5,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

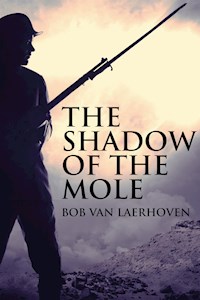

1916, Bois de Bolante, France. The battles in the trenches are raging fiercer than ever. In a deserted mineshaft, French sappeurs discover an unconscious man, and nickname him The Mole.

Claiming he has lost his memory, The Mole is convinced that he's dead, and that an Other has taken his place. The military brass considers him a deserter, but front physician and psychiatrist-in-training Michel Denis suspects that his patient's odd behavior is stemming from shellshock, and tries to save him from the firing squad.

The mystery deepens when The Mole begins to write a story in écriture automatique that takes place in Vienna, with Dr. Josef Breuer, Freud’s teacher, in the leading role. Traumatized by the recent loss of an arm, Denis becomes obsessed with him, and is prepared to do everything he can to unravel the patient's secret.

Set against the staggering backdrop of the First World War, The Shadow Of The Mole is a thrilling tableau of loss, frustration, anger, madness, secrets and budding love. The most urgent question in this extraordinary story is: when, how, and why reality shifts into delusion?

"The Flemish writer Bob Van Laerhoven writes in a fascinating and compelling way about a psychiatric investigation during WW1. The book offers superb insight into the horrors of war and the trail of human suffering that results from it"

- NBD Biblion

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

THE SHADOW OF THE MOLE

BOB VAN LAERHOVEN

Contents

Part I

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

The Mole’s Writings In The Grey Notebook I

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

The Mole’s Writings In The Grey Notebook Ii

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Part II

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

The Mole’s Writings In The Grey Notebook Iii

Part III

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

The Mole’s Writings In The Grey Notebook Iv

Part IV

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Part V

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Chapter 72

Chapter 73

Epilogue

You may also like

About the Author

Notes

Copyright (C) 2022 Bob Van Laerhoven

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2022 by Next Chapter

Published 2022 by Next Chapter

Edited by Lorna Read

Cover art by CoverMint

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author’s permission.

PartI

Prologue

Before they descended into what they called ‘Satan’s lair’,they murmured, with their heads bowed, a prayer to La Sainte Vierge1. Their voices were soft and solemn, like when they were children. In the shadows, their lanterns sparked the dust into a golden mist, as they hacked their way into the earth.

Jean Dumoulin used to hum softly but melodically during his work in the tunnels. His fellow diggers had nicknamed him ‘the canary’. Of late, he had taken to murmuring the bawdiest beer hall songs he knew, for the frankly insane reason that his regiment, the 13th French Infantry, had received the audacious orders to dig tunnels under the German tunnels at the spot that everybody in the Argonne-region called Fille Morte2.

That day, February 26,1916, Jean Dumoulin had turned to inventing his own songs. Faced with the threat of German tunnels above him, he sang only in his mind. Dumoulin liked to surprise himself with whatever words came to him. The words made him feel different: not a twenty-six-year-old French soldier clawing away in near darkness, but more like a classic Greek poet, posing with a lyre on a mountain top overlooking a shimmering sea.

Dumoulin was crooning Ma bouche sera un enfer de douceur/tu crias ton armée de douleur3, while he used his pick-axe to clear the rubble around the entrance of an old mine gallery they had discovered. He pondered which verse would come next: ton amour armé or ton amour blindé?4

It was then he saw the body lying in the gallery. From time to time, when they were grubbing in the earth, a shovel would uncover a half-buried body. They couldn’t always tell if the stiff was German or French. Often, all that was left was a rotten lump of meat. In spite of the stench and their revulsion, the sappers would try to identify it. Who else would do so? They thought of all the missing men and their anxious relatives and loved ones and they searched the body for anything that could lead to its identification.

“Nom de Dieu,” Dumoulin hissed over his shoulder to his companion Guillaume. “Another stiff. Hope this one doesn’t break in half like the other one.” Neither had actually seen the mummified corpse of a miner, perished years ago in the coal mines, who was said to have cracked in half when tunnel diggers brought it to the surface, but the story was legendary and if you denied it, you were just a cynic.

Cursing under his breath, Jean moved forward. When his hands touched the body, he jerked away as though someone had stabbed him.

ChapterOne

So softly treads the night.

Standing behind my right shoulder.

No breath reaches my skin.

ChapterTwo

The sky was the colour of straw, with a deep blueberry glow at the horizon. The Meurisson Valley, home to the field hospital which served the whole region, lay in Bois de Bolante, a low-lying part of the great Argonne woods. Dr Michel Denis walked there through the trenches. The recovery area was crudely constructed – a semi-underground complex harbouring medical provisions, ammunition and food storage, bathhouses and a sickbay. Like everyone else who worked there, Denis was curious about the infamous ‘Mole’, and he wanted a closer look. The sappers digging tunnels under the German lines had found the unconscious man, dressed in civvies, in the tunnel of an old charcoal burner. A day later, the man was still unconscious.

