1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

In "The Soul of London," Ford Madox Ford presents a captivating exploration of the city that pulsates with life, culture, and a myriad of human experiences. This work is a masterful blend of impressionistic prose and vivid imagery, drawing on the influence of early 20th-century Modernism. Ford's keen observations of London's urban landscapes, coupled with his lyrical language, provide readers with a vibrant tapestry of the city's social dynamics, architecture, and its ever-changing identity during a time of brisk industrial progress. Through a series of interconnected essays, Ford captures not only the physical but also the spiritual essence of London, making it a seminal piece in urban literature. Ford Madox Ford, a pivotal figure in English literature, was deeply influenced by his own personal experiences and struggles within the turbulent social fabric of early 1900s Britain. His rich literary background, notably his association with the avant-garde literary movement, imbued him with a unique sensibility to reflect on themes of modernity and disillusionment. The intersection of his literary pursuits and experiences in London, intertwined with his friendships with fellow writers, inform the depth and resonance of this work. For those intrigued by the complexities of urban life and the philosophical inquiries it provokes, "The Soul of London" is an essential read. Ford's insights not only illuminate the quintessential spirit of London but also prompt readers to reflect on their own relationship with the cities they inhabit. This book is a profound exploration that transcends time, making it a valuable addition to any literary collection. In this enriched edition, we have carefully created added value for your reading experience: - A succinct Introduction situates the work's timeless appeal and themes. - The Synopsis outlines the central plot, highlighting key developments without spoiling critical twists. - A detailed Historical Context immerses you in the era's events and influences that shaped the writing. - An Author Biography reveals milestones in the author's life, illuminating the personal insights behind the text. - A thorough Analysis dissects symbols, motifs, and character arcs to unearth underlying meanings. - Reflection questions prompt you to engage personally with the work's messages, connecting them to modern life. - Hand‐picked Memorable Quotes shine a spotlight on moments of literary brilliance. - Interactive footnotes clarify unusual references, historical allusions, and archaic phrases for an effortless, more informed read.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

The Soul of London

Table of Contents

Introduction

London, in these pages, becomes a single breathing organism whose countless streets, voices, and memories fuse into a living mind.

The Soul of London by Ford Madox Ford—published in 1905 when he still signed his work Ford Madox Hueffer—is a meditative portrait of the metropolis at the turn of the twentieth century. Neither guidebook nor conventional history, it is a sustained attempt to discern the city’s character, to translate streets and crowds into mood, rhythm, and purpose. Ford brings a novelist’s sensitivity to a nonfiction canvas, tracing how architecture, traffic, and habit shape the inner life of residents. His aim is not to catalogue facts but to understand the atmosphere that binds a vast urban community.

Its classic status rests on the daring of that undertaking and the finesse of its execution. Appearing at a moment when English prose was shedding Victorian certainties, the book helped define a modern way of writing about cities—impressionistic, psychological, and attuned to flux. Readers have long returned to it for a masterclass in how place can be rendered as presence. The book’s influence is felt in later urban portraits that privilege experience over statistics, and it holds a secure place in the lineage linking nineteenth-century city sketches to twentieth-century modernist urban meditations.

Ford wrote against the backdrop of rapid change: expanding suburbs, new technologies, and the pressures of an imperial capital adjusting to modern speed. He registers the novelty without surrendering to spectacle, attentive to the city’s continuities as well as its shocks. By framing London as a palimpsest—layers of time visible in bricks, habits, and routes—he captures the coexistence of heritage and improvisation. His London is not a museum; it is an evolving social organism whose past informs its present temperament. The insight that civic identity arises from the interplay of memory and movement gives the book enduring interpretive power.

The method is observational yet inward: Ford moves through thoroughfares, districts, and daily routines, using sensory impressions to uncover collective psychology. He allows incidental scenes—shopfronts, crossings, stations, doorways—to reveal the underlying discipline and improvisation of urban life. This approach trusts accumulated glimpses to achieve a truthful whole, a mosaic whose pieces shine precisely because they are not forced into argument. The book’s subtitle, A Survey of a Modern City, signals breadth, but the true survey is temperamental: it measures pace, attention, restraint, and desire as they manifest in the forms and frictions of a sprawling metropolis.

