands, alternately hiding them behind his back and then swinging them forwards where they hung loosely, chimp-like, in front of his groin. His unease was because here, in the Lothian and Borders headquarters, he was giving evidence against his own colleagues and in front of very senior officers. The latter were the very sort of men who might hold his own career in their hands. They would be judging him too, scrutinising him and his performance.

In a strong Aberdeenshire accent, he provided the panel with details of Reginald Alexander Longman, trawling through his record of previous convictions and, finally, explaining the regime currently applicable to high-risk sex offenders such as him, released on licence. Longman, he told them, had been tagged, was subject to twice-weekly checkups and was required to remain resident at an address in Causewayside.

Listening to him, Alice heard nothing that she had not already known on the day that fateful telephone call had come in to the St Leonard Street Station. The call that had begun it all, the garbled ten-minute conversation reporting a sexual assault on a little boy in the Ratcliffe Terrace area. The checks she had immediately run on the intelligence database and the criminal history system had produced precisely the sort of information that she was now hearing from the lips of this nervous constable. A catalogue of horror stretching over two decades, and for which Longman was responsible.

As a result of that intelligence, she and DS Stevenson had gone to check up on him at his address in Grange Loan. Not a street in the well-known leafy suburb of the Grange, a sizeable reservoir of New Club members, but its twin in name alone, a run-down place in a far less salubrious part of the capital. The street was narrow and mean, punctuated with graffiti-daubed wheelie bins, and, crucially, led off into Ratcliffe Terrace. And the proximity of Longman’s home to the scene of the offence seemed an unlikely coincidence. From a past encounter, Alice already knew what he looked like.

Finding the man’s home deserted, they knocked on all the neighbouring doors, trying to find out if anyone had seen or heard anything useful, anything that would help them with the investigation. Most doorways had paint peeling and a broken or nameless doorbell. From many of the houses they got no reply, despite bright lights inside and the curtains twitching on their approach. Curiosity alone was not enough to prompt a response, not when there was rent owing, the TV unlicensed and sheriff officers to keep at bay.

The sound of a dog barking greeted them in the common stairwell of the next tenement along. The steps themselves smelt of stale cooking, vomit and burnt plastic. Climbing them, DS Stevenson held his nose, gagging as he reached the second-floor landing.

There, when speaking to the inhabitants of the only occupied flat on it, he had, inadvertently, prefixed Longman’s name with the word ‘paedo’. From the expression of horror on the faces of the middle-aged couple it was immediately clear that neither of them had realised that their next-door neighbour was, as the man put it, a ‘fucking kiddy-fiddler’.

‘We’ve got bairns who come here!’ the woman had added crossly, looking outraged.

The word had soon spread. Later that very evening, reports of a rabble attacking Longman’s home and breaking down his door had come into the St Leonard’s switchboard. Nothing of the man had been seen since. Now underground and, to date, untraceable, he had assaulted another child, this time a little girl in the Niddrie area of the city, and a live warrant had been issued for his arrest.

After answering a number of questions from the panel, the witness was attempting to explain how vulnerable sex offenders such as Longman were while living in the community, describing in graphic detail a previous attack on the man when his identity had been discovered by a colleague at work. He had been attacked with a broken bottle, its jagged edge gouging a hole in his forehead the size of a two pence piece. On another occasion, and at another address, his home had been set alight and he had received second-degree burns to his arms and legs while escaping the blaze.

None of the windows in the conference room were open, and as the hours passed, the air temperature was becoming increasingly uncomfortable. Sweat was now apparent in beads on the constable’s forehead and the clerk had removed his jacket, hanging it neatly on the back of his chair. Alice too, was feeling the heat.

‘Any further questions, Miss Howard?’ the Chief Superintendent asked.

The black-suited lawyer shook her head. ‘None, Sir,’ she replied, closing her notebook with a businesslike snap.

‘Your witness, Mr Norton,’ McLay said, addressing Alice’s lawyer.

‘No questions, Sir,’ the man replied, scratching the side of his nose with his forefinger, then bobbing up and down on his seat as if in a courtroom.

The next witness, Alice knew, was vital to her cause, and she, along with everyone else in the room, hung onto to every word of his examination-in-chief.

‘Aye,’ the man from the neighbouring tenement said, ‘I remember the police coming and asking us questions. They took my parking space.’

‘Mr Meldrum, did either of the police officers speaking to you mention the fact that Mr Longman was a sex offender – in fact, refer to him as a “paedo”?’ Miss Howard inquired, against a backdrop of complete silence.

‘Aye.’

Alice held her breath. On the reply made to the next question by this plump, red-faced man, her whole career might hang. The Chief Super was leaning over his table, his eyes glued to the witness’s face.

‘Which of them mentioned that fact? Was it the male or the female police officer?’

