Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

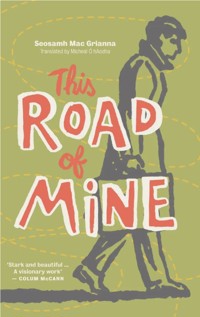

First published in Irish by An Gúm in 1965, the magnificent autobiographical novel by Seosamh Mac Grianna Mo Bhealach Féin is translated here for the first time into English by Mícheál Ó hAodha. With notes of Dead as Doornails and The Ginger Man in its absurd comedy, Seosamh Mac Grianna pens his reaction to an anglicised, urbanised, post-revolution Ireland, demonstrating his talents at their peak. This Road of Mine relates a humorous, picaresque journey through Wales en route for Scotland, an Irish counterpart to Three Men in a Boat with a twist of Down and Out in Paris and London. The protagonist follows his impulses, getting into various absurd situations: being caught on the Irish Sea in a stolen rowboat in a storm; feeling guilt and terror in the misplaced certainty that he had killed the likeable son of his landlady with a punch while fleeing the rent; sleeping outdoors in the rain and rejecting all aid on his journey. What lies behind his misanthropy is a reverence for beauty and art and a disgust that the world doesn't share his view, concerning itself instead with greed and pettiness. The prose is full of personality, and Ó hAodha has proved himself adept at capturing the life and spark of the writer's style. His full-spirited translation has given the English-reading world access to this charming and relentlessly entertaining bohemian poet, full of irrepressible energy for bringing trouble on himself. As well as the undoubted importance of this text culturally, Mac Grianna is able to make rank misanthropy enjoyable – making music out of misery. The voice is wonderful: hyperbolic but sincere.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 334

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

DUBLIN

Foreword

A hundred years ago Seosamh Mac Grianna (1900–90) was beginning his journey as a writer. Little bits and pieces of fiction and journalism in Irish were beginning to appear in print around the 1920s. Born in 1900 in Rann na Feirste, part of the Donegal Gaeltacht, Mac Grianna could not have imagined that a century later his work would still be read in Irish and, indeed, in translation in English. His active writing career was far too brief: fifteen years or so, from his early twenties until his mid-thirties. Ill health dogged him often through his days and he spent many long decades under care – his pen set aside.

Yet here we are, the fistful of books that he wrote and his journalism still attracting readers. The quality of what he created has trumped all: war, illness, anger, neglect and personal tragedy. There is a lesson there, perhaps, for all writers of Irish – indeed for all writers who do not work in English, who work in native languages, smaller languages, ancient set-aside languages, can still be rewarded with a dedicated readership; that original books can still cast a spell through the long decades; that imaginative, intelligent and thoughtful writing finds its place on book shelves and in the hearts and minds of loving readers.

Mac Grianna was a remarkable man and lived in remarkable times. He was born in Donegal at a time when the cataclysm of the Great Famine was still in living memory. His Donegal was part of a united Ireland, under the British Crown, at a time when the sun did not set on the British Empire. He saw the outbreak of the Great War and was tempted to join the British army but the Easter Rising set him on a different course. He saw the War of Independence and the Civil War that followed andchosethe Republican – and losing – side. He saw partition draw a scar across Ulster and he saw native governments in Dublin try to give Irish an honoured place in a new, truncated Ireland.

He wrote during it all. There is no doubt that the times in which he lived informed the literature he produced. He knew the traditional lore of his townland and respected it, but often found his fiction in contemporary Ireland and its politics. In this, he was undoubtedly influenced by the writing and journalism of both Pádraic Ó Conaire (1882–1928) and Patrick Pearse (1879–1916).

The Irish language was his medium; the poor benighted, ignored, miraculous, mysterious Irish that was (and is) the community language of Rann na Feirste and much of Donegal even then. It was, and is still, a language of no commercial value; English was, and remains, the language of the powerful and influential. Irish is the echo of other times: of wars, conquest and famine, of events and of people who are not to be discussed in polite society. It was the language of the poor, of the most marginal and disdained.

Mac Grianna, however, found his voice and vision in the Irish language and embraced it. Irish was the harder choice for him, a language that places the writer into a very small circle of readers – and not that many native speakers could even read Irish in Mac Grianna’s youth.

