7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

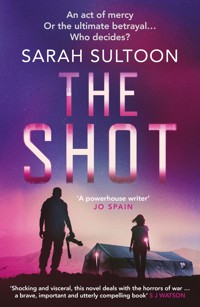

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

An aspiring TV journalist faces a shattering moral dilemma and the prospect of losing her career and her life, when she joins an impetuous photographer in the Middle East. 'Shocking and visceral, this novel deals with the horrors of war … a brave, important and utterly compelling book' S J Watson 'Gritty, hard-hitting and often harrowing … a hugely exciting voice in crime fiction' Victoria Selman 'A powerhouse writer' Jo Spain –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– An act of mercy Or the ultimate betrayal… Who decides? Samira is an up-and-coming TV journalist, working the nightshift at a major news channel and yearning for greater things. So when she's offered a trip to the Middle East, with Kris, the station's brilliant but impetuous star photographer, she leaps at the chance. In the field together, Sami and Kris feel invincible, shining a light into the darkest of corners … except the newsroom, and the rest of the world, doesn't seem to care as much as they do. Until Kris takes the photograph. With a single image of young Sudanese mother, injured in a raid on her camp, Sami and the genocide in Darfur are catapulted into the limelight. But everything is not as it seems, and the shots taken by Kris reveal something deeper and much darker … something that puts not only their careers but their lives in mortal danger. Sarah Sultoon brings all her experience as a CNN news executive to bear on this shocking, searingly authentic thriller, which asks immense questions about the world we live in. You'll never look at a news report in the same way again... –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– 'A powerful story of the brutality of front-line journalism. Authentic, provocative and terrifyingly relevant' Will Carver 'A gritty, jarring page-turner' Peter Hain 'Passionate, disturbing storytelling at its best' James Brabazon 'You won't read another book like this in 2022! Raw, authentic, powerful ... you won't see the end coming!' E C Scullion 'Brilliantly conveys both the exhilaration and the unspeakable horror of life on the international news frontline' Jo Turner Praise for The Source **Winner: Crime Fiction Lover Best Debut Award** 'A brave and thought-provoking debut novel' Adam Hamdy 'A taut and thought-provoking book that's all the more unnerving for how much it echoes the headlines in real life' CultureFly 'A tense thriller, a remarkable debut, heartbreaking, but ultimately this is a story of resilience and survival' New Books Magazine 'A powerful, compelling read that doesn't shy away from some upsetting truths … written with such energy' Fanny Blake 'Tautly written and compelling, not afraid to shine a spotlight on the darker forces at work in society' Rupert Wallis 'So authentic and exhilarating … breathtaking pace and relentless ingenuity' Nick Paton Walsh, CNN 'A gripping, dark thriller' Geoff Hill, ITV 'My heart was racing … fiction to thrill even the most hard-core adrenaline junkies' Diana Magnay, Sky News 'Unflinching and sharply observed. A hard-hitting, deftly woven debut' Ruth Field 'A hard-hitting, myth-busting rollercoaster of a debut' Eve Smith 'I could picture and feel each scene, all the fear, tension and hope' Katie Allen For fans of Holly Watt, Sarah Vaughan, Laura Lippman and Karin Slaughter

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 429

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Samira is an up-and-coming TV journalist, working the nightshift at a major news channel and yearning for greater things. So when she’s offered a trip to the Middle East, with Kris, the station’s brilliant but impetuous star photographer, she leaps at the chance.

In the field together, Sami and Kris feel invincible, shining a light into the darkest of corners … except the newsroom, and the rest of the world, doesn’t seem to care as much as they do. Until Kris takes the photograph.

With a single image of a young Sudanese mother, injured in a raid on her camp, Sami and the genocide in Darfur are catapulted into the limelight. But everything is not as it seems, and the shots taken by Kris reveal something deeper and much darker … something that puts not only their careers but their lives in mortal danger.

Sarah Sultoon brings all her experience as a CNN news executive to bear on this shocking, searingly authentic thriller, which asks immense questions about the world we live in. You’ll never look at a news report in the same way again…

The Shot

Sarah Sultoon

CONTENTS

For all the photojournalists. And for Geoff Hill – a warrior.

Prologue

The man, he’s tall, with a ranger’s lope and a marked imbalance in the square of his shoulders that characterises years working with a piece of heavy equipment on one side. He’s done this many, many times before – there’s a heft to his frame, an almost balletic glide to his movements as he sweeps around, camera tucked light in the curl of his arm. But look closer and there’s a stoop, a hunch to his back – he’s weary of it, even if he’s still a master of his own choreography. On the rare occasions his eye leaves the viewfinder it snaps primary-blue in the glare, looking away for just long enough to allow a puff of air onto the sweat beaded inside the tight rubber seal.

The girl, she’s slight, but with none of the man’s long-rehearsed physical grace. Her dark hair is fighting its cords, wisps escaping from below a cap only to write themselves all over the perspiration on her neck. She’s stumbling behind the man, twisting this way and that, peering over her shoulder in random directions but finding no alternative point of focus. She doesn’t know where she’s going, nothing is as she expected but, thanks to him, she’s not lost. While both figures are dressed in the stained fatigues of war, otherwise appropriate to the scene they’re in, their manner sticks out from the sepia landscape as much as that of the doctors, white-coated and flitting like sprites around the medical tent, with little they can do for anyone inside.

