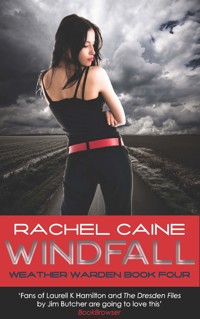

8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: Weather Warden

- Sprache: Englisch

UNNATURAL DISASTER Weather Warden Joanne Baldwin has defeated her longtime enemy and saved the world - again. But at what cost? Standing at ground zero for the last attack, Joanne, the Djinn David, and the Earth herself have been poisoned by a substance that is destroying the magic that keeps the world alive. Joanne and David have already lost their powers, but that's just the beginning. The poison that has seeped into the planet is destabilising the entire balance of power, bestowing magic on those who have never had it and taking it at critical moments from those who need it. It's just a matter of time before the delicate balance of nature explodes into chaos, destroying mankind - and every living thing on earth - with it.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 474

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Total Eclipse

WEATHER WARDEN BOOK NINE

RACHEL CAINE

To all the wonderful people who’ve supported Joanne’s adventures through this series – THANK YOU. You all rock.

But I’ll single out one, because she was the first totell me that the idea for Ill Wind was a good one.

Thank you, Sharon.

OK, I lied; I will single out two, because about the time I was going to give up on this whole writing gig, I talked with fantastic writer Joe R. Lansdale, and he gave me the encouragement I needed to keep on defying gravity. Thank you, Joe. And hey, thanks for Bubba Ho-tep, too, while I’m at it.

Contents

Title PageDedicationWhat Has Come BeforeChapter OneChapter TwoChapter ThreeChapter FourChapter FiveChapter SixChapter SevenChapter EightChapter NineChapter TenChapter ElevenChapter TwelveEpilogueSound TrackAcknowledgementsAbout the AuthorBY RACHEL CAINECopyrightAdvertisement

What Has Come Before

My name is Joanne Baldwin, and I used to control the weather as a Weather Warden. These days, I can also control the forces of the earth, such as volcanoes and earthquakes, and the forces of fire. Don’t ask – it’s a long story. Just go with it, OK?

Controlling all those awesome forces sounds like fun, eh? No. Not when it makes you a target for every psycho world-killing danger that comes along.

Good thing I’ve got my friends at my back – Lewis Orwell, the most powerful Warden on the planet; Cherise, my best (and not supernatural) friend; a wide cast of sometimes dangerous allies who’ve got their own missions and agendas that don’t always match up with mine.

And I’ve got David, my true love. He’s also a supernatural Djinn, the fairy-tale-three-wishes kind, and he’s now coruler of the Djinn on Earth.

But not even the most powerful friends in the world can help when real devastation hits. And it hit me and David, dead center, in our final battle with my old mentor and enemy … and it took our power away.

For me, that’s an inconvenience.

For David, it’s fatal.

I have to find a way to fix this before it’s too late to save my beloved – and maybe even humanity, because Mother Nature is waking up … and she’s pissed.

Chapter One

Black corner.

It was the name Wardens – and Djinn – gave to a section of the world that had been scorched by something unnatural; a place where the basic energy that coursed through the world, the pulsebeat of the Earth, no longer existed.

A black corner looked fine, but to anyone with sensitivity to power, it was desolate and sterile. Wardens – those who controlled the basic powers of nature – suffered when they were trapped inside one of these dead zones. Still, we got off better than the Djinn.

Djinn died.

We’d been trapped in the massive black corner, sailing hard for the horizon, for days, and it was taking its toll at an increasingly horrible rate.

It was so hard, watching them suffer. It was slow, and painful, and terrifying to watch, and as our cruise ship sailed ever so slowly through the dark, empty seas, trying to get outside the supernatural blast radius, I began to wonder whether we would make it at all. The New Djinn – the Djinn who’d been born human and had become Djinn during some large-scale disasters – were in a lot of pain, and slipping away.

Still, they fared better than the Old Djinn. Original, eternal, with no real ties to humanity at all – they declined far faster. In a very real sense, they couldn’t exist on their own, without a direct connection to power – a connection that was nowhere to be found now, even though we were many miles out from the site of the disastrous ending to our fight with my old enemy. He’d opened a gateway to another dimension, and what had come through had almost destroyed me and David; it had definitely blasted the entire area for hundreds of miles in all directions.

I couldn’t imagine what the consequences of that were going to be. It was a terrible disaster, and I felt responsible. Hell, who was I kidding? I was responsible, beyond any shadow of a doubt. I was recovering from the after effects of the long battle and the injuries I’d gathered along the way, but that was secondary to the guilt I felt about how I’d handled things.

I should have been better. If I’d been better, none of this would have happened. I wouldn’t be watching my friends and allies suffer. I wouldn’t be watching helplessly as the best of them, the ones who’d given the most, lost pieces of themselves.

Dying in slow motion.

Lewis Orwell, the head of the Wardens, my old friend, the strongest human being I’d ever met … Lewis had developed a perpetual, deep-chested cough that sounded wet and thick. Pneumonia, maybe. He looked as if he hadn’t rested in weeks, and he probably hadn’t. His reserves were used up, his body beginning to shut down in protest.

And still he was up in the middle of the night, sitting with the Djinn. Offering them what little comfort he could. There weren’t so many of them … not now. We’d seen three of them die in the past twenty-four hours. The ones who were left were sinking fast.

Djinn were exotic and beautiful and unbelievably powerful. Seeing them laid so low was heart-wrenching. I didn’t know how Lewis could stand it, really. The misery hit me in a thick, sticky wave as I limped into the small infirmary, and I had to stop in the doorway and breathe in and out slowly to calm myself. No sense in going overwrought into this mess. It wouldn’t help anyone.

Lewis was sitting in a chair next to a bed that held a small, still human form the size of a child. Venna – who’d always borne an uncanny resemblance to the famous Alice, of Lewis Carroll renown – was still a pretty thing, with fine blond hair and big blue eyes. The supernatural shine that usually seemed a few shades too vivid for human eyes was missing now. She looked sick and afraid, and it hurt me deeply.

