Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Barbara Cartland Ebooks Ltd

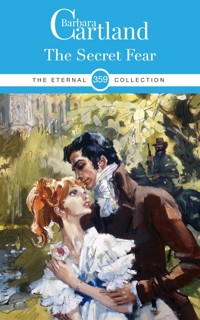

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: The Eternal Collection

- Sprache: Englisch

When the Marquis of Meridale returns to his castle after many years away, numerous surprises await him. This castle has fallen into rack and ruin and there is an atmosphere of fear surrounding it and everyone in it. Another surprise was Arabella, a wispy, outspoken girl who had been sent to Meridale Castle to be a companion to Lady Beulah. But Arabella was as baffling as well as beautiful. Why did she shrink from his touch? Why did she never speak of her past? And what was the dark secret that explained the aura of dread in his once-happy home? As the answers start to unravel, Arabella finds herself locked in a web of deceit and intrigue. And as they are plunged into terrifying danger, does the Marquis have the key to win her love, and free her from her secret fear?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 365

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Audiobooks

Listen to all your favourite Barbara Cartland Audio Books for free on Spotify, just scan this code or click here

THE LATE DAME BARBARA CARTLAND

Barbara Cartland, who sadly died in May 2000 at the grand age of ninety eight, remains one of the world’s most famous romantic novelists. With worldwide sales of over one billion, her outstanding 723 books have been translated into thirty six different languages, to be enjoyed by readers of romance globally.

Writing her first book ‘Jigsaw’ at the age of 21, Barbara became an immediate bestseller. Building upon this initial success, she wrote continuously throughout her life, producing bestsellers for an astonishing 76 years. In addition to Barbara Cartland’s legion of fans in the UK and across Europe, her books have always been immensely popular in the USA. In 1976 she achieved the unprecedented feat of having books at numbers 1 & 2 in the prestigious B. Dalton Bookseller bestsellers list.

Although she is often referred to as the ‘Queen of Romance’, Barbara Cartland also wrote several historical biographies, six autobiographies and numerous theatrical plays as well as books on life, love, health and cookery. Becoming one of Britain’s most popular media personalities and dressed in her trademark pink, Barbara spoke on radio and television about social and political issues, as well as making many public appearances.

In 1991 she became a Dame of the Order of the British Empire for her contribution to literature and her work for humanitarian and charitable causes.

Known for her glamour, style, and vitality Barbara Cartland became a legend in her own lifetime. Best remembered for her wonderful romantic novels and loved by millions of readers worldwide, her books remain treasured for their heroic heroes, plucky heroines and traditional values. But above all, it was Barbara Cartland’s overriding belief in the positive power of love to help, heal and improve the quality of life for everyone that made her truly unique.

One

There was a sound of footsteps in the hall and a small figure sped silently across the thick carpet to hide behind the long, velvet curtains framing the window. A second later the door of the library was opened and Arabella knew that her stepfather had entered the room.

She heard him throw his riding-whip down on the desk and then, with a feeling almost like sickness, realised she had left a book open in the armchair. She could almost see his sharp eyes under the dark, bristling eyebrows glance towards it, and he would notice the rosewood library steps below the place in the cabinet from which the book had been extracted.

She held her breath, feeling that at any moment he might suspect her presence in the room and start to look for her. Then, with a sense of relief, she heard her mother come in.

“Oh, there you are, Lawrence,” Lady Deane exclaimed in her soft, low voice. “I thought I heard your horse outside. Did you have a good ride?”

“Arabella has been here!” Sir Lawrence announced dramatically, his harsh voice seeming to echo round the room. “I understood she was too indisposed to leave her room.”

“Indeed, she is still far from well,” Lady Deane said hastily, “and I am sure she cannot have come downstairs.”

“Do you see that book?” Sir Lawrence demanded. “If I’ve told my stepdaughter once, I’ve told her a thousand times, I will not have her reading my books. Many of them are not fit for a young girl, and besides, too much learning is not good for the young. But she has disobeyed me, as she has disobeyed me so often before.”

“Now, Lawrence, pray do not distress yourself,” Lady Deane begged. “I will speak to Arabella.”

“I will speak to Arabella,” Sir Lawrence thundered.

There was a moment’s silence before Lady Deane said agitatedly,

“I do beg you not to be incensed with her! And if you are thinking of whipping her as you have done before, she is not well enough. Indeed, Lawrence, she is too old for that sort of thing.”

“She is not too old to misbehave!” Sir Lawrence retorted. “And if she does what she has been told not to do, then she must take the consequences.”

