1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

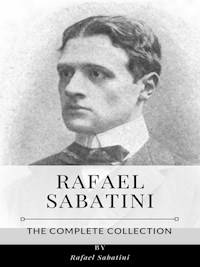

In 'The Tyrant,' Rafael Sabatini weaves a compelling narrative that explores themes of power, ambition, and the moral dilemmas faced by those who seek control. Set against a backdrop of political intrigue and historical context, the novel's prose is characterized by its rich descriptions and swift-paced dialogue, a hallmark of Sabatini's literary style. The author masterfully navigates the complexities of tyranny, portraying the psychological intricacies of a ruler torn between his desires and his responsibilities, thereby allowing readers to reflect on the nature of authority and the cost of dominance. Rafael Sabatini, an Italian-born author who achieved prominence in the early 20th century, was known for his deep interest in history and adventure. His upbringing amid diverse cultures and political upheaval profoundly influenced his writing. Sabatini's experiences with both the old world and the new, combined with his extensive research, lend authenticity and depth to the characters and settings in 'The Tyrant.' His vast literary repertoire often echoes his fascination with the duality of human nature, which is vividly portrayed in this work. For readers passionate about historical fiction and the intricacies of human motivation, 'The Tyrant' is an essential read. Sabatini's evocative storytelling not only entertains but also incites reflection on the nature of power and tyranny. This novel is a thought-provoking exploration that illuminates the fine line between ruler and despot, compelling readers to ponder the moral complexities of governance. In this enriched edition, we have carefully created added value for your reading experience: - A succinct Introduction situates the work's timeless appeal and themes. - The Synopsis outlines the central plot, highlighting key developments without spoiling critical twists. - A detailed Historical Context immerses you in the era's events and influences that shaped the writing. - A thorough Analysis dissects symbols, motifs, and character arcs to unearth underlying meanings. - Reflection questions prompt you to engage personally with the work's messages, connecting them to modern life. - Hand‐picked Memorable Quotes shine a spotlight on moments of literary brilliance. - Interactive footnotes clarify unusual references, historical allusions, and archaic phrases for an effortless, more informed read.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

The Tyrant

Table of Contents

Introduction

When power gathers around a single will, the true contest is not only for a realm but for the souls compelled to live within it.

The Tyrant by Rafael Sabatini is a historical novel from the early twentieth century, shaped by the author’s gift for blending political intrigue with high-stakes personal drama. Best known for his bestselling adventures, Sabatini here situates readers in a vividly realized Renaissance milieu, where shifting loyalties and public spectacle frame struggles for authority. Without relying on strict chronology or documentary density, he crafts a setting that feels immediate and inhabited, using the period’s courts, councils, and marketplaces as an arena for moral decision and tactical maneuver. The result is a stage where private motives collide with public ambition.

At its core, the book turns on the rise of a formidable strongman and the individuals drawn into his orbit—adversaries, opportunists, and those who discover the cost of neutrality. Sabatini builds the premise with efficient clarity: an ambitious ruler seeks to consolidate control, while a capable protagonist must weigh survival against conscience. The experience is one of artful tension rather than relentless violence, favoring strategy, conversation, and reversal over mere spectacle. Readers can expect an atmosphere of mounting pressure, clever feints and counterfeints, and the steady unveiling of character through action as much as through declaration.

Sabatini’s narrative voice balances elegance with momentum. Scenes turn on finely calibrated dialogue and the choreography of entrances, exits, and revelations, allowing power to be measured in who speaks, who remains silent, and who controls the frame. His sentences carry a polished clarity that makes the political intelligible without flattening its complexity. He prefers the duel of wits to the clash of armies, and even when the threat of force looms, the decisive weapon is often intellect. This emphasis keeps the focus on choice, where bravery and prudence, pride and honor, become the levers that shift the story’s course.

