Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

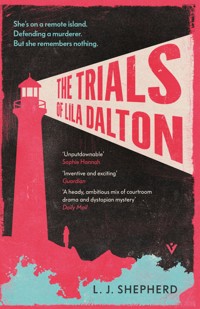

SHE'S ON A REMOTE ISLAND. DEFENDING A MURDERER. BUT SHE REMEMBERS NOTHING. 'Unputdownable' Sophia Hannah 'Mind-blowing, audaciously inventive' Chris Whitaker 'Totally recommend. Stuart Turton meets Agatha Christie' Sarah Moorhead 'A heady, ambitious mix of courtroom drama and dystopian mystery' Daily Mail Lila Dalton finds herself in the middle of a courtroom as the barrister for a man accused of a terrible crime. She has no memories of her life before this moment. Outside, on the strange island where she is staying, things are even more unnerving: hostile locals, tapped calls, threats slipped under her hotel door. Hints from mysterious sources suggest that someone from her forgotten past is in danger - but are the threats genuine? As the trial progresses, Lila must decide who and what she can trust, and whether that includes herself... __________ 'Feverishly compulsive' Sabine Durrant 'Inventive and exciting' Guardian 'Remarkable' The Times 'Terror lurks at every corner' FT 'Brilliantly written' Natasha Pulley 'Achingly atmospheric' Kia Abdullah 'Captivating' Adam Hamdy

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 519

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Contents

1

I look up to find twelve strangers staring back at me: six in the front row, six in the back. They seem expectant, like an audience waiting for a comedian to deliver the punchline.

I realize I’m the one they’re waiting for. Now would be a good time to tell a joke, just to ease the tension, or fill the silence at the very least, but I can’t think of anything to say. My mind has gone blank.

I don’t know where I am, or how I got here. I’m not even sure where ‘here’ is.

It’s an old-fashioned place. The twelve strangers are sitting in a wooden box—like pews in a church, except the back row is higher than the front, so more like seats in a theatre. Sort of. Everything from the skirting board to eye level is oak-panelled.

‘Miss Dalton?’

I look around for whoever said that and, at the front of the room, staring down at me from an elevated bench, is a man robed in scarlet and black. A judge. His eyebrows rise to meet his wig. I quickly decide that it’s a good job I didn’t deliver any funny lines. It doesn’t look like he’d appreciate them.

The presence of a judge tells me this must be a courtroom. That’s why everything looks so strange, why the walls are made of wood. Wait, am I on trial? What have I been accused of?

‘Miss Dalton?’ says the judge again.

I guess that’s me. Dalton… Dalton… The name means nothing to me.

‘I think the jury were hoping you might tell them which witnesses you’ll be calling for the defence.’

I repeat the phrase several times, but quietly, so that only I can hear. With each repetition, my head pounds and brings with it a wave of tinnitus. Witnesses… jury… defence. 8

It doesn’t matter how many times the words slosh around my pitching ship of a brain, I can’t think of anything to say. I feel sick with dread. Everyone is expecting me to know the answer, but I couldn’t even tell them what day it is. There’s been some sort of mistake. A horrible mistake.

Needing to feel my skin, just to check that there’s some fleshy casing for my broken mind, I raise a hand to my temple, and my fingers brush horsehair curls. I’m also wearing a wig. At least that explains why everyone is looking at me.

I cast around for more clues, even though the list of potential explanations is dwindling by the second. And those seconds are as long as minutes. Each one drags out into eternity while everyone waits for me to speak and I stay silent, though my mind is full of noise.

I turn to see what’s behind me. No longer looking for clues, I’m looking for an exit. In the middle of the courtroom sits a man encased in a glass box. Next to him is a uniformed officer with a pair of handcuffs chained to his belt.

Witnesses for the defence. This must be the defendant. I feel a rush of adrenaline that curdles with the realization that I’m supposed to be defending him.

I cast my mind back. How did I get to court? Did I get the train? I don’t even know what the case is about. Everything that came before is just… Nothing came before. This sends a fresh jolt of panic through me.

‘My Lord, may I trespass on the court’s time for a few more moments and request a short break?’

I have no idea where I learnt to speak like that.

His Lordship’s nostrils flare and he turns to face the twelve strangers. ‘Right. Members of the jury, I do apologize, but I’m afraid I must ask you to return to your room. I’m sorry about all this back and forth. As soon as we get into the trial proper, there’ll be no more games of musical chairs.’

There’s a titter that masks a grumble of impatience. As I sit down, my heart rams into my ribcage.9

The judge watches the jury leave one by one. When the door closes, his eyes whip to me. I stand up—not entirely sure why—but I suspect it’s the right thing to do.

‘Ten minutes.’ He gets up to leave.

‘Court, please rise,’ comes a voice from somewhere at the back.

Everyone does as they’re told.

I’ve got to get out of here, find someone who’ll help me. It looks like I’m a barrister, someone who has responsibilities and knowledge and—God help me—legal qualifications. That person, whoever she is, feels as much of a stranger to me as the judge or jury. Who knows what I’m supposed to be doing today, where I’m supposed to be? A word swims out at me from the depths of my non-existent memory. Clerks.

I find that I’m in the very pit of the court, sandwiched between rows of oak pews. The jury box, the judge’s bench and the public gallery all rise around me like an amphitheatre. I go to leave when—

‘Miss Dalton?’

It takes me a moment to remember that’s my name. I turn to see a man wearing a black robe so tattered and worn he looks like a wraith. His wig is the colour of earwax.

‘You’re making the right decision,’ he says. ‘Don’t call your client. It’ll only let his form in.’

The only thing worse than not knowing how to respond is knowing exactly what he’s talking about. He means that calling the defendant to give evidence will cause his previous convictions to go before the jury. How can I possibly know that? I don’t even know my name, my birthday, anything. I can’t picture my face.

‘Take as much time as you need,’ he says, his voice mellifluous. Instinct warns me not to trust him.

I’ve got to get out of here.

He continues muttering behind me, as though my turned back has rendered me deaf. He says something about why I’ve asked for a break. From the tone of his voice, I recognize that he’s telling a joke. Well, good for him. I can’t catch all of it because I’m heading away now, and don’t want him to know I’m eavesdropping.10

‘… her hemline will get higher with every day of this trial… His Lordship will be… pleased.’

