Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: Damascus Station

- Sprache: Englisch

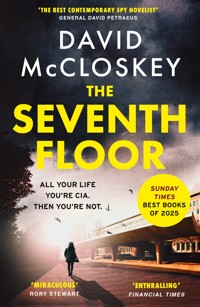

THE SUNDAY TIMES BESTSELLER THE TIMES BOOKS TO LOOK OUT FOR IN 2025 'A rare combination of experience and talent' Mick Herron 'His best yet ... Superb, addictively suspenseful, its politics and tradecraft coolly accurate, scary, intricate and complex ... The newmaestro of espionage thrillers'Simon Sebag Montefiore 'The Seventh Floor is a truly creative, riveting page turner that will cement McCloskey's reputation as the best contemporary spy novelist' General David Petraeus, former Director of the CIA 'This enthralling read cements McCloskey's place in the first division of spy writers' Financial Times THE THIRD NOVEL FROM FORMER CIA OFFICER, THE REST IS CLASSIFIED PODCAST CO-HOST AND THE BESTSELLING AUTHOR OF ***THE TIMES THRILLER OF THE YEAR***DAMASCUS STATION ('One of the best spy thrillers in years' THE TIMES) AND ***SUNDAY TIMES BOOK OF THE YEAR*** MOSCOW X FOURTH NOVEL THE PERSIAN AVAILABLE NOW TO PRE-ORDER ALL YOUR LIFE YOU'RE CIA. THEN YOU'RE NOT. A Russian arrives in Singapore with a secret to sell. When the Russian is killed and Sam Joseph, the CIA officer dispatched for the meet, goes missing, Artemis Procter is made a scapegoat and run out of the service. Traded back in a spy swap, Sam appears at Procter's central Florida doorstep months later with an explosive secret: there is a Russian mole hidden deep within the upper reaches of CIA. As Procter and Sam investigate, they arrive at a shortlist of suspects made up of both Procter's closest friends and fiercest enemies. The hunt soon requires Procter to dredge up her own checkered past in service of CIA, placing her and Sam into the sights of a savvy Russian spymaster who will protect Moscow's mole in Langley at all costs, even if it means wreaking bloody havoc across the United States. Bouncing between the corridors of Langley and the Kremlin, the thrilling new novel by David McCloskey explores the nature of friendship in a faithless business, and what it means to love a place that does not love you back.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 590

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THESEVENTHFLOOR

Also by David McCloskey

Moscow X

Damascus Station

SWIFT PRESS

First published in Great Britain by Swift Press 2025

First published in the United States of America by W.W. Norton & Company 2024

Copyright © David McCloskey 2024

The right of David McCloskey to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9781800753983

TPB ISBN: 9781800754539

eISBN: 9781800753990

Again for Abby, my love And for Miles, Leo, and Mabel

The building doesn’t love you back.

—CIA proverb

PART I

BREACH

1

MOSCOW PRESENT DAY

The Russian’s suicide pen, a Montblanc, was upstairs. Should have kept it down here, he scolded himself, even with Alyona around. If he was right about these cars, there was precious little time. He slid shut the drawer on his office desk and gently tipped Alyona from his knee.

“Up,” she insisted. “Up, up, up.”

Her hands were extended, fingers flapping into palms, but he was distracted by the monitors. Alyona mashed her face into his thigh with a squeal, imprinting his pant leg with sticky red stains. He looked down in panic, only to realize the stains were strawberry jam, which he himself had slathered on her breakfast toast. Normally this would have made him furious. Not now. He tickled her belly, and she laughed so hard she curled up around his feet in giggles. “Go find your mother, my sweet,” he said warmly, yet with firm undertones Alyona could not miss. The toddler scampered off, running too fast, as always, nearly catching her head on the doorframe on the way out. He heard her dash out toward the kitchen, where a teakettle had begun whistling.

Back to the camera feeds: The two black cars had come to a stop in the drive. No government plates, but he knew. On the lead car he saw the telltale triangle of dirt smeared on the top right corner of the rear passenger window. The brushes at the Lubyanka’s motor pool car wash did not reach that spot.

The Russian did not once consider going with them; he’d made up his mind on the matter long ago. But why had they given him this choice? They should have a rope in my mouth by now, he thought. His arms should be pinned to his sides, shirt and pants off, rough hands searching the lapel and pockets. And yet . . .

He stared at the jam Alyona had deposited on his pants leg. He dredged his finger through it and brought a sickly sweet dollop to his tongue.

Ten a.m. A slow Saturday morning at his dacha. He’d missed his ritual morning walk because he and Vera had stayed up too late, drunk too much, and, consequently, slept too late. The men outside were growing impatient since he hadn’t come out, he sensed. They’d driven up to the house along the drive tracing his normal path into the woods, their cigarette smoke seeping through cracked-open windows. For a few seconds the Russian watched the cars idling outside, trying to read the energy. And what he felt, he did not like.

“Vera,” he called. “I have visitors. Take Alyona into the garden to pick strawberries. We might have some with lunch.”

Vera appeared in the office doorway, her gaze settling immediately on the screens. “Is this about Athens?” she said, an edge in her voice, as Alyona tumbled in behind her. “Because it would be decent of them to finally explain why they asked you to come home so quickly.”

“I don’t know. Take Alyona outside,” he commanded.

“We’d just had Alyona all set in her school, and—”

“Outside,” he snapped. On the screens, five men had emerged from the cars. She looked at him worriedly. With a small sigh, he stood up and shooed her out with a peck on the cheek, whispering, “I’ll come get you when they’re gone.” Then he picked up Alyona and swung her around and buried his face in her sweet hair, all thick and lustrous again after the treatments, and he remembered why he had done what he had done. He took one more long sniff and kissed her head. He had no regrets. He’d make the trade again. He’d make the trade a thousand times.

He set her down. “I love you, my klubnichka,” he said.

“I’m not a strawberry, Papa!” She giggled, wagging her finger at him with a riotous smile.

Alyona followed her mother through the kitchen and outside into the garden. His lip quivered at the slam of the door. Alyona could not shut doors any other way.

The first knocks hit the front door. He flung open the lower drawer of the office desk. Ripping out the false bottom, he found the large envelope stuffed with smaller ones. One envelope held a letter for Vera. It was a formality, loveless, but kind, even generous, he’d like to think. Twenty envelopes were addressed to Alyona, bound together with a rubber band and labeled with a note bearing the following instructions: She is to open one on each birthday from her fourth through her eighteenth, and then when she turns twenty, thirty, forty, fifty, and sixty. Another envelope bore the name of his grown son and contained a letter written with as much love as his disappointment could manage. Hidden inside the folds of that letter was another, smaller envelope addressed to an apartment in Athens and affixed with an abundance of postage. Please drop the other letter in the mail for me, he had scrawled in a postscript to his son.