Themes emerge gradually and resonate widely: anonymity and neighborliness, fatigue and exhilaration, privacy amid crowding, the ethics of coexistence in shared space. Ford attends to how institutions and habits shape conduct, how the routine of commuting or shopping molds character, how spectacle alternates with restraint. He suggests that a city’s greatness resides not simply in monuments but in the tacit agreements that make daily life possible. The Soul of London is, therefore, also about manners, patience, and the grammar of public space—how people learn to look, wait, and pass, and how these acts accumulate into a civic temperament.

Stylistically, the book exemplifies prose impressionism, a mode Ford championed throughout his career. Sentences layer perception, inference, and memory to approximate the undulations of attention. Rather than march from premise to conclusion, the paragraphs pivot gracefully among observation, association, and reflection, achieving a cadence that feels both spontaneous and considered. This rhythm lends the work its modernity: it invites readers to experience thinking as a form of walking, and walking as a way of thinking. Such technique would become a hallmark of twentieth-century writing about perception, and here it is applied with notable control to the lived complexity of London.

The book’s significance also lies in its author’s broader role in literary culture. Ford later became an influential editor and collaborator, fostering innovations that shaped English-language modernism. The sensibility on display here—curious, exact, receptive to nuance—prefigures the aesthetic he promoted in journals and in his later fiction. While The Soul of London stands independently, its careful listening to the everyday helped clear space for subsequent writers to treat the modern city as a subject worthy of stylistic experiment and philosophical inquiry. Its legacy is less a school than a permission: to feel, to notice, and to render without pedantry.

Key facts clarify the frame. The Soul of London first appeared in 1905, authored by Ford Madox Hueffer, the name Ford used before adopting Ford Madox Ford later in life. It is nonfiction, composed as a reflective survey of London’s character at a historical inflection point. Ford’s purpose is diagnostic and lyrical: to ask what holds the city together and what it asks of those who dwell in it. He avoids exhaustive enumeration in favor of selective episodes that illuminate general truths. The result is both portrait and poetics—a study whose precision arises from fidelity to lived sensation.

Readers approaching the book should expect a city rendered through subtle shifts of focus. The narrative moves among thoroughfares, habits, and types of encounter, pausing where meaning gathers: in the way light cuts a street, in the tacit choreography of pedestrians, in the hush that follows commotion. Ford’s London is outwardly familiar—shops, vehicles, offices—but inwardly distinctive, because he notices what routine makes invisible. The book does not argue a thesis so much as accumulate conviction, and its persuasiveness lies in the recognition it elicits. One sees, after reading, how forms of conduct become forms of thought.

Its status as a classic of urban literature owes to this union of insight and method. The Soul of London retains freshness because it observes without cant and generalizes without haste. It neither idealizes nor condemns; it seeks to understand. Contemporary readers, navigating cities transformed by technology and scale, will find Ford’s questions uncannily current: How does a metropolis shape attention? What bargains of courtesy and self-protection enable coexistence? Where does collective memory reside? The book’s measured curiosity models a way of looking that remains invaluable—patient, precise, humane—especially amid the stimulative overload of modern urban experience.

In sum, The Soul of London offers a lasting meditation on modernity, civility, and place. It portrays the metropolis not as a spectacle to be consumed but as an ethic to be practiced, a shared venture sustained by habits of seeing and restraint. Its themes—continuity and change, solitude and community, order and improvisation—still animate city life. Ford’s prose gives these tensions shape without fixing them in doctrine, allowing readers to project their own streets into his insights. That openness sustains the book’s appeal: it remains a companionable guide to reading a city’s mind—and, by extension, our own.

Synopsis

Ford Madox Ford’s The Soul of London presents an impressionistic survey of the city at the turn of the twentieth century, seeking the collective character that arises from everyday habits rather than monuments or statistics. The book proceeds as a sequence of observational essays, blending anecdote, description, and social reflection. Ford treats London as a living organism whose temperament can be inferred from its streets, institutions, and routines. He avoids exhaustive data, preferring representative scenes and typical experiences. His aim is to identify the city’s underlying tone and manners—its reticence, endurance, and capacity for accommodation—through the cumulative effect of ordinary sights and movements.