Here, there are only victims. There are no survivors. Here, enfolded in the vast plains of the Sahara, there is a war raging that no one else wants to see or hear. And here, the unforgiving desert can bury the evidence whole with the merest flick of a sandstorm’s tail. It is the cruellest of ironies that the state-sponsored militia pillaging this land have Nature on their side too. By the time anyone is inside this particular medical tent, there is no hope left. The only peace lingers in the air above the corpses – isolated little eddies of it, circling with the flies above shroud after shroud. There are other bodies, but they are the undead, the peaceful fate they crave so close that they can touch it in their wounds, which weep into the air, their eyes having no tears left to shed.

They can no longer feel. No comprehension remains. Here, there is nothing left to live for, only nightmares to dread.

The girl, she is holding a microphone. It’s thin, like an extension of her arm, almost too feeble to bear the testimony she is gathering. The man, he still has poise about him, his movements calm and deft, but he gets to watch from behind a lens, from deep inside his own personal bubble. It’s not just sweat inside the viewfinder, he’s blinking away the tears, but that’s his own little secret. No one else need ever know. This is a bubble that always bursts, but for now, it’s his only protection against the catatonia of grief, the cacophony of despair, a crossfade of past and present, the here and now blurring with scenes he’s long buried in his past. For now, her ears are tin, his eye is blind. Their bodies are operating in a pre-programmed trance.

Look closer, you will see a logo on the girl’s cap – letters all twisted together, embroidered neatly in fire-engine red: an international news network, another type of rescue service, another type of microphone, only with a far wider reach. The doctors, the aid workers, they all know that logo, they hope even the slightest amount of overseas attention might bring more relief equipment, more food, more medical supplies to their inadequate arsenal. They even dare to dream it might bring intervention, and so they clear the path towards a long, thin bundle wrapped around another, far smaller bundle – a mother, Yousra, cradling her baby son, Ahmed. You can see the bundles are still breathing, their chests are puffing in and out. But the small one has only minutes left before prolonged malnutrition overcomes his still-nascent heart and lungs.

There are questions, and there are answers. There were men on horseback, there were guns, there was fire, there was death. The language varies, from English to Arabic and back, but never settling on anything that makes sense. Are those really a clump of Sudanese desert flowers, peering beguilingly from just outside the flapping tent doorway? Or is it Nature playing yet another joke at their expense? Still the camera rolls, the shutter clicks, the record is set. And before long, there is film; proof that will end a war, launch a career, and sell millions and millions of magazines. A shot that will tell a version of this story that finally sticks.

But the girl, she’s trapped in an endlessly repeating scene inside her own head: a dusty afternoon, a stifling-hot apartment, her father, her paint-box, his camera. She was too young to look at his pictures, so she contented herself with painting her own, filling the weeks he was away working in countries she couldn’t pronounce, witnessing events she couldn’t understand – dreamlike places that became the centre of her nightmares after one eventually claimed him for good. They’d moved all over the Middle East, from Cairo to Amman to Beirut, in pursuit of his job, but she didn’t care, until he never came back.

Here’s the shutter, her father had said, brushing a fingertip over her sweaty eyelashes, tapping another against the front of the heavy black case in his lap. That’s how the eye traps the light, how it sends a picture of what it sees into the brain. And this, he’d continued, pointing at her eyes, wide in the mirror embedded inside the lid of her paint-box, this delicious chocolate-brown circle is the iris. That automatically regulates the amount of light sent through to the back of the eye by changing the size of the pupil.

So the brain has to tell us what the eye sees? she’d asked, staring into her own eyes, squinting between the traces of powdered paint on the mirror. That’s right, her father had answered from between his teeth as he lit a cigarette. The eye just gives us the picture, the brain tells us what it is. But the camera, the camera can give you any picture you want, if you know how to use it. The camera can move the angle, change the perspective, leave clues that the eye might never have registered alone. Sometimes, he’d added, smoke furling ruminatively into the thick air as he tapped his temple, sometimes the camera can do the job of both the eye and the brain.

Her mother had leant over then, pinching out the cigarette between his lips with a look the girl pretended not to see. There’d been lots of those looks, with words she hadn’t understood to go with the stories she wasn’t allowed to hear. So if you want to make your painting realistic, she’d said, tapping the sheet of paper on the table, you’ve got to use black in the eye. And if you’re framing a shot, her father added as he frowned back at her, that’s where the shadows have to be perfect. The darkest part of the human body is the pupil.

But it’s only when she saw death up close that she knew they were right.

Because it’s only in death that light finds its way into the eyes. They become spectral, with depths suddenly as transient as a last breath. A permanent mark of the moment where possibility becomes impossibility, where hope fades to peace.

The giveaway is always in the pupil.

The girl blinks and blinks until it hits her. The light, blooming from Yousra’s telescope-dark eyes – radiant, unmistakable. How frail is the curtain between her world and theirs.

She finds the man, his gaze blue as desert flowers, as sure as blossom that grows from dust.

And then the girl makes sense of it. Her brain catches up. The bubble bursts, the trance lifts. In rushes the storm.

