9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

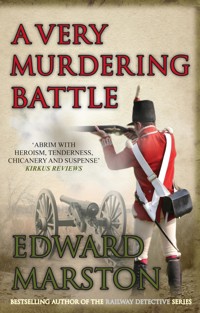

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: Captain Rawson

- Sprache: Englisch

SOLDIER OF FORTUNE CAPTAIN DANIEL RAWSON FACES HIS TOUGHEST BATTLE YET Despite winning a resounding victory at the battle of Oudenarde, the Duke of Marlborough finds his position as captain-general threatened by political enemies back in England, and his campaign to strike deeper into French Flanders is stalled at the siege of Lille, the 'pearl of fortresses'. To help facilitate the new Allied strategy, Captain Daniel Rawson is given the treacherous task of entering Lille undercover to steal vital plans. Meanwhile, in England, Daniel's beloved Amalia is herself under siege - a dangerous admirer is determined to have her, even if he has to have Daniel murdered first. As the weather worsens and Lille's famed defences appear to be holding, Daniel has to fight against one of his own allies, dwindling supplies, weakening morale, French patrols and a hired assassin. He must battle bravely on or risk losing everything . . .

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 452

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Under Siege

EDWARD MARSTON

To our lovely new granddaughter, Imogen Rose, in the hope that she will one day read it.

Contents

Title PageDedicationCHAPTER ONECHAPTER TWOCHAPTER THREECHAPTER FOURCHAPTER FIVECHAPTER SIXCHAPTER SEVENCHAPTER EIGHTCHAPTER NINECHAPTER TENCHAPTER ELEVENCHAPTER TWELVECHAPTER THIRTEENCHAPTER FOURTEENCHAPTER FIFTEENAdvertisementAbout the AuthorBy Edward MarstonCopyright

CHAPTER ONE

July,1708

‘Will you think of me, Daniel?’ she asked, gripping his hands.

‘Every day,’ he replied.

‘Will you write to me?’

‘I’ll try to, Amalia, but it’s not always possible.’

‘Promise me that you’ll take care to stay out of danger.’

He laughed. ‘That’s something I can never guarantee.’

‘I worry about you so much.’

‘There’s no need. I can look after myself.’

She tightened her grip. ‘Oh, why do you have to be a soldier?’

‘I like the life.’

‘How can you like all that pain and suffering and death?’

‘Army life has its redeeming features,’ he said with a smile. ‘Remember that it’s only because I’m a soldier that I had the opportunity to meet you. Do you have any regrets about that?’

She beamed at him. ‘No, Daniel,’ she said, ‘I don’t.’

Daniel Rawson’s visit to Amsterdam was necessarily a fleeting one. Having ridden to The Hague to deliver news of another startling victory by the Grand Alliance, he galloped north to pay the briefest of visits to Amalia Janssen. Delighted to hear of the success at the battle of Oudenarde, she was even more thrilled to see the man she loved. The seemingly endless war against the French had drawn them closer that summer because Amalia had been kidnapped by the enemy and was only rescued from their hands by Daniel’s skill and audacity. The experience had strengthened the bond between them to the point where it was unbreakable. They now lived for each other.

Duty, however, could not be ignored. The doting swain had to remind himself that he was also a captain in the 24th Regiment of Foot and a member of the Duke of Marlborough’s personal staff. He was needed by the captain-general both as an interpreter and as someone entrusted with assignments that always flirted with dire peril. A final kiss from Amalia had sent him on his way and the exquisite taste of her lips stayed with him for a whole day. He’d first met her in Paris where he’d been sent to rescue her father, Emanuel Janssen, a celebrated tapestry maker imprisoned in the Bastille when unmasked as a spy. To get them safely back to their own country, Daniel had had to call on all of his daring and resourcefulness. During the hectic flight, he’d got to know father and daughter extremely well.

Until Amalia came into his life, Daniel had taken his pleasures where he found them and broken more than a few hearts in the process. Tall, slim, well featured and with an easy charm, he’d had no shortage of conquests and took them in his stride. All that had now changed. He’d at last found a woman he adored and to whom he felt obliged to be faithful. The notion of permanence had entered his head. He’d started to think seriously about marriage, children and family life. Nevertheless, tempting as they were, such delights would have to wait until the War of the Spanish Succession eventually came to an end, and nobody could predict with any certainty when that might be. He and Amalia would have to wait, enduring the loneliness and anguish of being apart.

It was a long ride back to Oudenarde and Daniel was grateful that, for the bulk of the journey, he would have the company of a squadron of Dutch dragoons sent as reinforcements. He joined them as they were crossing the border into Flanders, his bright red coat in striking contrast to their sober grey uniforms. Daniel fell in beside a lieutenant who was intrigued by the newcomer’s history.

‘You live in Amsterdam yet fight for the British?’ he asked.

‘My father was English, my mother was Dutch.’

‘Then our army should have taken precedence. After all, you were brought up in the United Provinces. You left England when you were still a boy.’

‘I’m content to fight with a British regiment,’ said Daniel.

‘Well, you’ve obviously fought well, my friend, if you’ve earned a position alongside the captain-general himself. Tell me,’ he went on with a sly grin, ‘is it true that the Duke of Marlborough is as miserly as they say?’

‘His Grace is the most generous-hearted man I know.’

‘I speak not of his heart but of his purse. The rumour is that he keeps it shut tight. While our generals maintain their quarters in some style, the duke’s, I gather, are unbefitting a man of his standing. It’s the reason he tries to dine elsewhere instead of inviting guests to his own table.’ He gave a chuckle. ‘Why deny it? Everyone has heard about his reputation for meanness.’

‘Then everyone has heard a foul calumny,’ said Daniel, loyally. ‘I’ve had the privilege of dining in His Grace’s quarters on more than one occasion and he is an unstinting host.’

