Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

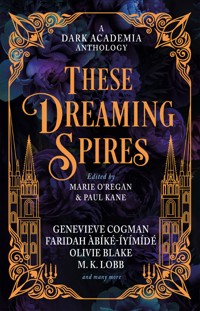

A NEW SEMESTER BEGINS A beguiling, sinister collection of 12 more dark academia short stories from masters of the genre, including Olivie Blake, M.L. Rio and more! Twelve original dark academia stories from bestselling thriller writers – imagine darkened libraries, exclusive elite schools, looming Gothic towers, charismatic professors, illicit affairs, the tang of autumn in the air… and the rivalries and obsessions that lead to murder. Featuring stories from: Olivie Blake Genevieve Cogman Ariel Djanikian Elspeth Wilson MK Lobb Jamison Shea Kate Alice Marshall Erica Waters De Elizabeth Taylor Grothe Kit Mayquist Faridah Àbíké-Íyímídé

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 483

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Introduction | Marie O’Regan and Paul Kane

Tallow’s Cove | Erica Waters

Utilities | Genevieve Cogman

Destroying Angel | Jamison Shea

Within the Loch | Elspeth Wilson

Advanced Dissection | Taylor Grothe

God, Needy, Enough with the Screaming | Olivie Blake

Poisoned Pawn | De Elizabeth

Open Book | Kit Mayquist

A Short List of Impossible Things | Faridah Àbíké-Íyímídé

The Harrowing of Lucas Mortier | M. K. Lobb

The Coventry School for the Arts | Ariel Djanikian

The Magpies | Kate Alice Marshall

About the Authors

About the Editors

Acknowledgements

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

FANTASY

Rogues

Wonderland: An Anthology

Hex Life: Wicked New Tales of Witchery

Cursed: An Anthology

Vampires Never Get Old:Tales With Fresh Bite

A Universe of Wishes:A We Need Diverse Books Anthology

At Midnight: 15 BelovedFairy Tales Reimagined

Twice Cursed: An Anthology

The Other Side of Never: Dark Talesfrom the World of Peter & Wendy

Mermaids Never Drown:Tales to Dive For

The Secret Romantic’s Book of Magic

CRIME

Dark Detectives: An Anthologyof Supernatural Mysteries

Exit Wounds

Invisible Blood

Daggers Drawn

Black is the Night

Ink and Daggers

Death Comes at Christmas:Tales of Seasonal Malice

SCIENCE FICTION

Dead Man’s Hand:An Anthology of the Weird West

Wastelands: Stories of the Apocalypse

Wastelands 2:More Stories of the Apocalypse

Infinite Stars

Infinite Stars: Dark Frontiers

Out of the Ruins

Multiverses: An Anthologyof Alternate Realities

Reports from the Deep End:Stories Inspired by J. G. Ballard

HORROR

Dark Cities

New Fears: New Horror Storiesby Masters of the Genre

New Fears 2: Brand New HorrorStories by Masters of the Macabre

Phantoms: Haunting Tales fromthe Masters of the Genre

When Things Get Dark

Dark Stars

Isolation: The Horror Anthology

Christmas and Other Horrors

Bound in Blood

Roots of My Fears

THRILLER

In These Hallowed Halls:A Dark Academia Anthology

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

These Dreaming Spires

Hardback edition ISBN: 9781835410196

E-book edition ISBN: 9781835410233

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: September 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Introduction © Marie O’Regan and Paul Kane 2025

Tallow’s Cove © Erica Waters 2025

Utilities © Genevieve Cogman 2025

Destroying Angel © Jamison Shea 2025

Within the Loch © Elspeth Wilson 2025

Advanced Dissection © Taylor Grothe 2025

God, Needy, Enough with the Screaming © Olivie Blake 2025

Poisoned Pawn © De Elizabeth 2025

Open Book © Kit Mayquist 2025

A Short List of Impossible Things © Faridah Àbíké-Íyímídé 2025

The Harrowing of Lucas Mortier © M. K. Lobb 2025

The Coventry School for the Arts © Ariel Djanikian 2025

The Magpies © Kate Alice Marshall 2025

The authors assert the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Typeset in Minion Pro.

EU RP (for authorities only)eucomply OÜ, Pärnu mnt. 139b-14, 11317 Tallinn, [email protected], +3375690241

INTRODUCTION

Marie O’Regan and Paul Kane

Believe it or not, this volume of Dark Academia short stories – a sequel of sorts to In These Hallowed Halls, which featured the likes of Kate Weinberg, M. L. Rio and Susie Yang – was commissioned even before that first book came out.

Such was the interest in Hallowed Halls, with pre-publicity and ARCs requested, and just pure excitement reaching a fever pitch in the run-up to the first ever Dark Academia anthology being released. It has since been reviewed incredibly well and sold for translation to several other countries, such as Poland and Turkey.

Looking back on that wonderful time and seeing all the buzz for this project online – not to mention going out and doing signings – it will always be a very special time in our lives, and probably in the authors’ lives as well.

Our aim wasn’t just to provide something which hadn’t been created before, but also to push the boundaries of what Dark Academia might be – and this was definitely reflected in some of the reviews. We soon realised, even after setting out a potted history of the phenomenon in our introduction and trying to give an overview, that it means very different things to different people; some deeply personal. There always has been much debate about what constitutes Dark Academia, what it should and could be, and our intention was to include pieces that covered the widest possible range of those types of tales. It’s something we try to achieve in all our anthologies.

Similarly, with These Dreaming Spires we were looking at doing the same – maybe even pushing those boundaries a little bit further. That’s not to say we wouldn’t be including more traditional elements of the subgenre, as we definitely did with the original book, but also that there’s always room for more innovative examples of what it means to particular authors.