I sank down on the other side of her bed and took her hand. Her gaze, which had been fixed on the ceiling, slowly moved to rest on me. She felt cold. Her fingers flexed just a little on mine, and I felt rather than saw the faintest ghost of a smile.

‘Hey, kid,’ I said, and smoothed her hair back from her face. ‘How are you?’

It was self-evident how she was doing, but I didn’t know what else to say. Nothing I could do was going to help. Like Lewis, I was utterly helpless. Useless.

‘OK,’ she whispered. It seemed to be a great effort for her to form the word, and I saw a shudder go through her small body. I tucked the blanket closer around her, although I knew it wasn’t going to help. The chill that had sunk into her couldn’t be banished by warm covers and hugs and hot toddies.

We’d tried putting the Djinn on the deck of the ship, hoping the sunlight would help revive them, but it had seemed to make things worse. Venna – who had been alive as long as the Earth, as far as I could tell – had cried from the sheer, desperate agony of being in the sun and not being able to absorb its energy.

It had been awful, and here, inside, she didn’t seem as distressed. That was something, at least.

We were no longer trying to save them. We were just managing their decline.

Venna’s china blue eyes drifted shut, though it wasn’t exactly a natural sleep; she was conserving what energy remained to her. The Old Djinn burnt it faster than the New Djinn, it seemed. We’d already lost the only other Old Djinn on board – a close-mouthed sort I’d never gotten to know by name.

And, in truth, I loved Venna. I cared about her deeply – in the way you’d care for a beautiful, exotic, very dangerous animal who’d allowed you to become its friend. I’d never thought of her as fragile; I’d seen her slam tanker trucks aside with a wave, and fight monsters without getting so much as a hangnail.

It was hard to see her look so helpless.

Lewis looked almost as bad – worn down and fighting to keep himself together. I met his eyes, which were bloodshot and fever bright. ‘Go to bed,’ I told him. ‘I’ll stay with them for a while.’

‘And do what?’ he snapped, which hurt; I saw the flare of panic in his face, quickly tamped down. He hadn’t meant to say it, though of course he’d been thinking it. They were all thinking it. ‘Sorry, Jo. I mean—’

‘I know what you mean,’ I said softly. ‘But the fact is that you’re just as handicapped as I am right now, and you’re punishing yourself by wearing yourself down to nothing. Lewis, you can’t. You can’t. When we get out of this, the Wardens will need you more than ever. You can’t be running on fumes when the rest of them need you. This is going to get a lot worse. We both know it.’

I could see that he wanted to tell me not to preach to him, but he bit his tongue this time. He knew I was right (not that it would stop him from arguing), and on some level, he was aware that he was hurting himself as punishment. Like me, he felt that he deserved it.

He looked down at Venna. I saw it in his face, all that weariness, that guilt, and a fair amount of bitter self-loathing.

‘Lewis.’ I drew his gaze and held it again. ‘Go to bed. Go.’

He finally nodded, rose – had to steady himself against the wall – and left. I looked around the room, with its sterile high-tech beds and medical facilities that could do nothing about the problem we were facing. Every bed was filled by a Djinn.

And every Djinn was, to a greater or lesser extent, dying.

The Djinn Rahel – a New Djinn, and one of the oldest friends I had among their kind – turned her head slightly to look toward me. Rahel had always seemed invincible, like Venna – polished, wildly beautiful, with her elaborately cornrowed ebony hair and lustrous dark skin, and eyes that glowed as if backlit by amber.

Now she seemed so diminished. So fragile. Her eyes were still amber, but pale, faded, and … frightened. She didn’t speak. She didn’t have to. I patted Venna’s hand, then got up and went to Rahel’s side. I put the back of my hand against her forehead. She felt hot and dry, consumed by some bonfire inside.

‘Well,’ she whispered with a shadow of her old, cocky charm, ‘isn’t this peculiar? The lamb caring for the wolf.’

‘You’ve never been the wolf, Rahel.’

‘Ah, sistah, you don’t know me at all.’ She heaved a slow, whispering sigh. ‘I have played at being a friend to you, but I’m nothing but a wolf. We all are, even your sweet David. Djinn are born because we are too ruthless to accept our own deaths as humans do. It suits us ill to face such an end as this.’

‘It’s not the end.’

‘I think it could be,’ she said, and closed her eyes. ‘I think it will be. And so I will tell you something I’ve never told you, Joanne Baldwin.’

I swallowed hard. ‘What?’

Her lips took on the ghost of a smile. ‘I am glad that we have been friends. You remind me of someone I knew long ago. My cousin, in breathing days. You have her soul. And I am glad to have looked on that brightness again.’

‘Stop it,’ I said, my voice unsteady. ‘Just stop it. You’re not going to die, Rahel. You can’t.’

‘All things can. All things should, in the end.’ She didn’t sound angry about it, or sad, or afraid. She just sounded resigned. ‘The world is changing. That is not a bad thing, you know. Just different.’

Maybe she had the perspective of millennia, but I didn’t, and I was sick and tired of things being changed. I wanted it all to go back to the way it was.

I wanted peace.

But I didn’t say anything else to her, and she lapsed into a quiet, waiting stillness, conserving her energy. The room was eerily silent, all those immortal creatures counting the minutes until they ceased.

And it was my fault.

I put my head down on the crisp, clean sheets next to Rahel’s hand, and silently wept.

I felt a hand touch my hair, and thought at first that it was Rahel. But no; her hand was still exactly where it had been, limp and unmoving on the covers. I took in a deep breath and sat up, swiping at my eyes and sniffling.

David looked down at me, and for a moment we didn’t say anything at all. He looked almost as bad as the Djinn lying in the beds, although he’d been spared that particular fate; his decline was slower, more insidious.

There was still a connection between us despite the hit we’d taken when Bad Bob had done his worst at the end. Our powers were gone, and David was trapped in mortal flesh, but on some level he was able to bleed off just a little power from me. Enough to survive, at least temporarily.

