Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: NYLA

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

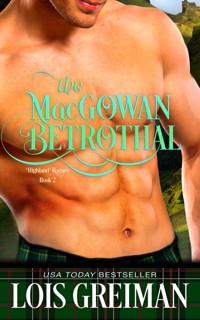

From the bestselling author of award-winning historical romance, Lois Greiman, a classic Scottish Highlander Romance Lachlan MacGowan owes his life to the mysterious and fearless warrior known as Hunter; but his gratitude has never overcome his curiosity. When Lachlan discovers that not only is Hunter talking to an enemy of Clan MacGowan, but is also a woman…. His world is turned upside down! And when the mysterious lass takes a position as nursemaid to the children of his clan's foe, Lachlan appoints himself her escort, and refuses to leave her side, which makes for very interesting days — and even more fascinating nights! Rhona has her own reasons for the guise she's assumed; and refuses to acknowledge the debt that Lachlan wants to pay. If only the annoying and brawny Scot would leave her to her own plans… but Lachlan is on a mission she finds increasingly hard to resist.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 475

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE WARRIOR BRIDE

HIGHLAND ROGUES

BOOK THREE

LOIS GREIMAN

CONTENTS

The Prophecy

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Discover More By Lois Greiman

About the Author

This e-book may not be sold, shared, or given away.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either products of the writer’s imagination or are used fictitiously and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, organizations, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

The Warrior Bride

Copyright © 2002 by Lois Greiman

Ebook ISBN: 9781641973120

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this work may be used, reproduced, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without prior permission in writing from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

NYLA Publishing

121 W 27th St., Suite 1201, NY 10001, New York.

http://www.nyliterary.com

To Leandra Logan,

whose talent is only exceeded

by her unequaled capacity

for listening to me whine.

Grab onto a star, Mary,

but make sure I have a firm grasp

on your coattails first.

THE PROPHECY

He who would take a Fraser bride,

these few rules he must abide.

Peaceable yet powerful he must be,

cunning but kind to me and thee.

The last rule, but not of less import,

he’ll be the loving and beloved sort.

If a Fraser bride he longs to take,

he’ll remember these rules for his life’s sake.

For the swain who forgets the things I’ve said,

will find himself amongst the dead.

Meara of the Fold

PROLOGUE

In the year of our Lord 1535

Though the great hall of Evermyst rang with laughter, Lachlan MacGowan stood in silence amidst the merriment. Aye, friends and kinsmen had journeyed long and far to view the wedding of his brother Gilmour to Isobel of the Frasers. Forbes and MacKinnons and Setons were there. The chief of the fierce Munros, Laird Innes himself, had arrived with his own handsome bride, and stood head and shoulders above the crowd. Even his sisters had joined the throng. Quite bonny they were, at least by the neighboring Munros’ standards. The warlike clan was not known for its fair looks, after all, but for its prowess in battle. Still, a truce of sorts had been crafted between the Frasers and the Munros. And now all were eager to catch a glimpse of the maid who had captured the heart of the rogue of the rogues, but Lachlan was far more interested in another.

From a distant corner of the high-beamed hall, a woman’s laughter could be heard above the melee. Ale flowed in abundance. Upon the high table, grape-stuffed partridges jostled pureed quince and pies of Paris. Guests talked and teased and riddled, but Lachlan remained apart as he searched for the one called the warrior. The one to whom he owed his life.

But try as he might, he saw no trace of the other; thus his gaze drifted to the two young women who stood upon the dais not far away. Isobel and Anora, the Fraser sisters. His brothers’ brides. Twins. They stood together, fair and bonny and bright as a promise. Almost identical, they were, fairylike in their beauty, delicate of face and form. As he watched, they leaned close together, speaking softly. Anora stroked Isobel’s hair, and they shared a smile. It was a simple gesture, and yet it stirred something deep inside him, for it spoke of tenderness and femininity, and a dozen other traits far beyond his grasp. But he knew the truth; they were not gentle maids.

Nay, he did not envy either Gilmour or Ramsay. Hardly that, for these maids would not make their lives the simpler. His brothers had battled for the right to these women. Indeed, Lachlan himself had joined in the fray. Mayhap he would have lost his very life if it had not been for the intervention of the warrior called Hunter.

For a moment he scanned the hall again, but the warrior was nowhere to be seen. An enigma he was, wont to appear during times of battle, and with his brothers’ wives about, there would be many confrontations, for despite their bonny features and willowy forms, they were not the kind to bend easily. They were made of stuff stern enough to wither the stoutest knight. Both brothers bore scars from their delicate hands. Nay, he did not envy his brothers’ fate, for he was Lachlan MacGowan, the rogue fox, and far above battling with a woman. When he wed, it would be to a lass whose hands were as gentle as her countenance.

But then he heard again the sisters’ laughter. His gaze was drawn to them, pulled inexorably across the hall. Each bride wore a delicate chain of silver about her neck, but upon their hips, they wore small daggers and in their eyes was the gleam of trouble. Aye, they were not what he sought in a wife, but God’s mercy, they were beautiful beyond—

“Mooning, Lachlan?”

He refused to jump when startled from his reverie, but turned slowly to find two of his brothers beside him.

“If I did not know better, Quil,” said Ramsay, not glancing at their younger brother, “I would think we had caught the fox daydreaming.”

“Aye,” Torquil agreed, and grinned. The expression was almost as irritating as Gilmour’s. Their mother should have known far better than to birth such a riotous passel of sons. Five of them there were, and each more troublesome than the last. “And daydreaming whilst he stares at your lady, Ram.”

Lachlan kept his own expression carefully stoic. ’Twas never wise to encourage his brothers when they were in “playful” spirits. “I was not daydreaming,” he corrected, “merely contemplating.”

“Then perhaps you should wipe away your spittle and turn your attention elsewhere,” suggested Torquil. Although he would never achieve Lachlan’s musculature, he rarely felt the need to keep his tiresome wit to himself.

Ramsay chuckled. Jealousy, it seemed, was not his weakness. Though Lachlan wondered if he would say the same if he himself had found a Fraser bride, he kept his notorious temper in careful check. Their mother would be unhappy indeed if he initiated a brawl at his brother’s wedding. Past experience assured him of that, so he nodded sagely and relaxed the muscles that bunched like sailors’ knots in his tightening shoulders. “At least I have no scars to show for the attention I’ve showered on her,” Lachlan said.