So, what lessons have we got for you this time round?

Elspeth Wilson (These Mortal Bodies) brings us a tale about memories, the environment and a unique body of water connected to a seat of learning, and Erica Waters (All That Consumes Us) introduces us to a place where the patterns of the past can be very perilous indeed. Genevieve Cogman (The Scarlet Revolution trilogy) presents an all-too-believable technological nightmare for one poor student, while Kate Alice Marshall (We Won’t All Survive) concerns herself with the notion of reality itself.

Author of The Prospectors, Ariel Djanikian, relates a story of one girl facing up to tragedy – which also informs a tale from M. K. Lobb (To Steal from Thieves), asking us what we would give for “higher” knowledge. The author of Where Sleeping Girls Lie, Faridah Àbíké-Íyímídé, asks us to think about just what is impossible, and Taylor Grothe (Hollow) about the survival of the fittest – or should that be the most ferocious?

In Jamison Shea’s (I Am the Dark That Answers When You Call) contribution we find out why it can be dangerous to encounter your true soulmate, while De Elizabeth (This Raging Sea) is inspired by the twists and turns of chess. The author of Tripping Arcadia, Kit Mayquist, presents us with a tale of a mysterious ancient tome, and Olivie Blake (The Atlas Series) delivers a meditation on madness and obsession.

Get ready to go to the top of the class, people, because a brand-new term is about to begin…

Marie O’Regan and Paul KaneFebruary 2025

TALLOW’S COVE

Erica Waters

My first thought was that I wished I’d come earlier. It was only half past three, but already the day’s last light was leaving the cove. That light ought to have gilded the salt marsh and cast its golden glow on the shoreline, illuminating St. Clement’s College Chapel and picking out the details of the sagging colonial houses scattered on the other side of the shallow water. But the light didn’t seem able to touch Tallow’s Cove, which remained as dull and desolate as the wet New England weather.

The chapel, strangely isolated from the bustling campus, seemed more like a piece of the landscape, as if it had grown right up out of the sandy soil, building itself from the gray, lichen-covered boulders that were scattered across the shore. It was a creature of salt and stone, hulking where it ought to have soared. Its belltower listed nauseatingly toward the sea.

I was only a few minutes’ walk from the student union, with its mediocre café and noisy air hockey tables, yet I felt like I had wandered out of ordinary life and into a myth, like a knight who stumbles upon a castle under a spell, where a wounded king lies waiting to be healed. Everything was still, almost stagnant. The path from town to the cove had long since been washed out by coastal flooding and neglect, so only members of the college had easy access to it, but I was still surprised by the emptiness of the place. There were no dogs running on the shingled beach or elderly women scanning the skies for birds, no amorous co-eds making out on a blanket. It was November, sure, and a blustery cold day, but during my undergrad years in Boston, I had learned that the determination of New Englanders to be out in all weather was as reliable as the tides.

I was here on a research trip, having won a highly coveted semester-long travel grant to do research for my MDiv thesis, which purported to explore haunted religious spaces in the US as representations of historical institutional wrongdoing. This was the fifth such place I had visited, following online tips that had led me from Georgia to Tennessee to North Carolina to Pennsylvania to Massachusetts. In each place, I had taken photos and collected accounts from locals, digging into local archives where I could. I had not encountered any restless spirits, but I did uncover the ghosts of America’s sins, just as I had expected: racism, homophobia, consumerism. Those places had indeed been haunted, but not by any actual spirits, merely the reverberation of ordinary, banal human evil.

But this place… if any religious sanctuary might turn out to be haunted by something otherworldly, I would put my money on St. Clement’s Chapel. It looked too… too something, though I couldn’t put my finger on it. Not yet.

The only thing that moved on the horizon was the seagulls, which screamed and circled, smudges of white against the darkening sky. I paused for a long moment to watch as one of the gulls flew straight up into the air, a snail or some other hapless invertebrate clutched in its talons, and dropped the poor creature on the rocks below, cracking open its shell, before swooping down to retrieve the tender meat. I shivered, drawing my corduroy blazer tighter, and scanned the water for any other signs of life. From far away came the sound of a buoy, its distant ringing like a mournful church bell. But there were no boats out in the cove. Close to shore were a handful of geese in the shallow water, all in a line. Each bird had its head tucked beneath a wing, as if sleeping or hiding from the relentless wind, which stung my eyes and made them water. Other than the gulls and the geese there were only rocks and a single skeletal tree thrusting out of the high bank that led to the chapel. My feet seemed to carry me toward it of their own accord.

Up close, the chapel seemed even more off-kilter, more damaged – a place left to rot until it fell into the sea. The front doors had clearly once been painted red and were still studded with iron, but now they were decayed and covered in mildew, barely attached to the hinges. Wary, wanting to get my bearings before I went inside, I walked around the building to the churchyard, where the overgrown remains of a small cemetery quietly moldered. The headstones ranged from the mid-1700s to the early 1900s, most of the stones cracked and broken, covered in lichen and moss, nearly illegible. I squatted to examine a row of them. The nearest showed a hand with its finger pointed at the sky. I couldn’t make out the inscription. Later, I would take pictures of everything, but I liked my first impression of a reputedly haunted location to be unmediated, unfiltered, nothing between me and the building I had come to research.

I stood with a wince, regretting forcing my always-stiff joints into a crouch, and stared up at the rubblestone granite building, my skin prickling strangely as if I were being watched. I shifted my leather satchel on my tired shoulder and scuffed my chunky oxfords on the gravel in the overgrown grass, drawing out the moment before I would go inside and face whatever was lurking, whatever was giving me that feeling of eyes on the back of my neck. I sensed there was a reason I had saved this stop for last.