“Lawrence, I beg of you…” Lady Deane began, only to be interrupted by her husband.

“We will speak of this no more. You will send Arabella to me first thing tomorrow morning. There is not time now, we leave for the Lord Lieutenant’s at five o’clock.”

After a pause, as if Lady Deane was forcing herself to cease the argument, she said in a low voice that trembled,

“Do you really consider it wise that I should wear the diamond tiara tonight, Lawrence, and my other jewels? All the county knows that his party is to take place and I am convinced that terrible gang of highwaymen will be lying in wait for the guests.”

“Everything has been taken care of, my dear,” Sir Lawrence answered loftily. “You will wear your tiara and not perturb yourself about these cut-throats.”

“But Lawrence, you remember the last time I lost my ruby parure, and the villains even dragged the rings from my fingers! I have never suffered such fear or such humiliation!”

“Nor I!” Sir Lawrence said frankly. “But what could I do? I was unarmed and there were six of them. And that damned felon, Gentleman Jack or whatever he calls himself, had the effrontery to jeer at me. One day I shall watch him swing for that! I swear to you, Felicity, it will be the happiest day of my life!”

Sir Lawrence spoke with such venom in his voice that Lady Deane gave a little cry of protest.

“No, no! You must not speak like that, Lawrence! It frightens me. These men are all you say they are, but their crimes, abominable though they may be, must not inflame you until you would be as brutal as they are.”

It seemed that her words softened Sir Lawrence’s fury because, when he spoke again, his voice was gentler.

“All woman, aren’t you, Felicity? And not a bad thing to be, either. I cannot abide these hard-swearing, hard-riding, modern young females, who pretend they have no need of masculine protection. But all the same it is a disgrace that two years after the war with Bonaparte is ended, we cannot have more soldiers to deal with this scourge upon our countryside. Why, His Honour the Judge himself was waylaid on his way back from the assizes. They took his watch and his ring and fifty guineas that his Marshal carried, in gold, to pay for their lodging on circuit.”

“The Judge!” Lady Deane exclaimed. “Will nothing deter them?”

“It’s just sheer incompetence that they have not been apprehended before now.” Sir Lawrence stormed. “In the last century highwaymen terrorised the whole countryside – but today, in 1817, we should have thought out new methods to bring them to justice. What we need is a company of Dragoons, and I shall tell the Lord Lieutenant so myself this very evening!”

“That is if we ever reach the party,” Lady Deane said apprehensively. “Oh, Lawrence! Pray do not make me wear the tiara. It is so conspicuous!”

“It will be quite safe,” Sir Lawrence assured her, “and you would feel sadly inconspicuous if you appeared without it. There is a chance – but only a chance, mind you – that His Royal Highness will be present.”

“His Royal Highness? You mean to say the Regent will be there this evening?” Lady Deane cried.

“Well, Lady Hertford has accepted an invitation, and we know full well where Lady Hertford goes, Prinny will follow,” Sir Lawrence said. “So put on your best bib and tucker, Felicity. I would not have you put out of countenance by any lady of the Carlton House set. They may be all the crack, my dear, but they cannot hold a candle to you when it comes to looks!”

“Lawrence, you flatter me!” Lady Deane said softly. “But you are right. Of course I must wear my jewels. I am thankful now I ordered a new gown from Bond Street for this very occasion, though indeed it was wretchedly expensive.”

“I want to be proud of you,” Sir Lawrence said. “Damn it all! Those who wondered why I chose to marry a widow rather than a fresh-faced maid shall have their answer tonight. You are in good looks, my dear!”

“I will try to do you credit,” Lady Deane answered sweetly. “And now I had best go and prepare myself.”

“Have no longer any fears for the safety of either yourself or your tiara,” Sir Lawrence said. “I have made special arrangements for the journey. We drive in convoy.”

“In convoy? What does that mean?” Lady Deane enquired.

“Colonel Travers will start first and drive the short distance to The Towers, where Lord and Lady Jeffreys will be waiting with their coachman and footman, both armed, and also two outriders. The carriages will proceed here and we shall join then. I am arranging that there will be two footmen on our coach and both grooms will come on horseback. That way we shall have seven armed men and six outriders. What think you of my clever scheme?”

“It is indeed clever,” Lady Deane enthused. “Only you could have organised it so thoroughly. Dear Lawrence, how fortunate I am to be the wife of a man with such a brain.”

“Between us we have both beauty and brains,” Sir Lawrence said with satisfaction. “Run along, my dear. We must not keep Her Ladyship waiting.”

“No, indeed,” Lady Deane agreed, moving towards the door.

