1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

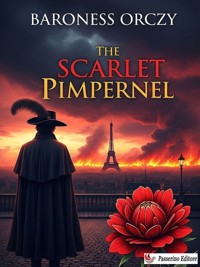

Set against the tumultuous backdrop of the French Revolution, Baroness Orczy's "The Scarlet Pimpernel" captivates with its blend of adventure, romance, and social commentary. The narrative artfully weaves together elements of suspense and intrigue, encapsulated in the tale of an elusive Englishman, Sir Percy Blakeney, who adeptly rescues aristocrats from the guillotine under the guise of a seemingly frivolous dandy known as the Scarlet Pimpernel. Orczy's lyrical prose and vivid characterizations breathe life into both the heroic exploits and the dramatic tensions inherent in revolutionary France, offering readers insight into the socio-political complexities of the era. Baroness Orczy, born in Hungary and later residing in England, was deeply influenced by her experiences during a time of political upheaval. Her family's aristocratic roots and her own formative years in a war-torn Europe inspired her to explore themes of loyalty, bravery, and sacrifice. Moreover, Orczy's theatrical background imbued her storytelling with a flair for drama and visual spectacle, making her work both engaging and reflective of the age's collective anxieties. Recommended to readers who appreciate classic literature imbued with thrilling escapades and deeper moral questions, "The Scarlet Pimpernel" is not merely a historical novel but a profound exploration of identity, freedom, and heroism. This timeless tale resonates with contemporary themes of justice and the fight against tyranny, promising an unforgettable journey for fans of adventure and romance in literature. In this enriched edition, we have carefully created added value for your reading experience: - A succinct Introduction situates the work's timeless appeal and themes. - The Synopsis outlines the central plot, highlighting key developments without spoiling critical twists. - A detailed Historical Context immerses you in the era's events and influences that shaped the writing. - An Author Biography reveals milestones in the author's life, illuminating the personal insights behind the text. - A thorough Analysis dissects symbols, motifs, and character arcs to unearth underlying meanings. - Reflection questions prompt you to engage personally with the work's messages, connecting them to modern life. - Hand‐picked Memorable Quotes shine a spotlight on moments of literary brilliance. - Interactive footnotes clarify unusual references, historical allusions, and archaic phrases for an effortless, more informed read.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

The Scarlet Pimpernel

Table of Contents

Introduction

In an age when a whisper could mean the guillotine, courage slips a mask over its face and leaves a flower behind. Baroness Orczy’s The Scarlet Pimpernel begins in the fevered tumult of the French Revolution and follows a clandestine contest of wits in which mercy, daring, and deception decide fates. Its emblem—a modest wildflower—becomes a signature of audacity, a quiet defiance etched against a backdrop of fear. The novel draws readers into a world where appearances conceal intentions, and where the most potent weapon is ingenuity. From its first pages, it promises suspense, romance, and the drama of impossible choices.

Set chiefly during the Reign of Terror, the story spans foggy English coasts and perilous Parisian streets, contrasting drawing-room elegance with the clang of tumbrils. Disguises, secret messages, and midnight journeys drive a narrative that thrives on reversals and close escapes. Orczy orchestrates a taut cat-and-mouse game between a hidden rescuer and the agents of a ruthless new order, grounding the thrill in moral stakes rather than spectacle alone. The result is an adventure that pivots on resourcefulness and nerve, where the smallest slip can cost a life and the smallest token can restore hope.

Baroness Emmuska Orczy, a Hungarian-born British novelist and playwright, first conceived The Scarlet Pimpernel for the stage in 1903 before expanding it into a novel published in 1905. Emerging in the Edwardian era, the work blended popular theatrical flair with the pace of modern popular fiction. Orczy’s intention was to captivate audiences with an exciting tale of chivalry, romance, and intrigue, while exploring how character is revealed under extreme pressure. The play’s success helped propel the novel, which quickly found an eager readership. These origins shape the book’s design: vividly staged confrontations, cliffhangers, and a keen sense of timing.

At its core, the book follows a mysterious English nobleman who, under a concealed persona, orchestrates daring rescues of prisoners destined for execution. He leads a small, loyal band whose ingenuity and courage challenge a formidable revolutionary apparatus. A relentless adversary, representing the new regime’s implacable will, presses from the other side, seeking to unmask the elusive mastermind. Orczy builds her scenes from covert meetings, coded tokens, and perilous crossings, always balancing danger with wit. Without disclosing secrets the story carefully unveils, it is enough to say that identity—hidden, assumed, and revealed—forms the engine that drives every turn.

The Scarlet Pimpernel is widely regarded as a cornerstone of modern adventure fiction because it helped crystallize the hero with a secret identity—an archetype that has resonated through later literature and popular culture. Its masked rescuer, double lives, and symbolic calling card established patterns that subsequent writers have adapted, repurposed, and expanded. The novel also influenced the burgeoning traditions of espionage, swashbuckling romance, and pulp narrative, demonstrating how suspense and moral purpose can coexist. By wedding theatrical set pieces to a brisk prose tale, Orczy created a durable template: a charismatic protagonist battling tyranny by outthinking rather than overpowering foes.

