Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

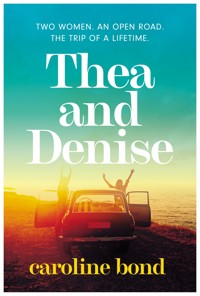

'Oh, you're not crazy, Denise. I think this is probably the sanest you've ever been...' Two women. An open road. The trip of a lifetime. Thea is confident, sorted, determined to have fun, but there are sorrows beneath the surface of her life. Denise is struggling under the weight of her many commitments and in desperate need of some excitement. When these polar opposites meet, and unexpectedly become friends, they realise they're both looking to escape. So begins a road trip that leads them far from home and yet closer to their true selves. But they can't outrun their pasts forever and when things start to become complicated, both women have an important decision to make. Do they give up or keep going? Turn around or drive on?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 422

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Caroline Bond

The Forgotten Sister

The Second Child

One Split Second

The Legacy

Published in hardback in Great Britain in 2022 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Caroline Bond, 2022

The moral right of Caroline Bond to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 83895 404 8

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 405 5

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 406 2

Design benstudios.co.uk

Printed in Great Britain

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

To my friends.

Prologue

THE SKY was filled with purple-tinted clouds.

The sun was coming up.

The roof was down.

The roads were clear.

Thea drove fast, following the smooth contours of the coast road with ease. Denise tilted her head back and felt the warmth of the new day hit her face.

They were mistresses of their universe.

As the sun rose higher, the road started to narrow and climb. After a few miles, Thea turned off. A plume of dust rose in their wake as they rolled and bumped along the unmarked track. Denise had no idea where they were. They drove on, away from or towards something – she no longer cared.

After another ten minutes or so Thea swung the car around a bend and brought it to a stop.

They’d reached the end of the road.

In front of them was a stretch of scrubby grass, the sky and the cliff edge. Away to the left, on the headland, sat a lighthouse, a curiously squat affair topped with a black-capped dome. Beyond it the coast unfurled in a seemingly never-ending series of rocky inlets. Denise heard the sea heaving and crashing somewhere far below. Above them the gulls wheeled and screamed.

‘Where the hell are we?’

‘St Abb’s Head.’ The wind whipped Thea’s hair across her face. ‘Isn’t it beautiful?’

‘It is.’

They sat, side-by-side, taking in the view. The grandeur of it silenced them both. They’d been travelling together for barely a week, but in that moment Denise felt closer to Thea than she had to anyone else in her entire life. She wanted Thea to know that. ‘You’re a good friend.’

Thea smiled. ‘You too.’

Denise breathed in the fresh, sharp air. She caught sight of her reflection in Thea’s sunglasses: her hair a mess, not a scrap of make-up on her face, her nose and cheeks tinged red with sunburn. She looked good. Even more importantly, she felt good – the best she’d felt in a very long time. So much had changed since they’d left home, not least Denise herself. She was a different person, happier, freer, braver, and that was due, in large part, to the woman sitting next to her.

They fell silent again, reflecting on what they’d learnt about themselves, and each other, over the past few hectic, revelatory days.

Indifferent to the presence of such wise women in their midst, the gulls rose and fell at the cliff edge. Their screaming and flapping reminded Denise of the problems mounting and massing at their backs. Real life was going to catch up with them eventually. They couldn’t keep running for ever.

Although up on that wild, isolated promontory, with the sun shining down on them and the wind blowing in off the sea, it felt like perhaps they could.

‘So,’ Denise finally asked, ‘what do you want to do now?’

Thea looked at the limitless sky stretching out beyond the cliff edge and said, ‘Keep going.’

PART ONE

Chapter 1

SHE WOKE up on fire.

Desperate to get some air onto her molten skin, she began kicking at the bedcovers. Her nightie clung to her like a sick child. It fought back as she attempted to drag it off, entangling itself with her arms and sticking to her face. She panicked. Her heart thudded and her breath caught in her throat. For a split second she wondered if this was what waterboarding felt like, but immediately discounted the thought as hysterical. Free at last, she threw her nightie on the floor. She reached for the glass of water on her bedside table and glugged down as much as she could manage, trying to put out the flames. The sensation of the cold water trickling down the insides of her stomach was unpleasant. Stripped and doused, she leant back, closed her eyes and waited for the inferno to die down.

It did so quickly, the heat radiating off her in waves. The slick of sweat that had coated her body only minutes earlier evaporated, leaving behind a deep chill and a tightness that felt like black pepper under her skin. She reached for the duvet and pulled it up around her. As the shaking subsided and her body slowly unclenched, something close to normal bodily function finally returned.

Released from the grip of her night sweat, Denise regrouped and began her second battle of the night – hand-to-hand combat with her brain.