Of course, I had found out the basic facts of the place before my arrival, partly from St. Clement’s website and partly from the blog of a recently deceased local historian. It was originally built by early colonial settlers, a small Anglican church in a Puritan stronghold, funded by a rich merchant who remained loyal to the British king. As the American Revolution approached and tensions became increasingly volatile, patriots were said to sneak up into the gallery to spit on the heads of the worshiping Tories. Windows were broken by local boys throwing rocks for sport. Finally, the wooden church was burned down by a group of angry Puritan men, who saw no place for the old English ways in their new world. The church’s priest, the Reverend Samuel Tallow, refused to leave the building and burned with it.

After the Revolution, a wealthy relative of Tallow’s had the place rebuilt in her cousin’s memory. A new priest arrived. The bell from the original church was refurbished and set to ringing in the new belltower. A large plaque devoted to Father Tallow’s memory was erected in the vestibule, a stone relief depicting his face in profile. He looked out over the new church and its congregation, a man who had martyred himself now an unofficial saint of the place.

It all seemed hopeful, like a sign of the new world freed from British rule and from religious tyranny alike. But the church couldn’t seem to keep a minister there for more than a few months, and eventually the local community dwindled. The church was closed up. Then, in the early 1900s, St. Clement’s University was built up around it and it became a chapel for the students.

Now, nearly two hundred years after its construction, it looked liable to fall back into the sea whose riches had built it. Stones were missing from the façade, and several of the arched stained glass windows had been broken, their remaining panes dull red and blue in the fading light. It was strange to see a church so abandoned, here in New England where history was everything. I was used to the sight of such things in the South, where people are always so eager to forget, to build over, to bury. I’d seen dozens of little lost churches scattered on dusty highways back home. But here, where there was so much money and ancestry, you didn’t often see historical buildings like St. Clement’s abandoned and left to rot. I was puzzled that the college hadn’t taken more pains to preserve and protect it.

I felt a sudden unexpected pinch of kinship with the chapel, an ache behind my breastbone whose origin I couldn’t place. Maybe it was because I had been on the road for months and I was tired. Maybe my body, playing host to a progressive inflammatory disorder that threatened to destroy my spine, joints, and connective tissue, felt a little too much like that run-down chapel. But I suspected it was more a spiritual ache than a physical one. The truth was that my travels had shaken me right down to my foundations, exposing all the cracks and structural weaknesses of my faith and my calling.

With a resigned sigh, I left the dead to their dreaming and walked back to the front of the chapel where the once-red doors listed on their hinges, threatening collapse. I was surprised they weren’t boarded over to keep out curious undergrads. Yet another irregularity.

Gingerly, I tried the one on the right, easing it open just enough to slip through into the darkness on the other side. I turned on my phone’s flashlight and used its beam to climb three steep stairs up into the nave of the chapel. My light fell on Tallow’s memorial, his expression seeming to blaze from the marble even as lichen crawled across his cheek – as if St. Clement’s was swallowing him up in a second death. I turned away.

Weak gray light filtered in through the stained glass windows, barely enough to illuminate their subjects and certainly not enough to light the chapel. I could feel rather than see the immensity of the place, the rafters arching high above me. I pointed my flashlight straight down the aisle toward the altar. Its beam wouldn’t reach quite that far; it died somewhere in the distance, showing a narrow band of dusty floor and empty box pews, some of their doors hanging open.

I turned off my flashlight and walked slowly toward the altar, genuflecting out of habit. As my eyes adjusted, I began to make out more details. I had expected to find the altar ransacked, but it looked eerily untouched, the altar linen and silver still in place, covered in a thick layer of dust. A dead sparrow lay feet-up beside the communion cup. It looked as untouched as everything else, clean and whole, no signs of rotting.

I picked up the bird and cupped it gently in my hands, trying to remember why I had wanted to become a priest. The last few months had nearly obliterated that desire.

Perhaps I’d started on this path because I was a queer person of faith with too much to prove; wearing the collar would be like a divine stamp on my person, saying I was good, I was whole, there was nothing broken inside me. Maybe it was because I loved the beauty and strangeness of the liturgy, the sense of time stretching out for thousands of years, an unbroken chain of people striving for something beyond themselves. Maybe it was just because I was lonely and being a priest would allow me to be in tender contact with people who needed me. Maybe it was all of those things.

But right now, none of those reasons seemed to be enough. Not in the face of all I had been forced to reckon with these last few months. It wasn’t that I hadn’t known all the harm done in the name of religion – of course I had. I’d studied church history. More importantly, I was a queer person who’d grown up in a poor rural community whose churches preached that I was going straight to hell. But seeing the indelible marks left even on wood and stone…

I wondered if I should bother finishing the degree. My calling felt as fragile as the tiny cold sparrow cupped in my aching hands.

As if in answer to the thought, I felt the faintest pulse against my palm. I flinched, my fingers opening by instinct. I fumbled, trying to catch the tiny body before it fell to the floor, but feathers brushed against my fingertips as the sparrow darted up, landing on the thurible that hung from the ceiling, sending out the faintest whiff of ancient incense.

I gasped, the sound unnaturally magnified in the hush of the chapel. Had the bird only been stunned? Perhaps it had smashed into something right before I entered the chapel, and my hands had warmed it enough for it to fly again?

That must be it. Despite my plans to become a priest, I did not believe in miracles. My faith was made up of words, metaphors, and the concrete rituals of the Eucharist: altar linen, memorized prayers, a silver cup lifted to drink. But a shiver went through me all the same.

I watched the bird for a long moment as it sat preening itself, seemingly unharmed. Only when it flew away did I turn, surveying the empty chapel, studying every detail I could make out in the low light. The sense of being watched had disappeared once I came inside. Yet it still ought to feel threatening, shouldn’t it – this twice-abandoned place? But it didn’t. That was what was strange. Unlike the other so-called haunted churches I had visited, this one, despite feeling much more haunted, did not feel unsettling. It didn’t set my teeth on edge, didn’t make me feel sick at heart like the others had.