I look down at my skirt. It’s straight and black and hits my calf just below my knee. What does he mean, ‘His Lordship will be pleased’? My cheeks flush. What sort of person is renowned for the length of their skirt? Perhaps I use my body, my ‘feminine wiles’, to get my own way in the courtroom. But that doesn’t seem like me. I know that’s not me.

I almost laugh; how should I know what I’m like? I’m the last person to be an authority on that subject.

But the shame brought on by his comment lingers, a weight that hangs around my neck. I don’t need to remember my past to know I’ve been spoken to like that or looked down on every day of my life.

I get away from the row of benches as fast as I can, glancing up at the poor sap in the dock. It looks like I’m his only hope. God help him.

There’s barely anyone in the public gallery. A couple of hacks sit in the press benches. I head for a pair of double doors at the back of the court with dusky-pink curtains shielding the windows.

After climbing a flight of stairs, I find myself staring at a long, low-ceilinged corridor. There are rooms all along the right-hand side like bunkers, and on the left is a windowless wall of glossy brown bricks.

‘Are you OK?’

I nearly jump out of this stranger’s skin. There’s a man standing next to me. Where the hell did he come from?

‘I’m Malcolm,’ he says.

Malcolm is a middle-aged man wearing the black robes and government-issue lanyard of an usher. The only hint of individuality is found in his glasses, which are round and golden. Something about his calm demeanour comforts me.

‘I need to speak to my clerks.’ How I know this is a mystery to me. But that clerks look after barristers is a piece of knowledge I’ve retained, so I clutch at it.

Malcolm smiles politely, ignoring my abruptness. ‘Follow me.’11

Rather than going down the long, straight corridor, we turn right and go up another flight of stairs and through another pair of double doors that open out into a hall the size of a small church.

My heels clatter on the black-and-white stone floor. It’s like a chessboard except, rather than squares, hidden beneath tables and chairs are triangles, diamonds and circles. Above me, there are three plaster ceiling roses held up by Doric columns.

Just as I’ve finished taking in the spectacle of the main hall, the clacking of my heels is muffled by red carpet. We’re navigating a maze of rooms and windowless corridors. Or Malcolm is.

Eventually we end up at a door that says ‘Listing’ on a brass plaque below a wired glass window.

Malcolm knocks before poking his head around the frame. ‘Miss Dalton wants to ring her chambers.’

He waves me inside where a woman is already dialling the numbers into a desktop rotary. She holds out the handset and I take it.

I don’t have enough time to wonder who will answer because after the first ring—

‘Two, Lawn Buildings, Tony speaking.’ Tony has a distinctive South Walean lilt.

‘Hi, Tony.’

‘Lila! How’s you?’

Lila… Lila… Still nothing. I feel the two Ls on my tongue but there’s… nothing. ‘What case am I doing today?’

There’s a wooden desk calendar next to the phone so I check the date. I realize that I don’t even know what year I’m in. 18 November 1996 it says in red letters.

‘Very good.’ Tony laughs nervously. ‘It’s ten-forty. Shouldn’t you be in court?’

‘Seriously, what case am I doing today?’

‘You are joking? This isn’t the time for—this is the biggest case of your career. You’re doing Eades.’

Eades?

‘Eades,’ I repeat back to him.12

‘The mass-murderer? Bombed the Home Office building?’

Shit. I’m doing a murder? A mass murder?

‘But…’

‘We had this conversation on Friday… Do you know how many juniors dream of their QCs being in a car crash the week before a trial?’

‘Jesus.’

‘All of that hard graft and there you are, doing it all on your own.’ Tony sounds like a proud father. It makes it harder to disappoint him.

‘But… I can’t.’

‘You can. Don’t doubt yourself now. Pat wouldn’t have chosen you as junior if you weren’t up to it.’

‘When are they coming back? My silk?’

‘Seriously, Lila. What’s wrong with you? Are you having another one of your…?’

Is this something I’ve done before? Am I unbalanced? Does Tony keep tabs on me, making sure I don’t take on too much work in case I burn out?

‘There was a car accident on Friday. Pat’s still in a coma. You know all this.’

‘Oh my god. I’m so sorry… I’ll go now, Tony.’

‘Go get ’em!’

I hang up, thanking the woman who dialled the number, and leave to find the main hall. Thinking over the conversation, I realize three things. First, as with ‘clerks’, I know what the words ‘silk’ and ‘QC’ mean. QCs—Queen’s Counsel—are senior barristers who wear silk gowns and take on only the most difficult cases. Second, I realize that Pat is my QC. Third, I realize he’s not here, so I have to do the case in his stead.

Just reciting these facts makes me feel calmer. But what I still can’t reconcile is my detailed knowledge of the legal world on the one hand and my total lack of knowledge of my own life on the other.

This must be what’s happened: I was so stressed about doing the case without a silk that I spent the weekend working into the small hours. Maybe I mixed caffeine and alcohol. Do I take drugs? Maybe I 13took drugs. This must be just sleep-deprivation or something. That’s why I can’t remember how I got to court. It’ll come back. I just need to take a few deep breaths, clear my head.

I’m not losing my mind. That’s one thing I know for sure.

I mean, looking at this logically, there’s nothing wrong with my cognitive functioning. Well, if you discount the fact I don’t know who or where I am, or what the last… however many years of my life have involved. Yes, ignoring that, I’m eloquent and methodical and seem to know stuff about the law. It sounds pretty temporary. It could just be stress, which would make sense given this is the biggest case of my career. I can’t give up just yet. What if in a couple of weeks I’m fine and I’ve just thrown away the opportunity of a lifetime? What will the future hold for me then—sitting out my days representing petty shoplifters until retirement?

If I tell people what’s happening, they’ll think I’ve lost the plot, they’ll want to shove me in an institution, and that seems a bit drastic given… Given I’m basically fine. See, perfect example. Just then, when I thought about being sectioned, an image came to me. Not a memory as such, not something I’ve actually experienced, but word association. A sterile corridor, long and white. It looms larger in my mind’s eye.

