4,49 €

4,49 €

oder

-100%

Sammeln Sie Punkte in unserem Gutscheinprogramm und kaufen Sie E-Books und Hörbücher mit bis zu 100% Rabatt.

Mehr erfahren.

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Jillian Wayne

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

- Illustrated Edition: Beautifully curated with 20 evocative illustrations

- Includes Bonus Material: Concise summary, character list, and author biography

This illustrated edition brings the world of the novel to life with 20 expressive images that highlight pivotal scenes and deepen emotional resonance. Whether you’re discovering the book for the first time or revisiting it with fresh eyes, these visuals enrich your reading experience without overshadowing Stowe’s powerful prose.

What you’ll love inside:

A gripping, accessible narrative that moves swiftly from Kentucky hearths to New Orleans salons and the harsh fields of the Deep South.

Unforgettable characters—the steadfast Uncle Tom, brave Eliza and George Harris, angelic Little Eva, conflicted Augustine St. Clare, and the infamous Simon Legree.

Enduring themes of family, faith, moral responsibility, and resistance that still resonate today.

Clean, reader-friendly formatting for both eBook and print, designed for immersive reading sessions or classroom study.

Bonus features make this edition ideal for students, book clubs, and lifelong learners: a clear, captivating summary to orient new readers, a quick-reference character list to keep everyone straight, and a concise biography of Harriet Beecher Stowe that situates the novel in its historical moment.

Rediscover why this landmark book became a catalyst for conversation and change.

Add this illustrated classic to your library today and experience the story that still speaks to the heart.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

0,0

Bewertungen werden von Nutzern von Legimi sowie anderen Partner-Webseiten vergeben.

Legimi prüft nicht, ob Rezensionen von Nutzern stammen, die den betreffenden Titel tatsächlich gekauft oder gelesen/gehört haben. Wir entfernen aber gefälschte Rezensionen.

Ähnliche

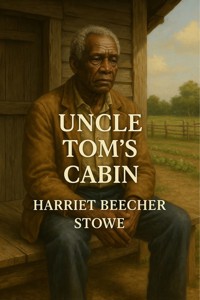

Uncle Tom’s Cabin By Harriet Beecher Stowe

ABOUT STOWE

Harriet Beecher Stowe: The Pen That Stirred a Nation

Early Life and Influences

Harriet Beecher Stowe was born on June 14, 1811, in Litchfield, Connecticut, into one of America’s most intellectually and religiously influential families. Her father, Lyman Beecher, was a fiery Calvinist minister known for his sermons on social reform, and her mother, Roxana Foote Beecher, was a woman of deep moral conviction who inspired Harriet’s compassion and intellect. When her mother died at an early age, Harriet found solace in books and faith—a pattern that would define her life’s purpose.

Educated at the Hartford Female Seminary, founded by her sister Catharine Beecher, Harriet was introduced to the idea that women’s education could be a tool for social change. Her early writings reflected both her literary promise and her growing awareness of the injustices that plagued society.

From Teacher to Writer

In the 1830s, Harriet moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, where her father became president of Lane Theological Seminary. Living on the border between the free North and the slaveholding South exposed her to the brutal realities of slavery. The stories she heard from fugitive slaves and the violence of anti-abolitionist riots awakened a moral fire within her. Writing became her weapon.

She married Calvin Ellis Stowe, a biblical scholar and fellow abolitionist, in 1836. Together, they raised seven children, balancing domestic life with their commitment to faith and reform. Calvin often encouraged Harriet’s literary ambitions, famously declaring, “You must be the one to write that book.”

The Birth of a Cultural Earthquake: Uncle Tom’s Cabin

That book became Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852)—a novel that would shake the foundations of a divided nation. First serialized in the National Era, the story of the saintly slave Uncle Tom and the cruelty of his oppressors galvanized the abolitionist movement. It sold over 300,000 copies in its first year and was translated into dozens of languages, becoming one of the 19th century’s most influential works.

Stowe’s vivid characters and moral clarity humanized the enslaved and exposed the hypocrisy of Christian slaveholders. Her work was not without controversy—southern critics denounced her as a liar and agitator—but her impact was undeniable. When she later met President Abraham Lincoln in 1862, he allegedly greeted her with the words:

“So you are the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war.”

Later Life and Literary Legacy

Stowe continued to write prolifically, publishing novels, essays, and travel memoirs, including Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp (1856), which further explored themes of resistance and moral conscience. After the Civil War, she turned her attention to domestic fiction, exploring the complexities of womanhood, spirituality, and moral growth.

In her later years, Stowe lived in Hartford, Connecticut, where she became a neighbor and friend to Mark Twain. Despite periods of declining health and memory loss, she remained a symbol of the power of conscience in literature.

Harriet Beecher Stowe died on July 1, 1896, leaving behind a literary and moral legacy that transcended her era.

Legacy and Impact

Stowe’s pen became a moral compass for a nation in turmoil. She demonstrated that fiction could do more than entertain—it could transform hearts, challenge systems, and rewrite history. Today, she is remembered not only as the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin but as a pioneer of social justice literature, an early advocate for women’s voices, and a testament to the enduring power of empathy.

As Stowe once wrote:

“The truth is the kindest thing we can give folks in the end.”

SUMMARY

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel follows Uncle Tom, a deeply faithful, dignified enslaved man sold down the river to pay his master’s debts, and Eliza, a young mother who bolts from Kentucky the night she learns her son will be sold. As Eliza and her husband George Harris race north—across the breaking ice of the Ohio River, into Quaker safe houses, and toward freedom—Tom is sent south, first to the gentle household of Augustine St. Clare in New Orleans, where Tom befriends St. Clare’s angelic daughter Eva, and later into the brutal hands of Simon Legree, a plantation owner who tries to crush Tom’s spirit.

Eva’s compassion briefly softens the world around her (even pricking the conscience of the mischievous Topsy and the proper Miss Ophelia), but after Eva and St. Clare die—St. Clare before he can legally free Tom—Tom is sold to Legree. On Legree’s plantation, Tom refuses to betray two enslaved women who are trying to escape. For his steadfastness, he is beaten to death, forgiving his killers and holding to his faith to the end. Meanwhile, Eliza and George finally reach safety and ultimately emigrate to Liberia, determined to build a free life.

Why it endures:

Moral clarity: Stowe turns abstract politics into flesh-and-blood urgency—exposing slavery’s cruelty while insisting on the full humanity of the enslaved.

Iconic scenes: Eliza’s flight across the ice; Eva’s luminous kindness; Tom’s martyrdom—all became cultural touchstones.

Call to conscience: The novel galvanized anti-slavery sentiment in the 1850s and helped ordinary readers see complicity, courage, and redemption in stark relief.