The knocks, which had grown louder as he reviewed the letters, now stopped. On the monitors he saw one of the men start working on the lock.

In the bathroom, the Russian jimmied the collection into Vera’s makeup bag. In his panic he worried the letters would be discovered in the inevitable and painstaking search to come. Why had he not seen to sewing them into Alyona’s clothing—perhaps a jacket—as he knew he should? But time was up: the front door squeaked open as he huffed upstairs to the spare bedroom. He sat at the old dusty desk, listened to the footfalls in the foyer, the hushed murmurs, the sounds of men padding up the stairs. For a fluttering moment he wondered how he’d been made. He could not know. He doubted the Americans ever would.

The Russian threw open the desk drawer. Picked up the Montblanc. “My daughter is here, you animals,” he bellowed in the direction of the stairs. “For god’s sake.”

A young heavy, his hair shaved close on the sides like a punk idiot, burst into the room. A second man followed close behind. Their eyes widened at the sight of the pen.

“Shame on you boys,” he said. Slipping the pen into his mouth, the Russian bit down into the barrel, sinking his teeth into the cyanide capsule snuggled inside. He heard Jack’s words, from long-ago Bogota: Three breaths, my friend, cup your hands over your face.

He did, taking the air in gulps: One, two. On the third they were over the desk and on him, crashing into the wall, cursing, shouting, grasping. Rolling him over, one of the men unfastened the Montblanc from his mouth. The Russian was already dead.

2

SINGAPORE

In the moment, Sam Joseph did not dwell on the awful significance of Golikov’s words, the blood that was sure to be spilled, the lives that would soon be wrecked on their account. That was all for later.

He first had to memorize them. And his recall had to be perfect, precisely as the message had crossed Golikov’s lips. Sam was using his childhood bedroom as a memory palace, stashing each word, in order, into different colorful storage bins, the ones under the bed where he’d kept the Lego. But to commit the message to memory, he had to be certain he’d heard it. And even though Golikov was seated next to him at the baccarat table, he was having one hell of a time with that.

The two subminiature strontium-powered mics had—shocker—performed beautifully at Langley, only to malfunction upon arrival in Singapore. So he had no backup. The analyst’s profile on Golikov had indicated that he spoke English fluently. Not true. He’d been forced into a meet on a casino floor, the type of camera-clotted surveillance environment that was precisely the opposite of where you’d like to meet a Russian. And the casino floor plans used to choreograph this bren—a brief encounter—had specified that the high-limit baccarat rooms were tucked well off the casino floor, and were therefore, in the estimation of the cable he’d written, all but certain to be appropriately quiet. Also false. Wildly, maddeningly false. A bank of high-limit slots just off the bacc room was jangling with the subtlety of a suit of armor pitched down the stairs. And it was Friday, two a.m., at the Sands: the tables were cheek to cheek. This was the emulsifying, brain-swirling din favored by the casinos, and, because he considered casinos to be something of a second home, by Sam Joseph himself. At least when he was gaming on his own dime. But now the racket was endangering his op, to say nothing of the cameras, and there was precious little margin to exploit.

He asked Golikov to say it once more. This time the Russian’s tone was still abraded with the texture of sandpaper and broken glass, but the gruff English had thankfully slowed to an annoyed crawl. Sam smiled, as if the Russian had shared a joke, and then leaned away from Golikov to bank the message while examining his cards. He had ten thousand dollars of taxpayer money in the pot. On this matter, the warnings from DO Finance had been stern, if ultimately toothless: He was required to pay attention, and instructed to lose as little money as possible. Under the lip of the table, Sam’s left hand placed his key card, labeled with his room number, in the Russian’s lap. At the same moment his right hand tossed his cards to the dealer and he whispered: “Two hours.”

He wouldn’t have executed the pass if he’d thought he’d been made; but for a flickering moment, as the Russian deposited the card in his pocket, uncertainty overtook Sam, and he wondered if someone was watching.

Golikov bet player on the hand, and lost. He bent his cards and flung them across the felt lawn of the table and tossed back two healthy fingers of scotch. “Enough,” he said, his hand slicing the air. “Done.”

He tipped the dealer, patted his hands on the table, and stood. With friendly nods and good-luck wishes to Sam and the other players, he stalked off. Sam caught Golikov’s eyes bouncing around the room. Appropriately afraid, Sam thought. Mark in his favor. Only the worst mental cases—the sociopaths and megalomaniacs—didn’t sweat the treason.

Baccarat was not Sam’s game: it was all superstition, no skill. He’d already lost fifty thousand dollars of U.S. taxpayer money in sixteen minutes. The next few hands would put his remaining twenty thousand in play. In that instant, he was far more concerned with the Finance paperwork than he was with the implications of what Boris Golikov had just shared.

Over the next ten minutes Sam worked himself back up the hole: down a mere thirty thousand dollars. Then, with a stingy tip to the dealer, one he could justify operationally to the nags in Finance, he took his leave. He exited the high-limit room onto the main casino floor, an expansive atrium swelling with tables overhung by soaring gold sculptures, and humming with energy.

Sam scanned for obvious heavies or any compatriots from the Russian’s trade delegation, but it was so damn busy it was impossible to know if the opposition had him or Golikov made. And he didn’t think there was a way to change that. He bought a coffee and strolled through the casino. He made a few stops: bathroom, blackjack table for a few hands, one of the bars.

Nothing amiss—he was feeling good, despite what the Russian had told him. That still hadn’t sunk in, and, further, Sam was operational, ticking through a tightly scripted plan built with two goals in mind: Protect the agent, and collect the intel. Analyzing the intel was someone else’s job, and his mind was already overcrowded, running hot. There was space only for the air pressure of the moment, and what it meant for the weather of the op. Gin and tonic in hand—untouched—he went upstairs to his room, where he pitched the drink into the sink. The room service tray went into the hall; do not disturb sign on the knob; a napkin tucked under the door. In the brief seconds of indirect discussion they’d managed at the tables, Sam had proposed this as the safety signal. All clear. He shut the door, careful to keep the napkin in place, peeking out.

