Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Heliotrope Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

The Summer My Sister Was Cleopatra Moon is an emotionally charged, cautionary tale about alienation and the spiritual deformity that ensues when it feels like the whole world hates you. In the summer of '76, with no other Koreans in Glover, Virginia, fourteen-year-old Marcy Moon idolizes her irreverent big sister Cleo, who has her pick of lovers and uses her sexuality to prevail against racism. In Marcy's eyes, every guy would cut off his ponytail, burn his guitar and shoot old ladies if you told him to. Her dream, a dangerous one, is to be like Cleo. Central to the story is the girls' inability to bond with their mom, who left her heart behind in North Korea and finds it difficult to love her daughters the way a mother should. Most heartbreaking is the sisters' love for their dad, a complicated and worldly man who wants to be the best father and provider, but, in the end, cannot escape his demons.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 182

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Advance Praise forThe Summer My Sister Was Cleopatra Moon

“In her coming-of-age novel about two sisters, every page of which bears the imprint of her emotional and spiritual investment, Frances Park shows what a woman writer can achieve with such rich material at hand.”

—The Strait Times, Singapore

“… bold, powerful comedy… The parents in particular are sketched with an unflinching eye for pathos that can be fairly heartbreaking… Frances Park’s writing on adolescence is readable, unsentimental and… entrancing.”

—The London Times

“This is a delicate, humane, funny novel… that stands within the best tradition of imaginative writing.”

—The Taipei Times

“Park’s poignant novel… comes to us as a cautionary tale about the perils of the American dream.”

—The Korea Times

“The story captured a vivid image of sisterhood in all its complex glory and gore. I couldn’t put the book down.”

—The Korean Quarterly

“… written with gusto… and will likely find a place in summer beach bags.”

—Washington Post Book World

“A deftly funny, but in the end, heartbreaking exploration of a first-generation Korean family trying to make their way in a ‘70s suburban America that doesn’t always welcome them. As innocent Marcy, the “good girl” protagonist, rebels against the adviceof her parents and older sister Cleo — a hell-on-wheels beauty — and falls for the wrong boy, we can’t help but identify, as well as fear, for her. Told with a delicate, thoughtful, and true voice.”

—Steve Adams, Pushcart Prize-winning author of Remember This

“Fourteen-year-old Marcy Moon longs to be like her older sister, the girl with a cocky attitude and kaleidoscope eyes. The Summer My Sister Was Cleopatra Moon is a beautifully written tale of a fractured family, held together in Virginia by their Korean roots. Frances Park’s narrative is so direct and unassuming, you’ll feel like a friend is sitting with you, telling you a story you don’t want to end. You’re going to love this book. I did.”

—Maury Z. Levy, National-award-winning journalist, editor, and author

“Marcy and Cleo are Korean American teens, one generation removed from post-war Korea. To conquer racism, older sister Cleo—with her Cleopatra-painted eyes—uses beauty as her weapon, with innocent Marcy yearning to follow in her footsteps. Then there is the helplessness of a mother with her broken English and struggle to acclimate to American life, and a doting but tortured father whose profession takes him halfway around the globe from the ones he loves. The writing is brilliant as author Frances Park pulls you into this coming-of-age story from the very first page.”

—Rick Cooper, lyricist and author ofFor The Record

“Searing yet tender, this story is both unique and universal, specific to the turmoil and prejudice of late ‘70s America and timeless. It brims with the ways that families hurt and help, try and fail and fiercely love one another. The Moon sisters will step straight from their yellow convertible and into your heart.”

—Mary Quattlebaum, author of Grover G. Graham and Me and Brother, Sister, Me and You

“Family is both our anchor and the wind that pushes us apart in The Summer My Sister Was Cleopatra Moon, an emotionally raw novel that will live inside you long after you read the last sentence.”