Core themes: Christian love and sacrifice, the corrosive power of a profit-driven system, motherhood and family, racial justice, and the possibility—and cost—of moral resistance.

CHARACTERS LIST

Main Characters

Uncle Tom —A devout, kind, and steadfastly moral enslaved man whose faith anchors the novel.

Eliza Harris —Brave enslaved mother who escapes to save her son from being sold.

George Harris —Eliza’s intelligent husband; a skilled worker who seeks freedom and dignity.

Simon Legree —Cruel plantation owner who tries to break Tom’s spirit.

Augustine St. Clare —Tom’s gentle New Orleans master; sympathetic yet morally indecisive.

Little Eva (Evangeline St. Clare) —St. Clare’s angelic daughter whose compassion changes hearts.

The Shelby Plantation (Kentucky)

Mr. Arthur Shelby —Tom’s original owner; sells Tom to pay debts.

Mrs. Emily Shelby —Moral, kind; opposes slavery.

George Shelby —The Shelbys’ son; admires Tom and later frees the enslaved on his estate.

Aunt Chloe —Tom’s wife; warm, witty, and strong.

Harry —Eliza’s little son, the child at the center of her flight.

Sam & Andy —Enslaved men who use humor and cunning to delay the slave-catcher.

Mr. Haley —Hard-nosed slave trader who purchases Tom and hunts Eliza.

On the Run / Allies & Pursuers

Senator & Mrs. Bird —Ohio couple; she persuades him to help Eliza.

Tom Loker —Rough slave-catcher who is later reformed after being cared for by Quakers.

Marks —Loker’s sly associate.

Phineas Fletcher —Resourceful Quaker who aids Eliza and George’s escape.

The St. Clare Household (New Orleans)

Marie St. Clare —Augustine’s self-absorbed wife; dismissive of the enslaved.

Miss Ophelia —Augustine’s upright cousin from Vermont; learns to confront her own prejudice.

Topsy —Enslaved child given to Ophelia; mischievous but capable of deep love and growth.

Prue —Enslaved woman broken by suffering, showing the system’s cruelty.

Alfred St. Clare —Augustine’s strict brother; argues for harsh control.

Henrique St. Clare —Alfred’s son; fond of his enslaved playmate yet shaped by privilege.

Dodo —Henrique’s enslaved playmate (also called Adolph in some editions).

The Legree Plantation (Louisiana)

Cassy —Enslaved woman of sharp mind and tragic past; plots escape.

Emmeline —Young woman bought by Legree; escapes with Cassy.

Sambo & Quimbo —Legree’s brutal overseers; later shaken by Tom’s forgiveness.

Notes on Themes Through Characters

Faith & martyrdom: Tom, Eva

Moral awakening: Miss Ophelia, Tom Loker, George Shelby

Systemic cruelty: Legree, Haley, Marie St. Clare

Resistance & motherhood: Eliza, Cassy, Aunt Chloe

If you’d like, I can turn this into a printable one-page study sheet or add brief quotes for each character.

Contents

VOLUME I

CHAPTER I—In Which the Reader Is Introduced to a Man of Humanity

CHAPTER II—The Mother

CHAPTER III —The Husband and Father

CHAPTER IV—An Evening in Uncle Tom’s Cabin

CHAPTER V—Showing the Feelings of Living Property on Changing Owners

CHAPTER VI—Discovery

CHAPTER VII—The Mother’s Struggle

CHAPTER VIII—Eliza’s Escape

CHAPTER IX—In Which It Appears That a Senator Is But a Man

CHAPTER X—The Property Is Carried Off

CHAPTER XI—In Which Property Gets into an Improper State of Mind

CHAPTER XII—Select Incident of Lawful Trade

CHAPTER XIII—The Quaker Settlement

CHAPTER XIV—Evangeline

CHAPTER XV—Of Tom’s New Master, and Various Other Matters

CHAPTER XVI—Tom’s Mistress and Her Opinions

CHAPTER XVII—The Freeman’s Defence

CHAPTER XVIII—Miss Ophelia’s Experiences and Opinions

VOLUME II

CHAPTER—Miss Ophelia’s Experiences and Opinions Continued XIX

CHAPTER XX—Topsy

CHAPTER XXI—Kentuck

CHAPTER XXII—“The Grass Withereth—the Flower Fadeth”

CHAPTER XXIII—Henrique

CHAPTER XXIV—Foreshadowings

CHAPTER XXV—The Little Evangelist

CHAPTER XXVI—Death

CHAPTER XXVII—“This Is the Last of Earth”

CHAPTER XXVIII—Reunion

CHAPTER XXIX—The Unprotected

CHAPTER XXX—The Slave Warehouse

CHAPTER XXXI—The Middle Passage

CHAPTER XXXII—Dark Places

CHAPTER XXXIII—Cassy

CHAPTER XXXIV—The Quadroon’s Story

CHAPTER XXXV—The Tokens

CHAPTER XXXVI—Emmeline and Cassy

CHAPTER XXXVII—Liberty

CHAPTER XXXVIII—The Victory

CHAPTER XXXIX—The Stratagem

CHAPTER XL—The Martyr

CHAPTER XLI—The Young Master

CHAPTER XLII—An Authentic Ghost Story

CHAPTER XLIII—Results

CHAPTER XLIV—The Liberator

CHAPTER XLV—Concluding Remarks

List of Illustrations

Eliza comes to tell Uncle Tom that he is sold, and that she is running away to

save her child.

THE AUCTION SALE.

THE FREEMAN’S DEFENCE.

LITTLE EVA READING THE BIBLE TO UNCLE TOM IN THE ARBOR.

CASSY MINISTERING TO UNCLE TOM AFTER HIS WHIPPING.

THE FUGITIVES ARE SAVE IN A FREE LAND.

VOLUME I

CHAPTER I

In Which the Reader Is Introduced to a Man of Humanity

Late in the afternoon of a chilly day in February, two gentlemen were sitting

alone over their wine, in a well-furnished dining parlor, in the town of P——, in

Kentucky. There were no servants present, and the gentlemen, with chairs

closely approaching, seemed to be discussing some subject with great

earnestness.

For convenience sake, we have said, hitherto, two gentlemen. One of the parties, however, when critically examined, did not seem, strictly speaking, to come under the species. He was a short, thick-set man, with coarse,

commonplace features, and that swaggering air of pretension which marks a low

man who is trying to elbow his way upward in the world. He was much over-dressed, in a gaudy vest of many colors, a blue neckerchief, bedropped gayly with yellow spots, and arranged with a flaunting tie, quite in keeping with the general air of the man. His hands, large and coarse, were plentifully bedecked with rings; and he wore a heavy gold watch-chain, with a bundle of seals of portentous size, and a great variety of colors, attached to it,—which, in the ardor

of conversation, he was in the habit of flourishing and jingling with evident satisfaction. His conversation was in free and easy defiance of Murray’s

Grammar,[1] and was garnished at convenient intervals with various profane expressions, which not even the desire to be graphic in our account shall induce

us to transcribe.