In fact, it felt familiar. It felt like kin.

That should have been enough to warn me away, but it wasn’t. I took out my Moleskine and started writing.

* * *

The history department had loaned me a small, windowless office the size of a closet for the duration of my stay. It was more than generous; the beleaguered adjuncts in the liberal arts wing had far less, sharing an office between the ten of them. I used the space only occasionally, preferring to work in the library, with its huge neo-Gothic windows and green reading lamps. But I had put out a call for locals and students who had stories about the chapel’s hauntings, promising an anonymous, private space for the interviews, so I would use the stuffy office to meet with the handful who were willing to talk to me about their experiences.

My first meeting, just after lunch, was with a graduate Art History student who had written a paper on “religious imagery in nineteenth-century stained glass” the previous semester. She had sent me a brief, reserved email that had immediately caught my interest. Often, people who were eager to talk about their paranormal encounters were the least credible. But the ones like Arbor Jones, who were clearly embarrassed, skeptical of their own experiences, yet felt compelled to share, those were usually the ones with something worth hearing.

Arbor’s eyes widened very slightly when she came in and saw me. I wasn’t what she’d expected: young and obviously queer with my shorn hair, thrifted menswear, and tattoos. But she had surprised me too. From her email, I had expected someone chic, well-dressed, a little preppy – a future museum curator. Instead, Arbor had a shaggy, light pink wolf cut and heavy black boots, and razor-sharp eyeliner which gave her soft face a decisive expression that matched the email I’d received.

“Come in,” I said, waving her to a chair with a cracked green vinyl cushion on the other side of my desk, which was piled high with Xeroxed papers and library books. “Arbor? I’m Lana Waldron. You can leave the door open or close it, whatever you prefer… Sorry it’s a bit tight in here,” I added as she squeezed through the small space between the chair and the door, which she closed with a quiet click.

“That’s all right,” Arbor said. “The academic life.” She noticed my handheld recorder on the desk. “You can record if you want, I don’t mind,” she said, before I could even ask. Her accent was neutral, giving away nothing, exactly the kind I envied as a Southerner with the sort of hard-to-hide drawl that was a liability in academia. She pulled a battered, pin-covered messenger bag onto her lap. I noticed her pansexual Pride flag pin and she noticed me noticing. She smiled.

“Can gay people be ministers now?” she asked after I pushed the record button.

“In the Episcopal Church and a few others they can,” I said. “But I’m still a student. Not wearing the collar yet.”

She nodded. “Not really my area,” she admitted.

“But you wrote about religious imagery in stained glass,” I prompted her.

“I was curious,” Arbor said. “I didn’t grow up in church, have hardly ever even been inside one. I’m an atheist,” she added, “but if you want to study Art History, religion is an inevitable part of it. And there are useful archetypes there like anything else. And I felt kind of… I don’t know, kind of drawn to the chapel? I was curious,” she said again.

“So you’ve spent some time in the chapel? What did you think of the stained glass?” I asked, hoping to set her at ease by talking about her academic interests before launching into her paranormal encounter.

“Well, it was badly damaged, at least some of it. They haven’t taken care to preserve it properly. But what’s still there is beautiful.”

“How much time did you spend in the building?”

“At first, it was just going to be a few days, several hours at a stretch. I was sketching,” she said. “I tend to get absorbed, lose time a little when I do that.”

I nodded, eyes on my notebook as I took notes.

“But…” She hesitated. “But I spent the night a few times.”

I looked up sharply. “Why?”

“I, uh, couldn’t pay my rent for a bit,” she said, uncomfortable now. “I lost my job. Called out sick one too many times. Long Covid.”

“Definitely been there,” I said. “Not Long Covid but also an inflammatory thing, autoimmune. Makes work-life balance a challenge, doesn’t it? I had to take a whole semester off last year.”

Arbor visibly relaxed and began to talk more freely. “I figured it would be like camping out, you know? And then I could study the stained glass at all different hours, take pictures, really soak it in.”

“Was it frightening being there alone at night?”

She shook her head. “It should have been, but it wasn’t.”

“What do you mean?” I asked, though I suspected I already knew.

She shrugged, and I sensed she was going to clam back up, so I quickly moved on. “Did you see or hear anything unusual?”

“No, it wasn’t like that. There weren’t, like, Bibles falling from the ceiling or demonic voices whispering to me. Not like a horror movie or anything.”

“So what, then?” I prompted, leaning forward.

She sighed. “It’s hard to explain.”

“Take your time.”

She fiddled with the beaded bracelets on her wrist. “I started taking care of the place. Like, sweeping the floors, polishing the… the cross thingies. The candelabras.”

“Why?”

She shook her head, gave an embarrassed half-smile. “You know how pregnant women talk about nesting? It kind of felt like that, only there was no baby coming, nothing special to do it for. I just felt… compelled. I needed to do it.”

“Hmm,” I said. “Maybe the art historian in you, some desire to conserve?”

She shook her head. “No, it was more than that. I—It went on like that for weeks, me sleeping there and working on the place. It got so bad that it was hard for me to leave and go to class. Hard for me to stay away for more than a few hours. My girlfriend at the time got pissed and broke up with me.”

“Oh, wow, I’m sorry,” I said. “It sounds like the chapel exerted a lot of power over you.” I wasn’t entirely convinced that this wasn’t some private mental health issue, an unusual manifestation of agoraphobia perhaps.

She must have seen something of those thoughts on my face because she leaned forward, elbows on her knees. “I had done everything I could for the floors, for the pews, for everything that could be cleaned or polished or aired out. And then I started on the windows.”