—Bill Adler,author of Outwitting Squirrels and Boys and Their Toys

The Summer My Sister Was Cleopatra Moon

First published by Talk Miramax Books/Hyperion

SECOND U.S. EDITION

Copyright © 2000, 2023 Frances Park

This is a work of inspired fiction, with overlaps to actual experience. All scenes are created and imaginary.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by an information storage or retrieval system now known or hereafter invented—except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review to be printed in a magazine or newspaper—without permission in writing from the publisher.

Heliotrope Books, LLC

The opening chapter of this novel appeared as a short story in COOLEST AMERICAN STORIES 2022.

Some reviews that appear on the introductory pages are from the first edition.

ISBN 978-1-956474-32-9

ISBN 978-1-956474-33-6 eBook

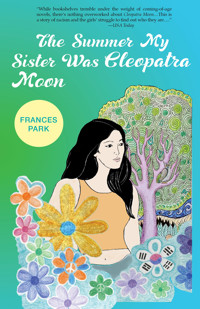

Cover art work © 2023 Naomi Rosenblatt and © 2023 Nico Sheers

Cover design by Naomi Rosenblatt with Frances Park

Typeset by Naomi Rosenblatt with AJ & J Design

To Mom and Dad. Always.

“Dance until you shatter yourself.”

—Rumi

Preface

In the ‘90s — long before K-Pop and K-Dramas entered the American psyche — I wrote what I thought was a brave little book. Brave because I feared my story about the fictional Moon family in 1976 white suburbia might not draw enough readers; after all, Koreans in America weren’t as visible then, and if any novels about such a family even existed, I’d never heard a peep.

Eventually, as announced in the New York Times, my book sold and was published under a similar title in 2000. Reviews, though spare, offered praise. Film rights were optioned. Yet in the end, my book fell off the radar.

Nearly a quarter century later, stories about the Asian American experience have certainly come to light. And during those years, playing in my mind like vintage footage, I was always hoping that somehow, someday, I could bring the Moon family back to life, sisters Marcy and Cleo cruising around in that yellow Mustang on their way to Taco Town.

All the stars fell into place last year when Heliotrope Publisher Naomi Rosenblatt, who had previously published my memoir That Lonely Spell, fell in love with a sparkly and streamlined version of the novel and offered to publish The Summer My Sister Was Cleopatra Moon. Second chances are rare, and I am incredibly grateful.

1

Cleo was back, her yellow convertible Mustang lined up with the buses. I remember running down the school steps so fast I beat the bell. When she saw me, she went wild with her signature honk —beep, beep, beeeep!— calling up something I can’t imagine today. My big sister at the wheel. My heart racing.

“Cleo, you’re home!”

She hugged me like a beloved rag doll and wouldn’t let go for a long time. I needed that hug; it almost got me crying. What stopped me was the shocking sight of her bosom spilling out of a red and white striped tube top. In those days I lived in Cleo’s hand-me-downs — her faded jeans and old T-shirts — but the thought of me in that tube top next year was going too far. I would never have deep cleavage or wear Wet ‘n’ Wild Hot Pink Lip Gloss so deservedly. And my hair was black straw, no matter how I cut it. It would never move like the ocean when I walked. Our mother often pointed out that Cleo inherited her beauty from our grandmother, but Cleo brushed this off like dirt. I don’t think she wanted to be linked in any way, shape, or form to some Korean peasant squatting in the fields. Could I blame her?

Cleo played with the tuner on the radio, her wrist jingling with silver bangles. “I can’t get over how cute you’re getting, li’l one,” she lied though her teeth. “I’m so jealous.” When she found her song, she lip-synched, and her faux diamond-studded sunglasses caught the sun in a dazzling display of how the whole world can miraculously turn. The Mustang’s top was down, and the sky was blue. Cleo shifted into gear.

“Hang on, school’s out for summer!”

And with one rebellious thrust we zoomed past Glover Intermediate and bus 14. I secretly flipped off the creeps on the bus, namely Mitch Mann, Dave Kelly and Frog Fitzgerald. Next year they’d get me, at another school, on another bus — probably spend their whole stupid summer thinking up a new name to call me — but now I was with Cleo. Idol of my life and the hereafter. In this world, in this Mustang, they were nothing to me.