For Yousra was already dead. And the evidence was all on tape.

Chapter 1

Risk

Six months earlier: November, 2003

The red phone rang first. It was the only red one in the tangle of black handsets littered over the news desk. It was nicknamed the ‘batphone’, but its plastic handset and cradle were the colour of running blood. I don’t think anyone had ever noticed that before it rang that day.

I felt it before I heard it, tidying the newspapers strewn all over the place as Diana and I got ready to leave. The vibrations trembled through the pages in my hand a nanosecond before the speaker kicked into gear. Still I didn’t dare pick it up, even as everyone else dived for the black phones on their desks. It was like watching a crowd realise they’ve all boarded the wrong train and have seconds to get off, heads swivelling in sync towards the red phone as the realisation dawned. The red phone is actually ringing. Hardly anyone had the number. It could only mean one thing. The mental alarm bells were still deafening long after Penny finally grabbed it.

I saw it before I heard it too: her face leached of all colour before she cried out, dropping the handset like it was as hot as it looked. She recovered almost immediately, wiping a hand on her suit jacket before picking it up again, but I saw it: she was sickened and terrified. I knew what she was going to say before she did.

‘Kris has been shot? And Ali too? What happened? Is everyone else accounted for?’

Penny’s next sentences came in two halves – one directed at the cluster of us on the news desk, the other to the person on the end of the line. I knew who it was, because I knew what must have happened. Kris was the network’s news cameraman covering the war in Iraq. The fighting had been raging for eight months, each one hotter than the last.

‘Di, quick, go and get Ross.’ Penny sounded like she was being strangled as she issued instructions before turning back to the receiver. ‘Where are they now? They were in convoy, surely, so what happened to the other car? Wait – which field hospital?’

Ross managed the photographers. He’d usually be downstairs in the crew room, managing via chatting and sorting through camera gear, his own brand of bringing order to chaos since he’d stopped travelling with his own camera himself. The air was suddenly electric, Diana’s curtain of blonde hair lifting strand by strand behind her as she ran off.

Penny covered the receiver with a hand again, shaking her head at the man working on the news desk next to me.

‘Mike, I need you to call DC right now – get them to raise their most senior contacts at the Pentagon.’ I watched her face colour as she returned to the handset. ‘I thought you said it was the Americans running the field hospital?’

Her colour deepened, and Penny didn’t colour easily. You stop blushing practically before you’ve started if you run an international news operation.

‘Of course we won’t call anyone on the ground without running it through you first,’ she replied. Her hand shook as she smoothed hair off her face. ‘Who’s with them on site? What, you’re sending Mohammed out too? Why?’

Acid stole up my throat. I knew exactly where Mohammed would be heading. Ali was an Iraqi staff member, a Baghdad native, paid to translate, fetch, carry, explain, wheedle, arrange, you name it. He and Mohammed were the bedrock of the network’s Baghdad operation, taking risks far greater than any journalists did, just by being the ones who helped them. They kept people like Kris safe. Now someone was going to have to tell Ali’s family what had happened to him. They would only understand it coming from Mohammed.

Penny’s face burned as she scribbled on the pad in her lap. Feeling sorry for Penny should have been way down my list of emotions at that moment, but I couldn’t help it. Sure, she enjoyed all the bells and whistles that came with being the managing editor of the industry’s pre-eminent international news network. She had the shiny glass corner office, the personal assistant, the responsibility for countless decisions per day that had the potential to change the course of lives around the world – and not just the lives of those who were carrying them out. But I’d heard her pleading with her children after she missed yet another school event, begging someone at the end of the line to take care of family issues for her after yet another late night. I’d seen her eating crisps and chocolate from the vending machine for every meal – even her assistant too busy to buy her a sandwich. Then there was the tell-tale paler circle of skin around the third finger of her left hand where a ring once proudly sat. Penny made sacrifices too. She just didn’t make them on tape.

Still I found my sympathy evaporate as I caught her eye, phone jammed to her ear. To me, these sacrifices were ultimately a privilege.

‘Can’t you leave someone on the line with me before you head out? Andrea’s there? Perfect. Andie? Are you alright?’ I physically felt the depth of her sigh as she exhaled, noticing that she didn’t thank any higher power. Anyone who still did that hadn’t seen enough. ‘Bear with me, love, OK? I need you to hang on this line for a bit, just until we know what’s what. Give me a second to make a few calls and I’ll be right back with you, I promise.’

Penny placed the handset down on top of the pile of newspapers I’d tidied, the neat stack holding the phone high above the chaos. No one ever read past the front page but I could never be the one who threw them out. What if we found out we’d missed some critical editorial detail – that our competitors had a nugget of information we’d overlooked? Now all those papers would forever remind us of everything we’d misjudged that day. Was that why Penny sent Di to get Ross, instead of me? Was I already subconsciously connected with failure rather than success?

I looked away, found my comfort blanket – the enormous framed photographs lining the wall leading to the newsroom doors. Mounted like trophies, one iconic shot after another. I squinted as if I could read the credits even though I knew they were on the back. And that Kris was behind every single one of them.

People only ever remember the pictures themselves. They never think about what it must have been like to take them.