Part of the book’s classic appeal lies in its craft. Orczy’s background in theater infuses the novel with vivid staging, rhythmic dialogue, and a sense of scenes composed to crest at a reveal. She alternates intimate social encounters with high-stakes escapes, letting readers breathe between hazards without releasing tension. The contrasts—silk and steel, salon and scaffold—are carefully arranged to heighten drama. Her prose favors clear momentum over ornament, keeping the focus on motive and action. The recurring flower emblem unifies the plot, transforming a fragile bloom into a sign of nerve and finesse that threads through each deception and rescue.

Beneath the cloak-and-dagger adventure, the novel asks enduring questions about identity, loyalty, and conscience. What do we owe one another when the law turns harsh and ideology hardens into fear? How do masks protect—and imperil—the person who wears them? Orczy’s characters navigate conflicts between public duty and private feeling, between safety and responsibility, between cleverness and compassion. The book weighs justice against mercy, exposing the costs of both. It treats courage not as fearlessness, but as a deliberate choice to act despite risk, and it views heroism as equal parts presence of mind, moral clarity, and imaginative improvisation.

The historical frame is essential. By situating the action in revolutionary France, Orczy places readers where slogans and tribunals can invert long-held norms overnight. The novel filters that upheaval through a British lens typical of its time, contrasting imagined national temperaments while dwelling on universal human predicaments. It is less a documentary portrait of the period than a romance of peril and gallantry set amid the Revolution’s terrors. This vantage allows the author to explore how zeal, fear, and vengeance distort civic ideals, and how empathy—however unfashionable—can challenge the machinery of punishment in moments when it seems least welcome.

Orczy populates her story with figures designed for tension and interplay: an enigmatic leader whose anonymity is his shield, loyal companions who relish a dare, watchful adversaries who measure traps by intelligence rather than brute force, and civilians caught between loyalty and survival. Their exchanges hinge on wit and timing, using misdirection as both defense and art. Relationships strain and strengthen under suspicion and danger, reflecting the novel’s fascination with trust. Even amid grim circumstances, flashes of humor and irony keep tragedy from saturating the narrative, sharpening the sense that style—poise under fire—is itself a weapon.

Upon publication, The Scarlet Pimpernel quickly transcended its stage origins, inspiring sequels and a long legacy of adaptations for stage, film, radio, and television. Its central conceits—the secret league, the emblematic signature, the duel of intellects—proved remarkably adaptable, ensuring continual revivals and retellings. Readers have returned to it for more than a century, drawn by its brisk plotting and its marriage of romance and intrigue. The novel’s influence can be traced across popular storytelling traditions that prize clever ruses, moral determination, and theatrical flair, confirming its status as a foundational work in twentieth-century adventure literature.

For contemporary audiences, the book remains lively and accessible: quick turns, memorable set pieces, and a narrative confidence inherited from the theater. Some elements reflect the assumptions of its era, particularly in class and national portrayals, inviting discussion alongside enjoyment. As historical fiction filtered through romantic adventure, it offers both momentum and matter to consider. Readers who love mysteries, spy tales, and swashbuckling exploits will find familiar pleasures in its codewords and close shaves, while others may value its ethical questions. It stands at a fruitful crossroads where entertainment, character, and history meet without exhausting one another.

Ultimately, The Scarlet Pimpernel endures because it distills a thrilling idea: that ingenuity and compassion can outmaneuver terror. Its drama of masks and motives explores how public roles and private convictions collide, and how courage becomes contagious through example. The novel evokes suspense, wit, and a romantic faith in daring, yet it anchors those qualities in moral inquiry rather than spectacle alone. In an age fascinated by identity—online and off—its themes feel newly pertinent. Orczy’s creation continues to invite readers to ask what bravery looks like, whom it serves, and how a single emblem can kindle hope.

Synopsis

Set in 1792 during the French Revolution's Reign of Terror, The Scarlet Pimpernel opens amid relentless executions and mass fear. A mysterious Englishman, known only by the tiny wildflower he uses as his sign, leads a small league of gentlemen who smuggle condemned aristocrats to safety. Their daring rescues, executed with disguises and bold ruses, leave French authorities frustrated and vengeful. Rumor magnifies the leader into legend while the Committee of Public Safety intensifies its hunt. After an early escape succeeds, the narrative shifts across the Channel, where grateful refugees arrive in England and the agents of the revolution prepare countermeasures.

In Dover, at a busy coaching inn called the Fisherman's Rest, the effects of these exploits are felt firsthand. Refugees from France, including members of a prominent family, find protection and assistance from sympathetic English patrons. Among their helpers are young aristocrats who speak admiringly of the elusive leader and pass along messages sealed with the emblem of a small red flower. The innkeeper and staff witness the comings and goings of travelers, soldiers, and gossip. Here, admiration for the rescuer grows, but the peril also follows close behind, as news arrives of French agents determined to expose the network.

London society then comes into focus, where fashion, wit, and political opinion mingle. Lady Marguerite Blakeney, once a celebrated French actress, is admired for her intelligence and charm. Her husband, Sir Percy Blakeney, appears a wealthy, indolent fop whose idle talk masks an emotional distance in their marriage. Marguerite's beloved brother, Armand St. Just, moves in circles sympathetic to justice and mercy for victims of the Terror. Old grievances also surface: a French countess blames Marguerite for past denunciations that led to tragedy, straining social ties. This glittering milieu provides a sharp contrast to events across the Channel and frames impending intrigue.

