9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

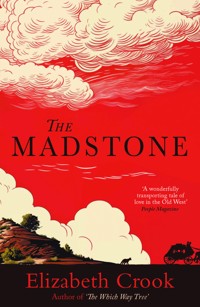

- Herausgeber: Bedford Square Publishers

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

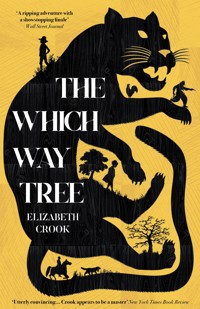

When a panther attacks a family of homesteaders in the remote hill country of Texas, it leaves a young girl traumatised and scarred, and her mother dead. Samantha is determined to find and kill the animal and avenge her mother, and her half-brother Benjamin, helpless to make her see sense, joins her quest. Dragged into the panther hunters' crusade by the force and purity of Samantha's desire for revenge are a charismatic outlaw, a haunted, compassionate preacher, and an aged but relentless tracker dog. As the members of this unlikely posse hunt the giant panther, they in turn are pursued by a hapless, sadistic soldier with a score to settle. And Benjamin can only try to protect his sister from her own obsession, and tell her story in his uniquely vivid voice. The breathtaking saga of a steadfast girl's revenge against an implacable and unknowable beast, The Which Way Tree is a timeless tale full of warmth and humour, testament to the power of adventure and enduring love.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Praise for The Which Way Tree

‘Not since True Grit have I read a novel as charming, exciting, suspenseful, and pitch-perfect as The Which Way Tree. Elizabeth Crook’s new book is winning from first page to last’ Ron Hansen, author of The Kid and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford

‘This book is the stuff of legends, tales told for a hundred years around Texas campfires. Written in a form that is historically accurate and yet feels painstakingly intimate, The Which way Tree is unlike anything I’ve read before’ Attica Locke, author of Bluebird, Bluebird

‘Elizabeth Crook has created a book of marvels. Its comedy is steeped in the hardscrabble tragedies of a wilder old America. You will even catch an echo of Twain’s wit in the picaresque narration’ Luis Alberto Urrea, author of the national bestseller The Hummingbird’s Daughter

‘A fast-paced story resonating with rich characters and mythic elements that come to us as folklore that mustn’t be doubted’ Daniel Woodrell, author of Winter’s Bone and The Maid’s Version

‘Elizabeth Crook has invented a brilliant way of seeing the old Texas frontier: at very close range, through the eyes of a wise-beyond-his-years seventeen-year-old boy and the sister whose defiant quest he joins. The result is a small-scale masterwork, richly detailed and beautifully rendered’ S C Gwynne, New York Times bestselling author of Empire of the Summer Moon

‘When I began to read this book its unique voice appealed to me immediately. Elizabeth Crook has written a beautiful novel with wonderful characters’ Robert Duvall

‘A gripping page-turner, readers will want to devour The Which Way Tree in one sitting’ Sadie Trombetta, Bustle

‘The Which Way Tree is one part Track of the Cat, one part True Grit, and one part Tom Sawyer, a ruthless pedigree for a novel that displays human nature in its most beautiful form – a marvel’ Craig Johnson, New York Times bestselling author of The Western Star, a Walt Longmire mystery

‘Poignant and plainspoken… Crook crafts Benjamin’s narration beautifully, finding a winning balance between naivete and wisdom, thoughtfulness and grit’ Publisher’s Weekly

‘Recalls Cormac McCarthy’s horseback meandering and keen eye for terrain and flora in The Crossing. There are also obvious echoes of True Grit, though Sam is even more fiercely single-minded than Mattie… An entertaining picture of harsh, stark life in the Old West’ Kirkus Reviews

‘Readers new to the Western genre will be hooked if they start with this compelling novel’ Emily Hamstra, Library Journal, starred review

‘This is a story of unremitting deprivation allayed by unexpected kindness, with a dangerous chase motivated by love and suffused with humanity’ Michele Leber, Booklist

‘Crook had me from the beginning. The Which Way Tree is unlike anything I’ve read before… The action is suspenseful and fast-paced; the narrative flow seamless; the dialogue often laugh-out-loud funny; Benjamin’s developing relationship with the judge through his letters is sweetly affecting. Crook’s research is evident in the period details, rhythms of speech, and Texas history… The Which Way Tree is an enthralling adventure, a Texas fairy tale in the truest sense of that term – not a Disney version, but a Brothers Grimm, Old World fairy tale for the New World’ Michelle Newby, Lone Star Literary Life