“How? They’re so high up… thirty feet at least.”

“I stole a ladder from the maintenance department,” she said with a quick laugh.

I raised my eyebrows.

“I had to do it. I had to do it even though I’m scared of heights. Even though I get vertigo.”

My stomach clenched. I thought I knew where this was going.

Arbor’s face took on a fierce, determined expression. I imagined it was how she had looked while she climbed. “I closed my eyes while I went up. All the way up, one rung at a time, a bucket of soapy water in the crook of my arm. And then there were no more rungs. I was at the top. I started washing the window on the right front part of the church, the blue one with the dove? And even though I was terrified, even though I felt dizzy and sick, I felt like I was doing the thing I was born to do, like nothing mattered more than that. But then…”

I held my breath, waiting.

“Then I reached too far and I lost my footing and I fell.”

I gasped, covering my mouth with my hand.

Arbor’s green eyes bored into me, intense and insistent. “I remember the fall, the way the air whooshed around me. And I remember hitting the floor. My head burst with pain, my entire spine seemed to crack open. It was a single split-second of agony.”

Involuntarily, I scanned her body, looking for evidence of wounds, of breaks, of damage. There were none. She shouldn’t even be alive. Or she should be in a hospital bed, her back broken, her brain a swollen mess.

“I died,” she said simply. “I know I died.”

“But…” I had no words. I was treading dark water, with no idea what lurked in the depths.

“Aren’t you supposed to believe in miracles? Isn’t that kind of your whole thing? Jesus healing the blind man? Jesus raising Lazarus from the dead?”

“What happened next?” I asked, ignoring her questions. My heart beat hard and fast, and sweat beaded on my upper lip.

“I woke up the next morning on the floor, and I was fine. No injuries at all. Nothing. Not even a bruise on me.”

“Are you sure you really fell? You didn’t dream it?”

“I was lying under the ladder. The bucket of water was spilled on the floor. There was a board under me that had cracked. It wasn’t cracked before. I know it wasn’t cracked before because I had scrubbed that damn floor on my hands and knees,” she added as if anticipating my argument. “I fell. I died. And then I wasn’t dead.”

I thought of the bird that had stirred to life in my hand the previous day, of the way its feathers ruffled against my skin. The hairs on my forearms and along the nape of my neck stood on end.

“Why?” I asked. “Why do you think it all happened?”

Arbor shook her head. “I wish I knew.”

“Have you ever been back?”

She gave another shake of her head. “Never. I got up off the floor and I ran straight out of there. I never went near it again.”

“So the compulsion was gone? To take care of the place?”

She laughed, though it was a strangled kind of sound. “Died with me, I guess.”

I studied her. This was an educated person, a self-avowed atheist. I didn’t think she was lying. How could it possibly benefit her? But that didn’t mean any of this was true. It didn’t mean she hadn’t had a serious mental health episode. Those were common enough in grad school. I had watched plenty of classmates spiral into depression, anxiety, mania. If she was already sick, if she had lost her job and was under stress…

“Did you ever look more into the chapel’s history?” I asked, eyes on my notebook again as I doodled a bit of ivy in the margins of my notes, not wanting to give away my thoughts by meeting her gaze once more. My facial expressions have always tended to be too open, too communicative. I didn’t want to piss her off or make her feel like I didn’t believe her.

“No. I thought about it, but I decided the best thing to do was to put as much distance as possible between me and that place. I didn’t want it to pull me back in.”

It occurred to me then that she spoke about the chapel as if it were a person; sentient, with a will of its own. Maybe to her it was.

“You’re… you’re not going to spend too much time there, are you?” she asked, her tone strange.

I looked up and met her eyes.

“You’re not going to stay the night, are you? Don’t stay the night,” she added. “You should take someone with you, too. Someone to keep you balanced.”

“I’ll be okay,” I said. “I’ve been studying reputedly haunted places for months.”

“Not like this, you haven’t. That’s the only reason I came to be interviewed. I wanted to warn you. I didn’t want you to end up like me.”

“But you’re okay now, aren’t you?” I asked carefully. “You weren’t permanently injured?”

She shrugged. “I dream about it a lot. The chapel. The fall. I relive it. For a while, I thought about transferring to a different school to get away from it.”

“Why didn’t you?”

She bit her lip. “I have too much here, too much to lose, so I just don’t go anywhere near it now. And you shouldn’t either,” she said, standing and gathering her things. “You should keep it purely academic. Don’t get involved.”

“I’ll bear that in mind,” I said, rising to walk her to the door even though it was only a few feet away. “Thank you for telling me your story.”

“You’re welcome,” she said, formal again. “Goodbye.”

“Oh, Arbor,” I called, when she was halfway down the hall. She turned. “Could I read your paper about the windows?”

“I never wrote it,” she said. “Took an Incomplete. But I still have my sketchbook. I’ll put it in your mailbox tomorrow.”

“Thanks. I promise to return it.”

“You can keep it,” Arbor said. “I don’t know why I’ve hung on to it all this time.” She gave me the barest of smiles before she walked away.

* * *

I had interviews scheduled with five other people over the next two days. Four of them turned out to be undergraduates with a flair for the dramatic, their stories about drunken dares and shadows on walls – nothing of substance. The fifth was an alumnus from the class of ’96 who still lived in the area. He cancelled five minutes before our meeting, citing a vague work emergency. He didn’t offer to reschedule. I emailed Arbor to thank her for the interview and included my phone number in case she thought of anything else she wanted to share. She didn’t write back.

I spent the rest of my time dutifully transcribing the interviews, a tedious process, especially because I didn’t see anything of worth in the stories. Only Arbor’s testimony caught my imagination. I found myself rewinding and replaying it, lingering over certain phrases.

