18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

My name is Tommy Turnbull. I've been a coalminer all my life. My father was a miner, so was my grandfather, my uncles, my cousins and my brother. Wherever there's a pit, you can bet there'll be a Turnbull somewhere down there.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

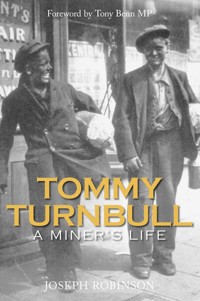

Tommy Turnbull:A Miner’s Life

This is a most enjoyable book ... it would be difficult to find another that expresses so well the texture and feel of a miner’s life and this particular north-eastern community. The people, the incidents, the experience of all Tommy’s family, his acquaintances, including pit ponies and bosses, the entire fabric of the pit and the community, contain all of coal’s sparkle, grit, warmth and corrosive quality; and much, including the language of telling, that is Durham, rather than any other coalfield region. The book is real and raw, not to be read as mere text; yet the expression of the experience is, while remarkable and in many ways as deserving of classic status as Roberts’ Classic Slum or Hoggart’s Uses of Literacy, a text.

John L. Halstead, Labour History Review

I must have read dozens of books about miners’ lives but this one is the best. It’s the best not just because it is a tale well told, though it is, and not because it is superbly informative, though it is that as well. It’s the best because it is about an ordinary bloke and sticks to that. Moreover, it has the clear ring of truth without which biographies signify nothing. Joe Robinson is an accomplished author ... the book offers a wonderfully wide-eyed view of Shields from 1911 ... the sketching is quick, the touch sure. All urban historians ... ought to read these finely shaded passages.

Robert Colls, Northern Review

Joe Robinson has done a magnificent job in giving us a full picture of what life was like at home and in the pit. His account is unsurpassed in recalling the perils the miner found underground. This is a vivid, well written and convincing book.

Philip Bagwell, Tribune

Joe Robinson’s book is in a class by itself. Tommy Turnbull is written in first person, so by the time the story is finished, this shy, obstinate old miner whom everyone liked has become your friend. Here is a book for all young people now coming into struggle, who need to know what life was like for those who went before them in the same struggle half a century ago. It will be read and treasured for decades to come.

Peter Fryer, Workers Press

This story, seen through the eyes of one miner and his family, gives a far more vivid account of what this meant than the dry statistics and cold factual accounts that may be found in some of the official histories of the industry, and I greatly hope that it will be widely read for every sort of reason.

Tony Benn MP

For all miners

First published in 1996 by Tempus publishing

This edition first published in 2007

Reprinted in 2012 by

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port,

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Joseph Robinson, 2007

The right of Joseph Robinson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9971 7

Typesetting and origination by

Tempus Publishing Limited

Printed in Great Britain

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Prologue

The Miner’s Advice to his Son

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Epilogue

Glossary

Acknowledgements

My grateful thanks are due principally to my uncle Tommy Turnbull who told me his life story with such patience and humour even though he was very ill at the time (I didn’t know it but he did), to my aunt, his wife Allie, and his two daughters Anne and Christine.

I am very grateful to my mother Evelyn Robinson for supplying so much family background.

For help with the life of a coalminer at Harton Colliery my thanks are due to the late Paddy Cain of Jarrow and to Freddy Moralees and Les Telford of South Shields. For help with understanding coalmining methodology I am grateful to Dave Temple of TUPS.

I am also indebted to the many miners and their families who have written to me with poems and information over a twenty-year period.

For help with photographs and information I wish to thank Jennifer Gill, County Archivist, Durham County Record Office; Elizabeth Rees, Chief Archivist, Tyne & Wear Archives Service; Barbara Heathcote, Local Studies Librarian, Newcastle Central Library; Miss D. Johnson of Central Library South Shields; Catherine O’Rourke, Celestine Rafferty and Jarlath Glynn of County Library, Wexford, and Trade Union Printing Services, Newcastle upon Tyne.

Thanks to Mark Seddon and Roger Smith for their interest and help.

Thanks to Hannah for help with proof-reading.

Finally, thanks to my wife Judy for her considerable help, skill and encouragement with every stage of the book.

About the Author

Joe Robinson was born in Whitehall Street, South Shields in the house Tommy Turnbull’s wife came from, within sound of the Harton buzzer. Although he has always had a close affinity with pitfolk he became a scientist in the field of medical and veterinary microbiology and worked abroad in hospitals, universities and industry.

Also by Joe Robinson:

The life and Times of Francie Nichol of South Shields

Claret & Cross-buttock

Francie

Pineapple Grill-time (a play)

Chips on My Shoulders

Foreword

By Tony Benn MP

The story of the Durham Miners and their families and of the coalfield where they worked is central to the history of the British working class and the Industrial Revolution they made possible.

Coal was discovered there 400 years ago and it was that coal which fuelled Britain’s economic development in the nineteenth century, not only in terms of its manufacturing industry but also in supplying power to the coal-fired ships which carried our products around the world.

In 1913, there were 166,000 Durham miners at work in 150 pits and it was their labour which gave Britain its pre-eminence in industry.

But, of course, coal mining in private hands led to mass exploitation and it was through trade union organisation that the campaign for the protection of workers’ rights was begun.

The Durham Miners Association was formed in 1869, and in 1908 the Association joined the Miners Federation of Great Britain demanding the Nationalisation of the pits in 1919 which led to public ownership less than thirty years later when the NUM was formed.