[1] English Grammar (1795), by Lindley Murray (1745-1826), the most authoritative American grammarian of his day.

His companion, Mr. Shelby, had the appearance of a gentleman; and the

arrangements of the house, and the general air of the housekeeping, indicated easy, and even opulent circumstances. As we before stated, the two were in the

midst of an earnest conversation.

“That is the way I should arrange the matter,” said Mr. Shelby.

“I can’t make trade that way—I positively can’t, Mr. Shelby,” said the other,

holding up a glass of wine between his eye and the light.

“Why, the fact is, Haley, Tom is an uncommon fellow; he is certainly worth that sum anywhere,—steady, honest, capable, manages my whole farm like a

clock.”

“You mean honest, as niggers go,” said Haley, helping himself to a glass of brandy.

“No; I mean, really, Tom is a good, steady, sensible, pious fellow. He got religion at a camp-meeting, four years ago; and I believe he really did get it. I’ve trusted him, since then, with everything I have,—money, house, horses,—and let

him come and go round the country; and I always found him true and square in

everything.”

“Some folks don’t believe there is pious niggers Shelby,” said Haley, with a candid flourish of his hand, “but I do. I had a fellow, now, in this yer last lot I took to Orleans—‘t was as good as a meetin, now, really, to hear that critter pray;

and he was quite gentle and quiet like. He fetched me a good sum, too, for I bought him cheap of a man that was ’bliged to sell out; so I realized six hundred

on him. Yes, I consider religion a valeyable thing in a nigger, when it’s the genuine article, and no mistake.”

“Well, Tom’s got the real article, if ever a fellow had,” rejoined the other.

“Why, last fall, I let him go to Cincinnati alone, to do business for me, and bring

home five hundred dollars. ‘Tom,’ says I to him, ‘I trust you, because I think you’re a Christian—I know you wouldn’t cheat.’ Tom comes back, sure enough;

I knew he would. Some low fellows, they say, said to him—Tom, why don’t you

make tracks for Canada?’ ’Ah, master trusted me, and I couldn’t,’—they told me

about it. I am sorry to part with Tom, I must say. You ought to let him cover the

whole balance of the debt; and you would, Haley, if you had any conscience.”

“Well, I’ve got just as much conscience as any man in business can afford to

keep,—just a little, you know, to swear by, as ’t were,” said the trader, jocularly;

“and, then, I’m ready to do anything in reason to ’blige friends; but this yer, you

see, is a leetle too hard on a fellow—a leetle too hard.” The trader sighed contemplatively, and poured out some more brandy.

“Well, then, Haley, how will you trade?” said Mr. Shelby, after an uneasy

interval of silence.

“Well, haven’t you a boy or gal that you could throw in with Tom?”

“Hum!—none that I could well spare; to tell the truth, it’s only hard necessity

makes me willing to sell at all. I don’t like parting with any of my hands, that’s a

fact.”

Here the door opened, and a small quadroon boy, between four and five years

of age, entered the room. There was something in his appearance remarkably beautiful and engaging. His black hair, fine as floss silk, hung in glossy curls about his round, dimpled face, while a pair of large dark eyes, full of fire and softness, looked out from beneath the rich, long lashes, as he peered curiously into the apartment. A gay robe of scarlet and yellow plaid, carefully made and neatly fitted, set off to advantage the dark and rich style of his beauty; and a certain comic air of assurance, blended with bashfulness, showed that he had been not unused to being petted and noticed by his master.

“Hulloa, Jim Crow!” said Mr. Shelby, whistling, and snapping a bunch of

raisins towards him, “pick that up, now!”

The child scampered, with all his little strength, after the prize, while his master laughed.

“Come here, Jim Crow,” said he. The child came up, and the master patted the

curly head, and chucked him under the chin.

“Now, Jim, show this gentleman how you can dance and sing.” The boy

commenced one of those wild, grotesque songs common among the negroes, in a

rich, clear voice, accompanying his singing with many comic evolutions of the

hands, feet, and whole body, all in perfect time to the music.

“Bravo!” said Haley, throwing him a quarter of an orange.

“Now, Jim, walk like old Uncle Cudjoe, when he has the rheumatism,” said

his master.

Instantly the flexible limbs of the child assumed the appearance of deformity

and distortion, as, with his back humped up, and his master’s stick in his hand,

he hobbled about the room, his childish face drawn into a doleful pucker, and spitting from right to left, in imitation of an old man.

Both gentlemen laughed uproariously.

“Now, Jim,” said his master, “show us how old Elder Robbins leads the

psalm.” The boy drew his chubby face down to a formidable length, and

commenced toning a psalm tune through his nose, with imperturbable gravity.

“Hurrah! bravo! what a young ’un!” said Haley; “that chap’s a case, I’ll

promise. Tell you what,” said he, suddenly clapping his hand on Mr. Shelby’s shoulder, “fling in that chap, and I’ll settle the business—I will. Come, now, if

that ain’t doing the thing up about the rightest!”

At this moment, the door was pushed gently open, and a young quadroon

woman, apparently about twenty-five, entered the room.

There needed only a glance from the child to her, to identify her as its mother.

There was the same rich, full, dark eye, with its long lashes; the same ripples of silky black hair. The brown of her complexion gave way on the cheek to a

perceptible flush, which deepened as she saw the gaze of the strange man fixed

upon her in bold and undisguised admiration. Her dress was of the neatest

possible fit, and set off to advantage her finely moulded shape;—a delicately formed hand and a trim foot and ankle were items of appearance that did not escape the quick eye of the trader, well used to run up at a glance the points of a

fine female article.

“Well, Eliza?” said her master, as she stopped and looked hesitatingly at him.

“I was looking for Harry, please, sir;” and the boy bounded toward her,

showing his spoils, which he had gathered in the skirt of his robe.

“Well, take him away then,” said Mr. Shelby; and hastily she withdrew,

carrying the child on her arm.

“By Jupiter,” said the trader, turning to him in admiration, “there’s an article,

now! You might make your fortune on that ar gal in Orleans, any day. I’ve seen

over a thousand, in my day, paid down for gals not a bit handsomer.”

“I don’t want to make my fortune on her,” said Mr. Shelby, dryly; and, seeking

to turn the conversation, he uncorked a bottle of fresh wine, and asked his companion’s opinion of it.

“Capital, sir,—first chop!” said the trader; then turning, and slapping his hand

familiarly on Shelby’s shoulder, he added—

“Come, how will you trade about the gal?—what shall I say for her—what’ll

you take?”