This thought jolts me back to where I am, where I’m supposed to be going. I’ve been walking along the same corridor for what feels like an age. I turn in the direction of what I’m sure is the main hall only to find that I’m back outside the listing office again.

‘Lost?’ It’s Malcolm. Christ, that man knows how to appear out of thin air.

‘I want to go to the robing room.’

2

I’m not sure where my urge to find the robing room came from. It was an emotional pull: find sanctuary.

Except the robing room I find is nothing like that. It’s all stale cigarette smoke and male body odour. The smell of smoke stirs something in me, a tug at the curtain in the far reaches of my mind. I think it’s a memory fighting to get out. I stop and try to reach for it, but it fades away, leaving me frustrated. Still, the fact that a memory tried to knock at the door gives me hope.

I look around to get my bearings. Everything in this room is either cherry red or cherry wood. The carpet, the wing-backed armchairs, the leather top of the vast oval table that dominates the middle of the room and the velvet lining of the dozen or so chairs that surround it.

Hanging from the domed ceiling is a dusty, cobwebbed chandelier with frosted orbs casting a yellowy glow.

I head for a wall lined by wooden cubbyholes. Wig tins and bible-sized books poke out from the odd open door.

One of the wooden boxes houses a mirror. Tabs hang limply from the compartment below.

When I look at my reflection, a stranger’s eyes stare back at me. They belong to a woman who looks to be in her thirties. I lift a hand to my face and am surprised when the hand in the mirror follows suit.

I remove the wig and run my fingers through my black hair and wince when my nails snag the knots. In this moment, I’m struck by how real I am, how corporeal. This is my body. I touch my stomach, all too aware of its softness, and find it odd to think that there is a whole machine of internal organs inside, working to keep me alive.

I look back at the woman in the mirror; it’s still too strange to think of that person as me. Dark brown eyes stare back at me, framed by thick, well-groomed eyebrows.15

That feeling I had earlier—tinnitus—it’s coming back, but it’s stronger now. I bare my teeth against the pain of it.

Constricting my neck is a collarette—a sort of bib with tabs jutting out of the front. I rip it off so I can breathe, and the Velcro snags the hair at the nape of my neck. I wrestle out of the gown, throwing it at one of the chairs. There are too many trappings. I just need to be rid of them all.

A childish thought takes hold: what if I can stay in here and never leave? Hole up among the coat pegs and make a den? The idea is so tempting, I’ve almost made my way over to the rows of pegs when something catches my eye—

A purple trench coat stands out from the tan-coloured macs and charcoal duffel coats.

Was it there before?

I look around and realize that I am not alone. In my panic, I failed to realize that, sitting with her feet on the table, is the only other person in the room. Her wig has been discarded, but her tabs are still in situ. She’s not wearing a collarette. Instead, she wears the tunic shirt and tabs that male barristers wear.

‘Good morning,’ I say, politeness filling in the large hole in my mind where intelligent thoughts should be.

‘Are you feeling all right? You seemed a bit rattled.’ She gestures towards my discarded wig and gown.

I look back at them, embarrassed. ‘I’m just feeling a bit… nervous.’ I join her at the oval table.

She surveys me, waggling her crossed feet which are shod, not in heels, but in patent brogues.

She catches me looking at them. ‘I never wear heels. Torture devices.’

‘No—I wasn’t—I’m jealous, actually.’ I rub the back of my ankle. Already my heels have made red dents in the skin.

We sit in silence. She looks at me like I’m an interesting exhibit while I search for a conversation starter.

‘So, my opponent is a bit of an arsehole,’ I say.16

She laughs. The sound is rich and gravelly, earned by Scotch, cigarettes and age. God, how I long to sound like that. ‘They haven’t tried to old-soldier you, have they? Don’t fucking let them.’

‘Well, aside from a sexist remark about my skirt…’

‘How original. You know, I think misogynists would be a lot easier to stomach if they showed a bit of imagination.’

I laugh. It feels good, almost human. ‘Then he told me I shouldn’t call the defendant to give evidence because it’ll let his previous in.’

She frowns while thinking over my predicament. Something on her arm is clearly irritating her as she reaches into her gown to scratch at the inside of her wrist. I see a flicker of faded ink before her gown falls back over her wrist.

She says, ‘Clients do have a habit of convicting themselves the moment they get in the box… But it’s poor form to rely on pre cons. I always think of it as cheating.’

‘Maybe he won’t want to give evidence. He doesn’t look very chatty.’

‘My fucker won’t shut up. Can’t wait to be rid of the old perv.’

‘What’s he accused of?’

‘Just being a perv. Serial perv. It’s all I do these days.’

The way she talks; the battle-weariness, the warmth, the humour. The way she peppers every sentence with fuck and perv. It’s such a welcome oasis in this strange world of wigs and gowns and glass boxes.

‘What did he do?’

‘Woman walks into a bar for a drink with her colleague. Next thing she remembers is waking up in his bed with a sticky substance between her legs. Repeat ad infinitum.’

Something about her story stirs something in me. I can picture the bar so clearly. The moody lighting—tinted blue. The sticky floor, the too-high stools. Even the smell of alcohol. I can picture it all. How? How do I have a frame of reference for that, what, with my puddle of memories gathered over the course of ten minutes?

‘Are you OK, dear? Thousand-yard stare there.’

‘Oh, yes. Sorry. I’ve just had a bit of déjà vu.’17

She smiles warmly. The kindliness of her face stands in stark contrast to her severely cropped grey hair and square, thick-rimmed glasses.

‘And what terrible crime brought you to this underworld of never-ending torment?’ she asks.

‘I’m a mass-murderer. My silk’s been in a car accident. I’m all on my own.’

‘There you are; you’ve probably just got a bit of imposter syndrome, doing a murder all on your own.’

‘Yes, that’s it!’ I say, so happy to finally have a name for it. Imposter syndrome is exactly what I’m experiencing.

‘Let me show you a trick I use whenever I feel a bit disorientated.’ She swings her feet off the table to stand up before walking over to the rows of wooden boxes. ‘Surname?’

A beat while I search for the information. What was it the judge called me?… Miss—

‘Er, Dalton.’