I blinked and we were on the Beltway, weaving in between trucks. Our destination—Taco Town, two exits up. If Taco Town were a million miles away, we could keep on driving. Watch the sun set and the moon rise in our eyes. If the exit ramp curved on forever, we could go round and round and round, carnival-style. I could do it, live on the edge of a spectacular never-ending dream: Cleo and me, running for our lives. It would beat real life, as long as it would last. It would beat reading American Teen Magazine, if I never woke up. When we got to Taco Town, we pulled into the drive-thru.

The summer before Cleo had a boyfriend named Leonard who worked here on weekends. He was older than Cleo with a stringy blond ponytail, though his beard was reddish-brown. She dumped him, but she still hungered for Leonard’s love, day and night.

“He really loved me, Marcy. He would shoot old ladies if I told him to. Two Beef ‘n’ Bean Burritos and two large Tabs!” she hollered into the mike.

“He had a neat van,” I said.

A cruel smirk came over her face, one I easily recognized. She was reliving the night she broke Leonard’s heart, the night she cruised through the drive-thru with her hands all over Chuck Boucher. They’d been to a pool party and drank tequila under the deck. How many times had I heard the story?

We took our food and parked in our old spot, which faced a run-down route of strip malls and whizzing traffic. It was bleak, for Washington, DC suburbia. Potholes, USA. Namely, Glover, Virginia. And there we savagely ate that afternoon in 1976. Nothing ever tasted so good, wolfing down a pillow of grease, the traffic music to my ears. In a blinding sun my eyes squinted into mere slits as Cleo lit up a menthol cigarette like a movie star.

“Are you home for the summer?” I asked. “The whole summer?”

My loneliness always hit her right in the gut. She crumpled up the bag with conviction. “I’m not going anywhere, li’l one. You want to go to the mall, we go to the mall. You want to go to the pool, we go to the pool. Get the picture? It’s you and me from now on. The rest of the world can go up in flames.”

“You mean until September,” I lamented.

“No, I mean from now on. I’m thinking about dropping out of Jamestown, aka Dumbo U.”

My heart stopped like a clock. Cleo and me, Cleo and me, Cleo and me. Just like the old days!

“But Mom and Dad will kill you!”

“I don’t care! I can’t face all those Petunias in the dorm again! Pigs!”

I knew all about them. I had read each and every one of her letters from college so many times I knew them by heart. There was Libby, who went around telling everyone Cleo was a syphilitic slut. And Patty, who claimed she saw her making out with a girl in some townie bar. And Maureen, who spread a rumor on frat row that Cleo shaved her breasts. An article in American Teen — ‘Make Friends with Jealous Foes’ — said to take the calm, rational approach. Take a deep breath. Talk it out. But Cleo could drive girls to murder. Their angry eyes were on her everywhere we went. In malls, at the movies. Everywhere!

Three guys walked by us, going nuts over Cleo like hungry baboons.

Va va voom!

Give papa a kiss!

Sweet mama!

Cleo flashed them a smile that could make her famous. To me she was famous, and I was content to live in her glamorous fog.

“Cleo, every guy on the face of the earth wants you,” I moaned, knowing that was what she wanted to hear. The world moaning her name.

She basked in her glory with a marvelous sigh and a flip of her sunglasses. That’s when I saw what I’d be staring at all summer. Her eyes! They were painted black with dramatic wings at the tips.

“Cleo?”

“Call me Cleopatra,” she winked.

We went by Cleo and Marcy, but those were not our birth names.

We had adopted them at some point and thrown the others away as if to hide the evidence, even from ourselves. The occasional sight of Misook on my report card struck a nerve and for an ugly moment I’d be reminded of who I was. The only Korean girl on this side of the planet. Besides Cleo, of course. But she didn’t count. Who on earth would make fun of her? She walked with her head up high, crowned by her own confidence.