It was not entirely true but he said it with sufficient conviction to wipe the smirk off his companion’s face. In fact, Daniel knew that the idle gossip about Marlborough’s parsimony was not without foundation. By comparison with those of generals in allied armies, Marlborough’s quarters were remarkably modest and he did dine in more comfortable surroundings whenever an invitation came. Daniel would never admit that to the lieutenant. He revered the captain-general as a man and as a soldier, believing that what he did with his money was his own business. Any criticism of his mentor would always be roundly contradicted by Daniel.

‘What happens next?’ asked the lieutenant.

‘That remains to be decided.’

‘Come now, Captain Rawson. You belong to the duke’s staff. You know the way that his mind works and must have heard him discussing the possibilities that confront us. What course of action will he pursue?’

‘I have no idea,’ said Daniel, firmly.

‘I find that hard to believe.’

‘You can believe or disbelieve what you wish, Lieutenant. I have no knowledge of which way the wind blows, and even if I did, I’d never confide in someone who has such a distorted view of His Grace’s character. One of his great virtues is his ability to keep secrets. Look in his face and you will have no idea what he is thinking. In short,’ added Daniel, ‘he is discretion personified.’

The lieutenant was peeved. ‘I see that you take after him.’

‘I can imagine nobody better on whom to pattern myself.’

‘You’re speaking as an Englishman now.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘With all respect, Captain Rawson,’ said the other, sharply, ‘I think that you ought to march under a Dutch flag from time to time. Then you’d realise that the duke is not the paragon you claim.’

‘There’s no better general on this earth,’ affirmed Daniel.

‘Oh, I agree, my friend. I just wish that he’d be as ready to spill British blood as he is to shed that of the Dutch. You only have to look at Blenheim. Yes, it was a famous victory but it came at a terrible price – and it was your fellow countrymen who paid most of it.’

‘Casualties are inevitable in battle.’

‘It just happens that we had more of them than the British.’

‘Our regiments had their share of losses,’ said Daniel, stoutly. ‘I was there. I saw the carnage. Our soldiers fell all around me. Besides, if it’s a question of counting the corpses, I think that you’ll find the troops under Prince Eugene sustained the highest number of casualties. Such figures, of course, were dwarfed by French losses. Some 20,000 Frenchmen were killed or wounded and many more deserted. You should be proud that so many Dutch regiments helped to achieve that victory.’ Controlling his temper, he eyed the man coldly. ‘Do you have any other ill-informed observations to make about His Grace?’

The lieutenant lapsed into a sullen silence. They rode on for another mile before he picked up the conversation again.

‘My brother was killed at Blenheim,’ said the man, sourly.

Daniel was sympathetic. ‘I’m sorry to hear that.’

‘He was shot during the first attack.’

‘You can at least console yourself with the thought that he didn’t sacrifice his life in vain. Your brother was part of an army that inflicted lasting humiliation on the French.’

The man was scornful. ‘What bloody use is that?’ he challenged. ‘Humiliation didn’t bring about surrender. We trounced the French at Blenheim, at Ramillies and now at Oudenarde but they still keep coming back at us. This damnable war drags on from year to year.’

‘Granted,’ said Daniel, ‘but they fight with a debilitated army now. We have the upper hand and they know it. It’s the reason their diplomats sue for peace so strenuously behind the scenes.’

‘Then why is there no end to it all?’

‘Because the terms they offer are unacceptable.’

‘We have your precious Duke of Marlborough to thank for that,’ alleged the other. ‘Left to us, there’d have been an honourable peace treaty long before now.’

‘There’d also be a Frenchman on the throne of Spain,’ Daniel reminded him. ‘That’s what this war is all about. Do you really want King Louis to control the Spanish Empire and hold sway over the whole of Europe? Is that what you call an honourable peace? Or, to put it another way,’ he added, ‘did your brother, and the thousands like him, die for nothing?’

The man retreated into silence once more, cowed by Daniel’s forthrightness but unconvinced by his argument. The lieutenant’s desperation for peace was shared by many in the armies comprising the Grand Alliance. Wearied by fighting, shocked at the high death toll, frightened by the spiralling financial losses and robbed of any urge to press on, they were eager to negotiate a peace. Daniel knew full well that Marlborough was equally keen to see an end to the hostilities but neither he – nor the British government – could stomach the idea of leaving Louis XIV’s grandson, Philip, Duke of Anjou, as the ruling Spanish monarch.

‘No Peace Without Spain’ – it had been the rallying cry from the start. As other voices grew faint, that of Marlborough – and that of Captain Daniel Rawson – remained as loud as ever. Until the French claim to the Spanish throne was renounced, there was no hope at all of peace. War would continue with undiminished ferocity. As the cavalcade rode on through the sunlit countryside, Daniel wondered how long it would be before the two sides would clash once more.

Travelling with the dragoons might give him companionship and ensure his safety but it also slowed Daniel down. On the last day, therefore, he bade farewell to the squadron and set off on his own. While the others kept to the main road, he was able to veer off it and cut miles off the journey. He was riding through familiar territory, passing towns and villages that the Confederate army had liberated, lost to the French, then recaptured once more. Vestigial signs of warfare were everywhere. He passed a windmill destroyed by fire, farms deprived of their livestock and fields churned up by the furious charges of cavalry regiments. All was tranquil now but it would not be long before further havoc was wreaked.

Daniel was skirting a wood when he heard the cry. It was a long, high-pitched scream of rage from the mouth of a woman in obvious distress. Kicking his horse into a gallop, Daniel came around the angle of the trees to be confronted by a strange sight. A man in the uniform of a Hessian officer was struggling to overpower a stout woman in rough clothing. Beside them were two horses and a donkey. No quarter was given in the fight. While the woman kicked, punched, bit and unleashed a torrent of expletives, the man pummelled away at her before managing to trip her up. As she fell to the ground, he dived on top of her, holding down both of her arms in an attempt to subdue her. Spitting in his face, she tried to throw him off but he was too strong and determined. When he punched her on the jaw, she was momentarily dazed and unable to stop him hauling up her skirt to reveal a pair of fleshy thighs. Before he could lower his breeches, however, he heard the approaching horse and looked up, snarling angrily when Daniel arrived and reined in his steed.