In the sickbay, Denis went to the patient’s bed and studied his facial features. Wide ears, a somewhat beaked nose and jowly cheeks, perhaps Semitic. Denis guessed The Mole’s age at about forty-five. Baggy blue skin under the eyes. As he made these observations, Denis came closer and now he stood at the bedside. Startled, he glanced at where his own right arm, severed by a piece of shrapnel, should have been. Involuntarily, he was reaching out with his phantom limb to touch the man’s left leg. All at once, a hail of shells passed over, as though the memory of that shrapnel had provoked the Germans at the north side of the Meurisson Valley. The shells drummed the basement walls with their deafening low thunder. Denis pictured the men in the icy trenches at the front, frantically seeking shelter. Since February 12th, after heavy snowfall, a light thaw had set in. It drenched the trenches with cold, gurgling mud, and inundated the mine corridors, used to infiltrate enemy territory, with melted ice: sluggish, foul-reeking, and copper-coloured.

An explosion shook the basement. Denis looked around him. Rumour had it that the Germans, being technically advanced, had electric lighting in their shelters. The French hospital had to make do with candle lanterns. As a result, bizarre shadows waved on the walls in a slow, undulating rhythm. No wonder the wounded called the hospital le pot de chambre de la France. At the moment, the chamber pot of France was a dazzling phantasmagoria of shapes chasing each other on the walls and the floor. Light and darkness played on The Mole’s face.

In the shadows, the man opened his eyes.

ChapterThree

Captain Réviron, a thin, wiry man with close-cropped wavy hair and rotten teeth, was middle-aged and bone-tired. Nevertheless, his slicked-up hair seemed to have been parted down the middle of his skull with a razor. His face betrayed a heroic tiredness, highlighted by the feeble lanterns in the damp-smelling, propped-up cave that was supposed to be his command-post. He sat before a crude table made from logs scavenged out of the woods, littered with documents and maps. Denis felt his gaze like the eyes of a suspicious dog.

“Lieutenant Denis,” the Captain said. “If this so-called Mole of yours has deserted from the ranks, he’ll get court-martialled. I imagine your Mister No Memory will recall his name, rank and number pretty sharp once he’s looking into a row of black muzzles. But that’s for after the changing of the troops – when we can send you both back behind the lines. Till then, make it your business to find out who he is.”

Denis should have been repatriated ten days ago when he had recovered sufficiently from the amputation of his arm, but the bad weather and the Germans’ relentless offensive had made that impossible.

“With all due respect, Captain, I don’t think the man is faking. His behaviour is so aberrant that…”

Réviron shot Denis another dubious look.

Denis wanted to scratch his ear, remembered that his arm was gone and reached over to rub the lobe with his other arm. “Let’s say peculiar at least, if you don’t like the term aberrant.”

“There are rumours, Denis.”

“I’ve heard them, Captain.”

“I heard the men prattle that he’s some goddamn ghost. The Garibaldiens are fighting on our side but they are a superstitious lot and could turn against us if we don’t quell these rumours. I don’t want any of that fluff in my regiment.”

“I understand, Captain. But there will always be rumours amongst the men. These dismal woods, these gruesome circumstances – it sets off their fantasies: evil spirits, the devil, all manner of chimeras… Mind you, I don’t suffer such affliction and personally I regard The Mole as a patient, not as Satan in person.” A pinch of irony was not absent in the young doctor. “My diagnosis is that the patient is genuinely suffering from shell shock and has really lost his memory, maybe even his mind. Moreover, I think he’s a civilian. He wasn’t wearing any military tag. Since he was on foot, we may assume he’s from this region. I examined his hands. Those are not the hands of a soldier or a farmer.”

“That’s no proof at all. Recently, they’ve drafted everyone who can carry…” Réviron shot a glance at Michel’s stump and waved dismissively, in an almost feminine gesture.

“Yes, but no man can be on the frontline for weeks or months without traces of gunpowder on his hands.”

“Denis, I am truly sorry for what has happened to you and I understand that for a young man, it must be tough to lose an arm. But your theories about ‘front line traumas’ are a threat to discipline in the ranks. A true soldier has no traumas. Bring that man’s memory back – use all means necessary, by Jove – and we’ll see if it’s a trauma or the booze that made him burrow in a deserted mine tunnel.”

Back on the surface, a row of sharpened branches had been driven into the muddy ground, with the cadavers of at least fifty rats strung up by their tails between them. Denis walked along the line, smiling and nodding to the grinning group of soldiers who invited him to a “rat bouillabaise”. After such a brew, he assured them, their breath would be foul enough to take out any German soldier within ten meters.