Tonight the battalion of worries was fronted by a number of seemingly intractable work issues, but soon other concerns joined the assault, chief amongst them her sons. There was Aaron’s stormy relationship with his girlfriend, Millie – they seemed to do nothing but fight, make up, then start all over again, often over the course of a single day. There was Lewis’s future – if his A-level results were as bad as she was expecting, God knew what he was going to do. He couldn’t play golf for the rest of his life. Next her mind pivoted to her youngest, Joe, and his persistent acne, and the impact it was having on his confidence. The weight of worry never seemed to get any lighter. Indeed, as her sons headed into adulthood, she found herself increasingly at a loss as to how to help, what to do or say to make it better. A hug and a kiss no longer cut it. Then there was Eric, her ageing father-in-law, who consumed so much of her time and offered so little in return, other than bad temper and military statistics. And down there, right at the bottom of a list that she should surely be near the top of, was her eighty-three-year-old mother, Lilian, hundreds of miles away in the North-East, alone in her little cottage by the sea. How long was it since Denise had spoken to her mum properly, without having her eye on her emails or her attention directed elsewhere? How long since she’d been to see her? Months!

Having exhausted her stock of family anxieties, Denise’s brain fought wearily on, skirmishing with a myriad of smaller guilts and concerns. Before she knew it, she was worrying about the cracked drawer in the freezer, and whether she’d texted the joiner with the right measurements for the shelves they were having fitted in the dining room.

Enough! She knew worry was wasted energy.

She scrunched up her toes and released them ten times. She focused on each vertebra in her spine, imagining them aligned in a smooth curve. She tried to breathe from her diaphragm, resting her hand on her belly to check she was doing it correctly. She visualised being by the sea, imagined the soothing sound of the waves, the fresh air, the sense of peace she always felt when she was close to water. She rolled over onto her front and tried to channel her inner child. She rolled onto her side and counted her blessings.

Nothing worked.

She threw in the towel at 1.16 a.m. She simply couldn’t face lying there any longer, staring into the darkness, listening to her husband, Simon, sleep, peacefully unaware of her nocturnal battles.

Trying to get to sleep was such a contradiction. Sleep was not responsive to effort. Once you started trying, you were doomed, as she knew from bitter experience. She slid out of bed, mindful of not disturbing Simon. He had a meeting down in Southampton in the morning. The alarm was set for 5.45 a.m. Four and a half hours. Not long if you had an early start; an eternity if you were awake and fretting. She shrugged on her old towelling dressing gown, crossed the landing quietly and crept downstairs.

A darkened house, with everyone else dead to the world, was one of the loneliest places on the planet. Denise chided herself for the thought. Of course that wasn’t true. A teenager sleeping rough on the streets, a prisoner in a locked cell, a security guard patrolling an empty office block, an arthritic old lady sitting up in her chair, alone with her fading memories – the list of lonelier places and circumstances was endless, and deeply depressing. She really needed to limit her news intake before bed.

She switched on the under-cupboard lights in the kitchen, feeling reassured by their warm glow. As she waited for the kettle to boil, she moved the plate and knife from someone’s evening snack to the sink, swept the crumbs off the worktop into her hand, threw them away and returned the loaf to the bread bin, twisting the bag shut as she did so. Then, despite having made a pact with herself that she wouldn’t, she looked at her phone. There was, as always, a tranche of new emails. The downside of dealing internationally was that someone, somewhere, was always awake, working and awaiting a response. She skim-read through her messages, mentally prioritising them. That done, she composed a polite, but firm email to the supplier in San Francisco, reiterating her take on the latest supply issues and stressing the importance of it all being sorted before the next shipment.

Having corralled some of her ‘work monkeys’ into order ready for the morning, she felt a little better. She slipped her phone back into the pocket of her dressing gown and made herself a mug of tea. Proper tea, not camomile for Denise – it was bad enough being awake in the middle of the night, without drinking hot bath water. These small acts of distraction helped. The relentless, flickering spool of things to be done or sorted that played almost constantly inside her head slowed, their projection dimmed.

Denise knew she was lucky.

She had a close family: a faithful husband, three strapping sons and a mother who, although old, was fit and independent. She lived in a nice home and had a good job that, although busy and demanding, fitted around her family responsibilities. She had safety, security and more than enough money to keep the wolf from the door. Indeed, she – or, rather, they as a family – had the financial resources to track any wolf that might be found lurking in the manicured gardens of St Albans, humanely capture it and ship it off to Alaska, to be released back into the wild with its brethren. She was essentially a well-off, moderately healthy middle-aged woman. She had absolutely nothing to complain about. Nothing substantial going on in her life to explain her current sense of frustration, dissatisfaction and all-round off-kilterness.

Cradling her drink, Denise wandered through to the lounge. It was cast in silvery-grey moonlight, which made it look like an old black-and-white film set, although she was hardly rocking a Joan Crawford housecoat and chignon. She was wide awake now. She walked over to the window. Glanced out. The garden looked tempting. She imagined the cool grass under the soles of her feet, her dressing-gown hem soaking up the damp, the breeze on her skin. Perhaps she’d have a chance encounter with some nocturnal creature: a cat, a fox perhaps, maybe even one of those pesky wolves of her overactive imagination. Isn’t that what always happened when characters in films went on solitary strolls in the moonlight? An image of a beautiful tousled-haired, footsore Reese Witherspoon and her equally beautiful red fox encountering each other in the snowy expanses in Wild popped into Denise’s head.