For those who worked in the pits it was a story of unending struggle for decent wages, shorter hours, job security, decent conditions and safety underground. Throughout this period there were lock-outs, strikes, police harassment, arrests and imprisonment.

The General Strike in 1926 was the most bitter that there had been and the Durham miners were the ones who stayed out the longest only to find when they returned that there was victimisation, cuts in wages, a lengthening of hours and anti-union legislation.

Now the pits have been privatised again, we should remember the costs of private ownership in lives and injuries in the inter-war years. Between 1927 and 1934 – the years immediately following the General Strike – no fewer than 7,839 miners were killed and over 1,200,000 were injured at work.

This book is about the enormous courage and determination of the Durham colliers who retained a degree of solidarity and optimism and reflected it in the Annual Gala, or ‘big meeting’, which is still held after 100 years even though there has not been a pit in the North East since 1993.

At the Gala a succession of trade union and labour leaders – and a few socialists amongst them – have been inspired by the procession of bands and banners and the huge gathering on the racecourse where the lessons of all this struggle were learned again and passed on to new generations of men and women.

This story, seen through the eyes of one miner and his family, gives a far more vivid account of what this meant than the dry statistics and cold factual accounts that may be found in some of the official histories of the industry, and I greatly hope that it will be widely read for every sort of reason.

Britain has 1,000 years of coal reserves under its territory still, and our recovery will require us to re-open pits and sink new shafts to tap the black gold that lies deep beneath the surface of our country.

But more than that, because the political changes we have to bring about as we approach the millennium can only be achieved if the spirit of the miners and their families can inspire us to fight even more vigorously for the rights we need to live in a decent society free from the new and oppressive exploitation that goes under the name of Globalised Capital.

Tony Benn, MP, 1996

Prologue

When my uncle Tommy Turnbull, the subject of this book, was born, a coalminer’s wage in Britain had hardly altered in a hundred years and, little though it was, it was never long before the money found its way back to where it came from. The house the miner and his family lived in, the shop they bought their groceries in and the pub he had his gill in, were often owned by his employer, the Coalowner. But really it wasn’t a wage at all. It was merely the juggling of payments and fines by the Coal Company. The weighman, who assessed the tubs of coal sent out of the pit by the miner, had the authority to downgrade or reject this ‘produce’ and the duty to penalise its ‘producer’ whenever he could.

In Tommy’s father’s time, a coalminer – a ‘pitman’ he usually called himself – could be thrown in Durham Jail for refusing to work. Bad or dangerous conditions weren’t sufficient excuse for refusing to work. Neither was having to come home with less than he started with because of the weighman’s fines. The Master & Servant Act entitled only the employer to give evidence in a court of law, not the employee. Magistrates, being landowners, were invariably employers, and in coal-producing areas many of them were Coalowners. So any upstart pitman could expect pretty short shrift when his summons arrived.

There was no feeling of loyalty between coalminer and Coalowner, never any of the sentimentality that often existed between farm-worker and farmer – however forelock-touching its nature. Nor was there any of the Yorkshire industrialist’s occasional bequests of homes, hospital wards or parks for their employees. That wasn’t the Coalowner’s style. As far as he was concerned, the only language pitmen understood, was the language of the harsh.

Thousands of men, boys, women and girls had been crushed or suffocated down coal mines over the centuries before HM Government felt obliged to insist that all mine owners sink two shafts instead of just one. But after this costly concession, Coalowners resisted any further expenditure on safety. To them, their employee, the miner, was just an underground peasant, a dirty, ignorant labourer with none of the sensibilities that differentiated noble man from lowly beast.

The Miner’s Advice to His Son

Divvent gan doon the pit, lad

I’ the long run it’s just a mug’s game

Remember, doon the pit, son,

Ye nivver win wealth or fame.

Yor workin’ hard from start till lowse,

At the end, ye see ne gains.

Ye’re rivin’ an’ heavin’ an fleein’ aboot,

An’ it’s sair backs an’ heids for yor pains.

Aa divven’t knaa w’at aa started for,

A must ha’ been wrang in’ the heid,

‘Cos’ many a time when aa’ve had a rough shift,

Aa’ve wished that aa wis deid.

Ye git up at two in the mornin’

Ye haven’t had time for a sleep

The sleep’s still fast in’t corner yor eyes

Ye can hardly see, ye just peep

A bite te eat, an on wi’ yor claes,

An’ off ye gan doon the street

Ye waken the neighbours round aboot,

Wi’ the clatter o’ yor noisy feet.

Ye git te the pit an wait te gan doon

Ready te myek a few bob,

An’ reddy for when its time to gan hyem

Where the pots boiling on the hob.

Ye come back hyem, yor hands on yor belt

Ye feel like faalin’ to bits

It’s only yor belt that haads ye tegether,

Yor sick o’ the sight o’ the pits.

Well, aa’ve dunn me best te warn ye

But A’a divven’t suppose it’ll dee any gud,

Ye’ll not be content till ye git doon the pit

There’s ower much coal-dust in yor blud.

John Thomas Rickaby

1

My name is Tommy Turnbull. I’ve been a coalminer all of my life. And I’ve only God and the Union to thank for not still being one. Over half a century down a big black hole not only miles away under the ground but sometimes under the sea as well. My father was a miner, so was my grandfather, my uncles, my cousins and my brother. Wherever there’s a pit, you can bet there’ll be a Turnbull somewhere down there.