“Mr. Haley, she is not to be sold,” said Shelby. “My wife would not part with

her for her weight in gold.”

“Ay, ay! women always say such things, cause they ha’nt no sort of

calculation. Just show ’em how many watches, feathers, and trinkets, one’s

weight in gold would buy, and that alters the case, I reckon.”

“I tell you, Haley, this must not be spoken of; I say no, and I mean no,” said

Shelby, decidedly.

“Well, you’ll let me have the boy, though,” said the trader; “you must own I’ve come down pretty handsomely for him.”

“What on earth can you want with the child?” said Shelby.

“Why, I’ve got a friend that’s going into this yer branch of the business—

wants to buy up handsome boys to raise for the market. Fancy articles entirely—

sell for waiters, and so on, to rich ’uns, that can pay for handsome ’uns. It sets

off one of yer great places—a real handsome boy to open door, wait, and tend.

They fetch a good sum; and this little devil is such a comical, musical concern,

he’s just the article!’

“I would rather not sell him,” said Mr. Shelby, thoughtfully; “the fact is, sir, I’m a humane man, and I hate to take the boy from his mother, sir.”

“O, you do?—La! yes—something of that ar natur. I understand, perfectly. It

is mighty onpleasant getting on with women, sometimes, I al’ays hates these yer

screechin,’ screamin’ times. They are mighty onpleasant; but, as I manages business, I generally avoids ’em, sir. Now, what if you get the girl off for a day,

or a week, or so; then the thing’s done quietly,—all over before she comes home.

Your wife might get her some ear-rings, or a new gown, or some such truck, to

make up with her.”

“I’m afraid not.”

“Lor bless ye, yes! These critters ain’t like white folks, you know; they gets over things, only manage right. Now, they say,” said Haley, assuming a candid and confidential air, “that this kind o’ trade is hardening to the feelings; but I never found it so. Fact is, I never could do things up the way some fellers manage the business. I’ve seen ’em as would pull a woman’s child out of her arms, and set him up to sell, and she screechin’ like mad all the time;—very bad

policy—damages the article—makes ’em quite unfit for service sometimes. I

knew a real handsome gal once, in Orleans, as was entirely ruined by this sort o’

handling. The fellow that was trading for her didn’t want her baby; and she was

one of your real high sort, when her blood was up. I tell you, she squeezed up

her child in her arms, and talked, and went on real awful. It kinder makes my blood run cold to think of ’t; and when they carried off the child, and locked her

up, she jest went ravin’ mad, and died in a week. Clear waste, sir, of a thousand

dollars, just for want of management,—there’s where ’t is. It’s always best to do

the humane thing, sir; that’s been my experience.” And the trader leaned back in his chair, and folded his arm, with an air of virtuous decision, apparently considering himself a second Wilberforce.

The subject appeared to interest the gentleman deeply; for while Mr. Shelby

was thoughtfully peeling an orange, Haley broke out afresh, with becoming

diffidence, but as if actually driven by the force of truth to say a few words more.

“It don’t look well, now, for a feller to be praisin’ himself; but I say it jest because it’s the truth. I believe I’m reckoned to bring in about the finest droves

of niggers that is brought in,—at least, I’ve been told so; if I have once, I reckon

I have a hundred times,—all in good case,—fat and likely, and I lose as few as any man in the business. And I lays it all to my management, sir; and humanity,

sir, I may say, is the great pillar of my management.”

Mr. Shelby did not know what to say, and so he said, “Indeed!”

“Now, I’ve been laughed at for my notions, sir, and I’ve been talked to. They

an’t pop’lar, and they an’t common; but I stuck to ’em, sir; I’ve stuck to ’em, and

realized well on ’em; yes, sir, they have paid their passage, I may say,” and the

trader laughed at his joke.

There was something so piquant and original in these elucidations of

humanity, that Mr. Shelby could not help laughing in company. Perhaps you

laugh too, dear reader; but you know humanity comes out in a variety of strange

forms now-a-days, and there is no end to the odd things that humane people will

say and do.

Mr. Shelby’s laugh encouraged the trader to proceed.

“It’s strange, now, but I never could beat this into people’s heads. Now, there

was Tom Loker, my old partner, down in Natchez; he was a clever fellow, Tom

was, only the very devil with niggers,—on principle ’t was, you see, for a better

hearted feller never broke bread; ’t was his system, sir. I used to talk to Tom.

‘Why, Tom,’ I used to say, ‘when your gals takes on and cry, what’s the use o’

crackin on’ ’em over the head, and knockin’ on ’em round? It’s ridiculous,’ says

I, ‘and don’t do no sort o’ good. Why, I don’t see no harm in their cryin’,’ says I;

’it’s natur,’ says I, ‘and if natur can’t blow off one way, it will another. Besides,

Tom,’ says I, ‘it jest spiles your gals; they get sickly, and down in the mouth; and

sometimes they gets ugly,—particular yallow gals do,—and it’s the devil and all

gettin’ on ’em broke in. Now,’ says I, ‘why can’t you kinder coax ’em up, and speak ’em fair? Depend on it, Tom, a little humanity, thrown in along, goes a heap further than all your jawin’ and crackin’; and it pays better,’ says I, ‘depend

on ’t.’ But Tom couldn’t get the hang on ’t; and he spiled so many for me, that I

had to break off with him, though he was a good-hearted fellow, and as fair a business hand as is goin’.”

“And do you find your ways of managing do the business better than Tom’s?”

said Mr. Shelby.

“Why, yes, sir, I may say so. You see, when I any ways can, I takes a leetle care about the onpleasant parts, like selling young uns and that,—get the gals out

of the way—out of sight, out of mind, you know,—and when it’s clean done, and

can’t be helped, they naturally gets used to it. ’Tan’t, you know, as if it was white

folks, that’s brought up in the way of ’spectin’ to keep their children and wives,

and all that. Niggers, you know, that’s fetched up properly, ha’n’t no kind of

’spectations of no kind; so all these things comes easier.”

“I’m afraid mine are not properly brought up, then,” said Mr. Shelby.

“S’pose not; you Kentucky folks spile your niggers. You mean well by ’em,

but ’tan’t no real kindness, arter all. Now, a nigger, you see, what’s got to be hacked and tumbled round the world, and sold to Tom, and Dick, and the Lord

knows who, ’tan’t no kindness to be givin’ on him notions and expectations, and

bringin’ on him up too well, for the rough and tumble comes all the harder on him arter. Now, I venture to say, your niggers would be quite chop-fallen in a place where some of your plantation niggers would be singing and whooping

like all possessed. Every man, you know, Mr. Shelby, naturally thinks well of his

own ways; and I think I treat niggers just about as well as it’s ever worth while

to treat ’em.”

“It’s a happy thing to be satisfied,” said Mr. Shelby, with a slight shrug, and

some perceptible feelings of a disagreeable nature.