Her features betray a glimpse of recognition for a millisecond before she remembers herself. She searches the boxes, each one bearing a brass card holder, and finds one with ‘Dalton’ written in blue calligraphy. She opens the drawer and pulls out a copy of Archbold, the book barristers use as a reference text.

As she’s flicking through the pages, she says, ‘You know, déjà vu is completely natural.’

‘How so?’

‘Time is an illusion created by human memories. Everything that has ever been and ever will be is happening right now, in this moment.’

My mouth is open. This was not where I was expecting the conversation to go.

‘It’s true; look it up.’

‘I wouldn’t know where to begin,’ I say.

‘I don’t know—a book?’ She frowns as she flicks through the pages of Archbold. ‘Not this one, obviously. Dry as a bone this unwieldy thing. You’d want one on quantum mechanics or something.’18

I think over what she said. Time is an illusion created by human memories. ‘And… what if you have no memories?’

She smirks. ‘You’ll have to ask someone much cleverer than I. Ah!’

Having stopped looking through the pages, she lays the book open on the red leather inlay of the oval table.

‘Draw a mark here,’ she says. ‘If you have been here before, you’ll know because there’ll be a mark in the book. It’s my little trick for dealing with the totally normal and natural phenomenon we call déjà vu.’

I hesitate before getting up, feeling a little silly. Her smile is too encouraging to rebuke the offer of help, so I walk over, take the pen she holds out for me and make a little fountain-pen scratch in the top right-hand corner of the page, not really believing this will work.

She pulls the red ribbon from the binding and uses it to mark the page before handing it to me.

‘And imposter syndrome?’ I ask.

‘No cure, I’m afraid. Get stuck into the case and you’ll be too distracted to worry about whether you’re up to it.’

The purple coat catches my eye as I cast around for a way to say, ‘thank you’. Instead, I say, ‘I love your coat.’

She turns to look at it and smiles fondly. Scratching again at the patch of skin on the underside of her wrist, she says, ‘Anyway, best be off. My client’s probably in the cells now, dying to tell me how she came onto him… Revolting.’ She shivers before ramming her wig unceremoniously onto her head. She goes to leave before turning back to say, ‘Oh, and if the prosecution are trying to rely on some tatty old pre cons from when your client stole chalk at school, they’re clutching at straws, my dear. Don’t let them get away with it!’

And with that, she’s gone.

I stand for a while, mulling over what she said.

‘Miss Dalton, the court is waiting for you.’

· · ·

19‘No.’

I’m in amongst the coat pegs. The musty whiff of the rain-flecked trenches I’m wedged between confirms it.

‘His Lordship is waiting.’

‘It’s not that I don’t want to. It’s just that I really can’t.’ I stare up at Malcolm, my eyes wide and pleading, trying to communicate that this isn’t a joke and I really need help, just not of the medical variety. ‘Please.’

‘He’ll put you in contempt of court. He put a barrister in the cells last week when his conference overran by five minutes.’

‘But…’

‘You’ve got ten seconds, or you’ll be late.’ He starts counting.

I close my eyes and picture a set of scales. Placing weights on the one side, the side that represents getting the hell out of here, I consider that I don’t know who I am or what I’m doing. There’s no way I should be defending an alleged mass-murderer. But if I run away now that wouldn’t give me much of a head start, even if I managed to get past security. I take some weights off the scale before considering the alternative in which I play along and wait for the opportune moment. The scales drop to one side, and I resolve to at least get through the morning. Once it’s the lunch hour, I’ll make a break for it.

‘OK,’ I say, following him.

Before leaving, I stand in the doorway and take one last look at the robing room over my shoulder.

The purple coat is no longer there.

Though I’ve only just met Malcolm, what I like about him is that he lets me think in peace. Doesn’t try and strike up small talk. And boy, do I have some stuff to think about.

I decide to consider the evidence, put my critical thinking skills to the test. All of the empirical evidence suggests that I am indeed a qualified barrister. I seem to have some grasp of the law, and I’m certainly wearing the right outfit.20

However, the evidence of my eyes and ears doesn’t seem trustworthy, not when I can’t remember anything. That’s another puzzle: how do I know anything, speak English, let alone understand legal principles? If I have no memories, shouldn’t I be like a baby? When a child touches a flame, it burns their skin and they learn not to do it again. Knowledge and memories are intertwined yet mine seem to have become… untangled.

Perhaps I should test myself, feel out the edges of my knowledge. What would a doctor ask if they were trying to ascertain whether someone was sane? They’d probably ask who the prime minister is. The desktop calendar in the listing office said that today is the 18th of November 1996. Assuming that’s correct, the prime minister must be… I stretch for the piece of information, and my brain creaks with the effort of it; an old, infirm person trying to reach their toes.

John Major.

I did it! A rush of happiness and I beam.

‘Are you all right?’ asks Malcolm.

‘Yes, thank you.’

‘I saw a smile for a second there.’

‘I just had a thought about the case, a new line of attack, you know? It’s nice when you get a bolt of inspiration.’

Malcolm nods and retreats into silence as we walk along the red-carpeted corridor which connects the robing room and the main hall.

I turn back to my predicament. If my general knowledge is fairly intact but my personal knowledge isn’t, then it seems as though I’ll recover from whatever is the matter with me. If this memory loss is temporary, and I have to hope that it is, there’s a Lila Dalton in here whose career is resting on this case, on me getting it right. Maybe Lila’s memories will come back, and so will Lila, with all of her quirks and foibles. And her experience, for Christ’s sake. That’s what I need right now.

The alternative is that it’s permanent and I will never regain my memories. Either way, I need to get out of here. It would be wrong, unethical even, to represent someone when I’m psychologically 21compromised. But then if my memories do come back and I’ve withdrawn partway through a trial… cross that bridge when I come to it, I suppose. I notice the signs overhead with arrows pointing to different courtrooms, to the washrooms, to the cells, and take note of where the exit is for when the opportunity to escape presents itself.

We’re in the main hall again. The clattering of my heels echoes in the empty space. It feels like a metaphor for my head.

This strikes me as odd. If I’m defending a mass-murderer, why aren’t there more people here? Why isn’t the public gallery filled to the rafters? I only spotted two hacks on the press bench. Surely there would be national media?

Instead, it’s eerily quiet.