‘Penny,’ Ross huffed as he arrived at the desk, puce in the face from running up the stairs, sweat patches already pooled all over his cargo shirt. ‘What the hell happened? How bad is it? Who have you got on the phone?’

‘Andie.’ Penny tossed her head towards the red handset, another phone already in her hand. ‘Hang on before you speak to her though – she isn’t with them—’

‘I’ve got an official from the Pentagon on the line,’ Mike interrupted, braying from across the desk. ‘Jennifer wants to call every US general she can, connect them with the field hospital now, make the doctors aware of who their patients really are. Can I go ahead?’

‘Get me on the line with Jennifer,’ Penny shot back. ‘I need to talk to Katja before she does anything else. But good work, that’s great.’

Katja. A shiver went down my back. I was right. It had been Katja on the red phone. The news network’s chief field producer. They even called her an executive despite the fact her ‘office’ was almost always a tent or burned out building. And Jennifer was the channel’s US affairs editor at the time. Between them, there was nothing they hadn’t seen on the rest of the world’s behalf – Bosnia, Somalia, the First Gulf War. Except I knew this was the first time any of this network’s staff members had been critically injured.

‘How bad is it?’ I could barely look at Ross’s face as he asked me this time, slicking sweat off his corrugated forehead with a pudgy hand.

‘I don’t know,’ I whispered below Penny issuing sharp instructions to a sea of different people. ‘I don’t think anyone does. It’s only just happened. I heard Penny ask about a second car – I don’t even know who was travelling with them, or where they were going, just that Kris and Ali—’

‘You!’ Penny called. It took me a moment to realise who she meant. ‘I’m sorry –what’s your name?’

‘Samira,’ I stuttered, swaying as I stood up, a curious mix of excitement and terror coursing through my body, not sure whether to fight or fly. I wanted to be part of this, no matter how bad it was. ‘I work with Diana, we … It doesn’t matter. What can I do?’

‘Just sit on the end of that phone.’ Penny pointed at the red handset. ‘Don’t leave the line unattended for anything. Andrea is on the other end – do you know Andie? Actually, never mind … just stay on the phone. Whatever Andie tells you, tell me. And be there for her, OK? She’s already been through a whole lot.’

Penny whirled away before I’d even started to nod, trying and failing to blot my sweaty hand on my jeans before I picked up the handset. All I could hear was scuffles and muffled shouts on the end of the line.

‘Hello? Is that Andie? This is Samira, I’m a graphics producer – I work on the morning shows … Hello?’

‘Hang on, Mohammed – yes, sorry, hi there.’ Andie’s cool South African lilt floated down the line, improbably calm. ‘Just give me a minute, OK? Samira, you said? I’ll be right back with you, I’m just getting Mohammed out of the door.’

‘Of course, of course,’ I said, swallowing. What she had to prepare Mohammed for was unimaginable. He was an Iraqi staff member too. It could have been him. Now he had to be the one to tell Ali’s family that it wasn’t. I strained to hear her comforting him, but all I got was white noise.

‘Sorry, Samira, I’m back with you now.’

‘I’ll be on the end of this line at all times if you need anything. And if you could let me know any new developments as you get them, I’ll be sure to pass everything on to Penny.’

I knew I was gabbling at her. But if I stopped talking for too long I might hear my own fear.

‘Hang on again, sorry, Samira…’

‘Everyone calls me Sami,’ I told her, even though I knew she wasn’t listening. Why on earth would she? What was happening here in the newsroom was nothing to what she was fielding on the ground.

‘What’s going on?’ Penny mouthed from across the desk, a different phone cradled between her shoulder and ear. ‘I’ve got Katja back on this line but the connection is terrible.’

‘Penny, look.’ Diana’s chair fell backwards with a crash as she stood, grabbing Penny’s arm. ‘They’ve got it.’ She pointed at her computer screen.

All around me, red straplines were flashing on every monitor. Somehow word had got out on the ground that Western journalists had been injured. The news wires had it, and weren’t waiting to tell everyone else.

—BREAK: UK news crew ambushed in Iraq

—BREAK: Critical injuries in UK news crew attack

—BREAK: Mortars, gunfire heard in Baghdad ambush

I clenched the red phone, Penny’s eyes darting as she replied.

‘OK, Di, I need you to get hold of every major news network’s London office as fast as you can. We absolutely must ensure a complete news blackout. The victims’ families haven’t been informed yet. Take any and all offers of help … Yes, Katja? Katja? Can you hear me?’

‘What’s going on?’ Ross reached for her arm. ‘Where is she now?’

Penny gulped before she could continue, covering a receiver with a hand. ‘She’s on her way to the field hospital. Everything happened right by an American checkpoint, I think, I can hardly hear her. It seems like Kris and Ali were in the rear car, and that’s why they took the brunt of it.’

‘Brunt of what? The gunfire?’

‘I don’t know, Ross. I still don’t know what actually happened – I don’t even know where they were going. I haven’t approved anyone setting foot outside the bureau cordon for days. But I have to believe they were travelling in a convoy, no one moves in a warzone without a safety car on my watch. Christ, if I find out this was Kris haring off on one of his own madcap missions I will shoot him myself.’