“Well,” said Haley, after they had both silently picked their nuts for a season,

“what do you say?”

“I’ll think the matter over, and talk with my wife,” said Mr. Shelby.

“Meantime, Haley, if you want the matter carried on in the quiet way you speak

of, you’d best not let your business in this neighborhood be known. It will get out among my boys, and it will not be a particularly quiet business getting away

any of my fellows, if they know it, I’ll promise you.”

“O! certainly, by all means, mum! of course. But I’ll tell you. I’m in a devil of

a hurry, and shall want to know, as soon as possible, what I may depend on,”

said he, rising and putting on his overcoat.

“Well, call up this evening, between six and seven, and you shall have my

answer,” said Mr. Shelby, and the trader bowed himself out of the apartment.

“I’d like to have been able to kick the fellow down the steps,” said he to himself, as he saw the door fairly closed, “with his impudent assurance; but he

knows how much he has me at advantage. If anybody had ever said to me that I

should sell Tom down south to one of those rascally traders, I should have said,

’Is thy servant a dog, that he should do this thing?’ And now it must come, for

aught I see. And Eliza’s child, too! I know that I shall have some fuss with wife

about that; and, for that matter, about Tom, too. So much for being in debt,—

heigho! The fellow sees his advantage, and means to push it.”

Perhaps the mildest form of the system of slavery is to be seen in the State of

Kentucky. The general prevalence of agricultural pursuits of a quiet and gradual

nature, not requiring those periodic seasons of hurry and pressure that are called for in the business of more southern districts, makes the task of the negro a more

healthful and reasonable one; while the master, content with a more gradual style

of acquisition, has not those temptations to hardheartedness which always

overcome frail human nature when the prospect of sudden and rapid gain is

weighed in the balance, with no heavier counterpoise than the interests of the helpless and unprotected.

Whoever visits some estates there, and witnesses the good-humored

indulgence of some masters and mistresses, and the affectionate loyalty of some

slaves, might be tempted to dream the oft-fabled poetic legend of a patriarchal institution, and all that; but over and above the scene there broods a portentous

shadow—the shadow of law. So long as the law considers all these human beings, with beating hearts and living affections, only as so many things belonging to a master,—so long as the failure, or misfortune, or imprudence, or

death of the kindest owner, may cause them any day to exchange a life of kind

protection and indulgence for one of hopeless misery and toil,—so long it is impossible to make anything beautiful or desirable in the best regulated

administration of slavery.

Mr. Shelby was a fair average kind of man, good-natured and kindly, and

disposed to easy indulgence of those around him, and there had never been a lack of anything which might contribute to the physical comfort of the negroes

on his estate. He had, however, speculated largely and quite loosely; had

involved himself deeply, and his notes to a large amount had come into the hands

of Haley; and this small piece of information is the key to the preceding

conversation.

Now, it had so happened that, in approaching the door, Eliza had caught

enough of the conversation to know that a trader was making offers to her master

for somebody.

She would gladly have stopped at the door to listen, as she came out; but her

mistress just then calling, she was obliged to hasten away.

Still she thought she heard the trader make an offer for her boy;—could she be

mistaken? Her heart swelled and throbbed, and she involuntarily strained him so

tight that the little fellow looked up into her face in astonishment.

“Eliza, girl, what ails you today?” said her mistress, when Eliza had upset the

wash-pitcher, knocked down the workstand, and finally was abstractedly

offering her mistress a long nightgown in place of the silk dress she had ordered

her to bring from the wardrobe.

Eliza started. “O, missis!” she said, raising her eyes; then, bursting into tears, she sat down in a chair, and began sobbing.

“Why, Eliza child, what ails you?” said her mistress.

“O! missis, missis,” said Eliza, “there’s been a trader talking with master in the parlor! I heard him.”

“Well, silly child, suppose there has.”

“O, missis, do you suppose mas’r would sell my Harry?” And the poor

creature threw herself into a chair, and sobbed convulsively.

“Sell him! No, you foolish girl! You know your master never deals with those

southern traders, and never means to sell any of his servants, as long as they behave well. Why, you silly child, who do you think would want to buy your Harry? Do you think all the world are set on him as you are, you goosie? Come,

cheer up, and hook my dress. There now, put my back hair up in that pretty braid

you learnt the other day, and don’t go listening at doors any more.”

“Well, but, missis, you never would give your consent—to—to—”

“Nonsense, child! to be sure, I shouldn’t. What do you talk so for? I would as

soon have one of my own children sold. But really, Eliza, you are getting

altogether too proud of that little fellow. A man can’t put his nose into the door,

but you think he must be coming to buy him.”

Reassured by her mistress’ confident tone, Eliza proceeded nimbly and

adroitly with her toilet, laughing at her own fears, as she proceeded.

Mrs. Shelby was a woman of high class, both intellectually and morally. To

that natural magnanimity and generosity of mind which one often marks as

characteristic of the women of Kentucky, she added high moral and religious

sensibility and principle, carried out with great energy and ability into practical

results. Her husband, who made no professions to any particular religious

character, nevertheless reverenced and respected the consistency of hers, and

stood, perhaps, a little in awe of her opinion. Certain it was that he gave her unlimited scope in all her benevolent efforts for the comfort, instruction, and improvement of her servants, though he never took any decided part in them

himself. In fact, if not exactly a believer in the doctrine of the efficiency of the

extra good works of saints, he really seemed somehow or other to fancy that his

wife had piety and benevolence enough for two—to indulge a shadowy

expectation of getting into heaven through her superabundance of qualities to which he made no particular pretension.

The heaviest load on his mind, after his conversation with the trader, lay in the

foreseen necessity of breaking to his wife the arrangement contemplated,—

meeting the importunities and opposition which he knew he should have reason

to encounter.

Mrs. Shelby, being entirely ignorant of her husband’s embarrassments, and

knowing only the general kindliness of his temper, had been quite sincere in the

entire incredulity with which she had met Eliza’s suspicions. In fact, she

dismissed the matter from her mind, without a second thought; and being

occupied in preparations for an evening visit, it passed out of her thoughts entirely.

CHAPTER II

The Mother

Eliza had been brought up by her mistress, from girlhood, as a petted and

indulged favorite.

The traveller in the south must often have remarked that peculiar air of

refinement, that softness of voice and manner, which seems in many cases to be

a particular gift to the quadroon and mulatto women. These natural graces in the

quadroon are often united with beauty of the most dazzling kind, and in almost

every case with a personal appearance prepossessing and agreeable. Eliza, such

as we have described her, is not a fancy sketch, but taken from remembrance, as

we saw her, years ago, in Kentucky. Safe under the protecting care of her

mistress, Eliza had reached maturity without those temptations which make

beauty so fatal an inheritance to a slave. She had been married to a bright and talented young mulatto man, who was a slave on a neighboring estate, and bore

the name of George Harris.

