Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

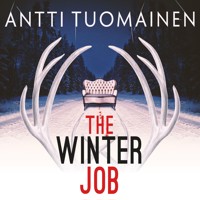

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

A desperate father's Christmas promise sparks a wild Finnish road trip involving an antique sofa, unexpected passengers and danger … A darkly humorous and warmly touching suspense novel about friendship, love and death, The Winter Job flies at 120 kilometres an hour straight into the darkest heart of a Finnish winter night. `Another wonderfully lean slice of European noir by one of its finest exponents. As darkly fun as any Coen brothers' offering´ Vaseem Khan `The king of the humorous crime caper´ Abir Mukherjee `With echoes of writers such as Christopher Brookmyre and Carl Hiassen, this is delicious stuff, expertly juggling dark humour and quirky characterisation against the backdrop of a frigid northern landscape´ Financial Times `A quirky, murderous road trip … Imagine blending a Donald Westlake comic mishap caper with some famous Nordic levity, and you might have something like The Winter Job´ Irish Times The NEW standalone darkly funny, poignant and uber-tense thriller from `The funniest writer in Europe´ (The Times) Fargo meets Carl Hiassen and Fredrik Backman … via the Coen Brothers ____ Sofas, secrets and a snowbound road to trouble… Helsinki, 1982. Recently divorced postal worker Ilmari Nieminen has promised his daughter a piano for Christmas, but with six days to go – and no money – he's desperate. A last-minute job offers a solution: transport a valuable antique sofa to Kilpisjärvi, the northernmost town in Finland. With the sofa secured in the back of his van, Ilmari stops at a gas station, and an old friend turns up, offering to fix his faulty wipers, on the condition that he tags along. Soon after, a persistent Saab 96 appears in the rearview mirror. And then a bright-yellow Lada. That's when Ilmari realises that he is transporting something truly special. And that's when Ilmari realises he might be in serious trouble… A darkly funny and unexpectedly moving thriller about friendship, love and death – The Winter Job tears through the frozen landscape of northern Finland in a beat-up van with bad steering, worse timing, and everything to lose… ____ `A madcap chase through a bleak winter landscape … damn hilarious and Tuomainen's dark humour is displayed at its best in what must surely be the best road movie of the year´ CrimeTime `This suspenseful tale of a desperate father's journey across the frozen landscape is filled with Tuomainen's trademark dark wit and unexpected thrills. Another winner´ Culturefly `It may seem hard to find good comic crime-writers, but clearly we haven't been looking in Finland´ Telegraph`Are you ready for the latest dose of dark humour, clever plotting, great characterisation and touching insights into the human soul? … A joy to read´ Nordic Lighthouse Praise for Antti Tuomainen `Humour drier than a desert snake's belly´ Ian Moore `You don't expect to laugh when you're reading about terrible crimes, but that's what you'll do when you pick up one of Tuomainen's decidedly quirky thrillers´ New York Times `Laconic, thrilling and warmly human´ Christopher Brookmyre `Right up there with the best´ Times Literary Supplement

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 326

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THANK YOU FOR DOWNLOADING THIS ORENDA BOOKS EBOOK!

Join our mailing list now, to get exclusive deals, special offers, subscriber-only content, recommended reads, updates on new releases, giveaways, and so much more!

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Thanks for reading!

TEAM ORENDA

ix

The Winter Job

ANTTI TUOMAINEN

Translated from the Finnish by David Hackston

Contents

HELSINKI, 1982

1

He wanted to see it one last time before he left.

Ilmari Nieminen looked at the piano, its shiny black exterior and ivory-white keys, like an almost endless row of bright, Hollywood teeth. The pedals looked clean, like freshly polished cutlery; its sides gleamed like ice in the moonlight.

His daughter’s piano.

In six days’ time.

As long as they could agree on one important thing.

Ilmari turned, looked around for an assistant and, as he did so, glanced outside.

Beyond the windows, underlined by the dark-green store logo, were the Christmas lights of Aleksanterinkatu, sparkling in gold and yellow. Large snowflakes, the size of wood shavings, slowly fell from the sky, gently rocking from side to side. The difference between the outdoor and indoor temperatures must have been around forty degrees. In the clammy warmth of the instrument store, one Christmas carol ended and another began, and before long the snow once more lay round about, deep and crisp and even.

‘Looking for a piano?’