‘Em . . . I’m pretty sure it was the man. He done all the talking.’

Alice heaved a sigh of relief and caught Alan Norton’s eye. He blinked owlishly at her, smiling slightly, and then returned to his assiduous note-taking.

The next witness was the previous witness’s wife. She entered the conference room and looked round it fearfully, registering that all eyes in the place were fixed upon her. She was dressed in an overly tight cream suit. Under one arm she clutched a beige handbag. It was her Sunday best, but the heels she had chosen to go with the ensemble were higher than those she usually wore to church. She had calculated that she would not have to walk too far, so there would be no danger of keeling over in them, as she had once done en route to the Ladies in the bingo hall. On TV programmes, her only insight into trials, witnesses stood still to give their evidence. She answered the questions in a faint, smoke-scarred voice and had to be warned by the chairman to speak up on three separate occasions. Finally, the crucial question was posed to her.

‘Did either of the police officers you spoke to mention the fact that Mr Longman was a sex offender, either of them call him a “paedo”?’

She nodded her head by way of a reply, and had to be advised once more by Chief Superintendent McLay that for the sake of the recording they needed an audible answer.

‘Aha,’ she confirmed, her voice almost too low to be made out.

‘Which one mentioned it, Mrs Meldrum – was it the man or the woman?’

Once more, complete and intense silence reigned until, finally, it was broken by her stuttering reply. Miss Howard was staring at the woman like a hawk, all her attention and energy focused on her prey, willing her to give a particular answer. Her victory depended upon it.

‘It w . . . was . . . the m . . . man.’

For a second, shock transformed the black-suited lawyer’s expression, but she recovered quickly and, in an even tone, said, ‘You say that it was the man. Are you absolutely sure about that, Mrs Meldrum? Could it, in fact, have been the woman?’

‘Aye, it could’ve,’ the witness said, her bag now held across her chest as if to protect herself. ‘At first I thought it was her. But later me and Davie spoke about it, and I realised it wasn’t her, it was him. I’m dead sure of that now. Certain it was him. The first time she spoke, like, was to tell him to keep quiet. She said, “That’s enough, Bill”, or something like that.’

Unexpectedly, Alice felt a long arm extend across her back and pat her shoulder, and she turned to see her lawyer’s beaming face.

‘We should be fine now,’ he whispered conspiratorially to her, and then he returned his gaze to his opposite number. She was deep in discussion with her sidekick, and the clerk, having left his own table, appeared to be drawing something to the attention of the panel.

Giving evidence herself, for once in her career, Alice almost enjoyed the experience. She answered the critical question confidently and without hesitation: ‘I did not inform any of Mr Longman’s neighbours in Grange Loan or elsewhere that he was a sex offender, or a paedophile.’

She felt a little more nervous about the follow-up question. In a solemn tone, and looking straight at her, Alan Norton asked, ‘Did you hear your colleague, DS Stevenson, so inform the occupants of the second-floor flat next to Longman’s house, Mr and Mrs Meldrum?’

She had answered that particular question in her head on countless earlier occasions, in the office in St Leonard’s Street, in the supermarket, while driving her car and in every room in her flat. Usually, incandescent with anger at her predicament, she had almost shouted out the word, ‘Yes!’ But here, now, at this hearing, she found herself hesitating. Even if the bastard had lied throughout the investigation in the full knowledge that she would be dragged into the proceedings, it went against the grain to ‘tell’ on him, inform against him. But if she did not do so then her own career might still be brought to a premature end, despite her innocence. And he would have no such bloody scruples. He had dropped her into this mess, and had this coming. So, loudly and as if she felt no qualm, she responded, ‘Yes.’

After a short interval during which Alice put her hands behind her head, leant back on her chair and tried to relax, the two female lawyers began conversing in hushed voices, both of them suddenly looking tired and rather grim. Eventually, the black-suited one stood up and turned to address the Chief Superintendent. Glancing down at a bit of paper she was holding in her hand, she said, ‘In all the circumstances, Sir, including the evidence given by Mr and Mrs Meldrum and DS Rice’s own testimony, the prosecution move that the hearing be discontinued and that DS Alice Rice be found Not Guilty on all the charges laid against her.’

With the collapse of the first hearing, the timetable for the second was brought forward. The proceedings against DS Stevenson were to begin straight away. Looking out through the open doorway of the interview room, Alice saw his unmistakable snub-nosed profile as he proceeded down the corridor on his way to the Force Conference Room. Trying to read that day’s copy of The Times, she could still overhear the voices of the Meldrums as they discussed what they would have for their tea later. Mrs Meldrum wanted a pizza and Mr Meldrum said that he would prefer a proper fry-up with eggs, bacon, sausages, black pudding and beans. Unable to agree, their voices got higher and higher, until footsteps could be heard followed by a harsh admonishment. There was a momentary silence, then a muted, ‘Fine. Right. Well, I’ll cook my own tea then!’ from Mr Meldrum.