Into this setting steps Citizen Chauvelin, a shrewd envoy of the revolutionary government, tasked with unmasking the Scarlet Pimpernel. He recognizes that information, not force, may yield success. Learning of Armand's vulnerability, he pressures Marguerite to cooperate by threatening her brother with arrest. The bargain is clear: help identify the rescuer, and Armand will be spared. At a grand ball hosted by a cabinet minister, secret communications are exchanged amid the crowd. Marguerite glimpses compromising clues, and Chauvelin secures intelligence pointing to a planned rendezvous in northern France. The contest between hunter and elusive quarry sharpens, and the stakes become personal.

Marguerite faces a dilemma that drives the middle of the novel. She must protect her brother without condemning a man whose courage has saved many lives. Her marriage, distant and constrained by misunderstanding, offers little guidance. She searches for a way to warn the intended victim and the rescuer while concealing her involvement from Chauvelin. Clues suggest that key participants will leave for the coast under innocuous pretexts. Despite her hesitation, events move quickly, and her actions, meant to shield Armand, help set the pursuit in motion. The tension tightens as all paths converge toward the Channel and impending danger.

The scene shifts to northern France, particularly the port of Calais and a wayside inn called Le Chat Gris. Chauvelin arrives with orders, soldiers, and informants, determined to ensnare his adversary. Marguerite follows, traveling in secrecy, and begins piecing together the plan from fragments overheard in the taproom and street. Local figures, including an innkeeper, a quiet boatman, and a Jewish peddler, add bustle and complication to the crowded setting. Reports speak of a hidden meeting place near the shore and of an important prisoner to be rescued. Tide tables, patrol routes, and passwords become decisive tools in the unfolding pursuit.

Chauvelin organizes a trap using surveillance, bribery, and sudden raids, hoping to seize both the fugitives and their English savior. Watchers are posted around the inn and along the coastal paths. Marguerite, now fully aware of the stakes, risks exposing herself to get a warning to the intended recipients. The rendezvous is set for nightfall near an isolated hut by the beach, where smugglers often land. Fog, wind, and the pull of the tide complicate movements and timetables. Meanwhile, rumors of disguises and decoys suggest that the rescuers may be closer than they seem, testing the patience of the hunters.

The climax unfolds through a series of rapid encounters in darkness, as identities, loyalties, and intentions collide. Quick improvisation and misdirection shape the outcome of meetings in the hut and on the shore. Marguerite becomes directly involved in the peril, showing resolve as she navigates between opposing forces. Without disclosing decisive revelations, the sequence advances toward a desperate bid for escape by sea. The confrontation forces characters to reassess trust and allegiance, altering relationships that seemed fixed earlier. The immediate crisis in France reaches a turning point, with fate hinging on timing, courage, and the thin margin between discovery and flight.

The conclusion restores attention to England and to the social world that now reads the Scarlet Pimpernel as both myth and man. Some lives are secured, and the legend of the league grows through whispered anecdotes and new plans. The narrative underscores themes of bravery, ingenuity, and loyalty amid political violence. It contrasts surface appearance with hidden purpose, particularly within marriage and friendship, and shows how wit can outmaneuver force. Although individual secrets remain protected within the story, its central message is clear: steadfast compassion and calculated daring can resist oppression. The tale ends with poise, leaving the hero's mystique intact for future exploits.

Historical Context

Set principally between 1792 and 1794, The Scarlet Pimpernel moves between revolutionary France and Georgian Britain. Paris, the epicenter of political upheaval, supplies the atmosphere of tribunals, watch committees, and the guillotine at the Place de la Révolution. Northern France, especially the port of Calais and the Pas-de-Calais coastline, provides the liminal space where fugitives attempt escape across the Channel. On the English side, Dover and the Kentish coast, along with London’s aristocratic salons, present a contrasting world of relative order under George III. This dual geography, connected by packet boats and clandestine craft, frames the novel’s interplay of peril, pursuit, and refuge.

The time is marked by swift ruptures in sovereignty, surveillance, and allegiance. France transitions from constitutional monarchy to republic; Britain navigates a wartime posture without domestic revolution. London’s elite circles, including the Prince of Wales’s milieu and the Foreign Secretary Lord Grenville’s social sphere, coexist with relief committees for French refugees. By contrast, Parisian streets, neighborhood sections, and revolutionary tribunals enforce ideological conformity. The Channel itself functions as a political boundary and a contested corridor. Inns, coaching roads, and coastal watch stations become sites of espionage and evasion, while the proximity of Calais and Dover makes flight and pursuit logistically plausible.

The Reign of Terror, conventionally dated from September 1793 to July 1794, shaped the political climate dramatized in the novel. Directed by the Committee of Public Safety (established 6 April 1793), it centralized authority under leaders such as Maximilien Robespierre, Louis-Antoine de Saint-Just, and Georges Couthon. The Revolutionary Tribunal in Paris, created 10 March 1793, expedited political justice. Official tallies record roughly 16,000 executions by guillotine across France and perhaps 40,000 deaths including extra-judicial killings. The Place de la Révolution (today Place de la Concorde) became the iconic site of state violence. Orczy’s plot of desperate rescues implicitly responds to this machinery of summary condemnation.

