IMirror

of Fashion,Admiral

of Finance,Don't,

in a passion,Denounce

this poor Romance;For,

while I dare not hope it mightEnthuse

you,Perhaps it

will, some rainy night,Amuse

you.IISo,

your attention,In

poetry polite,To my

inventionI

bashfully invite.Don't

hurl the book at Eddie's headDeep

laden,Or

Messmore's; you might hit insteadWill

Braden.IIIKahn

among Canners,And

Grand Vizier of style,Emir

of Manners,Accept—and

place on file—This

tribute, which I proffer whileI

grovel,And honor

with thy matchless SmileMy

novel.

CHAPTER I

THE

YEZIDEEOnly

when the Nan-yang

Maru sailed from

Yuen-San did her terrible sense of foreboding begin to subside.For

four years, waking or sleeping, the awful subconsciousness of supreme

evil had never left her.But

now, as the Korean shore, receding into darkness, grew dimmer and

dimmer, fear subsided and grew vague as the half-forgotten memory of

horror in a dream.She

stood near the steamer's stern apart from other passengers, a

slender, lonely figure in her silver-fox furs, her ulster and smart

little hat, watching the lights of Yuen-San grow paler and smaller

along the horizon until they looked like a level row of stars.Under

her haunted eyes Asia was slowly dissolving to a streak of vapour in

the misty lustre of the moon.Suddenly

the ancient continent disappeared, washed out by a wave against the

sky; and with it vanished the last shreds of that accursed nightmare

which had possessed her for four endless years. But whether during

those unreal years her soul had only been held in bondage, or

whether, as she had been taught, it had been irrevocably destroyed,

she still remained uncertain, knowing nothing about the death of

souls or how it was accomplished.As

she stood there, her sad eyes fixed on the misty East, a passenger

passing—an Englishwoman—paused to say something kind to the young

American; and added, "if there is anything my husband and I can

do it would give us much pleasure." The girl had turned her head

as though not comprehending. The other woman hesitated."This

is Doctor Norne's daughter, is it not?" she inquired in a

pleasant voice."Yes,

I am Tressa Norne.... I ask your pardon.... Thank you, madam:—I

am—I seem to be—a trifle dazed——""What

wonder, you poor child! Come to us if you feel need of

companionship.""You

are very kind.... I seem to wish to be alone, somehow.""I

understand.... Good-night, my dear."Late

the next morning Tressa Norne awoke, conscious for the first time in

four years that it was at last her own familiar self stretched out

there on the pillows where sunshine streamed through the porthole.