No! She couldn’t start wandering around the lawn in her dressing gown. That really would be tantamount to accepting that she was going slightly insane.

Denise raised her gaze from the empty lawn. The houses over the road were in total darkness. There was no face at an upper window, no crime of passion taking place for her to observe and become embroiled in. She was a witness to nothing. It was still and quiet and exactly what you’d expect of a good area, with nice neighbours, who – beyond the occasional polite ‘hello’ – kept themselves, and their business, very much to themselves.

Denise pulled herself away from the lack of drama, accepting that she was destined to while away the next couple of hours awake and unaccompanied by man or beast, or at least not by any real ones.

Chapter 2

Thea was late back. Very late. She clattered up the stairwell to her front door and let herself into the apartment. Once inside, she unstrapped her pretty, but excruciatingly uncomfortable sandals and kicked them off. They made a satisfying noise as they bounced along the floor, before coming to rest against the base of the huge brushed-steel plant pot that was artfully positioned in front of the middle window. Bullseye! Able to walk once again without wincing, Thea roved around the apartment switching on lamps, flooding her high-ceilinged, tastefully furnished home in light. There was no one else around to disturb, despite the late hour. Ella was with her father, again. It was, apparently, more convenient for hockey practice. She seemed to be staying with him more and more often these days. Thea crushed that vein of thought before it could start pulsing and pushing the old familiar jealousy around her well-dressed body. Tonight was not about her being a mother and the co-parent of a teenage daughter.

Music! That’s what was needed. Some tunes to prolong the mood.

She chose Beyoncé, ‘Best Thing I Never Had’. Not a bad anthem, at any time of day or night. Thea whacked up the volume, letting her spiritual sister sing out loud and proud. There were upsides to living in the middle of town. The primary one being that she had no real neighbours to speak of or consider. Her apartment sat on top of a row of offices that were empty outside of working hours. Admittedly there was no outdoor space, but there was what felt like acres of space inside.

Thea had found the apartment by pure chance a few years back. She’d been walking past the estate agent on Catherine Street when she saw one of the sales staff in the window adding a new property to the display boards. An architect-designed, newly converted ‘unique living space’ on the High Street, at a price she could in no way afford. Thea’s attention had been snagged. After months of arguing that it was imperative she and Ella stay in the family home, she found herself going inside and asking to view the property. She’d fallen in love with it the minute she stepped over the threshold, negotiated as best she could – given that it was blindingly obvious she wanted the place – and had her offer accepted that same evening, all without saying a word to daughter, or her estranged husband, Marc.

Some things were just meant to be.

Despite the ongoing stress of paying the mortgage, not once in the intervening five years had Thea ever regretted her decision. The apartment was as different from their old house as it could possibly be, but that had been the whole point. A fresh start, of her own choosing, in surroundings with no memories and no associations, 2B The High Street, Harpenden had lived up to its promise. It had gifted Thea light and space, and the perfect mix of privacy with a simultaneous sense of being in the middle of things. Living in the apartment, she found the constant thrum of other people’s lives going on outside reassuring, soothing even. Its position above the action, but not removed from it, gave her connection without direct contact. Most people were unaware that there was residential accommodation above the office fronts. Very few ever looked up and wondered who lived behind the tinted windows on the upper floors of the stylish old buildings that lined the High Street.

So what, if living on a different level from everyone else led to complications.

The day she and Ella had moved in, the removal van had caused a tailback all the way to the Common. Deliveries were a nightmare – parcels ended up left in dustbins or with one of the shop owners. And the parking at the back of the building was a very tight squeeze – hence trading in her much-loved Audi for the Mini. But none of the hassle of town-centre living really bothered Thea, because she loved her new home. It made her feel invincible.

Free of her vertiginous heels, Thea danced around her expensive, but very lovely home, feeling the buzz of alcohol and excitement zipping around her bloodstream.

She had been on a real date.

The first in a very long time.

A nice restaurant.

A nice man.

A nice evening.

Small things, perhaps. No, that wasn’t true – they were big things.

Men paid Thea quite a lot of attention. She had the looks and the attitude that attracted them. In theory she had plenty of options and opportunities, but in reality the type of men who showed an interest in her wanted sex more than they wanted anything else. True, she sometimes wanted sex too, but rarely did she want it badly enough to lower the reassuring barriers that she’d built around herself since her divorce. The couple of drink-oiled encounters that she had gone through with – in hotel rooms far away from her home, her daughter and her professional life – had been okay, but who wanted a life based on okay and the cover of darkness?

Thea shimmied another circuit around the sofas, swaying her hips and shaking her ass – once more for luck. Not that she believed in random good fortune, but she didn’t want to jinx this tentative feeling of excitement and hope.

Tonight she had spent time with a nice man.

A man who seemed to like her.

A man she liked in return.

A man who wasn’t Marc.