Terror’s legal instruments enabled mass suspicion and rapid sentencing. The Law of Suspects (17 September 1793) broadened the categories of those liable to arrest, from nobles to anyone lacking civic zeal. The Law of 22 Prairial Year II (10 June 1794) curtailed defendants’ rights, reducing trials to swift verdicts. Surveillance relied on neighborhood sections, watch committees, and mandatory tricolor cockades. Provincial atrocities compounded the toll: drownings at Nantes, fusillades at Lyon, and mass executions by mobile commissions. In the novel, checkpoints, identity papers, cockades, and public carts transporting prisoners evoke these institutional practices, while the Pimpernel’s forged documents and disguises contest the state’s omnipresent scrutiny.

Beyond executions, the Terror completed a social revolution begun in 1789. Hereditary titles and armorial bearings were abolished on 19 June 1790; biens nationaux, confiscated church and émigré properties, reshaped ownership. Economic regulation accompanied repression, notably the General Maximum (September 1793). Dechristianization campaigns closed churches and introduced the Revolutionary calendar, backdated to 22 September 1792; Robespierre’s Festival of the Supreme Being followed on 8 June 1794. These measures targeted aristocrats and clergy as symbols of the Old Regime. The novel’s recurring scenes of nobles hustled in charrettes to the scaffold and frantic efforts to evade committees illustrate the social inversion and fear that such policies produced.

The Terror’s roots lie in the radicalization of 1789–1792. Key watersheds include the storming of the Bastille (14 July 1789), the royal family’s Flight to Varennes (20–21 June 1791), and the Champ de Mars massacre (17 July 1791). On 10 August 1792, the Tuileries Palace fell, ending the monarchy’s effective authority; the September Massacres (2–6 September 1792) killed roughly 1,100–1,400 prisoners in Paris. The National Convention proclaimed the Republic on 21 September 1792. Orczy situates her narrative near these turning points, when revolutionary fervor, prison overcrowding, and mob justice made noble families’ fates precarious, and when clandestine flights from Paris to Channel ports became urgent.

The trial and execution of Louis XVI galvanized Europe. The Convention began proceedings in December 1792; the king was condemned and guillotined on 21 January 1793 in the Place de la Révolution. Marie Antoinette, transferred from the Temple to the Conciergerie, was tried 14–16 October 1793 and executed on 16 October. Madame Élisabeth followed on 10 May 1794. Earlier, the Princess de Lamballe was murdered during the September Massacres (3 September 1792). These high-profile deaths intensified émigré flight and foreign intervention. In the novel’s background, the monarchy’s fall heightens the peril to aristocrats and underscores why covert networks risked life to extract prisoners awaiting judgment.

The Committee of Public Safety, created 6 April 1793 and empowered from July 1793, coordinated war, internal security, and supply. Alongside it, the Committee of General Security managed policing and surveillance. Measures such as the levée en masse (23 August 1793) mobilized the nation for war; the Maximum regulated prices and wages. Representatives on mission enforced compliance in the provinces. Orczy’s antagonist, Citizen Chauvelin, embodies this centralized coercion. Historically, a real Bernard-François, marquis de Chauvelin served as French envoy in London until his expulsion in January 1793; the novel fuses the diplomat’s name with the Committee’s police powers to dramatize revolutionary state reach.

The émigré exodus profoundly altered Britain’s social landscape. Between 1789 and 1794, an estimated 130,000–160,000 French men and women fled, including perhaps 25,000–30,000 clergy. London, Dover, and provincial towns like Bath hosted communities sustained by charity. The British Relief of the French Refugees Committee formed in 1793, with contributions from aristocratic patrons and congregations. The Prince of Wales and Whig circles mingled curiosity and sympathy for displaced nobles. In the novel, London balls, drawing rooms, and discreet safe houses replicate this milieu; the Pimpernel’s league of English aristocrats channels private philanthropy into operational rescue, reflecting contemporary aid transformed into clandestine action.

War framed cross-Channel relations. France declared war on Austria on 20 April 1792 and on Great Britain and the Dutch Republic on 1 February 1793. Britain expelled the French envoy Chauvelin on 24 January 1793 after refusing to recognize him post-monarchy. Notable campaigns included Valmy (20 September 1792) and Jemappes (6 November 1792), and at sea the Royal Navy’s victory in the Glorious First of June (1 June 1794). The Channel was patrolled and often blockaded, yet small craft still plied between Calais and Dover. The novel capitalizes on this contested maritime zone, situating pursuit and evasion within wartime diplomacy and naval surveillance.

British domestic policy tightened during the crisis. William Pitt the Younger served as prime minister, overseeing the Aliens Act of 1793, which required foreign arrivals to register and restricted movement. After domestic radical scares, Parliament suspended habeas corpus in 1794, and the Treason Trials that autumn tested the limits of dissent, though juries acquitted the accused. Lord Grenville, Foreign Secretary from 1791, anchors the governmental elite; Orczy places a pivotal ball in his social orbit, with the Prince of Wales present. This juxtaposition of ceremony and state vigilance situates the Pimpernel’s operations amid surveillance of foreigners and fears of French agents in London.