The themes are perennial. The Tyrant examines how authority is built—through promise, spectacle, patronage, and fear—and how it is resisted—through solidarity, cunning, and principled refusal. Questions of legitimacy hover over every gesture: What grants a ruler the right to command? When does order become oppression? What risks are justified in the name of stability or justice? Sabatini resists easy absolutes, showing how noble ends tempt ignoble means, and how moral clarity is tested by proximity to power. The book invites readers to consider not only what one opposes, but what one is willing to affirm and defend.

Although set in a distant past, the novel’s concerns feel current. Its portrayal of charisma, propaganda, and political theater will resonate in an age attentive to image and influence. It asks how societies drift into acquiescence, what courage looks like when power is personal, and why private loyalties can both sustain and imperil public good. Readers will find not a tract but a human-scaled study of choice under pressure, compelling because it leaves room for ambivalence. In this way, The Tyrant speaks across time, using history as mirror and caution rather than as distant decoration.

For contemporary readers, the appeal lies in the blend of craft and conscience: a swiftly moving tale that rewards attention to motive as much as to plot. Without revealing its turns, it is fair to say the novel offers the satisfactions of strategy well played, of conflicts earned rather than engineered, and of outcomes that feel both inevitable and hard-won. Those who value character-driven historical fiction, political drama, and the subtle thrill of competing intelligences will find much to admire. Approach it for the adventure; stay for the questions it leaves echoing after the final page.

Synopsis

Set in Renaissance Italy amid fractious city-states and shifting alliances, the story opens with the rise of a formidable duke whose enemies, and even some followers, call him the Tyrant. He seeks to impose order upon a turbulent region by uniting fiefdoms under firm rule. A young gentleman-soldier, skilled and ambitious but untested in high matters of state, arrives at the ducal court to seek employment. The court’s first impression is a blend of pageantry and discipline, where rewards follow usefulness and failure has consequences. The newcomer quickly senses that loyalty here is measured as much by results as by words.

The duke’s council reveals the immediate crisis: a vassal city wavers between obedience and revolt, emboldened by rival lords and condottieri. The Tyrant plans to neutralize dissent through a mix of clemency and intimidation, favoring speed and decisiveness. Our protagonist, singled out for resourcefulness, receives a delicate assignment—carry overtures of peace while quietly assessing the factional currents. He is instructed to win allies, map the loyalties of key households, and prepare the way for firmer measures if diplomacy fails. The mandate is clear: preserve order, minimize bloodshed, and give rebellious magnates a final chance to return to the fold.

Traveling through the countryside, the envoy witnesses both the costs of disorder and the allure of local autonomy. Banditry persists where authority is weak; yet civic pride resists external command. Within the troubled city he meets a noblewoman with ties to a leading faction, intelligent and guarded, whose interests do not perfectly align with any side. Their measured conversations expose the city’s fears of confiscation and the duke’s reputation for remorseless justice. The envoy offers assurances and incentives, pressing for compromise while sensing hidden hands at work. Diplomacy opens doors, but only partially; behind formal courtesies, the crisis deepens.

Whispers of conspiracy surface: a rival captain gathers men in the hills, envoys ride at night, and a courier vanishes with letters that should have reached the duke. The envoy’s caution grows as he learns of a plot that could unseat the Tyrant or provoke a brutal reckoning. He navigates salons and council chambers where every word has weight. The noblewoman, balancing duty and prudence, becomes both guide and test of trust. Their uneasy alliance sharpens his understanding of local stakes. The envoy reports carefully, urging a final attempt at settlement, aware that once swords are drawn, events will outrun intentions.

At court, festivals and spectacles veil hard calculations. Ambassadors trade compliments while the duke, keenly attentive, sifts intelligence and measures character. A private audience reveals his governing method: swift favor for service, swift punishment for treachery, and leniency when it strengthens peace. He authorizes discreet countermeasures—a baited channel for false tidings, a watch placed on wavering barons, and assurances prepared for citizens who might accept terms. The envoy’s candor earns him a closer place in the councils that matter. Yet the Tyrant’s resolve tightens: if reason fails, he will act decisively to spare the country a protracted war.