From a compartment hidden in the side of his suitcase, he removed a thin pouch lined with a material that resembled aluminum foil. Unzipping it, he thumbed the cash and set the pouch on the cabinet near the television. One hundred thousand dollars: the down payment authorized if the Russian’s information was gold. Wellspring of another war with Finance. On the coffee table he arranged a bottle of Russian Standard, two glasses, and a spread: olives, nuts, chips, popcorn. He tossed the pens and notebooks into the desk drawer. No notes during the session, CIA had decided. Might put Golikov over the edge. And if the Russian’s trying to sell us what I suspect, the Chief had said, guy’s gonna be pretty spooked already.

Sam settled in to wait, and he was bad at waiting. He knew it, and so had the Performance Review Board, though they’d written it up using slightly different words (struggles with impulse control). His foot was tapping the carpet at a solid clip. He had nearly picked the popcorn bowl clean, then he had finished it, setting the bowl in the closet, out of sight, to avoid the appearance that he’d started the meal before his guest. He took up a sentry position at the desk, where the food was well out of reach.

An hour later Sam stood upright at the click of the key card and the clack of the handle. Two men he did not recognize entered the room. They wore suits. Their eyes darted around, searching for threats: other people, weapons, items he might turn into weapons. They moved fluidly, like men who entered other people’s rooms with some regularity. Sam had edged back toward the desk, with its lampstand made of marble.

“Get out of my room,” Sam said, with another half step toward the lamp.

“You are Samuel Joseph,” the blond-haired one said in heavily accented English.

Not a question. But it answered Sam’s: They were Russians. He considered which man to start with. Both were about the same height and build. He scanned both sets of eyes, looking for weakness, and decided: the one with dark hair.

But the dark-haired man drew a pistol fitted with a suppressor and pointed it at Sam. “You move, I kill you. I no hesitate. Sit down, Samuel Joseph.”

Sam did, heart in his throat. They had doubtless used the room key he’d passed the Russian at the table. If they’d made Golikov, what did they need with him?

“Much vodka for one,” said the blond-haired guy, lifting the full bottle of Standard to nail the point. “For one American, I think too much.” He eased into the chair across from Sam. Still standing, the darkhaired guy moved behind him. He heard the zipper of his suitcase. The heaping of clothes and shoes across the floor.

“Drinking problem,” Sam said, twisting his neck for a look at what the guy was doing. He was greeted by the unfriendly end of the darkhaired guy’s pistol, which jerked: Turn around.

The blond-haired guy snapped his fingers. “You look here. Otherwise, mess you up.”

“I think you’re in the wrong room,” Sam said.

“Why you talk to Boris Golikov?” The second whir of a zipper meant the one with dark hair had found the money pouch. Sam watched Blondie’s eyes widen slightly, then his hand beckoned for the cash, which he flopped on the table. “This for Boris?”

“This is a casino,” Sam said. “It’s for gambling. And who the hell is Boris?”

“What Boris say to you at tables?”

“Who is Boris?” Sam said.

“Look, we not patient guys,” Blondie said. “You see us, you know. You work for CIA. Also we know this. And we know Boris wanna hava chat. Now, you sit by Boris tonight. We see this. And here’s thing. We gotta know what he say. Gotta know. You tell us what he say, tell us full, and we walk out, clean and dandy.” Here, hands were wiped together for emphasis. “But you play dumbass and we got some problems. Okay?”

“Boris is the Russian who was at my table?” Sam asked. “Guy who got cleaned out, that right? I’ve got no idea why you’re in my room or who he is. Now get out.”

“Samuel Joseph, now, don’t play dumbass. Tell us now what Boris say to you.”

“I don’t know your Boris,” Sam said.

Blondie glanced right through him, at his partner, and Sam knew the look—he’d seen it on agents, on security investigators, on players across a poker table. A man who’d made a call. Blondie picked up one of the snack bowls, lofting it toward the ceiling.

Humans tend to keep an eye on objects thrown into the air.

Watching the nuts spill across the floor as if in a trance, Sam sensed a flash of movement behind him. Felt a prick in his shoulder. Heat flooded his body and limbs. When the warmth reached his brain, his head began to feel quite heavy, as if his neck were unsuitable for support. Then Sam was slumping forward, crashing into the bottle of vodka.

3

LANGLEY, VIRGINIA

Artemis Aphrodite Procter was squinting into the reflection of the rising sun shimmering orange across the surface of her beer. She slapped her card onto the bar with instructions to keep the tab open, collected her glass, and eased into her usual booth to wait for Theo. Procter was a regular at the Vienna Inn, but she was typically a night owl, and though she was also a well-known reprobate, this was her first time ordering booze during the breakfast rush, hand to God. Half the glass went down in the first gulp, the remainder at the jangle of Theo Monk pushing open the door. When her old friend reached the table, she hoisted her empty with a shake. “My tab’s open.”

Theo squinted into the glass and sniffed it with a wry smile. Returning with two, he wheezed into the booth, sliding one across to Procter. He thumbed the fabric on her rumpled tweed blazer, which she’d been wearing yesterday. “Walk of shame?”

“I wish. Left the office an hour ago.”

Regarding the sunrise beers with disapproval, a waiter unknown to Procter deposited menus on the table. Without picking one up, Theo ordered toast, bacon, and eggs over easy. “I’m drinking my breakfast,” Procter said, and shoved the menus to the table’s edge.

“Still no word from Singapore?” Theo asked, after the waiter was out of earshot.

“Radio silence. Station’s working their stringers at the Sands.”

“Plenty of explanations.”

“All bad.”

Theo’s silence signaled his agreement. He turned his gaze out the window and put back a good deal of his beer. She’d been drinking with Theo on and off and all around the world for about a quarter century. Drink made him a chameleon: chatty or silent, morose or joyful, kind or cruel—he might assume any combination or measure, and occasionally an anarchic blend of them all, during the same drinking session. The silence had become more pronounced in recent years. Their friendship extended back to their Farm days, and over twenty-five years they’d said most that needed saying—and an awful lot that didn’t.

Theo’s food arrived. He was dredging the bacon through runny yolks when Procter—empty in hand—stood, took two steps toward the bar, and stopped. She set down the glass and called for a coffee.

“Probably wise,” Theo said, when she’d slid back into the booth, “not to be soused during your first briefing with the brand-spanking-new Director Finn Gosford and his Deputy Director for Operations, Deborah Sweet.”