I was born in a two-room cottage in Clink Row, in a pit village by the name of Witton Gilbert on the 7th of June, 1905. My father’s name was Jack and my mother’s name was Annie. My father’s people, the Turnbulls, had always lived there. But the Kellys, my mother’s family, had come over from Ireland when she was just a girl. My father was a hewer and he worked at nearby Bearpark Colliery.

The village of ‘Jilbert’, as we called it, was situated in the North Durham Coalfield, two miles from Durham City. It had one pub, one Walter Wilson’s and one church, and that was a Protestant one. They used to say it was like the catacombs underneath, and that if a couple more shovelfuls had been taken away, the whole place would have vanished. That’s why everything was on a slant.

The cottage we lived in wasn’t the kind of thatched cottage affair you might see on a picture postcard. Any house with no upstairs was called a cottage, no matter what it looked like. It was built of bricks up to about knee height, the rest with wood laths. The wooden part of the walls was creosoted on the outside. The roof, which was also made of wood, was tarred. There was no garden, no gate, railings, path, yard, washhouse, coalhouse or drains. The only outside thing we had was a midden, and we shared that with six other families, along with the tap that was right next to it. If you’d wanted to sound clever, you could have called that side the back. Gas and electric were things you only heard tell of. Folks would say, ‘Oh aye, gas does this and electric does t’other’. To hear them you’d think that when electrification came nobody was ever going to have to lift a finger again. And that all you’d have to do was switch on and lie back.

As you came into the house, the scullery part was first. This was where Mam did all her washing and cooking. And when you crossed over the clippy mat you were in the part we called the living room. In here my father had his rocky chair nearly planted in the fire. And this was where our John and me played when we couldn’t play outside. There was a big fireplace leading up the chimney with an iron heating range at the side. The only light was from an oil lamp that hung down on a chain from the ceiling. You pulled it down to get it going and then shoved it back up out of the way so you wouldn’t bash your head on it. There was one heavy wooden table with two long crackets, and a chair with a spokey back that my mother sat on when she was knitting or darning or if she needed to stop and catch her breath for a minute.

The other room was the bedroom, and everybody slept in there unless any of us was poorly, in which case Mam would bring us into the living room. Night and day the living room was always warm. Although the coal we got from the Colliery was rubbish coal, my mother was able to make do, and the only time the fire was out was when the chimney was being cleaned. She would sort the cinders, take out the ash and blacken the grate, all while the fire was still on, and I never knew her to burn a finger. She could do anything with that fire bar making it talk. The fire, and the huge iron oven it heated, cooked the meals, heated the water we got bathed in and boiled the water the clothes were washed in. And when it was freezing wet outside and you came in needing something extra inside you and there wasn’t so much as a crust to spare, it would help to keep body and soul together. Mam kept the iron shining like silver and the brass polished like gold, and when you heard the sound of the little door opening your heart would give a little jump. To us that fireplace was as close to God as an altar in a church.

In the way of decoration we had wallpaper with a pattern of brown flowery things that had been up so long you could only see the flowers in the top corners where it wasn’t worn or blackened. You wouldn’t see anything like them in a gardening book but they passed for flowers in our house. If ever John and me were carrying on and my father shouted ‘Watch the flowers!’ everybody looked up at the wall, not out the window. Apart from the wallpaper there were a couple of old photos that were so faded you’d have had an easier job identifying the flowers, and a picture of the Sacred Heart in the bedroom. The iron mantelpiece always had vests, underpants and socks hanging from it all the way round, so there wasn’t really room for any other kind of ornament other than the clock, a little candlestick holder and a chipped china dog somebody had won at a fair.

The wooden floor, table and crackets, had been scrubbed so hard over so many years, that if you didn’t keep still you’d get a spelk in your bum as long as your little finger. In our house unless you were sitting on my father’s rocky chair, and you wouldn’t be, it paid you to get straight up and sit straight down.

The whole place was really tiny but being pitfolk we were used to small places. It was comfy, and nobody else’s was any better.

There weren’t many kids of my age in Jilbert, and our John was too small to play with. In any case there was nearly always something the matter with him. So I used to go to my two Grandmas’. There were plenty of uncles at both houses and they were always more than ready to have a bit of carry-on. If they couldn’t find something to make a game out of, they’d chase you around the table. Or if the weather was fine they’d give you a game of footer outside. Not like my father. He was no sooner home, than he was off out again. So when I wasn’t at school I was more at the Grandmas’ than at home. Both Grandmas were very kind to me, and although Grandma Turnbull was very poor compared with us, she’d always find half a slice of bread with a bit of jam or something so you never went away empty-handed.

Granda Turnbull had died a long time ago and all I knew about him was that he’d been a coalminer. Grandma had found it so hard with four children to bring up, that she’d married another miner called Jack Russell who’d lost his wife. Shortly after, Russell had a bad accident down the pit, and though Grandma did everything she could to keep him going, he died and left her with his two to bring up as well as her own. But she was a tough little woman. Her proper name was Isabella but everybody just called her ‘Bella’. Every other woman you knew was called Bella in those days. ‘John’ was the first choice for the lads. Protestant fellers were often called ‘Albert’ or ‘George’, after the King. Protestant lasses were called names like ‘Doris’ and ‘Ivy’. Queens didn’t seem to matter so much.