The difference was that when we sailed out of the black corner, the Djinn would get better. David wouldn’t get his powers back that way. Neither of us would. And if he couldn’t reconnect to the aetheric, he would get weaker.

I read the misery and concern in his eyes, and took his hand in mine. Touching flesh would have to do; we couldn’t touch in all those familiar supernatural ways. It felt oddly remote and clumsy.

‘You OK?’ he asked me.

I nodded. ‘As long as you’re here. You?’

That won me a faint smile from him, and a widening of those honey brown eyes. He was still beautiful, even contained in human form. He’d lost that glowing, powerful edge, but what was left was pure David. As time went on, I had the sense that I was seeing the David he’d once been – a friend, a lover, a warrior in days that had come and gone well before any history we knew.

Not a good Djinn, but a good man.

Still, he hadn’t been just a man in so, so long. And I wondered whether he could go back to being just that, just human, without dying inside of regrets.

David’s smile faded as he looked at Rahel, replaced by that intense focus I knew so well. He didn’t speak, but I knew how deeply he was feeling his own helplessness. I was feeling exactly the same thing. I leant my cheek against his warm, strong hand, and his thumb gently stroked my cheekbone.

Small comforts.

‘Lewis left you alone here?’

Yeah, there was no part of that that didn’t sound accusatory toward Lewis. ‘I made him leave. He was exhausted,’ I said. ‘And there’s nothing he can do except what I’m doing. What you’re doing.’

‘Stand here and watch my brothers and sisters die?’ He paused, shut his eyes for a second, and then said, ‘That sounded bitter, didn’t it?’ I measured off an inch of air between my thumb and forefinger. He sighed. ‘I feel that there ought to be something. Something we can think of, do, try.’

‘We have, we did, and we will. But we’re not exactly at the top of our game, honey.’

‘I don’t know what this game is,’ David said softly. ‘I don’t like the rules. And I don’t like the stakes.’

‘Well, at least you have a good partner,’ I said. ‘Later, we can kick ass at table tennis, too.’

He bent and kissed me – not a long kiss, not a passionate one, but one of those sweet and lingering sorts of promises that comes from deep, deep down. Passion we had, but we also had something else. Something more.

Something that mattered to me more than my own life. I’m not going to lose him, too, I told myself. I wondered whether that panic and determination showed in my face. I hoped not.

Just as David was pulling up a chair next to me at Rahel’s bedside, the door to the ship’s hospital opened, and Cherise staggered in, burdened by a tray so huge that it should have come with wheels and its own parade clowns. She was a tiny little thing, drop-dead gorgeous even under the ridiculously stressful conditions. Somehow she’d found the time to shower, make her hair shampoo-commercial shiny and full of body, and scrounge up clean, attractive sexy-girl clothes, which today included shorts and a striped shirt – a look I was sure I couldn’t have pulled off without looking like a very sad Old Navy reject. She had no makeup on, but then again, Cherise didn’t really need any. She had that kind of skin.

I got to my feet to help, but David was already there, taking the tray and setting it on a side table. Cherise let out a long sigh and shook her hands and arms to release the stress. ‘Man,’ she said. ‘I forgot how hard it is to be a waitress. Remind me not to work for tips again, unless it involves a pole.’ She looked up at David and flashed him an infectious smile. ‘You get what that means, right?’

‘Do pole vaulters get tips?’ he asked innocently, and lifted the silver cover on one of the large platters on the tray. He reached in and snagged a piece of bacon, which made my mouth water suddenly; I couldn’t remember the last time I’d eaten. Ever.

Cherise stared at him with a wounded expression. ‘That’s a joke, right? Please tell me you are joking, because if you’re not joking, that is just tragic, and I’m going to have to stage an intervention.’

David munched bacon and explored the rest of the buffet she’d delivered as I got up from my chair. ‘Strippers. Poles. I understand.’

‘Thank God. Because if a hottie like you had never seen a stripper, my faith in God was going to …’ Cherise suddenly clammed up, which wasn’t like her at all. She looked down, then around at the silent, still Djinn. ‘Yeah,’ she finished very quietly. ‘Guess that ship has sailed. And, oh look, we’re on it.’

It wasn’t like Cherise to fail to find the sunny side of the cloud, but then again, we’d been under clouds for what seemed like years at this point. I guessed that even the eternal optimist had to reevaluate, given the circumstances.

‘How is everyone else?’ David asked. I reached over him to take a slice of bacon as he poured coffee from the small thermal pot.

‘The Wardens are all freaking out because they’re Joe Normals,’ Cherise said. ‘For me, it’s just another sunny day in paradise, really. Not that I’m in the mood to tan or anything.’

She really was depressed. Well, I could see why … She was probably the only person on the entire ship, other than the hired crew, who couldn’t feel anything odd about the area through which we sailed. The Wardens were reduced to shakes and panic, feeling suffocated by their isolation, and they probably resented her for her lack of suffering.

I was starting to actually get used to it. A little.

The food helped steady me, and I could see David’s body language easing a little as well. He hadn’t needed to pay careful attention to his metabolism in, oh, about five thousand years or so, and since he’d originally been killed and reborn as a Djinn at the tender age of what was probably his early twenties, if that, it wasn’t too likely he’d ever experienced the kind of human trials I was already starting to put up with.

My mother used to say that getting old isn’t for sissies. Neither is being human, for that matter. And the fact that David had managed to pull himself together so fast, and so gracefully, was humbling. I hadn’t functioned nearly so well when I’d, in turn, been pulled over to the Djinn side. That should have been a lot more fun than it turned out to be.

The ship’s motion had increased a little – difficult to tell, in a ship this big, but I could feel the pitch and yaw deep in my guts. If I’d still been a Weather Warden, I’d have been able to tell a whole lot more – how the air was moving, the tides, the deep and complex breathing between the water and the air above. Two kinds of fluids, moving as one. Symbiotic.

Now all I could tell was that my stomach was rolling with the motion. Great.