Still, itisan ancient language. That much is true. The writer of Irish may not enjoy the cachet of the English-language writer but, in these days ofA Game of Thrones, the writer of Irish can, legitimately, point to legends in Irish that are every bit as fantastical, and brutal, as anything imagined by George R. R. Martin. The writer of Irish steps into a stream that stretches back thousands of years. Even in contemporary Ireland, a place that exists it seems only to buy and sell things, there are living Gaeltacht regions in all four provinces, battered and bruised, constantly under threat and endangered, but there nonetheless.

These Gaeltacht areas, like a shee fort, open up another Ireland and another Europe. These Gaeltacht regions light the way to Scotland, the Isle of Man, Wales, Cornwall and Brittany, to other linguistic realms that hint at a forgotten Europe and remind us of a different cultural past. Mac Grianna’s journey took him to Wales and their Welsh language, a sister language to his own. There is curiosity in his travels around that land and a little envy perhaps that Welsh had seemed to survive in a way in which Irish had not. That country inspired one of his best books,Mo BhealachFéin– a memoir and meditation.

Here we are then: still reading Mac Grianna’s books a hundred years after he began his literary journey – in English however, a language he did not want to write in but a language whose naked power he understood. He translated much from English into Irish in an effort to earn much needed money. He knew the importance of the translator’s role of turning the unfamiliar into the familiar, of presenting good literature to new readers.

Mac Grianna noted once that the poet’s journey was a lonely one. It is, but you do meet friends on the way. I think he would be glad that a writer of conscience and creativity like Mícheál Ó hAodha has taken on this task on his behalf. Yes, I think he would have been pleased to know that another writer graced him with his care and attention and that his literary journey continues into another century, in another way.

Pól Ó Muirí, author ofSeosamh Mac Grianna: Míreanna Saoil(2007)

Lá Fhéile Muire san Fhómhar, 2020

1

They say the truth is bitter, but believe me it’s harsh and this is why people avoid it.

It was early in my life that I saw it stretched out in front of me, the road of my heart’s desire, the winding path skirted by peaks more beautiful than any hills found in music and the breath of wind above more perfect than any earthly breeze – as wine vanquishes water; the old bridge that listens to the whispering stream for as long as first, fleeting memories linger; and whitewashed villages set between the early noon and the mouth of the dawn; and sheltered nooks quiet and peaceful where one rests and comes to know every living sprig and herb, the scattered roses made of dreams:

Ar bhruach na toinne le taobh na Finne

’S mé ’féachaint loingis ar sáile.

On the edge of the wave beside the Finn

As I looked on ships upon the sea.

The way of no return, that inconstant road between care and fear. Who’ll tell me that I never walked it – me, the king of Gaelic poets in this, the twentieth century, the era of Revival? Who’ll tell me that I was guided by the words of casual friends most days since I was born? And even if I was always slow to let them guide me, I still found myself halfway between admiration and contempt. You’d need patience with the likes of me, and I’ll tell you now why. And I’m afraid they still won’t understand even when I give them the truth straight.