All that day she lay in her bamboo steamer chair on deck. Sun and

wind conspired to dry every tear that wet her closed lashes. Her

dark, glossy hair blew about her face; scarlet tinted her full lips

again; the tense hands relaxed. Peace came at sundown.That

evening she took her Yu-kin from her cabin and found a chair on the

deserted hurricane deck.And

here, in the brilliant moonlight of the China Sea, she curled up

cross-legged on the deck, all alone, and sounded the four futile

strings of her moon-lute, and hummed to herself, in a still voice,

old songs she had sung in Yian before the tragedy. She sang the

tent-song called

Tchinguiz. She sang

Camel Bells and

The Blue Bazaar,—children's

songs of the Yiort. She sang the ancient Khiounnou song called "The

Saghalien":IIn

the month of SaffarAmong

the river-reedsI

saw two horsemenSitting

on their steeds.Tulugum!Heitulum!By

the river-reedsIIIn

the month of SaffarA

demon guards the ford.Tokhta,

my Lover!Draw

your shining sword!Tulugum!Heitulum!Slay

him with your sword!IIIIn

the month of SaffarAmong

the water-weedsI

saw two horsemenFighting

on their steeds.Tulugum!Heitulum!How

my lover bleeds!IVIn

the month of Saffar,The

Year I should have wed—The

Year of The Panther—My

lover lay dead,—Tulugum!Heitulum!Dead

without a head.And

songs like these—the one called "Keuke Mongol," and an

ancient air of the Tchortchas called "The Thirty Thousand

Calamities," and some Chinese boatmen's songs which she had

heard in Yian before the tragedy; these she hummed to herself there

in the moonlight playing on her round-faced, short-necked lute of

four strings.Terror

indeed seemed ended for her, and in her heart a great overwhelming

joy was welling up which seemed to overflow across the entire moonlit

world.She

had no longer any fear; no premonition of further evil. Among the few

Americans and English aboard, something of her story was already

known. People were kind; and they were also considerate enough to

subdue their sympathetic curiosity when they discovered that this

young American girl shrank from any mention of what had happened to

her during the last four years of the Great World War.It

was evident, also, that she preferred to remain aloof; and this

inclination, when finally understood, was respected by her fellow

passengers. The clever, efficient and polite Japanese officers and

crew of the Nan-yang

Maru were

invariably considerate and courteous to her, and they remained nicely

reticent, although they also knew the main outline of her story and

very much desired to know more. And so, surrounded now by the

friendly security of civilised humanity, Tressa Norne, reborn to

light out of hell's own shadows, awoke from four years of nightmare

which, after all, perhaps, never had seemed entirely actual.And

now God's real sun warmed her by day; His real moon bathed her in

creamy coolness by night; sky and wind and wave thrilled her with

their blessed assurance that this was once more the real world which

stretched illimitably on every side from horizon to horizon; and the

fair faces and pleasant voices of her own countrymen made the past

seem only a ghastly dream that never again could enmesh her soul with

its web of sorcery.And

now the days at sea fled very swiftly; and when at last the Golden

Gate was not far away she had finally managed to persuade herself

that nothing really can harm the human soul; that the monstrous

devil-years were ended, never again to return; that in this vast,

clean Western Continent there could be no occult threat to dread, no

gigantic menace to destroy her body, no secret power that could

consign her soul to the dreadful abysm of spiritual annihilation.Very

early that morning she came on deck. The November day was

delightfully warm, the air clear save for a belt of mist low on the

water to the southward.She

had been told that land would not be sighted for twenty-four hours,

but she went forward and stood beside the starboard rail, searching

the horizon with the enchanted eyes of hope.As

she stood there a Japanese ship's officer crossing the deck, forward,

halted abruptly and stood staring at something to the southward.At

the same moment, above the belt of mist on the water, and perfectly

clear against the blue sky above, the girl saw a fountain of gold

fire rise from the fog, drift upward in the daylight, slowly assume

the incandescent outline of a serpentine creature which leisurely

uncoiled and hung there floating, its lizard-tail undulating, its

feet with their five stumpy claws closing, relaxing, like those of a

living reptile. For a full minute this amazing shape of fire floated

there in the sky, brilliant in the morning light, then the reptilian

form faded, died out, and the last spark vanished in the sunshine.When

the Japanese officer at last turned to resume his promenade, he

noticed a white-faced girl gripping a stanchion behind him as though

she were on the point of swooning. He crossed the deck quickly.

Tressa Norne's eyes opened."Are

you ill, Miss Norne?" he asked."The—the

Dragon," she whispered.The

officer laughed. "Why, that was nothing but Chinese

day-fireworks," he explained. "The crew of some fishing

boat yonder in the fog is amusing itself." He looked at her

narrowly, then with a nice little bow and smile he offered his arm:

"If you are indisposed, perhaps you might wish to go below to

your stateroom, Miss Norne?"She

thanked him, managed to pull herself together and force a ghost of a

smile.He

lingered a moment, said something cheerful about being nearly home,

then made her a punctilious salute and went his way.Tressa

Norne leaned back against the stanchion and closed her eyes. Her

pallor became deathly. She bent over and laid her white face in her

folded arms.After

a while she lifted her head, and, turning very slowly, stared at the

fog-belt out of frightened eyes.And

saw, rising out of the fog, a pearl-tinted sphere which gradually

mounted into the clear daylight above like the full moon's phantom in

the sky.Higher,

higher rose the spectral moon until at last it swam in the very

zenith. Then it slowly evaporated in the blue vault above.A

great wave of despair swept her; she clung to the stanchion, staring

with half-blinded eyes at the flat fog-bank in the south.But

no more "Chinese day-fireworks" rose out of it. And at

length she summoned sufficient strength to go below to her cabin and

lie there, half senseless, huddled on her bed.When

land was sighted, the following morning, Tressa Norne had lived a

century in twenty-four hours. And in that space of time her agonised

soul had touched all depths.But

now as the Golden Gate loomed up in the morning light, rage, terror,

despair had burned themselves out. From their ashes within her mind

arose the cool wrath of desperation armed for anything, wary, alert,

passionately determined to survive at whatever cost, recklessly ready

to fight for bodily existence.That

was her sole instinct now, to go on living, to survive, no matter at

what price. And if it were indeed true that her soul had been slain,

she defied its murderers to slay her body also.That

night, at her hotel in San Francisco, she double-locked her door and

lay down without undressing, leaving all lights burning and an

automatic pistol underneath her pillow.Toward

morning she fell asleep, slept for an hour, started up in awful fear.