Except for her shawl, which was as white as her hair, you’d never see Grandma Turnbull in anything but black from head to foot. She was short and stout and had these eyes that looked right into you. She was kind-hearted but she was no mug and she was very firm with her own family. She had to be, with five out of the six, lads. Every one of them was a miner so there was always somebody going out and somebody coming in, and she was up at half past four every day to see to them. You could never see the fire for all the boiling pots on it and the clotheshorses all around and the whole place was as steamy as a laundry. When one of the lads came back for his dinner, off would come the pot with the washing in and on would go the one with the broth. On and off they went all day long, and the only time she went to her bed was on a Saturday night. The rest of the week she just slept in her chair in the kitchen until the latch on the door went.

She wouldn’t use tap water for washing because she reckoned it wasn’t good enough. It was fine for making a pot of tea but not for washing the lads’ shirts. So she collected the rainwater that ran off the roof into a barrel underneath and used that instead. Everything got washed at least twice. Boil and scrub once, boil and scrub twice, rinse once, rinse twice, and then out on the line. The front street of Jilbert looked like Amsterdam, with all the washing flapping like the clappers. Many’s the time somebody’s come racing along on his bike and practically hung himself on a clothes line because a sheet had flapped in his face, especially if he’d one too many gills in him.

When Grandma had finished the washing, ironing and darning which she had to do every day because of all the lads, and was sitting in her chair waiting for one or other of them, she’d have her box of bits of old rags out and would be working away on her clippy mats. They’d have lovely coloured patterns and were so well made that she never had any trouble selling them, when she managed to get them finished that is. Sometimes at night you could hardly see across the room it was so dark yet she’d still be at it. All her life she was plagued with a double hernia but she never stopped working. She was even registrar of births, marriages and deaths for the district. That of course brought in a few extra coppers as well. Every Tuesday there’d be a little queue outside her door and you’d be able to tell by their faces what kind of news each one had come to register.

Making quilts with a Prince of Wales Feathers design was my Grandma Turnbull’s one and only hobby, if you can call it that, because she gave them all away. You could always tell if you were in a Turnbull house by popping your head around the door and looking on the bed, because they all got one. Good they were too, warm as well as fancy.

Although she was poor and did everything herself, neither that nor her trouble ever stopped her from being full of cheer. For some reason she always seemed to be a really happy little roly-poly.

Grandma Kelly wasn’t as tough and hardy a woman as Grandma Turnbull, I never thought, although she was a good bit bigger, but because of her lovely manner and the gentle way she had with her, she was every bit as well liked and every time she put her shawl on and went out for a walk, which she loved to do, people would see her going by and come out of their houses just for the pleasure of having a little chat with her. She wasn’t so full of busy as Grandma Turnbull always was and she’d put things down and make time for you.

Coming from Ireland, and with Granda working on a farm in Esh Winning, which was only a few miles from Bearpark where they lived, both Granda and Grandma Kelly loved animals and the place was always full of them. How they managed it in the little back garden they had was a wonder. Grandma kept hens and ducks and Granda kept pigs, and all of them were great things to play with. If you chased them they’d go fleeing about and make such a din. Other times you just needed to put one foot in the garden and they’d come running after you as though they were going to take a chunk out of you. It depended on the mood they were in.

Grandma used to do the poultry in herself, and the poor things always knew when she was coming even though she always hid the knife behind her back. So did everybody else. You couldn’t blink an eye in Bearpark or in Jilbert without somebody seeing you and telling everybody else. No matter when Grandma came out of the house and no matter how quietly, they’d all know. ‘Oul’ Ma Kelly’s on the hunt,’ they’d say to each other. ‘It won’t be long afore some poor bugger’s head’ll be sayin’ goodbye to its body.’

But Granda could never bring himself to do the necessary with the pigs, and if he hadn’t taken them to market they’d have gone on until they died of old age. If he’d a few ready at the same time, Mr Black, the Co-op butcher from Brancepath, would come. This feller would just walk into the garden and hit them straight over the head where they stood, no messing about. Then he’d cut them up and wrap the pieces in brown paper, load them on to his horse and cart, and away. Mind, quick and handy though he was, they still squealed blue murder and long before he was finished everybody in the street would be patiently standing by with buckets cleaned out and ready in their hands, all hoping for something to make a few sausages or a mince pie with, and maybe something for the cat.

On the occasions when Granda had only one ready and it wouldn’t have been worth Mr Black’s while coming, Granda would get a bit of strong string and wind it round one of its back legs with the intention of taking it to Brancepath himself. In no time the squealing would have all the neighbours out and they’d know exactly what Granda was planning to do. ‘Why divvent ye keep it a bit longer, man? It’s too young for a trip like that. Ye could loss it afore ye get there… Hang on till that one over there’s ready, then Mr Black’ll come and save ye all the bother.’

Just to get this far would have cost Granda a lot of heartache, and no matter how much they pleaded, once he’d made up his mind it was going, it was going.

If I was off school, which I always tried to be, I’d go with them. Brancepath was a real day out. I’d get on the pig’s back and hold on to its big lugs and Granda would be walking behind with the string in one hand, a long stick in the other, and a face as long as a fiddle. Every time it stopped, he would stroke it gently on the behind to remind it of what he had in his hand, and it would take no notice. Then he would tap it, and still it would take no notice. Then he would get mad and give it a really hard whack, and away it would go again, off to meet its maker with me hanging on for all I was worth, and Granda running after it and apologising for hitting it so hard.