‘It’s quiet today,’ I say to Malcolm.

‘Yes, yours is the only case in the building,’ he replies.

‘What? But there are—’ I check the nearest sign—‘nine courtrooms?’

‘Ten,’ corrects Malcolm. ‘It’s only your case for the whole week.’

‘But… why?’ I look around at this vast, stony space.

‘This court building is only used to try terrorists and foreign criminals now.’

‘But I just met a woman in the robing room. She said that she’s representing a per—’ I catch myself before saying ‘pervert’—‘She’s doing a sex case.’

Concern ripples Malcolm’s forehead. ‘There are no other cases this week. You couldn’t have seen that woman.’

‘But I did. I definitely did. She wore brogues. Her hair was grey. She was posh and funny. You’d recognize her if you saw her.’

Malcolm refuses to meet my eyes. ‘I’m sorry, Miss Dalton, but you’re mistaken. There are no other cases being heard in the court building this week.’

I was so sure she was real.

I despair. It seemed as though I was doing OK, that my mind was mostly intact, and now it turns out that I’m seeing things. My copy of Archbold is tucked under my arm. Its weight is comforting. Later, 22when I get the chance, I will see if the fountain-pen mark is still there. If it is, I’ll know I wasn’t seeing things.

I don’t push the subject with Malcolm. Right now, I need to work out how to represent an alleged mass-murderer with no knowledge of his case. Or at least do a good impression of it. I feel a strange sense of grief for the intelligent, professional woman I used to be. I also mourn the end of my legal career, for it surely can’t survive me absenting myself halfway through the first day of a murder trial.

We’re outside the courtroom again. I recognize the tacky pink curtains.

‘Watch out, Miss Dalton.’

‘What?’

Why am I always so rude to Malcolm?

‘Look around. Water, water, everywhere and not a drop to drink.’

‘What the hell are you…?’

It’s too late. We’re in the courtroom again. Everyone is looking at me, waiting for my next move.

‘Malcolm?’

He’s vanished.

3

I stride up to the front row and take my seat next to the prosecution QC.

‘What are you doing?’

‘Well, my silk isn’t here so I thought…’

‘You thought wrong. This row is for silks and you’re not a silk.’

Humiliated, I move back a row, taking my copy of Archbold with me. Once I’m back where I’m supposed to be, I get my bearings. I’m on the defence side—closest to the jury, furthest away from the witness box.

The prosecution QC is still muttering, ‘In my day there used to be respect for tradition.’

The recipient of this diatribe is a barrister who is of a similar age to me. I can see red hair peeking out from beneath his wig. We sit at the same bench although he is a few paces to my left. Behind him is a team of four; a mix of CPS lawyers and investigating police officers.

I have only one person sitting behind me. This must be my instructing solicitor; another person whose role I understand instinctively. The solicitor is the bridge between barrister and client. They do the background work preparing the case and representing the client in the police station. They also choose which barrister to instruct.

My instructing solicitor wears Buddy Holly glasses and smells overpoweringly of cigarettes. I smile at him. He smiles back, but it’s more of a grimace because he has a habit of wrinkling his nose to keep his plastic frames from sliding off.

‘Miss Dalton?’ asks the QC.

I tug at my skirt self-consciously.

The QC smirks. ‘Have you decided whether your client will give evidence yet?’

I glance back at my solicitor. He returns my gaze, his eyes magnified to three times their normal size by the thick-rimmed specs.24

‘I’m not deciding now,’ I say, each word delivered slowly in case my solicitor signals mid-sentence that I’m saying something wrong.

The QC searches for something on the writing bench in front of him. ‘Just so you know, this is what we’ll be relying on to say your client’s pre cons are related to the bombing.’ He brandishes an amateur publication. Emblazoned on the cover is a black symbol; it looks like a diamond that’s grown legs.

‘Interesting…’ I say.

‘It’s an Odal rune,’ he replies.

‘And?’ I go for disdainful.

‘It’s a neo-Nazi symbol.’

I thought that this would be a game of make-believe, of trying to imagine what a barrister would do in this situation and imitate it. Anything to get me through to lunchtime and then I can get away—away from the threat of institutionalization and, more importantly, away from the responsibilities of the person I’m inhabiting.

But it’s not like that at all. If anything, this is the most natural I’ve felt all morning, glaring back at the QC with steely determination, not rushing to fill the silence he’s left. It’s a buzz and, in spite of myself, I find that I’m enjoying this pantomime. I must have been good at this once. Perhaps I might be in future, and suddenly the pressure of representing the man in the dock settles on my shoulders, accompanying the weight of the woollen gown.

‘Your client has two previous convictions for criminal damage. One for smashing a parking meter and the other for vandalizing a letter box.’

I think about the woman from the robing room, her giveashit persona. It gives me a boost of confidence that dims when I remember she might not exist. I set this worry to one side and try to channel her when I respond.

‘That strikes me as scraping the barrel,’ I say.

The corner of the QC’s mouth twists. ‘When you look at these… magazines that were seized from his address…’ He shakes the pamphlet as though he’s expecting winning scratch cards to come loose.25

‘Being on the distribution list of a magazine proves nothing,’ I say.

He turns to a page. He does it as though at random, but it’s too practised. I suspect he’s kept a thumb in place the whole time he was waving it around.

‘Here, they champion leaderless resistance. In other words, he didn’t need to be a member of the group. They suggest that people who want to be part of the movement partake in any acts of destabilization of the state that they can.’

‘That should be in the dictionary definition of “tenuous”.’

I can see that I’ve gone too far this time. The QC’s sallow complexion sprouts angry red patches.

‘If you want to be like that.’ He turns his back on me.

The negotiation is over. We’ll have to fight it out in front of the judge. I say as much to his junior before turning to my solicitor.

‘Are we calling any other witnesses apart from the defendant?’

His magnified eyes blink. The worried look I get tells me I shouldn’t have had to ask. ‘No.’

‘Just double-checking.’

I look down at the five lever arch folders of evidence in front of me. I flick through until I find the neo-Nazi zines. Pulling one from a polypocket, I approach the dock.

All around the glass box are vertical slits. I get close to one of them and whisper, ‘Are these yours?’

