7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Telegram Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

'All wars are alike. What I experienced in Lebanon, others experienced in France, in Spain, in Yugoslavia, or elsewhere. Yes, all wars are alike, because while weapons change, the men who wage and are subjected to war do not in the least.' Alexandre Najjar was eight when Lebanon erupted into a bloody and brutal conflict; he was twenty-three when the guns at last fell silent. After seven years of voluntary exile spent clearing his mind from the unbearable nightmare of civil war, he is now back amongst his family and friends, and the past is quickly catching up with him. As he reacquaints himself with his bullet-riddled city, Alexandre is haunted by vivid memories, which he sets down with extraordinary imagination and humour. Sometimes nostalgic, and sometimes brutal and shocking, "The School of War" offers unforgettable insights into the experience of childhood in war.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

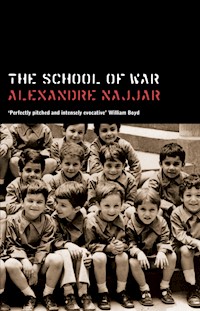

Alexandre Najjar

The School of War

Translated from the French by Laurie Wilson

TELEGRAM

To the memory of Robert Najjar

Contents

Prologue

Esthetics of the Shell

Fireworks

Snipers

The Barber

Loving

Under Fire

Home-schooling

The Bullet

Water

The Corpse

The Radio

The Candle

Grenades

The Shelter

Roadblocks

Gas

One Shell All

Alcohol

The Long Vacation

The Hospital

Refugees

Car Bombs

The Schoolteacher

Epilogue

Prologue

All wars are alike. What I experienced in Lebanon, others experienced in France, in Spain, in Yugoslavia or elsewhere. Yes, all wars are alike, because while weapons change, the men who wage and are subjected to war do not in the least. As a child, I sometimes heard my Uncle Michel talk about ‘Big Bertha’. I thought he was talking about an aunt or a distant cousin. It was not until later – much later – that I understood that he had appropriated the nickname given to an enormous German howitzer during the Great War, so he could talk about the war without frightening us. ‘Big Bertha’ … Eighty years later, on the brink of the third millennium, in a country located on the shores of the Mediterranean, the same code-name, the same ugly war, the same tragedy.

When I resolved to return to Lebanon, after a seven-year absence, I was seized by a double sense of anxiety: that of seeing the past catch up with me, and that of being disappointed by the postwar situation. I had left the Country of Cedars after fifteen years of having, with all my strength, resisted a violence that spared nothing. I had frequented the war like one frequents a lady of the night, had drained my cup to the last dregs. Once peace had been re-established, I had decided to go elsewhere for a breath of fresh air, as if, my mission accomplished, I suddenly felt the need to clear my mind, to forget the drama I had endured, under another sky.

The war was an unbearable nightmare for me, but was also – how could I deny it? – an excellent schooling in life’s lessons. Hemingway said that ‘any war experience is priceless for a writer.’ I would like to believe that. Without the war, I would have been another man. All my life, I will undoubtedly regret not having had a peaceful childhood (I was eight when the war broke out, twenty-three when the guns were silenced) and having often seen death from too short a distance. But these regrets, these trials, have given me a new understanding of happiness. A day without bombings, a bridge that isn’t under sniper siege, a night without a blackout, a road without barricades, a clear sky across which no rockets shoot … for me, all of this will henceforth be synonymous with happiness.

As for ‘Bertha’, now that I know the truth, I prefer to believe, as I did as a child, that she is a plump old lady who strolls through the streets in her big white hat, smiling at children and handing out candy to them.

Beirut, June 1999

Esthetics of the Shell

‘Ahlan wa sahlan!’

Aunt Malaké greets me, and I give her a kiss and enter the living room, walking into a heavy aroma of tobacco and honey.

‘You still smoke your narghile?’

‘It’s my favorite pastime,’ she replies, shrugging her shoulders.

Nothing has changed in this house: the slightly outdated furniture, the painting of the opera singer Umm Kulthum, the black-and-white portrait of Uncle Jamil, and the cat hair on the blue carpet. On a coffee table, near the buffet, a bouquet of white roses in a cylindrical container.

‘What is that?’

‘A shell case. It’s decorative, don’t you think?’

‘Decorative’ … This word takes me back fifteen years. The first shell, like a baptism.

The first shell was lying at the base of a 240mm gun mounted in a schoolyard in Achrafieh. Around the gun stood three permanently assigned militiamen who, on a day of truce, invited me to share their snack. Until then, I had thought shells were invisible – I saw them explode far off in the distance in a geyser of smoke, encircle the bombed villages with an ephemeral halo, set houses and pine forests ablaze; I heard their din as they crashed down on my neighbourhood, or their whistle as they sliced through the air over the house … To see a shell, to caress it, was a revelation for me. With its oblong, esthetically faultless form, its generous curves, its nose cone that recalls the contours of a breast, its elegant blue-grey colour, and the brilliance of its steel casing, polished like a piece of marble, a shell is beautiful, marked by perfect beauty. To the touch, it is cold and hard; who would believe it could explode into a thousand pieces? Oddly, it emits a sense of security. So who dreamed up this instrument that combines obesity and beauty so well? Was it to highlight the precariousness of all things beautiful or out of perfectionism that its creator took such care to polish this projectile that in the end disintegrates as it disseminates terror? I deduced that this unknown artist, along with the sniper, was among those who lend their art to the service of Death and who seek perfection in murder itself.