And now she had those eyes! They came out of a tiny Max Factor bottle I had seen advertised in American Teen. It was labeled Waterproof Eyeliner, and they weren’t kidding. Cleo slept and showered and swam in those eyes — they never came off. After a while I got used to them, although my parents didn’t.

“You are not Cleopatra under this roof!” my father argued. He was a Harvard man, born to debate. But not with his daughters. “You are Kisook Moon. Do you understand? Do you hear me?”

“Don’t call me that,” she said, covering her ears. “I am Cleopatra Moon, I am Cleopatra Moon, I am Cleopatra Moon!”

My father had endured many hardships in his life, but none could affect him like the disobedient voice of his elder daughter, a voice seldom heard because he usually looked the other way. On the rare occasions they fought, he would lock himself in his room and review a lifetime of suffering — poverty, war, his parents, whom I hated horribly. Cleo always went to him, knowing his sorrow wasn’t to be taken lightly. She’d knock on his door, and it wouldn’t be long before I’d hear them engaged in one of their long, philosophical talks, which my father desperately needed. Still, Cleo always got her way. The eyes stayed.

With my mother, the clattering of pots and pans said it all. She and Cleo had a history of bickering — over glitter nail polish, skimpy outfits, barefoot boyfriends — but these days she wasn’t saying much. Her own history of fleeing her North Korean homeland as a child left her feeling helpless as an adult. Deciding which bunch of scallions to pick at the A&P could put her in a panic. Once picked, she’d still fret, sometimes turning the cart back around.

My parents had come to America in 1954 so that my father could go to graduate school and study Public Administration. It was to be a temporary stay, but my father’s ambitions were thwarted by the overthrow of South Korean President Syngman Rhee. The political climate was too dangerous for a former aide who had his eye on the presidency himself one day. So he began a life here as a transportation economist at The World Bank in the nation’s capital while starting a family in the Virginia suburbs. It wasn’t the life of his dreams, but it was noble work and he adjusted very well with his impeccable English. Most Americans assumed he came here by way of Oxford. My mother didn’t ask any questions and although she had many housewife acquaintances, never mastered the language. Chipmunk was munkchip, fold the clothes was hold the clothes, and when the girl next door asked to borrow a pitcher, she came back to the door holding a baseball bat. She was adorable, through no effort of her own. All the neighbors loved Mama Moon.

A week into that summer break, Cleo got a job as a cashier at The Rec Room. The sign for help had read CHICK NEEDED — TALK WITH TED THE HEAD. The Rec Room sold albums, eight track tapes, guitar picks, incense, and what they advertised as big bad bongs. Meanwhile, I spent my days going to summer school and tutoring a dyslexic set of twin brothers named Tim and Tom.

At night Cleo and I hung out at the pool.

“Not a word to them about me not going back to school,” she warned me, turning down her transistor radio. She wore a wild Hawaiian print bikini that could fit into a thimble. “Promise me, not a peep. I’ll have to break it to them gently. What’s a degree from a state college like Dumbo U going to do for me anyway?” She looked at me like I’d have an answer. I did, from the pages of American Teen.

“You need a college degree,” I recited, even though I’d die a million deaths if she left. “You need it to get a good job, Cleo,” I said.

“Cleopatra.” She batted her painted eyes.

“Cleopatra,” I said.

“I’m not cut out for college. I’m not a genius like you. Einstein with pierced ears.”

“No, I’m not.”

“Yes, you are! You’ll go to some Ivy League school and become something greater than the whole bourgeois universe put together.”

“No,” I stammered.

“Right now, right this second, under this ho-hum hick sky, you may be li’l Marcy Moon, but someday I’ll look up and say, ‘There’s my superstar sister, beaming over us mere mortals.’”

“No, I’m nobody, I’m — “

She frowned. “Who?”

I almost did the unthinkable — reveal my nickname at school. Miss Moonface. Down the hallway, on the bus, in the cafeteria. Miss Moonface, Miss Moonface, Miss Moonface.