And saw the double-locked door opposite the foot of her bed slowly

opening of its own accord.Into

the brightly illuminated room stepped a graceful young man in full

evening dress carrying over his left arm an overcoat, and in his

other hand a top hat and silver tipped walking-stick.With

one bound the girl swung herself from the bed to the carpet and

clutched at the pistol under her pillow."Sanang!"

she cried in a terrible voice."Keuke

Mongol!" he said, smilingly.For

a moment they confronted each other in the brightly lighted bedroom,

then, partly turning, he cast a calm glance at the open door behind

him; and, as though moved by a wind, the door slowly closed. And she

heard the key turn of itself in the lock, and saw the bolt slide

smoothly into place again.Her

power of speech came back to her presently—only a broken whisper at

first: "Do you think I am afraid of your accursed magic?"

she managed to gasp. "Do you think I am afraid of you, Sanang?""You

are afraid," he said serenely."You

lie!""No,

I do not lie. To one another the Yezidees never lie.""You

lie again, assassin! I am no Yezidee!"He

smiled gently. His features were pleasing, smooth, and regular; his

cheek-bones high, his skin fine and of a pale and delicate ivory

colour. Once his black, beautifully shaped eyes wandered to the

levelled pistol which she now held clutched desperately close to her

right hip, and a slightly ironical expression veiled his gaze for an

instant."Bullets?"

he murmured. "But you and I are of the Hassanis.""The

third lie, Sanang!" Her voice had regained its strength. Tense,

alert, blue eyes ablaze, every faculty concentrated on the terrible

business before her, the girl now seemed like some supple leopardess

poised on the swift verge of murder."Tokhta!"[1]

She spat the word. "Any movement toward a hidden weapon, any

gesture suggesting recourse to magic—and I kill you, Sanang,

exactly where you stand!""With

a pistol?" He laughed. Then his smooth features altered subtly.

He said: "Keuke Mongol, who call yourself Tressa

Norne,—Keuke—heavenly azure-blue,—named so in the temple

because of the colour of your eyes—listen attentively, for this is

the Yarlig which I bring to you by word of mouth from Yian, as from

Yezidee to Yezidee:"Here,

in this land called the United States of America, the Temple girl,

Keuke Mongol, who has witnessed the mysteries of Erlik and who

understands the magic of the Sheiks-el-Djebel, and who has seen Mount

Alamout and the eight castles and the fifty thousand Hassanis in

white turbans and in robes of white;—you—Azure-blue

eyes—heed the Yarlig!—or may thirty thousand calamities overtake

you!"There

was a dead silence; then he went on seriously: "It is decreed:

You shall cease to remember that you are a Yezidee, that you are of

the Hassanis, that you ever have laid eyes on Yian the Beautiful,

that you ever set naked foot upon Mount Alamout. It is decreed that

you remember nothing of what you have seen and heard, of what has

been told and taught during the last four years reckoned as the

Christians reckon from our Year of the Bull. Otherwise—my Master

sends you this for your—convenience."Leisurely,

from under his folded overcoat, the young man produced a roll of

white cloth and dropped it at her feet and the girl shrank aside,

shuddering, knowing that the roll of white cloth was meant for her

winding-sheet.Then

the colour came back to lip and cheek; and, glancing up from the soft

white shroud, she smiled at the young man: "Have you ended your

Oriental mummery?" she asked calmly. "Listen very seriously

in your turn, Sanang, Sheik-el-Djebel, Prince of the Hassanis who,

God knows when and how, have come out into the sunshine of this clean

and decent country, out of a filthy darkness where devils and

sorcerers make earth a hell."If

you, or yours, threaten me, annoy me, interfere with me, I shall go

to our civilised police and tell all I know concerning the Yezidees.

I mean to live. Do you understand? You know what you have done to me

and mine. I come back to my own country alone, without any living

kin, poor, homeless, friendless,—and, perhaps, damned. I intend,

nevertheless, to survive. I shall not relax my clutch on bodily

existence whatever the Yezidees may pretend to have done to my soul.