Ramsay smiled. The expression was serene, natural, ultimately content, and it made Lachlan’s stomach churn, for he himself was less than composed. Indeed, ever since talking to Gilmour some moments before, he felt as fidgety as a baited cat. He turned his attention aside again, searching the crowd. Where was that damned warrior?

“’Tis a small price to pay,” said Ramsay, and glanced once toward his wife. She yet stood with her sister, but Gilmour had joined them on the dais.

“What’s that?” asked Lachlan, turning back.

“The scars,” Ramsay said, and drew his gaze from Anora with an obvious effort. “’Tis a small price to pay to have her by me side.”

“Indeed. She could stab me in the eye with a quarryman’s wedge,” sighed Torquil. “So long as she shared me bed, I’d have no complaints.”

The elder brothers turned in tandem toward Quil. Ramsay’s face, Lachlan noted, was emphatically expressionless. Emphatic expressionlessness was never a good sign in a MacGowan.

Quil tripped his gaze to his eldest brother, cleared his throat, and tried a lopsided grin. “Did I say that aloud?” he asked.

“Aye, wee brother,” said Ramsay quietly. “It seems your mouth outpaces your good sense yet again.”

Quil’s smile widened. “I only meant to say . . . you are a lucky man, Ram.”

“Aye,” Ramsay agreed dryly, “and you will be lucky to remain unscathed if you do not keep a rein on your tongue, lad.”

“’Tis true,” agreed Lachlan. Good sense had rarely stopped the brother rogues from throwing themselves into a fray when the opportunity presented itself, and Lachlan was hardly the exception. “You’d best be careful what you say, Quil, or Anora may yet become vexed and challenge you to a duel.”

Torquil chuckled happily. “Surely you are not saying that Ramsay here allows his wee bonny bride to fight his battles for him.”

Lachlan grunted as he skimmed the crowds again. “Ask him about the scar on his scalp sometime.”

Ramsay said naught, so Lachlan continued. Despite his vow to keep out of trouble’s ubiquitous path, there was a demon gnawing at his guts. “The scar she gave him when she struck him with a bedpost in an attempt to keep him from battle.”

“A bedpost?”

“Aye,” agreed Ram amicably. “It seems me wife was concerned for me welfare even then, but fear not, Lachlan, there is someone just as worried about you—the warrior.” He cast his gaze sideways. “I believe he calls himself Hunter.”

“Ho!” crowed Torquil in a burst of unleashed delight. “A warrior! Interested in the rogue fox?”

“’Tis true,” said Gilmour. Lachlan turned to watch his third brother enter the fracas. God have mercy, Mour sounded just as ecstatic as Quil. “During the battle of Evermyst, Lachlan was rendered unconscious. But the warrior appeared in the darkness.” Mour had been “gifted” with a flair for drama and put his hand to his hip as if grasping an unseen sword. “Like an angel of mercy he appeared and fought off all comers, then, lifting our brother lovingly in his arms, he cradled him against his bosom all the long way to Evermyst.”

Torquil couldn’t have looked happier if he’d been declared the king of bean. “Truly?”

“Aye,” said Gilmour. “Every word. I believe this brawny Hunter fellow has deep feelings for our brother. Indeed, I think he is not—”

“Mour,” Lachlan interrupted quietly. “I’ve no wish to wound you during these festivities.”

Gilmour laughed, looking not the least bit concerned. It was, perhaps, the quality Lachlan hated most about his brothers; they consistently failed to realize their physical inferiority. “Ah, but if you wound me on me own wedding night, me bride will be much displeased, and you’ll be left to explain the reasons.”

“What reasons?” Quil asked, all but breathless with anticipation.

Gilmour motioned for his younger brother to lean close.

Lachlan tensed, but just then he caught a glimpse of the warrior through the crowd and rushed into the mob, leaving his brothers to their gossip. Devil take it! He’d stop these damned rumors here and now!

Concealed in the shadows near Evermyst’s great, arched door, Hunter watched the revelers in silence. He was dressed in dark leather, his face shadowed by a broad-brimmed hat, his hands gloved, his feet shod in black boots that reached just above his knees. He was a warrior, dour and watchful, with few acquaintances and fewer friends.

The Munro was here. Hunter heard his voice boom in the noisy hall, but did not turn. Innis Munro no longer threatened Evermyst. Nay, since he’d lost the battle for Lady Anora’s hand, there had been a truce of sorts between Evermyst and Windemoore, and though that truce did not, in any way include Hunter, he ignored the giant chieftain for a moment.

Laughter echoed to the high beams of the festive hall and Hunter shifted his gaze to find the source. ’Twas Gilmour who laughed. Gilmour of the MacGowans, the bridegroom, the rogue of the rogues. But why would he not be merry? The earth’s treasures were his. Wealth, power, and now this maiden bride at his side. Hunter didn’t glance at her, for he knew exactly how she would appear—just like her sister—fair-haired and bonny and far beyond the likes of him. He tightened one fist and turned to watch Ramsay make his way through the crowd toward Lachlan. Aye, he knew the brother rogues, if not by acquaintance, at least by reputation. Ramsay was the intellect, Gilmour was the charmer, and Lachlan . . . Hunter narrowed his eyes. Lachlan was not a pretty lad. Indeed, by the look of him, his nose had been broken on more than one occasion. He was shaped like a wedge, his shoulders broadly muscled, his hips lean and sculpted. Although all those about him had donned bright ceremonial garb, he wore naught but a free-fitting tunic, open at the neck and tucked into the MacGowans’ traditional tartan. Deep greens and blues, to blend like magic into heather and heath. His plaid was belted by a broad band of leather and held in place by a silver buckle fashioned in the shape of a wild cat’s snarling face.

Lachlan was the fighter.

And yet Hunter had saved him—had arrived just in time to ward off Lachlan’s enemies and carry him to Evermyst. What did the fighter think of that? Would there be trouble? Oh aye. Lachlan had voiced his thanks. But behind the gratitude there had been something more. Curiosity certainly, but also resentment. The rogue fox did not like to be beholden. Perhaps he should have left him to fight his own battles, but—

“So you are the warrior.”