“I’m nobody special,” I said.

“Bull! You’ve got God-given smarts! Why do you think you’re already taking Algebra II and teaching Mit and Mot that Z ain’t A? Not everybody can write a paper in Frenchon Waiting for Godot while watching Welcome Back, Kotter and reading teenybopper mags.”

“But I study a lot, Cleo.”

“Cleopatra,” she sang impatiently.

“Cleopatra,” I said.

“Well, I study, too, and I flunked Chem Lab. Blew away my dreams of being a mad scientist!”

Cleo made fun of my American Teen magazines — two years of back issues on my bed — but I learned about love from ‘Dear Romeo & Juliet’, fashion from ‘Suit Yourself’, and life from ‘Socrates Speaks’. Ever since my only friend and songwriting partner, Meg Campbell, moved to Texas last March, American Teen had been my sole source of companionship. Until Cleo came back, of course, and by then I was hooked.

Meg and I were determined to write what we coined The Song of The Century. Someday. But now that she was gone, and The M&Ms were broken up, all I had were our B songs to remember her by.

Someday, one day

I shall leave this place forever

and find my hopes and dreams.

Someday, one day.

I want to laugh.

I want to cry.

I want to live.

I want to die.

So that I can be free.

So that I can be me.

Word of Cleo in her bikini got out, and in no time she had so many boyfriends at the pool I couldn’t count them. They would go out with her to her Mustang and make out like mad and do who knows what — how could I tell from the snack bar? All the while she was on the lookout for Leonard, who used to do backflip dives here high as a kite.

“When’s he going to show up?” she wondered, adjusting her bikini bra. “Surely he’s heard I’m back.”

A track of small red bites on her neck silenced me. I think I will always equate the smell of chlorine on a warm summer night with the first time I smelled sex.

She flopped around in her pool chair like a lovesick fish. “I miss him, Marcy. No one comes close to loving me as much as Leonard.”

“He’d cut off his ponytail, burn his guitar and shoot old ladies if you told him to,” I said.

“He’d die for me, li’l one. Up and die. But I guess I really hurt him, didn’t I? The thought of me with Chuck Boucher did a number on him, didn’t it?”

“It broke him in two,” I assured her.

Porcelain dolls and delicate flowers — symbols of Eastern grace and beauty. But Cleo was no fragile object. She was statuesque, built to command the sun and the moon and the atmosphere on earth. Her hair was mink, and she wore it like a coat. People were stunned when they saw her, as though she had just walked out of a painting and into Dart Drug. Males were often moved to utter something, anything, even some Neanderthal grunt, as if, otherwise, they’d lose their chance forever. I remember an older guy with beer breath approaching us at the salad bar at Ponderosa Steak House and saying to her, Miss, I’m a happily married man with four kids, but I just wanted you to know you’re a breathtaking woman.

I never dreamed of that power myself. It was not within my realm of dreaming. If God gave me smarts, He gave her looks for two. Cleo was always saying my turn was next, but I knew it would never happen, not in this lifetime. There was only one Cleo.

A special summer edition of American Teen hit the newsstand. It was a double issue, jam-packed with gossip, fashion, and celebrity interviews. The first annual ‘Dream On’ essay contest was also announced. The topic? Whatever you dream on. The grand prize winner would have her essay and photograph published in next year’s Valentine’s Day issue. I pictured my face in there, surrounded by a lacy heart. I read the announcement over and over. Calling all American Teens!Send your most heartfelt essay with a recent photo.

To write the winning essay — could I do it? I wanted so badly to be part of American Teen, even the notion of it hurt worse than any growing pain. But did I have a dream? What did I dream on?

From a poster taped up in the window of The Rec Room, Cleo discovered that Leonard was now playing guitar in a band called EZ Times in a Georgetown bar. She got in the habit of dropping me off at home and cruising down there with some guy she just met at the pool. Her plan? To drive Leonard mad with jealousy. I would wait up for her, dreaming on.

“Marcy?”