This young man had been hired out by his master to work in a bagging

factory, where his adroitness and ingenuity caused him to be considered the first

hand in the place. He had invented a machine for the cleaning of the hemp, which, considering the education and circumstances of the inventor, displayed

quite as much mechanical genius as Whitney’s cotton-gin.[1]

[2] A machine of this description was really the invention of a young colored man in Kentucky. [Mrs. Stowe’s note.]

He was possessed of a handsome person and pleasing manners, and was a

general favorite in the factory. Nevertheless, as this young man was in the eye of

the law not a man, but a thing, all these superior qualifications were subject to

the control of a vulgar, narrow-minded, tyrannical master. This same gentleman,

having heard of the fame of George’s invention, took a ride over to the factory,

to see what this intelligent chattel had been about. He was received with great enthusiasm by the employer, who congratulated him on possessing so valuable a

slave.

He was waited upon over the factory, shown the machinery by George, who,

in high spirits, talked so fluently, held himself so erect, looked so handsome and manly, that his master began to feel an uneasy consciousness of inferiority. What

business had his slave to be marching round the country, inventing machines, and holding up his head among gentlemen? He’d soon put a stop to it. He’d take

him back, and put him to hoeing and digging, and “see if he’d step about so smart.” Accordingly, the manufacturer and all hands concerned were astounded

when he suddenly demanded George’s wages, and announced his intention of

taking him home.

“But, Mr. Harris,” remonstrated the manufacturer, “isn’t this rather sudden?”

“What if it is?—isn’t the man mine?”

“We would be willing, sir, to increase the rate of compensation.”

“No object at all, sir. I don’t need to hire any of my hands out, unless I’ve a

mind to.”

“But, sir, he seems peculiarly adapted to this business.”

“Dare say he may be; never was much adapted to anything that I set him

about, I’ll be bound.”

“But only think of his inventing this machine,” interposed one of the

workmen, rather unluckily.

“O yes! a machine for saving work, is it? He’d invent that, I’ll be bound; let a

nigger alone for that, any time. They are all labor-saving machines themselves,

every one of ’em. No, he shall tramp!”

George had stood like one transfixed, at hearing his doom thus suddenly

pronounced by a power that he knew was irresistible. He folded his arms, tightly

pressed in his lips, but a whole volcano of bitter feelings burned in his bosom,

and sent streams of fire through his veins. He breathed short, and his large dark

eyes flashed like live coals; and he might have broken out into some dangerous

ebullition, had not the kindly manufacturer touched him on the arm, and said, in

a low tone,

“Give way, George; go with him for the present. We’ll try to help you, yet.”

The tyrant observed the whisper, and conjectured its import, though he could

not hear what was said; and he inwardly strengthened himself in his

determination to keep the power he possessed over his victim.

George was taken home, and put to the meanest drudgery of the farm. He had

been able to repress every disrespectful word; but the flashing eye, the gloomy

and troubled brow, were part of a natural language that could not be repressed,—

indubitable signs, which showed too plainly that the man could not become a

thing.

It was during the happy period of his employment in the factory that George

had seen and married his wife. During that period,—being much trusted and

favored by his employer,—he had free liberty to come and go at discretion. The

marriage was highly approved of by Mrs. Shelby, who, with a little womanly

complacency in match-making, felt pleased to unite her handsome favorite with

one of her own class who seemed in every way suited to her; and so they were

married in her mistress’ great parlor, and her mistress herself adorned the bride’s

beautiful hair with orange-blossoms, and threw over it the bridal veil, which certainly could scarce have rested on a fairer head; and there was no lack of white gloves, and cake and wine,—of admiring guests to praise the bride’s

beauty, and her mistress’ indulgence and liberality. For a year or two Eliza saw

her husband frequently, and there was nothing to interrupt their happiness,

except the loss of two infant children, to whom she was passionately attached, and whom she mourned with a grief so intense as to call for gentle remonstrance

from her mistress, who sought, with maternal anxiety, to direct her naturally passionate feelings within the bounds of reason and religion.

After the birth of little Harry, however, she had gradually become

tranquillized and settled; and every bleeding tie and throbbing nerve, once more

entwined with that little life, seemed to become sound and healthful, and Eliza was a happy woman up to the time that her husband was rudely torn from his kind employer, and brought under the iron sway of his legal owner.

The manufacturer, true to his word, visited Mr. Harris a week or two after George had been taken away, when, as he hoped, the heat of the occasion had passed away, and tried every possible inducement to lead him to restore him to

his former employment.

“You needn’t trouble yourself to talk any longer,” said he, doggedly; “I know

my own business, sir.”

“I did not presume to interfere with it, sir. I only thought that you might think

it for your interest to let your man to us on the terms proposed.”

“O, I understand the matter well enough. I saw your winking and whispering,

the day I took him out of the factory; but you don’t come it over me that way. It’s

a free country, sir; the man’s mine, and I do what I please with him,—that’s it!”

And so fell George’s last hope;—nothing before him but a life of toil and

drudgery, rendered more bitter by every little smarting vexation and indignity which tyrannical ingenuity could devise.

A very humane jurist once said, The worst use you can put a man to is to hang

him. No; there is another use that a man can be put to that is WORSE!

CHAPTER III

The Husband and Father

Mrs. Shelby had gone on her visit, and Eliza stood in the verandah, rather dejectedly looking after the retreating carriage, when a hand was laid on her shoulder. She turned, and a bright smile lighted up her fine eyes.

“George, is it you? How you frightened me! Well; I am so glad you ’s come!

Missis is gone to spend the afternoon; so come into my little room, and we’ll have the time all to ourselves.”

Saying this, she drew him into a neat little apartment opening on the verandah,

where she generally sat at her sewing, within call of her mistress.

“How glad I am!—why don’t you smile?—and look at Harry—how he

grows.” The boy stood shyly regarding his father through his curls, holding close

to the skirts of his mother’s dress. “Isn’t he beautiful?” said Eliza, lifting his long curls and kissing him.

“I wish he’d never been born!” said George, bitterly. “I wish I’d never been born myself!”

Surprised and frightened, Eliza sat down, leaned her head on her husband’s

shoulder, and burst into tears.

“There now, Eliza, it’s too bad for me to make you feel so, poor girl!” said he,

fondly; “it’s too bad: O, how I wish you never had seen me—you might have been happy!”

“George! George! how can you talk so? What dreadful thing has happened, or

is going to happen? I’m sure we’ve been very happy, till lately.”

“So we have, dear,” said George. Then drawing his child on his knee, he

gazed intently on his glorious dark eyes, and passed his hands through his long

curls.