‘It’s impossible not to think of icons of the frontier Texas subgenre that have mined the same vein. Among them: Charles Portis, True Grit; Larry McMurtry, Lonesome Dove; Fred Gipson, Old Yeller. While set in the 1930s, Joe Lansdale’s The Bottoms also has a very similar feel. It’s a notable stable of companions, and you will hear more of this fine addition to the list’ Rod Davis, Texas Observer

‘The Which Way Tree is the latest from Austin author Elizabeth Crook, who manages in it the striking feat of not only capturing the voice of a nineteenth-century youth as honestly and compellingly as Mark Twain did but also having her Texas Huck recount a Moby Dick-like pursuit across Texas in which the White Whale is a malevolent mountain lion and its Ahab is a girl it mauled while killing her mother’ Austin Chronicle

‘The Which Way Tree packs an epic feel into 272 pages, stretching from the chaos of post-bellum Texas to the comparative civility of the early twentieth-century… It’s a ripping good tale of vengeance, a fast-moving yet epic story’ Austin American-Statesman

‘It’s a story that hooked me from the get-go, and when Benjamin finishes his last letter to the judge, I wanted the story to continue… Fans of Paulette Jiles’s News of the World will be gratified to find another well-told, old-time Texas tale of big adventure and big characters’ Emily Spicer, San Antonio Express News

For my grandparents

Howard Edward Butt (1895-1991)

and

Mary Elizabeth Holdsworth Butt (1903-1993)

Testimony of Benjamin Shreve

Before Grand Jury of Fifteen

Home of Izac Wronski

Judge E Carlton Presiding

18th District

County of Bandera

State of Texas

April 25, 1866

As Recorded by Alfred R Pittman

Having been duly sworn, state your name.

Benjamin Shreve.

State your age.

Seventeen years, sir.

Where do you live, Benjamin?

Over on Verde Creek. Near Camp Verde.

All right. You may stand there. It’s crowded in here; I apologize for that. My name is Judge Edward Carlton, and this is Alfred R Pittman. He’ll be writing down what you say before the grand jury today. Speak clearly. If he asks you to repeat something, then repeat it.

Yes sir.

You can hang your hat there by the door.

I prefer to hold it, sir.

All right, then. Do you know why you’ve been called here?

On account of the men I found dead on Julian Creek.

That’s correct. We believe you were the first to see the bodies and that you may have seen one of the men who hanged those gentlemen. We realize this happened three years ago and justice has had to wait out the war. So your memory on the particulars might not be clear. Simply recall what you can. Don’t make anything up. If you don’t remember, say you don’t remember.

I will remember, sir.

Very well. Now, the basic facts of the murders have already been established, but we’re trying to verify the names of those who took part.

I can tell you Clarence Hanlin was one that did, sir.

I’m not looking for your opinion, Benjamin. I’m looking for your testimony. That means what you saw, not what you think. Answer only the questions I ask you. Now. What were you doing on Julian Creek that morning when you discovered the bodies?

Hunting, sir.

Julian Creek is quite a few miles from Camp Verde. Why were you not hunting closer to home?

There was no game closer to home. The Sesesh soldiers at Camp Verde had killed it all off for theirselves and their prisoners down in the canyon.

How did you get to the Julian that morning?

Horseback, sir.

Were you alone?

Yes sir.

What time did you leave your home?

I suppose about a hour or so before daylight. I recall I rode in the moonlight.

And your intention was to hunt on Julian Creek?

My intention was to kill the first game I come across. It was a deer near the Julian. I fired and missed it.

What happened after that?

I pitched a fit, sir. Dismounted and cursed, and then right away wished I weren’t behaving in such a manner.

For fear you would scare off game?

For fear of Indians and Sesesh and bushwhackers and vigilantes and whatnot. It was loud and dangerous behavior, sir.

Benjamin, the men in this room, some of whom you probably know, are of various persuasions on the late war. You would do well to refrain from name-calling.

Yes sir, I know one… two… three… four… five of them here that me and my father sold shingles to. That one by the door there—

Don’t bring politics into this.

No sir, I won’t. But it was Sesesh that done in the men I found dead.