“And do not forget to tell Arabella,” Sir Lawrence went on, “that I will speak with her tomorrow morning.”

Lady Deane paused.

“There is something I have to tell you, Lawrence,” she said, “and I hope you will not be incensed. I have arranged to send Arabella away.”

There was a moment’s silence, and then, with a note of ominous irritation in his voice, Sir Lawrence said loudly,

“You have arranged to send her away without consulting me?”

“Naturally I was going to speak with you about it,” Lady Deane said. “When Doctor Simpson was here today...”

“Simpson? Who the hell is Simpson?” Sir Lawrence shouted.

“He is the new doctor,” Lady Deane replied. “You recall that our old physician, Doctor Jarvis, has retired. He had a stroke and I fear he will not recover. Well, Doctor Simpson, a younger man, has taken over the practice.”

“Some nit-witted whippersnapper who thinks he knows everything, I suppose!” Sir Lawrence growled.

“He seems intelligent,” Lady Deane said, “and he was perturbed to find that Arabella was so thin and weak after her illness. Scarlet fever can be very lowering, Lawrence, as you well know.”

“Arabella is well enough to come downstairs, stealing my books,” Sir Lawrence muttered.

“Doctor Simpson had a suggestion,” Lady Deane went on bravely, ignoring the interruption. “He told me he was extremely anxious to find a companion for Beulah Belmont, and he suggested that Arabella might go to the castle for a short visit to give her a change of atmosphere and perhaps be of some help to poor little Beulah.”

“Poor little Beulah, indeed! A help to poor little Beulah!” Sir Lawrence guffawed. “Why the child’s an addle-brained idiot from all accounts! What good could Arabella do to her?”

“It’s Doctor Simpson’s idea that the child needs companionship. After all, as we all well know, there is no one at the castle except her governess and all those old servants.”

“While the Merry Marquis amuses himself in London, eh?” Sir Lawrence exclaimed. “Upon my soul, you can’t blame the man. Who would want to put up with that ramshackle old place? It ought to have been pulled down long ago.”

“Oh, Lawrence, how can you say such a thing? It’s just been sadly neglected since Lady Meridale died. Doctor Simpson feels that little Beulah may be dippy because she has never had the love of a mother.”

“Sickly, sentimental tosh!” Sir Lawrence growled. “The child’s said to be half-monster! If young Meridale wants someone to look after his sister, he should come home and arrange it himself. And as for Arabella going there, I have never heard such a nonsensical notion in the whole of my life. You’ve spoiled her and the girl is out of hand already. Wasting her time at the castle won’t do her or anybody else any good. And I’ll tell Doctor Know-All so myself when I meet him!”

“We’ll talk about it tomorrow,” Lady Deane said soothingly. “I must hurry now or, indeed, you will blush with shame at my appearance. And, besides, I do not wish to play the wallflower while all the most attractive women in the room cluster around you, Lawrence!”

The flattery brought a smile back to Sir Lawrence’s grim countenance. Nevertheless, when his wife left the room, he walked across to the chair and picked up the open book where Arabella had left it. He stood looking down at it pensively, then slapped it shut. There was still a faint smile on his lips, but it was very different from the one that had been evoked by his wife’s compliments. Indeed, there was something unpleasant and a little evil in the manner in which, while his eyes narrowed, he set the book down gently beside his riding-whip on the desk. For a moment he contemplated the two objects. Then with a little sound like a faint laugh he went from the room, closing the door behind him.

It was some moments before Arabella dared move. She was well aware that her stepfather, with his often-uncanny perception where she herself was concerned, might have closed the door to let her think he had gone, and remained inside the room to watch her emerge from her hiding-place. But she heard his footsteps cross the marble hall and only when they had died away, did she come from behind the curtain.

She was small-boned with delicate, etched features, but now she was unnaturally thin from the illness that had kept her in bed for over five weeks. It made her violet eyes seem enormous in her tiny, pointed face, and as she moved silently across the floor, she looked little more than a pathetic waif that needed feeding and cosseting back to health.

She opened the door a mere inch, saw that the hall was empty, and sped swiftly as a fleeting shadow, not up the front staircase, but down a side passage that led to the back stairs. Only when she reached the sanctuary of her own bedroom did some of the fear and tension go out of her face, and she sat, gasping for breath, on a stool in front of the dressing-table. But a knock at the door brought her swiftly to her feet again, her eyes wide and apprehensive.

“Who is it?” Her voice was hardly audible.

“’Tis me, Miss Arabella,” a voice replied.

“Oh, come in, Lucy.”

“Her Ladyship wants ye,” Lucy announced in a broad Hertfordshire accent.