‘Go on your way!’ he ordered.

‘It seems that I’m needed here,’ said Daniel, dismounting.

‘Stay out of this or you’ll be sorry.’

‘Leave the lady alone.’

Grabbing him by the scruff of his neck, Daniel yanked him clear of the woman then lifted him to his feet. The man swung a wild fist but Daniel parried it with an arm and replied with a relay of punches that made his adversary stagger back, blood cascading from his nose. Howling in pain, the man hurled himself at Daniel and they grappled for minutes, testing their strength, feeling for advantage, each trying to throw the other to the ground. Daniel slowly exerted pressure until he felt the Hessian weaken. Without warning, he suddenly brought his knee up into the man’s groin, causing him to bend invitingly over and allow Daniel to fell him with a solid uppercut to the chin.

As the Hessian collapsed in a heap, the woman jumped up, pulled down her skirt and started to kick the fallen man as hard as she could. Taking her by the shoulders, Daniel eased her gently away.

‘You saw what the bastard was trying to do to me!’ she yelled.

‘I want to know why,’ said Daniel.

‘He’s a cheat and a liar. He promised to buy the horse off me then refused to pay. When I argued with him, he knocked me down and tried to rape me.’ Realising that she hadn’t even thanked him, she produced a warm smile. ‘You came along at the right moment, sir. I’m very grateful to you. Where did you learn to speak German so well? There are not many British officers who can do that.’

‘I speak Dutch, French and German,’ he told her, ‘and I sometimes act as an interpreter.’

‘What about Welsh?’

He grinned. ‘That’s beyond me, I’m afraid.’

‘It’s a beautiful language. I could teach you, if you wish.’

‘No, thank you.’

‘May I know your name, please?’

‘It’s Captain Daniel Rawson.’

‘I’m Rachel Rees,’ she said with a lilt. ‘I used to be Mrs Baggott, but my first husband – God bless the old fool! – got himself stabbed to death by a French bayonet. My second husband – I was Mrs Granger when I was married to him – was trampled to death at Ramillies. By the time I found the poor dab afterwards, his head had been smashed to a pulp. I only recognised him because of the wedding ring he wore in his ear. Ah well!’ she sighed. ‘Such are the fortunes of war.’ Her brave smile was tinged with resignation. ‘Since then, I’ve used my maiden name. I’ve been plain Rachel Rees and had to shift for myself.’

She was a woman of generous proportions and middle height, with a chubby prettiness not entirely obliterated by the ravages of an outdoor life and the imprint of marital tragedy. Daniel put her in her late thirties. He didn’t need to be told what she did. Rachel Rees was a camp follower, one of the many females who trailed behind an army, acting as cooks, seamstresses, washerwomen and – in the wake of any fighting – as nurses. Clearly, she was also a scavenger, combing the battlefield after the slaughter had ceased and stripping the corpses of anything of value. Among her recent acquisitions, it appeared, was the horse now cropping the grass behind them. Daniel noted the quality of the saddle and the elaborate housing.

‘This is a French officer’s horse,’ he observed.

‘I found it looking for a new owner,’ she said, airily, ‘so I took care of it until I could sell it. This man offered me the best price,’ she went on, indicating the Hessian who was now sitting up and rubbing his sore chin, ‘and I was stupid enough to trust him. Well, you saw how he honours a bargain.’

‘She’s a horse thief!’ said the man as he hauled himself gingerly to his feet. ‘She deserves to be hanged from the nearest tree – if you can find one strong enough to support her.’

‘What’s that villain saying about me?’ demanded Rachel.

‘The lady deserves to be treated with respect,’ said Daniel in fluent German. ‘An apology would not come amiss.’

‘Apologise to that big, fat, ugly tub of lard?’ sneered the man. ‘Nothing would make me do that!’

‘Then you’ll have to die unrepentant.’

Stepping back, Daniel drew his sword with a flourish and held the point against the man’s throat, jabbing lightly to draw blood. The Hessian put a hand up to the scratch and swore volubly.

‘Hold your tongue!’ roared Rachel. ‘There’s no need for foul language. I know enough German to understand those vile words.’

‘That means you have two things for which to apologise,’ said Daniel, calmly. ‘You must say sorry for assaulting the lady and ask her pardon for inadvertently swearing in her presence. Well?’ He held out his sword. ‘Which is it to be? You can either behave like a gentleman for once or be killed like the cheating rogue you are.’

The man hesitated, weighing up his chances. His sword lay on the ground. Daniel gestured towards it, encouraging him to pick it up. If he was to kill the man, he’d do so in a fair fight. But the Hessian had grave doubts that he could get the better of his opponent if they fought on equal terms. Daniel was fit, confident and had already demonstrated his superior strength and agility. The Hessian’s one chance of winning was to shoot him with the pistol holstered beside the saddle of his horse. Pretending to bend down to retrieve his weapon, therefore, the man made a sudden dash for his horse. He was far too slow. Daniel had read his mind and stuck out a foot to send him tumbling to the ground. When the man rolled over on his back, he looked up at the sword that was poised to strike him.

‘No, no!’ he begged, losing his nerve completely. ‘Don’t kill me. I’m sorry that I attacked the lady and sorry that I swore in front of her. I apologise unreservedly. Look,’ he went on, piteously, ‘I’ll pay her twice the price she asked for the horse and we’ll part as friends.’ He turned to her. ‘What do you say to that?’

Rachel was unimpressed. ‘I wouldn’t sell it to you if you were the last man on earth,’ she said, curling a derisive lip. She held out her hand. ‘Give me the sword, Captain Rawson and let me kill him.’

‘Don’t let her touch me!’ wailed the man.

‘She won’t need to now that the apology has been made,’ said Daniel, lowering his weapon. ‘Get up and go back to your regiment in disgrace.’