A cold wash of adrenaline flooded down my back as Andie came back on the line, muffling everything Penny said next. Not that it mattered. I’d heard it all before: the risks Kris took to keep us ahead of the competition. The images he returned with that finally changed the record. My rush intensified, even though I didn’t know whether he’d got away with it this time. People like Kris were extraordinary. Anyone who couldn’t see that wasn’t looking closely enough.

‘Sorry, Samira, I’m back with you now.’

‘I’m here,’ I replied hastily, dragging my eyes away from their tableau. Penny seemed to be getting smaller and smaller, dark suit jacket blurring with her dark hair as she hunched over the desk. Ross, by contrast, seemed to be getting bigger, shirt straining over his chest and cheeks puffing in and out as he took deeper and deeper breaths. Suddenly all the jokes about every year Ross spent behind a desk adding another notch to his ever-widening belt seemed in terrible taste. The reason he sat there the whole time was to anticipate any hidden tripwire that would result in an eventuality like this.

‘How are you doing?’ The words were out of my mouth before I could stop them. As if Andie would possibly want to engage in small talk. I had played out her field-producer role a thousand times in my head; it was all I’d ever wanted to do myself. Get right to the heart of the story on the frontline, no matter where it was, no matter what it took. No time for small talk. But now here she was replying without even a hint of panic in her cool accent.

I shouldn’t have been surprised. That’s the emotional load we’re all expected to cope with. That’s the job. We’re supposed to understand it without ever talking about it.

‘Yah, we’re hanging in there. It all happened so quickly but I think everyone is in the right places for now. Mohammed is on his way. I think Katja has made it to the field hospital – you probably know more about that than me, hey? We were lucky, at least, that it happened close by, and I’ve managed to get everyone else under the one roof, if you want to pass that on to Penny. It’s Samira, right?’

‘Everyone calls me Sami,’ I repeated idiotically. ‘I’ll let Penny know as soon as I catch her eye. I think she’s on the phone to Katja.’

A sharp intake of breath. ‘Katja? What’s the latest on the boys? What has she said?’

‘Nothing that I can tell, to be honest. It’s all a bit crazy in here.’ I gazed dumbly around the news desk, every single phone off the hook, everyone on their feet. Usually this sight did nothing but thrill me. Now the balance was completely skewed.

‘I’m sure it is,’ Andie said. ‘My, it doesn’t matter how much you prepare yourself. We cover these sorts of incidents all the time, hey? Kris is always the one doing it, too.’ I heard her catch her breath again. ‘They were just … oh, I don’t know. Kris’s paperwork needed renewing. They’d barely had breakfast and loaded up, before—’

‘So they weren’t even going out to film a story? Or at least do an interview?’

I couldn’t help but ask, even though she hardly heard me. Later I would reflect on how seedy it felt, but it turned out not to matter in the end.

‘—his accreditation had expired. Ah, Katja was furious! You can’t move without a badge around here. And to think we nearly didn’t send him out with a security car. They wouldn’t have made it to the field hospital without Adam in convoy. We were so lucky.’

Adam must be one of the security advisors in the Baghdad bureau, I thought, nodding as if she could see me. Another role I’d imagined a thousand times. These men were stuff of fable, all former members of the SAS or similar, having left the military to take up one of the thousands of well-paid private security jobs springing up all over the industry after 9/11. Once one media company used them, everyone basically had to follow suit as their insurance companies started writing it into policy. It all sounded so romantic, I’d naively thought at the time. Now even news crews had bodyguards.

‘Do you know … do you know what actually happened?’ Maybe it would help her to talk it through, I reasoned.

‘Only that their car took small-arms fire. I don’t know how or why. I don’t even think Katja does, and Adam hasn’t had a second to speak to anyone except the medics at the field hospital.’

‘I’m so sorry, Andie. You’re doing such a good job holding it together at the office. Just hang in there, OK? As soon as I hear anything that you haven’t, I’ll pass it on, I promise. And so long as we keep talking to each other, we can’t lose our connection.’

‘You’re very kind, Samira,’ she replied, as I wondered where my words were coming from, muscle memory in some long-buried corner of my mind. ‘Tell me something, anything. I’m all on my lonesome here suddenly. My, I don’t think I’ve been left alone even once since I got out here. What’s everyone doing right now in the newsroom?’

I gazed around from my perch on the stack of newspapers. Ross was downing a bottle of water, running a hand through his hair, eyes skyward and fixed on some faraway point deep inside the lighting rig on the ceiling. I knew he was preparing to call Kris’s wife, running through his first sentence, then second and third.

What would he start with? Give her a moment to sit down, collect herself? Insist that someone was with her before he continued? And what would he say? That Kris’d been shot but he didn’t know how bad it was yet? I had to tear my eyes away, only to find Penny bent over the desk directly opposite, hunching lower and lower with a phone to each ear. A stream of grave-faced photographers were slowly clustering around Ross, as news of Kris’s injuries percolated through to the crew room downstairs. And around the rest of the newsroom, a curious suspended stillness; producers with their hands frozen above their keyboards, frown lines etched into the foreheads, chatter paused mid-conversation, as they watched and realised this was not a breaking-news incident to which they were all so accustomed.

This time, it was happening to us. We were the story. Exactly what journalists should never be. I took a deep breath.