Hunter turned abruptly at the female voice, then shifted his gaze downward, for the speaker barely reached his chest. Indeed, she was as wizened and gnarled as a windblown tamarisk.

“Speak up, lad,” she ordered.

“Aye.” He glanced up once, making certain all was well. He must be cautious, for he was a fool to chance being here at all. “Some call me the warrior.”

“And I am Meara of the Fold.”

“I know who you are.” The words came unbidden and were colored with a shadow of emotion. Hunter held his tongue and said no more.

“Do you now?” she asked, and narrowed her ancient eyes until they were but slits in her furrowed face.

“Aye.” He made certain his tone was casual now, though a thousand unwanted emotions steamed through him. “You are the one who nurtured the ladies of Evermyst.”

“Nay!” Her expression changed. Perhaps there was pain there. Perhaps there was sadness and regret, but perhaps he was seeing naught but what he wanted to see. “Nay. I did not nurture them, but only Anora.” She lifted her much-folded chin and looked him in the eye. “Isobel I sent away at birth, but perhaps you know that too.”

Hunter tightened a fist, then loosened it with a careful effort and focused all his attention on this one adversary, for perhaps, if the truth be told, she was more dangerous than all the other combined. “I have heard the tale.”

“Aye.” She nodded slowly. “Aye, and so you have.”

Hunter drew himself to his full height, looming over the wizened form. “Did you have something to say, old gammer?”

She pursed her parched lips and nodded. Something shone in her eyes, some emotion too deep to guess. “Spirit you have,” she murmured. “Spirit and pride.”

Her eyes were eerie and far seeing, and he dare not let her look too deep. Thus he turned to leave, but she snagged his sleeve in gnarled fingers.

“’Tis said you saved our Lachlan.”

He twisted toward her. “Some say that I did, but if left to his own defenses he would have rallied on his own, most like.”

“Modesty.” Her ancient voice dropped to little more than a whisper. “Aye—”

Hunter yanked from her grasp and turned to leave, but she snatched at his sleeve again. “I’ve a mind to hire you.”

He glanced back at her. “What?”

“You heard me, lad.”

“Hire me? Why?”

“’Tis said you are not afraid to battle. Indeed, ’tis said you are hired to kill in the name of king and country.”

“I have killed,” he confirmed.

She nodded solemnly. “’Tis said you are a great warrior.”

“And why, pray, would you need a great warrior when you are surrounded by the brother rogues?”

“Perhaps ’tis they what need the protecting.”

“What?”

“Trouble comes,” she murmured. “I feel it in me soul.”

“Your soul,” he scoffed, but suddenly he felt an unnatural draft of air. It drifted across the back of his neck, setting his hair on end.

The old woman glanced up as if worried.

“What manner of trouble?” he asked.

She shifted her gaze toward the twins where they stood on the dais. “I know not.”

“Are the maids in danger?”

“Tell me, warrior.” She pinned her uncanny gaze on him, and it was all he could do to keep from shifting his away. “Would you care?”

“Nay,” he said. “I do not even know them.”

“And what of Lachlan? Do you care for him?”

“If you’ve something to say, old woman, do so and have done with.”

“Evil comes to Evermyst.”

“Nay,” he murmured. “Evermyst is all but invincible.”

“Invincible.” ’Twas her turn to scoff. “Naught is invincible, warrior. Surely you know that.”

“What evil?” he asked.

“I know not. ’Tis why I would hire you to abide here with us.”

“Here?” His stomach lurched, his muscles cramped. If there was one place in the world that he did not belong it was here. “At Evermyst?”

“I will make it well worth your efforts, lad.”

Unnamed emotions burned like spirits through him, but in that instant he heard the brothers laugh. He shifted his attention. From across the room, the MacGowans watched him, and then, as if from a nightmare, Lachlan stepped toward him.

“Nay! There is naught I can do for you,” Hunter rasped and, turning, disappeared like a wraith into the crowd.

CHAPTER1

In the year of our Lord 1536

Maybe humility wasn’t Lachlan’s best attribute. True, he was as strong as a bull, as crafty as a fox, and as silent as a serpent, but perhaps he was not quite as humble as he might be. Then again, what did he have to be humble about? He grinned as he pressed aside an elder branch.

Somewhere up ahead was his quarry. Lachlan had been following him for many hours now, and though he had inquired long and searched diligently, he’d learned little. The man traveled alone, he was reputedly a great fighter, and most called him naught but “the warrior.” Lachlan snorted silently.

The warrior, indeed! If memory served, he was not tremendously impressive to look upon, being neither tall nor particularly brawny—although the other had never stood near Lachlan for more than a pair of moments. Indeed, the warrior avoided him, had fled from Evermyst’s great hall, if not from Scotland entirely. Why? If the man had been willing to save him in battle those long months ago, why did he refuse to converse with him?

Lachlan scowled into the deepening darkness. From somewhere up ahead he caught the faintest whiff of smoke on the cool autumn air. He turned his head ever so slightly, concentrating, for he’d finally found the warrior and was not about to lose him now.

The man had started a fire of . . . elmwood, if Lachlan wasn’t mistaken. So Hunter, as Gilmour had once called him, was preparing to dine, and had no idea that he was now the hunted. The great warrior’s instincts were less than impressive, for despite the darkness that had settled in around him, Lachlan knew just where his quarry was. He knew just where he had left his steed, still saddled in the wee dell not far away, and he knew . . . Lachlan canted his head ever so slightly and closed his eyes.

Aye, he knew what the other would eat—mutton and cheese—crowdie, perhaps. He opened his eyes and smiled into the darkness. There was a reason Lachlan was called the fox and it certainly was not for his lithe form. Nay, he’d been blessed with the build of a bullock, but that did not mean he was unable to slip like a shadow through the heather.

Straightening silently, he did so, taking a pair of steps before stopping to listen again. No sound issued from the warrior’s camp, but Lachlan knew just where his prey was.

’Twas lucky for this Hunter fellow that Lachlan meant him no harm. Indeed, he planned the very opposite, for even though his brothers had taunted him relentlessly about the battle of Evermyst, he hoped to finally repay the warrior, to even the score, so to speak.