Negotiations falter as factional leaders hesitate, emboldened by the rumor of outside support. The duke mobilizes, moving with the speed that has made his reputation. An encircling strategy closes the roads, while heralds announce a strict but measured policy for those who yield. Inside the walls, debate turns urgent. The noblewoman presses for moderation, arguing that a fair settlement can preserve dignity and avert ruin. Siege works rise; skirmishes test defenses; and proclamations sow doubt among hardliners. The envoy’s task shifts from persuasion to contingency, seeking to limit harm should the city resist and to prepare a bridge back to order.

The turning point arrives under cover of darkness, when a breach of trust—whether treachery or miscalculation—forces action. The envoy confronts a rival leader whose ambition threatens to ignite the city. In the narrow space between orders and conscience, he must decide how strictly to interpret the mandate he carries. A brief clash and a fraught negotiation follow, with outcomes that reshape loyalties but do not settle the larger question. The episode clarifies the stakes: there will be no painless resolution. Yet, even as events accelerate, the story withholds its final balances, emphasizing choices rather than foreclosing their ultimate consequences.

With the crisis contained but not erased, the duke calibrates justice and pardon to secure a sustainable peace. Offices change hands, guarantees are drafted, and marriages and oaths knit former adversaries into a new settlement. The noblewoman’s future aligns cautiously with reconciliation, while the envoy reflects on the cost of stability. The Tyrant’s power appears firmer than before, yet the narrative acknowledges murmurs of resentment that attend any imposed order. Statecraft here is shown as a sequence of trade-offs—each decision closing one door while opening another, as the region moves from clash toward a tense, provisional equilibrium.

The novel closes on the tension between unity and freedom, authority and conscience. It presents power as an instrument that can end chaos, yet always at a price measured in trust and memory. Without disclosing the final fates of its principals, the story emphasizes how discipline, swiftness, and calculated clemency can bind a troubled land, while leaving unanswered how long such bonds endure. Through a measured progression of missions, councils, sieges, and settlements, the narrative’s core message emerges: ambition can be harnessed to order, but only when tempered by judgment—and even then, its imprint remains, contested and unforgettable.

Historical Context

Set in the high Renaissance, circa 1499–1503, in the patchwork of Italian city-states, The Tyrant unfolds chiefly across the Romagna and adjoining Marches, where the Papal States pressed against the lordships of Forlì, Imola, Faenza, Rimini, Pesaro, and Urbino. This was a landscape of walled communes ruled by signori and condottieri, where foreign crowns—France and Spain—contested hegemony. Courts such as Ferrara and Urbino cultivated humanist polish alongside hard-nosed realpolitik, and the roads teemed with mercenary companies. The papacy of Alexander VI forms the looming horizon, as nepotistic state-building and papal arms attempted to impose order on a notoriously faction-riven region.

Beginning in 1494, King Charles VIII of France crossed the Alps, seized Florence and Naples by early 1495, and triggered the Italian Wars (1494–1559). The League of Venice (1495) forced his retreat after the battle of Fornovo (6 July 1495), but a precedent was set: Italian politics would henceforth be shaped by French and Spanish arms. Louis XII renewed the invasions in 1499, toppling Ludovico Sforza in Milan. This volatility shattered old balances among signori in Romagna. Sabatini’s narrative mirrors the atmosphere of sudden reversals and reliance on foreign patrons, charting how ambitious warlords capitalize on French protection while fearing Spanish countermoves.

Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borgia), pope from 1492 to 1503, exploited the chancery and the papal army to consolidate temporal control in central Italy. His son Cesare Borgia resigned the cardinalate in 1498, was created Duke of Valentinois by Louis XII, and married Charlotte d’Albret in 1499, cementing Franco-papal alignment. Papal bulls of deprivation and military campaigns dismantled petty tyrannies across the Romagna. The novel draws on this nexus of nepotism, ecclesiastical politics, and secular power, depicting how a papal prince could claim legal sanction for conquest while practicing methods—bribery, siegecraft, and sudden coups—that blurred the line between justice and dominion.