It is true that Confederate major William J Alexander from Camp Verde, whereabouts unknown, is currently under indictment for murder and highway robbery. We’re trying to ascertain which of his men took part in the hanging of the eight travelers you found dead.

Clarence Hanlin was one, sir.

I know that’s your testimony. But if it’s true, we have to get to it in a logical way. Simply answer my questions.

Yes sir.

So you fired at the deer, and missed, and pitched a fit. What happened next?

I heard coyotes yipping and I thought it was Comanches. I tied my mare in the brush and went a distance off and laid down flat where nobody could’ve seen me in the grass. But the longer I laid there and listened, the more I thought, that is not Indians, that is actual coyotes. I figured maybe I’d shot the deer and wounded it, and it had run off and gone down and now the coyotes was closed in and devouring it. So I thought to go and investigate and see what they was up to. I went on my belly on the chance it was Comanches in fact and not coyotes. And that was when I come across what I seen.

As precisely as you can, describe what you saw.

Clarence Hanlin and a pack of coyotes under a clump of scrub oaks, sir. Some ways from the creek. They was in dusky light of the morning, amid prickly pear, on rocky ground, and the coyotes was lighting out because Clarence Hanlin was waving a stick and yipping at them with a yip like he was one of them. He was spooking them out. It was a puzzle to me why he did not shoot them if they was bothering him. He had a gun. But it appeared that he—

You had not, at that time, ever seen Mr Hanlin before – is that correct?

Not exactly correct, sir. I’d seen soldiers coming and going on the roads near Camp Verde, and I believe I’d seen Clarence Hanlin amongst them, as I’d noticed he had a eye that drooped. He had a distinctive look, sir. It was not a pleasant look. He was not homely, but his looks was against him and not right.

Gentlemen, can we please have no snickering? Alfred, I hope you’re getting everything down. I want the details recorded. All right, Benjamin, you saw a pack of coyotes and a man, whom you thought you might recognize as one of the Confederate soldiers stationed at Camp Verde, but whom you did not, at that time, know by name and with whom you had never conversed, waving a stick at the coyotes in the apparent effort to scare them off. Is that right?

Yes sir. And yipping at them, sir. It was a odd thing, to my thinking. There was a doglike thing about it, sir.

Are you casting aspersions?

If you mean am I insulting the man, no sir. I guess you could say he sounded a bit like a pig, too, sir, if you wanted to cast what you said. A aspersion. It would not be off the mark. I will put it this way. It was a weird noise he made to fuss at them coyotes. Rather spooked me. Then I seen him squat down like he was fixing to pluck up firewood or some such. There was plenty of broken limbs laying about. But what he plucked up was not firewood, it was a arm. And then I seen that it was attached to a body. And then I seen other bodies.

Pause there. Where were the bodies?

All about at his feet, sir. Scattered, I would say. Maybe a dozen of them.

For the record, there were eight bodies.

They looked like more than eight to me, the way they was strewn. But eight’s on the mark if you say so. I was twenty yards off, or more. The light was feeble, on account of the sun was not full up. And now that I think on it, I suppose my first idea was the bodies was logs and branches, and nothing amiss. So how many of them there was, I did not contemplate on at that time.

There were eight dead, precisely. We have their names. Some of these men here in this room were called out from town to help bury them. Now continue. What did you do when you saw the bodies?

I tried to figure it out like this: here is these bodies and these coyotes and Clarence Hanlin with his stick and his yipping. So—

Clarence Hanlin, whom you did not yet know to be Clarence Hanlin, but with whom you would later, I take it, have some familiarity?

That’s right, sir. At that time I known him for a man with a droopy eye, in a Sesesh outfit, who I thought I might have seen before on the road near Camp Verde. So I figured the coyotes was trying to feast on the bodies, and Mr Hanlin, the Sesesh, was scaring them off. That’s how I seen it, the best I could figure. But then it come to me that I had more to figure, because what was the bodies doing there? I figured maybe Comanches was there and killed the men the coyotes was trying to feast on, and this Sesesh come along, and though he was not friendly to look at, he was protecting the bodies. But hold it there, I thought. Because then I seen him take a object from the jacket of one of them on the ground. He took from one, and rose a step, and poked at another with his stick, and squatted and took a object from that one, too. He was looting the dead, sir. He was taking what he could find. He went from pocket to pocket, searching for valuables to pinch and pilfer. He had a satchel strapped to his side, and he put things in that. I was fearful to breathe, sir. I figured if he should see me witness him, he would come after me. I did not so much as twitch. He turned my direction at one time and did not see me, but I got a good look at him. His gaze was oddly fixed, sir. He had a harsh stare. When I seen that, I rose to my feet and took to my heels in a hurry. I made my way to my mare and rode as fast as she would take me back to my home.