‘The captain says we should be able to dock in a couple of days,’ Cherise said. ‘I don’t know about you guys, but I could dig my toes in some sand. I’m starting to feel like I’m lost on Gilligan’s Island. And I can’t even be Ginger, because I don’t have any evening gowns.’

David stopped in the act of lifting a grape to his mouth. Just … froze. And I thought maybe he was confused about the pop culture reference, but that wasn’t like him, and anyway, he didn’t usually just …

Every Djinn lying in the beds suddenly sat straight up and screamed.

It was an eerie, tormented, unearthly wailing sound, and shockingly loud. I staggered, dropping my glass, pressing both hands to my ears, and setting my back against the wall for primal protection. There was something wrong with that sound, deeply and horribly wrong. Cherise crouched, covering her head; if she was screaming I couldn’t hear her over the incredible, deafening sound of raw pain coming from every one of the Djinn.

Every one of them but David, who was pale, standing frozen in place, and unable to make a sound or movement. His eyes, though – his eyes were screaming.

It seemed to go on forever, the needle-sharp sound piercing the fragile barrier of skin and bone I’d put over my ears. It shattered into my brain, filling it with a horror I’d never experienced and wasn’t sure I could survive. I felt my heart racing, thudding in panic against my ribs, and my knees failed me. I slid down the bulkhead wall.

I was weeping hysterically, struggling to catch any hint of a breath. It felt as if the sound itself were a weight on me, driving the air from my body …

And then, as suddenly as it had started, it cut off. Not because the Djinn stopped screaming.

Because the Djinn, every single one of them except David, had vanished in a nicker of cold blue light.

Gone.

David fell hard, eyes still wide and locked in a terrible, panicked stare. I peeled my hands away from my ears, gathered strength, and managed to crawl on shaking hands to where he lay. I sat and pulled his head and shoulders into my lap as I stroked his hair and face. His skin felt ice-cold and clammy. His color was awful.

I couldn’t hear anything, just the ringing echo of that awful, eternal scream. I wondered whether I’d gone deaf. I thought I’d hear that sound for the rest of my life, or until I went mad, but I realised it was slowly fading. I could hear Cherise gasping and crying a few feet away. She’d collapsed on her side, curled into a ball. Her hands were still pressed to her ears.

‘Baby,’ I whispered to David. ‘Baby, talk to me. Talk to me.’

He tried. His lips parted. Nothing came out, or if it did my damaged ears couldn’t separate it from the still-ringing echoes of the screams.

He was shuddering. As I watched, he curled himself on his side, like Cherise, and pulled his knees up.

What just happened?

In seconds the sick bay door slammed open, and at least a dozen Wardens pelted into the room, with Lewis in the lead. He looked as shell-shocked as I felt, but at least he was on his feet and moving. He took it in at a single glance – Cherise, me, David, the empty beds where the Djinn had been.

The breath went out of him, and he went pale. Lewis took a slow, deliberate second, then turned to face the other Wardens. ‘Kevin, see to Cherise,’ he said. ‘Bree, Xavier – get David into a bed. Warm blankets.’ He crouched down to put our eyes level, and whatever he was seeing in my face, it obviously didn’t comfort him. ‘Jo?’

I tried to speak, then wetted my lips and tried again. The two Wardens he’d delegated were taking hold of David’s arms and helping him rise. He wasn’t able to offer much in the way of assistance. ‘I don’t know,’ I finally managed to say. ‘Something – happened.’

‘Where did the Djinn go?’

I just shook my head. My eyes blurred with tears. I felt lost, alone, cut off, horribly frightened. Lewis reached out and gripped my hands in his.

‘Jo,’ he said. ‘Jo, listen to me. I need you to focus. You need to tell me what you saw. Tell me what you heard.’

I tried to remember, but the instant I did, that sound filled my head again, as fresh and hot and painful as before. Shatteringly loud. I clapped my hands over my ears again, and dimly heard myself screaming, begging him to make it stop.

The next thing I knew, I felt a small, hot pain in my arm, and then the sound was fading, drifting away along with the light and the pain and everything in the world.

Darkness.

Silence.

Chapter Two

The first thing I heard when I woke up was a distant, soft echo of screaming. With it came a jolt of adrenaline, a feeling of drowning, of being consumed by something … massive.

Then it receded, like a tide, and I was left shaking and cold despite the piles of warm blankets on top of me. Lewis was asleep in a chair next to my bed, leaning forward with his head resting on the covers next to me. One long-fingered hand was touching mine, very lightly.

He was snoring.

I smiled wearily and ruffled his hair. ‘Hey,’ I said. ‘How can anybody sleep with that noise?’

Lewis sat up, blinking, wiping his mouth, and looking so cutely rumpled and abashed that I felt something in me wobble off its axis. Don’t look like that. Oh, and please don’t look at me like that while you’re doing it. He was tough enough to resist when he wasn’t being adorable.

‘Sorry,’ he mumbled, and scrubbed his stubbly face with both hands. ‘Bad night.’ Some focus came back into his eyes, and I was able to get that wobbling part of me back in balance. ‘How are your ears?’

‘I could hear you snoring like a chain saw. I must be healed.’

That got a grin from him, brief as it was. ‘Then I guess they’re intact.’

I looked around. David was lying in the next bed over, still asleep. He looked pale and tired and anxious, even resting.

Cherise was curled in on herself in the next bed after David.

‘How are they?’ I asked. I was afraid of the answer, but he just nodded briskly, and relief flooded in on me in a warm wave. ‘No lasting damage?’

‘Worn-out,’ he said. ‘David was able to talk a little before he drifted off. Cherise just needs sleep.’

‘He told you—’ My brain flashed back to the screaming Djinn, that sound, and I felt the panic race back, slamming into my body and jolting me into a sudden sitting position. It wasn’t as loud this time. Or I was getting used to hearing that awful, awful noise. I swallowed several times and concentrated hard, and the screaming died away.