Ilmari turned again and couldn’t tell where the exceptionally tall salesman in the polka-dot shirt had appeared from. He must have been lurking nearby, behind another piano, perhaps. Which seemed tricky, not least because of his height. Still, Ilmari didn’t want to think about the matter any further. He didn’t have time.

‘Yes, as a matter of fact,’ he replied, and pointed at the piano. ‘This one. I want to make sure this piano will still be here in six days’ time.’ 4

The salesman looked at the piano, then at Ilmari. He seemed hesitant.

‘That’s Christmas Eve,’ he said.

‘That’s why I’m asking,’ said Ilmari.

The salesman nodded, still hesitant. ‘A piano for Christmas, then,’ he said.

Ilmari confirmed this was precisely the case, and he was about to get to the main point but was cut short.

‘You’ll have to order the delivery today,’ said the salesman. ‘At the latest.’

‘That won’t be necessary,’ said Ilmari. ‘All I need is for this piano to be here on Christmas Eve. I’ll deliver it myself.’

The salesman said nothing. The tiny, plum-blue dots on his shirt seemed to shimmer against their black background. Ilmari tried not to look at the restless shirt and attempted instead to form an overall picture of the man. He was extremely tall and extremely thin. Ilmari couldn’t dispel the image of him folding and unfolding himself behind the pianos, waiting for a customer to appear.

‘So, if I’ve understood right,’ the salesman began, and Ilmari saw a cautious smile burgeoning on his long, patient face, ‘you’d like to buy the piano now and collect it on Christmas Eve. In that case, I’d be more than happy to sell it to you. An excellent choice, I must say; I have the same model at home. And this is the last one we have.’

His last sentence didn’t sound like a sales pitch. In fact, nothing he said sounded like a sales pitch.

‘The last one?’ Ilmari asked.

‘We won’t be getting any more this year,’ he replied, sounding as though he was genuinely upset and not merely trying to push the sale. ‘This is the only one.’

They both looked at the piano and, probably because of this new information, something in Ilmari now saw it for the first time.

Though, of course this wasn’t the first time. 5

The first time had been almost two months ago, when Helena, his twelve-year-old daughter, had brought him into the store and shown him what she wanted for Christmas; now that she had started piano lessons with a renowned teacher and had made such swift progress, she’d decided she wanted to become a concert pianist. She had sat down at this piano and started playing, and Ilmari had known he couldn’t tell her about his money problems, or about the fact that since the divorce, with Helena and her mother keeping the apartment, the lion’s share of Ilmari’s wage from the postal sorting office was spent on the mortgage, child-support payments and his own rent, and that right now the only things in his wallet were his driving licence and his yearly ticket to the Film Archive. Ilmari hadn’t breathed a word about any of this. Instead, he had tried to hide how moved he was to see Helena’s fingers dancing across the keys and, above all, to listen to what her fingers and the keys produced together. And as Helena had finished playing and stood next to the piano, that’s when Ilmari had made his decision.

He had promised her that piano, and he’d promised it for Christmas.

And now, six days before Christmas Eve, he was standing on the first floor of that same music store with a nervous salesman a full head taller than him, trying to find a solution to a problem that had taken on new dimensions. At the same time, still looking at the salesman’s rapidly blinking eyes, he started to sense something else too. He found himself thinking that he and the salesman might have something in common after all.

‘I don’t remember you from last time,’ said Ilmari.

‘Pardon me?’

‘I visited the store two months ago.’

‘I didn’t work here then,’ the man said with a shake of the head. ‘In fact, I only started five days ago.’ 6

Ilmari waited, sensing that the salesman wasn’t finished.

‘I’m a composer,’ he said eventually. ‘But composing doesn’t … And, seeing as I know these instruments quite well, I thought … Work and pleasure, you know … But this job is mostly commission-based, and I … as I said, I’m a composer, and I suppose I don’t really…’

‘I understand,’ said Ilmari. ‘I’m in a similar situation myself.’

‘You’re a composer too?’

‘I’m a postman,’ he said. ‘And I’m buying a piano. But I won’t have the money until Christmas Eve, and I’d like to reserve this piano now. Especially as it’s the last one.’

The salesman looked at Ilmari, and Ilmari thought he now appeared even more pained than before.