I am determined to live in the body, anyway."He

nodded gravely.She

said: "Out at sea, over the fog, I saw the sign of Yu-lao in

fire floating in the day-sky. I saw his spectral moon rise and vanish

in mid-heaven. I understood. But——" And here she suddenly

showed an edge of teeth under the full scarlet upper lip: "Keep

your signs and your shrouds to yourself, dog of a

Yezidee!—toad!—tortoise-egg!—he-goat with three legs! Keep your

threats and your messages to yourself! Keep your accursed magic to

yourself! Do you think to frighten me with your sorcery by showing me

the Moons of Yu-lao?—by opening a bolted door? I know more of such

magic than do you, Sanang—Death Adder of Alamout!"Suddenly

she laughed aloud at him—laughed insultingly in his expressionless

face:"I

saw you and Gutchlug Khan and your cowardly Tchortchas in

red-lacquered jackets slink out of the Temple of Erlik where the

bronze gong thundered and a cloud settled down raining little yellow

snakes all over the marble steps—all over you, Prince Sanang! You

were afraid,

my Tougtchi!—you and Gutchlug and your red Tchortchas with their

halberds all dripping with human entrails! And I saw you mount and

gallop off into the woods while in the depths of the magic cloud

which rained little yellow snakes all around you, we temple girls

laughed and mocked at you—at you and your cowardly Tchortcha

horsemen."A

slight tinge of pink came into the young man's pale face. Tressa

Norne stepped nearer, her levelled pistol resting on her hip."Why

did you not complain of us to your Master, the Old Man of the

Mountain?" she asked jeeringly. "And where, also, was your

Yezidee magic when it rained little snakes?—What frightened you

away—who had boldly come to seize a temple girl—you who had

screwed up your courage sufficiently to defy Erlik in his very shrine

and snatch from his temple a young thing whose naked body wrapped in

gold was worth the chance of death to you?"The

young man's top-hat dropped to the floor. He bent over to pick it up.

His face was quite expressionless, quite colourless, now."I

went on no such errand," he said with an effort. "I went

with a thousand prayers on scarlet paper made in——""A

lie, Yezidee! You came to seize

me!"He

turned still paler. "By Abu, Omar, Otman, and Ali, it is not

true!""You

lie!—by the Lion of God, Hassini!"She

stepped closer. "And I'll tell you another thing you fear—you

Yezidee of Alamout—you robber of Yian—you sorcerer of Sabbah

Khan, and chief of his sect of Assassins! You fear this native land

of mine, America; and its laws and customs, and its clear, clean

sunshine; and its cities and people; and its police! Take that

message back. We Americans fear nobody save the true

God!—nobody—neither Yezidee nor Hassani nor Russ nor German nor

that sexless monster born of hell and called the Bolshevik!""Tokhta!"

he cried sharply."Damn

you!" retorted the girl; "get out of my room! Get out of my

sight! Get out of my path! Get out of my life! Take that to your

Master of Mount Alamout! I do what I please; I go where I please; I

live as I please. And if I please,

I turn against him!""In

that event," he said hoarsely, "there lies your

winding-sheet on the floor at your feet! Take up your shroud; and

make Erlik seize you!""Sanang,"

she said very seriously."I

hear you, Keuke-Mongol.""Listen

attentively. I wish to live. I have had enough of death in life. I

desire to remain a living, breathing thing—even if it be true—as

you Yezidees tell me, that you have caught my soul in a net and that

your sorcerers really control its destiny."But

damned or not, I passionately desire to live. And I am coward enough

to hold my peace for the sake of living. So—I remain silent. I have

no stomach to defy the Yezidees; because, if I do, sooner or later I

shall be killed. I know it. I have no desire to die for others—to

perish for the sake of the common good. I am young. I have suffered

too much; I am determined to live—and let my soul take its chances

between God and Erlik."She

came close to him, looked curiously into his pale face."I

laughed at you out of the temple cloud," she said. "I know

how to open bolted doors as well as you do. And I know

other things. And

if you ever again come to me in this life I shall first torture you,

then slay you. Then I shall tell all!... and unroll my shroud.""I

keep your word of promise until you break it," he interrupted

hastily. "Yarlig! It is decreed!" And then he slowly turned

as though to glance over his shoulder at the locked and bolted door."Permit

me to open it for you, Prince Sanang," said the girl scornfully.