And why did you not report the crime you had witnessed?

It was not easy to know what was a crime, and what was not, with so much mischief afoot.

I understand your parents are deceased?

Yes sir.

For some time now?

Yes sir. I live alone with my sister.

Very well. Now. About your subsequent encounters with this man. Tell me about those.

Well, that’s a long story. He wanted to do me in. Me and my sister both.

He wanted to kill you? Because of what you had witnessed?

No sir. Because of a thing that happened. I’d rather not be made to speak of it, if that’s a option.

It is not an option, Benjamin. Why did he want to kill you?

Well, sir. I guess it was on account of my sister had shot his finger.

Shot his finger?

Shot it off, sir.

You’re saying she shot off one of his fingers?

One and a portion, sir.

Gentlemen, hold your amusement. The boy will explain. Benjamin, will you recount the circumstances?

Some time after what I seen on the Julian, my sister and me was sitting in a tree with a goat staked out on the ground to entice a panther. It was my sister’s wish to kill the panther but Mr Hanlin got hisself in her aim.

She shot him by accident?

No. He provoked her, sir. He was hollering and advancing so she shot at him, and rightly so, if you ask me, although I did not think so at the time.

Can I assume he had a reason to be hollering and advancing?

I suppose, sir. She was hollering at him.

I see. Benjamin, I have at least a dozen other people I need to question today, so I don’t have time for digressions. But if Clarence Hanlin is a man prone to committing violent acts without provocation, that would be helpful to know. Would you say that’s the case?

I would say there was some provocation by my sister only if hollering is provocation. But before her provocation he was provoking of her by the needless act of stabbing a camel, sir.

One of the camels stationed at Camp Verde, I presume.

Yes sir. So I would say the first provoking act was on the side of Mr Hanlin, done by him. The camel was decrepit and broke down, and Mr Hanlin jabbed it a fair number of times in the hump as it was not moving as fast as he wished it to. It made loud and fearful noises whilst being stabbed, sir, and fell to its knees – a monstrous end for a beast come all the way from Egypt. My sister would not sit for it, and being as she was in the tree and had a pistol, and the panther had not come hisself to get hisself shot, it was a poor time and place for Mr Hanlin to be stabbing the creature in such a way. I will give you the short of it if that is what you want. My sister—

I’m afraid I don’t have time even for the short of it at the moment. I need information specific to Mr Hanlin’s guilt or innocence in murder and his current whereabouts. How many times did you have contact with him after seeing him on the Julian?

It was ongoing, sir, after what my sister done to his finger. He was tracking us for two full days and a portion of another. On occasion he gave chase. There was words spoken. There was shots fired.

I’m uncertain if you’re providing a deficit of information or a surplus, son, but I’m getting no closer to what I want to know. Can you stick close to the point?

Clarence Hanlin was one that done in the men on the Julian, sir. Hanged and robbed them. He told me by admission of the hanging and I witnessed the robbing. If that’s what you’re in search of, then there it is, sir. The very, very short of it, sir. You have my word on it.

He told you of the hanging?

Yes sir. In some detail, when he caught up with us. He told me he’d string me up, too. Said he’d string up my sister right alongside and watch our necks pop. He was a terrible pest, sir.

And your sister heard this confession and threat also?

Yes, she did. It led to a great deal of conflict. She is a person of uncommon temper.

I will need to have her testify.

She won’t do that, sir. She’s cat-marked and poor to look at. Also mulatto. Her mother was a Negro. She won’t come.

I’m to understand she had a different mother from yours?

Quite different from mine, sir. However, both passed. Alike in that respect, sir.

How old is she?

Younger than me by two years. Fifteen at the present time. Twelve when she done what she done about the finger.

I see. Can you read and write?

Efficiently. I have twice read the whole of The Whale, about Moby Dick. I have read Malaeska: The Indian Wifeof the White Hunter. And I have read two novels of the Waverley brand. They was all given to me by the Yankee prisoners down in the canyon. I tossed them a ear of corn and up come The Whale. Fell at my feet. And next day I—

Do you post and receive mail?