The narrative begins with arrivals and first impressions. London’s railway termini, river approaches, and great gates of traffic serve as thresholds to the metropolis. Ford records the gray light, the persistent mist, the smell of coal, and the muted palette of stone and brick. He notes the immediate sense of scale, the subdued yet continuous hum, and the anonymity that surrounds newcomers. Rather than spectacular vistas, the city offers long perspectives of shop fronts and thoroughfares, punctuated by steady crowds. The emphasis falls on atmosphere and motion—the way London makes itself felt through tone and rhythm more than through singular, dramatic scenes.

Ford moves to the streets, where he reads the city’s character in its traffic and comportment. Omnibuses, cabs, and pedestrians establish a pace that is unhurried yet relentless. Advertising hoardings and placards create a chorus of public messages, while constables and street rules keep order with minimal display. The Strand and Fleet Street stand out as conduits of business and talk, their noise disciplined rather than chaotic. Courtesy, reserve, and a preference for compromise shape interactions. From the top of a bus, Ford surveys the city’s surface, treating the everyday journey as a vantage point for understanding London’s quiet steadiness.

The book then addresses work and commerce, concentrating on the City’s routines. Morning brings a tide of clerks and merchants to counting-houses, banks, and exchanges; evening sees their measured retreat. Ford links these movements to wider imperial circuits: docks, warehouses, and shipping bind distant markets to London’s ledger books. He attends to the press in Fleet Street, insurance and finance near the Bank, and the sober energy of trade. The rhythms of office hours, lunch breaks, and closing time illustrate punctuality and reliability as civic virtues. Without dramatizing individual careers, he portrays commerce as a collective discipline that sustains the metropolis.

Leisure receives corresponding attention. Ford surveys the West End’s theaters and music-halls, gentlemen’s clubs, restaurants, and the sociable spaces of promenades and parks. Sundays impose a hush, while Bank Holidays send crowds to commons, riversides, and museums. He remarks on the city’s appetite for steady amusements rather than spectacle: outings to the park, respectable entertainments, and seasonal fairs. Public institutions—galleries, libraries, and exhibitions—serve as both instruction and recreation. The patterns of evening lights, shop windows, and returning traffic complete the daily cycle. Leisure, like work, appears organized and habitual, reinforcing the impression of a city governed by routine and moderation.

Turning to social geography, Ford contrasts districts without sensationalism. Mayfair and Belgravia suggest wealth and ceremony; Bloomsbury signals study and modest comfort; Chelsea represents a tasteful bohemia. The East End and South London appear in terms of labor, charity, and tight domestic economies. Ford notes philanthropic institutions, missions, and model housing alongside lodging houses and small trades. He emphasizes that even marked differences are softened by manners and a shared preference for order. The city’s vastness allows enclaves to persist, but its public codes—reserve, punctuality, and respectability—help create a common urban temperament across boundaries of class and neighborhood.

The Thames provides a unifying thread. Ford treats the river as both memory and mechanism: barges, piers, and embankments testify to commerce, while bridges knit districts into a single organism. Transport extends this integration. The Underground, suburban railways, and omnibuses widen the city’s reach, binding outer estates to central offices and theaters. Suburban growth, garden villas, and commuter trains form new habits of early departures and evening returns. The result is a city whose center remains intense but whose margins expand steadily outward. Movement itself becomes a civic education, teaching patience, cooperation, and the understated discipline that Ford identifies as characteristically London.

Institutions and governance appear as quiet frameworks for civic life. Ford describes the London County Council, vestries, and boards attending to water, lighting, sanitation, and bridges. The police are depicted as firm yet unobtrusive, guardians of custom more than spectacle. Law courts, ministries, and ceremonial sites anchor the imperial capital’s authority without dominating daily experience. Churches, schools, and charitable bodies shape morals and opportunity; newspapers and clubs channel opinion. Immigration and cosmopolitan influences are acknowledged as elements absorbed into prevailing habits. The net effect is a city ordered by consensus and precedent, less by decree, sustaining a public mood of stability and practical compromise.