True, the warrior had been less than appreciative of Lachlan’s thanks, but that didn’t lessen the debt. Hunter had attempted to help Lachlan; Lachlan would help Hunter. It was as simple as that. And perhaps in the meantime the other could learn a skill or two. After all, there was none in the Highlands who could match Lachlan’s ability as a tracker. Barely a sound whispered up from beneath his feet as he stepped forward, and he smiled at the absence of noise. Aye, perhaps he would teach the warrior how to walk so silently. Perhaps he would teach him how to track. And perhaps, if he were an apt student—

Lachlan wasn’t certain whether he felt the point of the blade at his neck, or the fingers in his hair first. But two facts were indisputable, there was a blade and there were fingers.

“Who are you?” The voice was unknown, deep and low and deadly. The knife was sharp enough to draw forth a droplet of blood with the slightest nudge.

Lachlan dare not swallow lest another drop follow the first. He raised his hands and swore in silence. “Put away the blade and I’ll not harm you, friend. I’ve no quarrel with you.” He had tried to learn diplomacy from Gilmour, but perhaps he’d not been the most gifted student, for the other seemed undeterred.

“Then why do you sneak into me camp like a fleabitten cur?”

Silence stole into the woods. “Your camp?” Lachlan asked.

No answer was forthcoming.

“You are the warrior called Hunter?”

“Aye.”

Damnation! “Then you’ve naught to fear from me,” Lachlan said.

There was a moment of quiet, then the other laughed and slipped his knife harmlessly away. “That much is pitiably apparent,” he said, and turned back to his fire.

Lachlan watched him go. ’Twas said the man had carried him to Evermyst. ’Twas said the man had saved his life, but perhaps gratitude was not Lachlan’s primary virtue for even now he could feel his temper rising.

“What say you?” Lachlan asked, and followed the other through the darkness.

Not a word was spoken for some time, but finally the warrior glanced up from his place on a log. From beneath the curved visor of his dark metal helm, his eyes were naught but a glimmer of light tossed up from the fire now and again. His nose guard shadowed his face, and the fine metal mesh attached to the bottom of his helmet did naught but continue the mystery.

“Why have you come, MacGowan?”

Lachlan scowled. So Hunter had recognized him. Perhaps this warrior was not so poorly trained as he had assumed. Indeed, perhaps he was somewhat adept. “In truth,” Lachlan said, remembering his mission with some difficulty, “I have come to return your favor.”

“Ahh.”

The fire crackled, and although it was difficult to see past the fine chain metal that hid the warrior’s cheeks and neck, Lachlan thought he caught a hint of a smile. “Something amuses you?”

“Rarely,” said Hunter, and carved a slice of mutton from a bone.

“Then why do you smile?”

Silence again. Lachlan tightened his fist. Indeed, if he hadn’t come to save this fellow, he would be well tempted to give him a much-deserved pop in the face.

“Leave me,” said the warrior and stood.

“Perhaps you did not understand me,” Lachlan said, his tone stilted even as he did his best to smile. “I wish to repay your favor.”

“Are you so bored, MacGowan?” Hunter’s voice was little more than a murmur in the darkness.

“What’s that?”

“Why else would you come but for boredom’s sake?”

Lachlan straightened his back, but he was quite certain his smile had slipped a notch. “I have come for chivalry’s sake,” he said. “To repay you for—”

But his words were interrupted by laughter.

“For a man who is rarely amused . . .” Lachlan began, then shrugged, as much to relieve his tension as to finish his thought.

“You have come for vanity’s sake,” said Hunter.

“Vanity?”

“To prove yourself me equal.”

Perhaps Lachlan was more vain than he knew, for he had never considered a need to prove his equality. He smiled. “I assure you, you are wrong.”

Hunter watched him for a moment. The fire flickered between them. “I have made me a rule, MacGowan.”

Lachlan waited, but if the other planned to continue, it was a hard thing to prove. And perhaps patience was not MacGowan’s stellar characteristic. “What is that rule?”

“I do not kill a man whose life I once saved.”

The sliver of anger that had wedged into Lachlan’s system expanded a bit. “You think you could best me?”

There was not the least bit of mirth in the man’s smile—only arrogance mixed with a bit of blood-boiling disdain. “Run home to your father’s castle, lad. I have no time to teach lessons that should have been learned long ago.”

Lachlan flexed his hands. “It has been some years since I have been called a lad.”

“Has it?”

“Aye.”

Hunter laughed quietly, as if he shared some private jest with himself. “And therefore you assume you are a man?”

“Would you like to test the theory in battle, mayhap?”

“And here I thought you came to save me.”

“Aye, well,” said Lachlan and tilted his head at the strange twist of fate. “That was before you spoke.”

The warrior grinned, as if savoring his amusement.

“I will allow you the choice of weapons.”

Firelight danced across Hunter’s teeth. They looked tremendously white in the darkness. “Will you now?”

“Aye. What will it be? Claymores? Broadswords? Fists?”

“Did you not hear me rule, MacGowan?”

“Aye. I did. You vowed not to kill any man you once saved. But I assure you . . . You need not worry on me own account.”

“Such an impressive combatant, are you?”

“My opponents have said as much.”

“Any that were not your maidservants?”

“It surprises me that someone has not taught you better manners long ago.”

“Aye. At times it surprises me as well.”

Lachlan nodded. “What do you choose then?”

“Choose?” he asked, and poked leisurely at a burning faggot. “I choose for you to leave off and find another to amuse you.”

“The warrior,” Lachlan said, as if musing to himself. “I have heard a good many rumors about you. Me brother Gilmour has a host of interesting theories, but none mentioned your cowardice.”

“Go away, lad, before I lose me good humor.”

“’Twould not be a fight to the death,” Lachlan assured him. “I would not wound you unduly.”

“Truly? How noble of you.”

“But if you will not choose a weapon I fear I shall have to do so for you.”

Hunter turned toward him, his face barely illuminated by the crackling fire. “And if I choose a weapon as you wish, will you vow to leave me be?”

“Aye. If you do me the favor of a battle it will be me own pleasure to refrain from speaking with you ever again.”