“I don’t know, Theo,” Procter said. “If I’m sober I might just tell the DDO how I feel, which is that it’s un-fucking-believable, those two running the place. And what a hell of a first Russia briefing. I mean, they’ve been on the job, what, a week? A single week, and we’ve already got a dumpster fire.”

“Doesn’t take long to torch a dumpster, Artemis, you know that,” he said, idly considering the blackened piece of bacon he was sluicing through the eggs.

“When was the last time you talked to either of them, anyway?” she asked.

He wiped a spot of yolk from the corner of his mouth and looked off into the middle distance, thinking about that. “Maybe six months after Afghanistan. Finn was a certified hero, of course. World was his.”

“Hero,” she muttered. “Fuck me.”

“I’ve offered.”

“You’ve tried,” she snorted. “There’s a difference.” She looked longingly into her empty glass. “Last meaningful thing I said to either of them would’ve been just after Afghanistan, at the hospital in Landstuhl, when we were laid up. I didn’t go to either retirement party.”

“You weren’t invited,” Theo said, exacting his revenge. “There’s a difference.”

“Were you?”

“Of course not.”

Procter sipped her coffee, while Theo put his toast to work as an egg mop. “Maybe Sam’s on a bender,” he offered, crust dangling from his lips. “Car accident. Ran off with a whore with a heart of gold. Stole the cash for his reptile fund. Coked up.”

“You don’t know Sam, and you’re also a dumbass. He’s lying low, dead, or being held by Russians. Odds on lying low drop with each passing hour.”

Theo took another bite of toast, changing the subject with a grimace and a nod. “Did the new occupants of the Seventh Floor get a brief on the Singapore op this week?” he asked. “It’s been so busy I can’t even remember if it was covered when they were up in New York.”

“They got the gist of it. Maybe not all the details.”

“Well, I’m sure they’ll be understanding,” Theo said, a smile beginning to crease his lips. “After all, Finn and Debs are our old chums.”

For the first time in nearly two days, Procter cracked a weak smile. Theo slapped his napkin onto his cleaned plate. “Let’s go. We should sync up with Mac and Gus before we jump into this meat grinder.”

When they entered his fourth-floor office, Mac Mason, the Chief of Operations in Russia House, was in the intelligence officer’s most natural position: hunched over a computer, reading the cable traffic.

Mac had tan skin and big friendly ears and hair that’d been gray as long as they’d known him. Which was as long as Procter and Theo had known each other. He’d also been in their class at the Farm, and then in Afghanistan they’d killed and nearly gotten killed together. When he swiveled around in his chair she could see that he’d been sorely tempted to put his fist through the computer screen. Unlike Procter, Mac had apparently gone home for a few hours last night. She could tell because his white shirt was starchy even if his eyes betrayed his exhaustion.

Procter and Theo took up around his table, but Mac just stayed put, glancing, in a perturbed silence, between the computer and a painting of a prowling wolf on his wall.

“What’s up?” Procter finally said.

At that moment, Gus Raptis, fresh from a cut-short tour as Chief of Station in Moscow, and another comrade from their Farm class, walked into the office. “You reading this?” he asked Mac, the tunnel of his stress apparently so dim that he did not acknowledge Procter or Theo.

“Goddamn mayhem,” Mac growled.

“What the hell is going on?” Procter finally barked.

Gus turned to her, his face lit by confusion veering toward rage: “BUCCANEER is dead, that’s what. Scrap of SIGINT in overnight. A fragment, admittedly, but we picked up a Kremlin flunkie telling a buddy that an SVR officer recently home from Athens killed himself during his arrest.”

“In the intercept,” Mac said, swiveling to his computer to read the cable, “the flunkie says rumors were floating around that BUCCANEER had been brought home on suspicion of espionage.”

Raptis shucked his glasses to the table. “Shit,” he said. “Shit.”

And that was deeply unsettling to Procter because this was only the third occasion in nearly as many decades that she’d heard Gus Raptis curse, and she remembered them all: in Afghanistan, bullet in his shoulder; in Georgetown, maybe fifteen years earlier, when he slipped on the ice last time they managed to get him drunk; and now, in Russia House’s quiet recycled air, contemplating the disaster unfolding before the Bratva.

Bratva: their foursome’s collective moniker inside CIA. The Russia House Mafia. Mac Mason, Chief of Operations; Theo Monk, Counterintelligence; Gus Raptis, now shuttered in a Langley holding position but until recently running the fieldwork in Moscow. And finally Procter, in Moscow X—overlord of the dirty, glorious covert action programs targeting Putin and his cronies. The Bratva’s paths had zigged and zagged in the years since the Farm. Somehow they’d managed to mostly stay friends.

“Still no word from Singapore?” Procter asked.

Mac shook his head. “Station thinks the Sings will cough up the casino surveillance footage, but it may take some time. Otherwise, silence.” He had joined them at the table, spreading across the chipped faux-wood surface the anodyne talking points they’d all prepared late last night for their meeting with the Director today. Mac clicked open a red pen and began to slash at the text. “Look, guys, in one hour we’ve got the first official Seventh Floor Russia briefing for”—he hawked something up his throat, anticipating the names—“our old friends Director Finn Gosford and his Deputy Director for Operations Deborah Sweet.” Mac delivered the titles in a sarcastic singsong lilt. He swiveled over to his trash can and spat. “And, lucky us, we come bearing nothing but problems. A busted bren in Singapore, a missing case officer, and one dead asset in Moscow.”

“They are going to flay us for all of it,” Gus said.

“They’ll flay us for just being here,” said Theo.

“It’ll be hard to pick just one grievance,” Procter agreed. “There are so goddamn many.”

4

LANGLEY

The reunion, in truth a bureaucratic spanking disguised as an innocuous-sounding briefing (“Director’s Special Update—Russia”) commenced promptly at nine. The war party was thinner than the typical Russia briefings because Gosford’s Chief of Staff had said he wanted only the four of them, leave the little people behind, please. Procter, Mac, Gus, and Theo wandered into the Seventh Floor anteroom outside the Director’s office. The room, watched over by agents of the DPS, the Director’s Protective Staff. The sitting area guarded the main hallway, cutting through the Director’s suite; the furniture was new, fruits of a recent renovation, and unlike most waiting rooms at CIA, the newspapers and magazines, to Procter’s great astonishment, were current.

Still, it felt alien to Proctor because it was now Finn Gosford’s waiting room. It was his office on Langley’s Seventh Floor. If you’d traveled back in time, Procter thought, and told me we’d be here waiting for Finn, I’d have said it’d be more likely that one morning I wake up with my face stapled to the carpet. Given her line of work, though, that was not impossible to imagine. No, it would have been more likely that she would occupy this Seventh Floor office—and hell would have to grow glaciers for anyone to give her the Director’s chair.