Between late 1499 and 1502, Cesare Borgia’s armies, financed by French subsidies and papal revenues, advanced methodically. Imola yielded in November 1499; Forlì fell in January 1500 after a fierce defense by Caterina Sforza. In 1500 he seized Pesaro from Giovanni Sforza and Rimini from Pandolfo Malatesta, often by political pressure before force. The siege of Faenza (1501) culminated in the surrender of the youthful Astorre III Manfredi; Urbino was overrun in June 1502 as Guidobaldo da Montefeltro fled; Camerino capitulated in July from the Varano. The book’s portrait of a tyrant echoes this program: calculated annexations, staged clemency, and theatrical displays of strength woven into a project of regional unification.

Consolidation proved as dramatic as conquest. Cesare appointed the jurist Remirro de Orco as lieutenant to pacify the Romagna with extraordinary powers; within months, roads were secured and banditry curtailed, but exemplary cruelty bred resentment. On 26 December 1502, Remirro was found beheaded in Cesena’s piazza—punished by his master to win popular favor, as Niccolò Machiavelli later observed. Days later, at Senigallia (31 December 1502), Cesare entrapped rebel captains—Vitellozzo Vitelli and Oliverotto da Fermo were strangled that night; Paolo Orsini and the Duke of Gravina perished soon after. Machiavelli’s dispatches (1502–1503) and The Prince (1513) take Borgia as a case study. Sabatini channels these episodes to show state-making born from terror and administrative ingenuity, and its swift undoing after Alexander VI’s death (18 August 1503) and Spain’s ascendancy in Naples.

The Romagnol mosaic comprised dynasties whose fortunes intersect the novel’s themes. The Malatesta of Rimini, the Sforza of Pesaro, the Manfredi of Faenza, and the Montefeltro of Urbino ruled by feudal right, marriage, and condotta. Giovanni Sforza’s marriage to Lucrezia Borgia was annulled in 1497–1500 amid scandal; his loss of Pesaro in 1500 exemplified how papal decrees could unseat a signore. Astorre III Manfredi surrendered Faenza in 1501 and died in Rome in 1502. Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, famed for his chivalry, fled Urbino in 1502 and returned briefly during Borgia’s illness. Sabatini’s characters reflect these houses’ shifting loyalties and the precarious honor code of Italian lordship.

Beyond the Romagna, European rivalry framed every decision. Louis XII captured Milan in 1499; Ludovico il Moro Sforza was taken at Novara in April 1500 and died in captivity in 1508. The French-Aragonese partition of Naples (Treaty of Granada, 1500) collapsed into war: Gonzalo de Córdoba’s Spanish forces won at Cerignola (28 April 1503) and the Garigliano (29 December 1503), securing Naples for Spain. Ferrara, ruled by the Este, aligned carefully; Lucrezia Borgia’s marriage to Alfonso d’Este in January 1502 tied the papacy to the Po valley. The novel situates intrigue and campaign within this chessboard, where marriages, treaties, and sieges served the same calculus of survival.

As social and political critique, the book interrogates the Renaissance bargain between security and liberty. It exposes how nepotism and the sale of offices within the papal court enabled private dominion cloaked in law, and how mercenary warfare transferred costs to artisans, peasants, and towns subject to levies and requisitions. The contrast between princely magnificence and civic fragility reveals class divides, while scenes of summary justice—public executions, confiscations—question the ethics of reason of state. By juxtaposing administrative reform with calculated terror, Sabatini probes the Machiavellian ethic and the vulnerability of republics and signorie alike when foreign monarchies and ambitious captains dictate Italy’s fate.