The next sound that Alice heard was more footsteps, two sets this time, heading in the direction of the hearing. She peered out of her room and caught sight of the departing figure of Mr Meldrum, a minder leading him along as if he was a child.

Her mind drifted onto Reginald Longman, still on the loose, no doubt sheltered as usual by some smitten woman, ignorant of his predilections and with a child in tow. The infant would be the draw for him, something unimaginable to its mother, until the worst happened and the cycle began again.

It was so easy for him. He did not resemble the tabloid caricature of a paedophile, an inadequate with thick glasses and a woolly hat pulled down over a Neanderthal forehead. Looking into his eyes at their last interview, Alice had been horrified how attractive he had seemed to her, making her doubt for a second that they had apprehended the right man. But the contents of his computer had shattered any first impression that he had made. And the mask had slipped when he saw her as he was being escorted from court, his face contorting in fury, spitting at her like a snake.

Attempting to put the image of him out of her mind, she picked up her paper and started to read it again, homing in on an article about the plight of the Siberian tiger. Forty minutes later, hearing the sound of more footsteps, she peeped out again and came face to face with Mrs Meldrum as she was being shepherded away to give her evidence. She would be next, Alice thought, and she prayed inwardly that the Meldrums would not, for some reason or other, change their testimony.

This time when Alice entered the conference room she was directed to take a seat close to the door, facing the large table and opposite the panel. Annigoni’s picture of Queen Elizabeth wearing the Garter robes looked down regally upon the proceedings, the Prussian blue of her cloak now a little faded by sunlight. Alice was aware that William Stevenson was looking at her. His colour was not good and he appeared anxious, an uncharacteristic pleading expression in his eyes.

Once more she gave her evidence efficiently, describing the call, her investigations following upon it, the drive with DS Stevenson and finally their inquiries in Grange Loan. The Presenting Officer in the Stevenson case, another lawyer, was an untidy, grey-haired woman with specks of dandruff on her shoulders. She had the confident swagger of a battle-scarred fiscal, an old-timer who could cope with whatever emerged in the evidence. Looking relaxed, she introduced the ‘house to house episode’ as she called it.

‘DS Rice. Did you at any stage mention the fact that Reginald Longman was a sex offender, a paedophile in fact, to either Mr or Mrs Meldrum?’

‘No, I did not,’ Alice replied.

‘Did you . . .’ the woman asked, holding the lapels of her crumpled, navy suit as if it was a gown, ‘hear DS Stevenson tell either of the Meldrums that Mr Longman was a sex offender, a paedophile?’

‘I did.’ Alice answered quickly, deliberately avoiding meeting her colleague’s eye.

‘What expression did he use?’

‘Paedo.’

DS Stevenson shook his head from side to side in an exaggerated fashion, signalling to everyone present that she was not telling the truth and should not be believed.

Giving evidence in his own defence, he maintained, as he had throughout all the investigations, that he had not told the Meldrums that Longman was a paedophile but that his fellow sergeant, DS Rice, had done so. Foolishly, he felt the need to embellish the scene and was soon reporting other conversations with the couple, unaware that in the previous hearing they had said that the meeting on the landing had finished almost as soon as it had begun.

Once all the evidence had been taken, the panel listened to the Senior Officer’s report. Alice, who had remained in the room, was surprised to hear in the course of it that Stevenson had already picked up two regulation warnings in his sixteen-year career. One, a breach of regulation five, was for a trivial neglect of duty, and the other, a breach of regulation six, for misconduct involving the sexual harassment of a female colleague. Everyone in the room knew that the verdict was a foregone conclusion, so the Chief Superintendent surprised nobody when he finally delivered it in his booming baritone. Solemnly, and now sweating copiously in the heat, he declared that William Stevenson was required to resign in relation to both counts. Then, mopping his brow with his damp handkerchief, he rose and strode out of the room, the assessors following behind him like puppy dogs, desperate to keep up with their master’s gigantic strides.

The drive home did not take long despite the rush hour traffic or, if it did, Alice was not aware of it. The elation she now felt made everything seem bright and blessed, and she could find fault with nothing. With her hands resting loosely on the steering wheel and with the radio playing an old Beach Boys hit, she set off, feeling as if a great weight had been lifted from her shoulders. She had survived, been left with no stain on her character and the system had worked. No more accusations, no more questions, and life, normality, could be resumed at last.

Looking across Carrington Road onto the east elevation of Fettes College, the edifice as picturesque as a French chateau with its lofty central tower straining to touch the sky, she felt only pleasure. The immense building appeared as benign and well ordered as the world itself now seemed to be.