Soon, we’ll all be like those rats, Denis thought. Bloodless corpses strung up on barbed wire. Denis had been a psychiatrist in training when the war started. He had learned to be attentive to the difference between what his professor had called the ‘projected self’ and the ‘inner self’. When inwardly he was sombre, he tended to crack jokes.

The distant booming of war began again, like a thunderstorm gathering strength, coming closer, fast.

War’s having fun, Denis thought, with a sudden sense of unreality.

ChapterFour

In Denis’s ears, the war-sounds outside the field hospital were a mixture of screeching, beseeching, wailing, and hailing.

The war-victims presented a dizzying array of bloody limbs and faces: some of the eyes without a trace of hope, others clenched tight, tears here and there painting grimy patterns on twitching jowls.

The stretcher bearers didn’t supply the hospital with men. They came and dumped ‘wounds’: a lot of lungs, a fair amount of heads, a sickening number of underbellies and now and then, thank God, a leg, a foot, an arm: trios of lucky bastards.

Denis had been considered a lucky bastard, when they’d brought him in a few weeks ago.

In the tumult and the frenzy of the field hospital, the young doctor felt as good as useless. He couldn’t operate anymore and diagnoses in war time took only a glance. You just scanned for blood and missing parts. He walked through the rows of wounded who followed him with eyes full of silent prayers. They wanted a miracle. There were not enough bunks; many men lay on the ground in between. A disarray of bodies and faces, all coated with the sheen of misery.

Denis stood there, in this putrefied chaos, lost in thought. He was a tall, young-looking man of twenty-nine, a southern type with jet black hair, something almost Indian in the slant of his indigo eyes. His cheeks were covered with dark stubble.

He was handsome in a full-blooded way.

Even without his right arm.

Which was being touched now.

Marie Estrange, daughter of a wealthy wine merchant, war-nurse out of moral compulsion, had touched the air where Denis’s arm had been.

He had felt it.

She looked at him. Her big eyes were attentive, the broad curve of her full-lipped mouth was tight with concentration, and there was a haze of sorrow around her – which in Denis’s opinion was far more exhausting than mere compassion.

“How do you feel, Michel?”

He looked away, evading an honest answer. “Like an old man waiting for the end with the impatience of a young man.” Now, wasn’t that a bit melodramatic? He often didn’t find the right tonewhen Marie was near.

She took his left arm. “You can help me distribute water, old man with two forenames.”

His name – Michel Denis – had become a formal joke between them. His normal, sarcastic answer was, “Having two forenames means you don’t have family.”

Now he only nodded.

As Denis squatted on the ground, holding a cup of water to a feverish soldier on a make-do bed of straw, he felt a tingling in his neck. He looked over his shoulder. The eyes of The Mole were on him. Denis observed intently the silent message of that stare, and noticed the jaundiced whites of The Mole’s eyes. Liver problems? It contributed to the man’s eerie appearance – like a sleep-walker, neither awake nor asleep. A catatonic state due to shell shock?

“Enfants de Malheur,” The Mole said. “Children of ill-luck.”

Denis stood slowly. Since his amputation, he had the impression that his balance was different, less secure than before.

“Our suffering isn’t bad luck or an accident. We are the source of our own misery.” With these unctuous words, he hoped to make contact with the man. His words bounced back to him, like pebbles against a rock. The Mole let his yellowish eyes drift through the lazaretto. In a puzzled tone, he said, “Why do they hold on to life?” His eyes fixed on Denis. “Do you know why you want to live?”

The doctor’s irritation grew. This was not the time for petty philosophies. “It’s an instinct.”

“You live because you’re made and then you have to sit through your punishment.” The patient seemed to have difficulties with his vocal chords. He swallowed some syllables and his voice sounded querulous.

“We will pursue this conversation later,” Denis said, realizing how odd his formal behaviour was in these surroundings. The young doctor turned to give water to a soldier with a ghastly wounded face, his mouth a gurgling mound of blood.

“It’s not an instinct,” the half-strangled voice behind him said. “The desire to live is a disease.”

ChapterFive

That evening, the German forces started their offensive with a round of shells hitting Bois de Bolante. It was freezing. The sky was a dome of cobalt blue, pin-pricked with blazing-white crystals. A night in which wolves would hunt, the men muttered to each other.

As the biggest mortar shells exploded, their vicious sparks pierced the night sky with red and turquoise; trees were etched like charcoaled skeletons against metallic dark. When mortars fell into the woods, they exploded with yellow-blue flames which extinguished themselves slowly in the snow. Waves of green light were broken by shards of exploding shrapnel, whistling through the air like tiny red suns. Bullets whizzed like angry bees, softly thudding when they clashed into the frozen ground. The salvoes of the new, quick-firing German artillery were heart-stopping. They made a hellish sound: a lightning-fast roll on a giant drum. And in all that dazzling, reflected light, now and then the shapes of the soldiers in their trenches were sharply outlined, then torn apart in the play of light and shadow through the succession of flashes, colour, reflections.