At the moment she couldn’t find a place to sit. The first week of any Director’s tenure is jam-packed with background briefings, so Procter and her friends found the room and adjoining hallway gobbed with analysts. With nowhere to sit, they stood along a wall until, after twenty minutes, a group from the Near East Mission Center shuffled out of the conference room, looking shell-shocked, as if a bomb had detonated in the middle of the briefing, or, as Theo would later quip, the Director had dropped his pants. Gosford and Debs crossed the hallway from the conference room into the Director’s office. “We’ll do the next one in here,” Finn called out to one of the Special Assistants.

And with that, Procter and her friends were told to go right on in, leaving the room full of nervous analysts, whose fidgeting and tapping and murmuring recalled the rising comprehension of steers on their way to slaughter.

Procter was often an unwelcome presence in a room. The feeling was a familiar one, but she could not remember it striking with such muscle. There were no smiles, the eye contact was reluctant drifting toward evasive, and the handshakes were stiff—not a blessed hug for an old comrade?—and fish-cold, as if Procter had shit smeared across her palms or was playing host to a fungus visible from some distance away. Greetings delivered, with everyone already exhausted, the Bratva took seats in front of Gosford and Sweet. Or, as Procter had known them back in the day, Finn and Debs.

Both of them looked pretty much the same, Procter thought. They looked good, and that was disappointing. Finn and Debs were the type of cherished enemies that you hoped, a decade on, would have slabbed on a great deal of weight, or lost their hair, or maybe a limb, to diabetes or gout or the vagaries of some exotic and excruciating infection. You wanted to stumble upon this type of rival at a reunion and find them careening downward—perhaps with a night’s distance to rock-bottom, so you’d have the pleasure of watching.

But looking closer, Procter saw it was even worse. Both seemed somehow more tanned and less wrinkled. (Botox? Had to be, right?) The bags they’d once carried under their eyes had been deposited at the Bratva’s side of the table. Gosford had kept his jet-black helmet of hair and Debs her frosty shoulder-length bob. The value of Gosford’s watch probably exceeded his new government salary. Debs—who was sporting a tight, suffragette-white dress that stopped short of mid-thigh and seemed to have a goddamn cape attached at the shoulders—looked tauter to Procter, as if in the intervening decade her old friend had finally declared victory over about fifteen pounds of midwestern chub. There were much deeper reasons to hate them, but these were all Procter required for right now.

And then Gus, well, poor Gus made the meeting’s first—but by no means only—mistake. “Finn,” he said, “welcome back and congratulations.”

“Director,” Gosford corrected, regarding Gus behind fingers steepled in the manner of a professorial douche. Procter felt Debs’s eyes boring through her. She looked up and tried to smile, and, to her surprise, Debs tried to smile back. But their bent lips were more grimace than smile, like two constipated folks in a face-off, and Procter eagerly surrendered when Gosford began speaking. “I know that we all have a shared history. But it is important that you treat me—and Deborah—as your superiors. I am the Director, and Deborah is the DDO, and it would convey crass cronyism if we did not maintain the professional hierarchy.”

No one nodded or offered any recognition of this statement. Procter had the feeling that if the offer had been put on the table, a couple of them might have quit on the spot.

“That being said,” Gosford said, breaking the silence to lean back and flap his tie, “this is . . . insane. Let’s admit it, shall we? Say it aloud. Insane. No other word. All of us together again. Small world, small world. Has it been since Afghanistan? It must be. Over a decade. My, my. Well, we’ll have time to catch up later”—Bullshit! Procter thought. And thank god for that—“but I’m afraid I’m back-to-back today. Now, to business.”

Mac and Gus led the charge, describing for Gosford and Debs the facts as they had them on the mysterious death in Moscow. When they were done, Procter would cover Singapore. “It’s your op, Artemis,” Gus had said, with the tone of a man flinging a hot potato. “You should take that one.” The briefing careened from stilted to bad to worse. Right around when Mac clarified a question from Debs about their certainty that BUCCANEER was actually dead—Pretty certain, ma’am, he’d said, belatedly choking out the ma’am part—Gosford flicked to angry, a pattern that mirrored some of his behavior when he’d run the Counter terrorism Center a decade prior. Then, he had claimed credit for operations in which he’d played a minor role, shoveled all problems to Debs, and occasionally lost his marbles on subordinates for slights, most of them minor, and quite a few of them—but not all—entirely imagined. Finn Gosford was a politician, a word that curdled in Procter’s ears like vile slander.

“Good grief,” Gosford said. “And how many assets are left?”

Mac turned his gaze to the ceiling, running the math. “Two more internal reporters, three outside, maybe a half dozen cases on ice, inactive for a year at least.”

“And this BUCCANEER had been our best?” Gosford said.

“Far and away,” Procter replied, and Gosford looked at her with shock for having taken the elaborate liberty of speaking. “Before they sent him to Athens he was our most senior asset inside SVR.”

“I remember that source from last week’s briefing documents,” Debs said, rifling through a stack of papers. “You know this Singapore business we’ll discuss in a moment recalls what REMORA told us not three days ago. Does it not?”

“Stop you right there,” Gosford barked. “Stop. Stop. Who is REMORA?” He fought, had always fought, to instantly moor conversations that were drifting beyond his reach. And he didn’t seem to much mind whether the boat capsized in the process.

“One of my cases,” Theo said, his face blanching. “A colonel, the Deputy Chief of the SVR’s Fifth Department. Their Europe guys.”

“We met him a few days ago,” Debs said, leafing through more of her papers. She flicked a pair of mustard-yellow frames over her face when she came to the one she sought. Licked her thumb and flipped a page. Her face was still buried in the report when she said, “REMORA offered vagaries about threats against Americans in Asia. It was not”—here Debs cleared her throat and tipped her head toward Gosford—“actionable.”

A look from Debs seemed to convince Gosford that here should end that line of inquiry, so he said: “I hear we have a problem in Singapore.”

Debs slid the glasses off her face and pointed them at Procter. “She’ll get you up to speed on that.”

And . . . I’m under the goddamn bus, Procter thought, looking up. About right. She started with a few minutes of setup, how a Kremlin insider by the name of Golikov had, through a cutout, passed a letter to Moscow Station. He was on an East Asian junket, a Russian trade delegation trawling through the region searching for partners willing to help them bust sanctions, and we know he’s a degenerate gambler, so—

“I’ve heard you sent a Headquarters-based officer,” Gosford cut in. “Why not use someone local?”