“Very well then.” Hunter rose languidly to his feet. Lachlan tensed and placed one hand on the hilt of his sword. “I choose wits.”

“What’s that?”

“Me weapon,” said Hunter, “is wits.”

Perhaps it wasn’t too late to strangle him and be done with. “Wits,” Lachlan said, “is not a weapon.”

Hunter shrugged. “Maybe not for a MacGowan.”

Anger cranked up a notch in Lachlan’s gut. “Wits it is, then.”

“And you vow to leave at the contest’s end.”

“Happily.”

“Very well then, MacGowan, if you answer this riddle correctly, you may tell all your wee friends that you have bested the great warrior called Hunter.” He said the words strangely, almost as if he were mocking himself. “But if you answer wrongly, you shall act as if you were not bested upon the battlefield. You were not at death’s very door, and I did not save your life.”

Lachlan gritted his teeth, but he managed to nod. After all, if the truth be told, he had already tried to do just that. But the memory kept eating him like a canker, though he was not sure why.

“Then here is your riddle,” said Hunter. “What has neither tooth nor horn nor weapon of any sort and yet has caused more deaths than the most fearsome of brigands?”

Lachlan scowled at him as he ran the riddle around in his mind. What creature was he referring to? The Lord God had given them all defenses of some sort, so perhaps he was referring to a person. Was this some manner of religious debate? Perhaps he had best look deeper. Aye, that was it. The answer was something that could not be seen even with the keenest eye.

Something like . . . the wind or the cold of winter. Cruelty, perhaps.

But nay, they were not quite right. Lachlan glanced at Hunter, but the other was prodding a log into the fire with distant unconcern, as if he had entirely forgotten the contest, as if time held no—

That was it then. Time. It destroyed all things and yet it did not bite nor tear nor pierce.

“The answer is time,” he said. “It causes more death than any other.”

Hunter glanced up from his idle task. “Time,” he mused. “’Tis a fine answer and better than I hoped to hear from you, MacGowan.”

Lachlan’s nerves cranked up. “It has no weapon.”

“You are wrong,” Hunter said. “Time’s weapon is a man’s own age. The answer is vanity.”

“Vanity.” Lachlan repeated the word, his voice a rumble in the darkness.

“Aye,” said Hunter. “Surely you have heard of it.”

“Are you suggesting that I am vainglorious?”

“Nay, I am not suggesting, I am stating it outright. You are vain and you are foolish.”

Lachlan took a step toward him, but the other did not back away. Nor did he reach for a weapon. Instead he raised his chin slightly. “What now, MacGowan? Do you hope to kill me for stating the truth?”

He stopped in his tracks. “I am not foolish.”

“But you admit to the vanity.”

“Because a man knows his value does not mean he is vain.”

“And you know your value?”

“Aye, that I do.”

“’Tis good,” Hunter said. “Then let that be of solace to you on your way to your father’s castle.”

Lachlan drew a cleansing breath. “Mayhap we should begin anew,” he suggested. “I assure you, I did not come to harm you.”

The warrior shrugged. “To harm or help—it matters naught, for you are capable of neither. Now, if you possess the slimmest scrap of integrity, you will honor your vow and leave me in peace.”

Lachlan remained where he was.

Hunter stared at him. “It is not that you are afeared of the dark, is it? Do you need a guide to find your way from me camp?”

“I admit,” Lachlan mused, “that keeping you safe may well be a near impossible task.”

“’Tis good to hear you finally admit your shortcomings.”

“Not at all,” argued Lachlan. “I could keep you safe if I but set me mind to it, but surely there is not a person with whom you have conversed that does not wish to see you dead.”

“Luckily for you, it is not your concern.”

“Nay. It is not,” agreed Lachlan, and, turning into the darkness, vowed never to do another good deed.

CHAPTER2

Vainglorious! Him. Lachlan of the MacGowans. Hardly that. ’Twas that Hunter fellow who was vain. And why? If the truth be told he was probably afeared of fighting. That is why he had refused a battle.

Of course, Lachlan could not blame the warrior. After all, Lachlan thought grimly, watching the sun break over the eastern horizon, Lachlan’s reputation as a warrior had surely preceded him. ’Twas really quite clever of the wee fellow to suggest a riddle instead of a test of arms. One couldn’t blame him for being cautious, but it certainly would have been satisfying to hear the little weasel admit his fear.

Vain! Him! Well, perhaps he was, but at least he had a reason for his vanity, while Hunter . . .

Lachlan snorted. He could best that warrior fellow with one arm disabled, but perhaps beating him into mash would not be considered Christian. Thus he would refrain from that particular pleasure. Still, it would soothe him considerably if he could scare the other a bit. But there again, that too might be considered less than kindly.

On the other hand, thought Lachlan, rising restlessly to gaze back in the direction from which he had just come the night before, humility was surely a godly attribute, so if one looked at the situation in a certain light, perhaps it was his Christian duty to show the warrior the way to humility. Aye, he decided, and smiled into the dawn. Humility may not be his most notable quality, but he was not opposed to helping others find that same saintly attribute.

It was a simple task for Lachlan to find the warrior’s campsite from the previous night, of course. Following him thereafter, however, was not as easy as he might have expected. But then, Lachlan had never liked an easy course. It was the challenge that made a victory rewarding. And too, it was good to know the man had felt it necessary to be somewhat cautious after their meeting.

Lachlan smiled into the darkness. Aye, the warrior was doing his best to cover his tracks now. Indeed, he had ridden his mount down a narrow, swift-flowing burn for some ways, but Lachlan had still managed to find the spot where he’d turned his steed out of the water. Aye, he had found it and he had followed the tracks, and soon he would see his quarry again. Not to exact revenge for the other’s sharp tongue. Nay, that would be churlish, and though he may not be as charming as some, Lachlan liked to believe he was a thoughtful sort.

Content with his thoughts, Lachlan tied his stallion to a rowan that grew beside the burn and glanced upstream.

Aye, the irritating warrior had returned to the rivulet’s edge, but not to ride through it again. Nay, this time he had stopped to water his mount, but he had also made a terrible mistake. He had stopped for the night—beside the burn. It was foolish, for though Hunter had anticipated Lachlan’s approach once, it would not happen again. This time Lachlan would be prepared. He would use all his considerable skills, and he would prove himself the better man.