Enfin, it was a motley funfair, the French told each other breezily, to puff up their courage.

The cries of the wounded were weak and pitiful in this cacophony.

After a few hours it became clear that the lazaretto had to be abandoned. Denis did what he could to help evacuate the wounded. The whole regiment had to retreat. The worst injured were left behind. It was a death sentence and everybody knew it.

The stretchers creaked in the brittle winter air. The wounded sighed and moaned. The shelling resumed: a razor-sharp sound in the sky, vibrating in their bowels. A word materialized in Denis’s mind: banshees. When had he read about those keening female spirits, wailing their grief in the face of death? He couldn’t remember. His mind was drowning in the ear-splitting sound. The exploding shells transformed the wood into an incomprehensible labyrinth. Were they heading for the Ravin des Meurissons, or in the direction of Fille Morte?

The retreat had started in orderly fashion but was now in disarray. The bombardment sapped their energy. Separated groups, following the Captain’s orders, tried to reach the Ravin, but they lost contact with each other. The fighting platoons, under command of Réviron, would do all they could to slow down the advancing Germans, but nobody in the shattered medical platoon could tell if it was working. The men existed in a shrunken world, hearing only the roar of war, seeing only the mesmerizing shafts of light, as fierce grenades ripped the trees apart. Denis fixed his gaze on the stalwart back of The Mole, striding in front of him. He noticed the man’s swagger, unexpected at such a moment, as his head swung rhythmically from right to left. He wanted to speak to that broad, strong back, so ominous one moment and so pitiful the next. I want to live because there is no alternative to living, he wanted to tell The Mole.

Or was there an alternative? Had The Mole’s mind retreated into some bizarre state of non-living? What was the madness that froze his features? The young doctor was reminded of Gogol’s Diary of a Madman.

Madness becomes a different kind of reason, a wisdom which reveals the truth, unseen by a sane person.

When had he read that? Surely during his studies. And was it even Gogol who had penned this observation?

They stumbled on, not a military unit anymore, but a pack of exhausted animals, in flight. Their bodies were cold as stone, their hearts haunted by fear.

There were not enough gurneys to transport all the wounded, so they kept switching. Those who were still able to move at all, tried to cover as much distance as possible.

With his one arm, Denis supported a soldier who had lost a leg.

Sanity was challenged by the wisdom of the mad.

Yes. That was Gogol, wasn’t it?

Time became erratic. Sometimes it sped up, then slowed down to the point of stalling. The din of war had not lessened: on the contrary. The medical platoon pushed on until, under an ephemeral morning sky, it reached the right bank of the river L’Aire.

The water was coated with greyish ice. Some men tested it. They muttered their uncertainty. A few of them wanted to follow the bank to the north. Others argued that this would render them too visible. The Germans would launch a gas attack the minute they discovered a group following the river. Marie Estrange, her pale face partly hidden by the hood of her raincoat, stood apart from the rest, gazing at the left bank of the river.

“We don’t have much choice, do we?”

The brisk daylight caused the wounded on the stretchers to sneeze. Marie’s eyes shone fiercely. Her voice, though soft and without emphasis, carried weight.

“We have to choose between fire and ice.”

It happened as in a dream, swift and intense.

A few meters from the other bank, the ice cracked beneath Denis’s feet.

A sliding sensation, his stomach lurching into his throat.

Someone yelled.

The water underneath the ice was black.

The water seemed to throw itself at Denis and the one-legged soldier.

Afterwards, Denis would remember the episode as if a vicious animal had indeed jumped out of the hole in the ice.

Slipping, the young doctor instinctively let go of the wounded man. Hands pulled him away from the hole into which the one-legged soldier disappeared without a sound.

Denis got to his feet, helped by the hands. He stared at the almost perfect circle of oily black water. A tingling sensation in his chest. He looked up. The Mole held him like he was a child. “I was prepared to die,” the patient said with that mechanical voice, “but now I realize I have to fulfil a duty: I must tell my story. It has to be chronicled.”

Before Denis could answer, Marie Estrange slid past The Mole, holding a blanket in her hands, wrapping it around Denis’s body.

“You have to keep on moving or you’ll die of frostbite,” she said.

Only then did Denis notice that his body was trembling uncontrollably.