“I didn’t want to risk burning someone in the Station, nor did I want the Sings involved; they are leaky as shit, goodies tend to find their way to Beijing, and—”

“Instead you thought it was safer to use a disgraced officer to handle the bump,” Debs said. “One with a gambling problem. And, poof, he’s gone missing. Along with well over one hundred thousand dollars of taxpayer money, not to mention a head full of our deepest secrets.”

“Hey, now,” Procter said. “Hey, now. Sam is, or was, a professional poker player. Not a gambling addict. He had pristine cover for travel to Singapore and a plum reason to sidle up to Golikov at the tables. Which is what happened, then—”

Debs swung in again. “Did he defect? Is he on a bender? A gambling spree? What?”

Fact was, there was no use in arguing with them. Lordy, she knew they had their reasons, mostly Debs. Procter did deserve some hell for what she’d done to the poor woman in Afghanistan, but now the shoe was decidedly on the other foot, a foot now wearing a gigantic and doubtless quite fashionable jackboot, good for squishing and stomping. They hated her, pure and simple. And probably the others, too, though with far less zeal. Gosford and Debs were politicians and Procter was a politician’s nightmare: a competent extremist, inoculated against bullshit, unwilling to kowtow, even when it made damn good sense. The other three Bratva would lick some ass if required, and though her tastes were eclectic, she’d yet to work up the stomach for that. A lot of people hated Artemis Aphrodite Procter, and each, well, each she considered marks in her favor.

“He’s missing,” was all Procter offered. “Right now we don’t know anything else.”

Debs said: “Let’s recap, two options. One: you walked a disgraced, gambling-addicted officer into a Russian trap. Two: he’s absconded with a small fortune in taxpayer dollars, and is likely at the tables right now frittering it away.”

“The events in Moscow,” Mac said, “BUCCANEER’s death, would hint at the former. A trap.”

Heads poked up or turned as the door cracked open and a woman appeared. It was Petra Devine, chief of what was technically termed the Special Investigations Unit, but popularly known as the Dermatology Shop: CIA’s molehunters. As always and everywhere, an espionage outfit’s chief molehunter was an old woman. In this case, one in a shambolic floor-length dress topped by a weird gray vest, Coke-bottle glasses, a bird’s nest of curly gray hair, and jowls like a turkey wattle. Stone-cold church-lady vibes. Though in Petra’s case that wattle didn’t need to flap for too long before you knew that she wasn’t going to be tickling organ keys or running the fall potluck. The Chief Derm was typically a woman of unquestioned loyalty, decades of service, and zero political acumen. The Derms built elaborate matrices to track anomalies in the intelligence reporting, searching for a common denominator or hidden clue to a mysterious loss. Procter had seen Petra’s matrix: an elaborate map of a road to nowhere. Procter watched Debs’s lip curl as Petra shambled in and took a seat.

“I thought we took you off the invite list for this meeting,” Debs said.

The woman looked Debs over for a moment, then said dryly: “Oh? And why would you go and do that?”

Gosford shut one eye to stare at Petra, as if perhaps this were the sort of creature best seen through a scope—tele-, micro-, or rifle, take your pick—and Procter thought for a moment he was going to force an apology, as he had done to Gus at the meeting’s kickoff. Part of her hoped he would, because that would send the meeting nuclear, a real scene, and its mushroom cloud would tower over the spat between her and Debs. Instead, Gosford cracked open his other eye, blinked, and said: “She’s fine, Deborah.”

Petra mumbled something, smiling at her gigantic black shoes while she took the empty seat next to Procter. Procter caught a whiff of a singular smell carried from her clothes: dog dander.

“You were talking about traps,” Petra said. “And that’s probably what it is. Because it never goes like this, not naturally. Sure, the shit hits the fan in this business, well and truly and often. We all know it. But we have too many problems all at once. BUCCANEER is elaborately recalled from Athens, then drops dead a few days after his inglorious return to Russia. And the same day, your boy Sam”—she’d taken Procter’s shoulder into her badger grip—“goes AWOL in Singapore after a futile attempt to hear out a Russian with very important news for CIA. The business doesn’t work like this. And since you are all tap-dancing around the obvious, let me articulate it for you: we have a big problem.”

Amen, Procter thought.

“No one has any proof of that,” Debs snapped. “There are other explanations—a commo breach, tradecraft errors, dumb luck.”

Ignoring Debs, Gosford gave Petra an icy glare and said: “And what do you suggest we do about this problem?”

“Take a good hard look at things, sir”—honorific delivered like a kick in the shins. “Run a full and proper investigation to locate the breach.”

“You want a witch hunt? Show trials? Am I hearing this right?” Gosford said. He had his chin propped on his hand to stare at Petra. “Turn the place inside out during my first week on the job? On what basis? We all know how awful those get. There’ll be a panic, leaks, in the end we’ll probably find nothing. Just burn the place down to watch the fire.”

“Can’t know you’ll find nothing until you look,” Petra said. “And I’m telling you, I think we have a problem.”

“Oh lord,” Debs said, “enough of these dark fantasies.”

Gosford’s attention had wandered off. Checking the three-by-five card holding his daily schedule, he glowered, first at the card, then over to Procter. “We need to stop this meeting here,” he said. “Find the case officer. Keep the DDO’s office apprised of any updates. That is all. Dismissed.”

Procter had never been in a CIA meeting that concluded with a formal dismissal: she almost chalked up her second laugh of that grim morning.

They shuffled out of the office, probably with the same look as the group that preceded them, Procter thought, as if Gosford had dropped trow or ordered them up over the lip of a trench.

“Big problems,” Petra was muttering to Procter. “We’ve got a big fucking problem inside these walls.”

5

MOSCOW

Rem Zhomov had the phone in one hand and pills in the other. The bathroom sink was busy filling his glass. He listened to the report for a few moments until the voice on the other end, spooked by the silence, said, “Are you still there, Rem Mikhailovich?”

Rem shut off the water. “Yes. Go on.”