But then, what’s the point of me writing this here book if I am to remain misunderstood? And so I’ll tell you now why I didn’t keep my distance from these casual friends of mine the most of my days, and why I didn’t take the path of joy and enchanted wandering as I should have; it’s a long time now since I abandoned the armour that most other men sport – a steady job and opinions that stand to you and ensure you fit in with the crowd. Bad as I was, I never had any time for all of that. But then I also had a deep and powerful fear of myself. No wonder – when you think that my own crowd were always down on me as if there was a danger in me that the world could never see. And it was always like this: when someone else caught a cold, they felt sorry for them; if I got one, it was something to be ashamed of however. If someone else got angry, they were alright because they knew how to control themselves; but if I got angry, I was a wild bull of a man. If someone else did something untoward, it was quickly forgotten and they got away with it; but if I did something wrong, I never heard the end of it. I don’t like this type of Christianity, if Christianity it is – but there’s a lot of it in this world. Maybe I had a power in me that I didn’t understand; maybe I still don’t understand it. Is it any wonder that I felt myself tied up in a thousand knots before I’d done anything at all, I ask you? I rebelled. I broke out of schools and colleges. In1916, I left Saint Eunan’s with the intention of joining the British Army but Easter Week put an end to that. I disappeared from other colleges too and yet, despite it all, I reached the age of twenty-one and I had qualified as a schoolteacher. If it wasn’t that I had some bit of guidance from others, if it wasn’t that I had a right fear of myself, the truth is that I’d have had no education at all. They didn’t understand what drove me deep down and even if they tried to give me the odd bit of guidance, it was only very rarely. I knew early on that they were trying to break my spirit in reality, and so I was rash and uncontrollable as a consequence. I was wary of others. I also wrote stories that might never have seen print if it wasn’t for others. Because I’ve never believed that the poet should prostitute his art. Once my writing became known and others understood I had that gift which was very rare in the Ireland of my day – the gift of poetry – I think they expected me to share my store with them. I refused however. They couldn’t get a word out of me. I never revealed what was really on my mind. I protected my inner soul. People close to me claimed that I was lazy and yet the same people saw me working, and working harder than any man at times. They tried to pin me down and box me in but they could never manage it. I had too many sides to me. That’s my gift. And eventually they let me be, even if they – my casual friends that is – kept inviting me around to their houses for longer than I’d hoped. In the end, they left me alone. It was painful at first but I got used to it. Because I always wanted to be alone. There were people close to me that I had a great respect for needless to say – in so far as they understood. But I could tell that they wanted too much from me and even if I’d shared my gifts with them from morning till night and week on week, they’d never have been satisfied. Maybe I made them jealous or greedy.

Maybe I didn’t understand then what I do now – that it’s in our nature to steal the wealth – one man from the next. I hope I never hurt anyone. To put twenty words into one, for the guts of ten years I tried to make a living the same as anyone else, even if any blind man born could tell that I wasn’t like the others. I was afraid back then that if I found myself in trouble no one would help me out. And it’s in my nature that I couldn’t care less about anyone else. A searing honesty and courage is what lies behind this view of the world. I always knew – because I’ve got a wise head on me – that honesty is very difficult if you’re too poor for it and the same goes for courage also. You can make the most of your gifts if you have a bit of material comfort. But because I didn’t give a damn about humanity, I found myself on the margins. Still, my imagination and art were well served by this isolation seeing as I was free of the pollution of the mind that characterizes contact with others. Life has a grip on every man born in one essential aspect however. People may differ from one another but they all have an appetite and I had an appetite as good as the next man. I had to keep my belly full. I had to earn my bread somehow; and the wheat can’t grow by itself.

I won’t bother here now with the nine schools I taught in across the nine counties of Ireland. Or the fact that I gave up teaching in the end when I had a dream that the whole world was bound tight with ropes – up, down and across – like the lines in a school roll-book. I couldn’t suffer the world any longer and it embroidered this way. The second job I had was translating books into Irish. The government was running a scheme for the publication of Irish-language books and I began working on this. Not that the government of the day was known for its promotion of poetry or art. And the truth is, neither I nor the others were too taken with An Gúm1from the beginning either – other than making jokes about it, that is. It came looking for me and gave me books to translate. An Gúm had a welcome for everyone back then, or until it had enough books published to keep it up and running. But then the publisher became difficult and it was afraid that people might earn big money from it. We won’t bother with that for the moment however. The way I saw it – it was willing to pay me for work that was as easy as tying your shoelaces, so that I didn’t give a damn what the place was called really or what stupidity it got up to either.

I wasn’t long working there however when I discovered that this business was no game – not at all. I was working with literature the same way another man cuts timber or collects sawdust. An Gúm were the harshest people on writing I’ve ever come across and even if six or seven of the greatest poets that ever lived came back and worked for them, they couldn’t have been harsher or more strict on them. There were others working there also whose company I often found myself keeping. But it was just my luck that any time we met up the sole topic of conversation was An Gúm. It was bad enough working in the place but to be talking about it all the time as well! I’d run into people I knew every now and then out on the street and they’d ask me: ‘Are you still translating the books into Irish?’ That was a real punch in the gut for me, you can be sure, the likes of me who’d proved that I could write real poetry! I hated An Gúm and it was this same hatred that kept the few small embers in my soul aflame – until it came time for the reckoning. I always hoped to destroy An Gúm somehow and I couldn’t have cared less about the consequences for myself either. This is not to say that there weren’t some advantages to working there of course. I didn’t have to get up too early in the mornings or rush around the place like everyone else. And I got my wages in a lump sum and enjoyed spending it too. But then I was tied down in other ways also. I never trusted the civil servants in the system fully. I took the advice of my casual friends and didn’t get above my station either – by earning more money than others or by making waves at work. I watched and learned how the world works quietly and in my own way instead. And I loved the freedom of working there even if I was tied down by certain rules and regulations in other ways also. It was still much better than the slave whose every hour is subject to the clock.