For a start, the nice man was taller than Marc – that was a bonus. His height had made her feel dainty. He had the kind of physique that seemed eminently capable of encircling you and keeping you safe. It was so Mills & Boon she should be ashamed of herself, but she wasn’t. He had made her feel feminine, and Thea had liked that. True, the nice man did have hair that was worryingly similar to Marc’s – close-cropped, lightly greying – but that similarity was offset by his totally different face. The nice man had a more prominent nose, slightly thinner lips and less noticeably blue eyes. That wasn’t to say he wasn’t good-looking. He was, just in a different way. Because, somehow, despite his physique, the nice man had seemed slightly less masculine – though not in a bad way. Perhaps that was down to his voice, which, though warm, educated and courteous, was not as deep as Marc’s.

Yes, all in all, it had been a very pleasant surprise that the nice man had been as nice in person as he had seemed on his profile and in his messages, and that was something worth celebrating. Thea threw herself down on one of the sofas and stretched out.

And he had asked to see her again.

He’d come straight out with it, in the middle of the meal, laying his cards face up on the table, no bluffing or faking or playing games. She’d liked that about him as well: the directness. She’d declined to give him an immediate answer, of course. Instead she’d excused herself and gone to the Ladies to… freshen up. A phrase she never used. Coy was not in her repertoire – hard to get, that was a different matter. In the harsh glare of the mirror she’d studied herself, trying to see what he was seeing, to work out what it was about her that was calling to him. In it she saw a woman who looked good for her age, which was forty-nine. Or perhaps good for any age. Almond-shaped, blue eyes. Good brows. It was a strong face with well-proportioned and positioned features. Features she had inherited from her mother. Thea had seen a programme once about the science of attraction and had been proud to be able to tick many of the ‘required’ boxes to qualify as a conventional beauty, totally aware – even as she was congratulating herself – that her face was purely the product of genes.

What were this woman’s faults? Or at least what were her visible flaws? Her internal flaws could wait – wasn’t that the joy of a new relationship, the ability to keep things hidden, at least for a little while? Thea rotated her head through 180 degrees to get a better view of herself. There was her mouth. It was a touch too wide and filled with gappy teeth that 1980s orthodontics had never quite fixed. And there was her nose: it had a bump on the bridge – the legacy of an old hockey injury – that no amount of concealer could conceal. On balance, Thea thought these imperfections added character to her appearance.

But the key ingredient that the mirror captured was confidence. The woman in the mirror met Thea’s scrutiny full on and returned it, with interest. Hopefully it was that strength of character, as much as her conventional good looks, that was intriguing the nice man, who was – as she preened – sitting at their table in the crowded restaurant fiddling with the stem of his wine glass, waiting for her. Thea touched her lips with a dab of colour and adjusted her neckline – in his favour.

She’d returned to the table, slid into her seat and they’d talked on long into the night, convincing themselves of each other’s potential. And as they chatted and sipped their wine, and were sublimely oblivious to the other customers finishing their meals and melting away, Thea had given the nice man, who was not Marc, a hundred small gestures of encouragement, but no actual promises.

At the end of the evening, when the last waiter left standing finally ushered them out of the restaurant and locked the door behind them, she’d declined to allow him to escort her home; indeed, she’d insisted that he didn’t, thereby asserting her independence and protecting, for now, the sanctity of her address.

Beyoncé started in on ‘Sorry’. Thea clicked her off. The apartment fell quiet, or as quiet as it ever got with the almost constant sound of traffic and the sporadic bursts of drunken shouting from the street below. It was time for bed. She had work in the morning. She retraced her steps, turning off the lights as she went. She didn’t extinguish all of them. Thea always left the floor lamp near the front door on. A nightlight for a daughter, who no longer needed it, especially when she wasn’t there.

Despite the late hour, Thea stuck to her routine. She undressed, slipped on her dressing gown, hung up her dress, threw her underwear in the laundry basket and laid her clothes out ready for the morning. She removed her make-up thoroughly, slapped some moisturiser on her face, then brushed her hair twenty times, silently saying goodnight to her mother as she did so. Night-time ritual complete, she climbed into bed and turned off the light.

Thea was reliant on her own body heat to take the edge of the coolness of her king-sized cotton sheets, just as she was reliant on herself for so many things. It took a little while. In the darkness she brought her hand to her face. She followed the bony contours of her cheeks and her nose with her fingertips, explored the smoothness of her cheeks and the fullness of her lips. She ran her fingers along her jaw and down her neck. She lightly stroked the fragile thinness of the skin of her breastbone, before moving on to the soft weight of her breasts.

Gently, slowly, lovingly she traced herself into existence.

She stopped, broke contact with her body, arousal crowded out by more complicated emotions.

She laid her hand on her stomach, let it rest there for a few seconds, feeling her tummy rise and fall. Instinctively her fingertips found the top of the scar. She ran her fingers along the full length of it. Each dent, bump and pucker was as familiar to her as her face. The skin along the ridge was smooth and shiny now, the passage of time reducing the violence done to her to something almost, but not quite, benign.