No sir. I have not in the past. The Camp Verde post office is shut down now. That whole place is a shambles and looted. I could receive mail at the post office in Dr Ganahl’s home at Zanzenburg, which is not far off from my home. However, he was Sesesh, and remained so, and has fled to Mexico, and I do not know if—

We’ll settle on the post office at Comfort. I want you to write a full account of every encounter you’ve had with Clarence Hanlin. Write in detail and be frank. I’ll be back in Bandera in three months and at that time I’ll need to render my recommendation to this grand jury. I will be questioning others about this case in the mean-time. But because you have had personal interactions with Mr Hanlin your statements are essential. It’s our job to make sure justice is done in these crimes of Confederate soldiers against civilians of Union sentiment. A big part of that job will be yours. I want you to write a clear statement of who you are, who your parents were, who your sister is, and describe every brush you’ve had with the individual you know as Clarence Hanlin. Remember that this is a testament and you are under oath to be truthful. Then I want you to deliver your report to the Comfort post office. The postmaster will see that it finds me. If I have further questions I’ll put them to you in writing and send them to Comfort. Do you often go there?

Yes sir, I do on occasion, to sell furniture I make.

All right. Before you leave now, let me be clear on one thing. I presume you have not seen the man you refer to as Clarence Hanlin in the three years since the encounters we’ve discussed?

No sir.

And where, exactly, was he when you last saw him?

The Medina, sir. Somewhat north of here. He went round a bend. Swept away.

Swept away?

In a gullywasher. Off he went in the gullywasher and I’ve not seen hide nor hair of the man since that time.

This is unexpected. Do you presume him dead?

I’d be spooked if he was not dead, sir. It would be unnatural.

This is certainly news. We may finish with Mr Hanlin sooner than I thought. You are certain it was he?

None other but him, sir.

I see. Well. This only increases the importance of your job. Evidence is our bulwark against chaos. If Clarence Hanlin is guilty and living, he has to be found and convicted. If he’s deceased, he has to be proved so. He can’t simply be presumed so and allowed to go free when eight men traveling to Mexico were captured, robbed, and hanged. I want you to write the account I asked for and deliver it to Comfort as I said. I want all the details on record.

Sir? I have no pens and papers.

Izac, can you spare Benjamin quill and paper and a pot of ink?

Yes, Your Honor. I can.

Benjamin, I assume you’re heading home on horseback?

Yes sir.

You’re aware the Comanches have been raiding over in Blanco County?

Yes sir, I’m much aware of it. And Mr Berry Buckalew killed on the Seco. My father and me once cut shingles with him. And Mr Hines, that lived at the Mormon camp, done for at Tarpley’s Crossing. I know of it all. The troubles with Kickapoos, too. I’m well aware, sir.

Is your sister alone at your home?

Yes sir.

Take care on the road, will you?

Thank you. I always do, sir.

Dear Judge,

Here is my statements to what you asked. However, it is not all of them as there is more. I will send more later.

Yours kindly,

Benjamin Shreve

MY TESTAMENT

WHO I AM

I am Benjamin Shreve.

WHO MY PARENTS WAS

My father was Alton Shreve. My mother was Millie. I guess her name was Millie Shreve after she married my father. I don’t know what it was before that. My father always just called her your mother. I did not know her personally as she died shortly after my birth, which event took place in the winter of 1849. I have been told by others she was a good woman and pretty to look at if a tad bit flat in the face. Before I was born, she and my father come here from Duck Hill Mississippi and my father built a house and was making acceptable money in shingles which at that time was starting to be a good living in these parts, if hard work. When I was born and my mother passed, my father had a impossible time taking care of me and cutting shingles and making hauls to market. I was left to squall much of the time, what choice did he have in the matter. I suppose there was nights he wished the Comanches would hear and come take me.

WHO MY SISTER IS

My sister is Samantha Shreve. You asked me to be frank so I will tell you she is my half sister, as her mother was a Negro and mine was white. On occasion I call her Sam, which I think she prefers though I have no reason to know so, as she has never said so. She is fifteen years old, scarred in the face by a panther that killed her mother when she was six. She is scrawny and nothing to look at.