In closing, Ford gathers his observations into a portrait of an organism whose essence is continuity under pressure. London’s soul, as he defines it, lies in its diffused power, its capacity to absorb change, and its preference for steady effort over display. The city’s fogs, bridges, offices, theaters, and suburbs are parts of a single temperament formed by habit. While future traffic and expansion will alter surfaces, the underlying manners—reticence, reliability, and adaptability—are expected to endure. The book’s purpose is fulfilled in this cumulative impression: a modern metropolis understood through typical scenes that reveal a shared, persistent civic character.

Historical Context

Ford Madox Ford’s The Soul of London (1905) is set in the metropolis at the hinge of two eras: the last years of Queen Victoria and the early Edwardian reign of Edward VII. London in roughly 1890–1905 was the command center of a global empire, a city of over six million inhabitants whose daily rhythms were governed by docks, railways, newspapers, and the Stock Exchange. Spatially, Ford’s canvas stretches from the West End’s boulevards and clubs to the East End’s alleys and wharves. The river Thames functions as artery and stage, moving commodities and people while reflecting the city’s fog, smoke, and electric light.

The book’s time and place are the living city of everyday circulation: omnibuses and cabs on the Strand, clerks pouring into the City at Cornhill, laborers massing by Limehouse and Poplar, and shoppers threading Oxford Street. Ford writes as London undergoes rapid technological and administrative modernization, yet retains medieval street plans and stark social hierarchies. The Edwardian moment brings pageantry and a loosening of Victorian manners alongside unresolved social questions. His survey registers the crowds’ new tempo—the acceleration of transport, news, and advertising—while anchoring the narrative in specific neighborhoods whose character had been reshaped by rail termini, markets, and municipal works.

A crucial frame was the creation of the London County Council (LCC) in 1889 under the Local Government Act 1888, replacing the Metropolitan Board of Works. Dominated by Progressive reformers until 1907, the LCC unified metropolitan governance for 4.5 million people, coordinated bridges, roads, and sanitation, and launched ambitious housing and tramway programs. It oversaw projects such as the Blackwall Tunnel (opened 1897) and standardized building by-laws. In The Soul of London, Ford’s attention to the impersonality and scale of modern administration mirrors the LCC’s new bureaucratic reach: the city appears as a managed organism whose arteries and wards shape inhabitants’ movements and destinies.

The metropolitan transport revolution between 1863 and 1905 transformed how London was experienced. The Metropolitan Railway (1863) and District Railway (1868) were joined by deep-level electric tubes: the City & South London Railway (1890), Waterloo & City (1898), Central London Railway (1900), and Great Northern & City (1904). The LCC electrified tramways from 1901, expanding cross-river mobility even where the City barred tracks. Bridges and tunnels—Tower Bridge (1894) and Blackwall Tunnel (1897)—rechanneled flows, while the first motorbus services appeared in 1902; the Motor Car Act (1903) imposed number plates and a 20 mph limit. Ford’s prose, registering the city’s hum and hurry, directly reflects these new speeds, crowded platforms, and the democratization of distance that blurred neighborhood boundaries.

London’s docklands underpinned the global economy. The East and West India Docks, Royal Victoria (1855), Royal Albert (1880), and Tilbury Docks (1886) handled tea from Assam, grain from the American Midwest, wool from Australia, and jute from Bengal. By the early 1900s London was the world’s busiest port, with tidal basins, warehouses, and rail sidings sprawling from the Isle of Dogs to Tilbury. Casualized labor, hired daily at dock gates, kept costs low and insecurity high. Ford’s river scenes—barges, lighters, and bell-ringing steamers—encode this imperial logistics, rendering the Thames not as picturesque backdrop but as conveyor belt linking East End labor to distant plantations and mines.

Mass immigration reshaped the East End between 1881 and 1905, especially with Jewish refugees fleeing pogroms in the Russian Empire after 1881 and 1903. Tens of thousands settled in Whitechapel, Stepney, and Spitalfields, founding synagogues, Yiddish presses, tailoring shops, and mutual-aid societies. Public controversy culminated in the Aliens Act (1905), Britain’s first modern immigration law, introducing registration and powers of exclusion at ports like Tilbury. Ford’s observations of street markets and workshop life echo this demographic shift: he charts languages and customs mixing along Commercial Road, while registering how debates about “aliens,” overcrowding, and labor competition were inscribed in the very pavements and lodging houses he describes.