‘But, without the money, without any downpayment, I don’t think I can … I’m not sure my boss will allow…’

‘I suggest a slightly unusual arrangement,’ Ilmari began. ‘I will reserve the piano now, and when I collect it on Christmas Eve, I will pay the full manufacturer’s suggested retail price, meaning you will get the maximum commission. On top of this, I’ll pay, let’s say, ten percent extra as a reservation and storage fee – or whatever you want to call it. You can enter it in the books however you please.’

The salesman swallowed. Ilmari could see that the composer knew how to count.

‘That would save Christmas,’ said the composer.

‘That would save Christmas,’ Ilmari agreed.

The composer looked first at the piano, then at Ilmari.

‘If I reserve this piano for you, how do I know that you really will come back on Christmas Eve?’

‘Because I’ve given you my word,’ said Ilmari. ‘Because this is my daughter’s piano.’

2

Ilmari walked through the blizzard to Kamppi, found the right bus stop, waited fifteen minutes in the freezing cold, then climbed on board the number thirty-nine bus, dipped his ten-ticket travel card – now a little softened from sitting in his pocket – into the machine and allowed it to punch the final hole in the corner. He took a seat by the window near the back of the bus and felt warm air from the heater blowing against his left shin. The bus filled up one stop at a time and started to smell of damp clothes, as the snow melted on people’s jackets, shoes and woolly hats. He got off the bus in Pitäjänmäki. The snow had gathered in trenches along the pavements of this industrial neighbourhood, so Ilmari had to fight his way through it. According to the map that he had torn out of the telephone directory, his destination was around one kilometre from the bus stop.

Ilmari trudged through the snow, thinking to himself.

When the offer had presented itself, he had leapt at it. Despite the fact that he didn’t even know the guy. He’d got the tip-off and the phone number from Riekkonen, one of his older colleagues at the sorting office. At the end of the day, he was very low on options. He couldn’t ask his parents for money for the simple reason that they never had any, except to spend on cigarettes and alcohol; they were barely able to look after themselves. And as for friends from his youth and early adulthood, they had all practically disappeared after starting families of their own. And in any case, it was unlikely they would have been able to lend an old school mate enough money to buy a piano. All in all, this job offer and the payment he would get 8would solve his problem. And this was why he had decided to take four days’ unpaid leave from his proper job at the post office, and why, as evening drew in, he now found himself walking towards an industrial area in northern Helsinki, only days before Christmas, his final destination: Kilpisjärvi – right at the other end of the country.

He passed various warehouses and factory buildings, most of which were unlit. It was as though the streetlamps were positioned further apart than they were downtown; the dark blind spots between the lights appeared to be getting longer. Ilmari tugged his mittens up his wrists, as the wind seemed to be targeting them with particular accuracy. Snowflakes tingled on his face, where they melted and dripped down inside his collar.

Finest Antiques & Furniture, read a faint blue-and-white neon sign, its lower edge slightly hanging off the wall. He had arrived. At first, Ilmari thought this was yet another unilluminated, two-storey, roughcast construction, until he noticed a light at the other end of the building. He walked to the window, and through the Venetian blinds he saw slices of a poster of Victoria Principal and a cluttered desk on which sat several calculators. He located the bell in the doorway, and before its sound had faded, the door opened, and the frozen air was mixed with a curious blend of aftershave and onion. Ilmari had barely introduced himself and explained why he was here when the man showed him inside.

‘Pentti Leinonen,’ said the man. ‘The finest antiques.’

Ilmari brushed the snow from his jacket and scarf, pulled the hat from his head and followed Leinonen further into the building. They went through another door into the furniture showroom. Leinonen switched on the lights, and Ilmari looked around. He saw an array of items, mostly furniture of various ages, though none of it was exactly antique, let alone of the finest 9quality. Some of the items were nothing more than junk: heaps of lamps, piles of rugs, stacks of paintings. He looked at the middle-aged man next to him, who smelt of Tabac and meat pasty, and only now did he notice that the man’s right eye was made of glass and stared in a slightly different direction to his left.

‘Need any furniture?’ Leinonen asked.

‘No, thank you,’ Ilmari replied.

For a moment, they stood in silence. Leinonen wasn’t the person Ilmari had spoken with on the phone, and he felt a level of relief at the thought.

‘The prices are all tax-free,’ said Leinonen.

‘I came to pick up the car,’ said Ilmari.

They stood on the spot a moment longer, then Leinonen walked off, and Ilmari followed him once again, which was obligatory as corridors the width of woodland pathways were the only routes through the clusters of junk. But what set this place apart from the woods was its smell: the odour of mould was thick and sour. Leinonen stopped, and Ilmari saw that they had reached the gable facing the road, where there was a roll-up door. And in front of the roll-up door was a van. If you could call it that.