‘Well, I can tell you there isn’t a soul in here not focused on the boys’ survival. There is nothing more important in this room than what’s happening to you all right now. Penny is on the line with Katja, and at least ten other people by the look of it. I know everyone else on the news desk is ringing round all the other networks to make sure nothing leaks before their families have been told. And Ross is up here too, along with all the photographers that were still in the building.’

‘Does Lucia know yet?’ Andie’s voice finally cracked. ‘Is someone on their way out to their house at least? To tell her in person?’

‘I’m not sure I know who you mean?’

I swallowed into the brief silence on the other end of the line. I didn’t want to admit to myself why I was making her spell it out. The rumours about Kris and Andie had been all over the newsroom for months.

‘Someone must be going to tell Lucia,’ she said again, clipped and sharp. ‘She’ll have prepared for this, of course she will. This is only the hundredth time Kris has been deployed in a warzone. You don’t marry someone like that without—’ Her voice cracked again. ‘Without knowing what you’re signing up for.’

‘I think Ross is preparing to call her now,’ I said softly, looking at my feet. The red phone suddenly felt like a brick in my hand. If I could have thrown it, I would.

‘So tell me, Samira,’ Andie said after a moment’s coughing into the receiver. ‘What is it you do in the newsroom? We’ve not met, have we?’

‘I’m a graphics producer,’ I said, watching Ross compose himself before walking slowly towards his office behind the news desk, a few photographers trailing after him. ‘I’ve been here almost a year, I was an intern to start with but I was lucky. They were shorthanded on the morning shows when the war started so I volunteered for the graveyard shift.’

‘My – so you’ve been working through the night?’

‘I guess so, yeah.’ I gazed at the bank of digital clocks running along the edge of the newsroom set, all blinking different times, suddenly aware how tired I was. ‘Although it depends which clock I look at. If I linger on Asia Pacific, I can pretend it’s the end of the day, even though I haven’t had breakfast yet.’

Andie let out a short, hollow laugh.

‘So what time is it in Baghdad now?’ I asked, even though I knew. The Middle East clock was flashing red directly in front of me.

‘It’s just gone eleven – wow,’ Andie sighed heavily into my ear. ‘Last time I looked at my watch none of this had even happened and now…’

‘Try not to think about it,’ I said confidently, even as at that moment Penny suddenly straightened up, eyes wide with horror. ‘It doesn’t matter. Nothing can change what’s already happened. All that matters now is what happens next—’

‘Graphics, you said?’ she interrupted, all clipped again. ‘What kind? You mean maps, fonts, graphs and such?’

I sighed. ‘Nothing that’s usually that interesting, unfortunately. Usually it’s just the words that run along the bottom of the screen. It sounds mindless, I know, but if a death toll changes or a news story starts to move really fast, then mistakes in the graphics are all anyone ever remembers. It’s really important to keep them accurate and relevant.’

‘Right, right,’ she said quietly, suddenly sounding the miles away that she really was. I plucked at the edge of newspaper bristling under the red cradle. I hated being spell checker in chief. It was just a means to an end.

‘And where are you from originally, Samira?’ She elongated my name – Sah-Meer-Rah. Later I would wonder if it was really just down to her accent or it was something else that made her do it.

‘I’m from here, except I’m not. Like loads of us in this business, I guess.’ I heard Kris’s broad Kiwi accent in my head as I said it. ‘My dad was Egyptian. I was born in Cairo but went to school here because my mum’s English, and he worked away a lot.’ Now I was trying to read Penny’s haggard expression.

‘So you speak Arabic?’

‘Some…’ I trailed off as Penny visibly trembled, the pit of my stomach following. ‘Yes. It’s not perfect but I’m hoping it will get me where I need to be.’

‘Samira…’ Andie’s voice sounded even fainter on the end of the line. ‘Has … has something just happened?’

I’ll never know what it was, in that moment, that told her something had changed, something irreparable. But I realise now that I already knew, the minute I saw Penny physically pull herself together, saw Mike and Diana freeze in their seats. The red phone suddenly became as fluid as an open wound as I dropped my head, my eyes filling with tears.

‘Samira? Can you hear me back there?’ Andie’s voice floated somewhere as I tried to compose myself. Penny’s face was set to a mask opposite, the only visible sign of emotion the tremble in her finger as she beckoned for me.

‘Just one second, OK, Andie? I’ll be back with you as soon as I can, hang on.’

I laid down the handset next to its red cradle, positioning both as far inside the square stack of newspapers as possible so they wouldn’t be disturbed, before picking my way round the desk to Penny, willing that no tears would escape down my cheeks. Nothing could be worse.

This isn’t my story to cry over, I repeated like a mantra in my head.

‘It is imperative that Andie does not find out from you, OK?’ Penny kept her voice low as I approached. ‘You cannot be the one to tell her. Katja will be back soon, or at least Adam will, and they will be the ones to tell everyone locally.’

I nodded even though I didn’t know for sure what had happened and Penny had already started to walk away in the direction of Ross’s office, running a hand over the brown hair plastered like a cap to her head with sweat.

Diana looked like a ghost as I turned to her, tone blaring from the upturned phone lying in her lap.