ChapterSix

The regiment stood to attention in the freezing cold, listening to Captain Réviron’s pep talk in front of the recaptured field hospital. The Captain outlined in great detail how les Garibaldiens, the Italian volunteers who fought along with the French forces, had ultimately pushed the advancing Germans back. Listening with half an ear, Lieutenant Denis drifted away into a childhood memory. At nine, he had suffered an attack of diphtheria. It had been a snarling winter like this one. For several weeks, he lay in his bed, looking through the window at the lonely expanse of snow, cut into pieces by black grassland fences, the sky hardly distinguishable from the earth. It was a winter landscape that whispered many things just outside the range of hearing. The disease sharpened his ears, but dulled his reason. If he stared long enough, he saw things moving in that strange, lifeless landscape that seemed glued to the windowpane: things that crept stealthily toward a dead tree in the middle of the pastures, a long way from the woods at his right, as a curtain hiding the faery world he longed for. The stealthy things were furious, but he knew they wouldn’t harm him. His sickness protected him.

When he recovered, young Denis made it his habit not to look out of his window.

Now he stared at the back of a man in the row before him. In the past week, while the French forces were regrouping to fight their way back to the medical compound, The Mole – everyone called him that now – had been ordered to help in the field kitchens and the transport of the wounded. He obeyed every order without speaking, and he was useful enough: his broad, thick-limbed body could tolerate the cold and strenuous efforts. His face remained, as it had been since he was found, an Egyptian death mask. The French non-combatants had been ordered to hide in the few remaining houses of le village deBoureuilles until they could return to the field hospital in Bois de Bolante. As soon as possible, The Mole was to be handed over to the military or civil authorities. He had never given any trouble, but the men exchanged disgruntled glances behind his back. The story of his disinterment had been passed round in whispers, and the unnatural impassivity of his features led to theories which grew wilder by the day.

Was The Mole really suffering from shell shock? Denis had asked himself the question over and over. Was he faking it, hoping to evade a court-martial? Or was it a mild form of catatonia? An infection of the brain or a disorder like epilepsy could cause catatonia in various degrees. Denis knew that untreated catatonia could develop into stupor or dementia praecox. As a medical student, he had seen a patient lying in bed with his head poised inches above the cushion instead of on it. The man held that impossible position for weeks. No wonder that in Medieval times, catatonics were regarded as possessed by the devil. Denis had studied all kinds of ‘alternative’ medicine not included in the university curriculum. It was in his nature to search for holistic cures. He read the Organon of the German physician Hahnemann, a controversial figure who called his art of healing ‘homeopathy’, and was struck by Hahnemann’s conviction that insanity was a result of earlier physical diseases that had to be treated before one could cure the insanity. Denis had asked The Mole if he remembered any physical discomfort and had received a vague answer: there was a pain in his heart region. It felt like he had been stabbed there. However, the skin showed no stabbing wounds. Denis had briefly wondered why The Mole diagnosed the pain as a result of a stabbing, but the demands of repairing the compound were consuming his time and energy, so he hadn’t pursued this train of thought. Even Captain Réviron, who now dismissed the troops, seemed to have forgotten that only a week ago he had deemed it important to establish The Mole’s identity.

The man must have felt that someone was looking at him. He turned his head in that peculiar way of his, like a bolt being moved by a screwdriver. He looked straight at Denis. For one heart-stopping moment, the physician saw the eyes of the one-legged soldier he had lost to the hole in the ice.

ChapterSeven

Denis sat silently on The Mole’s bed. It was late, but the dormitory for the men who were fit enough to fight or to labour was never quiet. Dreamers muttered fretfully in their sleep; farts reverberated like tearing sandpaper; there were mumblings, groans and whisperings like small creatures colliding. The war had abducted the realm of sleep. During his round – he was responsible for the medical supplies – the young Lieutenant had noticed that The Mole was awake.

Denis could sense the man’s body heat, and smelled his musky, sour sweat. There came no sound, not a sign of discomfort.

“A physician and his patient share confidentiality,” Denis whispered. “It’s not my goal to report your real story to the Captain. Just tell me who you are, why you hid in that tunnel and how you manage to keep up that indifference of yours.”

To his surprise, there came an answer, although The Mole, lying on his belly, wasn’t looking up at him. Instead, he seemed to address something underneath his bed. “Tell me who you are… What an interesting question. Can you tell me who you are, doctor?”

“That isn’t the point. You are…”

“If you can’t tell me who you are, can you then perhaps prove to me that the world you are seeing is real?”

“I can touch it, sense it, see it, hear it, taste it.”

“That proves nothing. If you can’t tell me who you are, then you can’t rely on the senses of a self which is fictitious. Each man lives in his own dream and calls it ‘the world’.”

“That is solipsist thinking.”

“The world, as you call it, doctor, is like the shadows in Plato’s cave, a dream projected into our mind by the other in us. The Classics called that entity The Daemon. He who uses us as mules.”

“You can’t suppose I would believe that.”

“Don’t tell me you’ve never had the feeling there’s the voice of a stranger in you. It may warn you, it may insult you, it may predict your future, it may give you dreams which seem more real than what we call reality, it may trade you for a better mule, it can do a multitude of things, and it is eternal.”

The hole in the ice opened. Black water rose as though something underneath had stirred it.