‘I understood from our phone call,’ Ilmari began, ‘that you’d been asked to find a second-hand Fiat Ducato, or something similar.’

‘After expenses and deductions,’ said Leinonen, ‘and given the timeframe, completely out of the question. This one would have been out of the question too, if I hadn’t chipped in a bit of my own.’

Now Ilmari realised what it was about Leinonen that disturbed him. It wasn’t the combined aroma of meat and rice and perfume committing a full-frontal assault on Ilmari’s senses, 10or Leinonen’s eyes, with which it was impossible to make any kind of contact. It was the way he seemed to approach everything: he might not have been entirely dishonest, but this was the kind of guy you wouldn’t want to buy a second-hand car from. During their short acquaintance, Leinonen had told him he offered the finest antiques while surrounded by piles of junk, suggested a spot of tax avoidance, and now it seemed he was hiding some of the money used to acquire the van. In one instance, however, Leinonen had told the truth, and in that he was perhaps more correct than he knew.

There was no time for anything else.

The light-blue van was a Thames, a British vehicle. Ilmari wasn’t an expert, but he was relatively certain this particular model had been discontinued some time ago.

‘I put on some winter tyres for you,’ said Leinonen.

Ilmari walked around the van, checked the undercarriage and the tyres, and saw that the latter were newish, but that there was one type on one side of the van and a different type on the other, which meant they were more than likely stolen and, what’s more, from two different vehicles. Ilmari arrived at the back door, opened it and concluded that, in this respect, everything was as it should be.

That said, seeing the sofa in the back of the van was like stumbling upon the Koh-I-Noor diamond in a sweaty changing room.

Unlike everything else Ilmari had seen in this cluttered warehouse, the generous sofa squished into the back of the van really was the finest of antiques. The dark-red upholstery was opulent, the dark-brown wooden fixtures gleamed. Ilmari could easily understand how this skilfully restored sofa might be important to someone, and not only in terms of its monetary value, though naturally that must play a part. He looked at the 11sofa a moment longer, checked the fastenings and tightened the straps on both sides, and closed the door. Then he walked round to the driver’s side and opened the door. The keys were in the lock, the tape player looked new and everything else looked old. The driver’s seat looked as though a very heavy driver had been sitting in it for several decades. Which, of course, was entirely possible.

‘As you can see, this vehicle is specifically for long-haul journeys,’ said Leinonen. ‘I took that into account – when I heard you weren’t taking the most direct route.’

‘I’m going to stop in Ilomantsi on the way,’ said Ilmari, more to himself than to Leinonen. ‘Then Vaasa.’

‘I know a lot of people in both towns,’ said Leinonen. ‘Smashing places.’

Ilmari thought it all but certain that Leinonen had never visited either town. Without continuing the conversation, he walked around the vehicle one more time, opened the passenger door and checked the dashboard on that side. He inspected the old van’s interior for a while then took a deep breath. Very well, he thought. He would drive the van and the sofa all the way north to Kilpisjärvi, so he could buy his daughter a piano for Christmas. Everything else was of secondary importance. What did it matter if he froze, how uncomfortable the seat was or how difficult it was to drive an old English van in the harsh Finnish winter?

‘Did you bring the money?’ asked Leinonen once Ilmari had closed the door.

Ilmari walked up to him. ‘What money?’

‘Seeing as you’re renting the car,’ Leinonen added, both his eyes now avoiding direct contact.

Ilmari had only known Leinonen a matter of minutes, but he could already say that he was a man who would never stop trying 12his luck. The mere whiff of cash would make him try and pull a fast one.

‘That isn’t the arrangement, and you know it,’ said Ilmari. ‘You’re supposed to give me money – for the petrol.’

He said nothing further. He stood in front of Leinonen long enough that beads of sweat began pushing their way out of Leinonen’s forehead as he clenched his thumbs in his fists. Eventually, Ilmari managed to make contact with Leinonen’s working eye. He heard Leinonen swallow.

‘I remembered wrong,’ said Leinonen. ‘When you do a lot of business, you forget the details.’

From his back pocket, he took a glossy brown envelope. Ilmari took it, opened it and counted the money. The sum was just enough to cover the petrol, but nothing else. Ilmari slid the envelope into his jacket pocket.