She was an apple-cheeked young girl from the village who was being trained in the duties of fourth housemaid and found it exceedingly hard to remember all she had to do.

“I’ll go to her at once,” Arabella said, and added anxiously, “Is she alone, Lucy?”

“There be only Miss Jones with her,” Lucy replied, understandingly. “The Master be in his own room.”

“Thank you, Lucy,” Arabella said, moving swiftly towards her mother’s bedroom, which opened off the landing at the top of the staircase.

Lady Deane was sitting in front of her mirror and her lady’s maid was arranging a sparkling tiara on top of her elaborately ringleted hair.

“Mama, that looks lovely!” Arabella exclaimed spontaneously as she entered the room. “I adore you in your tiara. When I was a child, I thought you looked exactly like a fairy queen and I always expected to see wings sprouting from your shoulders.”

“How are you, darling?” Lady Deane asked. “I pray you have not over-tired yourself. Doctor Simpson said you were not to do too much the first few days you were out of bed.”

“I promise you, I have done very little,” Arabella replied.

She wondered if this would be the right moment to admit that she had been hiding in the library downstairs and decided against it. She knew only too well what awaited her tomorrow and how deeply it would distress her mother.

“I am nearly ready, Jones,” Lady Deane said to her maid. “Will you wait outside and tell me when Sir Lawrence goes downstairs? I want to talk to Miss Arabella.”

“Very good, My Lady,” Jones replied.

She was a middle-aged women, who had been with her mistress for over ten years and knew all the difficulties and crosscurrents that beset the household. With a sympathetic glance at Arabella she went from the room, closing the door behind her.

Lady Deane turned impulsively to her daughter.

“Listen, dearest,” she said, “we have not much time and there is so much I have to impart to you. I want you to leave here tomorrow morning early.”

“To go to the castle?” Arabella asked quickly.

Lady Deane looked up into her daughter’s face.

“You were in the library,” she said. “I half suspected it.”

“I do not think he knew I was there,” Arabella replied. “In fact, I am sure of it. If he had known, he would have ferreted me out when you left.”

“No, I am sure he was ignorant of your presence,” Lady Deane said. “But how could you have been so foolish as to leave the book behind?”

“I was not expecting him back so soon,” Arabella answered. “No, that is not the whole truth, Mama. I just became enthralled with what I was reading. You know how I forget everything, the time, the place, and even my stepfather, when I am reading.”

“You will have to leave before he punishes you,” Lady Deane said miserably. “You are not in a fit state to endure it. And I know that I could not stand by and see you suffer, as I have done in the past.”

Arabella was very still.

“It is not that I mind his whipping me,” she said in a low voice. “It is when he is pleasant that it is unbearable. Oh, Mama! How could you have married him?”

“He is kind to me, Arabella. And you forget that dear Papa left us completely penniless.”

“All that mad gambling!” Arabella said bitterly.

“He enjoyed it so much,” Lady Deane sighed, “and he was always so penitent when he lost. And when he won, what fun we used to have!”

“I know,” Arabella said. “I remember how he used to come home and call for a bottle of champagne. You used to give me a tiny sip and we would all laugh, and it seemed like the most wonderful party in the world. Then he would carry you off to London. Once I said to him, ‘What are you going to do, Papa, when you get to London?’ He picked me up in his arms and swung me above his head and replied, ‘Your Mama and I are going to spend money and have fun, Arabella. That is what life is for – for laughter, wine and fun. Not all this grumble, grumble about bills.’”

Lady Deane laughed.

“That sounds exactly like your father,” she said. “How he used to hate the bills and the grumble, grumble about them. And now he has not to worry anymore.”

For a moment Lady Deane closed her eyes, as though she would shut out everything but her memories. Then she said quickly,

“It is no use, Arabella. We cannot live in the past. I assure you that I am content with Sir Lawrence. It is only where you are concerned that I cannot control him.”

“I am sorry, Mama,” Arabella said.

“Oh, it is not your fault,” Lady Deane replied. “You are going to be very beautiful, Arabella, and beautiful women are always a disturbing influence where men are concerned.”

“I hate men!” Arabella cried. “I hate all of them! I hate the way they look at me. I hate the greedy, possessive expression on their faces, the way their hands go out towards me.”

She shuddered.

“Oh, Mama! I don’t want to grow up! I want to remain a child.”

“That is exactly what I want you to pretend to be,” Lady Deane answered.

“What do you mean?” Arabella asked curiously.

“Doctor Simpson has only seen you in the last week since he took over Doctor Jarvis’s practice,” Lady Deane answered. “You have been in bed, you have appeared so thin, small and very young, Arabella. He thinks you are still a child.”