I was four years working there when the government changed. This was likely the moment of reckoning, I said to myself. It was just after New Year in1932. A few of us did whatever we could to find out what the future held for us there. People went and spoke to the newly appointed Minister. Articles appeared inAn Phoblacht2criticizing An Gúm in case what was being done ‘through the official channels’ wasn’t enough. We did our best – or as best we could – given the circumstances. I was happy to continue working there as things stood. But the others wouldn’t listen to me. We weren’t all pulling together, not at all. I have my suspicions that one man was trying to get a job in An Gúm while another was afraid of his life that he’d be kept on, and a few others didn’t care one way or the other, and there was me just left on my own really.

The story I had in with the publisher– An Droma Mór3– was different from the usual stuff they published. And there was no way I’d give them the satisfaction of rejecting it, I told myself. So I went down to the office one day and took the book away again with me. Maybe they’d never seen someone angry in that office before, but they saw me raging that day, that’s for sure. I don’t remember everything I said to them but anyway I asked for the manuscript back and was forced to grab the man who had it by the scruff of the neck and half-throttle him in the end. And I was delighted that I did this too. Because if I’d spent much longer in An Gúm translating books to Irish, I wouldn’t have had a spark of creativity left in me. Sure, I’d have had a way of making a living alright but I’d have been like someone who’d neither won nor lost – just a boring machine, an automaton. I lost out on the cushy number, cursed though it was, but at least I was free to go my own road. And it’s not as if I passed the rest of my days without tasting the better nectar of life either. I put myself in harm’s way and even in mortal danger many a time – ever since that afternoon when I jumped into seven feet of water on a remote beach without a safety ring, and I just ten years of age. When the fighting broke out in1920I was involved in it to a certain extent. I didn’t understand what it was all about of course – but that’s another story. Because, in truth, we in the Donegal Gaeltacht were never completely colonized. As far back as1602, Rory O’Donnell had destroyed his pursuers at Cornaslieve and Beltra after the Battle of Kinsale and the English made peace with him. If he’d been beaten, he’d have been put to death. We still have most of the noble families in the Donegal Gaeltacht to this day, something that can’t be said about any other Gaeltacht. And I know that the Brehon Laws are still followed on strictures relating to the raising of sheep in my native parish even today. So, I spent a while in prison for a cause that I hadn’t the slightest interest in really. This taught me a bit about life even if it numbed my emotions and creativity in many other ways as well. The likes of us are as strangers amongst the anglicized Irish. Reflecting on this now, various notions come to mind: how we were forbidden as children from calling a woman a fool – or saying that someone was ugly or a liar. We received the education of the nobility especially in Aileach,4the place where the Gaels held most power in ancient times. The most wonderful thing of all is how the racehorse is better beneath the plough than the heavy nag. Even if our people are quieter and more even-tempered, this doesn’t mean that they don’t do Trojan work and suffer hardship that would break people anywhere else. We can’t avoid the truth however and we must suffer it. Seeing as I’ve brought the discussion around to it, I too have survived many hardships over the years and benefited by them also. I wasn’t following my own road fully when I endured them however. What I would really love to do is turn the world upside-down so that there was magic in every living thing even if it was only scratching yourself. Indeed, I’d say that you’re probably not allowed scratch yourself anymore the way things are these days. But says I to myself: Hey An Gúm! I’m off to follow my own road now and without your permission either!

2

Iwas staying in quite a big lodging house at this time. It was a busy place with lots of people coming and going including newspaper-men and couples from the country who’d got married in the city; there were lots of them there. I met people from all over – from Norway to Australia. Funnily enough, the most interesting character of the lot was the woman who ran the lodgings itself. She had Jewish blood, I think, and she was dark and had an unusual swarthy look about her that would have put you in mind of a city when the night is over. Although she was middle-aged she used to plaster herself in make-up as if all she had in mind was hunting men. She was married to a decent and very polite man whom she’d cursed with bad luck by all accounts. She was hard-working, worldly and greedy and, that said, she was a poet.