The Tyrant

PREFACE

It is demanded of the writer of fiction, whether novelist or dramatist, that the events he sets forth shall be endowed with the quality of verisimilitude. What he writes need not necessarily be true; but, at least, it must seem to be true, so that it may carry that conviction without which interest fails to be aroused. The historian appears to lie under no such restraining obligation. Whilst avowed Fiction is scornfully rejected when it transcends the bounds of human probability, alleged Fact would sometimes seem to be the more assured of enduring acceptance the more flagrantly impossible and irreconcilable are its details. And this not merely by the uninformed, who are easily imposed upon by the label of History, but even by those whose activities would appear to connote a degree of mental training at least sufficient to dispel the credulity that lies ever cheek by jowl with ignorance.

Were it otherwise one of the criticisms of this play which found utterance in some quarters on its first presentation in London would not have been that it “whitewashes” Cesare Borgia[1], that it distorts historical records for the purposes of the theatre, and that—either out of venality, or, perhaps, ignorance—it presents a Duke of Valentinois who in nothing resembles the Duke of Valentinois of sober history.

The Duke of Valentinois of sober history is evidently conceived by these particular critics to have been a gentleman with no occupation in life other than the pursuit of murder, incest, and other similar avocations, a prince with so much poisoning and poignarding to do in the ordinary way of business that no time remained him for any of the activities common to a fifteenth-century ruler; in short, a Duke of Valentinois as ludicrous and impossible in fiction as he would have been ludicrous and impossible in fact.

What I mean by this is that the argument of “whitewash” would appear to rest, if it rests upon anything at all, upon the following syllogism: We have been taught that Cesare Borgia in the course of his career murdered, or procured the murder of a number of persons, and that he practised various unmentionable abominations; the Cesare Borgia in this play does not commit or procure, in the course of the events it reflects, the murder of anybody, nor is he shown engaged in vices of any peculiar depravity; therefore this Cesare Borgia is not the Cesare Borgia of history.

The matter would not be worth mentioning at all if it were not for the undeniable circumstance that those who take this view have behind them the authority, if not of historians generally, at least of a certain school of historians, who derive their histories from those of Guicciardini, Giovio, Matarazzo, and a host of others, who, through some four centuries, have been busily re-editing and amplifying the grotesque and sensational tale of Borgia turpitude.

This school—ignoring all contemporary evidences of a refutatory character—represents Cesare Borgia as a monster of infamy, a devil incarnate, a gross sensualist, an inhuman scoundrel without a single redeeming feature. He is accused (without a rag of tenable evidence, either of fact or of motive, upon which to hang the accusation) of the murder of his own brother the Duke of Gandia; he murdered, we are told, his brother-in-law Alfonso of Aragon; he attempted the murder of his brother-in-law Giovanni Sforza, Lord of Pesaro; he poisoned his cousin and friend the Cardinal Giovanni Borgia; he stabbed Pedro Caldes in the very arms of the Pope, whither the unfortunate chamberlain had fled for shelter from his fury; and he is charged with procuring in several ways the death of many others. And these are the least of his alleged crimes. In the same light and irresponsible fashion, without the support of any substantiating evidence, with a cynical disregard of the abundant evidence that might be employed in refutation, he is, together with all his family, accused of wholesale incest and other abominable practices.

Of such a character and quality are the details we are afforded of his misdeeds that if, instead of being the creation of writers who described themselves as historians, Cesare Borgia had been the creation of an avowed romancer, he would have been slain for all time by the ridicule of the public; for such is the conception’s utter lack of verisimilitude that it belongs, not to the realm of sensational melodrama, but to Bedlam.

Elsewhere, and at length—in a “Life of Cesare Borgia,” which is quite frankly a brief for the defence—I have dealt critically and in detail with this curious page of Italian history, examining the sources and applying to the available evidence the ordinary tests. So much would be out of place here, nor is it necessary for my immediate aims.

For the moment, and for the purposes of my present argument, let us admit that the Duke of Valentinois perpetrated all the fantastic crimes and practised all the equally fantastic abominations with which he is charged.