“Is that why he has asked that I should go to the castle?” Arabella asked.

Lady Deane nodded.

“I imagine he believes you to be about twelve or thirteen. He inferred that and I did not contradict him.”

“Why not tell him the truth – that I shall be eighteen in a month’s time?” Arabella asked.

“If I had,” Lady Deane replied, “he would not have suggested that you visit the castle. It is not what I should want for you, Arabella, but you must get away from here.”

Arabella moved forward to play with the silver brush on her mother’s dressing-table.

“I did not think you had noticed, Mama,” she said quietly.

“Of course I noticed,” Lady Deane said. “I saw you growing prettier and prettier, Arabella, and I knew, too, that your stepfather was jealous of you where I was concerned. He always has been, and it gave him an excuse to punish you severely and cruelly at every possible opportunity. But as you grew older...”

“Do not let us talk of it, Mama,” Arabella begged in an anguished voice. “We understand, both of us, and as you say, I must go away.”

“I was wondering what to do. I have been wondering for a long time,” Lady Deane said, “and when Doctor Simpson suggested you might be a companion for poor little Beulah, I knew it would give us time to think. I have thought that perhaps you might visit your Godmother in Yorkshire, or your father’s aunt who lives in Dorset. It is just that I have lost touch with both of them. But now I will write to them and find out how they are, what are their circumstances, and if there is any possibility of their offering you hospitality for a long period. But tomorrow you must go to the castle.”

“I am a little vague about the castle and who lives there,” Arabella said.

“The Marchioness of Meridale died soon after her daughter, Beulah, was born,” Lady Deane said. “From all accounts, the child is not happy. She must be about seven or eight years old. But Doctor Simpson seems to think that if she were treated differently from the way she has been in the past, her mental faculties might improve. He appeared to think she was neglected at the moment.”

“Poor child,” Arabella exclaimed.

“I gather,” Lady Deane continued, “that the doctor has made a study of these unfortunate children and being young and enthusiastic he wants to try out his ideas. It won’t be very entertaining for you, Arabella, but I promise that I will try to move you from the castle as soon as possible.”

“Do not fret, Mama,” Arabella said. “It might be quite interesting. Who is the Merry Marquis?”

“The present Marquis of Meridale is, of course, Beulah’s brother,” Lady Deane replied. “I am afraid he has not a very enviable reputation. He was a soldier during the war, and these last two years everyone expected him to come home and make some improvements to his property. The farms are tumbling down. The tenant farmers grumble. The land wants money spending on it. But I gather His Lordship prefers his amusements in London where he is a member of the Carlton House set.”

“He sounds odious!” Arabella exclaimed. “But I shall not be troubled by His Lordship, it seems.”

“No, indeed,” Lady Deane agreed, “but do rest, Arabella, and try and get some colour back into your cheeks. Your hair – it used to be so lovely – looks lank and limp. But Doctor Simpson says that is always the result of a high fever. Anyway, please play the part that is expected of you, until I can make other arrangements. Oh, darling! I shall miss you so!”

Lady Deane held out her arms and drew her daughter close.

“You are all I have left of Papa,” she murmured almost inaudibly. “It is not easy to part with you, Arabella. But I know I am doing what is right. It is just that the house will be so empty – so very empty without you.”

“I love you, Mama,” Arabella said, “but I know you are correct in thinking I must go away.”

She found she could say no more – the words were choked in her throat. Then there came a knock at the door.

“The Master has gone downstairs, My Lady,” Jones said in a low voice.

“Then I must not keep him waiting,” Lady Deane said, disentangling herself from Arabella’s clinging arms and rising to her feet.

“He will be angry tomorrow, Mama,” Arabella warned. “He will not be pleased that his prey has escaped so easily!”

“I can handle him,” Lady Deane replied confidently. “In his own way, he loves me. The carriage will be waiting for you by the kitchen door, Arabella, at eight-thirty. Jones will help you pack. If I do not see you to say ‘goodbye’, you will know that I shall be thinking of you. I shall also be praying for you.”

“Do not worry about me, Mama,” Arabella said bravely.

Almost as though she could not bear to look at her daughter again, Lady Deane went from the room, the gems in her tiara sparkling in the light from the tapers. The room seemed curiously dark when she had left it. Arabella stood still, listening. She heard her stepfather’s voice in the hall and then the sound of carriage-wheels drawing up to the front door.