I was holding Lewis’s hand in a death grip. I eased off, remembering to breathe, and saw the worry and fear in his face. ‘I’m OK,’ I said. If I said it enough, maybe it would even be true. ‘David told you—’

‘About the Djinn disappearing,’ Lewis said. ‘We heard the – the sound out there, everywhere in the ship. According to radio communications, we weren’t the only ship that heard it. It blew out speakers on a tanker ten miles out. It came from the Djinn? You’re sure?’

I nodded, not sure I could trust my voice just then. I was controlling the effects of the experience, but my body was still reacting in flight-or-fight mode. Finally, I said, ‘They just screamed and vanished. I don’t know what happened.’

‘I do,’ Lewis said. ‘We reached the edge of the black corner.’

I stared at him. I hadn’t felt … anything. No change in my perception of the world. No connections snapping back in place.

I was still cut off.

That shouldn’t have surprised me, but it did. It felt as if all the props had just been knocked out from under me, as if some joker had pulled the handle on a trapdoor and I was going to fall forever. I’d said I understood what had happened to me, but deep down inside, I’d believed – I’d believed that I was better than that. That my power would come snapping back, and once we were beyond the borders of the black corner, I’d be … myself.

Lewis could tell. I hated to see the pity in his face, so I looked away, fighting back the tears. I couldn’t do much about the trembling, though. ‘So,’ I said, and forced my voice to be something like normal. ‘The Wardens are back in business?’

‘More or less,’ he said, and broke up into a fit of wet coughing. Once he’d gotten that out of the way, he smiled ruefully. ‘Some are feeling better than others. Jo—’

‘We knew this was going to happen,’ I interrupted him. ‘David and I. We knew our powers were … gone. We just have to figure out how to get them back.’

‘It’s possible that they’ll come back on their own, over time. That your body will be able to repair the damage.’

‘Don’t bullshit me, Lewis. I’m not a child, and I don’t want false hope.’

‘I’m not offering any,’ he said. ‘Look, we just don’t know. Things are – nothing makes sense right now. The Djinn … the way things feel—’

‘What about the way things feel?’ I thought he was talking about the two of us, and that was dangerous, uncertain territory. But he wasn’t, as it turned out.

‘The world isn’t right,’ Lewis said. ‘Things are wrong out there. Badly wrong. Bad enough that it blew the Djinn out like candles once they came out into the storm.’

My breath caught in my throat, and I grabbed his hand again. ‘They’re not—’

‘I don’t think they’re dead,’ he said. ‘But they’re not visible to us, not anymore. I can’t reach any of them, even on the aetheric. It’s like they’ve been – taken.’

‘But what if they’re more than gone? What if they’re—’

‘They’re not dead,’ he repeated. ‘I’d know if they were. Hell, the whole world would know, I think.’

I shuddered, trying hard not to think about that. If the Djinn were gone, one of the key support structures in the delicate architecture of the planet had disappeared, sending us screaming off balance into the dark. We wouldn’t survive that. Any of us, including Mother Earth herself. The Djinn were like antibodies in her bloodstream, designed to attack and defend her against dangerous infections. She needed them.

‘So what now?’ I asked. Lewis yawned, tried to cover it up, and failed miserably. ‘Besides about a month of bed rest for you, and inhalation therapy, and a boatload of antibiotics?’

‘Yeah, like that’s going to happen. We both know the reward for a good job is more work, only done faster and more difficult.’

He wasn’t wrong about that, but I didn’t know how much more Lewis could take. He’d been through as much as I had – more, maybe, depending on how you count such things. And he didn’t have a loved one’s strength to rely on. Lewis only had himself.

And whose fault is that? a little voice whispered nastily in my head. Who shoved him away? Who ran off and fell in love with somebody else?

It didn’t matter, I told that little voice as firmly as possible. Things were what they were. Lewis knew I cared for him, but David was my love, my lover, my husband. We all had come to accept that.

I thought.

Lewis was watching me, and I couldn’t fathom what was going on in his head. I hoped he couldn’t guess the argument going on inside mine, either.

‘We’re two days from port,’ he said. ‘Once we get there, we need to hit the ground running. There are reports of all kinds of problems breaking out.’

I shook my head. ‘Not exactly new.’

‘Not exactly,’ he agreed. ‘But we’re the mechanics of the world, Jo. And things need to be fixed. So most of the Wardens will get back to doing what they do best.’

‘Most,’ I repeated. ‘Meaning?’

‘Meaning that I’m going to pull the top three Earth Wardens, and we’re going to do our best to analyze what happened to you and David, and make it right if we can. I’ve been on the phone to Marion Bearheart. She thinks that, in theory, it should be possible to open up the energy conduits within you again, if that’s what’s gone wrong.’

That sounded hopeful. It also, at second breath, sounded painful. I winced a little, and saw sympathy flash across Lewis’s face. ‘Yeah,’ he said. ‘It’s going to hurt.’

‘Used to that.’

‘And David?’

Signing myself up for painful psychic surgery was one thing, but David …

‘David can speak for himself,’ said a voice from the next bed, and Lewis turned in that direction. Behind him, I saw that David had pulled himself up to a sitting position, chest bare, sheets wrapped tight around his waist. He looked tired and vulnerable, but the sight of him up and alert made my heart take a mad leap of joy. ‘What do humans take for headaches these days?’

‘Depends on how bad it is,’ Lewis said, already moving in the direction of the locked medicine cabinets. ‘On a scale of one to ten?’

David thought about it, then sighed and rubbed a distracted hand over his short brown hair. ‘Twenty-five.’

Lewis didn’t seem surprised. He retrieved a preloaded syringe, came back, and unceremoniously delivered a jab to David’s biceps. David flinched, lips parting in shock, and said, incredulously, ‘Ow!’ He sounded horribly betrayed by the pain. I wondered how long it had been since he’d really been subject to a human nervous system – one he couldn’t control, anyway. ‘What was that?’

‘Wait for it,’ Lewis said, as he disposed of the hypo in a medical waste container. ‘Should be about – now.’