Unfortunately, it would almost be too easy this time. After all, the campsite was quite near the stream and the sound of the water flowing would cover any slight noise Lachlan’s footfalls might make. But that was Hunter’s mistake.

Easing through the woods, Lachlan held his breath. He was close now, within a furlong for sure, an eighth of a mile, and not too far to use the utmost caution. Thus, he tested the direction of the scant wind and circled noiselessly about so that the breeze trickled into his face instead of onto his back. Not a frond whispered as he passed through the bracken, not a stone was misplaced. Aye, he had been cautious before, but now he was beyond silent as he slipped through the night.

And then, not thirty rods in front of him, Lachlan spotted his prey.

Hunter. He was there, and the situation was even better than hoped for. The warrior was bending over the rushing burn. By the fickle glow of the moonlight, Lachlan could see the man reach into the water. Aye, even though the other was turned away, Lachlan could tell he was washing up. Indeed, his back was bare as he scrubbed at his torso, and what a scrawny back it was!

Lachlan stared in disbelief. Without the padded leather jerkin, the man was as narrow as a sapling. His skin was pale in the deepening darkness and even now, with the moon well hidden again, it was clear that his arms were no brawnier than a strapping lad’s.

Sweet mother Mary, he was pitifully lanky. It was almost a shame to frighten the poor waif, and yet . . . the fellow was disturbingly conceited and Lachlan had made a vow to do his Christian deed and teach him humility.

Thus, quiet as a shadow, Lachlan stepped from the woods. The night was silent but for the rush of the burn. Not a sound issued from his footfalls, and he smiled as he stepped up within inches of his quarry. Ahh, how sweet reven—Christian duty felt, he amended.

“So here—” Lachlan began.

In that instant the warrior spun about. His sword flashed in the moonlight.

Lachlan leapt back. Snatching his own blade from its scabbard, he parried desperately. Their weapons clashed and clashed again. Sparks flew like shooting stars. Lachlan’s sleeve was torn asunder. Pain streaked up his arm, but he hesitated not a moment. Heaving upward, he twisted sharply to the right. Catching the other’s sword near the hilt, he dipped and dragged, and suddenly the warrior’s weapon was spinning into the darkness and Lachlan’s was poised at the other’s throat.

Lachlan paused, breathing hard. “Perhaps a game of draughts would have better suited—” he began, but at that moment the moon broke free of the bedeviling clouds and shone with ethereal light on his opponent’s—breasts!

Lachlan stumbled backward, reeling as if he’d been struck.

“Holy mother!” he rasped and let his weapon drop from bloodless fingers. “Gilmour was right! I was saved by a woman!”

Hunter swept up her sword and with a movement as swift as a serpent’s strike, she tipped her blade under his and tossed it at him. It sang into the air only to pierce the ground not three inches from his feet.

“Take up your weapon,” she ordered, but Lachlan only shook his head.

“You’re . . . a woman.”

“Aye,” she growled and advanced, sword at the ready, “I am the woman who is about to best the great rogue fox.”

If her words were meant as a slur, he failed to realize it, for his head was still spinning.

“But you have . . . breasts,” he said.

“Pick up your sword!” she demanded and stepping forward, fitted her blade below his jaw, just as he had seconds before. “Or shall I kill you here and now?”

Lachlan tilted his head back slightly, but even so he could see her breasts. And they were beautiful, full and fair and moon-kissed in dusky hues. “Kill me then,” he said softly. “And have done with, for I’ll not fight a maid.”

“Damn you!” she swore, pressing forward. “Defend yourself.”

“Nay.”

“Retrieve your sword!”

“I will not.”

For a moment her blade trembled against his throat, but finally she yanked it away with a curse and pivoted about. Lachlan watched her go, watched her bend and lift and pull her tunic over her head and past her waist.

He closed his eyes and remembered to breathe, but his mind was reeling.

“Why—” he began.

“Don’t speak!” she snarled and, retrieving her weapon, stalked back to him. “Or I swear by all that is holy I shall carve your tongue from your head.”

He nodded once. Aye, maybe ten minutes ago he would have gladly welcomed such a challenge, but ten minutes ago she had been a man. Life was indeed full of surprises.

“You’ll tell no one.” Her voice was as deep as the night again, gritted and quiet, but it seemed different now, imbued with a earthy sensuality that he had somehow failed to recognize. Breasts! Sweet Mother. Who’d have guessed—besides Gilmour, of course. Mour had said that Lachlan’s brawny savior had been a woman, had all but driven him mad with the taunting, but—breasts!

“Do you hear me?” she snarled, lifting her sword.

“What’s that?” he asked, and she took a threatening step forward.

“I said, you’ll tell no one.”

Her beauty was hidden from him now, and yet it seemed as if he could see them still, moon-drenched and perfect. “About what?” he asked and tried a smile, but he would never be a success on the stage.

“Damn you!” she swore. “Make your vow or die now.” He was silent a moment. He could feel his heart beating in his chest, could hear his breath and hers.

“Tell me this first,” he said finally. “Why would you hide such beaut—” He paused, searching for words. “Why would you hide your true sex?”

“It matters not,” she said. “Only that I do and that you shall keep it so.”

How could he not have known? “But I owe you me life.” Perhaps he should have been mortified to have been saved by a maid. In fact, when Mour had taunted him with his theory, he had been, but now, for reasons he could neither explain nor condone, he felt some pride for it. After all, she had saved him. Not Gilmour, the rogue of the rogues, nor Ramsay, with the “soulful” eyes. But him. Why? “I owe you,” he repeated, setting aside his thoughts for later dissection. “And I shall repay you.”

“Nay!” Her tone was sharp. “You failed to answer the riddle correctly, thus you agreed to go.”

“Aye,” he said, “but I won the battle of swords and now you shall agree to allow me to repay the favor.”

“Never.” There was passion in her tone. Passion that had been entirely lacking on the previous day, passion that Lachlan would have thought was impossible to awaken from such impenetrable stoicism. “You shall return to Isobel’s castle.”