Arabella went to the window. Below her she could see three coaches with their painted panels, each drawn by a pair of well-matched horses, the silver on their harness sparkling in the light from the setting sun. The outriders with their powdered wigs and livery-caps all carried pistols, which she knew were loaded. The footman on the box of her stepfather’s coach had a blunderbuss across his knees.

‘At least the tiara is safe for tonight,’ Arabella thought with a little smile. The six highwaymen who had been terrorising the whole countryside would not dare attack such a formidable adversary.

The cavalcade moved off and Arabella watched them until they had moved out of sight down the drive. Then she turned back into the candlelit bedroom. Jones was snuffing out the candles.

“Her Ladyship will outshine them all,” she said.

“I only wish I could see her at the party,” Arabella said. “Do you think the Regent will really be there?”

“If the party’s grand enough, he will be,” Jones answered. “But there’s more things to be done in this country, Miss, than the giving of parties.”

“You are right, Jones,” Arabella agreed. “You would think he would want to see what was being done about the men returning from the wars – if they have homes to go to, and pensions for those who were wounded.”

“His Royal Highness leaves that sort of thing to the politicians,” the lady’s maid said sourly. “And from all accounts, they’re only jostling for power.”

Arabella gave a little sigh.

“I wish I knew more about what is taking place. I wish I could go to Parliament and listen to the speeches at Westminster. I wish I could talk to someone really seriously about these things.”

“That talk is not for females,” the maid said tartly. “Now, come along, Miss Arabella, we’ve got to decide what clothes you’re to take. Her Ladyship said I were to pack all the dresses you were wearing years ago and nothing that makes you appear your real age. You’ve lost so much weight, you’ll get into them all. ’Tis a blessing I kept ’em.”

“Oh, dear! I thought I had seen the last of those baby muslins,” Arabella sighed.

“Her Ladyship gave me her instructions,” Jones said primly.

“Very well then. It is no use asking me,” Arabella replied. “Pack what you wish. I do not expect to be at the castle long and anyway there will be nobody to look at me. At the same time, it will be rather an adventure.”

She went to bed thinking about the morrow and was awake long before Lucy came to call her with a cup of hot chocolate.

Arabella only sipped the chocolate and dressed herself quickly in the clothes that Jones had left ready. She could not help smiling at her appearance when she had finished. The dress, full and falling from a high yoke at the shoulders, made her look exactly the age that Doctor Simpson had thought her to be, if not younger. The soft, heelless slippers over white socks were very suitable for a child and so was the broad-brimmed hat, trimmed with pale blue ribbons and large, artificial daisies.

She parted her hair down the middle and let it fall on either side of her face. Once it had been like living gold, with fiery lights in it, in vivid contrast to the magnolia white of her skin. But her illness had dulled the gold and now the heavy tresses only seemed to accentuate the sharpness of her little chin and the tired lines under her large eyes.

‘Well, one thing is certain,’ Arabella thought to herself, ‘not even Sir Lawrence would look at me like this!’

It was as a woman that she had most feared him – as a child she had merely hated him for his brutality.

Ready, she said goodbye to Lucy and ran downstairs and through the kitchen quarters. As her mother had arranged, the carriage was waiting outside, and she got into it quickly, half afraid at the very last moment that her stepfather would come bellowing round the corner to prevent her escape.

They drove sedately down the back drive and out through the North Lodge onto the dusty road, which led away from the village and down ten miles of narrow, twisting lanes towards Meridale.

They passed through a small hamlet with its village green, on which stood the stocks, then Arabella had her first glimpse of the castle. She could see its castellated turrets over the tops of the trees, long before the drive, winding between an avenue of oak trees, led her to the full sight of it. Then, as it came into view, she gasped. She had expected from her stepfather’s description something ancient and crumbling. Instead, she saw a magnificent, awe-inspiring edifice of grey stone, set high on a hill but sheltered by a forest of dark trees.

It had originally been a Norman fortress, and though succeeding generations had enlarged it, Arabella thought the additions had increased, not diminished, its magnificence. As they drew nearer, she saw below the castle there was a lake, the water blue in its reflection of the sky above, and on it floated several white swans. They passed over a bridge, under which flowed the stream that fed the lake, then the coach drove onto a wide gravel sweep in front of an imposing nail-studded door, with a flight of stone steps leading up to it.

Arabella stepped out of the coach to stare about her, looking up towards the castle, which towered towards the sky. It must have been in the reign of Queen Anne, she thought, that the arrow slits had been replaced with tall square-paned windows.

After so much magnificence it seemed somehow incongruous to see in the doorway an old, very decrepit butler, rather untidily dressed, instead of a resplendent individual in keeping with the building.