And she gazed steadily at the door.Presently,

all by itself, the key turned in the lock, the bolt slid back, the

door gently opened.Toward

it, white as a corpse, his overcoat on his left arm, his stick and

top-hat in the other hand, crept the young man in his faultless

evening garb.Then,

as he reached the threshold, he suddenly sprang aside. A small yellow

snake lay coiled there on the door sill. For a full throbbing minute

the young man stared at the yellow reptile in unfeigned horror. Then,

very cautiously, he moved his fascinated eyes sideways and gazed in

silence at Tressa Norne.The

girl laughed."Sorceress!"

he burst out hoarsely. "Take that accursed thing from my path!""What

thing, Sanang?" At that his dark, frightened eyes stole toward

the threshold again, seeking the little snake. But there was no snake

there. And when he was certain of this he went, twitching and

trembling all over.Behind

him the door closed softly, locking and bolting itself.And

behind the bolted door in the brightly lighted bedroom Tressa Norne

fell on both knees, her pistol still clutched in her right hand,

calling passionately upon Christ to forgive her for the dreadful

ability she had dared to use, and begging Him to save her body from

death and her soul from the snare of the Yezidee.

CHAPTER II

THE

YELLOW SNAKEWhen

the young man named Sanang left the bed-chamber of Tressa Norne he

turned to the right in the carpeted corridor outside and hurried

toward the hotel elevator. But he did not ring for the lift; instead

he took the spiral iron stairway which circled it, and mounted

hastily to the floor above.Here

was his own apartment and he entered it with a key bearing the hotel

tag. A dusky-skinned powerful old man wearing a grizzled beard and a

greasy broadcloth coat of old-fashioned cut known to provincials as a

"Prince Albert" looked up from where he was seated

cross-legged upon the sofa, sharpening a curved knife on a whetstone."Gutchlug,"

stammered Sanang, "I am afraid of her! What happened two years

ago at the temple happened again a moment since, there in her very

bedroom! She made a yellow death-adder out of nothing and placed it

upon the threshold, and mocked me with laughter. May Thirty Thousand

Calamities overtake her! May Erlik seize her! May her eyes rot out

and her limbs fester! May the seven score and three principal

devils——""You

chatter like a temple ape," said Gutchlug tranquilly. "Does

Keuke Mongol die or live? That alone interests me.""Gutchlug,"

faltered the young man, "thou knowest that m-my heart is

inclined to mercy toward this young Yezidee——""I

know that it is inclined to lust," said the other bluntly.Sanang's

pale face flamed."Listen,"

he said. "If I had not loved her better than life had I dared go

that day to the temple to take her for my own?""You

loved life better," said Gutchlug. "You fled when it rained

snakes on the temple steps—you and your Tchortcha horsemen! Kai! I

also ran. But I gave every soldier thirty blows with a stick before I

slept that night. And you should have had your thirty, also,

conforming to the Yarlig, my Tougtchi."Sanang,

still holding his hat and cane and carrying his overcoat over his

left arm, looked down at the heavy, brutal features of Gutchlug

Khan—at the cruel mouth with its crooked smile under the grizzled

beard; at the huge hands—the powerful hands of a murderer—now

deftly honing to a razor-edge the Kalmuck knife held so firmly yet

lightly in his great blunt fingers."Listen

attentively, Prince Sanang," growled Gutchlug, pausing in his

monotonous task to test the blade's edge on his thumb—"Does

the Yezidee Keuke Mongol live? Yes or no?"Sanang

hesitated, moistened his pallid lips. "She dares not betray us.""By

what pledge?""Fear.""That

is no pledge. You also were afraid, yet you went to the temple!""She

has listened to the Yarlig. She has looked upon her shroud. She has

admitted that she desires to live. Therein lies her pledge to us.""And

she placed a yellow snake at your feet!" sneered Gutchlug.

"Prince Sanang, tell me, what man or what devil in all the

chronicles of the past has ever tamed a Snow-Leopard?" And he

continued to hone his yataghan."Gutchlug——""No,

she dies," said the other tranquilly."Not

yet!""When,

then?""Gutchlug,

thou knowest me. Hear my pledge! At her first gesture toward

treachery—her first thought of betrayal—I myself will end it

all.""You

promise to slay this young snow-leopardess?""By

the four companions, I swear to kill her with my own hands!"Gutchlug

sneered. "Kill her—yes—with the kiss that has burned thy

lips to ashes for all these months. I know thee, Sanang. Leave her to

me. Dead she will no longer trouble thee.""Gutchlug!""I

hear, Prince Sanang.""Strike

when I nod. Not until then.""I

hear, Tougtchi. I understand thee, my Banneret. I whet my knife.