“Nay, I—” He paused. “Isobel’s castle?”

There was a momentary silence. “To Evermyst, or wherever you choose to go,” she said.

“Why do you refer to it as Isobel’s?”

“You will leave!” she ordered, but Lachlan barely heard her.

“Anora was lady of the keep long before Bel came along. She was raised there as the only child of the old laird and lady. None knew she had a twin until a few months hence.”

She said nothing. He took a step toward her, though she raised her sword in defiance.

“Did you know her? Had you met maid Isobel before she found her way to Evermyst?”

“Mayhap you do not realize this,” she said, her words measured, “but I do not wish to discuss this subject or any other with the likes of you. Nor do I—”

“Who are you?” he asked.

She said nothing.

“How do you know me sisters by law? I’d not seen you at Evermyst but at Gilmour’s marriage to Bel.”

“I am called the warrior,” she said. “Hunter if you must, and no one to be trifled with.”

Trifled with. The phrase brought to mind an entirely different meaning than it would have if she’d said the same thing yesterday. Breasts! Glory be!

“So you came to Evermyst during the battle. But how did you know we were in need, and why did you save me? And—” A thought came to him suddenly. “The warrior . . .” His voice was little more than a whisper. “The warrior at Dun Ard long months ago. When we first found Lady Anora. That was you.”

She neither denied nor confirmed.

“’Twas you who was following the lass. ’Twas you on MacGowan land. You who caused her fall from her palfrey.”

For a moment the world went silent, then, “I will have your vow, MacGowan, or I will have your life.”

“But what of your rule not to wound the very man you saved?”

It seemed a logical point to him and not one to justify the growl that issued from the maid.

“Quiet!”

“You would break your own rule?” he asked. It didn’t seem strange to him that his tone was naught but conversational. He and his brothers had engaged in many such debates while they caught their breath before battling again. “You would break your own rule just to keep your secret safe? Not to mention the fact that I would be dead and—”

“I would slay you just because you irritate me!” she snarled.

“Why—”

“So you should not irritate me!” she said, her voice rising.

He didn’t mean to grin. “In truth, me lady,” he said. “I irritate—”

“Do you always prattle so? Give me your vow and be gone.”

“I cannot,” he said.

Sweeping back her sword, Hunter lunged toward him, and in the same moment Lachlan titled his head back. Her blade swept past him, missing his throat by a breath.

Silence fell over them and then she turned with a snarl and strode into the darkness.

As for Lachlan, he remained as he was. True, he had not believed she would kill him, but when a sword sweeps past one’s throat, one has time to reconsider his judgment. In fact, in that flashing second, one has time to consider many things.

Who was she? Why was she dressed as a man? Why had she followed Anora? Why had she come to Evermyst? And . . . He glanced rapidly about. Where the devil had she gone? Listen as he might, he could hear nothing, and suddenly the idea of losing her caused panic to stir in his gut.

He employed no stealth as he rushed back to his steed, and though it took him some time to find her, he did so finally. She didn’t turn at his approach. Neither did she acknowledge his presence. Instead, she traveled through the darkness as if he were of no more significance than a bothersome midge.

They rode for hours until a glimmer of dawn finally lit the eastern sky. Something rustled in the undergrowth. An arrow hissed into the air, and in an instant a hare lay skewered to the earth.

Lachlan glanced toward Hunter, but she was already unstringing her bow and setting it back in place behind her leather-clad thigh. Throwing a leg over her pommel, she jumped to the ground and pulled a dagger from the top of her tall boot.

He dismounted as well, drawn to the hare. And as he approached it, one singular fact made itself clear. It had been pierced directly through the heart.

“A fine shot,” he said, and she turned abruptly toward him.

“Why do you follow me?”

Her fist, he noticed, was wrapped tight and hard about the hilt of her knife, and the blade was surprisingly close to his chest. He glanced at it, cleared his throat and found her eyes. “Because I owe you?” He had meant to growl back, but the image of her breasts gleaming in the moonlight had somehow unmanned him. Although he was gifted at many things, he had never been particularly adept where women were concerned.

“You do not owe me,” she hissed.

“Aye. I—”

“I absolve you of the debt.”

He remained silent for a moment. “Where are you bound, me l—”

“And I am not your lady!”

“Then what shall I call you?”

“Do not call me. Leave me be.”

“I cannot,” he said simply.

“You cannot.” Her voice was low and quiet. “And why is that?”

“Because you saved me life.”

“Aye,” she agreed, “but just yesterday you were willing to forget the debt.”

“All was different then.”

“Naught was different—”

“You were a man.”

“Me sex makes no difference,” she said, and turned abruptly away. “Indeed,” she added, “if you are wise you will forget what you saw at the water’s edge.”

He didn’t mean to do it, but somehow he snorted, and in an instant she had pivoted back around. Her knife was up again, and her teeth were gritted.

“You have something to say, MacGowan?”

Perhaps he should not, but in fact, he did. “Aye,” he said, and glanced down at her. She was not a small lass, but neither was she huge, standing several inches beneath his own height.

“And what, pray tell, is it?” She gritted the question between her teeth. Nice teeth, he thought. Straight and white.

He shrugged slightly. “The truth is this, lass—wise or foolish, I shall never forget the sight of you.”

She was utterly silent as she stared at him. Beneath the shadow of her dark helmet, he could not quite decipher her expression, but finally she spoke, her voice soft with just a hint of the femininity he had inadvertently discovered. “Why?”

Because she was beautiful. The realization surprised even him, for he had never gotten a good look at her face. In fact, until last night, he had never cared to.

“It is something that a man remembers,” he said simply.

Silence again, then, “Why?”

“Because you . . .” He motioned stiffly toward his own chest. “You were unclothed.”

“I do not see why that should be so amazing. I assume even the notorious MacGowan rogues are unclothed from time to time.”

“Aye,” he agreed. “But that is entirely different.”

“We are not so different,” she said, and turned abruptly away.

“Oh yes,” he argued and followed her through the underbrush as she retrieved the hare by her red-feathered arrow and strode off to her steed again. It felt quite strange discussing such a topic, but then, she was obviously a strange maid. “You can take me word on this, lass, we are completely different.”