Scientific social investigation framed how Londoners conceived poverty. Charles Booth’s Life and Labour of the People in London (1886–1903) mapped every street into color-coded classes from “A” (vicious, semi-criminal) to “H” (wealthy), concluding that roughly 30 percent of Londoners lived in poverty at the end of the 1880s. Joseph Rowntree’s 1901 study in York found 27.8 percent in poverty, confirming structural, not moral, causes. Settlement houses such as Toynbee Hall (1884) embedded university graduates in Whitechapel to study and alleviate deprivation. Ford’s insistence on the city’s layered “souls”—the respectable poor, the casual laborers, clerks with precarious salaries—mirrors Booth’s empirical stratification, translating data into the sights and rhythms of streets, stairwells, and docks.

Labor conflict and organization surged in the late 1880s. The Bryant & May Matchgirls’ Strike (Bow, 1888), catalyzed by Annie Besant, protested toxic phosphorus and fines. The London Dock Strike (1889), led by Ben Tillett, Tom Mann, and John Burns, demanded the “dockers’ tanner” (6d per hour) and won after five weeks, aided by Cardinal Manning’s mediation. These successes birthed “New Unionism” among unskilled workers and fed into the Labour Representation Committee (1900) under Keir Hardie. Ford’s London is attentive to the mass—queues at gates, crowds in Trafalgar Square—and to the dignity and volatility of collective action, rendering the city as a theater of bargaining, procession, and public speech.

Women’s political mobilization reconfigured London’s streets. The National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (1897), led by Millicent Garrett Fawcett, pursued constitutional campaigning from offices near Westminster. The Women’s Social and Political Union (founded 1903 by Emmeline Pankhurst) soon brought militancy, attracting attention with confrontations at Parliament and high-visibility marches. By 1905 arrests and disruptive tactics signaled a new phase. Ford’s depictions of processional life, pavements, and police lines echo these contests over civic space: the book’s sensitivity to how crowds are seen and regulated resonates with women’s claims to visibility and voice in the imperial capital’s ceremonial core.

Housing reform sought to replace notorious slums. The Housing of the Working Classes Act (1890) empowered authorities like the LCC to clear and rebuild. The Boundary Estate (opened 1900) rose on the site of the Old Nichol, once among London’s worst rookeries; Peabody Trust blocks and Octavia Hill’s managed cottages provided alternatives across Southwark, Westminster, and Bethnal Green. Yet demolition often displaced the poorest to even cheaper rooms farther east. Ford’s survey tracks this churn: tidy red-brick model dwellings juxtaposed with ramshackle courts, rents inches beyond a clerk’s means, and the long commutes that tethered respectability to fragile weekly wages.

Policing and urban fear marked the city’s imagination. The Metropolitan Police, centralized since 1829, modernized rapidly under commissioners like Sir Charles Warren (1886–1888) amid unrest and mass demonstrations. The Whitechapel murders of 1888—never solved—etched images of gaslit alleys and sensational journalism onto London’s psyche. “Bloody Sunday” (13 November 1887) in Trafalgar Square revealed how policing, poverty, and politics collided. Ford’s nocturnal London, with watchful constables and uneasy crowds, carries these echoes: the sense that density can turn to menace, that anonymity shelters both aspiration and crime, and that order in the capital is always negotiated in public view.

Imperial pageantry filled central thoroughfares. Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee (1897) sent colonial contingents, battleship crews, and viceroys through the City and the Mall, while Edward VII’s Coronation (1902) rehearsed new ceremonial geographies linking Buckingham Palace, Admiralty Arch, and Whitehall. Relief of Mafeking celebrations in May 1900 produced delirious street scenes. Such spectacles stitched colonists to metropolis and asserted British power. Ford’s attention to flags, uniforms, and the choreography of crowds records how ceremony choreographed civic time: a city habituated to parades and reviews, in which public emotion could surge from solemn spectacle to carnival within hours.