While he did, Rem—at this hour in his bathrobe—slapped the pills from his hand onto the countertop and sorted them into two piles: on the left, those that would make him drowsy; on the right, those that would not. To the left: the orange one for sleep, the yellow for his back, the fouls-melling brown one for his blood pressure. These were swept from the counter back into the plastic case with the compartments for each day of the week. Balancing the phone between the ear and the crick of his neck, he swallowed the pink stool softener for his hemorrhoids, the green for his arthritis, lighter green for his thyroid, and the sweet-smelling little red octagon for cholesterol. The colonel’s report had concluded by the stool softener: the line was silent save for Rem’s gurgles and swallows, concluding with the clink of his glass on marble.

“Have a driver outside my apartment in ten minutes.”

Rem hung up and went to the bedroom. Ninel, in bed, looked up from her book. “You are going out?”

“Yes.”

“You look cross.”

“I am.”

She clapped shut the book, flung off the bedcovers. “I will pick out a suit.”

He watched the dark city float by the windows of his car. The jet-black suit that Ninel had selected matched the night sky and the car’s paint and its leather. He was camouflaged: a faceless bureaucrat sliding into the Moscow night.

The suit was an older one, purchased in Rome when he’d been rezident there. Finely cut, it still clung nicely to his frame. Since that tour Rem had added cataracts, arthritis, and—thanks to his father—congenitally high blood pressure, but not a single pound. The car came to a stop under the light of a streetlamp. He caught sight of dust on his shoes and stooped down gingerly to wipe it away. Ninel had picked the shoes, too, but it had been ages since he’d worn them and she’d forgotten to polish them in the rush. It could not be helped. Ninel saw the big picture, Rem saw everything else.

And the only thing Rem could see now was the danger facing his top American asset, known inside the Forest as Dr. B; it was the reason the Director, the week prior, had permitted Rem to stay on beyond mandatory retirement.

Rem had read the ops note from that week’s meeting with Dr. B no fewer than ten times. He’d quizzed his handling officer on Dr. B’s body language, intonation, and facial grammar: each a plank in the emotional architecture of the SVR’s most valuable penetration of CIA—ever.

The summary: Dr. B was stressed and concerned, this was obvious even from the written ops note, but not panicked. Dr. B was too cool for that, though the asset was appropriately worried—as was Rem—that the week’s drama imperiled their shared mission. Rem did take some measure of pride that the chaos had not halted Dr. B’s production. He’d been able to share a stack of Dr. B’s reports with the Director just that morning, including a few CIA analytical pieces and minutes from the American National Security Council’s deliberations on Russia. The requested China haul, Dr. B promised, would come next, perhaps by autumn.

Tremendous risks had been taken that very week to protect Dr. B, and Rem feared—no, he knew—that many more would be necessary in the weeks and months to come. But that was for later. Tonight, Rem had work to do. He had a damage assessment to conduct. He had leaks to plug. Soon Moscow was an orange ribbon of light behind his car. Rem was glad he’d not taken the other pills; he was already so tired.

In happier times, Saint Catherine’s had been a convent. The nunnery was painted a sunflower-yellow that glowed eerily in the darkness. The buildings were fronted by rows of white columns. Rem had selected the convent because it required little of the mundane facilities work that typically accompanied the establishment of an informal prison. The most difficult part, in the end, had been relocating the nuns, who put up a more savage fight than he would have thought possible from a half dozen septuagenarians. In the end, the matter went to the Director, who called the chief of the Presidential Administration, who doubtless shook some cash at the Patriarch. The nuns were dispersed to a convent near Nizhny, and their old chapel became the holding chamber for a specially fitted box. The somber stone cellar was outfitted as an interrogation chamber. Though Rem did not like that word. These were merely conversations, he believed, even if the other person was occasionally upside down, hauled up by their arms until they lost consciousness, or locked for a spell in a dreamlike world of perpetual light and noise.

From Rem’s vantage, Samuel Joseph’s mouth was curled into a joyful smile, but that was merely a contortion: he was upside down, his feet were strung from the rafters. An interrogator stood beside him. For a moment Rem watched Samuel dangle from side to side, broom of hair gently sweeping the stone. The American had been spirited from Singapore on a ketamine-dribbled itinerary of vans, shipping containers, military transport planes, and helicopters. He’d been at Saint Catherine’s for all of two hours. Most of it upside down, shaking things loose to get him started.

“Bring him down,” Rem ordered the interrogator.

They sat at a wooden table spattered with oily stains. Here, he thought, the nuns must have prepared their food. Samuel sported a loose gray jumpsuit. His eyes were red-rimmed and hollow from the ketamine injections during transport, and his cheeks were flushed with blood from hanging upside down. Rem called for tea and they drank in silence. Samuel did not meet his eyes. When Rem had finished his tea, he spread his palms on the table and shifted his weight in the chair with a wince. Damn hemorrhoids.

“You met Boris Golikov in Singapore,” Rem said.

“I met a man named Boris. Briefly. At the tables. Small talk. I did not know his name until your men kidnapped me. This detention is illegal. This—”

Rem interrupted: “What did he tell you?”

“My detention here is illegal.”

“You’ve said that already. What did he tell you? What did he give you?”

“He asked me about my whisky.”

“What were you drinking?”

“A Macallan.”

“How old?”

“I don’t know.”

“What sort of man doesn’t know the age of his whisky?”

“Ten years.”

“What was Golikov drinking?”

“A Springbank. That’s what we were talking about. That’s all we talked about.”

“What did he pass you?”

“I told you. Nothing.”

“Why did you have one hundred thousand dollars in cash in your hotel room?”

“It’s a casino.”

“You did not wire money into an account at the casino?”

“I prefer cash. Feels real to me.”

“You are a CIA officer.”

“I am not. I am a Foreign Service officer.”

Rem laughed. “Ah. Yes. But you were on a tourist passport in Singapore.”

“As I’ve said, I was in Singapore to gamble. Not to work.”

“Long way to travel for cards. Las Vegas is, what, a three-hour flight from Washington?”

“I like to visit new places.”

Rem paused for a moment as he considered the man before him. “How is Artemis Aphrodite Procter doing these days?”

“Who?”