She stopped her mount in a small clearing and removed the bridle before facing Lachlan. The dark stallion ambled off, his saddle still in place. “Nay. Structurally, there is little difference between us.”

“You jest.” He let his gaze dip to her chest, but it did him no good, for they were hidden well out of sight. It saddened him to think about it.

“Aye,” she said, her stance stiff. “Little difference atall except for . . . a few small details.”

“Small!” he snorted, then cleared his throat at her sharp expression. “Your pardon,” he said. “But if memory serves . . . and it most certainly does . . . the details were very . . . well proportioned.”

She watched him for several long seconds, then turned away again, leaving him to stare at naught but the quiver of arrows that was strapped across her back. It was crafted of fine leather and stamped with knot work designs that somehow reminded him of deep water conchs all laid in a row. The quiver ended at her lower back, and though her long, bullhide jerkin revealed little, it seemed now that he could discern a thousand idiosyncrasies that belied her guise—the grace of her stride, the sway of her hips, the—

“So you are like the others.”

“Others?” he asked and, lifting his gaze from her backside, suddenly felt the sear of some bitter emotion he could not quite name. “What others?”

“Other men. You are obsessed with a woman’s form.”

“Hardly—”

“You’ve but to be in the vicinity of them and your mind turns to miller’s bran.”

“’Tis not—”

“You are a man trained to battle,” she said and nodded up from her task of collecting firewood. “Aye, you have had some tutelage. And despite my initial suspicion you are not completely inept. But one sight of me chest and . . .” She scowled as if baffled, as if talking to herself. “I could have killed you with ease.”

“Not . . .” He grimaced, remembering. “Not with ease.”

She laughed. “Are you daft? You practically begged me to slit your throat. And why? Because me chest is conformed a bit differently than yours?”

“Nay, ’twas not the reason. ’Tis simply because . . .” Very well, perhaps he had been a bit discombobulated. “You are the fairer sex.”

“Fairer!” Anger punctuated the word. Her teeth were gritted and her hands formed to fists. “Fairer than what?”

“I meant no insult, me l—”

“I am not your lady!” she growled.

He almost stepped back a pace at the force of her emotion. What had he said to make her so irate? “’Tis simply that me mother taught me to revere the fairer . . . the female gender.”

“Well your mother was a fool!”

If a man said the same he might well be compelled to teach him better manners at the end of his sword, but now he merely scowled. “Me mother is many things,” he said. “But a fool, she is not.”

Silence fell between them.

She tilted her head. “You cherish her?” she asked. Her voice was strangely soft and he nodded in some confusion.

“Aye. Certainly. And you?” he asked, but she had turned away already.

“You change the subject,” she said. “Because you know I am right. Men make fools of themselves for no reason more substantial than the sight of a woman’s body.”

“’Tis not true.”

She laughed. “Oh, aye, it is and you well know it. One glance of a woman’s bosom and all thought flies from your head.”

“I was merely surprised,” he countered.

“Surprised! You looked as though you’d swallowed your heart. Had I not wished to kill you I would have laughed at the sight of your face. Tell me, MacGowan, have you not seen a woman’s breasts before?”

He mouthed something, but no words came for a moment.

“Well?”

“Of course,” he said. “I’ve seen . . . scores—”

“Then why did you all but swoon at the sight of mine?”

“’Tis a far cry from the truth. In fact, I barely . . .” He wasn’t sure, but he may have winced at this point. “. . . noticed.”

“Truly,” she said, and scoffed. “So I could disrobe this very instant and you’d not be the least distracted.”

“Nay I—” he began, but the possibilities suddenly penetrated his brain. Beneath his plaid, his interest raised its horny head. “Are you considering it?”

Hunter’s gaze held his and then, slowly, irrevocably, she lowered her hands to the buckle on her scabbard. It came away in her fingers and fell to the ground.

Lachlan stared like one in a trance, and then, like a butterfly, her fingers moved the slightest degree. For a moment, he was almost aware of danger, but already the narrow blade had been slipped from the hidden sheath and was flying through the air. He heard the hiss of its passage as it skimmed past his ear and sped with vicious intent into the tree behind him.

He turned to glance at the reverberating hilt, then back at her.

“Go back to your mother, MacGowan,” she growled, and turned scornfully away. “There are dangers afoot and I have no time to keep you safe.”

“If you would cease trying to kill me there would be no need to worry for me safety.”

“Trying to kill you!” she scoffed, and laughed. “If that were the case, laddie, you would already be dead.”

He smiled. “I think not . . . lassie.”

“I am not—”

“Not a lassie, not a lady. What are you then?” he asked, and stepped up to look down at her from a closer angle. “For you surely are not a man.”

“Nay, I am not,” she hissed. “For I have more important things to do than preen my fragile ego.”

“And what things might those be?”

“’Tis none of your concern, MacGowan, but I’ll not have your death on me hands. Go home to your clansmen. Tell them you bested Hunter the great warrior if you like.”

“Why would me life be endangered if I remained with you?”

She watched him for a moment, but finally she turned away with a shrug. “I travel south, down to the borderlands. They have no love for bonny Highlanders who wear their plaids like a badge of honor.”

“Why?”

“Are you so coddled as to have no knowledge whatsoever of the world? There is no love lost between England and Scotland. Surely you know—”

“Why do you travel south?” he corrected.

“’Tis none of your concern.”

“Perhaps ’tis true,” he agreed. “Nevertheless, I shall remain with you until me debt is paid.”

“So you insist on continuing this foolishness until you have saved me life?”

“Aye.”

“Then I shall threaten me own life and you . . . in your manly way, can convince me to go on living.” She glared up at him. “Then we can have done with it here and now.”

“I think not,” he said and turning, pulled her knife from the tree behind him. Holding her gaze, he sent it shivering past her toe and through her boot’s exposed sole.

She didn’t flinch. Indeed, her gaze never left his. Even when she bent to pull the blade free, she continued to watch him.

“Aye,” she said, and straightened slowly, “you’ve had some tutelage, MacGowan. Mayhap the border reivers will not find you such easy fodder after all. It seems I shall find out, whether I want to or not.

“You skin the hare. I’ll kindle a fire. We can bed down here until nightfall.”