Her mother was named Juda. The way my father met Juda was on the road to San Antonio. I was one year old at that time, lashed to the wagon seat so I would not tumble off. The wagon had a issue at Slide Off Pass with the wheel coming loose and the logs on the top sliding off the back like they are wont to do on that extreme incline. My father had to take me down and strap me to a tree so I would not toddle off. He was retrieving the spilled logs, and had about had all the good times he could stand, when along come a wagon driven by a man with a poorly looking woman beside him and a sturdy Negro woman in the back.

The man called out, Do you need some help with them logs.

My father, not being a man of much pride, I guess, said, I need some help with my whole life. And with that he commenced to weep like a baby – so he told me on the occasion that he recounted the story. He was not a delicate man nor a pessimist but he broke down and let her rip. I have not ever thought less of him for that particular moment. He had got hisself a sorry life, a bunch of logs going their own way, a broken down wagon, a hogback horse that given up, a chance of Indians coming along, and a terrible little baby boy strapped to a tree and making a racket.

The man in the wagon climbed down and helped him out. In the course of this, in some way a deal was struck that the man could take possession of the logs, which he was in need of as he was new to the place and expecting to build, and in exchange the Negro woman Juda would be borrowed to my father for a month to clean up his house, wash his laundry, and otherwise do the work of a wife minus the conjugal – there was to be none of that.

My father, being a man of his word, did not come near Juda during that time I don’t think. However, love was in the air, from his part, as I understand. I am not too sure what Juda thought of him. She must of liked him well enough, for when the time was up she did not return to them that owned her, and more deals was struck and finally after a while she and my father was together for good. You want me to be frank. I do not know of any wedding. I do not suppose there could of been one. But Samantha come along.

The only problem was, Juda was mean. She used to about do me in. I believe she might of hated me, but I am not sure. She was a hard worker, and determined, and kept the house in good order, but she could whip the daylight out of a bad little boy. Being as I was the only one of those around, I got more than my share of that.

I was a mere two years old at the time Samantha was born, but when I got my footing in life, and learned to say my piece and have a sense of what was going on about me, I recall taking my fists to Juda when she talked rough to the baby. We surely had our fights, and I would do nothing she said.

One particular time I recall, if not perfectly, it was a hot day and she kept me in the house, sweltering, and made me tend the cookfire, which I felt was women’s work, whilst I preferred to go out and help my father. I was about five years old and big enough to help him some.

Stir the pot, she told me.

She was hanging nappies at the hearth, and the whole place smelled bad, of nappies and sweat, and blazing hot, and I said, No, I ain’t going to stir it, I am going outside.

Stir it, said she.

I said, I won’t. You ain’t my boss. My daddy is my boss and you ain’t.

She boiled up with fierce anger in her head and her face. She was a sturdy woman. She had a fierce jaw, and skin that was pale for a Negro, and hair cut short to her scalp. She continued to tell me to stir the pot, and I continued to not do so, and the argument got loud, and I thought to make a break for the door, but she got me by the hair and dragged me back and said, I’ll snatch you bald.

Her hold on me, as I recall, hurt me quite a bit. She did not let go. I screeched like a caught varmint, and Samantha caterwauled in her crib, creating a further ruckus. When finally I broke loose of Juda I was fed up. I took up the poker out of the fire and thrashed it about and proclaimed in a pitch wail, I will leave my mark on you, I will! I do not like you, and I will leave my mark!

She ceased her hollering, ceased moving altogether, and the look in her eyes become murderous, and she said, in a slow voice, like she was talking to a slow witted person, You think I ain’t never faced down a hot poker before.

Then she undone her buttons and dropped her dress to the ground, and stood before me without a stitch on, and I seen a bunch of stripes on her body, darker than her skin.

Agape, I stood. God all mighty, Juda, who done that to you, I asked her.

His name ain’t important, said she. But I will tell you one thing. A poker ain’t going to get you your way. You stir the pot, you hear me.

I was inclined to stir it then, but my eyes was stuck on her, and my father come in and seen her stark naked, and he looked dismayed at the fearful sight, and rather doleful, and said, Juda, he don’t need to see that.

And she said, Yes, by God, he do.

After that, she put her clothes on, and I stirred the pot.

That was the most I ever seen of Juda, other than her meanness.

The fact that she was so hard on me and on Samantha makes it all the more curious the way she laid her life down, in such a bloody fashion, in defense of Samantha, the day a panther come calling.