“You do not know her? What a shame,” Rem said. “She is a treat. A gem of your wretched Service.” Rem shifted forward in the chair. “I understand from our files that you were interrogated in Syria, however briefly. Now, we trained the Syrian security services, so perhaps you are thinking you will resist what we are going to put you through. But you cannot. And here is why: There is no clock. We can hold you forever. No one is coming. They do not know where you are, nor who took you. Oh, of course they suspect it, but they cannot prove it, and there is no trail leading from Singapore to Russia. So, we are going to hold you here, for however long it takes, until you give us what we want. You tell me why you were in Singapore and what Boris told you, and I will personally drive you to the U.S. Embassy. That can happen tonight. It can happen in this moment. You just have to tell me. We are not monsters. And you know how we operate. The spy flicks would have us Russians jerking out fingernails and electrocuting kidneys and balls and beating you senseless with leaden pipes and maybe putting a bullet in your neck for good measure. As though we were the American Mafia. And do you know what? After a few weeks of what we’re going to put you through, you’ll be begging me for the relatively clean experience of electrocution, or some light cutting. You will plead for a beating with a pipe. Because, unless you cooperate, you will travel into a darker and far more sinister forest. You will hear nothing, or it will be so loud you will hear nothing else. There will be no light, or so much of it you cannot see. You will be lonely, so alone, and when you are not you will wish you were. You will lose all sense of place and time and satisfaction and truth and beauty. You will beg for someone to cut you so you might feel something.” Rem stood and gripped the back of the chair. “So, that was a lot. And so very dark. Samuel, I am former First Chief Directorate. An artist, not a thug. I must say I don’t care for this piece of the work, but I have my reasons, distasteful though this all is. So: Out with it. Golikov. What did he tell you?”

“He told me he was drinking a Springbank.”

Rem looked up at the camera above the door. “We’re done for now. Put him in the box.”

Sam’s box was a frantically still world of blinding light and cloaking darkness, frozen silence and roaring noise. There were six lights set into the ceiling, behind thick plastic. Crackers, bread, and hunks of pickled fish arrived at random on a rubber plate, set on a rubber tray bearing a rubber cup filled with water. A rubber bucket toilet sat in one corner. It did not overflow and yet he could not recall anyone ever emptying it. He wore a gray jumpsuit with eighteen frayed threads coming off the pant legs. He’d counted them dozens of times.

Inside the box he could not quite fully stand. He could lie down, though. He could sit against a wall. His box was a square: Ten and a half steps, heel to toe, brought you from side to side. The sides wore a thick cloth fabric. There were no visible screws or rivets. When the lights were on, he could make out tiny red stars printed on the fabric.

Once, in the upper corner of the box to the right of the door, he’d spotted a fraying slice of fabric. When he’d pulled on it, the door opened and they told him to stop. He’d not spoken to a human in so long that he just kept on yanking—he was hoping for a fight, for a chat, for, as that old man had said, someone to make him feel something—and two men burst through the door. They jabbed his shoulder and when he woke up the fabric had been repaired. His memory, his existence, had been reduced to the box and that night in Singapore. He came to believe he’d had no life before this. CIA did not exist anymore. Neither did Procter. Neither did Natalie. Life was a busted op in Singapore and this cell, which he assumed was in Russia but of course could not know. Sometimes he wondered if his box was in a room down the hall at the Sands.

They knew who he was, of course. He’d crossed paths with the Russian services in Syria, years earlier, as the old man had said. They understood he was CIA. But to keep him like this? The only way out was to hold back the one thing they wanted. If he told them what Golikov had shared, they would never let him go. They might not anyhow, but once he’d told that old man what Golikov had said, they could never let him leave, not even in a box. The only way home was to hold it all deep inside.

When the crackers arrived, Sam would dip into the memory palace of his childhood bedroom, crouching to slide the colorful bins from beneath his bed, opening them to reveal Golikov’s words, each in its precise order, spoken in that brief moment at the table. He would silently speak the truth to the cracker. He would eat it, then he would begin counting the little red stars.

6

LANGLEY

The bureaucratic torture of Artemis Procter was excruciating and, until the very end, administered at a sensible arm’s length, to avoid the mess. The first prick of the knife was Procter’s formal elimination, no reason offered, from the Director’s Russia updates. The next was to slash her Moscow X crew to skeletons. Procter had a team of analysts and techies she’d corralled for special projects, and the Seventh Floor commandeered those, the anodyne email she received explaining that it was critical to centralize such Enterprise Resources inside the Directorate. On a Monday they all sat in the Moscow X spaces, by Tuesday lunch those bullpens and cubicles had been stripped down to the last stapler.

Procter wasn’t due for a polygraph for another year, but Security made her sit for one anyway, pairing it with a laborious background investigation that involved calling friends and relatives and neighbors. She had tried to keep a low profile; now she had government creeps slinking around the subdevelopment asking if Artemis Procter threw ragers or snorted coke on her back patio. The investigation didn’t worry her—she had nothing to hide—but she was wildly agitated, and that, well, that was precisely the point. By late spring, twenty-four Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) complaints had been called forth from the mists of her long career, all of them focused on what the Chief considered her idiosyncratic—and brutally effective—management style, which in the complaints was described as “conduct creating a work environment that is intimidating, hostile, or offensive to reasonable people.”

Procter had been up for promotion to the Senior Intelligence Service (SIS), but after the EEO complaints and the background investigation, her package was pulled from consideration. In a rather nasty gesture, the formal note explaining the panel’s decision referenced a Russian blackmail attempt from a few years back that had concluded with her unceremoniously assaulting the officer making the pitch, just after he’d shown her a bunch of nudie pics snapped while she’d been drugged. “Professional lapse,” was how the note described it, “one in a long string leading up to the present operational planning for Singapore.” Though as yet her old friend’s name and office were not associated with the torture, Procter saw the hand of Debs on all of it. Here, more than a decade on, was Deborah Sweet’s revenge.

Of all the indignities she suffered in those months, the violations of her office were perhaps the most galling. Her shoestring, gutted Moscow X shop was transferred to the Ground Floor—the basement—smack across the hall from the hot dog machine. Then, Security paid a surprise visit and wrote her up in violation of Agency Regulation 32-498 (Rules and processes regarding the possession and storage of weapons on Agency property). It’s just a baseball bat, she’d said to the guy, and look, it’s decorative. The truth was that the bat, signed by every member of the 1997 Cleveland Indians World Series team, had been used as a weapon, just not recently, nor inside Headquarters. “What do you have against Cleveland?” she asked, and never did get a response. The Security officers simply impounded the bat, and a citation went into Procter’s file, which was thickening rapidly during those bleak months.

The instruments of torture soon diversified, branching out from the Agency’s formal mechanisms to more unofficial forms of amusement. Each morning, when Procter flicked on the lights, she would find, primly stacked on her chair, forms advertising employment opportunities elsewhere: McDonald’s, Cici’s Pizza Buffet, a Northern Virginia–based proctology practice, all manner of strip clubs, Goldman Sachs, a Craigslist “Casual Encounters” post seeking a submissive, Bain & Company.