‘Will you open the door?’ he asked Leinonen and sat in the car.

‘The map’s in the glove compartment,’ Leinonen called as he strode towards the roll-up door and flicked a switch.

The door rose with a squeal. The snowflakes floating outside sensed it was opening and rushed in. Once the door was fully open, Ilmari started the engine and managed to put the van in gear on the second attempt. Then he carefully steered the English classic out into the frozen weather and towards the gate and the street beyond it, and, without looking back, headed east to Ilomantsi.

At least, this was his intention.

As he accelerated out of the junction and onto the Ring Road around the city, he noticed he was driving without functioning windscreen wipers. Normally, or in any normal vehicle, this wouldn’t necessarily be a problem: you don’t usually need windscreen wipers in the dead of winter. But the Thames wasn’t 13a normal vehicle in this sense, or in any sense. The way in which the barrel-shaped heater in the footwell pumped hot air into the cab meant that the almost vertical windscreen above it heated up and seemed to attract the billowing snowflakes like a magnet before only partially melting them. Before he’d even reached the next junction, Ilmari knew he had a problem.

As he drove, he wound down the side window, leant forwards, reached a hand out of the cab and wiped the windscreen from the outside with his mitten. Just then, he saw the lights of a Teboil petrol station up ahead. He took the slip road off the dual carriageway, pulled into the forecourt of the petrol station and parked in a row of vehicles outside the repair garage. He sat in the cab for a moment and thought through his options, before quickly concluding that he had very few. He hoped he was wrong. He pulled on his woolly hat, stepped out of the van, locked the door, walked to the garage and learnt that he had been right after all.

There were no spare parts for the Thames, and the next time anyone could have at least assessed the situation would be late afternoon the following day.

The assistant, with a head of bright, peroxide-startled hair, nonetheless tried to be as friendly as she could, clearly wanting to show empathy in the face of Ilmari’s misfortune. The garage smelt of oil and grease, and from the loudspeakers in the cafeteria Ilmari heard how many partridges had once sat in a pear tree.

‘Where are you heading?’ the woman asked.

‘Up north,’ said Ilmari, then added, ‘eventually.’

‘Dear, oh dear,’ she said. ‘Then we need to get those blades working. You’d need to be Ari Vatanen just to keep that thing on the road.’

Ilmari thought even the newly crowned rally world champion himself would think twice before driving the Thames – assuming 14the Thames ever got back on the road. Ilmari couldn’t think of anything else to say – maybe there wasn’t anything to say – so he thanked the woman for her help and turned towards the door.

‘I hope you get the wipers working again,’ she called after him. ‘It’s going to be murder up north.’

Her last sentence rang in Ilmari’s ears. It was more a curse than a weather forecast, and felt ominous, not least because he was missing both parts and a mechanic.

He walked across the brightly lit forecourt towards the van, avoiding the slippery furrows smoothed by hundreds of tyres, and trying to think which service station he could stop at next, because there was only one thing that mattered: he had to get going.

Lost in thought as he stepped across another patch of ice, he heard a voice behind him.

‘My old man used to have a Thames,’ someone said. ‘Ask inside for a set of pliers and a Phillips screwdriver, and I’ll fix your wipers.’

3

Pitäjänmäki was like a massive fanny: dark, slippery and a mystery to mankind. Otto Puolanka gripped the steering wheel and drove past the building twice before realising it was the one he was looking for. Finest Antiques & Furniture. He steered the car through the gate and pulled up by the wall, switched off the engine of his old Saab 96, stumped his Camel into the already full ashtray, managing to spill ash on the passenger seat, then stuck his right hand into the footwell at the back and groped around for his drink. Eventually, he located the half-full bottle of cheap vodka and unscrewed the lid. As he raised the bottle to his lips, he saw tyre tracks in the snow. If he hadn’t been used to drinking straight from the bottle, he would have spat the liquor into his lap. He was already furious, but now he could feel waves of anger heaving within him, a storm rising.

The tracks started from the roll-up door, curved towards the gate, mixed with other tracks, then disappeared altogether.

This meant he was late.

Otto didn’t know why, every time he popped into the bar to perk himself up, he ended up staying longer than he’d planned. He had simply intended to rinse the stale taste of vodka from his mouth with some cool, crisp lager, and he’d calculated that he had plenty of time to do this – but before he knew it, he’d ended up playing darts and having not one but three pints.