In hindsight, I can see now that my stint in that lodgings was as nice as it was in any of the twenty-five lodging housesI stayed in from my first arrival in Dublin. I had a small room upstairs at the very top of the house, four floors up, and I did my writing in the sitting room at the window, looking out at the park across the way. This sitting room was crowded with people sometimes, especially at night, when I sat there writing and between every second sentence I’d listen in on the chat going on around the fire.

The lodging-house woman had a son of whom it would be untrue to say that he was his father’s son in any way – a man who was as fascinating as herself. He was a big, heavy lad whose black hair was streaked with grey. They regularly made out that he was only twenty-two but he looked at least thirty-five, if he was a day. He had a religious mania as strong as I’ve seen in any man and all he ever talked about was religion. He was a teacher but he wanted to leave his job and join one of the religious orders. He’d arrive into the room eager for a chat every afternoon and before I knew it we’d be debating everything religious. He had a whole host of stories about the bodies of saints that had remained uncorrupted for hundreds of years, stories that I didn’t believe at all. These weren’t the type of stories that I’d heard tell of growing up in the Gaeltacht at all and it often got me thinking that the Catholic faith in the Gaeltacht and in the areas outside it was very different. I can’t remember many of our conversations now but one image that remains clear in my mind is the sight of this man’s dark, fleshy face and his grey-flecked hair and the tormented soul that was him. And his mother told me herself that he was always keen on joining one of the religious orders but that it’d break her heart if he did. She’d lost a son already in the Great War of1914. There was no question but that she and the son were mad about each other; there was just them in the world. Her daughter was always cleaning and cooking from morning till night and her husband spent all his time down in the kitchen, and to tell you the truth I don’t know whether he was washing dishes or what he was doing. Any time she left the house for a walk, it was the son who went with her and whenever she went to the pictures he was with her too. He went with her the same whenever she went on holidays. They were the gentry of the family – no doubt about it.

This woman often called in to me for a chat about her son and the poetry that she wrote. She regularly gave me newspapers – the local ones – to read also. There’s a ‘poet’s corner’ in these newspapers and not a week went by that this woman’s compositions weren’t in the newspaper. She’d been living in the district that this newspaper covered before she’d first come to live in Dublin city.

There are many different schools of poetry in the English language, but I don’t know of one that would describe this woman’s work. Her poems were a little bit similar to those of Mrs Hemans, the ones we’d had in our schoolbooks long ago. I’m not sure whether I can give the reader a flavour of her writing but this translation may give you a sense of it:

You were with me on my journey each day,

For many long years you were my love;

Many is the tale that you heard

If only you could tell them again today

When I was young and you by my side

I was not without pride and my heart was not heavy;

I used to walk the road to the town,

Everybody said I’d a sweet way about me.

But old age came in the same way as night falls,

And it left both me and you lamenting;

You are worn out now, without value or beauty–

My little old satin bag I myself had.

She thought that the ending to the poem was very clever and that everyone assumed that she was lamenting a lover or a friend up to that point. She told me about stories that she wanted to write one day if only she had the opportunity. She had some sort of a love story about people living in a castle in France but if I was to be hanged now I can’t remember it. She said she had another story that would amaze the world if she wrote it. She’d never write it however in case it put someone in mind of committing a terrible deed. This was a story about a woman who hated her husband so much that she wanted him dead. The woman began giving him damp shirts regularly until he fell sick and died. But there wasn’t a law in the world that could prove she’d killed him. She was afraid some woman might do something similar if she wrote the book. But what I was afraid of – in my own mind – was that she might do it herself to her own husband seeing as she detested him so much. I stayed in that lodgings for the winter and many people came and went during that time. I had a visit up at the top of the house one day that was different from most however. A messenger came to me from the firmament just as I was going to sleep one night. I was looking deep into my own soul when a dove appeared and stood on my windowsill. It was like a messenger from another world, a world vast and boundless, and hidden from us, a perilous realm that sought to draw you in – like beautiful music far away in the enchanted fairy sphere. If you spotted a dove sitting on your windowsill in a lit-up room very late at night you’d know what I mean. You couldn’t but take note of its eyes, feral and untamed, its striking plumage; and you too would feel the living tremble of its tiny body. You wouldn’t have paid any heed to this same bird if you’d spotted it out in a field or on a background framed by leaves – but all that was here now was a tiny room, bare and empty except for a bed, a press, and one small cheap picture – and a wall plastered in paper – the most unnatural sight that man ever created. But in that moment, my little room, shabby yet cosy, was extinguished as if in a flash of light or torn apart by a great gust of sea-wind. And I saw a thousand leagues of sky in that dove’s eyes and a thousand enclosed cities and eddying rock-pools beneath me, and I was king of eternal wind and sky.