Right now, it was all I had. Her soft voice narrating the impossible. That and her sketchbook, which I found in my mailbox the next morning, nestled on top of departmental notices and flyers for campus events. She was a talented artist with a sure hand – detailed and meticulous to the point of obsession. The sketchbook started with the stained glass windows, pages and pages of them, but then Arbor had moved on to other parts of the chapel. The altar, the vaulted arches of the ceiling, the organ.

Then, the outside of the chapel and its cemetery. She had even sketched individual tombstones, rendering them in all their half-illegible decrepitude. She must have spent weeks and weeks at the chapel to draw all of this, I realized, weeks away from her studies and social ties. Weeks in a strange state of obsession, alienated from her real life.

The last few drawings focused on the crenelated belltower, then a narrow, claustrophobic set of stairs that looked more like a ladder. The final drawing was of a huge bell. Arbor must have zeroed in on the church bell. Strange, then, that she had started cleaning the windows. Why did her final sketches diverge so sharply from her cleaning activities? Something didn’t add up. It was time to visit the chapel again, I decided, stowing the sketchbook in my bag. See if I could find any evidence to corroborate Arbor’s story.

I made my way through the busy campus full of red-cheeked undergraduates clutching lattes. Brown and yellow leaves drifted down onto the sidewalks, the trees barer now than they had been only a few days ago. Late fall was turning into winter with a quickness that caught me by surprise.

Still, the day was brighter than the last time I had taken the path down to the chapel, and I felt almost excited as I left the cheerful voices behind to exchange them for the doleful calls of gulls at the edge of the cove. Light streamed into the chapel through the cracks in the roof and windows, and the stained glass cast colored shapes onto the pews and bare floors. I stood in the middle aisle for a long moment, feeling a strange peacefulness settle over me, a sense of homecoming. I dropped my satchel onto a pew and began to search along the floor for the crack that Arbor had said would be there, in the place she fell. Of course, even if it was there, I told myself, it wouldn’t prove her story was true. Anything could have caused it – a worker dropping a heavy tool, wood-devouring insects, water damage.

But my rationales were needless. The floor was smooth and undisturbed beneath the window that depicted a flying dove with a bit of green in its beak, the wooden boards well-trodden but surprisingly unmarred, not even showing signs of water damage. I felt a moment of disappointment, not because it meant that a miracle hadn’t occurred here but because I knew Arbor would be hurt by it – the lack of proof for what she’d experienced.

I decided to investigate the belltower next, the one part of the church I hadn’t been into yet. I wasn’t sure that the stairs up to the tower would be sound, but if Arbor had been up them only a year and a half ago, how rotten could they be? I climbed up to the small gallery that housed the defunct organ, its pipes glinting dully through the rust. There was a door just behind it. I opened that and immediately looked up, craning my neck and squinting to try and make out the end of the ladder in the darkness. It seemed to go on forever. My breath went tight in my throat at the thought of climbing that ladder and heaving myself up into the dark, claustrophobic space of the belltower.

How could Arbor have done it if she was afraid of heights, if it gave her vertigo? Yet she must have gone up there since she’d sketched the bell.

I stepped forward to grip the ladder, thinking to test its soundness, but the toe of my shoe caught on something. I tripped and fell forward into the ladder, having to grab on tightly to keep from falling. I banged my elbow painfully against the wood and barely muffled a swear.

I turned my phone’s flashlight on and pointed it at the floor.

“Shit,” I whispered, any hope of reverence lost.

The thing that had tripped me was the floor itself. There was a huge, splintered crack through several boards, and a dark stain spread out around it. I squatted to examine it more closely. It wasn’t just a stain from some long-ago dropped liquid. Whatever had made it was still there, dried and tacky, half-covered by dust. I ran a few trembling fingers over it, shuddering at the rough texture of the wood. The tips came away coated in a rust-colored powder. I raised them to my nose.

The smell was rotten, metallic.

It was blood.

* * *

I stumbled back down the stairs into the sanctuary, my thoughts reeling. Had Arbor fallen off the belltower ladder and gotten the story confused? If so, she had clearly lost blood. A lot of it.

I remembered something from the local historian’s blog: The burned remains of Reverend Tallow’s body had been found in exactly the same place in the original colonial church, at the bottom of the old stairs leading up to the belltower. Perhaps he had tried to take refuge up there when the flames grew too hot. But he must have fallen on the way up.

It was a strange coincidence – that Arbor and Tallow had apparently fallen in the same place. If Arbor was to be believed, then they had both died in the same place. But Tallow stayed dead, while Arbor got up and ran back to her life.

My mind was filled with horrible, graphic visions of both falls: blood and fire, broken bones and bubbling skin. Yet as I sat in a pew staring at the altar, my anxiety began to dissipate. I took a deep breath and then another. I felt calm, I realized, calmer than I had in a long time. And tired. I leaned forward, resting my head on the back of the pew in front of me. My eyes began to grow heavy. Some distant part of my brain told me to get up and leave, but I didn’t. Instead, I fell asleep.

I opened my eyes to early morning light streaming in through the holes in the stained glass and in the ceiling. My face rested on my arm and I was lying on a dusty pew, the faded red cushion musty beneath my nose. I woke the way I always did, like my body had aged fifty years overnight, every joint stiff. I stretched as much as I could before sitting up and blinking at the chapel around me. Dust motes shone in the pale golden air; ivy crawled in through the windows. Birds’ nests dripped straw from every rafter.

It was beautiful. Beautiful in its disarray, in its decomposing. I hadn’t thought destruction was capable of beauty, but slow destruction – the slow unmaking of human effort through nature’s inexorable means? It took my breath.