He screwed the lid back in place. He needed a refill.

He opened the door and stepped out into the cold. The wind was stronger now, the snow attacked his eyes and ears. Otto took a pack of Camels from his right pocket, lit a fresh cigarette and 16trudged through the snow to the door, mentally cursing all the way. His knee-length leather jacket kept out the wind, but because he didn’t have any gloves, his fingers felt the chill. He rang the buzzer, exhaling smoke into the winter’s evening.

The door opened, and Otto stepped inside.

‘Pentti Leinonen,’ said the pungent-smelling man who opened the door. ‘The finest antiques.’

Otto said nothing. He took the man by the arm, gripped him tightly and walked him into the furniture warehouse. Once inside, Otto released his grip and took the cigarette from his lips with a cupped hand.

‘No smoking in here,’ said the man who had introduced himself as Leinonen. ‘You wouldn’t do that in Sotheby’s.’

‘Where’s the sofa?’ asked Otto.

‘What sofa?’

Otto wanted to look the man in the eyes, but he couldn’t find them. Well, of course he knew that the eyes are generally located in a person’s head, approximately in the middle, but for some reason making contact with these particular eyes seemed all but impossible. Otto defiantly filled his lungs with smoke again, then exhaled and looked around. He felt drunk, but more than that, he was furious. It was often hard to tell the two apart.

‘You know what sofa,’ he said. ‘And another thing. I saw tyre tracks in the snow. What kind of car is it?’

‘What’s this all about?’ asked Leinonen. ‘We only sell antiques of the highest quality—’

‘This is a low-life hiding place for stolen goods,’ Otto retorted. ‘So I’ll ask you again: where is the sofa and what make is the car?’

Leinonen’s tongue ran across his lips, as though greasing them for use. Then he stood up straighter – or tried to, at least.

‘How much?’ he said. ‘If I might ask, between friends. How much are you willing to pay for that kind of information?’

17‘Between friends?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Pay?’

‘Yeah…’ Leinonen hesitated. He looked confused.

Otto dropped his cigarette on the floor but did not stamp it out. Leinonen again ran his tongue across his lips, but this time he didn’t say anything.

‘Don’t friends usually help one another?’ asked Otto. ‘For free? Without payment? You really want us to be friends?’

‘You what?’

‘Would you answer my personal ad?’ asked Otto. ‘“Looking for a friend. Photo replies only.”’

‘What?’

‘“I’m into music,”’ Otto continued. ‘“You don’t have to dig the same music as me, as long as you’re a nice guy.”’

‘What?’

Otto clenched his fists, opened and closed them. His joints cracked.

‘“PS,”’ he continued. ‘“Layabouts, don’t bother.”’

‘You’re crazy,’ said Leinonen.

Otto took a deep breath. Sooner or later, everybody said the same thing. You couldn’t trust people; he’d learnt that. That’s why he didn’t have friends, and that’s why he couldn’t find friends. And why had he dropped his cigarette on the floor? He needed a cigarette. He shoved his hand into his left pocket – and yelled. The pain was dizzying, excruciating. He pulled his hand out of his pocket, looked at where he’d stuck his finger, what had jammed its way under the nail of his forefinger.

The darts.

He understood what had happened. The vodka. The thirst. The bar. The lager. The darts. Which had ended up in his pocket.

A second later, he realised something else too.

18The man calling himself Leinonen was trying to run past him.

Otto quickly raised his hand. His sole intention was to stop him, but the man’s surprisingly powerful lunge, the strength of Otto’s flick of the hand, and the pack of darts he was gripping in his fist combined forces, and all five darts sank into the man’s cheek like needles into a pin cushion.

Leinonen stopped, looking both as though he had realised something important and run headlong into a wall. Otto was still holding on to the darts. He released his grip and stared at the man in front of him, who now had a full set of red-flighted darts in his right cheek and was shifting his weight from one leg to the other, his hands flailing through the air.

‘Ay em ou,’ the man called Leinonen said – or shouted, more like.

At first, Otto didn’t understand what the man was saying, but then he thought he knew. ‘Take them out,’ he was saying, over and over again. Otto walked up to the man, gripped the darts with one hand and the man’s head with the other, then ripped the darts out of his cheek. Blood sprayed like a tin of paint punctured with a fork. The man called Leinonen slapped himself on the cheek, held his hand there and looked like he was finally ready to talk.