There’s a big difference between a horse with a saddle, and a pig’s bare back. A horse’s back has a dip in it put there for sitting on but a pig certainly hasn’t. Its back is as round as a big greasy palony and there’s nothing to hang on to except its lugs which you have to use to try and steer it. When we got to Brancepath and Granda had sold the pig, he’d carry me home on his shoulders. My behind would be sore for days after.

Granda was very soft-spoken and even quieter than Grandma, all the Kellys were the same. They’d come over from Sligo after they were married to make a better life for themselves, and I think they went out of their way to be respectable and well liked. Granda had been a blacksmith before working on the farm, and he was a big, fresh-cheeked, fine figure of a man when he was all dressed up in his swallow-tail coat and his pork-pie hat, his big boots and his walking stick. He was a very strong Catholic and when he went to Mass on a Sunday there was none prouder. He was just a farm labourer but he would never be seen in a muffler and cap with string tied under his knees unless he was at work. ‘Poverty’s bad enough without paradin’ it in front of one and all,’ he’d say.

Even though they were very friendly people, and there were twelve of them altogether, there were never any parties or anything in the Kelly house. I think they were too careful of the law. They hadn’t been over here more than about three years, when they’d got into trouble with the police and the people at the post office, and they never forgot it. Everybody knew about it. Every Christmas Grandma’s sister Anne used to send a turkey and a goose from Ireland and they’d arrive in a brown paper parcel cleaned and drawn and ready for the table. There’d be a lump of butter, a packet of biscuits, and two bottles of poteen. One bottle would be inside the goose, and the other inside the turkey. The reason, it was said, was so that they wouldn’t get broken. Everything had been going hunky-dory for a few years until this one time the paper must have got damp and the turkey came out of its parcel in the post office with the head of the bottle of poteen sticking out of its behind. The pollis was called in and there was quite a to-do. They still got their turkey and their goose every Christmas after that, but never with anything more dicey than a bit of bacon and a few sweets inside.

Grandma Kelly was a handywoman and she was the nearest thing most of the poor people in the district ever got to a doctor. She could give first aid, act as midwife or lay you out if necessary. She had old wife’s remedies for everything and people would come with all sorts of complaints, often as not just for a bit of comfort.

Yet for all she was so level-headed and well used to death and bad accidents, what with the collieries nearby, every now and then she’d go queer and wander off and leave everything. The first Easter Sunday morning after she and Granda had come over to England, their littlest son John had been playing in the burn with two other lads and fallen into a deep pool. He was only eight years old and they never found his body. They always said Grandma would have accepted it if they’d been able to give him a proper burial and Fr Fortin said he would give him one if they could find even a small part of his body. But they never did, not a trace, not even of the clothes he was wearing. Every now and then all through her life Grandma would get it into her head and disappear and they’d always find her in the same place by the burn, bending down with the water up to her shoulders, feeling around for his body and calling out to him as though she was expecting him to come up after all this time. Whenever she was under one of these spells they just let her alone. Sooner or later she’d always come out of it, and then she’d go back home and get on with things as if she’d never been away.

Although their mother and father came from Ireland and they had a background of working in the open air, every one of the Kelly lads went down the pit as soon as they were old enough. Esh Winning, Bearpark, Ushaw and Sleetside, all had Kellys in them. There was nothing else for them to do.

The school I went to was called St Bede’s. It was three miles away in Sacriston and five of us had to walk there and back every day. A pony and trap would have cost threepence a week so we walked even if cats and dogs were coming down. If the nearest Catholic school had been a hundred miles away, we’d still have had to do it. To have gone to a Protestant school and set one foot inside a Protestant church, which you’d have had to do sooner or later, would have meant spending the rest of eternity in Hell with the devils poking you further and further into the flames. At least that’s what Fr Beech said. If my father hadn’t married a Catholic, which he did when he married a Kelly, things would have been different. Protestant hells were nothing like as bad as Catholic hells, which was just as well, because if you weren’t a Catholic that’s where you went.

Catholic schools only had lady teachers, so the parish priest would act as headmaster and his main job was to thrash you. Fr Beech was ours. If you did something wrong outside school, a grown-up would usually say something like, ‘Get out of it, ye little beggar!’ and take a swipe at you which might only get you on the back or miss altogether if you were quick. Not at school though, not with Fr Beech. First you’d be brought out in front of all the lads and little lassies. Then you’d have to stand there while he made a speech that made you feel like the greatest sinner that ever lived. He’d speak slowly with a little smile on his face while pacing from one side of the room to the other, up the aisles and around the back. You’d be standing there on your own during all this and he’d know you were doing your level best not to cry and you knew that when your time came he’d do his damnedest to make you.

Every day without fail he would come galloping up on horseback, the way you see cowboys do on the pictures, fling open the door and stand there looking as though he’d just ridden in from Hell. Then he’d stamp into the classroom in his long coat and long brown leather boots, cracking his whip in the air and whacking it against his leg. You’d sometimes hear kids arguing about whether it’s worse to be hit with a leather belt or a stick but I’ve never heard anybody say there’s anything worse than a whip. And he used that whip far more on us than he ever did on his horse. He wouldn’t have got away with it if he had.