Escape depended on logistics as much as daring. Travel from Paris to Calais followed post roads with relay stations for horses, using berlines or public diligences. Revolutionary sections scrutinized passports and demanded tricolor cockades. The Dover–Calais packet crossing could take three to six hours in fair weather; storms or patrols extended risk. Kent’s Romney Marsh and the Downs teemed with smugglers adept at evading customs and coast guards, a real infrastructure for clandestine movement. Orczy’s Fisherman’s Rest in Dover, coastal caves, and carts of disguised fugitives reflect period realities of inns, beach launches, and forged papers navigating committees and shoreline sentries.

Revolutionary symbolism reshaped daily life. The Republic standardized the address citizen, promoted the red Phrygian cap, and enforced display of the tricolor. The Revolutionary calendar, officially adopted on 24 November 1793 and backdated to 22 September 1792, renamed months and decimated weeks into décades. Dechristianization closed churches, removed crosses, and sometimes converted sacred spaces to temples of Reason. Later, Robespierre sponsored the Cult of the Supreme Being with a festival on 8 June 1794. In Orczy’s scenes, the ubiquitous citizen, cockades, and processions to the scaffold register these cultural shifts, while British settings preserve Anglican rites and Georgian custom as a counterpoint.

Counterrevolution and provincial repression intensified the cycle of violence. The Vendée uprising began in March 1793, forming the Catholic and Royal Army; Republican forces under General Westermann and, in 1794, Turreau’s infernal columns devastated the region. Lyon, after rebellion, endured siege (August–October 1793) and mass executions under Collot d’Herbois and Joseph Fouché. At Nantes, Jean-Baptiste Carrier orchestrated drownings in late 1793. These episodes reveal a nationwide system of coercion extending beyond Paris. The novel’s references to revolutionary zealots in towns, impromptu tribunals, and hostile checkpoints in northern France mirror the broader climate of suspicion and reprisals in regions far from the capital.

The Thermidorian Reaction ended the Terror’s legal framework. On 9 Thermidor Year II (27 July 1794), Robespierre and allies were arrested; on 10 Thermidor (28 July) they were guillotined. The Law of 22 Prairial was repealed on 1 August 1794, and prisoners were gradually released. A White Terror in 1795 targeted former Jacobins; the royalist rising of 13 Vendémiaire Year IV (5 October 1795) was suppressed by Bonaparte, ushering in the Directory. Orczy’s narrative, set in the Terror’s apex, leverages this historical arc by dramatizing maximum peril before moderation. Later sequels would gesture toward shifting political landscapes, but the first novel fixes the pre-Thermidor stakes.

The book operates as a critique of revolutionary justice and the politics of virtue. It depicts how emergency decrees erode due process, turning suspicion into conviction and civic zeal into persecution. By staging rescues that restore individuals to legal protection in Britain, it contrasts rule of law with the arbitrariness of exceptional tribunals. The anonymous hero, a noble who rejects performative privilege for clandestine service, rebukes both hereditary complacency and ideological extremism. Surveillance committees, forced symbols, and politicized trials expose the fragility of rights when citizenship becomes conditional upon orthodoxy and the state weaponizes fear as a tool of governance.

The portrayal of British high society adds a secondary critique. Orczy satirizes frivolous elites whose idleness masks moral capacity, challenging assumptions that birth equals virtue. The League’s cross-class cooperation suggests a civic ethic beyond titles, while French scenes condemn the inversion of justice through class revenge and demagoguery. The spectacle of the guillotine, mobs, and coerced language illustrates how performative patriotism displaces compassion and law. Diplomats, committees, and informers demonstrate how national security can mutate into repression. Through juxtaposed capitals, the novel exposes class divides, state overreach, and ideological absolutism, arguing for moderation, private conscience, and humane restraint amid revolutionary crisis.

Author Biography

Baroness Orczy (Emmuska Orczy) was a Hungarian-born British novelist and playwright active from the late Victorian era into the mid-twentieth century. She is best known for creating the Scarlet Pimpernel, a daring rescuer who hides his identity behind aristocratic frivolity, a figure that helped define the masked-avenger archetype in popular fiction. Working primarily in English after settling in Britain, Orczy produced historical romances, adventure tales, and early detective stories that enjoyed wide readership and frequent reprints. Her work bridged the popular stage and the novel, and its brisk plotting and theatrical flair made her a pillar of Edwardian popular culture.

Born in Hungary in the 1860s, Orczy spent parts of her youth on the Continent before her family made a permanent home in London in the 1880s. She trained as an artist at London institutions such as the West London School of Art and Heatherley’s, initially aspiring to a career in illustration. The discipline of drawing and a visual sense of composition shaped her later scene-building for stage and page. Immersed in the multilingual, cosmopolitan milieu of fin-de-siècle London, she absorbed the appeal of historical romance and melodrama, with writers like Alexandre Dumas and the conventions of the popular theatre leaving a lasting mark.

Orczy published early fiction in magazines and issued several novels before finding her breakthrough in the early 1900s with The Scarlet Pimpernel as a stage play. She devised the plot and, with her husband, the artist Montagu Barstow, shaped the script for initial provincial try-outs that led to a triumphant London run. She quickly adapted the material into a novel, consolidating the character’s fame beyond the theatre. The story’s mixture of peril, disguises, and ironic wit resonated with audiences, and the author swiftly became associated with brisk, cliffhanging narratives set against the convulsions of the French Revolution.