Eades doesn’t look at me, doesn’t register my existence. I look to my solicitor for a bit of backup, but he only gives me a one-shouldered shrug.

‘Court, please rise.’

I hurry back to counsel’s row and remain standing until the judge takes his seat.

‘Are we ready to have the jury back in?’

‘My Lord, I’ve clarified the position regarding defence witnesses. There won’t be any save perhaps for the accused. I’ll review the position as the evidence progresses.’

The judge nods at this. I sit down.26

If I’m carrying on with my tactic of doing whatever the woman from the robing room would do, she wouldn’t have stood for what just happened, wouldn’t have allowed herself to be ‘old-soldiered’ like that.

Emboldened, I get to my feet again. ‘However, there is one matter I wanted to raise, and that is my learned friend’s intention to introduce these highly prejudicial documents and my client’s previous convictions in his opening.’ I wave the rune-bearing zine.

The judge turns to prosecution counsel. ‘Mr Paxton?’

‘My Lord, it has always been a main plank of the prosecution case that Mr Eades’s murderous spree was motivated by his far-right views…’

‘What about his previous convictions?’

I interrupt. ‘Two appearances for criminal damage, My Lord.’

Judicial scrutiny lands on Paxton like a searchlight. ‘What did he get for those? A bind-over and two slaps on the wrist? Really, Mr Paxton, you’ll need better similar fact evidence than that.’

‘My Lord, it’s really about the operation of these far-right cells.’

‘Miss Dalton?’

The searchlight swings around. ‘My Lord, there is one man in the dock and one man alone. If the prosecution’s case is that he was part of a cell, I’m surprised we don’t see them sitting alongside Mr Eades.’

God, that was good. I’m good. I must be good to have that up my sleeve. The judge turns again to Paxton.

‘My Lord.’ His voice is so quiet, it’s almost patronizing. Only a slight vibration betrays his annoyance. ‘These groups operate outwith a chain of command. The prosecution say that he was motivated by the principles of this abhorrent group but acted alone.’

The judge considers the point. ‘Here’s my determination: you won’t refer to it in your opening to the jury, but I will hear further argument after you’ve opened the case.’ He turns to look at me, and the shadow of a wink plays across his face.

‘Very well, My Lord.’ With a shake of his head, Paxton sits down.

A fire of pleasure glows in my chest. I get it now. I understand why I do this… did this. It’s a rush. The back and forth, thrust and 27parry. And I won. I won the point. Not only that, I’m hopeful. I seem to have retained my abilities. That means I must have memories and they will come back, I just have to be patient.

I turn to share a grin with my solicitor, and he returns his half-grimace, half-smile. It’s endearing. Then I look up at my client. He should be smiling too, sharing this moment, congratulating me on my performance. He doesn’t meet my eye. His expression is unflinching. He stares straight ahead.

The jurors return to their seats, and I make a concerted effort not to look at them. My end of the bench is closest to the jury box, meaning they’re only a few feet away, and I don’t want to unnerve them by eyeballing them.

‘Miss Dalton, I understand there are no names or defence witnesses you wish to make the jury aware of?’

‘That’s correct, My Lord.’

‘Very well. Let’s put this jury in charge.’

The clerk who sits at the desk below the judge’s bench gets to her feet. ‘Will the defendant please stand.’

I look behind me. Eades takes his time but does as he’s told. His face doesn’t move. I’m not even sure I’ve seen him blink.

The clerk reads from a piece of paper in her hand. ‘Jonathan Eades, you are charged on this indictment as follows: Count 1, Murder. The Particulars of the Offence are that you, Jonathan Eades, on the twenty-third day of May 1995, murdered Sally Carpenter.’

There are twenty-seven counts of murder. I count every one of them. Each one representing a victim; a whole life ripped away.

There’s also one count of causing an explosion likely to endanger life or property.

Pleas would have been entered months ago. My client needn’t say a word. He just has to stand and listen.

The jurors take the oath, all but one swearing on the Bible. The outlier makes a non-religious affirmation. I take the opportunity to scan the jury. The non-religious member of the jury is female 28and looks to be the youngest. I count five women and seven men, and I’d guess at an average age of forty-five. If my client is indeed a right-wing terrorist, white middle-aged males are probably my best hope for an acquittal. Ideally, they’d be too young to have fought in the Second World War, but old enough to hate immigration and liberalism.

His Lordship gives directions, telling the jury they can’t discuss the case with anyone outside of their number. His words fade to white noise as I scan the lever arch files in front of me, and notice a blue notepad covered in barely legible scribbles. Is this my handwriting? Maybe one of the good things that could come of losing all my memories is the chance to turn over a new leaf and start afresh. I could make new habits. Maybe I could become one of those people with neat handwriting, who trims their cuticles when they need trimming and washes everything up as soon as it’s dirty rather than letting it all pile up at the side of the sink until there’s nothing left to eat off. Something tells me I’m not that sort of person.

As the judge is concluding his directions, my ears prick. ‘Now, members of the jury, I’m going to hand you over to Mr Alasdair Paxton QC, who is going to open the prosecution case.’

Paxton gets to his feet. A little slowly. Perhaps he does that for effect, keeping everyone guessing. There’s a palpable tension in the room now. The jurors are sitting forward. With all the delays and ‘musical chairs’, they’re eager to know what this case is all about.

‘Members of the jury.’ A pause. He knows how to speak, Paxton. His decrepit gown, yellowed wig and doddery posture are at odds with his voice, which is smooth and rich, oozing public school confidence. ‘The prosecution case is that the defendant, Jonathan Eades, who goes by ‘John’, entered a Home Office building on the twenty-third of May last year, where he detonated four bombs before leaving the scene. He injured one hundred and twelve people and murdered twenty-seven.’

Another pause. Let that sink in, he seems to suggest. Twenty-seven. This was a terrible thing, ladies and gentlemen.29

It rankles me. The jury aren’t here to decide on the severity of the crime, they’re here to determine whether my client did it.

So just get on with it.

In spite of myself, I find I’m getting drawn into the drama of the case when I should be focused on my escape plan, keeping my eye on the lunch-break prize. The reality is I’m as curious as the jury to learn what allegations my client faces.