Kai!"Sanang

looked at him, put on his top-hat and overcoat, pulled on a pair of

white evening gloves."I

go forth," he said more pleasantly."I

remain here to talk to my seven ancestors and sharpen my knife,"

remarked Gutchlug."When

the white world and the yellow world and the brown world and the

black world finally fall before the Hassanis," said Sanang with

a quick smile, "I shall bring thee to her. Gutchlug—once—before

she is veiled, thou shalt behold what is lovelier than Eve."The

other stolidly whetted his knife.Sanang

pulled out a gold cigarette case, lighted a cigarette with an air."I

go among Germans," he volunteered amiably. "The huns swam

across two oceans, but, like the unclean swine, it is their own

throats they cut when they swim! Well, there is only one God. And not

very many angels. Erlik is greater. And there are many million devils

to do his bidding. Adieu. There is rice and there is koumiss in the

frozen closet. When I return you shall have been asleep for hours."When

Sanang left the hotel one of two young men seated in the hotel lobby

got up and strolled out after him.A

few minutes later the other man went to the elevator, ascended to the

fourth floor, and entered an apartment next to the one occupied by

Sanang.There

was another man there, lying on the lounge and smoking a cigar.

Without a word, they both went leisurely about the matter of

disrobing for the night.When

the shorter man who had been in the apartment when the other entered,

and who was dark and curly-headed, had attired himself in pyjamas, he

sat down on one of the twin beds to enjoy his cigar to the bitter

end."Has

Sanang gone out?" he inquired in a low voice."Yes.

Benton went after him."The

other man nodded. "Cleves," he said, "I guess it looks

as though this Norne girl is in it, too.""What

happened?""As

soon as she arrived, Sanang made straight for her apartment. He

remained inside for half an hour. Then he came out in a hurry and

went to his own rooms, where that surly servant of his squats all

day, shining up his arsenal, and drinking koumiss.""Did

you get their conversation?""I've

got a record of the gibberish. It requires an interpreter, of

course.""I

suppose so. I'll take the records east with me to-morrow, and by the

same token I'd better notify New York that I'm leaving."He

went, half-undressed, to the telephone, got the telegraph office, and

sent the following message:"Recklow,

New York:"Leaving

to-morrow for N. Y. with samples. Retain expert in Oriental fabrics."Victor

Cleves.""Report

for me, too," said the dark young man, who was still enjoying

his cigar on his pillows.So

Cleves sent another telegram, directed also to"Recklow,

New York:"Benton

and I are watching the market. Chinese importations fluctuate. Recent

consignment per

Nan-yang Maru will

be carefully inspected and details forwarded."Alek

Selden."In

the next room Gutchlug could hear the voice of Cleves at the

telephone, but he merely shrugged his heavy shoulders in contempt.

For he had other things to do beside eavesdropping.Also,

for the last hour—in fact, ever since Sanang's departure—something

had been happening to him—something that happens to a Hassani only

once in a lifetime. And now this unique thing had happened to him—to

him, Gutchlug Khan—to him before whose Khiounnou ancestors

eighty-one thousand nations had bowed the knee.It

had come to him at last, this dread thing, unheralded, totally

unexpected, a few minutes after Sanang had departed.And

he suddenly knew he was going to die.And,

when, presently, he comprehended it, he bent his grizzled head and

listened seriously. And, after a little silence, he heard his soul

bidding him farewell.So

the chatter of white men at a telephone in the next apartment had no

longer any significance for him. Whether or not they had been spying

on him; whether they were plotting, made no difference to him now.He

tested his knife's edge with his thumb and listened gravely to his

soul bidding him farewell.But,

for a Yezidee, there was still a little detail to attend to before

his soul departed;—two matters to regulate. One was to select his

shroud. The other was to cut the white throat of this young

snow-leopardess called Keuke Mongol, the Yezidee temple girl.And

he could steal down to her bedroom and finish that matter in five

minutes.But

first he must choose his shroud, as is the custom of the Yezidee.That

office, however, was quickly accomplished in a country where fine

white sheets of linen are to be found on every hotel bed.So,

on his way to the door, his naked knife in his right hand, he paused

to fumble under the bed-covers and draw out a white linen sheet.Something

hurt his hand like a needle. He moved it, felt the thing squirm under

his fingers and pierce his palm again and again. With a shriek, he

tore the bedclothes from the bed.A

little yellow snake lay coiled there.He

got as far as the telephone, but could not use it. And there he fell

heavily, shaking the room and dragging the instrument down with him.There

was some excitement. Cleves and Selden in their bathrobes went in to

look at the body. The hotel physician diagnosed it as heart-trouble.