Whether it was by nature or education, my first instinct was to try and catch that dove somehow. This was when that room turned small and narrow however, so narrow that the poor dove panicked and flew crazily all over the place and it would have killed itself only that I managed to get the window open. It shot out across the street in three flaps of its wings and came to rest on a tree opposite. That winged dart of his – as noble and magnificent as a wave – has remained with me ever since, as mournful as a wound.

The people of the house told me the history of that dove later. It had belonged to an army captain who’d lodged there at one time. They asked me whether I’d noticed the ring on its leg and sure enough, it had sported a ring alright. The captain had moved from that lodgings eventually and he had left that part of his life behind – whether it was that he’d got married or had died or been imprisoned, or whether he’d just gone to live somewhere else, I don’t know. But his dove had returned there every now and then, visiting that top window as if to pay tribute to the old captain.

This was my way too, I thought, this same wild appearance and retreat. I too would love to have disappeared through the top window the same as the dove, particularly seeing as I owed ten pounds in rent. I’m as honest a man as walks the Western world, I think, but when it comes to money, it’s not much of a crime to leave a lodging-house woman ten pounds short when you’ve paid her a year’s rent. Anyway, I didn’t have the ten pounds to give her and there’s no law for necessity. I began to pack my bits and pieces together carefully one day and made ready to escape. If you think for one minute however that this woman didn’t sense what I was up to, then you’re asleep in this world! Like the dog who gets the scent of the rabbit, she was onto me immediately and knew that I was up to something. Once I’d my bag packed, I went down to dinner and she was over to me straight away.

‘Mac Grianna,’ she says, ‘I’m waiting on that ten pounds from you. I’ve bills to pay you know.’

‘My good woman,’ I says, ‘I know exactly what you mean. Shur, we all have bills to pay but as the good Prayer says: “Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.” As I gently informed you previously, I don’t get paid by the week and I’ve to wait a good while sometimes before my money comes through. You gave me leeway on paying my debts before and I’m sure you’ll do it again.’

‘That’s alright,’ she says, ‘but you should know that it doesn’t suit me to keep lodgers that don’t pay me every week. I’ve a lot of expenses on this house. I’ll expect that money from you come the end of the week.’

‘Alright,’ I says. ‘You’ll have it by the end of the week even if I’ve to sell the shirt off my back. Don’t worry love. I won’t let you down. I know you’ve enough things to be worrying about as it is never mind getting paid on time.’

I saw her off from the door of my room but only just about. She spent the rest of the day sniffing around. I went into the sitting room and hunched over a book and you wouldn’t have known (unless you were the lodgings-woman, that is) that I planned on running – no more than the leaving of Carraig Dun.1

The next day I waited until I saw her leaving the house all dressed up. Rather than leave it too late, you better go for it now, I says to myself and I ran upstairs, as alert and quick as the cat pursuing the bird. Back in the room, I realized that I hadn’t packed my bag right at all and that I’d left out the most important things. I pulled the bag open and threw in whatever I could. But like all the bags of the world, I couldn’t get it to close for me there and then. This was bad enough but I couldn’t even curse the bloody thing rightly while I was at it! I gave it one mighty push and eventually managed to get it closed, then stuck my head outside the door. The house was so quiet that I heard myself tremble and it felt as if a full hour passed before I negotiated the first flight of stairs and scanned the doors below – it felt so long. And if the sun outside hadn’t told me otherwise, I’d have a sworn a week went by before I reached the ground floor. I was just a few steps from the front door when the sitting room door opened and who appeared all of a sudden but herself! And there was me thinking that the boss-woman must be a least a mile away by then! Who’ll deny that lodgings-women have magic powers all of their own?