‘The sofa’s in a van on its way to Ilomantsi, then Vaasa, and finally to Kilpisjärvi,’ he said eventually. ‘It’s an old, light-blue Thames, a British van. A quality motor.’

For a moment, Otto considered what he had just heard. He looked at the man with blood dripping between his fingers and onto the floor and bubbling at the corner of his mouth.

‘I’d expected something newer,’ said Otto. ‘A Fiat Ducato or something similar.’

Now, on top of everything else, the man called Leinonen was getting agitated.

19‘Everybody’s complaining about that bloody van,’ he said. ‘It was the best I could get in the timeframe—’

‘By everybody,’ Otto began, ‘I suppose you mean the driver? What does he look like?’

‘What does he … look like?’

Otto was starting to run out of what patience he had left.

The man appeared to sense this. ‘Shorter than you,’ he said quickly. ‘Slimmer than you, long, dark hair, a bit of a rocker, brown eyes, a high collar on his jacket … That’s all I can remember. But despite his build, somehow … threatening or … determined or…’

‘Threatening?’ said Otto. ‘Or determined?’

‘Well,’ the man called Leinonen began. ‘He knows what he wants. And he won’t stop until he gets it. That’s the impression I got. He’s somehow … uncontrollable … unstoppable even.’

Otto spat on the floor, as though he had again tasted something rancid that didn’t belong in his mouth. The man called Leinonen looked at him.

‘Believe you me, nobody’s unstoppable,’ said Otto. ‘When did he leave?’

The man looked to the side. Otto followed his eyes and was taken aback. The grandfather clock showed the right time.

‘Half an hour ago,’ said Leinonen.

If the man and the sofa were on their way to Ilomantsi, they would head east out of the city and drive towards Porvoo, then turn onto Highway 6 before Loviisa. If Otto squeezed everything he could out of the Saab, he might catch up with the old van before Kouvola and would be back in Helsinki by morning. He had been hired to deliver the sofa to a client – it didn’t matter to him who it was – and that is what he intended to do. That was how he operated, and his reputation depended on it. He got the job done. Any job. If it was a sofa the client wanted, a sofa the 20client would have. And the morning after that, he would be in the Canary Islands, in Las Palmas, where a familiar bar and waitress would be waiting for him…

‘What about my commission?’ asked Leinonen, snapping Otto out of his reverie. ‘For the information and the damage?’

He turned his head, showed Otto the holes in his bloody cheek. The grandfather clock struck the hour. The sound was dull and stuffy.

‘I’ll have to tie you up,’ said Otto.

‘What?’ said Leinonen.

‘Just for a few days,’ Otto nodded and looked around.

His attention was drawn to the specially lit Christmas section of the warehouse – Is there anything there I can use to tie him up? – and didn’t see the man called Leinonen hurtling towards him before it was too late. As he leapt forwards, Leinonen hurled a heavy metal bowl, and Otto heard the same kind of clang inside his head as he had from the grandfather clock. He lost his balance and fell on his back. Leinonen was battering him with the metal bowl now, pounding his face. Fine, thought Otto; he had suggested a neutral solution to the situation, he had tried to be friendly, he had offered friendship, but this man had rejected him. With his left hand, Otto managed to grip the set of sparkling Christmas lights hanging overhead. With the metal bowl still beating against his forehead, he sat up, thrust his right hand between his attacker’s legs and clenched. Leinonen shouted and lowered the metal bowl but didn’t drop it altogether. Otto staggered to his feet, pressed himself against Leinonen and quickly slung the Christmas lights around his neck, first once, then twice. Otto tightened his grip on the lights until the metal bowl clattered to the floor and Otto’s arms were numb and all he could hear was the sound of his own panting. Then he pushed Leinonen into a dark-green armchair, took a deep breath, and as 21Leinonen sat slumped in the old recliner – his cheeks glowing gnome-red, the Christmas lights flickering around his neck, his eyes staring at the ceiling – Otto thought he looked like someone whose passion for Christmas was so great, it had become his downfall. Otto touched first his nose, then his forehead. The bleeding wasn’t very heavy, but he was bleeding all the same. But a little rough and tumble didn’t annoy him as much as what had happened. Wasn’t he already late? Why had this man had to stall him so long? He spotted a sack nearby, among the clutter of objects in the Christmas section of the warehouse. He picked it up and opened it. It was full of carefully wrapped presents. He wiped his nose and forehead, his sweaty neck, and looked at the grandfather clock that had just chimed. Maybe the situation wasn’t completely hopeless after all, he thought.