‘He should pay for what he did to me!’ shouted Rachel.

‘Oh, he will – have no fear of that. The tables have been turned. He came to get a horse but will instead give one away.’

‘You can’t take my horse,’ pleaded the man, scrambling to his feet. ‘How will I get back to camp? It’s miles away.’

‘Then you’d better start walking.’

‘I’m a cavalry officer. I must have a horse.’

‘Buy one honestly,’ said Daniel, using the flat of his sword to smack the man’s buttocks. ‘Off you go!’

With a yelp of pain, the Hessian scurried away, flinging abuse over his shoulder and vowing revenge. Daniel didn’t even bother to listen. Instead, he sheathed his sword and indicated the man’s horse.

‘It’s small recompense for the way he treated you,’ he said, ‘but it’s yours to sell along with the other now. They’re both fine animals and will each cost a pretty penny.’

‘I can’t thank you enough, sir,’ said Rachel. ‘When I’ve sold the pair of them, I’ll have enough money to pay off all my debts and eat properly for a while.’ She nodded at her donkey’s huge saddlebags. ‘And I’ll be able to buy more stock. That’s how I make ends meet, you see. I’m a sutler. I sell all sorts of things to the army.’ Her face clouded for a moment. ‘Don’t think too harshly of me, Captain Rawson.’

‘Why should I do that?’ he asked. ‘I admire you. When I came along, you were putting up a good fight against that man.’

‘I know what people think about looters. They despise us for picking the pockets of the dead. But that’s not what I do. I search for the living, not the deceased. I got to Will Baggott in time to hold him in my arms for a few minutes before he passed away. It was such a comfort to him. And I’ve done it to so many other brave boys,’ she said, wistfully. ‘They’ve been given up as dead and I nurse them back to life for a while so that they can have a woman’s arms around them as they slip away. I’m there to give succour. I’m not like the others, Captain,’ she went on, earnestly. ‘I never take their money – not if they’re British soldiers.’ Her voice hardened. ‘When it comes to the French, of course, it’s a different matter. It was them who killed my two husbands and left me to fend for myself. They owe me something in return. I’m entitled to take whatever I can from them. After the battle at Oudenarde, it just happened to be that horse.’

‘Be more careful when you sell it next time,’ he advised. ‘And try one of our own regiments. At least you’ll be able to haggle in your own language then.’

‘You don’t disapprove of me, then?’ she asked, hopefully.

‘Of course not, Rachel – I’m sure that you deserve everything you find, especially as it comes with the compliments of the enemy.’ They shared a laugh. ‘I’m just grateful that I was riding this way at the right time.’

‘I’m more than grateful,’ she said, standing on her toes so that she could plant a wet kiss on his lips. ‘Thank you, sir. I’ll never forget this. You have a lifelong friend in Rachel Rees.’

‘I’m glad to hear it,’ he said, taken aback by her unexpected surge of affection. ‘In times of war, a soldier can never have too many friends. But a new friendship was not all I forged today, I fancy.’ He turned to look at the receding figure of the Hessian officer. ‘I think I may have made a sworn enemy as well.’

CHAPTER TWO

It was a brilliant plan. Conceived with care and explained in detail, it had the boldness, simplicity and originality characteristic of him. As he addressed the council of war, the Duke of Marlborough was given a respectful hearing. Daniel was there to act as an interpreter and he could see the looks of surprise – not to say amazement – on the faces of some of the Allied generals.

‘In essence,’ said Marlborough, indicating the map on the table before them, ‘we strike where they least expect us, and that is deep into France itself. We should ignore their frontier fortresses, enter the heartland and move eventually towards Paris itself. Just imagine the panic an attack on the French capital would cause. Yes,’ he went on, raising a palm to quell protests, ‘I know what the objection is. How will we maintain supplies? The answer, gentlemen, is this. A seaborne force already assembled will seize the port of Abbeville and that will be the base for our supply line.’ He saw the doubt in their faces. ‘We are masters of marching where we please. Why ignore such a huge advantage?’

‘We may march where we please,’ argued a Dutch general, ‘but we’ll not reduce French strongholds as we please, because we have no siege train. Nor are we able to transport one to the frontier by means of canals and rivers. The French still hold Ghent at the junction of the Lys and the Schelde. Vendôme and his army are skulking there and will block any attempts we make to move artillery by water.’

‘Then we bring the siege train overland,’ said Marlborough. ‘We are not unprepared, gentlemen. I’ve already sent cavalry into northern France to gather supplies and seize cattle and horses. The British navy stands by to await orders. I hardly need remind you that my brother, Admiral George Churchill, is in charge of naval operations, so we may expect complete cooperation. Well,’ he continued, spreading his arms, ‘what do you think? There are dangers, I grant you, but they are substantially lessened if we strike while the iron is hot and catch the French off guard.’ He turned to Prince Eugene of Savoy, sitting close to him. ‘What comments would you make, Your Highness?’

Pursing his lips, Eugene weighed his words before replying.

‘I congratulate you, Your Grace,’ he said, politely. ‘It is a clever and courageous plan and nobody but you could have devised it. However, I fear that it is too impracticable. We cannot venture into France until we have Lille as a place d’armes and magazine. Once that is secure, we will be in a far stronger position. Exciting as it may be, your plan involves too big a risk.’

‘I disagree,’ said Marlborough. ‘On the surface, it may look wild and overambitious but that’s all part of the deception. The French will never dream that we’d commit ourselves to an invasion on such a scale, so they will have taken no steps to counter it.’

‘I think perhaps that you should call to mind the Swedish army. They showed great daring when they took on a foe like Russia. And what has happened?’

‘They are worn out by hunger and fatigue.’

‘And hindered by constant ambushes,’ said Eugene. ‘As a result, King Charles and his army are struggling.’

‘We don’t face a parallel situation,’ contended Marlborough. ‘There are similarities, I confess, but they are few in number. We can learn from the mistakes that King Charles made. I visited him last year and saw for myself his army’s shortcomings.’