‘Hey! Hey!’ she says and she rightly wound-up! ‘You’re not leaving until I get what I’m owed!’

‘Hang on! Hang on!’ I says. ‘I don’t owe you anything and don’t think you’re going to stop me leaving either! No man will stand in my way, I swear,’ I says, trying to push past her.

‘Hey, Cyril!’ she says. ‘Hey, Cyril!’

And where was the son but right outside the front door ready to block my escape. He put his hand on the glass of the front door and pushed his way in, then grabbed a hold of my bag. In that instant, and as clear as day I saw them – every tasteless drop of tea and every miserly slice of bread and every pretence of a dinner I’d ever had – in all twenty-five lodging houses – they flashed through my mind all at once. All the suffering and loneliness of those places rose up inside me like one powerful wave and I clocked that righteous, grey-streaked buck with an almighty punch. I hit him so hard that I thought I’d broken all the bones in my hand and he crumpled onto the ground as if he’d been pole-axed stone-dead. I jumped out the door and made a run for it. I went around the corner at the top of the road and kept running and if I was followed, I didn’t see anyone. Then I slowed to a walk. I wasn’t long convincing myself that I’d killed that man however and that I’d left him dead on the side of the road behind me and that I was in deep trouble. I was sure too that guilt was written all over my face and that anyone who passed by could see it clear as day. And I was sure that people were avoiding my gaze, it was so obvious. At one stage, I spotted a big, tough-looking guard across the street and I was sure that he’d recognized me and so I slipped around the corner as fast as a weasel through a ditch.

I wasn’t stupid of course and I knew that they couldn’t hang me for punching your man back there but seeing as I was on the run, I was as well letting on to myself that I’d killed a man and that the human race were bent on revenge and pursuing me for justice. Suddenly, as if from nowhere, a lodging house appeared ahead on the road and it reminded me – despite my best intentions – that I’d just killed someone. It had the look of a place that a killer might hide out in. It was off the beaten track and looked as if no one ever stayed there and even if I was fairly well-up on all the streets in that part of the city – so much so that I knew half of the people around there to see – I’d never noticed this lodgings before. The name of the place was written above the door in big brass letters, half-broken and missing, so that one could say with absolute truth that it was a house without a name. I went in. A sullen, dark-looking girl appeared after a few minutes from somewhere in the back and I asked for lodgings. She handed me an old ledger to write my name in, a ledger so ancient looking that you’d have sworn no one had written in it since the Book of Promises. In for a penny, in for a pound, I thought and signed myself in as ‘Cathal Mac Giolla Ghunna’ [Charles McElgun].2I’d convinced myself by then that there was a dead man after me for sure.

I spent that evening sitting in a big, wide room made of a poor light and a terrible loneliness. No one came in or out except for two or three people who looked like university students. They sat themselves over on the far side of the room so that they might as well have been a quarter of a mile away as far as I was concerned. I glanced over at them the odd time thinking: if you only knew the terrible deed I’ve just committed! And sure enough, it wasn’t long before I could tell they’d marked me down as a bit odd, and so I hid my face from them as best I could. I tried to put together a plan then on how best to evade the enemy in pursuit, but couldn’t think of anything. I just couldn’t focus on the task in hand. All I could think of was my pursuers and I felt sure that the guards were looking for me already. They were most likely on their way to the lodgings right then. In fact, they were probably outside the door waiting for me to appear. They’d arrest me and they’d have a great story to tell, and they’d have a long life and success and I’d have the exact opposite. Every now and then I glanced over at the door to see if there was any commotion out on the landing and then back again at the young people sitting over at the table. Eventually, they went out of the room and left me by myself. I didn’t stay long sitting in that shadow-filled room however. Everything in it was battered and broken and the place had a mournful look about it. The chairs were bent and twisted, there was no fire, and there was a clock above the hearth that had said three o’clock for the guts of twenty years. A small statue of a Greek god stood next to the clock and one of its legs was broken and all you could say about it was: ‘How the mighty have fallen!’