The schoolmaster and Father in the parish before him – Fr Fortin – had been tough enough, my father said, but he had been a great friend of the pitmen and was known throughout Durham as the ‘Pitman’s Priest’. Whenever there was any trouble at the Colliery he would always be one of the first to help. Not only when there was a disaster or an accident, but during a strike or a lay-off when you might have expected a churchman to have no sympathy at all – that was certainly the case with the Anglican Bishop of Durham. During the long strike at Ushaw Moor when many had been turned out of their homes, Fr Fortin brought them into the school – no matter what their religion –and gave them a roof over their heads until they could get sorted out. The same man many a time stood up to the Board of Guardians at the local Workhouse on behalf of the inmates and got the regulations changed so they were allowed a smoke and any other little comforts he could get for them. Fr Fortin never handed money out, his way was to give the wives vouchers to buy food and then square up with the shopkeepers himself afterwards.

Although he was a Catholic priest, his generosity never stopped at Catholics, and everybody raised their caps when he trotted by on his horse. The time he came back from the Boer War, Catholic and Protestant had carried him shoulder-high from the railway station, and when he died they put his coffin in the middle of the playground at St Bede’s School so all the kids could march around and pay their last respects. He had all his vestments on as though he had just lain down for a sleep after saying Mass. He had been born in the West Indies, come all the way to Ushaw College to be trained as a priest, and then just stayed. So they weren’t all the same – not by any means.

2

My father would always be moving from pit to pit to get the best rate he could, and in 1911 when I was six years old we came to live in South Shields. Pits with more water, gas or weak roofs, paid more, and because Harton Colliery was a particularly wet pit the wages were higher than they’d been at Bearpark. My father was a good hewer and knew he could make twelve shillings a week at Harton. He also did part-time insurance work, so he could get more from that as well in a town like Shields with its four big pits. He brought the furniture over on a horse and cart himself, and me and our John came over on the train with Mam because she was expecting our Monica and wasn’t able for the cart.

Coming to South Shields, which was nearly twenty miles away, was like emigrating to Australia. The cost of going back and forth to Jilbert and the time it would take meant we’d hardly ever see our relations. Because of that and other things our lives would now be very different. Shields was divided into villages, and where you lived depended on what you did for a living. The likes of doctors, lawyers and businessmen lived in Westoe. Shipping people lived on the Lawe Top, seamen near the market, and dockers and railwaymen near Tyne Dock. Pitmen lived in Boldon Lane and Whiteleas. My father had found us a terrace house next to a few pit families in Lemon Street, just off Stanhope Road, through somebody he knew. This house and the area we’d come to live in was a very big step-up from what we’d been used to.

The house had an upstairs and a downstairs, and we lived in the downstairs part. In the yard was a small washhouse and coalhouse in one, and a toilet. And all of it we only shared with the people upstairs. In Jilbert they used to come round with a horse and cart once a week to take the stuff from the midden and dump it on farmers’ fields along with the ashes and whatever other rubbish was in with it. The midden cart, the milk cart and the coal cart used to stand side by side in the street.

Here in Shields the Corporation came and emptied the toilets at night and took it away and dumped it off a barge in the sea. You had to put pink disinfectant down the toilet, and keep the rest of your rubbish separate in a bin which the Corporation took away another time. The toilet, which we called ‘the netty’, was big enough to play in, and when it rained we’d play in there for hours.

South Shields was a fantastic place after little Jilbert, and much bigger than Brancepath. There was so much to see and do, and places to go, things I’d never dreamed of. There was the River Tyne which was the lifeblood of North and South Shields, Gateshead, and the great city of Newcastle-on-Tyne which was far bigger even than Durham. Every day of the week huge steam ships would come up the river, many of them with foreign names, blowing their horns and whistles and huge bales, crates and barrels would be loaded off and on to the docks in big rope nets. Hundreds of men would be shouting to the fellers operating the slings, telling them where to set them down, and grabbing them with hooks as they came down.

And then there were the shipyards with their great cranes that went right up into the sky with their massive hooks swinging from side to side. Underneath, huge skeletons of ships half-built stretched out, and rang with the clanging of hammers and sparkled with the welding torches of hundreds of tiny men working inside them.

All kinds of bridges crossed the river. One carried the London to Edinburgh express and all the freight trains, another carried local trains from Sunderland and South Shields through Gateshead and across the river to Newcastle. There was a swing bridge that swung away from both banks to let the big ships get up the river. You could sit on one of the great coils of rope on the quayside and wonder how they ever got the different parts of the bridges to stay up while they were building them and about the brave men that must have worked on the very top with huge spanners, sometimes in bitterly cold weather. Every time I was on the Tyne Bridge it was always windy and yet every single part had been properly painted inside and out, on the top and underneath. Nowhere had been skimped, not even the parts that seemed impossible to get at.

On Sunday mornings the quayside was a different place altogether. It was a market for all sorts of things and nothing cost more than a few pence. Quacks and tricksters would be gathered there selling their wares, doing their acts, and up to every kind of trick. You could see and hear it all and it didn’t cost you a farthing.

You could never go down to the River Tyne without there was something going on. Sometimes they had rowing races with world champion scullers, and everybody would be shouting and cheering as though they were at a horse race. One boat might go flying ahead at the start, and you’d think the other ones had had it. Then one of them would move up and the other might drop back, just the tiniest bit, and this would give the others the encouragement they needed. Everybody would be yelling like mad as they went neck and neck and you could see the long muscles in their arms and legs, and their faces screwed up as though they were in agony. Then as soon as the winner passed the finishing line, all the foghorns would blast and the ships’ whistles would blow, and everybody would be jumping up and down.