The place felt hushed and… holy. Holier than any polished, perfect cathedral. A place apart. It felt like somewhere one would find at the end of a journey, the keeping place of the Holy Grail. Maybe everything I sought was here, I thought. All the answers to my questions, my doubts. Maybe this was the place that could help my future make sense again.

But beneath these thoughts rose another, unwelcome one: I had done exactly what Arbor warned me not to do. I had spent the night. I grabbed my bag and Arbor’s sketchbook and hurried out, superstitiously afraid of looking at anything else in the chapel.

After cleaning up in my loaned dorm room in freshman housing, I hurried to the library, to my usual carrel by the window. As I slid into the hard, wooden chair, I felt my mind clear and my academic training take over. I had researched the general history of the chapel, but hadn’t yet dug deep into Samuel Tallow – a necessary research point considering the manner of his death. A quick search of the library’s online catalog revealed a small collection which included Tallow’s papers and a diary containing notes for sermons, descriptions of life events, and personal reflections. It was being held in a special archive here on campus.

I emailed the special collections librarian to request access and received a swift and enthusiastic response. Apparently there weren’t too many people on campus interested in eighteenth-century Anglican ministers. An hour later, I was sitting in a small room with the journal on the desk before me. It was written in a tight, slanting cursive that the middle-aged, cardigan-clad librarian offered to decipher for me if I needed help.

“Why didn’t these burn in the church?” I asked him.

“Most of his papers did. But this journal was left on his bedside table in the parsonage. Luckily for us,” he added as he ducked out of the room.

Left alone with Tallow’s diary, I took a deep breath and opened it, half-afraid of what I might find. Unlike the chapel, Tallow’s journal had been well preserved, the ink still dark and clear. Once I got used to his handwriting and archaic diction, I sank into Tallow’s mind. It was not a pleasant experience. He seemed hounded and harried, both by his role as an Anglican minister in a Puritan land on the cusp of revolution and by something more personal, a shadow always at the back of his mind. His sermons were stern and steely, his admonishments to himself even more so – pushing himself to breaking when he was ill, condemning himself for every human emotion and desire. I found myself looking for softness, sweetness, even a hint of it, but it wasn’t there. This was exactly the kind of man who would let himself burn with his church.

But was he the kind of man who stayed behind to haunt it hundreds of years later? I wondered, feeling less scholarly than I had in my entire academic career.

And if it was Tallow haunting the chapel, where had he found the compassion to breathe life back into the tiny body of a sparrow, sending it flying back to its life? When had he learned the mercy that let Arbor up off that wooden floor, to draw and paint and maybe one day to forget St. Clement’s Chapel’s dark corners? I didn’t see any of that here in his journal. Only hardness, an unyielding spirit, a sense of conviction that felt like being strangled.

Was his haunting his redemption, his ghostly miracles a belated absolution?

Or was he simply reenacting his own dark end?

I studied the journal until the library closed, returning it to the front desk resignedly. My body ached from the hours of sitting on a hard chair. I walked out of the library into the cool moonlight, into a cold autumn breeze that sent brown leaves skittering eerily down the path before me. I decided to take a walk before finding something to eat, just to loosen up the ache in my spine. I told myself I had no particular destination in mind, but I knew where I was going.

The chapel loomed up out of the darkness, a gray giant in the encroaching fog that was rolling in with the tide, carrying the smell of salt and fish.

“Lana!” a voice called from somewhere close by.

I startled and turned. I squinted into the darkness, but I could only make out a general human shape, accompanied by the smell of cigarette smoke. “Sorry, who’s there?”

“I’ve been trying to reach you all day,” the voice said, worried-sounding. Arbor stepped into view, a lit cigarette in one shaking hand. “You shouldn’t be here. It’s not safe.”

“I’m fine,” I said, both pleased and annoyed that she had taken the trouble to track me down. “My phone must have died, and I’ve been busy. I found Tallow’s diary in the library. I’m just here to do some re—”

“You’re not,” Arbor interrupted, coming toward me fast. “You’re under its spell.” Up close, I could see she was terrified. The hand that held the cigarette trembled. Her eyes were wide, pupils blown. She cast nervous glances at the chapel. “Come home with me; you can stay at my place until you feel like yourself again.”

I stared at her for a long moment, my thoughts syrupy slow. I could imagine a whole life unraveling from this moment if I did what she asked. Maybe we would sleep together, maybe we would fall in love. Maybe I’d give up on my degree, on being a priest. Maybe we’d work silly, underpaid jobs and get a cat. We’d listen to records and share our favorite books and drink cheap wine. We would be happy, at least for a while.

I looked away from her frightened, lovely eyes, back toward the waiting chapel. “Thanks, Arbor. I really appreciate your concern,” I said, forcing a smile onto my lips. “But I’ll be fine, I promise.”

When I started toward the chapel, she called my name a few times, but she didn’t follow me or try to stop me. I slipped inside like a shadow, feeling as if I was coming home after a long trip away, back to a place where I could shed my outer skin, be the vulnerable creature underneath, forgetful of myself, existing in that automatic way which requires no thought, almost no self at all. Home.

The chapel’s interior was cool and damp with the rising fog, wreathed in quiet. I sank down into a pew near the altar, feeling bodiless, diffuse, as empty as the salt air and fog and the borderless night.

* * *

I came awake suddenly and completely, a beam of moonlight falling directly into my eyes. The moon was high up over the chapel, and the fog from earlier had dissipated, leaving a cool, clear black sky full of pinprick stars. I stared up at it for a long moment, trying to figure out what had woken me.

Smoke. I smelled smoke.