Building on that success, Orczy expanded the Pimpernel universe across sequels, prequels, and linked story collections for several decades. Titles such as I Will Repay, The Elusive Pimpernel, El Dorado, and The Laughing Cavalier elaborated the hero’s circle and lore while varying historical backdrops and intrigues. The books were commercial hits, translated widely, and repeatedly reissued, even as some critics regarded them as unabashed melodrama. Their energy, clever reversals, and romantic idealism secured a loyal readership, and stage revivals and screen versions kept the franchise in public view, reinforcing the character’s status as a touchstone of swashbuckling fiction.

Alongside her revolution-era adventures, Orczy became a notable figure in early crime fiction. The Old Man in the Corner stories introduced an armchair sleuth who unraveled mysteries in a café, influencing the subgenre of ratiocinative detection without violence. She also created Lady Molly of Scotland Yard, one of the earlier female detectives in English fiction, foregrounding observation and tenacity over brute force. Orczy continued to write stand-alone historical romances and short fiction for magazines, demonstrating facility with episodic structure and serial publication. Her range across mystery and historical adventure broadened her audience and helped secure steady publication throughout the 1910s and 1920s.

Orczy’s fiction reflects a pronounced sympathy for order and hierarchy, casting the upheavals of the French Revolution as a backdrop against which personal honor and courage are tested. Aristocrats and royalists often receive sympathetic treatment, while zealotry and mob violence are portrayed as destructive forces. These stances, consistent across her historical narratives, aligned with strands of conservative and royalist sentiment in her time and informed her choice of themes: disguise as moral performance, loyalty under pressure, and the saving power of ingenuity. The clarity of her moral universe, while unfashionable to some critics, contributed to the stories’ narrative drive.

She remained productive into the interwar years and later published an autobiography, Links in the Chain of Life, reflecting on her craft and career. Orczy died in England in the 1940s, by which time The Scarlet Pimpernel had become a durable property with numerous stage and screen incarnations. Today her work is read as foundational to the masked-hero tradition and as an early chapter in the development of popular detective fiction. Readers continue to value her pacing, theatricality, and memorable conceit of the double life, while scholars situate her within the broader currents of Edwardian popular culture and historical romance.

My wife is a demmed clever woman

"Get out with you and with your plague-stricken brood!" shouted Bibot hoarsely.

Now then Sally, me girl, now then!...stop that fooling with them young jackanapes

"My Lord Tony himself."

May God protect you all, Messieurs."

"Nay, there is no time, Sir Percy."

"You would in any case be my own brave sister."

"Pretty women...ought to have a good time in England..."

"Allow me, Comtesse, to introduce to you, Lady Blakeney..."

"And you believed them then and there..."

The incidents referred to in the images below could not be identified in the text.

"The agent or spy of the French Government—the man Chauvelin, I mean— is on my track!"

"La! he seems ill-tempered, and methought he had such an engaging countenance.""

Cover of an early edition.

A surging, seething, murmuring crowd of beings that are human only in name, for to the eye and ear they seem naught but savage creatures, animated by vile passions and by the lust of vengeance and of hate. The hour, some little time before sunset, and the place, the West Barricade, at the very spot where, a decade later, a proud tyrant raised an undying monument to the nation's glory and his own vanity.

During the greater part of the day the guillotine had been kept busy at its ghastly work: all that France had boasted of in the past centuries, of ancient names, and blue blood, had paid toll to her desire for liberty and for fraternity. The carnage had only ceased at this late hour of the day because there were other more interesting sights for the people to witness, a little while before the final closing of the barricades for the night.

And so the crowd rushed away from the Place de la Grève and made for the various barricades in order to watch this interesting and amusing sight.

It was to be seen every day, for those aristos were such fools! They were traitors to the people of course, all of them, men, women, and children, who happened to be descendants of the great men who since the Crusades had made the glory of France: her old noblesse. Their ancestors had oppressed the people, had crushed them under the scarlet heels of their dainty buckled shoes, and now the people had become the rulers of France and crushed their former masters—not beneath their heel, for they went shoeless mostly in these days—but a more effectual weight, the knife of the guillotine.

And daily, hourly, the hideous instrument of torture claimed its many victims—old men, young women, tiny children until the day when it would finally demand the head of a King and of a beautiful young Queen.

But this was as it should be: were not the people now the rulers of France? Every aristocrat was a traitor, as his ancestors had been before him: for two hundred years now the people had sweated, and toiled, and starved, to keep a lustful court in lavish extravagance; now the descendants of those who had helped to make those courts brilliant had to hide for their lives—to fly, if they wished to avoid the tardy vengeance of the people.

And they did try to hide, and tried to fly; that was just the fun of the whole thing. Every afternoon before the gates closed and the market carts went out in procession by the various barricades, some fool of an aristo endeavoured to evade the clutches of the Committee of Public Safety. In various disguises, under various pretexts, they tried to slip through the barriers, which were so well guarded by citizen soldiers of the Republic. Men in women's clothes, women in male attire, children disguised in beggars' rags; there were some of all sorts: ci-devant counts, marquises, even dukes, who wanted to fly from France, reach England or some other equally accursed country, and there try to rouse foreign feelings against the glorious Revolution, or to raise an army in order to liberate the wretched prisoners in the Temple, who had once called themselves sovereigns of France.