“Just like you, Eliza; and you are the handsomest woman I ever saw, and the

best one I ever wish to see; but, oh, I wish I’d never seen you, nor you me!”

“O, George, how can you!”

“Yes, Eliza, it’s all misery, misery, misery! My life is bitter as wormwood; the

very life is burning out of me. I’m a poor, miserable, forlorn drudge; I shall only drag you down with me, that’s all. What’s the use of our trying to do anything,

trying to know anything, trying to be anything? What’s the use of living? I wish I

was dead!”

“O, now, dear George, that is really wicked! I know how you feel about losing

your place in the factory, and you have a hard master; but pray be patient, and

perhaps something—”

“Patient!” said he, interrupting her; “haven’t I been patient? Did I say a word

when he came and took me away, for no earthly reason, from the place where everybody was kind to me? I’d paid him truly every cent of my earnings,—and

they all say I worked well.”

“Well, it is dreadful,” said Eliza; “but, after all, he is your master, you know.”

“My master! and who made him my master? That’s what I think of—what

right has he to me? I’m a man as much as he is. I’m a better man than he is. I

know more about business than he does; I am a better manager than he is; I can

read better than he can; I can write a better hand,—and I’ve learned it all myself,

and no thanks to him,—I’ve learned it in spite of him; and now what right has he

to make a dray-horse of me?—to take me from things I can do, and do better than he can, and put me to work that any horse can do? He tries to do it; he says

he’ll bring me down and humble me, and he puts me to just the hardest, meanest

and dirtiest work, on purpose!”

“O, George! George! you frighten me! Why, I never heard you talk so; I’m

afraid you’ll do something dreadful. I don’t wonder at your feelings, at all; but

oh, do be careful—do, do—for my sake—for Harry’s!”

“I have been careful, and I have been patient, but it’s growing worse and

worse; flesh and blood can’t bear it any longer;—every chance he can get to insult and torment me, he takes. I thought I could do my work well, and keep on

quiet, and have some time to read and learn out of work hours; but the more he

sees I can do, the more he loads on. He says that though I don’t say anything, he

sees I’ve got the devil in me, and he means to bring it out; and one of these days

it will come out in a way that he won’t like, or I’m mistaken!”

“O dear! what shall we do?” said Eliza, mournfully.

“It was only yesterday,” said George, “as I was busy loading stones into a cart,

that young Mas’r Tom stood there, slashing his whip so near the horse that the

creature was frightened. I asked him to stop, as pleasant as I could,—he just kept

right on. I begged him again, and then he turned on me, and began striking me. I

held his hand, and then he screamed and kicked and ran to his father, and told

him that I was fighting him. He came in a rage, and said he’d teach me who was my master; and he tied me to a tree, and cut switches for young master, and told

him that he might whip me till he was tired;—and he did do it! If I don’t make

him remember it, some time!” and the brow of the young man grew dark, and his

eyes burned with an expression that made his young wife tremble. “Who made

this man my master? That’s what I want to know!” he said.

“Well,” said Eliza, mournfully, “I always thought that I must obey my master

and mistress, or I couldn’t be a Christian.”

“There is some sense in it, in your case; they have brought you up like a child,

fed you, clothed you, indulged you, and taught you, so that you have a good education; that is some reason why they should claim you. But I have been

kicked and cuffed and sworn at, and at the best only let alone; and what do I owe? I’ve paid for all my keeping a hundred times over. I won’t bear it. No, I won’t!” he said, clenching his hand with a fierce frown.

Eliza trembled, and was silent. She had never seen her husband in this mood

before; and her gentle system of ethics seemed to bend like a reed in the surges

of such passions.

“You know poor little Carlo, that you gave me,” added George; “the creature

has been about all the comfort that I’ve had. He has slept with me nights, and followed me around days, and kind o’ looked at me as if he understood how I felt. Well, the other day I was just feeding him with a few old scraps I picked up

by the kitchen door, and Mas’r came along, and said I was feeding him up at his

expense, and that he couldn’t afford to have every nigger keeping his dog, and

ordered me to tie a stone to his neck and throw him in the pond.”

“O, George, you didn’t do it!”

“Do it? not I!—but he did. Mas’r and Tom pelted the poor drowning creature

with stones. Poor thing! he looked at me so mournful, as if he wondered why I

didn’t save him. I had to take a flogging because I wouldn’t do it myself. I don’t

care. Mas’r will find out that I’m one that whipping won’t tame. My day will come yet, if he don’t look out.”

“What are you going to do? O, George, don’t do anything wicked; if you only

trust in God, and try to do right, he’ll deliver you.”

“I an’t a Christian like you, Eliza; my heart’s full of bitterness; I can’t trust in

God. Why does he let things be so?”

“O, George, we must have faith. Mistress says that when all things go wrong

to us, we must believe that God is doing the very best.”

“That’s easy to say for people that are sitting on their sofas and riding in their carriages; but let ’em be where I am, I guess it would come some harder. I wish I

could be good; but my heart burns, and can’t be reconciled, anyhow. You

couldn’t in my place,—you can’t now, if I tell you all I’ve got to say. You don’t

know the whole yet.”

“What can be coming now?”

“Well, lately Mas’r has been saying that he was a fool to let me marry off the

place; that he hates Mr. Shelby and all his tribe, because they are proud, and hold

their heads up above him, and that I’ve got proud notions from you; and he says

he won’t let me come here any more, and that I shall take a wife and settle down

on his place. At first he only scolded and grumbled these things; but yesterday

he told me that I should take Mina for a wife, and settle down in a cabin with her, or he would sell me down river.”

“Why—but you were married to me, by the minister, as much as if you’d been

a white man!” said Eliza, simply.

“Don’t you know a slave can’t be married? There is no law in this country for

that; I can’t hold you for my wife, if he chooses to part us. That’s why I wish I’d

never seen you,—why I wish I’d never been born; it would have been better for

us both,—it would have been better for this poor child if he had never been born.

All this may happen to him yet!”

“O, but master is so kind!”

“Yes, but who knows?—he may die—and then he may be sold to nobody

knows who. What pleasure is it that he is handsome, and smart, and bright? I tell

you, Eliza, that a sword will pierce through your soul for every good and

pleasant thing your child is or has; it will make him worth too much for you to

keep.”

The words smote heavily on Eliza’s heart; the vision of the trader came before

her eyes, and, as if some one had struck her a deadly blow, she turned pale and

gasped for breath. She looked nervously out on the verandah, where the boy, tired of the grave conversation, had retired, and where he was riding

triumphantly up and down on Mr. Shelby’s walking-stick. She would have

spoken to tell her husband her fears, but checked herself.

“No, no,—he has enough to bear, poor fellow!” she thought. “No, I won’t tell

him; besides, it an’t true; Missis never deceives us.”