David suddenly relaxed – not quite enough to collapse, but I saw the tension just bleed out of him. His eyes widened and went a little unfocused. ‘Oh,’ he said. ‘Well, that’s better.’

‘Welcome to modern medicine.’

‘It’s nice,’ David said, and raised his eyebrows. ‘It’s really nice.’ He slid off the bed, landed on his bare feet, and padded over to claim the chair Lewis had been using. Before he sat, he bent over and kissed me, long and sweet and slow, and I savored every bit of it.

Lewis cleared his throat.

‘Oh, bite me, big man,’ I said, too full of relief to care. ‘You’re OK, honey?’ David’s skin felt warm against my hand – human warm, not the banked fire of a Djinn. He gave me a small, reassuring smile. ‘Really?’

‘I’ll be fine,’ he said, and sat down. ‘As long as you are.’ He turned his head toward Lewis, and his body language altered itself, just a little. Although I couldn’t get the subtleties, it seemed to me that he was making an effort to be friendly, but he wanted Lewis to be anywhere but here. ‘Lewis. What do you know?’

‘About what happened to the Djinn? Nothing. We came out of the black corner, they screamed, they disappeared.’

David’s eyes went briefly blank, and I knew that, like me, he was struggling not to relive that awful sound. There was something about it that just wouldn’t die; it was like an endless recorded loop, playing in the back of my mind. The best you could do was keep the sound turned low. ‘No,’ he said. ‘That’s not what happened. Jo understands.’

I did? I didn’t. I shook my head.

‘You saw it before,’ he said. ‘At the coast. You saw it take me.’

I had no idea what he meant, and I was about to say so. And then it came to me, like a physical slap. I sat up, staring at him. ‘No.’

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘Exactly that.’

‘But – the Wardens would know.’

‘Not if she didn’t wish them to.’

‘Excuse me,’ Lewis said, a little too loudly. ‘Somebody want to clue me in?’

David was the one to say it, which was good, because I wasn’t sure I had it in me. ‘It’s the Mother,’ he said. ‘It was her scream, echoing through the Djinn. She’s been hurt, and she’s angry. She gathered the Djinn to her. They’re in her power now.’

I watched Lewis’s face go very quickly pale. He put out a hand to steady himself. ‘You’re saying—’

‘I’m saying that the Earth is awake,’ David said. ‘At least, I believe she is coming awake. The Djinn serve her, and when she calls, they must come.’

This was, beyond any doubt, the worst thing that could happen. The Earth slept. We liked it that way. Even in sleep she was difficult, but once that vast, slow consciousness was roused … we had no idea what she would do, except that it almost certainly would end in extinction for a great many species, and the end of human civilisation, at the very least. The Earth could not be reasoned with, or even directly communicated with. Not even the Djinn could do that. The only ones that had a chance, even a whisper of a chance, were the three Djinn Oracles.

Thinking of the Oracles made me think about my daughter, Imara, and I felt a leap of terrible fear. Had she screamed, like the others? Had she lost herself, too?

‘No,’ David said, and his fingers tightened on mine. ‘She’s all right, Imara is all right. We’d know—’ His voice trailed off, and I saw a flash of panic in his eyes. We wouldn’t know. We were only human now, and our daughter, our child who’d been born half Djinn and raised to become an Oracle … she was beyond our grasp now. David normally would have been able to reach out to her, over any distance, but now he was just as trapped in flesh and as clueless as I felt. We both turned immediately to Lewis.

‘I don’t know about the Oracles. I haven’t heard anything,’ he said. He knew immediately what we were thinking about, and the frown on his face said that he was worried about it, too. ‘I’ll get somebody on it. David, do you know why she summoned the Djinn?’

‘Pain,’ David said softly. ‘You heard the scream. That was her pain.’

It rolled over me in a fresh, overwhelming wave of memory, and I had to concentrate hard to keep myself from shaking with the intensity of the experience. ‘The black corner,’ I said. ‘She’s been hurt. That’s why she’s waking up. We did this.’

David visibly swallowed, then nodded. Our hands tightened together, the only real comfort we could offer each other. It had been bad enough when we’d been responsible for the pain and death of Djinn. Now we might be responsible for a whole lot more.

‘We’ll find a way to get back to ourselves,’ he said. ‘We have to find a way.’

I wished I could believe him. Lewis wasn’t looking at me, and I could tell that he was trying not to reveal his own doubts. He pushed away from the bulkhead wall and said, ‘You asked what we were going to do. I don’t see that there’s any reason to change the plan. We hit land, the Wardens scatter to handle crisis events. I’d like you two at Warden HQ for the time being. It’ll be easier to work with you there, and you can help us with coordination.’

Coordination.

If the Earth was really waking up, really angry, really hurt – we’d be coordinating firefighting during a nuclear war. And it was a waste. He was sidelining us, and I didn’t like it.

‘We have something more important to do, Lewis. I know you’re trying to keep us out of the way, but we have to try to find a way to get our powers back,’ I said. ‘David can’t live like this. You know that. We have to see the Oracles. If anybody knows, they do.’

‘I can’t give you help.’

‘We don’t need any,’ David said. ‘This will work, or it won’t. But isn’t it worth a shot?’

Lewis thought about it for a moment, then nodded. ‘Yes,’ he said. ‘It’s worth a shot. But if it doesn’t work, I need you at Warden HQ. Understand?’

‘Understood,’ I said.

No way in hell.

I got used to feeling sealed inside myself over the next two days; if David didn’t, he hid it well. We didn’t need confinement in hospital beds, so we checked ourselves out while Lewis wasn’t looking. It wasn’t really our fault, though. Cherise instigated it.

‘No way am I sleeping in this horrible bed the rest of the trip,’ she declared within a couple of hours of waking up. For Cherise, she looked ragged. For anyone else, she looked magazine-cover ready, but I could spot the subtleties – a smudge under her eyes, a slight pallor under her tan, hair that wasn’t quite as bouncy as usual. ‘And the shower in here sucks. What is this shampoo stuff, anyway? Medical soap? Ugh. No. I am not doing without product. There’s a limit.’