The scar was her proof of life, but it was also a marker of how close to death she’d been.

She had fought and won.

She had been hurt, but healed.

Whether she’d fully recovered was another matter entirely.

Chapter 3

DENISE WAS on her way out to visit Eric, her father-in-law, when she heard Joe and Lewis in the lounge. She paused, although she really didn’t have the time, hoping to catch what her sons were talking about. Her boys rarely actually spoke to each other, at least not in her presence. They seemed to prefer to communicate physically. Shoves, head slaps, punches, kicks, finger flicks. It was often hard for Denise to tell what was mock fighting and what was real. They’d be casually, amicably sprawling next to each other one minute and battering each other with real intent the next.

It was her and Simon’s fault. Her sons were too close in age. Sixteen months between Aaron and Lewis, fourteen between Lewis and Joe. When Aaron was home from university the brawling ticked up another notch – all of them trying to assert their alpha-male credentials. The amount of testosterone in the house was so high that Denise sometimes thought she could actually taste it.

When they were young, Denise used to watch the mothers with only one child enviously, especially those with daughters. The calm, the sense of peace, the gentleness, was sometimes too much for her to bear as she presided over her pack of sons. It was a jealousy she would have vehemently denied, had anyone commented on it. She’d hoped they would grow out of the physical stuff as they got older, but it hadn’t happened. Indeed, the fierce competition had only grown worse, the contact between them more boisterous. At nineteen, seventeen and fifteen, they behaved like unpredictable children in men’s bodies. She loved them as fiercely as ever, of course, but she felt she understood them less and less as they grew up and away from her.

‘Told ya.’ Lewis’s languid tones.

There was a pause. ‘Yeah. I see what ya mean.’

She disliked their lazy drawl. To her, it seemed put on – a fake to indicate confidence.

‘How old do you reckon?’ Lewis again.

‘Not sure. It’s hard to tell. Have you seen her without her make-up on?’

‘Nah.’

There followed a contemplative silence.

It was Joe who spoke next. ‘Old enough.’

It was the tone as well as the sentiment that shocked Denise. She clumped into the room, deliberately creating a disturbance. The pair of them were kneeling up on the sofa, looking out through the bay window. At the sound of her approach they moved fast – which was a sure sign they were up to no good.

‘What are you doing?’

They both collapsed into liquid-limbed indifference on the sofa. ‘Nothing,’ they said in unison.

She moved towards the window. The new family who’d just moved into number nineteen were unloading a supermarket shop from the car. As the teenage girl lifted out the last bag, there was a flash of taut, tanned midriff. The girl slammed the boot and followed her mum down the side of the house. Denise stared at each of her sons in turn. ‘Well, I’d like you to stop doing “nothing” quite so blatantly and do something more constructive.’ They didn’t move. ‘Now!’

The sharpness of the last word finally provoked a response – albeit a languid one. They unfurled slowly into something resembling an upright position and loped across the room, out of her sight.

In the hall she heard them laughing. She grabbed her jacket from the hook and headed out, one more worry added to her list.

Chapter 4

WHEN THEA arrived, Nancy was dancing to Dean Martin, dressed to impress in a pink satin ensemble, with a jade silk scarf trailing behind her like fag smoke. Only the four necklaces today. She looked perfectly serene as she swayed around her room, bumping into the furniture occasionally. As requested, the staff had pushed everything they could to the edge of the room, to give her mother more room to dance. They were good that way; they tried their best to recognise and accommodate the people the residents used to be, not the ones they’d become. When Nancy caught sight of Thea, she beamed, not with recognition, but with the pleasure of having a guest. Thea was used to it. It didn’t hurt any more. Well, not so much. Thea had brought flowers with her, as she often did. It was an easy shortcut to bring joy into her mother’s randomly spotlit life. Music, flowers, chocolates, perfume – Nancy still like to be courted.

‘Come. Join me,’ Nancy beckoned.

Thea put down the anemones, bought because they used to be her mother’s favourite. They sashayed together around the carpet to Dean’s crooning – Nancy lost in the raptures of her past, Thea doing her best to join her there, through the veil cast by her mother’s dementia. Nancy felt insubstantial in her arms, a paper-cut-out version of her mother. When she laid her head on Thea’s shoulder, there was waft of hairspray, perfume and old age. When she raised her head and smiled, there was the scent of Gordon’s. They danced for five tracks, including the incessantly sunny ‘Volare’, before Thea managed to convince her mother it was time to take a breather, pleading weariness – her own. As she gently guided Nancy to her chair, Thea also contrived to turn down the volume a notch. Frank usurped Dean. One lush followed by another.

‘How was last night?’ Thea asked.

Having smoothed her skirt and patted her hair, her mother drew a fluttery breath, leant forward and began, as she always did, ‘Well…’ – a conspirator’s glance left, then right – ‘there was, I’m afraid to say, something of a furore. Giovanna was not happy. Not at all. And I can’t say I blame her, not after all the effort she’d gone to.’