“So, Eliza, my girl,” said the husband, mournfully, “bear up, now; and good-

by, for I’m going.”

“Going, George! Going where?”

“To Canada,” said he, straightening himself up; “and when I’m there, I’ll buy

you; that’s all the hope that’s left us. You have a kind master, that won’t refuse to

sell you. I’ll buy you and the boy;—God helping me, I will!”

“O, dreadful! if you should be taken?”

“I won’t be taken, Eliza; I’ll die first! I’ll be free, or I’ll die!”

“You won’t kill yourself!”

“No need of that. They will kill me, fast enough; they never will get me down

the river alive!”

“O, George, for my sake, do be careful! Don’t do anything wicked; don’t lay

hands on yourself, or anybody else! You are tempted too much—too much; but

don’t—go you must—but go carefully, prudently; pray God to help you.”

“Well, then, Eliza, hear my plan. Mas’r took it into his head to send me right

by here, with a note to Mr. Symmes, that lives a mile past. I believe he expected

I should come here to tell you what I have. It would please him, if he thought it

would aggravate ’Shelby’s folks,’ as he calls ’em. I’m going home quite

resigned, you understand, as if all was over. I’ve got some preparations made,—

and there are those that will help me; and, in the course of a week or so, I shall

be among the missing, some day. Pray for me, Eliza; perhaps the good Lord will

hear you.”

“O, pray yourself, George, and go trusting in him; then you won’t do anything

wicked.”

“Well, now, good-by,” said George, holding Eliza’s hands, and gazing into her

eyes, without moving. They stood silent; then there were last words, and sobs, and bitter weeping,—such parting as those may make whose hope to meet again

is as the spider’s web,—and the husband and wife were parted.

CHAPTER IV

An Evening in Uncle Tom’s Cabin

The cabin of Uncle Tom was a small log building, close adjoining to “the

house,” as the negro par excellence designates his master’s dwelling. In front it had a neat garden-patch, where, every summer, strawberries, raspberries, and a variety of fruits and vegetables, flourished under careful tending. The whole front of it was covered by a large scarlet bignonia and a native multiflora rose,

which, entwisting and interlacing, left scarce a vestige of the rough logs to be seen. Here, also, in summer, various brilliant annuals, such as marigolds,

petunias, four-o’clocks, found an indulgent corner in which to unfold their

splendors, and were the delight and pride of Aunt Chloe’s heart.

Let us enter the dwelling. The evening meal at the house is over, and Aunt Chloe, who presided over its preparation as head cook, has left to inferior officers in the kitchen the business of clearing away and washing dishes, and come out into her own snug territories, to “get her ole man’s supper”; therefore,

doubt not that it is her you see by the fire, presiding with anxious interest over

certain frizzling items in a stew-pan, and anon with grave consideration lifting the cover of a bake-kettle, from whence steam forth indubitable intimations of

“something good.” A round, black, shining face is hers, so glossy as to suggest

the idea that she might have been washed over with white of eggs, like one of her own tea rusks. Her whole plump countenance beams with satisfaction and

contentment from under her well-starched checked turban, bearing on it,

however, if we must confess it, a little of that tinge of self-consciousness which

becomes the first cook of the neighborhood, as Aunt Chloe was universally held

and acknowledged to be.

A cook she certainly was, in the very bone and centre of her soul. Not a chicken or turkey or duck in the barn-yard but looked grave when they saw her

approaching, and seemed evidently to be reflecting on their latter end; and

certain it was that she was always meditating on trussing, stuffing and roasting,

to a degree that was calculated to inspire terror in any reflecting fowl living. Her

corn-cake, in all its varieties of hoe-cake, dodgers, muffins, and other species too

numerous to mention, was a sublime mystery to all less practised compounders;

and she would shake her fat sides with honest pride and merriment, as she would narrate the fruitless efforts that one and another of her compeers had made to attain to her elevation.

The arrival of company at the house, the arranging of dinners and suppers “in

style,” awoke all the energies of her soul; and no sight was more welcome to her

than a pile of travelling trunks launched on the verandah, for then she foresaw fresh efforts and fresh triumphs.

Just at present, however, Aunt Chloe is looking into the bake-pan; in which congenial operation we shall leave her till we finish our picture of the cottage.

In one corner of it stood a bed, covered neatly with a snowy spread; and by the side of it was a piece of carpeting, of some considerable size. On this piece

of carpeting Aunt Chloe took her stand, as being decidedly in the upper walks of

life; and it and the bed by which it lay, and the whole corner, in fact, were treated

with distinguished consideration, and made, so far as possible, sacred from the marauding inroads and desecrations of little folks. In fact, that corner was the drawing-room of the establishment. In the other corner was a bed of much humbler pretensions, and evidently designed for use. The wall over the fireplace was adorned with some very brilliant scriptural prints, and a portrait of General

Washington, drawn and colored in a manner which would certainly have

astonished that hero, if ever he happened to meet with its like.

On a rough bench in the corner, a couple of woolly-headed boys, with

glistening black eyes and fat shining cheeks, were busy in superintending the first walking operations of the baby, which, as is usually the case, consisted in getting up on its feet, balancing a moment, and then tumbling down,—each

successive failure being violently cheered, as something decidedly clever.

A table, somewhat rheumatic in its limbs, was drawn out in front of the fire,

and covered with a cloth, displaying cups and saucers of a decidedly brilliant pattern, with other symptoms of an approaching meal. At this table was seated Uncle Tom, Mr. Shelby’s best hand, who, as he is to be the hero of our story, we

must daguerreotype for our readers. He was a large, broad-chested, powerfully-

made man, of a full glossy black, and a face whose truly African features were

characterized by an expression of grave and steady good sense, united with

much kindliness and benevolence. There was something about his whole air self-

respecting and dignified, yet united with a confiding and humble simplicity.

He was very busily intent at this moment on a slate lying before him, on

which he was carefully and slowly endeavoring to accomplish a copy of some

letters, in which operation he was overlooked by young Mas’r George, a smart,

bright boy of thirteen, who appeared fully to realize the dignity of his position as instructor.

“Not that way, Uncle Tom,—not that way,” said he, briskly, as Uncle Tom

laboriously brought up the tail of his g the wrong side out; “that makes a q, you see.”

“La sakes, now, does it?” said Uncle Tom, looking with a respectful, admiring

air, as his young teacher flourishingly scrawled q’s and g’s innumerable for his edification; and then, taking the pencil in his big, heavy fingers, he patiently recommenced.

“How easy white folks al’us does things!” said Aunt Chloe, pausing while she

was greasing a griddle with a scrap of bacon on her fork, and regarding young

Master George with pride. “The way he can write, now! and read, too! and then

to come out here evenings and read his lessons to us,—it’s mighty interestin’!”