Denis felt a sharp pain in his left knee. He lay on the floor beside his bed. Something warm trickled down his ear. Bemused, he touched it and felt sticky blood. He had bumped his head against the legs of the next bed when he had fled something in his dream.

Light footsteps, someone quick on her feet.

Before her hand touched his shoulders, he knewthat she would be the one who came to console him, and he heard an echo deep inside his body, like a sighing whisper.

What was the meaning of his nightmare? The Mole and his bed had seemed so real, the words he spoke so intrusive.

Marie mumbled something under her breath when she helped him to stand.

“How are you feeling?” she said, when he sat down on his bed and massaged the tender spot behind his left ear. He saw the concern in her eyes.

The whisper had sighed: She could have been the one.

What did this dizzying confusion mean?

Was he the one suffering from shell shock?

ChapterEight

The nightmare had its effect – the following morning Denis chose the abrupt approach. He had picked the moment intuitively. The Mole was sitting outside by himself, smoking a pipe and watching some men operating the pump set up between the trees. They were going for the biggest priority: dry trenches. The sky was overcast. Greyness skulked everywhere, draping its moist haze across the world. The trees, usually a deep brown wall, were enveloped in a shroud that from a distance resembled a dirty bed sheet.

As always, The Mole wore his serious and rigid expression. Denis sat down beside him, and, seeing that the man’s pipe was as good as empty, offered him some tobacco. The Mole accepted without a word, and filled his pipe slowly, concentrating on the task.

They both puffed smoke.

“You know,” Denis said, “nerve damage caused by a great shock can be temporary. You can be cured. The psychic turmoil you experience is ecstatic or doctrinal. Out of self-preservation, the ecstatic types withdraw into a world the mind creates for them, thinking that they cannot survive in the real world after suffering such chagrin. The doctrinal types react to the tumult of their life by nurturing some obsession so their mind can fixate on that and doesn’t have to take account of reality. I think you’re ecstatic. That type has the best prognosis for recovering sanity.”

Silence.

They smoked, and heard the men cursing as they handled the pump.

“Give me pen and paper,” said The Mole at last. “I must write my story. It has to be chronicled.”

Denis wondered about the formality of that answer and wanted to say: You see, here you go again, making yourself the centre of the world you’ve created in yourself.

He bit away his irritation and answered, “Fine, I’ll see to that.” Unexpectedly, it occurred to him that he no longer knew who he had been before a grenade had ripped his right arm from his body. What kind of person was he when his body was intact? Which dreams did he cherish?

He remembered searing heat, that was all.

“Time is running out,” The Mole said.

He didn’t tell for whom.

He didn’t have to. Out of its grey cloak, the war rose again, staging its booming sounds.

One moment, two soldiers opposite one another stood with their arms outstretched to push the pump lever down so that it looked as if they were saluting each other; the next, they were gone in blinding light and acrid smoke.

The shock wave toppled The Mole and Denis. Dazed, they lay partially upon each other on the soil. They smelled the stench of burnt flesh.

Their faces almost touched each other. Denis saw a predator’s look in The Mole’s eyes, fierce and intent. Then they changed, and Denis was face to face with a man lost in an inner inferno.

ChapterNine

Denis and Marie did not look at each other. They averted their gaze into the trees, the stars, their hands.

Blankets around their shoulders.

For the first time since Denis was wounded, they felt again a bond between them. But it was unclear what it represented, and they both had cautious and sensitive characters.

So instead, they talked about The Mole. They were young, so they tried to sound like professionals. They uttered the words ‘trauma’, ‘psychotic’, ‘maybe epileptic in nature, but not the Grand Mal version’, and ‘catatonia’. They mentioned Freud and Charcot; they talked about the very diverse symptoms of ‘hysterical neurasthenia’.

“Organic lesions in the brain, perhaps?” Marie suggested.

It wasn’t the first time that Denis was surprised by her knowledge of new currents in psychiatry. He had mentioned that before. She had answered that, as the daughter of a rich wine merchant, she had had all the time to buy books and read whatever interested her, while her older brother had been raised to take over the family business.

“Just before I had to interrupt my studies, one of our professors told us that they were experimenting with hypnosis for cases of psychoneurosis,” Denis said. “But, ironically enough, the influence of German psychiatry was so overwhelming that we were more obsessed with the nosology of psychic diseases – we developed a classification but fundamentally didn’t learn much about treatment.” He realized that he sounded pompous. Too late. The veiled subtext was undisguised: When the war broke out,I was in the last months before my final exams in psychiatry, and you’re just a nurse.

“Isn’t it the case that the nature of the delusion must be analysed before a treatment can be suggested?” she said. She had understood his unspoken message: I’m wounded and my ego hurts, give me the chance to distinguish myself.

He didn’t answer. They were silent for a while.