‘Ali had to be resuscitated,’ she breathed, as if whispering somehow might make it a rumour rather than a fact. ‘They’ve got him back, apparently, but only just. He’s still critical with almost certain brain damage.’

My hand flew to my mouth.

‘But they think Kris is going to be OK. He lost a whole lot of blood but ultimately the bullet just took a chunk off the top of his head.’

I grabbed her chair with my other arm to keep myself upright.

‘He’s luckier than a cat, that guy,’ she continued, turning the handset over and over in her lap. ‘But … oh God. Ali has a family – why else would he do it if not to support them all?’

Blood ran as I blinked furiously at the red phone, motionless and expectant on its bed of old newspaper. At that moment, the only answer I had to this particular question was definitely not the right one.

Chapter 2

Reward

There was always sand in the air in Baghdad. It made it easy to pretend nothing ever bothered you except the weather. There had been a gusty great haboob the day before. So he hadn’t even needed to pretend as Katja raged – there was nothing she hadn’t seen, there was nowhere she hadn’t been, and never had she had it as hard as this.

There was no real journalism to be done in this Second Gulf War. Actually, wait, there was plenty to be done, but none that they were going to get away with, thanks to the military and its preposterous miles of red tape, locking every square inch of the battlefield into a single viewpoint – theirs. He’d been able to rub his eyes all he liked, watching smoke wreathing around her head, ash dropping all over the place from the cigarette in her hand that she was too busy using to point her nicotine-stained finger of blame rather than actually inhale. Kris should have taken more responsibility for himself. Did he honestly need her to keep telling him the stakes were higher than they’d ever been? This was Baghdad at the peak of the conflict, the crest of the West’s magnanimous takeover in the Middle East! They were in constant competition with every other news network on the ground in Iraq for the mealiest amount of access. There was no excuse good enough for not being in the right place at the right time. Was someone with a reputation like hers going to let the network fall behind on the next stage of this war because of a dated piece of paperwork? As if she could ever use something as trivial as an incorrect ID badge in her defence. He should have known the expiry date on his press pass as well as he knew his own fucking birthday.

There she had paused, just for a moment, mosaic of lines round her black eyes softening as she reassured him – she thought she knew he was as frustrated as she was. As if changing tack was going to help him open his mouth with all that sand still in the air, gluing his throat fast shut.

For they both knew this war was stage-managed like none other. They both knew that moving around this tortured city, once the pearl of the Middle East, now patchworked with roadblocks, was down to the military and its piles of admin. Making it the wrong side of dangerous for journalists to operate without military cover was both deliberate and deniable. Hell, they were even calling it embedding, as if appropriating a verb that suggested reporters and soldiers were actually getting into bed with each other would make any result the unvarnished, objective truth. Forget about how they’d got the job done in a gazillion other warzones. These were the new rules of engagement. 9/11 had changed everything. They’d been around the block together for years, hadn’t they? Kris and Katja, the king and the queen, only together will the network reign supreme?

But still the sand had lingered as he gulped and blinked at her, wound so tight in her customary black knits that she may as well have been another incoming tornado herself.

Because it was never Katja staring down a lens at kids dying in the street, zooming in on the miniature sandals torn from their little feet, white-balancing on the pages of their schoolbooks flaming on the pavement. It was never Katja bolting towards the fear while everyone else bolted away. Hanging around for just one more shot – the twisted wheelchair, the splintered walking stick, the destroyed remnants of everyday life that really brought it home. The pictures that were worth the risk, that made people choke on their morning coffee. The images that made those in power sit up, listen, and hopefully change the record. Photographs and video of places normal folks only knew existed because Kris was the one who had taken them. Because Kris was the one who’d looked them in the eye so they didn’t have to.

The fields of skulls. The vulture waiting patiently for the baby to die. The man’s head sticking out of a flaming tyre – necklaced, they called it, as if doing something so unimaginable to another human being should ever transcend to being an actual verb.

And by the time the fireworks started in Baghdad it was only ever Andie’s hand at his back – making sure he didn’t fall, shielding him from crowds, projectiles, whatever else she could see that he couldn’t because he was too busy looking down the viewfinder. By then, Andie was his eyes. Katja had given up long ago. Katja, everybody’s, yet nobody’s, mother. Kris fingered the outline of the passport stashed in its usual zipped cargo pocket, staring at the featureless English countryside blurring beyond the taxi window as the traffic inched along the motorway. Maybe that was why she couldn’t admit she should have remembered his fucking birthday too.

They’d all known for a few days that the airport road was hot. Why else would they all have been benched, ordered not to leave the office under any circumstances, when every news network in the world was desperate to outdo the other on the biggest story in town? You had to travel that thing to get anywhere relevant in Baghdad. And the lot of them had the tip off – it was the same intelligence report doing the rounds. It wasn’t as if each news outfit in place occupied a different corner of the city. They were all living in the same street, locked in together in the same fortified houses, behind the same so-called rings of steel. They all partied with each other, even though at home they were kept in their opposing corners. Out where it mattered, where they were the only ones doing the real work, they were all in it together, enemies closer than friends. The local militia had clocked how Western journalists travelled from the start – their armoured cars may as well have been strippers, wearing smaller bikinis every time. If you were a trigger-happy militiaman, you could always bet on an armoured car on the airport road – the only highway in the place that linked anything of note as far as the invasion was concerned. They may as well have named it the Red Zone alongside their so-called Green. That highway just spelled out ‘More Idiots Coming into Baghdad’. The definition of an easy target, if you wanted to have a pop. And as soon as Katja sent the intel up to top brass, that was it. House arrest. Locked up by both sides.