Thea sat back and listened as her mother told a fluid, but incomprehensible tale of fantasy and glamour with a liberal scattering of random, incorrect nouns and the insertion of the occasional fact. The cold custard and that horrid man with no manners being two such realities. Thea let it wash over her, smiling and nodding at what felt like the appropriate junctures. When the story petered out, Nancy sighed dramatically and raised her hand to her throat. A touch of Dame Margot today.

Thea recognised the signal. ‘Are you thirsty, Mum?’

‘Do you know, I think I may be.’

‘Shall I go and fetch you a tea or a glass of juice?’

Nancy pretended to give it some thought. ‘No. Not tea.’

Thea relented and went over to the mahogany drinks cabinet in the corner of the room. Nancy had insisted that it be transported with her when she’d moved into Cherry Trees, despite its evident inappropriateness and ugliness. Thea opened the drop-leaf front and fixed her mother a weak gin and tonic. The vellum was littered with old ring marks, a ghost map of social gatherings in happier times. Perhaps that was what her mother had been trying to hang on to – not the cabinet itself, but the memories it contained. From her handbag Thea extracted a small Tupperware box. Inside were fresh slices of lemon. Another small treat.

When she passed the G&T to her mother, Nancy glanced at it with both gratitude and a touch of disappointment. ‘No ice?’ She still had her standards.

‘Sorry, Mum. It’s an expensive handbag, but it has its limits.’

Nancy sipped, adding a smear of baby-pink lipstick to the rim of the glass, graciously resigned to a life where her pleasures were curtailed. It was up to Thea to introduce the next, non-taxing topic of conversation. She went with Nancy’s grooming. ‘I see they haven’t been to cut your hair yet?

‘Am I booked in with Harry?’

Harry hadn’t styled Nancy’s hair in more than thirty years, owing to the fact that his salon had been situated in central London, which had become too much of an inconvenience once Nancy stopped going up to town so often; and because he’d been dead for a quarter of a century. Nancy had cried elegantly into a lace hankie at his funeral whilst wearing a hat that would have been more suited to Ascot than a crematorium in Tottenham. But there was nothing to be gained from reminding her mother of this fact. It would only make her sad all over again.

‘No, he’s away on holiday. Barbados, I believe.’ Why not let Harry have some sun, after all this time? ‘But the girl you like is booked to do it.’ Thea had no idea which mobile hairdresser would be visiting the home that week and whether Nancy liked any of them or not, but it was all about positive reinforcement. It would, no doubt, be fine, given that her mother thrived on any and all attention, so long as the hairdresser was true to their profession and a good listener.

‘Ah, yes.’ Nancy joined in the fiction willingly enough. ‘It’ll be Clare. Such a lovely girl. Though she has rather fat ankles. All that standing, I suspect. Does it look a fright?’ She patted her hair like it was a dog that might bite. It did have a touch of Bichon Frise about it.

‘No, Mum. It looks lovely, as always, it’s just getting a little long at the back.’ Change of tack. ‘And have you been going through to the dining room for your evening meal, like we discussed?’

Nancy hid behind her drink, which, given that it was gin and tonic, provided little cover for her fib. ‘Oh yes. Most evenings. Though your father prefers the food at The Metropole.’ Thea smiled. If her father was still squiring her mother out to dinner in her dusty, but seemingly happy memories, so much the better. Her parents had eaten out, or gone dancing, or attended concerts most weekends throughout their marriage. They had had that sort of relationship: dedicated, loving, romantic to the end. Thea felt a rush of affection for her mother’s loyalty to her father. Appropriately enough, a round of applause filled the room. On the DVD player Frank handed over to Sammy Davis Jnr. Nancy set down her glass absent-mindedly. It toppled over and fell onto the carpet. Thea left it there. One of gin’s many benefits was that it didn’t stain. Nancy stood up and reached out her hands. Her nails were newly varnished, a pretty, iridescent pearl colour. Regular manicures were another habit that Thea maintained for her mother. ‘I love this one.’ Nancy’s eyes sparkled cloudily in the sunshine.

And despite the aching boredom that came from having listened to the same DVD a hundred thousand times before, Thea stood up and stepped back out onto the dance floor of her mother’s flickering imagination.

Chapter 5

‘HOW’S HE been?’ Denise asked the same question every time she visited the home, although the answer was never the one she wanted, which was ‘dead’. The horrifying cruelty of wishing her father-in-law gone was merely one of Denise’s dark secrets. She harboured a few such unkind desires, though no one ever seemed to detect the malevolent vein that ran through her – obscured, as it was, by her polite, self-effacing demeanour. This particular ardent death wish reared its head every time she stepped into the overheated lobby of Cherry Trees and braced herself for yet another round with Simon’s seventy-nine-year-old father, Eric.