“Good morning to ye, Miss. The doctor told us ye were a’coming,” the butler said in a surprisingly countrified voice. “But we didn’t expect ye so early.”

“I am sorry if it is inconvenient,” Arabella said quickly.

“’Tis not inconvenient to Oi,” the butler replied. “’Tis Miss Harrison Oi be a’thinking of. Her bain’t one for getting up early. But never mind, George’ll take ye up. Ye must excuse Oi, Miss, for not accompanying ye mysel’. M’legs ain’t what they used to be.”

“No, of course not, I quite understand,” Arabella assured him.

George was an equally uncouth footman, she thought. He was in his shirtsleeves, wearing a dirty striped waistcoat with crested silver buttons that badly needed cleaning. George was also unshaven, and she thought how outraged Sir Lawrence would have been if any of the footmen at home had dared to appear in such a guise.

“Take the young lady upstairs to the schoolroom, George,” the butler admonished, “and ye should have put yer coat on!”

“It be in the pantry,” George answered.

“Never mind then,” the butler said testily. “Oi dare say ye’ll be excused.”

Arabella said nothing. She was beginning to see that the absence of the Master of the castle had a deteriorating effect. It was not only the farms that had gone to waste. The dust was thick on the polished chairs and she thought it must have been a long time since anyone had thought to clean the windows. There was also a smell of damp, as though no one had bothered to air the place for a long time.

As they climbed higher, things got worse. The schoolroom was on the second floor and they passed along corridors and landings, set with fine furniture and magnificent pictures. But they were all grubby and unkempt. Arabella thought how her mother’s house always smelt of beeswax and lavender – the windows were open, the sunshine streamed in. Here the very air was stale and she felt her spirits droop long before they reached the second floor.

George stopped and knocked on a door. There was no answer and he knocked again.

“Oi doubt if her’ll be up yet,” he said.

“It is after nine-thirty,” Arabella said, who had noted on the last landing, a grandfather clock, that was actually working.

George did not bother to reply but opened the door, and by the light of a partially pulled back curtain Arabella could see that she was in a large, very comfortably furnished room. There was a fire burning in the grate – so somebody must have been there before them – perhaps the same housemaid who had pulled back one of the curtains so that she could see what she was doing. But the room was empty and George glanced towards a door on the further side.

“Ye’d best wait here,” he said. “Her may be asleep.”

“Please do not disturb Miss Harrison,” Arabella said quickly.

“Oi weren’t a’going to,” George said laconically and walked off, leaving Arabella standing in the centre of the room.

It was a curious welcome, but she felt that the fault lay in the expediency that had made her leave home so early. No one could be expected to anticipate visitors at nine-thirty in the morning.

Then a strange sound made her start. She was not certain what it was. But when it was repeated, she realised it came from under a large, round table in the middle of the room, which was covered by a fringed cloth reaching to the floor.

The sound came again, and now Arabella, overcome with curiosity, moved forward, lifted the edge of the cloth, and peeped underneath. There, sitting on the floor, was a child. She was in her white nightgown and in her arms she held two small kittens. Two others were on the floor beside her, drinking from a saucer of milk.

“Hush!” the child said, in a funny, lisping voice. “Beulah, not wake her.”

“I thought you must be Beulah,” Arabella said. “I am Arabella and I have come here to play with you.”

Two small eyes, almost like blue marbles, stared at her. Her head was too big for her body, her face was round, expressionless, almost moonlike. She was not exactly ugly, but her hair, cut short and standing almost on end, made her look unnecessarily strange.

“Ara ... bella,” Beulah repeated, hesitatingly.

“That is right,” Arabella smiled. “Why do you not come out so we can talk?”

“Beulah, not wake her,” the child replied. She repeated the words in a slow, staccato manner as if she had learnt them like a parrot.

“Do you mean your Governess?” Arabella asked. “No, of course not, that would be a mistake. Are those your kittens?”

Beulah nodded and held the animals in her arms even tighter, as if she thought Arabella would take them away. One of them miaowed and clawed at the child’s nightgown.

“They are very pretty,” Arabella said gently. “But I will not touch them as they are yours.”

Beulah’s round, marble eyes stared at her. Then impulsively she held out one of the kittens.

Arabella did not take it, she merely stroked it.

“You keep it,” she said. “It belongs to you.”

Beulah seemed satisfied with this. Then she said in a low whisper,

“Beulah, know secret. Beulah, not tell secret. Beulah ... promised!”

“That is right,” Arabella said. “If you have a secret, you must, of course, keep it to yourself.”

There was the sound of a door opening.