Or, possibly, poison. Some gazed significantly at the naked knife

still clutched in the dead man's hands.Around

the wrist of the other hand was twisted a pliable gold bracelet

representing a little snake. It had real emeralds for eyes.It

had not been there when Gutchlug died.But

nobody except Sanang could know that. And later when Sanang came back

and found Gutchlug very dead on the bed and a policeman sitting

outside, he offered no information concerning the new bracelet shaped

like a snake with real emeralds for eyes, which adorned the dead

man's left wrist.Toward

evening, however, after an autopsy had confirmed the house

physician's diagnosis that heart-disease had finished Gutchlug,

Sanang mustered enough courage to go to the desk in the lobby and

send up his card to Miss Norne.It

appeared, however, that Miss Norne had left for Chicago about noon.

CHAPTER III

GREY

MAGIC

To Victor Cleves came the

following telegram in code:

"Washington"April 14th, 1919."

"Investigation ordered by the State Department as the

result of frequent mention in despatches of Chinese troops

operating with the Russian Bolsheviki forces has disclosed that the

Bolsheviki are actually raising a Chinese division of 30,000 men

recruited in Central Asia. This division has been guilty of the

greatest cruelties. A strange rumour prevails among the Allied

forces at Archangel that this Chinese division is led by Yezidee

and Hassani officers belonging to the sect of devil-worshipers and

that they employ black arts and magic in battle.

"From

information so far gathered by the several branches of the United

States Secret Service operating throughout the world, it appears

possible that the various revolutionary forces of disorder, in

Europe and Asia, which now are violently threatening the peace and

security, of all established civilisation on earth, may have had a

common origin. This origin, it is now suspected, may date back to a

very remote epoch; the wide-spread forces of violence and merciless

destruction may have had their beginning among some ancient and

predatory race whose existence was maintained solely by robbery and

murder.

"Anarchists,

terrorists, Bolshevists, Reds of all shades and degrees, are now

believed to represent in modern times what perhaps once was a tribe

of Assassins—a sect whose religion was founded upon a common

predilection for crimes of violence.

"On this

theory then, for the present, the United States Government will

proceed with this investigation of Bolshevism; and the Secret

Service will continue to pay particular attention to all Orientals

in the United States and other countries. You personally are

formally instructed to keep in touch with XLY-371 (Alek Selden) and

ZB-303 (James Benton), and to employ every possible means to become

friendly with the girl Tressa Norne, win her confidence, and, if

possible, enlist her actively in the Government Service as your

particular aid and comrade.

"It is

equally important that the movements of the Oriental, called

Sanang, be carefully observed in order to discover the identity and

whereabouts of his companions. However, until further instructions

he is not to be taken into custody. M. H. 2479.

"(Signed)"(John Recklow.)"

The long despatch from John

Recklow made Cleves's duty plain enough.

For months, now, Selden and

Benton had been watching Tressa Norne. And they had learned

practically nothing about her.

And now the girl had come

within Cleves's sphere of operation. She had been in New York for

two weeks. Telegrams from Benton in Chicago, and from Selden in

Buffalo, had prepared him for her arrival.

He had his men watching her

boarding-house on West Twenty-eighth Street, men to follow her, men

to keep their eyes on her at the theatre, where every evening, at

10:45, herentr' actewas

staged. He knew where to get her. But he, himself, had been on the

watch for the man Sanang; and had failed to find the slightest

trace of him in New York, although warned that he had

arrived.

So, for that evening, he left

the hunt for Sanang to others, put on his evening clothes, and

dined with fashionable friends at the Patroons' Club, who never for

an instant suspected that young Victor Cleves was in the Service of

the United States Government. About half-past nine he strolled

around to the theatre, desiring to miss as much as possible of the

popular show without being too late to see the curious

littleentr' actein which this

girl, Tressa Norne, appeared alone.