“I’m under the impression he’s doing some self-analysis,” Denis said. ”He’s writing in the grey notebook I gave him.”

“Writing?”

“He insisted that his story must be told. He mentioned it in a peculiar way – it has to be chronicled. I reckon he’ll write some far-fetched fantasy. That he’s in fact a king whose birthright has been stolen. Or a magician who’ll stop the war if he finds his magic wand.”

“That would make him a ‘normal’ lunatic.”

“I don’t know. He has a certain flair with words. ‘The world is an illusionist’s trick,’ he said. Sounded poetical to me. And not untrue, if you think about it. The world certainly feels that way sometimes.”

She laughed. The look in her eyes was usually rather stern, he thought, but when she laughed she narrowed her eyes into slits like horses do when they’re petted.

He took a book out of his pocket, thumbed through it until he reached the page he had marked and read aloud in English. “Page 32: Delusions are sometimes elaborated into an extraordinarily complicated system. Every fact of the patient’s experience is distorted until it is capable of taking its place in the delusional scheme.”

He handed her the book. She looked at the cover. Bernard Hart, The Psychology of Insanity, Cambridge, 1914.

“Your English sounds nice,” she said. “Now would you please translate it for me, Michel?”

You are nice too, he wanted to answer. Instead, he did as she had asked.

She tapped her index finger on the cover. “You’re very up to date.” For an instant, he wanted to say something about her use of an English expression, but he only nodded his thanks.

“I learned English because my father did business in England and I went with him on holidays.”

“Business as a promoter of polyglots,” she said, a little ironically. She didn’t ask him what kind of business his father did. He had noticed before that she didn’t seem to be interested in his family.

“You don’t like business?”

She avoided his eyes. “My father is a man of figures.” Her tone was curt; he decided to change the subject.

“My father told me once – I must have been eight or so – that one of our servants had gone mad and was taking advice from a voice that barked like a dog,” he said. “Afterwards, every time my beloved collie Laila barked, I told myself I understood what she said. That gave me great satisfaction. It took a long time – and Laila’s death – for me to stop believing that she barked at me that she would always love me.”

It came as an impulse, a reaction he couldn’t control.

He barked at her.

He saw the sudden fright in her eyes, then the barely withheld tears. He wanted to say he was sorry, but the echo of his barking seemed trapped between the trees.

She turned her back to him.

“I’m sure she still does,” she murmured.

The Mole’s Writings In The Grey Notebook I

i

1875

The Eidolon floats in a sea of sadness.

What is real and what is not?

Who am I?

We are we within we within we…

We are worlds within worlds within worlds…

I will create one for him.

I must give the Eidolon its name.

Who’s standing behind my right shoulder?

No breath reaches my skin.

ii

1875

Saint-Maclou is the anus of the Earth, Alain Mangin mused. The fifteen-year-old boy considered this trouvaille a literary feat.

Alain stood at the window of the attic in the manor house, overlooking the farmyard. The attic lantern, suspended from a beam, threw a honey-coloured shine on the wooden floor. Against the western wall, there stood a collection of big wooden puppets, carved by Alain’s grandfather in the tradition of the great Napolitano burattinai. In the middle of the attic, books from his father’s library lay scattered on the table. The morose atmosphere of the attic attracted the teenager.

Alain Mangin cherished a few vague memories of his father Raoul. The most beloved one was the image of Raoul in full military regalia during a parade in Paris ten years ago. Out of the same period came the strongest scene he retained from his early youth: a cacophony of voices in the shadowy environment of a raucous bar. His father’s laughter had been recognizable above all other sounds: heavy and testy, as though Raoul had to force each vibration from his throat.

The faces in Alain’s memory were distorted and eerie, like the faces of the puppets in the attic. A glass was held before his mouth. In a reflex the boy opened his lips and scowled when he tasted the sourness of the brew. The faces in the bar seemed to whirl like balloons, inflated, deflated, appearing, disappearing. In his memory, only the old woman in the back room had a body – bulbous breasts pressed together by a multicolour dress. The door behind him closed with a clap. The hubbub in the bar became a din. His father’s hand landed on his shoulders. He spoke to the gypsy woman. Alain heard the words, le futur.

The future was a thing without distinct meaning for a five year old.

The old gypsy placed her crystal ball on the table. During her long career in the working class districts of Paris, she had earned enough money to buy the finest counterfeit crystal. She also knew how a cunningly placed light source and a swift estimate of the customer could add an alluring aura to the tricks of her trade.

This customer was a godsend. The drunken fool wanted her to prophesy his young son’s future. The little one was spindly, with sheepish eyes, a petite bugger with an unhealthy blush on his cheeks.

“Gaze into my crystal ball, young sir,” the woman lisped, scratching behind Alain’s ear as she would caress a dog. “The whole world hides in it.”

The whole world hides in it. The ironic lie planted its fangs in Alain’s head and snuggled itself firmly in his brain.