‘It’s at this stage when I give you a brief explanation as to what the case is about so that you can understand the evidence as it unfolds.’

That’s right, you sly bastard. Stick to the facts. No supposition, no comment. No wondering about the motive. Definitely nothing about my client’s passion for the far-right…

‘You must remember that what I say isn’t evidence. Evidence comes from the witnesses who come into court, videos that might be played to you, and any documents that may be put in front of you.’

The jury sits up at the mention of videos.

‘So, what is this case about? What do we have to prove to you?’

4

‘Let’s start with the scene of the crime, shall we?’

With an almost imperceptible movement of his hand, Paxton motions to the barrister sitting behind him. Like clockwork, his junior pulls out a small bundle of laminated photographs which are then handed to Malcolm without a word. Malcolm places a copy before me before distributing the rest to the judge and jury.

I look down at the photo, bracing myself for the horrors of a crime scene: blood splatter, broken glass, little numbered cards. The picture I’m confronted with is nothing like that.

A grey, uninspiring building stares back at me. A municipal eyesore sticking out of a nondescript city centre like a malignant growth. All four sides are perforated with hundreds of rounded rectangles, like a dystopian seed pod.

‘Abbott House,’ says Paxton. ‘A Home Office building in the middle of Birmingham.’ His eyes scan the jury. With a twitch of his mouth that doesn’t qualify as a smile, he adds, ‘Not an attractive building, by any means. Well, that’s sixties architecture for you, isn’t it?’

There’s a smattering of polite laughter from the jury.

‘Twelve storeys dedicated to everything from asylum interviews, processing passport and Visa applications to immigration control, and Criminal Records Bureau checks. The first three storeys were public-facing. The rest were reserved for administration. In other words, this was a building that kept the country turning. It wasn’t glamorous or exciting. This was a building filled with good, honest people doing those workaday tasks that no one gets congratulated for, but everyone would complain about if they weren’t done.’

I’ve got to hand it to him, Paxton can tell a story. And in a trial, that matters.31

‘May the twenty-third was a day like any other. Twenty-seven people attended this dull, grey building expecting to have a dull, grey day. Perhaps they’d been on stuffy commuter trains. Maybe some of them were late getting into work. Maybe they had the windows open, and the fans turned on to try and coax some lukewarm breeze into a sweaty office on a muggy May afternoon. We’ll never know, will we? Because we’ll never be able to ask them.’

With another wave of his hand, Paxton sets in motion the well-oiled machine that distributes another photograph to the jury. This time, the picture is of the waiting area on the ground floor of Abbott House. There’s a reception desk in front of revolving doors and rows of plastic seats bolted onto rails, the sort of thing you’d have to sit on in an airport and then spend the next three days regaining feeling in your buttocks.

‘It was half-past three in the afternoon. Dick Wilson sat at the reception desk, waiting to serve people coming in through the revolving doors.’ As Paxton says this he peers at another photograph. He goes misty-eyed, as though looking at a long-lost relative.

Malcolm waits patiently at the side of counsel’s row for Paxton to hand him the photo. Paxton jumps and looks surprised to see Malcolm standing there. I look over at the jury, willing them to see through his act.

They’re hanging on Paxton’s every word.

Eventually, he pretends to summon up the courage to part with the photo. ‘Dick Wilson is Count 4 on the indictment. He was killed in the blast, instantly.’

Dick’s photo lands on the wooden bench in front of me and I peer into the eyes of a man who looks not a day over twenty-three. I have no idea why they started with this victim. I was expecting Paxton to choose the most beautiful woman. But then I take a closer look at the picture. Dick’s face is marked, the ghost of acne leaving its shadow. He is—was—a bit scrawny, like adolescence came a bit too late and left without having completed the job. He looks like a son. And not the sort you’d be happy to send off into the world. The sort 32you’d fret about. Maybe he’d never find a girlfriend, maybe he’d get mugged walking from work to the train station…

Now I understand why they chose Dick Wilson first.

‘Dick was one of the lucky ones,’ continues Paxton, ‘if you can call them that. He didn’t have to wait under rubble, pressed in by the dead bodies of colleagues you resent getting half as close to you at the Christmas party, didn’t have to have any limbs amputated without anaesthetic. No, some might disagree, but Dick was one of the lucky ones. You can’t say the same for his family, who heard about his death while listening to Radio 1.’

There’s a sharp intake of breath. Paxton pauses. I find myself imagining what it must be like: hearing about a disaster like that on the radio, hearing that it happened at your son’s place of work. Knowing there were fatalities. Hoping, praying that it’s not your loved one who’s on the list of dead bodies. Imagine hoping that they’re just in Casualty. Imagine ringing up every hospital within a ten-mile radius and panicking when your son isn’t on the list.

It must be the worst way to lose someone: not knowing, allowing yourself to hope, and then being sideswiped by the brutal truth when a police officer knocks on your door.

‘Dick Wilson’s job was to greet everyone who came through the door and provide them with helpful information. Where to sit, where to wait, when their appointment would be. From his prime position, Dick would have seen a man walk through the revolving doors weighed down by an enormous sports bag which was slung over one shoulder. He would have been walking lopsided with an unnatural gait.

‘Of course, John Eades walked into the Home Office building without anyone checking his bag. There were no security guards. People just walked in. We haven’t yet descended to the level of barbarism which requires everyone to be searched as though they’re a criminal.’ Paxton removes his glasses and polishes them. ‘Eades didn’t ask Dick for instructions. He strode past the waiting civilians—many of them immigrants—and headed straight for the public conveniences.’33

Paxton stops again. Replaces the glasses.

‘What would he have been thinking, ladies and gentlemen? Looking around at all of those faces, of all colours and creeds…?’

I try to catch the judge’s eye, try and get him to stop Paxton, but before the judge notices that I’m trying to attract his attention, Paxton has already moved onto the next part of the story.

‘No one questioned the bag. Until someone questioned the bag. Just as Eades was about to duck into the gents, out came Kwame Adebayo carrying his mop and bucket. Mr Adebayo was a cleaner employed by the Home Office. His patch was the ground floor of Abbott House, the public-facing part. When Mr Adebayo came across John Eades carrying this enormous sports bag, he asked him what was inside. Eades, in what I’m sure we can all agree was a moment of questionable wisdom, imitated an Eastern European accent and said, “I homeless”.’