‘It had no hospitals, no magazines, no food supplies and no reinforcements close at hand. It is an army that lives on what it finds, fighting a war of chicane that is bound to end in defeat. The Russians will use delay and evasion to frustrate them,’ said Eugene, ‘and that is the strategy the French would employ against us.’

‘Not if we disable them by the suddenness of our attack.’

‘I am sorry, Your Grace, but I lack your confidence in the reliability of supplies by sea. We might seize Abbeville or any other port, but think of the problems the vessels would encounter during winter. Some would surely founder and others would be uncertain to reach us during the gales they are bound to encounter.’ Eugene placed a finger on the map. ‘This is where we must start,’ he said, collecting murmurs of approval and nods of affirmation from around the table. ‘We must lay siege to Lille.’

‘But that’s precisely what they expect,’ said Marlborough. ‘According to our latest reports, Marshal Boufflers will be sent there with a sizeable force, and nobody is more experienced at defending a town than the marshal. If we invest Lille, we are in for a long, bitter siege that will be fiendishly expensive and cost us thousands of lives we can ill afford to lose.’

‘Nevertheless, I believe it to be our next logical step.’

‘I concur with His Highness,’ said a Dutch voice. ‘Lille is second in importance only to Paris. It’s a pearl among fortresses. Take that and we’ll send a shiver down the spine of King Louis himself. No matter how long it takes, we must invest Lille.’

There was general agreement around the table. When Daniel had finished translating from the Dutch for Marlborough’s benefit, he caught the eye of Adam Cardonnel, secretary to the captain-general. Cardonnel was as disappointed as Daniel. Both of them thought the plan was an example of tactical genius yet it had been rejected out of hand. It was galling. Daniel accepted that the project was a gamble but, if it succeeded, it would surely hasten the end of the war. He’d been fired by the idea of invading France itself, sweeping all resistance aside and forcing Louis XIV to accept peace on Allied terms. It was not to be. While Daniel and Cardonnel concealed their resentment at the way the plan had been discarded, Marlborough started eagerly to discuss the siege of Lille as if that had been his intention all along. As always, he remained unfailingly courteous to those who’d wrecked yet another of his brilliant schemes.

It was only after the council of war ended, and its members had dispersed, that he let his true feelings show. Snatching up the map, he folded it angrily then slapped it back down on the table.

‘Hell and damnation!’ he exclaimed. ‘Don’t they want us to win this confounded war? Abide by my counsel and we at least have a chance of doing that. Follow their advice and we prolong the hostilities indefinitely. Laying siege to Lille could take us well into winter.’

‘It was ever thus, Your Grace,’ said Cardonnel, wearily. ‘Every time you advocate real enterprise, they retreat into their shells like so many tortoises. It’s exasperating.’ He glanced apologetically at Daniel. ‘Forgive me for casting aspersions on your fellow countrymen, but the Dutch are the real thorn in our sides.’

‘I know it only too well,’ said Daniel. ‘They are far too cautious. I expected them to take fright at such an audacious scheme but I hoped it might win support from Prince Eugene.’

‘So did I,’ resumed Marlborough, running a hand across a worried brow. ‘I have to admit that I was counting on his support. He commands great influence and is an intrepid commander. I thought my plan might appeal to his sense of adventure.’

‘Unfortunately,’ said Cardonnel, ‘he found it too adventurous.’

‘You can never be too adventurous in war, Adam.’

‘After all this time, they should trust your instincts, Your Grace. You presented them with triumphs at Blenheim, Ramillies and, only weeks ago, at Oudenarde. What more proof do they require of your unrivalled abilities in conducting a campaign?’

Marlborough heaved a sigh. ‘I wish I knew!’

‘I think I can explain Prince Eugene’s position,’ suggested Daniel. ‘Alone of those present, he recognised the virtues of striking into France. What worried him was the role of the navy. He’s accustomed to fighting land battles and has a natural distrust of amphibious warfare. The prince has some justification for his scepticism,’ he said. ‘Our sailors haven’t had an unblemished record of success so far. Look at the way we failed to take the naval base at Toulon last year, for instance. That was a serious setback.’

‘I still believe the project would have been feasible,’ said Marlborough, sadly. ‘Our cavalry met with little resistance in France. They briefly occupied towns like La Bassée, Lens, St-Quentin and Péronne and even raided the suburbs of Arras.’

‘We come back to the same old problem,’ noted Cardonnel. ‘You are hampered by the constraints of leading a coalition army.’

‘Had I been commanding a force made up entirely of British regiments, we’d now be surging through France instead of committing all our resources to Lille. As for the navy, I feel sure that they’d provide more than adequate support during summer and autumn. Even as we speak, Major General Erle is moored off the Isle of Wight with eleven embarked battalions. I accept that Abbeville would not be ideal for our purposes in winter,’ admitted Marlborough, ‘but – with luck and God’s blessing – the war might not last that long. We stand a chance of bringing France to its knees before then.’

Cardonnel nodded. ‘Instead of which we must brace ourselves for yet another campaign season next year.’

‘Where on earth will I find the strength to continue?’

Marlborough emitted another long sigh. Daniel was alarmed to see him looking so tired and forlorn. At a time when he should have been exploiting the tactical initiative gained at Oudenarde, he was unable to carry his allies with him. There was no sign of his famed resilience now. He seemed old, listless and disillusioned. Daniel sought to raise his spirits.

‘There is one ray of hope, Your Grace,’ he opined.

‘I fail to see it,’ said Marlborough.

‘The French prize Lille above all their fortresses. If they see it under threat, it might provoke them into battle.’

‘I think that unlikely, Daniel.’

‘Yet it’s still a possibility.’

‘A very faint one, alas,’ said Cardonnel.