With that, and without anybody giving her permission to vacate the bed, she was up and moving, wrapped in a sheet and searching for her clothes. David helped – more afraid that she’d end up dropping the sheet and he’d see more of Cherise than he intended, I think – and once she’d laid her hands on her shorts, shirt, and shoes, there was no stopping her.

Which was all fine with me, actually. I was heartily sick of this room. I dressed quickly. David was hilariously slow; I wondered how often he’d actually had to pull on his own pants in the last few thousand years. Probably zero times.

‘Sunshine,’ Cherise declared as we followed her out of the medical area and into the more spacious public area of the ship. The utilitarian carpet and walls were replaced by lusher stuff the higher we went, and by the time we could see daylight streaming through windows, we were in posh territory, with fancy sitting rooms and dark wood paneling. And bars. A lot of bars. A few were even serving.

Cherise stopped at one and ordered us all margaritas.

‘I don’t think this is the time—’ I said, but she pressed the glass into my hands firmly.

‘Sweetie, this is exactly the time to drink,’ she said. ‘We survived, right? We’re heading home? Definitely happy hour, from now until, oh, ever after.’ She clinked glasses with me, then David, and led us out a side door onto the deck of the ship. We didn’t much feel like celebrating, but it was tough to resist Cher when she was in a mood like this.

And she was right about taking us outside. It was beautiful.

Hard to believe that we’d spent the last few weeks – no, months? years? – under such strain, facing such dire circumstances. When we’d sailed out of Miami, we’d done it in the teeth of a monstrous storm.

Today the sun was warm and kind, the sky a rich, clean-scrubbed blue. The breeze that blew in off the waves was gentle as it glided over my bare arms. The sea was calm; it glittered in diamond-bright swells, a sparkling fabric unrolled as far as the eye could see.

So beautiful.

David put his arm around me, and we stood there for a moment in silence, staring out at the vista. Cherise leant on her forearms on the rail, smiling, turning her face up to the sun with an expression of pure delight.

‘Cher?’

She turned at the sound of her name, and I glanced back to see Kevin coming at a run from a lower deck, taking the stairs two at a time. My relationship with Kevin – the youngest Warden we had, I believed – was complicated. He was complicated, more than most people I knew: damaged, and dangerous, and unpredictable, but still struggling to find and hold on to that core of goodness that against all odds survived within him. He’d been through a lot, in his – what was it now, nineteen years? He was three years younger than Cherise, which seemed like a lot at their ages. But that didn’t stop him from being head over heels in love with her.

‘Hey, Kev,’ she said, turning from the rail as he jumped to the top of the steps and lunged to grab her in a hug. She was a very small girl, and he was tall and lanky, putting on more muscle all the time. An odd couple, but also oddly appropriate for each other. Cherise’s unending optimism was something Kevin needed in his life, which had seen way too much darkness. She was laughing in bright, silvery peals as he spun her around in his arms. ‘Whoa, whoa, easy, don’t make me yak!’

He stopped and let her go, but she didn’t go far – just far enough to kiss him, with authority. David raised his eyebrows a little but said nothing. I wondered what he thought about it. I suspected he was just as wary as I was of Kevin, generally.

‘You’re OK?’ Kevin asked. ‘Lewis said—’

‘Yeah, look, the Djinn kind of freaked out and there was a thing, but I’m all good now. See?’ Cherise did a runway twirl for him. ‘I’m fine.’

‘Yes, you are.’

She made a purring sound low in her throat and arched against him like a cat. ‘Don’t tease unless you mean it.’

‘Oh, I—’ Kevin suddenly stopped in midflirt, blinked, and looked at her with a baffled expression. David and I both turned to look at him. Cherise was just as baffled as Kevin, it seemed.

‘What?’ I asked, because it didn’t seem like Cherise could even remember the word.

Kevin closed his eyes for a second, rubbed them, and opened them again. Relief spread across his face, and he shook his head. ‘Nothing,’ he said. ‘Jesus, I’m tired. I thought – it’s nothing. I’m OK.’

Cherise stepped forward and put her hand against his cheek, one of those loving gestures that I find myself doing to David so often. Kevin relaxed and bent toward her, covering her hand with his. ‘Well,’ I said to David, ‘they’ve gotten cozy. Not really sure how I feel about that.’

He acknowledged it with a nod, but I could tell his mind was elsewhere. Shadows in his eyes, weariness in his face. For the first time, it struck me that every minute he spent in a human body – a real human body, cut off from the Djinn – he was growing older, just as I was. I tried to imagine how it felt for him to have lost so much, to be so alone. I knew how I felt. Surely for him it was millions times worse.

‘David.’ I put a hand on his arm, and got his full focus. ‘Are you OK? Do you need Lewis to—’

No mistaking the weary twist of his mouth. He hated being dependent on anyone, but he’d have to face facts – he couldn’t draw enough power from me to fuel his life well, and Lewis was the best bet. But David didn’t like being beholden to the first man I’d ever loved. At all. ‘I’m fine,’ he said, voice unnervingly soft and even. ‘If I have to see him for help, I will.’

I didn’t believe him, but he wasn’t asking me to, in so many words. It was the big lie, and he was asking me not to push it. David wasn’t the kind to be reasonable about his limits; after spending millennia without many at all, he was going to crash into human borders pretty hard, and it was going to hurt.

It wasn’t the kind of thing he’d thank me for pointing out, either.

‘Coordinating,’ I said, bringing us back to the dark center of things around which our lives revolved now, ‘He really wanted to stick us with coordinating at headquarters.’

That got a smile from him, if a brief one. ‘It’s not going to suit you if we have to do it.’

‘Speak for yourself, Master of’ – I was about to say Djinn but caught myself in time … ouch – ‘the obvious. I’m not giving up yet. We’ll find a way to get our mojo back. See if we don’t.’

David drained the rest of his glass and dangled it from his fingers, staring down now into the sparkling waves. ‘You sure you want it back?’

‘Are you kidding me?’