He would catch up with the driver and the sofa before they reached Kouvola.

But one thing was certain: from now on, he would not be nearly as friendly.

4

On a dark winter’s evening, the service station looked like a bright planet against the black canvas of outer space. And the figure that Ilmari Nieminen had heard, then seen a few metres to his right was, in some way, like a creature from outer space. Ilmari realised that this impression was partly due to the large sports bag in the man’s hand, which appeared so heavy that he was doubled over with its weight.

Ilmari flinched, felt a flicker inside him. There was something familiar about this man, and, as unlikely as it seemed, Ilmari concluded that he must know him.

‘Just because your father had a Thames,’ he began, ‘it doesn’t necessarily mean you know how to mend one.’

‘Back inside, I heard you were heading north,’ the man continued as if he hadn’t heard Ilmari’s question. ‘So am I. If I fix your van, you can give me a lift.’

‘I’m not taking the most direct route,’ said Ilmari.

‘I’m not in a hurry,’ the figure replied, and now Ilmari finally recognised the tone of voice, the manner of speech.

The bright lights of the service station glowed behind the figure, but little by little Ilmari began to make out the details. As he had suspected, the figure was around his age – about thirty-five, give or take – he had sharp, piercing eyes, slender but soft features and blond hair, short, tangled and partially standing on end. He was wearing a light-brown suede jacket with a thick lining, black baggy trousers and large, white basketball trainers that seemed unsuitable for the time of year. Ilmari could well have imagined that he was looking at Sting, who for one reason 23or another had found himself at a service station in northern Helsinki and could suddenly speak fluent Finnish. But Ilmari didn’t imagine this. Now he knew whom he was looking at with absolute certainty.

‘Antero Kuikka,’ he said.

Filled with the noise of the traffic, the pause lasted perhaps two seconds, then the figure nodded.

‘Ilmari Nieminen.’

They both took a step forwards, reaching out their hands. Ilmari calculated that it had been almost exactly twenty-three years since they had last shaken hands. At the same moment, Ilmari remembered other things. Good things at first, but straight afterwards a bad thing. Still, he didn’t want to dwell on the events of their boyhood any further and returned to what they were doing and why. There wasn’t any time to lose.

‘A Phillips screwdriver and a set of pliers?’ Ilmari asked.

‘Ask for a pair of cutters too, just to be on the safe side.’

‘Why don’t you ask them yourself?’

‘The same assistant has already thrown me out twice today, for not buying anything after my morning coffee. I can’t afford a second cup. I doubt he’s going to change his mind and suddenly start lending me their tools. I’m an unwelcome guest. And not just here.’

There was something exceptional about the way Antero Kuikka expressed these things, but something familiar too. He didn’t beat around the bush, let alone try to hide things. He simply stated the truth. And this is exactly what he had done twenty-three years ago too.

Ilmari made his decision.

He walked back into the garage, explained the situation, left one of the banknotes he’d got from Leinonen on the counter as a deposit, borrowed the tools and returned to the van. He 24opened the passenger door, and Antero swung himself onto the floor of the cab in a single, smooth movement that looked like a combination of practice and natural agility. Then Antero asked Ilmari to hand him the tools, like a surgeon at an operating table.

Around ten minutes later, Antero slid out from the cab with the same easy, gymnastic movement and asked Ilmari to try the engine. Ilmari walked round the Thames, sat down and turned the key in the ignition. The van started, and Ilmari switched on the windscreen wipers.

They worked.

‘A lift up north would be nice,’ Ilmari heard beside him. ‘Like I said, I’m in no hurry.’

Ilmari returned the tools to the garage, got his money back and walked back to the van, where he found Antero Kuikka rummaging in his large sports bag. The bag was on the snow-covered ground in front of the back door, and inside the bag Ilmari saw not only clothes but a surprising collection of cassettes. There might have been more cassettes than clothes. Ilmari couldn’t quite work out what this said about his old childhood friend and travelling companion to be.

‘It’s a long journey,’ said Antero. ‘We’re going to need some music. Any requests?’

Ilmari was about to say it didn’t matter; all that mattered was that they got going. Then he thought of the length of the journey and remembered what it had felt like to drive to Kuopio, trapped in a car for hours, to the soundtrack of Kake Randelin’s greatest hits.