‘Adam is right,’ agreed Marlborough. ‘Bringing the French to battle is like chasing moonbeams. Well, can you blame them? Every time they step onto a battlefield, we beat them. They’re still smarting from their disaster at Oudenarde. We’ll not lure Vendôme into action and Burgundy will not wish to lose even more men. No, Daniel, we are in for yet another protracted siege. However,’ he said, trying to shake off his cares, ‘let’s not get too downhearted. Our course is set and we must follow it.’ He straightened his shoulders. ‘Let’s turn to a more pleasant subject, shall we? I take it that you found time to pay a visit to Amsterdam.’

Daniel smiled fondly. ‘I did, Your Grace.’

‘And how did you find the dear lady?’

‘Amalia was far happier to be in her home than imprisoned in the French camp. She’ll not let herself be kidnapped again.’

‘Unless the kidnapper happens to be a certain Captain Rawson, that is,’ said Cardonnel with a grin. ‘I’m afraid that Miss Janssen may not be seeing you again for some time.’

‘She understands that,’ said Daniel.

‘What about my tapestry?’ asked Marlborough. ‘Her father must have started working on it by now.’

‘It will take some time yet, Your Grace. It’s intricate work that can’t be rushed. Emanuel Janssen and his assistants each have a separate loom so that they can weave individual sections,’ explained Daniel. ‘Eventually, they’ll sew all the different pieces together. Having fought in the battle, I was privileged to help with the design. I vow that you’ll be delighted with it. Ramillies has been depicted with uncanny accuracy. It’s going to be a masterpiece.’

Emanuel Janssen was a small, skinny, stooping man with silver hair and a beard. Long years of dedication to his craft had rounded his shoulders and dimmed his eyes, obliging him to wear spectacles. Peering through them as he worked from the back of the tapestry, he studied the mirror that showed him the front. Three other looms were in action, so the workshop at the rear of his house reverberated with rhythmical clatter. Two of his assistants had to raise their voices over the noise. The third, Kees Dopff, more of an adopted son than an assistant, had been dumb from birth, but his face was so expressive that he and his employer were able to conduct conversations without resorting to words. Janssen was still sewing meticulously away when he caught sight of his daughter out of the corner of his eye. He broke off immediately, knowing that Amalia would not have interrupted him on a whim. Something of significance must have happened. He could see the glow of excitement in her cheeks

‘Let’s step outside where it’s a little quieter,’ he suggested, guiding her back into the house. ‘Now, then,’ he said when they were out of earshot of the clamour, ‘what’s going on?’

‘A letter has come for you,’ she replied, holding it out.

‘There’s nothing unusual in that, Amalia. I get letters all the time. Couldn’t this one have waited?’

‘No, Father – it’s from England.’

He took it from her. ‘Really?’

‘Look at the seal. It’s from someone of consequence.’

‘Then let’s see what someone of consequence has to say, shall we?’ Breaking the seal, he unfolded the letter then blinked in surprise. ‘It’s from Her Grace, the Duchess of Marlborough.’

‘I could tell by the feel of it that it was important.’

‘Then you can read it to me,’ he said. ‘My eyes are always a trifle blurred after hours at the loom and your command of English is far better than mine.’

‘You must thank Daniel for that. He’s encouraged me to become fluent. He’s helped me with French as well.’ She took the missive back and held it to her breast. ‘Oh, if only this had come from him!’

Short, slight and fair-headed, Amalia had an elfin beauty that had enchanted Daniel Rawson from the start. Lost momentarily in her thoughts, she forgot that her father was even there.

‘Well?’ he asked with an amused smile. ‘Do I get to hear the contents or must I read it myself?’

Amalia giggled. ‘I’m sorry, Father.’ Glancing at the opening sentence, she let out a cry of joy. ‘It’s an invitation. Since your tapestry of Ramillies is to hang in Blenheim Palace, the duchess has invited you to England to see it being built.’

‘What a wonderful treat!’

‘She warns you that the palace is far from complete but thinks you’ll find it interesting.’

‘Then I must accept the invitation,’ he decided, ‘as long as it’s extended to you as well.’

‘Oh, yes,’ said Amalia, reading on. ‘I’m mentioned by name.’

‘Let me see.’

Taking it from her for the second time, Janssen perused it with care. Amalia, meanwhile, was many days ahead of him, boarding a ship, sailing across the North Sea, setting foot in England and being driven to Oxfordshire to view the magnificent edifice awarded to the Duke of Marlborough in commemoration of his victory at the battle of Blenheim. She was enraptured. Doubts then began to creep in.

‘What will I wear?’ she asked with sudden anxiety. ‘I’ve nothing suitable in my wardrobe. And how do I behave in front of a duchess? I’ll make all sorts of terrible mistakes and say all the wrong things. I’m so afraid that I’ll let you down, Father.’

‘You could never do that, Amalia.’

‘I’m trembling with nerves already.’

‘That will soon pass. We’ve been invited to see the progress made on the palace, not summoned there so that the duchess can criticise your apparel and click her tongue at your manners. Besides,’ he went on, ‘you’ve met her husband a number of times and the duke has always been very gracious to you.’

‘His wife may be much more censorious,’ she said with concern. ‘Daniel has told me a little about her. She’s a determined lady with a mind of her own and she doesn’t suffer fools gladly.’

He chuckled. ‘Since when have you been a fool?’

‘The duchess is so close to Her Majesty, the Queen, that they are virtually sisters. Do you see what I mean, Father? It’s so daunting. When we get to England, our hostess will be a person who rubs shoulders with royalty.’

‘There’s nothing remarkable in that,’ he riposted with a twinkle in his eye. ‘I, too, have consorted with royalty. I lost count of the number of times I saw the king when I was at Versailles. He often spared me a few words – until he learnt that I was not simply there to weave a tapestry for him. We have that consolation,’ he added with a laugh. ‘Whatever happens, the duchess will not have us thrown into prison.’ He put a comforting arm around her. ‘Put away all fear, Amalia. You have nothing to be worried about. The duchess will find you as charming and lovely as everyone else does.’