Shields even had its own railway stations and trams, so if you had the money you could go anywhere. It had parks with shuggy boats and swings, lawns to play on, trees to climb, and lakes chock full of tadpoles and tiddlers. There were tennis courts where you could watch them batting the ball back and forward, and when you got fed up with that you could chuck gravel at them. They could never catch you because they were trapped inside the wire. On Sundays there were bandstands with iron seats where you could sit and listen to the music and have a bit of a laugh at some of the players.

Down town there was a proper market that was always packed with people and stalls with rough men and women shouting and yelling one on top of the other. There were streets like Fowler Street and Ocean Road with big stores you could go in for a poke around, and variety halls with pictures of famous singers and dancers and magicians and comedians that were coming soon, maybe that very night.

Best of all were the beaches. Sand was great stuff to play on, and the sea was fantastic. There were pools with crabs and queer fish in them, and winkles under rocks. There were cliffs and caves and lovers to spy on in the dunes. There was even an all-year-round fair with swings and stalls where you could win things if you were lucky. And if you looked hard enough you could always find a few coppers or a silver threepenny bit in the grey grass, usually in front of stalls like the coconut shies where people got excited and got their money out in a hurry. As soon as anybody won on a particular machine or stall or anything, everybody would run over thinking they could do the same. They were far more careless there than in the amusement arcades. In the arcades even though farthings and halfpennies were going in non-stop, most of the ones having a go were kids and if they dropped anything they’d practically tear the ground up to get it back.

I never thought there were that many kids in the whole world as there was in Shields. Anywhere you went there was somebody to play with or at least who wanted a fight. There were a lot more pollises as well. I’d only seen two in the whole of my life before I came to Shields and that includes Brancepath. Here they had more to do than come up and start bossing you about for nothing at all. My mother was once taken to court when we lived in Jilbert just because I’d kicked a tin can in the street on a Sunday. Here it didn’t seem to matter, there was so much else going on. Even if you broke a window or snapped a branch off a tree, they’d never know who to blame unless you just stood there with a silly look on your face. In Jilbert if a window got bust or some apples got pinched, they always came knocking on our door because I was the only kid of an age that would do that sort of thing, or so they reckoned. If they knocked on the door of every house in Shields with kids in it every time an apple went missing off a tree, they’d never have had time for anything else.

The people themselves weren’t much different though and we were still living among our own kind. Many of them had come in from the country for the better wages, and my father would have known a canny few of them already. His own brother Jim was one. Not that it would have mattered if he’d known them or not because pitmen and pitfolk are always the same wherever you go. You could walk into any pit house at ten o’clock at night and you’d find the same thing. A red hot fire, a tired-looking woman, and heavy damp clothes hanging up all over the place.

At Harton they called my father a ‘hillbilly’ because he came from Jilbert, and he called them ‘sand-dancers’ because Shields was on the coast. Pitmen had all sorts of daft names for things and for each other, and it would only take them a couple of days to give somebody a nickname that would stick with them for the rest of their life.

In parts of Durham and down into Yorkshire they used ‘thee’ and ‘thou’ a lot, but not because they were particularly religious or anything. Ones that would be cursing and swearing all day long would be ‘thee’ing’ and ‘thou’ing’ along with everybody else. That was the way they spoke in different districts and not just the pitfolk. But the difference between the speech of ordinary people living on the north side of the Tyne wouldn’t be as different from those living on the south side, as it might be between two pits that were only down the road from each other. And any Shields miner could tell which of the four Shields pits, Harton, St Hilda, Boldon or Whitburn, a man came from, as soon as he opened his mouth. My father tried to drop the thee’ing and thou’ing when he came to Shields because the fellers used to take the mickey out of him, but he could never get rid of it entirely. It came out whenever he lost his temper and always with his own people. Sometimes you could hardly understand a word when he and Uncle Jim were going on at each other. He used to say to my mother, ‘Ye might put on airs and graces with the rest of the world but ye can never get away with it with your own brother. My God, he’d give ye credit for nowt.’

If my father was coming off shift during the daytime, I’d go to meet him whenever I wasn’t at school. I loved to watch him coming across the colliery yard with all the men with their black faces and white eyes and mouths, and hear the clatter of their boots. I’d be waving and shouting ‘Dad! Dad!’ But he wouldn’t pay any attention. If he saw me he might nod if he was in a good mood, but he’d just carry on. I’d follow behind till all the others had gone their own way, and then I’d run up. ‘How, Dad!’

He’d never stop or slacken his pace. ‘Well, what’ve you been up to, ye little bugger? The schoolboard man’ll be round lookin’ for ye, if ye divvent watch theesel’.’

When we got home and went in the door, Mam would always leave what she was doing and go half over to him, which was as close as she’d get, and say the same thing, ‘Have a good shift, Jack?’ She’d stand there wiping her hands on her apron and looking at him but he wouldn’t give her a look. ‘It’s over now, and that’s all that matters,’ he would say as he hung up his jacket and cap and went to get washed.

Even if my father wasn’t coming off shift, I’d still go up to the Colliery with the other kids if ever I was playing anywhere near and heard the buzzer. It was the greatest sight in the world to see men coming out of a pit. There were no pit ‘lads’ as far as we were concerned. Anybody who dressed like a man, worked at the pit and got filthy black, was a man. Sometimes one of your pals’ big brothers would leave school and get started at the pit. Straightaway he was different and would never be the same again. Sometimes the big lads would play centre-forward or goalie with us kids if there wasn’t enough of them to get up a game of their own. But not after they started at the pit. From then on they were men and would never be seen dead playing with ‘daft bloody kids’.