“What is going on in here? Who is talking?” a querulous voice asked.

Arabella got quickly to her feet. From the bedroom appeared a youngish woman wearing a negligee trimmed with lace. Her dark hair was curling over her shoulders and Arabella could see she was pretty in rather a coarse way.

“Oh, it’s you!” the woman said. “The child the doctor was telling me about. Well, I certainly didn’t expect you as early as this.”

“I am sorry to have come at an inconvenient hour,” Arabella apologised.

“I don’t suppose you could help it. So I shan’t blame you,” the governess replied. “Now, let me see, your name’s Arabella, isn’t it? Doctor Simpson did tell me.”

“Yes, that is right,” Arabella smiled.

“I’m Olive Harrison,” the governess said. “Miss Harrison to you, of course.”

“Yes, of course,” Arabella said respectfully.

The Governess went to the window and tugged back the curtains.

“I don’t have these pulled when the housemaid comes to make the fire,” she said. “All that rattle and jangle wakes me up. Now, I expect you would like some breakfast.”

“Thank you, but I am not hungry,” Arabella answered.

“If you aren’t, you ought to be,” Miss Harrison said. “You look as though a square meal would do you good! Never seen such a skinny little creature! But I remember, you’ve been ill, haven’t you.”

“Yes, I have had scarlet fever,” Arabella replied.

“Never mind, we’ll soon put a bit of flesh on you here. I will say one thing for this place, the food’s good. I’ve always said I would never stay anywhere where the food wasn’t.”

Miss Harrison finished pulling the curtains back from the four windows, then going to the fireplace, she tugged at the bell-pull.

Far away in the distance Arabella heard a faint sound.

“The housemaids will be waiting for that,” Miss Harrison said cheerily. “Someone will be along to dress Beulah, and they know I’ll be ready for my breakfast.”

She gave a large yawn as she spoke, making no effort to put her hand over her mouth.

Now that the daylight flooded into the room, Arabella could see how voluptuous the Governess was. Her négligée was strained over her full breasts, her skin white, her lips red and seductive. She had large blue eyes, fringed with dark lashes.

“Angels above! I’ve a head bursting at the sides!” Miss Harrison exclaimed.

She walked across the room, opened a cupboard and brought out a bottle. Pouring some of its contents into a glass she drank it quickly. Even before she smelt the spirits that seemed to pervade the room, Arabella knew what it was.

Brandy for breakfast! This was indeed a strange Governess!

“That’s better!” Miss Harrison said with satisfaction. “And now, dear, come and sit down by the fire and tell me all about yourself.”

Her tone was far more genial than it had been before. As she settled herself in a big armchair, she put out her hand to gesture to Arabella that she should sit in the one opposite. But Arabella was staring at the fat, white hand and something that flashed on its little finger.

For a moment she was unable to move and could only stand there, staring. For on Miss Harrison’s hand was, unmistakably, a ring that had belonged to her mother.

Two

Arabella lay sleepless in a small four-poster bed with a frilled canopy. She was tired, but her brain kept turning over and over the events of the day, and after a time she gave up the pretence of trying to sleep. She had been exhausted by the time Miss Harrison had sent for a housemaid to put Beulah to bed, but now she felt wide awake.

“You had best run along too, little girl,” Miss Harrison had said, but Arabella had known it was not because the Governess thought of her as a child that she was so solicitous, but because she was planning to entertain the Head Housemaid – Miss Fellows. An unopened bottle of brandy had been taken from the cupboard and was set ready with two cut-crystal glasses on a table together with a pack of playing cards.

Arabella had not been in the castle for more than a few hours before she realised that Miss Harrison had taken upon herself the role of Mistress. The servants hurried to obey her commands, and Arabella noticed that a number of very elegant pieces of furniture had found their way to the schoolroom.

After luncheon at midday, Beulah was put to rest in her small bedroom, which led off the schoolroom, on the opposite side to a large room occupied by Miss Harrison. Beulah slept by herself, except for her kittens, which had a basket at the foot of the bed.

“She won’t be separated from them,” Miss Harrison explained lazily, when Beulah cried for her pets and Arabella asked if she was to collect them. It was obvious that Miss Harrison was prepared to take the line of least resistance where her charge was concerned. Anything was allowed so long as it did not interfere with her own comfort.

It was not difficult for Arabella to understand Doctor Simpson’s anxiety that Beulah should have someone to play with, and if possible to instruct her. Miss Harrison did neither. She never spoke to the child except to tell her to come to the table or go to bed, and she seemed completely indifferent as to what Beulah did with her time or whether anyone or anything contributed to her happiness.