He had secured an aisle seat

near the stage at an outrageous price; the main show was still

thundering and fizzing and glittering as he entered the theatre; so

he stood in the rear behind the orchestra until the descending

curtain extinguished the outrageous glare and din.

Then he went down the aisle,

and as he seated himself Tressa Norne stepped from the wings and

stood before the lowered curtain facing an expectant but oddly

undemonstrative audience.

The girl worked rapidly,

seriously, and in silence. She seemed a mere child there behind the

footlights, not more than sixteen anyway—her winsome eyes and

wistful lips unspoiled by the world's wisdom.

Yet once or twice the mouth

drooped for a second and the winning eyes darkened to a remoter

blue—the brooding iris hue of far horizons.

She wore the characteristic

tabard of stiff golden tissue and the gold pagoda-shaped headpiece

of a Yezidee temple girl. Her flat, slipper-shaped foot-gear was of

stiff gold, too, and curled upward at the toes.

All this accentuated her

apparent youth. For in face and throat no firmer contours had as

yet modified the soft fullness of immaturity; her limbs were boyish

and frail, and her bosom more undecided still, so that the

embroidered breadth of gold fell flat and straight from her chest

to a few inches above the ankles.

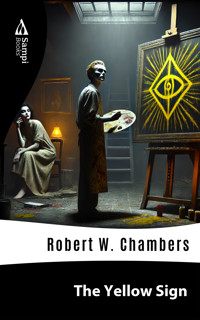

She seemed to have no stock of

paraphernalia with which to aid the performance; no assistant, no

orchestral diversion, nor did she serve herself with any magician's

patter. She did her work close to the footlights.

Behind her loomed a black

curtain; the strip of stage in front was bare even of carpet; the

orchestra remained mute.

But when she needed anything—a

little table, for example—well, it was suddenly there where she

required it—a tripod, for instance, evidently fitted to hold the

big iridescent bubble of glass in which swarmed little tropical

fishes—and which arrived neatly from nowhere. She merely placed her

hands before her as though ready to support something weighty which

she expected and—suddenly, the huge crystal bubble was visible,

resting between her hands. And when she tired of holding it, she

set it upon the empty air and let go of it; and instead of crashing

to the stage with its finny rainbow swarm of swimmers, out of thin

air appeared a tripod to support it.

Applause followed, not very

enthusiastic, for the sort of audience which sustains the shows of

which her performance was merely anentr'

acteis an audience responsive only to the

obvious.

Nobody ever before had seen

that sort of magic in America. People scarcely knew whether or not

they quite liked it. The lightning of innovation stupefies the

dull; ignorance is always suspicious of innovation—always afraid to

put itself on record until its mind is made up by somebody

else.

So in this typical New York

audience approbation was cautious, but every fascinated eye

remained focused on this young girl who continued to do incredible

things, which seemed to resemble "putting something over" on them;

a thing which no uneducated American conglomeration ever quite

forgives.

The girl's silence, too,

perplexed them; they were accustomed to gabble, to noise, to jazz,

vocal and instrumental, to that incessant metropolitan clamour

which fills every second with sound in a city whose only

distinction is its din. Stage, press, art, letters, social

existence unless noisy mean nothing in Gotham; reticence, leisure,

repose are the three lost arts. The megaphone is the city's symbol;

its chiefest crime, silence.

The girl having finished with

the big glass bubble full of tiny fish, picked it up and tossed it

aside. For a moment it apparently floated there in space like a

soap-bubble. Changing rainbow tints waxed and waned on the surface,

growing deeper and more gorgeous until the floating globe glowed

scarlet, then suddenly burst into flame and vanished. And only a

strange, sweet perfume lingered in the air.

But she gave her perplexed

audience no time to wonder; she had seated herself on the stage and

was already swiftly busy unfolding a white veil with which she

presently covered herself, draping it over her like a

tent.

The veil seemed to be

translucent; she was apparently visible seated beneath it. But the

veil turned into smoke, rising into the air in a thin white cloud;

and there, where she had been seated, was a statue of white stone

the image of herself!—in all the frail springtide of early

adolescence—a white statue, cold, opaque, exquisite in its

sculptured immobility.

There came, the next moment, a

sound of distant thunder; flashes lighted the blank curtain; and

suddenly a vein of lightning and a sharper peal shattered the

statue to fragments.