Alain saw lights glittering in the ball, and his reflection, curiously changed, a dapple of yellow and shadows.

The gypsy took the glass-bead necklace on the table before her and held it behind her ball. A fake diamond oscillated at the end of the necklace. “Gaze into the stone of Padua, petit seigneur!” she said, with her phoney posh accent. “Through its magical powers, the world opens itself like a breaking egg…” With her fingertips, she deftly turned the counterfeit diamanté, which borrowed the light shining through the ball and scattered it from its many facets. She had learned that trick from her mother, who had learned it from hers.

“I foresee that your son has the ability to become a talented general, should Fate help him,” she said, glancing at the father. She smiled with parted lips – she had been beautiful once.

At home, Alain had a gaudy-coloured tin soldier carrying a rifle in his hand. General. He knew that word. He gazed at the glittering light emitted by the cut glass in the ball and saw himself in a white uniform with golden tresses and a shiny sabre.

The boy smiled.

“This young lad shall witness the world’s Fate,” the gypsy went on. She saw the father frown. Had she gone too far? She didn’t care. Fortune-telling in the back room of a bar was always the best – the boozers were easily besotted. What the hell, she would smear it even a little thicker. “In days yet to come all men shall know his name.” She liked the ‘In days yet to come’ and most of her customers were impressed by it.

Raoul Mangin, his head a cobweb of fleeting, colliding thoughts, burst into laughter. A funny old crone, worth a coin. “Here you go, toad-eater.” He handed her a copper and grabbed his son by the collar. Alain wanted to stay and look at the light-dazzling stone, like a tiny star that the gypsy held behind her ball. He tore himself free from his father’s hand. Raoul laughed again in his intense way. “Didn’t you hear what Madame said? Maybe you’ll become a mighty general. But even a general has to start as a soldier and follow orders.”

Alain, propelled by his father’s hand on his shoulder, stumbled back into a world of banter, harsh noises, red, puffed-up faces and wine.

Much later, at home, the noise was as deafening as in the bar. His mother’s angry shrieks exhausted him. He felt feverish. On the table stood a lamp with a big belly and beads dangling down from the lampshade. Alain sat at the table and imagined he was looking in the crystal ball again. The ball swelled before his sleepy eyes. He saw himself afresh in that lovely white uniform with golden tresses. Suddenly, his father’s hand appeared above the table, smashing the lamp. It scattered in fireflies of light, fading away quickly. Father’s voice, loud as usual, mother’s yelling. Alain put his hands on his ears and felt himself falling into a depth that made his body heavy like a lump of clay.

The boy didn’t realize that he was falling from his chair.

His body arched under the pressure of an invisible power.

Over and over again in his young life, Alain had revived the memory of his first epileptic attack. It stirred in him a longing for beauty, and summoned the tyranny of fear.

On the left wall of the attic, beside the bookcase, hung a small painting. His father Raoul had painted it. The military man had cherished artistic dreams for a while, but had been too proud to pander to the tastes of the Parisian bourgeoisie. “Those intellectuals like to pontificate about art,” he liked to say. “But Art cannot be analysed. Colours are like bodies, Alain, they must live.”

All those years Alain had listened to his father’s monologues, silent, trying to understand the man who introduced himself to visitors as ‘the painter-lieutenant’. His mother only praised his father when he was ready – in full regalia, though with a cranky face – to conduct her to a dance hall.

The painting presented a human form in rough, terracotta brush-strokes. Was it a man or a man-ape? The pot-belly was pushed forwards by the unnaturally crooked back. The creature held one hand up above its shoulders. The hand resembled a claw. All in all, the painting was a brooding collection of sweeping lines that conveyed a mixture of anger and disgust. The ‘face’, with its contorted mouth, resting without a neck on that crumpled body, had a tormented expression. Since the day of his visit to the gypsy woman, and his parents’ quarrel afterwards (which nestled in his mind as ‘the fight for the Stone of Padua’) he had regularly suffered from Grand Mal attacks. As he gazed on the painting of the man-ape, it seemed to Alain that his father had portrayed him.

An enigma, his papa. Two days ago, Alain had marked a passage in one of the books that were part of Raoul’s legacy: The male body has nothing in common with a reservoir, the female sexual parts act like one. Thus they incite the male toward the act of sex by piquing his need to release and to detumesce. Due to the external shape of his sexual parts, this urge is very powerful in the male.

For days, he had been trying to decipher the meaning of these awkward sentences, wondering why his father read something like that, while he had many other books full of sonorous poems, or tales of wonderful adventures and travels.

He remembered his father as someone who stood for long periods at the window overlooking the garden of their Paris home. Sometimes, Alain went and stood beside him and before long, one of Raoul’s gnarled hands would rest against the nape of his son’s small neck and lightly squeeze it.