But they were nearly always caught at the barricades; Sergeant Bibot especially at the West Gate had a wonderful nose for scenting an aristo in the most perfect disguise. Then, of course, the fun began. Bibot would look at his prey as a cat looks upon the mouse, play with him, sometimes for quite a quarter of an hour, pretend to be hoodwinked by the disguise, by the wigs and other bits of theatrical make-up which hid the identity of a ci-devant noble marquise or count.

Oh! Bibot had a keen sense of humour, and it was well worth hanging round that West Barricade, in order to see him catch an aristo in the very act of trying to flee from the vengeance of the people.

Sometimes Bibot would let his prey actually out by the gates, allowing him to think for the space of two minutes at least that he really had escaped out of Paris, and might even manage to reach the coast of England in safety, but Bibot would let the unfortunate wretch walk about ten mètres towards the open country, then he would send two men after him and bring him back, stripped of his disguise.

Oh! that was extremely funny, for as often as not the fugitive would prove to be a woman, some proud marchioness, who looked terribly comical when she found herself in Bibot's clutches after all, and knew that a summary trial would await her the next day and after that, the fond embrace of Madame la Guillotine.

No wonder that on this fine afternoon in September the crowd round Bibot's gate was eager and excited. The lust of blood grows with its satisfaction; there is no satiety; the crowd had seen a hundred noble heads fall beneath the guillotine to-day; it wanted to make sure that it would see another hundred fall on the morrow.

Bibot was sitting on an overturned and empty cask close by the gate of the barricade; a small detachment of citoyen soldiers was under his command. The work had been very hot lately. Those cursed aristos were becoming terrified and tried their hardest to slip out of Paris: men, women and children, whose ancestors, even in remote ages, had served those traitorous Bourbons, were all traitors themselves and right food for the guillotine. Every day Bibot had had the satisfaction of unmasking some fugitive royalists and sending them back to be tried by the Committee of Public Safety, presided over by that good patriot, Citoyen Foucquier-Tinville.

Robespierre and Danton both had commended Bibot for his zeal and Bibot was proud of the fact that he on his own initiative had sent at least fifty aristos to the guillotine.

But to-day all the sergeants in command at the various barricades had had special orders. Recently a very great number of aristos had succeeded in escaping out of France and in reaching England safely. There were curious rumours about these escapes; they had become very frequent and singularly daring; the people's minds were becoming strangely excited about it all. Sergeant Grospierre had been sent to the guillotine for allowing a whole family of aristos to slip out of the North Gate under his very nose.

It was asserted that these escapes were organised by a band of Englishmen, whose daring seemed to be unparalleled, and who, from sheer desire to meddle in what did not concern them, spent their spare time in snatching away lawful victims destined for Madame la Guillotine. These rumours soon grew in extravagance; there was no doubt that this band of meddlesome Englishmen did exist; moreover, they seemed to be under the leadership of a man whose pluck and audacity were almost fabulous. Strange stories were afloat of how he and those aristos whom he rescued became suddenly invisible as they reached the barricades and escaped out of the gates by sheer supernatural agency.

No one had seen these mysterious Englishmen; as for their leader, he was never spoken of, save with a superstitious shudder. Citoyen Foucquier-Tinville would in the course of the day receive a scrap of paper from some mysterious source; sometimes he would find it in the pocket of his coat, at others it would be handed to him by someone in the crowd, whilst he was on his way to the sitting of the Committee of Public Safety. The paper always contained a brief notice that the band of meddlesome Englishmen were at work, and it was always signed with a device drawn in red—a little star-shaped flower, which we in England call the Scarlet Pimpernel. Within a few hours of the receipt of this impudent notice, the citoyens of the Committee of Public Safety would hear that so many royalists and aristocrats had succeeded in reaching the coast, and were on their way to England and safety.

The guards at the gates had been doubled, the sergeants in command had been threatened with death, whilst liberal rewards were offered for the capture of these daring and impudent Englishmen. There was a sum of five thousand francs promised to the man who laid hands on the mysterious and elusive Scarlet Pimpernel.

Everyone felt that Bibot would be that man, and Bibot allowed that belief to take firm root in everybody's mind; and so, day after day, people came to watch him at the West Gate, so as to be present when he laid hands on any fugitive aristo who perhaps might be accompanied by that mysterious Englishman.

"Bah!" he said to his trusted corporal, "Citoyen Grospierre was a fool! Had it been me now, at that North Gate last week..."

Citoyen Bibot spat on the ground to express his contempt for his comrade's stupidity.

"How did it happen, citoyen?" asked the corporal.

"Grospierre was at the gate, keeping good watch," began Bibot, pompously, as the crowd closed in round him, listening eagerly to his narrative. "We've all heard of this meddlesome Englishman, this accursed Scarlet Pimpernel. He won't get through my gate, morbleu! unless he be the devil himself. But Grospierre was a fool. The market carts were going through the gates; there was one laden with casks, and driven by an old man, with a boy beside him. Grospierre was a bit drunk, but he thought himself very clever; he looked into the casks—most of them, at least—and saw they were empty, and let the cart go through."

A murmur of wrath and contempt went round the group of ill-clad wretches, who crowded round Citoyen Bibot.