She was uncertain. ‘Do you think so, Father?’

He gave a shrug. ‘If it causes you such distress, I can see that I’ll have to go to England myself.’

‘No, no,’ she cried, ‘I won’t be left behind. Give me the letter so that I can read it again.’ She snatched it from him. ‘It’s marvellous news. I can’t wait to tell Daniel about it when I next write to him.’

Though he was now attached to Marlborough’s staff, Daniel always made time whenever he could to visit his own regiment and see his friends. Chief among them was Sergeant Henry Welbeck, a man who’d known him since the time when Daniel himself had served in the ranks. Lacking the money to purchase a commission, Daniel owed his promotion to repeated acts of heroism in the face of enemy fire. His advancement had thus been strictly on merit. Nothing would induce Welbeck to join the officer class. In his view, they were an odious breed. He retained a barely concealed contempt for those above him, having seen too many of his men killed because of foolish decisions taken in battle by people with no business to be in command. Daniel was the only officer who’d earned his respect and affection.

They met outside Welbeck’s tent.

‘What news, Dan?’ asked Welbeck, puffing on his pipe.

‘We are to lay siege to Lille.’

‘Even I’d worked that out.’

‘What you don’t yet know,’ said Daniel, ‘is that Prince Eugene will be in command with fifty battalions and ninety squadrons, mostly of Dutch and imperial troops.’

‘Go on.’

‘They are to be supported by a brigade of five British regiments, one of which will be our own dear 24th.’

Welbeck’s nose wrinkled with displeasure. ‘So we’ll be taking orders from a foreigner, will we?’

‘Prince Eugene is a gallant soldier.’

‘He’s far too gallant, in my opinion,’ said Welbeck. ‘He likes to lead his men into battle and expose himself to unnecessary danger. I’d rather serve under a man like the duke who’s sensible enough to conduct affairs from a position of relative safety.’

‘His Grace doesn’t always hold back,’ Daniel reminded him. ‘I was there when he led a charge at Ramillies.’

‘It’s just as well you were there, Dan. My spies tell me that our beloved captain-general was thrown from his horse. If you hadn’t been on hand to rescue him, the Grand Alliance would now be under the control of some stupid, half-blind, weak-willed Dutch general with no idea of military strategy.’ He bared his teeth in a hostile grin. ‘The only thing the Dutch ever do with enthusiasm is to turn tail.’

Smiling tolerantly, Daniel refused to rise to the bait. Welbeck was a stocky man of middle height, with an ugly face given a sinister aspect by the long scar down one cheek. The sergeant’s body, as his friend knew, bore even more livid reminders of a soldier’s life. In the course of various skirmishes and battles, Welbeck had been shot, stabbed by a bayonet and slashed in several places by a sabre. He bore his injuries without complaint.

‘So,’ he said, eyeing Daniel up and down, ‘while I’m undertaking the siege of Lille with the rest of the regiment, what will Captain Rawson be doing?’

‘I’m awaiting orders from on high.’

Welbeck looked up at the sky. ‘I didn’t realise that you were in touch with the Almighty. You’ll be telling me next that you hear voices – just like Joan of Arc.’

‘The only difference is that she heard them in French,’ said Daniel with a laugh. ‘No, Henry, my orders come from closer to the earth. His Grace always dreams up something interesting for me.’

‘When is he going to dream up a peace treaty?’

‘When – and only when – we’ve finally won this war.’

Before he could reply, Welbeck noticed someone coming towards them. Daniel recognised the newcomer at once. It was Rachel Rees, riding a horse and pulling her donkey behind her on a lead rein. She wore the same rough clothing as before but now sported a wide-brimmed hat with feathers stuck in it. When she waved familiarly at them, Welbeck was unwelcoming.

‘What, in the sacred name of Satan, have we got here?’

‘She’s a lady I met on my travels,’ said Daniel.

‘Then you must travel to some strange places, Dan. Look at her, will you? She didn’t get that fat on army food, and what is the woman wearing? I’ve seen better dressed beggars.’

‘Her name is Rachel Rees and she’s Welsh.’

‘That’s even worse!’ snorted Welbeck, pulling his pipe from his mouth and tapping it on the sole of his boot to dislodge the tobacco. ‘I know we’re desperate for recruits, but we’re surely not taking on roly-poly ragamuffins like her.’

‘Keep your voice down, Henry, and show her some respect.’

‘Respect? How can anyone respect a vagabond?’

‘Rachel is no vagabond, as you’ll find out.’

When she finally reached them, she hopped off the horse and exchanged greetings with Daniel before smiling at Welbeck.

‘This is Sergeant Welbeck,’ introduced Daniel, ‘and I’d better warn you that he’s a confirmed misogynist.’

She was baffled. ‘What on earth is that?’

‘I don’t like women,’ said Welbeck, bluntly.

‘That’s only because you haven’t met the right one yet,’ said Rachel, cheerfully. ‘Will Baggott was the same. He was my first husband and a more defiant woman-hater you couldn’t wish to meet. Then I came into his life and his eyes were suddenly opened.’ She gave a throaty cackle. ‘He made up for lost time. Will was a corporal in the Grenadiers until he was killed in action.’

‘Did you manage to sell the horses?’ asked Daniel.

‘Yes, Captain Rawson, and I got a fair price for both of them.’

Welbeck frowned. ‘What’s this about selling horses?’

‘I should explain,’ said Daniel. ‘Rachel and I met when she was having an argument with a Hessian cavalry officer who’d promised to buy a horse from her. He decided to steal it instead.’

‘He tried to steal more than the horse,’ she recalled with a grimace. ‘If the captain hadn’t arrived in time, I’d have been violated. Instead of that, I finished up owning the fellow’s horse as well.’

‘It was his own fault, Rachel. The long walk back to his regiment would have taught him to behave more honourably in future.’