The Second Boer War (1899–1902) tested imperial confidence. British forces fought in the Transvaal and Orange Free State, enduring sieges at Ladysmith, Kimberley, and Mafeking, before victory under Roberts and Kitchener. Approximately 22,000 British soldiers died; revelations by Emily Hobhouse (1901) about civilian concentration camps prompted the Fawcett Commission and inflamed debate. In London, recruitment meetings, casualty lists, and war news dominated Fleet Street and public houses; jingoism mingled with dissent from socialists and Nonconformists. Ford’s urban crowds carry this ambivalence—at once celebratory and anxious—revealing how imperial war saturated the city’s conversations, charities, and rituals of mourning.

Technological modernity rewired perception. Telegraphy linked London to the empire via the 1870s submarine cables; telephone exchanges spread in the 1890s under the National Telephone Company; pneumatic tubes whisked telegrams beneath streets. Mass-circulation newspapers like the Daily Mail (1896) and Daily Express (1900) pioneered sensational headlines, while electric light redefined shop windows and music halls. Advertising hoardings multiplied along thoroughfares such as Holborn Viaduct. Ford portrays London as an information engine: a place where headlines dictate talk on omnibuses, where illuminated signs and tickers flood the eye, and where the city’s “soul” is inseparable from the tempo of its messages.

Suburbanization redrew social geographies. Rail termini—Paddington, Euston, Waterloo, Liverpool Street—projected commuter lines into Middlesex, Essex, Surrey, and Kent. Ilford’s population, for example, rose from 7,467 (1881) to 41,117 (1901) and 78,188 (1911), emblematic of villa suburbs with gardens and season tickets. Tram extensions in places like Walthamstow and Croydon expanded affordable travel. This centrifugal pull relieved central densities while creating new class gradients and daily migrations. Ford’s contrasts between the City at noon and outer districts at dusk capture the pendulum of commuting, the Sunday quietude of red-brick avenues, and the psychic distance wrought by a mere half-hour train ride.

As social critique, the book exposes the contradictions of imperial prosperity: the simultaneity of glittering West End consumption and East End insecurity, of imperial parades and dockside hunger. Ford maps the city’s inequities without pamphleteering, using routes, queues, and thresholds to show structural barriers—rent, fares, seasonal work—that regulate aspiration. He dwells on clerks’ precarious respectability, the sweated tailor, the exhausted carman, and the invisibility of domestic labor, turning geography into an index of power. The city’s vast institutions—railways, police, newspapers—appear both enabling and coercive, disciplining bodies and desires in exchange for speed, spectacle, and wage.

Politically, the survey questions complacency about governance and progress. The LCC’s achievements sit beside displacement; public order shades into suppression when crowds demand bread or votes; immigration debates reveal anxieties about nationhood hardened into the Aliens Act (1905). Ford’s London registers the price of modernity: noise, anonymity, and the atomization of community alongside new freedoms of movement and leisure. By interlacing imperial logistics, war memory, and social investigation with the city’s daily choreography, the book indicts a system that naturalizes class divides and precarious labor, yet also imagines reforms—safer streets, fairer wages, humane housing—inscribed into the very map it reads.

Author Biography

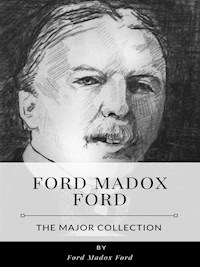

Ford Madox Ford (1873–1939) was an English novelist, editor, and critic whose career bridged late Victorian literature and high modernism. Remembered above all for The Good Soldier and the Parade’s End tetralogy, he also shaped the literary field as a pioneering magazine editor who championed new voices. His fiction is noted for psychological depth, shifting perspectives, and experiments with time that influenced later narrative practice. Trained in journalism and criticism as well as fiction, he articulated a coherent theory of “impressionism” in prose, arguing that novels should capture the felt texture of experience. Across genres, he combined cosmopolitan outlook, technical innovation, and a strong historical sense.

Raised in a culturally saturated environment, Ford absorbed the visual aesthetics of late nineteenth-century art and the cosmopolitan literary tastes of the period. He read widely in French and English traditions, admiring Flaubert’s discipline, Maupassant’s economy, and Henry James’s psychological nuance. Formal schooling prepared him for a life in letters, but his real education came through proximity to working artists and critics, early immersion in journalism, and the habit of close reading. These influences informed the narrative techniques he later defended in essays and prefaces, especially his belief that fiction should render perception as it is experienced rather than as a tidy chronology, an ideal he pursued throughout his major works.