Paxton stops to stare around at the jurors, as though he’s sharing a joke with them, knowing the court’s audio recording equipment won’t capture his facial expression.

‘Mr Adebayo simply said “OK” and asked no further questions. What Eades didn’t know at that time was that Kwame Adebayo had gone to let the security guards know that someone was in the building behaving suspiciously.’

Another photo is distributed, this time of a two-cubicle, three-urinal washroom.

‘Once inside, Eades put the sports bag down on the just-mopped floor. His movements were more urgent now—what if he had been spotted? He pulled out two brown-paper bags from a fast-food outlet and put them on the floor, then he extracted a rucksack which he slung over his back. Each of these bags contained a homemade bomb.’

The plosives of that final word echo in this cavernous room, the perfect acoustics for Paxton’s dramatic delivery.

He continues, ‘Eades lugged the sports bag in his grip, only a fraction lighter for having removed the three smaller bags. Think, 34members of the jury, of the effort required here. A heavy sports bag he’s already had to carry through reception. Imagine his back slick with the effort of carrying it that short distance.

‘After removing the first three bags, he went into one of the cubicles and used his boot to knock the lid down. He climbed onto the toilet seat and moved one of the ceiling tiles. Teetering on the U-bend, he bent down and hefted the sports bag to waist height. Then he raised the bag above his head and eased it through the ceiling space. He had to be careful. Inside that sports bag was fifteen pounds of ammonium nitrate and fuel oil, lined with blasting caps. The largest of the three homemade bombs.’

Another pause. By this point, I’m worried. The story is watertight. A lot of supposition in there, but the judge isn’t interrupting Paxton and it’s too early for me to start jumping up and down. Too many interruptions and the jury might think I’m trying to hide something. If the prosecution can prove that Eades walked in carrying the bomb, what possible defence could he have?

‘Next, he pulled himself up through the hole made by the missing ceiling tile. He set to work. Connected to the bomb was a clockwork timer. He set it for ten minutes—he needed time to plant the other three bombs and get out. He checked his watch and memorized the time down to the second. There was a noise down below. Someone opened the door. That was OK, wasn’t it? All they’d see were two brown-paper bags. They wouldn’t look inside, would they?

‘But, ladies and gentlemen, they did. Mr Adebayo, back from speaking to security, opened the door a crack and saw the two brown-paper bags on the toilet floor. Thinking it strange that two of them would be left unaccompanied in a toilet, he decided to take them. What would Eades have seen at that point? Perhaps he lowered his head and shoulders through the ceiling, just in time to see his two paper-bag bombs being taken away by a hand. We know that he finished setting the timer and lowered himself through the ceiling tile, leaving his deadly weapon in place. Next, he needed to get hold of 35those two brown- paper bags. With a rucksack’s worth of explosives on his back, he left the toilet in search of the bombs.

‘Eades began looking in the bins. But he couldn’t see the paper bags. Things were getting serious now. He was running out of time. Having set the timer on the largest of the four bombs, time was literally ticking away. So, he turned and headed back to the toilet. While in there, he returned to the same cubicle and began setting the timer on the rucksack bomb. His fingers were shaking. Maybe with excitement, maybe with nerves.

‘That was when he made the error. He set the timer for three minutes, not eight. We assume they were all supposed to detonate together. It would make sense, wouldn’t it? But now he had a five-minute gap, and he didn’t know how to reset the timer. We don’t know how or why this mistake was made, but it’s clear that his plan was unravelling apace.

‘There was only one thing for it. He took the rucksack out into the main waiting area. He ditched it in a bin and took out matches from his pocket. If he couldn’t get the paper-bag bombs to detonate with the timer, he’d have to do it manually. We can only guess at why the defendant did what he did next. However, the prosecution surmise that Eades assumed Mr Adebayo would not have realized that the two brown-paper bags were bombs. We suspect that he thought Mr Adebayo would have merely performed his duties as a cleaner by putting them in a bin. As you will hear later in this case, Mr Adebayo was much more switched on than the defendant gave him credit for and had alerted security as soon as he found the two unattended bags. It appears that, suspecting that the bombs were now in the bin, Eades threw lit matches into all of the bins in the reception area. Perhaps he thought that looking in bins or rummaging around would raise the alarm.

‘He checked his watch. One minute until the rucksack bomb would go. There were still two bins to light, but people had noticed the first one smoking. People were looking at him. His plan—to draw as little attention as possible—had failed.36

‘So, he lost his nerve. He ran from the building, getting caught in the revolving door—he kept kicking it—until finally it budged. He was free. Then he disappeared.’

Paxton takes a deep breath, lifts a cup of water from the bench to his lips and takes a noisy sip. His speech had been getting faster and faster until he reached the part of the story when Eades left the scene.

I start looking for the cracks in the evidence, trying to spot weaknesses. There’s only one thing that bothers me. The sophistication of the timing mechanism on the bombs is at odds with the shoddiness of the plan’s execution.

How could someone be so callous, so evil, and yet… so incompetent?

It’s a scary thought. I think it’s the fact that someone, anyone, could kill so many people without seeming to know what they were doing. All it takes is enough hatred.

I look over at the jury, a quick glance. A woman in the front row is openly staring at me. I look her way, and she turns her head to avoid meeting my eye.

‘Eades didn’t disappear entirely. The police found out how he left the scene. He ran to Snow Hill Station and got on a train to Solihull. He didn’t pay for a ticket.

‘Meanwhile, on the other side of the city centre, at the Birmingham Children’s Hospital, was Zhu Zhang. She heard the first blast as she was leaving after finishing her shift. It didn’t matter that she’d spent the last twelve hours without so much as a toilet break. Dehydrated with an unpleasant cramping in her stomach, she was probably looking forward to a bath and a pizza. Wouldn’t we all? But when she heard the first blast, her first instinct was to run towards Abbott House. As soon as the first bomb went off—killing most of the people in the waiting area—the building was evacuating. With that many floors and so many people, it was a crush. Then the second bomb went off.’

Another picture is distributed. A dead body, barely recognizable. A set of scrubs can just about be made out beneath the dust.37