This was her second visit in as many days. She’d been summoned by an urgent request from the manager of the home, more of a demand really, to supply Eric with supplementary Blu Tack. Karen, the manager, had added at your earliest possible convenience. Politeness and insistence: they were an irrefutable combination. Eric’s preferred method of fixing things to his walls – good, old-fashioned drawing pins – had recently been banned after he’d pressed a tack into the bent head of Cheryl, one of the cleaners. She’d unwisely attempted to pick up some of the ‘paperwork’ that encircled Eric’s armchair like a porch-drop of indoor snow and had been pinned in the head for her trouble. The Blu Tack was a testily negotiated compromise that had created a seemingly unquenchable appetite for the stuff. On the call, Karen had explained that Eric had run out, again, and as a result had been getting ‘very agitated’ about his inability to make headway on his ‘project’. This, to the ill-informed observer – namely, anyone brave enough to enter his room – appeared to be a commitment to cutting out every single article on military spending in Europe, the Balkans, Russia, Japan (his interest was old-school but global) and annotating these articles with a spider’s web of comments and calculations. His aim being to demonstrate that the UK was woefully unprepared for the next big conflict, which he repeatedly predicted was only a matter of time. These scribbled-on articles were then stuck around the walls of his room in classic crime-drama fashion. Unfortunately, with the recent move to a bigger room, Eric had upscaled his efforts.

It was costing Denise a fortune in newsprint, Blu Tack and, most importantly, time.

Julie, the care assistant, shrugged, ‘Same as usual.’ Julie was one of the most tolerant, more experienced members of staff. She must have seen and put up with it all before. ‘Though he did comment on the size of my arse this morning. And it wasn’t a compliment.’ Denise instinctively apologised, but Julie flapped the ‘sorry’ away with her small, blue-gloved hands. ‘Shall I bring you both a cuppa?’

Her kindness caused a rush of tears to fizz up Denise’s nose. She turned away, embarrassed. These bouts of sudden emotion – sadness and rage, about the smallest of things – were increasing in number and unpredictability. ‘No, you’re busy. I’m not staying long.’ She vehemently hoped this was true as she tapped on Eric’s door.

‘What?’ he shouted.

She took this as her invitation to enter.

The room was worse by 10 per cent than it had been when she’d last visited on Tuesday. It wasn’t just the mess, she was used to that; it was the frenzy reflected in the mess. The chaos Eric created around him spoke of frustration and anger, of things not dropped absent-mindedly, but hurled with intent. As always, this physical display of his distress enabled Denise’s sympathy to scramble over the top of her irritation. Eric hated being old – detested it – and, as a result, his furious response guaranteed that everyone who came into contact with him also had a hateful time. Which impacted on people’s willingness to visit, which increased his isolation, which made him more miserable, et cetera, et cetera. It was the true definition of a vicious circle.

‘Afternoon, Eric.’ Denise stepped into the room warily, nervous of disturbing some pattern of paperwork that only he could discern in the layers of stuff on the carpet. She left the door open, preferring to be able to see out, and be seen by the passing staff.

‘Have you brought it?’ He held out his hand, blue veins bulging beneath his crêpy skin. She dug the Blu Tack out of her handbag. He snatched at it and proceeded to count the packets. ‘Is this all they had? Five packs!’ She had thought it a lot. ‘It’ll have to do for now. But I’ll be needing more, with the Spending Review coming out next week. Can’t you bulk-buy the stuff? It’d save time, and money.’

‘I’ll look into it.’ Placatory – that was the way to go, with her father-in-law.

Minimally satisfied by her offering, Eric put aside his new supply on top of a pile of papers and fumbled open a pack. He pulled a lump of Blu Tack off the sheet and began rolling it between his fingers. Denise noticed that his nails needed cutting, but quailed at the thought.

‘How’s it going?’ She had to ask. This was his ‘work’ now, and not asking was tantamount to disrespect.

‘I’m making progress, but the review will stir up a shitstorm, so I want to be ready for it. The head of the MOD is already doing the rounds, setting his stall out. They’re obviously not happy.’

Denise nodded as if she had some clue what he was talking about – but not enough, obviously, to offer a valid opinion. Eric was used to women who were seen, not heard. Simon’s mother, Maggie, had fulfilled that brief perfectly. Even her death had been a quiet affair: a soft crumpling onto the kitchen floor in the middle of crimping the edge of an apple-and-blackberry pie. A massive heart attack at the age of sixty-five. No one heard her fall. Eric, who eventually found her when he went in search of his lunch, had been devastated. But his genuine and heartfelt sorrow had not softened him. Instead, his grief had hardened around him like a carapace. And with every year that passed of his miserable, lonely, angry old age, it seemed to grow thicker and sharper.

It was all very sad.

It was also a major pain to have to deal with on a regular basis.

Denise wondered if leaving within five minutes of arriving was acceptable and knew it was not. You had to sign in and out of the home – a public register of familial duty observed. Added to which Eric’s new room was, unfortunately, just across the corridor from the communal lounge, and so the brevity of her stay would be noted by the ever-vigilant staff. When your family member was on the ‘challenging’ end of the spectrum, you were expected to share the load.