‘No,’ he said, and his voice had that odd, flat, soft inflection again, as if he were pressing all the emotion out of it with great care. ‘Jo, think about it. We both want to be together, but we’ve always been of two worlds. I tried to make you part of mine, but that didn’t work. This – this is a chance to make me part of yours.’

I forgot all about the drink in my hand, the beautiful day, the laughter of Cherise and Kevin standing a few feet away, and fixed him with a disbelieving stare. ‘David, you’re dying.’

‘Everyone’s dying,’ he said. ‘Mortal life is short to someone like me even in the best case. If I don’t – resume my life as a Djinn, I can be a true husband to you. Living a human life.’ His eyes finally moved to meet mine. ‘Giving you human children.’

We didn’t talk about Imara very often; our Djinn child was a beautiful, complicated gift, but she had never been a baby, never rested in my arms, never taken her first steps. The mothering instinct in me craved more, and he knew that. I’d never said it, but of course he knew.

‘David—’

‘It’s not a good time,’ he finished for me, and he was right on, even though we no longer shared that deep supernatural bond that had made it so easy for him to read me. ‘I know. But there’s so little good about all this, Jo. We should take what we can, when we can, for as long as we can.’

‘I’m not having children just to watch them die, if this turns bad,’ I said, and somehow managed not to add, again. Imara’s death, before she’d been made an Oracle, was something that would haunt me forever. ‘We’re in trouble. Don’t think I haven’t noticed.’

‘You know what I’ve learnt from thousands of years of watching humanity? It’s always a bad time.’ He put his arms around me and held me, and the simple warmth of it made me want to weep. I didn’t. It wouldn’t do for me to get all girly and soft on him now. ‘But all the bad times end, too.’

‘Thus sayeth the dude with a long view.’

‘Dude?’

‘Sorry, it was my bad eighties teen years coming back to haunt me.’

He kissed me, as if he couldn’t think of any more words. That was OK. It got the point across just fine.

It was very strange to be on the outskirts of the whirlwind of activity inside the Wardens – a bystander, like Cherise. Someone included me in some of the meetings, out of courtesy, but being outside of the direct flow of crisis information made me feel like I was just holding down a chair at the table. It was, in fact, a literal table, the biggest one on the ship, and it seated about twenty; I supposed they used it for swank corporate meetings on the high seas. Or really large families, with equally large checkbooks. Lewis sat at one end, looking down the long expanse of wood; around it, every chair was filled with some powerful Warden or other.

Except mine and David’s, of course. We were just keeping the cushions warm.

We were an hour into the meeting, and what had started out as a grim list of problems had only gotten worse.

‘Reports coming in from South America,’ said Kyril Valotte, an exotic-looking young man who missed being handsome by the narrow set of his eyes. ‘Earthquakes and lava flows in Venezuela. We’ve got teams heading there now, but we’ve also got reports of odd animal attacks in Panama, some kind of disease outbreak in Guatemala … It’s a lot for the Earth team to handle at once.’

‘I can send four Wardens out of Texas,’ said the head of the Southwest US. region, and made some notes on his map. ‘Earth Wardens I got. Weather Wardens I need.’

‘I’ll send as many as I can,’ Kyril said with a nod. ‘We’ll need ground transportation.’

I held up my hand. ‘I’ll take it. I can still make phone calls.’

They looked up, and I saw the frank confusion in their faces for a second before memory caught up. Then they both just looked uncomfortable. Kyril nodded and murmured something meaninglessly kind. The US Warden – Jerry something? – didn’t bother. He just went back to his maps.

There was a lot of that going on. Lower-ranked Wardens came in and out, delivering notes and whispered messages to their bosses, and with each note, the deployments ended up revised. Thankfully, Cherise had come to my rescue with a genuine computer and network uplink, so I was dispatching travel authorisations and setting up rental cars at the speed of – well, not light, but at the speed of whatever satellite I was bouncing my signal from. It was something useful to do, at least.

I was glad, because listening to the trouble was somehow worse than not knowing about it at all.

Lewis looked at his watch and said, ‘Hour update,’ which was the trigger for us to go around the table, one by one, and list off the emerging issues, the ones being handled, and estimated numbers of casualties. I tallied it up in a spreadsheet. Nice and clean and neat.

By the time silence fell again, and my fingers stopped typing, I was shaking. The pause was deep and profound. I stared at the list of things I’d recorded.

‘Jo?’ Lewis’s voice was gentle. He already knew.

I cleared my throat. ‘We’re up to more than a thousand reported anomalies and severe issues,’ I said. ‘Estimated casualties worldwide are climbing steadily. Right now, from what we have reported, the worst case scenario puts human lives lost at about half a million people.’

People who were bad at math took in sharp breaths around the table.

‘It’s going to get worse,’ David said, in the silence. ‘The Djinn aren’t intervening. I believe they could be causing some of these events.’

‘Why? Why would they do that?’ It was an emotional question, not a rational one, and it came from Kelley, down near the end of the table. She was upset, clearly.

‘Because they don’t have a choice,’ David said. ‘The Djinn aren’t operating under their own control anymore. At least, I don’t believe they are. Otherwise, at least one of them would be here now. You can’t count on any assistance from the Djinn, and where you meet them, you have to consider them as hostile.’

We all knew what that meant; hostile Djinn were pretty much worst-case scenario all by themselves, and they were now only a part of our problems. I felt sick and light-headed, and I was pretty sure from the faces around the table that I wasn’t the only one.

‘Focus on what we can control,’ Lewis said. ‘We’re dispatching Wardens to cover the hot spots, but that’s reacting. We need to get ahead of this.’

Someone let out a hollow laugh. ‘How?’

‘We need to get to the source of the problem,’ Lewis said. ‘We need to get to the Mother herself.’

This time, I felt David take a breath. A sharp one, which he let out slowly before saying, ‘I don’t think that’s a good idea.’

‘I realise that we’re just humans,’ Lewis said, ‘but sooner or later, she needs to understand what she’s killing.’