"Half an hour later," continued the sergeant, "up comes a captain of the guard with a squad of some dozen soldiers with him. 'Has a car gone through?' he asks of Grospierre, breathlessly. 'Yes,' says Grospierre, 'not half an hour ago.' 'And you have let them escape,' shouts the captain furiously. 'You'll go to the guillotine for this, citoyen sergeant! that cart held concealed the ci-devant Duc de Chalis and all his family!' 'What!' thunders Grospierre, aghast. 'Aye! and the driver was none other than that cursed Englishman, the Scarlet Pimpernel.'"

A howl of execration greeted this tale. Citoyen Grospierre had paid for his blunder on the guillotine, but what a fool! oh! what a fool!

Bibot was laughing so much at his own tale that it was some time before he could continue.

"'After them, my men,' shouts the captain," he said after a while, "'remember the reward; after them, they cannot have gone far!' And with that he rushes through the gate followed by his dozen soldiers."

"But it was too late!" shouted the crowd, excitedly.

"They never got them!"

"Curse that Grospierre for his folly!"

"He deserved his fate!"

"Fancy not examining those casks properly!"

But these sallies seemed to amuse Citoyen Bibot exceedingly; he laughed until his sides ached, and the tears streamed down his cheeks.

"Nay, nay!" he said at last, "those aristos weren't in the cart; the driver was not the Scarlet Pimpernel!"

"What?"

"No! The captain of the guard was that damned Englishman in disguise, and everyone of his soldiers aristos!"

The crowd this time said nothing: the story certainly savoured of the supernatural, and though the Republic had abolished God, it had not quite succeeded in killing the fear of the supernatural in the hearts of the people. Truly that Englishman must be the devil himself.

The sun was sinking low down in the west. Bibot prepared himself to close the gates.

"En avant. The carts," he said.

Some dozen covered carts were drawn up in a row, ready to leave town, in order to fetch the produce from the country close by, for market the next morning. They were mostly well known to Bibot, as they went through his gate twice every day on their way to and from the town. He spoke to one or two of their drivers—mostly women—and was at great pains to examine the inside of the carts.

"You never know," he would say, "and I'm not going to be caught like that fool Grospierre."

The women who drove the carts usually spent their day on the Place de la Grève, beneath the platform of the guillotine, knitting and gossiping, whilst they watched the rows of tumbrils arriving with the victims the Reign of Terror claimed every day. It was great fun to see the aristos arriving for the reception of Madame la Guillotine, and the places close by the platform were very much sought after. Bibot, during the day, had been on duty on the Place. He recognized most of the old hats, "tricotteuses," as they were called, who sat there and knitted, whilst head after head fell beneath the knife, and they themselves got quite bespattered with the blood of those cursed aristos.

"Hé! la mère!" said Bibot to one of these horrible hags, "what have you got there?"

He had seen her earlier in the day, with her knitting and the whip of her cart close beside her. Now she had fastened a row of curly locks to the whip handle, all colours, from gold to silver, fair to dark, and she stroked them with her huge, bony fingers as she laughed at Bibot.

"I made friends with Madame Guillotine's lover," she said with a coarse laugh, "he cut these off for me from the heads as they rolled down. He has promised me some more to-morrow, but I don't know if I shall be at my usual place."

"Ah! how is that, la mère?" asked Bibot, who, hardened soldier that he was, could not help shuddering at the awful loathsomeness of this semblance of a woman, with her ghastly trophy on the handle of her whip.

"My grandson has got the small-pox," she said with a jerk of her thumb towards the inside of her cart, "some say it's the plague! If it is, I sha'n't be allowed to come into Paris to-morrow." At the first mention of the word small-pox, Bibot had stepped hastily backwards, and when the old hag spoke of the plague, he retreated from her as fast as he could.

"Curse you!" he muttered, whilst the whole crowd hastily avoided the cart, leaving it standing all alone in the midst of the place.

The old hag laughed.

"Curse you, citoyen, for being a coward," she said. "Bah! what a man to be afraid of sickness."

"Morbleu! the plague!"

Everyone was awe-struck and silent, filled with horror for the loathsome malady, the one thing which still had the power to arouse terror and disgust in these savage, brutalised creatures.

"Get out with you and with your plague-stricken brood!" shouted Bibot, hoarsely.

And with another rough laugh and coarse jest, the old hag whipped up her lean nag and drove her cart out of the gate.

This incident had spoilt the afternoon. The people were terrified of these two horrible curses, the two maladies which nothing could cure, and which were the precursors of an awful and lonely death. They hung about the barricades, silent and sullen for a while, eyeing one another suspiciously, avoiding each other as if by instinct, lest the plague lurked already in their midst. Presently, as in the case of Grospierre, a captain of the guard appeared suddenly. But he was known to Bibot, and there was no fear of his turning out to be a sly Englishman in disguise.

"A cart,..." he shouted breathlessly, even before he had reached the gates.

"What cart?" asked Bibot, roughly.

"Driven by an old hag...A covered cart..."

"There were a dozen..."

"An old hag who said her son had the plague?"

"Yes..."

"You have not let them go?"

"Morbleu!" said Bibot, whose purple cheeks had suddenly become white with fear.

"The cart contained the ci-devant Comtesse de Tourney and her two children, all of them traitors and condemned to death."

"And their driver?" muttered Bibot, as a superstitious shudder ran down his spine.

"Sacré tonnerre," said the captain, "but it is feared that it was that accursed Englishman himself—the Scarlet Pimpernel."