Suddenly, the room that had been still and quiet, held in moonlight as if in a cupped hand, was aflame. Fire danced up the walls of the chapel, smoke rolled to the rafters. I ran for the front doors, but they were barred and already engulfed in flames. Blind in the dark, my lungs filling with smoke, I ran instinctively for the door that would take me up, out of the flames and the burning smoke. Up the stairs and past the organ, to the ladder that led to the belltower. I put my foot on the ladder, grasped the highest rung I could reach, and hauled myself up into the dark.

I seemed to climb for a long, long time, the narrow walls of the shaft so near I bumped my elbows against the bricks. My breath was tight in my chest, my heart beating so hard it was all I could hear. The fire seemed far away, as if it were happening somewhere else.

Finally, I reached the top of the ladder and pulled myself up into the small space of the belltower. Above me hung a huge bronze bell, beautifully carved and a murky blackish-green in color. It hadn’t been updated with a modern carillon, which meant it must be rung by hand. Without thinking I reached forward and yanked the bell pull, exerting all my strength to ring it. Maybe someone down below would hear it and send help before the entire chapel burned to the ground with me inside. Maybe Arbor was still down there, trying to save me.

The sound rang out, erratic, weaker than I’d hoped, but surely still loud enough to reach the campus. I kept ringing the bell, the reverberation of each strike running all the way up my arms, making my teeth ache. I lost all sense of myself, the distance between me and the walls of the church disappearing, until I was not a person ringing a bell but the sound of its ringing, the smell of damp stone walls and rotting wood, my beams stretching up up up to the heavens, becoming sanctuary.

The weight of the bell pull had me now, its momentum carrying me forward and back, forward and back, with each deep resonant peal. But never well-coordinated, I lost my footing on the return pull and was thrown backward, my aching hands losing hold of the rope. In that instant, I was myself again, returned to my imperfect, lonely body. I stumbled. Back and then back again.

My foot reached for solid ground and found only open air.

UTILITIES

Genevieve Cogman

The cracked chimes of the campus clock striking midnight vibrated in the still air of the room; they stirred the dust which topped the bookcases and lay along the skirting boards, and made the Stolas utility perched on her desk twitch his wings in annoyance.

Madeleine looked up from her work at the sound, irritated. She hadn’t thought it was that late. A lecture in half an hour, and she still had two utilities to code for the next night’s classes, and if she had to stay in afterwards to finish her work then she’d never get to go out partying with her friends in realspace. With a gesture which had carried over from her actual body to her digital avatar, she ran her hand through her hair in annoyance. Time, time, there was never enough time…

And then the clock struck a thirteenth note. The sound seemed to swell in the air like ripples. Several of the books on Madeleine’s desk closed themselves, flipping shut with little slams and puffs of dust, and the Stolas utility whipped his head completely round, hooting in disapproval like the owl he resembled. Nobody had yet achieved true artificial intelligence, but good coding could make a utility seem sentient – or at least, sentient enough to interact with the world around them. It was more comfortable for their users that way.

“Oh, do shut up,” Madeleine murmured, though whether to the school clock or to the utility wasn’t quite clear. Pointless as the gesture was in virtual reality, she rubbed her eyes and took a deep breath.

Apparently, the universe wanted to conspire against her and spoil her fun. Well, fine. She’d just have to conquer the world and make everyone pay and force them to let her sleep in late. That’d show them.

Or possibly she was just a little data-happy from spending too many hours logged in. That could happen. It was something every student was warned about – and then ignored. There just weren’t enough hours in the day.

Though why had the school clock struck thirteen?

With a shrug, she decided it must have been a glitch in the virtual reality. Such things were common in less well-built virtual spaces; it was plausible that even the Scholomanz, one of the world’s best universities, might occasionally blink. It would probably go down as a university legend, something which was cited to freshmen as “the only time we’ve ever had any issues here in the last decade…”

She snapped her fingers, rising from her chair.

Nothing happened for a moment – and then the Stolas utility spread its wings and floated into the air, landing on her shoulder. Tiny claws pricked through her blouse and into her skin, the momentary pain and fractional drops of blood a virtual token of the improved connection as its library function flickered behind her eyes. She reviewed half a dozen possible utilities – Crocell for rapid diagram formulation, Dantalion for instant messaging, Sitri for scanning other people’s avatars – but decided that the lecture didn’t warrant anything that serious. Some of her fellow students liked to go around the Scholomanz so hung with utilities that their avatars could barely string two words together when you spoke to them in person, but Madeleine had always felt it was safer to make do with the minimum, and only call up what you actually needed.

And at this end of term, it was important to be safe.

Of course, that didn’t mean she couldn’t enjoy designing and coding the utilities. Making a tool which performed its function efficiently was a matter of competence. Making one which did so with elegance and style, and which anybody could see was her work – well, that was a matter of pride, and one could hardly say there was anything wrong about justified pride…

Yet all the pride in the world would be no help to her if she wasn’t on time for her lecture. She took the stairs two at a time, the flowing panels of her scholar’s gown rippling dramatically behind her as she pivoted around the banister and came stampeding down to the ground floor. (Perhaps the gown, deliberately coded to always flare properly and with maximum impact, was a luxury – but everyone deserved one luxury, didn’t they?) She otherwise looked much like her physical self these days; she’d long since gone past the stage that everyone went through when they coded up their avatar with implausible eyes, hair, bulges, and other details. Pupils at the Scholomanz didn’t have the spare time or energy to maintain that sort of indulgence. Their brains were required elsewhere.

Andrew was waiting for her at the foot of the stairs. His Dantalion hovered by his ear, barely three inches tall, its tiny book open in its virtual hands as its multiple faces whispered email updates into Andrew’s ear. Andrew silenced it with a gesture as Madeleine joined him, giving her a thin-lipped smile. “Getting better. We might actually be able to walk to the lecture rather than having to run or teleport.”