As soon as the buzzer went we would climb the railings and sit on top of the wall. The men would teem out of the pit in all shapes and sizes. Some would have their caps set at a jaunty angle to show they were right ones with the lasses, others would have theirs pulled straight down like fighting men, while others would have theirs at the backs of their heads as if they couldn’t care less about anything. The young ’uns would be wearing jackets that were too big for them or too small for the buttons to be fastened. Others had pants that were way above their ankles or turn-ups halfway up to their knees.

When they first came into the yard they’d all be mixed up together, but by the time they got to the gates they’d have sorted themselves out according to their own drift. Like a rabble army they’d come marching by, every one as black as the Ace of Spades. The younger ones would always be at the front, shouting and laughing, pushing and shoving, and chasing each other. They thought they were men, but inside they were as daft as we were, and still as full of energy, even after eight hours down the pit. Next would come the middle-aged ones arguing the toss. Then the old fellers, quiet and grim and very tired. Last of all would come the stragglers with bad backs and gammy legs and those who couldn’t walk far without stopping to catch their breath.

By the time the first lot had reached the gates, a stream of bicycles would have caught up with them and the young’uns among them would be racing each other out. You could see them trying to knock each other off. Some of the ones without bikes would pitch in and try to drag somebody off. Others would be jeering. Then one would topple over and crash into the middle of the older men coming up behind. ‘Get out of it, ye stupid buggers!’ a shout would go up. After a few catcalls back and forth and a few threats, and maybe a few chases with somebody running cursing after them for a bit, everything would quieten down and everybody would go their own way.

Everybody told the time by the colliery buzzer. ‘Eeeh, it must be half an hour since the buzzer went. If I divvent get me skates on, the cobbler’s’ll be shut. Wor Bob’ll gan mad if I divvent get his boots for him.’

Most of the time it was a very homely and comforting sound. It was the pit calling out to the women at home to tell them their men were coming home, and that they could start setting the table. It meant the pit was in business and the men were in work.

Everybody listened for the buzzer; they planned their lives around it.

3

Every night I’d lie in bed and hear the same pantomime outside the window. First the sound of heavy boots would come clomping up the lane together with raised voices and then they would stop. There’d be a couple of long louping steps, followed by a couple of short quick ones for balance.

‘Whoops!’

‘Watch theesel’, thou stupid bugger!’

Then a double lot of clomping, grinding, sliding and cursing, as if people were pushing each other about.

Two miners full of stout, even little ones like these were, can make a hell of a noise, especially in a cobbled back lane in the middle of the night. I’ve heard many a horse pulling a wagon, sometimes big ones like Clydesdales with feet like capstans and a driver bawling out to the women in their houses but none that made more noise than my father and my Uncle Jim coming back from the Stanhope Hotel.

‘Thou thinks like an imbecile... Thou talks like an imbecile... And thou looks like an imbecile. And nebody… nebody in their right mind, that is... could have a reasonable discussion with anybody… like that.’

‘There’s an ould sayin’... and I’m ganna give it thou for nowt... “It taks an idiot... to know one”. And if we’re seriously talkin’ about looks... If I looked like thou… thou knows what I’d do? I’d break every bloody mirror in the house... That’s the first thing I’d do. The next thing I’d do is drown meself.’

‘Listen who’s talkin’! Thou’s ne oil paintin’. And thou wouldn’t need ne expert to tell ye that.’

‘Ahht, shut thee gob!’

There’d be a laugh like a foghorn followed by a few more shouts and curses. Then a noise like a donkey braying. Those laughs were like nothing else on earth. The foghorn would be my father, and the donkey would be Uncle Jim. They were always laughing at one another in between arguing, because each of them thought the other was an idiot for not seeing things the way they did. They argued about the Colliery, the Government, the Labour Party, Newcastle United, Sunderland, what it would be like in Heaven and what it would be like in Hell. There was nothing on the earth, above the earth or below the earth that the two of them didn’t argue about. My father wasn’t so bad with anybody else, drunk or sober. Though that’s not to say he was the easiest man in the world to get along with, because he wasn’t. But when he was with Uncle Jim, drunk or sober, they were like flint and steel.

After they’d been at it more than long enough my mother would get up and go out.

‘Hush, Jack. Ye’ll waken folks up.’

‘Aye, all right, pet... I’ve just been tellin’ him the same thing.’

‘It’s not me, thou bloody liar! It’s thou!’

‘She knows who’s makin’ all the noise…don’t ye, pet?’

‘Is that you, Jim?’ my mother would say, knowing it couldn’t be anybody else. ‘Like a cuppa tea before ye go home?’ She knew he wouldn’t say yes at this time of night, there’d be ructions enough as it was when he got home. Not all pit wives were as soft as my mother, not by a long chalk and certainly not Aunty Ethel.

‘No, thanks, lass. I’d best be on me way. Talkin’ to this husband of yours is like talkin’ to a bloody brick wall. I never realised until tonight just how thick he really was. As a babby we always thought there was somethin’ wrong wi –’

‘Shut thee gob, will thou! If thou art gannin’... gan… afore they come an’ lock thou up.’