Karen had positioned the room switch as a way of giving Eric more space for his project, but Denise suspected it had more to do with the staff wanting to keep a closer eye on his interactions with the other Cherry Trees occupants. Her father-in law’s drive to proselytise was rarely met with much enthusiasm. Quite naturally, most of the residents preferred conversations about gardening and the royals to diatribes on the dangers of reduced defence spending. Eric’s loudly voiced categorisation of his neighbours as brain-dead also did little to endear him to them. And when, as it inevitably did, Eric’s rudeness caused serious offence, it always fell to Denise to deal with the problem – Simon’s relationship with his father being too combative for him to bring up the old man’s intolerance. These increasingly necessary, painfully awkward ‘little chats’ about Eric’s behaviour never went down well. At least today she wasn’t having to tackle his rudeness head on, merely live with it for half an hour or so.

Denise accepted her fate and moved a stack of books off one of the chairs. ‘May I?’

‘Give them here.’

She passed him the pile and sat down. ‘How have you been keeping, Eric?’

‘You asked me that on Tuesday. Nothing’s changed in the space of two days.’ Small talk was not one of Eric’s fortes.

‘Yes. You’re quite right, I did – sorry.’ But what the hell else was there to say? So she lied. ‘Simon and the boys send their love.’ For a second the old man paused in his restless wandering. His faded blue eyes settled on her and she felt a draught of discomfort and sympathy. Eric might be old, but he wasn’t stupid. She rushed on. ‘The gardens are looking nice. Do you fancy a walk? Outside,’ she clarified pointlessly.

‘The grass will be wet. I don’t want my turn-ups ruined.’

‘Okay.’ She cast around for another topic and found herself struggling. Her attention wandered. Through the open door she heard music. Sinatra whooping it up in New York. ‘Sorry, Eric.’ She had missed a question.

He came and stood over her – making the most of his still impressive six-foot-plus height. Simon had inherited his father’s stature. Denise wondered, with an involuntary shiver, whether he would develop the same short fuse.

‘I asked about the business,’ he said testily. ‘Did Simon get that problem with the US supplier sorted?’

Mather’s had been set up by Eric. It represented his life’s work. He still held a non-exec director title, out of respect. Denise had told him about the issues they’d been having with a supplier in San Francisco, as a distraction when she’d last visited. There was nothing wrong with his memory, just his grasp of her role in the business. ‘It’s being sorted.’

Eric did not look convinced by her reassurance. ‘Simon needs to be careful they’re not shafting him. They’re renowned for it, the Yanks. They think we’re all wet behind the ears.’

‘I’ll mention it to him,’ Denise said. She obviously had no intention of doing so. Simon had endured more than his fair share of his father’s advice and guidance over the long years they’d worked together. His relief when his father had finally retired, after considerable pressure to do so, had been immense. That fraught period went some way to explaining Simon’s reluctance to spend anything other than the bare minimum of time with his father now – explained, but did not excuse it. She glanced at her watch. Had she really only been in his room fifteen minutes? She felt her phone burr in her bag: another missed work call. But she didn’t get it out to check. Eric had a passionate hatred of mobile phones, as he’d forcefully demonstrated a couple of months back when she’d got sucked into a long conversation about an issue with a shipment. She’d been so intent on resolving the problem that she’d forgotten to keep an eye on the old boy. Her shock when he’d ripped the phone out of her hand and hurled it across the room, smashing the screen in the process, had been intense. In an immediate reflex attempt to calm things down, she’d been the one to apologise for taking the call in the first place.

Eric had resumed his patrolling around the room. He stopped every now and again to peer at one of the cuttings plastered on the walls. The image an old lion pacing up and down the bars of his cage came to Denise. It was the same restless toing and froing, with no real purpose. She saw her ‘get out’ and took it. ‘Well, I can see you have a lot to get on with. I’ll not disturb you any longer. I’ll look into a bulk-buy of the Blu Tack, as you asked.’ It was just like the old days when he’d been her boss. Family businesses! If only she’d known about their very persistent and peculiar challenges when she’d first offered to help out in the office. She stood up. ‘I’ll call in again next week, Eric.’

He switched his attention back to her, briefly. Nodded, curtly. ‘Very well.’ Then he resumed his circuit.

Dismissed, she made a hasty exit, relieved to have fulfilled her duty – until next time.

Out in the corridor she heard clapping, followed by someone whistling. The whistling gave way to the swell of violins, then Sammy Davis Jnr began crooning ‘Mr Bojangles’. The music wasn’t coming from the residents’ lounge, as she’d first assumed; it was coming from one of the rooms further along the corridor.

Denise didn’t mean to intrude, but, with the door open and the strains of a full orchestra drifting out, it was only natural to glance inside as she made her way past. What she saw made her smile. An elegant old lady, wearing a pink dress, dancing with someone who had to be her daughter. The two women were spotlit by the sunshine streaming in through the big bay window. The daughter held her mother in her arms with real tenderness as they swayed together to the music, eyes closed, full of grace, in a world of their own making.

It was such a picture of contentment that Denise stopped and watched them for a few seconds, before turning away.

Chapter 6

THEY WERE