It had been a late one, the night before, as usual. Everyone was grouchy, too many people with no place to go, again. Pack a locked room full of folks kept from doing the single thing they know how to, and it will only ever end at the bottom of a bottle of turps. And still there was no such thing as an early night in the sandpit. If Kris wasn’t lining up the camera for whichever Tom, Dick or Harry that the news network had parachuted into position to repeat the same thing into the microphone hour after hour after hour, then he’d be editing video he hadn’t shot himself because it was getting more and more dangerous for anyone to move around.

He’d known the intel was about a kidnap threat too, of course he had. As if all he ever cared about was his camera, as if his eye alone couldn’t possibly compute the bigger picture, the one he wasn’t directly looking at. This was hardly his first rodeo. He’d covered the First Gulf War for as long as Katja, never mind that he wasn’t the one giving the orders, only carrying them out. It didn’t take a genius to figure out what the intelligence report actually said. It wouldn’t have made sense otherwise. It had to be about Westerners specifically, pinpointing times and locations for an ambush, and not just another load of tribal pop shots. At some point, this frenzy of power and bloodshed had to count for more than just another few bodies.

So Kris had known perfectly well they shouldn’t have gone out that day. The reward was nowhere near worth it. He could take a guess at how much pressure Katja was under, but no one was asking for his opinion. No one ever did. And to think he’s a man who calculates risk more than any of them.

All anyone ever wanted to do was look at his pictures. It seemed no one else could see that every single one was a measure of risk, even in the most banal of locations. Not just because he is in the literal line of fire. Because if his timing isn’t perfect, if his fly doesn’t open and close over his shutter at the exact right nano-second, his whole composition will fall apart, he’ll end up with a completely different picture, and the whole operation will have been a waste of fucking time. Photojournalism allows no time for practice. The perfect shot only presents itself the once. He is calculating, faster than anyone can imagine, before every single frame. So to chance a journey like that for a press pass? An ID badge worth less than the plastic it’s made of if the person in the mugshot is dead? In Baghdad, no less, the heart of the Middle East, where karma was worth a whole lot more than minor detail?

This was a zero-sum game. They knew Westerners were the target. They knew the road was a target. And only paperwork lay at the end. It would never have been his call.

Andie tried reasoning with Katja too, of course she did. He was capable of fighting his own corner but it was her job to do it for him, and she was damn good at it. Besides, the sand was in his eyes, his ears, everywhere by then. He couldn’t speak. He’d opened his mouth, all he’d found was a scream, had to swallow it. No one seemed to care what Kris ever said, only what he saw. As for Andie, this war was going to define reputations for years and this was another opportunity to show how good of an operator she could be, even though people did things for her just because of the way she asked. That was her gift. If they weren’t going to be able to go out and film stories then surely the paperwork could wait another day or two. She even thought there was a way to wrangle a new badge without actually having to go anywhere, using her contacts in Jordan. They’ve seen his mugshot a thousand times, haven’t they, she’d said, trying to make light of it.

Katja’d laughed too, but not in the way Andie wanted. Katja had lost that gift a long time ago. No one ever seemed to clock what was happening when people like them lost the gifts they’d been hired to use.

And then it got worse, Katja insisted he take Ali too, bring along an Arabic speaker just to renew the damn pass. The Americans were the ones they had to sweet-talk to do it, and none of them spoke Arabic. So why risk him too? What hadn’t Kris known about the pressure Katja was really under? For two people who had been so close for so long, how could they have found themselves so far apart they were now opposite? Something else he hadn’t been able to ask her, but the sand couldn’t help with either.

Ali would have walked through fire if they’d asked, he practically already had, there had been so many explosions to film. Katja’d even said it aloud, the tornado curling and tightening as she leant in closer, that Ali would minimise any threat against him just by looking the part. Never mind that both his cameras, which had to go everywhere he went just in case Saddam Hussein himself walked in, were going to look as inoffensive as a fucking chihuahua in a handbag.

So the sand became grit that he had to keep blinking away. His throat closed over, the argument stayed stuck. Katja was going to make them do it. She was going to send them all out anyway, just to keep his paperwork clean.

For her, the risk of being caught short was far worse than any risk he was about to take. For her, the reward was worth it.

All he remembers after that is being sent home. Packed on a plane like registered post and just … sent home. As if Lucia and the kids would suddenly make it all go away.

Chapter 3

Hero’s Welcome

It was a week later, at least I think it was. Overnight shifts had a habit of making you lose all sense of time and place. It would have been worse if Diana and I weren’t always on together. At least for us, there was always someone else in an identical position – even better, someone we’d known for years. Di and I had been closer than sisters at boarding school. There was always an untold classroom story we could dredge up during the dead hours before dawn. And the chances were that one of us would be on form even if the other one wasn’t. The truth is it was always her. She could take things in her stride in a way I never could.