‘He’s probably still nursing his wounds.’ She turned to Welbeck. ‘The captain beat him soundly, then knocked him senseless. He had to stop me from kicking the scoundrel’s head in. Anyway,’ she continued, putting a hand under the folds of her dress, ‘I came to show you my appreciation by bringing you a gift.’ She pulled out a dagger. ‘This is for you, Captain Rawson.’

The two men were astounded. The dagger had an ornate handle and there were tiny jewels set into the leather sheath. When she drew out the long, razor-sharp blade, it glinted in the sun. Welbeck struck an accusatory note.

‘Where did you steal that from?’ he demanded.

‘I took it from the French major who tried to stab me with it,’ she told him. ‘It was after the battle of Ramillies. He was lying on the ground near to death and decided to take me with him. I’d already lost my second husband that day so I was throbbing with anger. I took the dagger from his hand and used it to finish him off.’ She smiled grimly. ‘That Frenchie had no use for the weapon so I kept it.’

‘That’s not stealing,’ said Daniel. ‘It’s serendipity.’

‘It sounds like thieving to me,’ asserted Welbeck.

‘And how many things have you picked up on a battlefield?’ she challenged. ‘If you’d seen a dagger like this, would you have left it lying there for someone else to claim? No, Sergeant Welbeck, you wouldn’t. In the wake of a battle, all of you grab whatever souvenirs you can. That’s what Ned Granger did – he was my second husband – and he built up quite a collection. Ned was a sergeant as well. He served in the 16th Regiment of Foot.’ Sheathing the dagger, she offered it to Daniel. ‘Please accept this small token of my undying gratitude.’

‘Thank you, Rachel,’ said Daniel, taking the weapon and examining it. ‘It’s a fine piece of work and I’ll treasure it.’

‘I’d rather you used it to kill more Frenchies. And don’t forget what I said,’ she added, wagging a finger. ‘Whenever you need any help, call on Rachel Rees.’ Her eyes flitted to Welbeck. ‘The same goes for you, Sergeant. It’s clear to me that you’re more in need of help than the captain.’

Welbeck bristled. ‘Why should I need help?’

‘Someone has to change your warped view of women.’

‘I don’t like them, that’s all.’

‘Does that mean you despised your mother?’

‘Well, no – of course not. She was different.’

‘What about your grandmother?’

‘What about her?’ asked Welbeck.

‘I can’t believe you hated her as well.’

‘She was family – it doesn’t count.’

‘Ah, I see,’ said Rachel, ‘you like all the women who belonged to your family and loathe the rest of us. What about religion? If you’re a Christian, it must mean you love the Virgin Mary, not to mention all those other good ladies in the Bible. The tally is mounting all the time, isn’t it? You don’t hate all women. There are quite a few you like.’

‘It’s a fair point, Henry,’ said Daniel, enjoying the exchange.

‘Do you know what I think?’ said Rachel.

‘No,’ retorted Welbeck, ‘and I don’t care.’

‘You’re hiding behind this so-called hatred. The only reason you pretend to detest women is that you’re afraid of us.’

Welbeck exploded. ‘I detest them because they always get in the way – just as you’re doing right now. Women are a distraction in the army. They turn men’s heads and make them lose concentration. They lie, they cosset, they badger, they deceive, they demand and they talk a man’s ear off. Afraid of women?’ said Welbeck with disgust. ‘The only thing that scares me is that their tongues never stop wagging.’

‘Oh, is that all?’ asked Rachel, shaking with mirth.

‘Keep away from me,’ he warned.

‘You talk just like Will Baggott, though his language was much coarser. It took me a long time to win him over but I managed it in the end.’ She moved in closer to scrutinise his face. ‘You even look a bit like old Will with that same nasty, unfriendly expression. You only ever see it on the faces of poor, cold-hearted men who’ve never been properly warmed through by a woman.’

Welbeck was pulsing with fury. ‘Can you see now why I hate them so much, Dan?’ he said, rancorously. ‘They’re harridans – all of them. I’ll speak to you later when we’re able to get a word in.’ Turning on his heel, he plunged into his tent. ‘Goodbye.’

‘I think you frightened him off,’ said Daniel. ‘There are not many people who can make Henry take a backward step.’

‘I didn’t mean to do that, Captain Rawson. It’s just that he did remind me so of my first husband. The only difference is that the sergeant is much better looking than Will Baggott.’

Daniel gasped. ‘Henry is better looking?’

‘Oh, yes,’ she said. ‘Put a smile on him and he’d look almost handsome in an ugly sort of way. My instincts about men are never wrong. Yes,’ she went on, gazing pensively at the tent, ‘I might have offered my help to you, but Sergeant Welbeck is the one who really deserves it. He needs the magic of a woman’s touch in his life.’

CHAPTER THREE

Marshal James FitzJames, Duke of Berwick, arrived in the camp with his entourage and went straight to the quarters of its commander. He was dismayed to find the Duke of Vendôme reclining indolently on a couch with a glass of wine in his hand while attended by a handsome officer whose uniform was unbuttoned. Vendôme, who was as usual scruffily dressed, did not even rise to his feet to greet his visitor. His one concession to the newcomer was to dismiss his companion with a lordly wave of his hand. Buttoning up his uniform and putting down his glass, the man mumbled his apologies to Berwick and left swiftly. Berwick looked after him.

‘He’s rather young to be a captain,’ he observed.

‘Raoul Valeran is worthy of his promotion,’ said Vendôme, sitting up. ‘He’s proved himself on the battlefield and is a man on whom I can rely completely. But do sit down, Your Grace,’ he went on, indicating a chair. ‘May I offer you wine?’

Berwick was brusque. ‘No, thank you.’

‘Would you care for some other refreshment?’

‘I merely came to discuss military matters,’ said the other, lowering himself into a chair. ‘I expected to find you finalising your strategy, not entertaining a guest.’

‘Captain Valeran is a valued friend.’

Berwick understood what that meant. Now in his fifties, Vendôme was notorious for his sexual appetite and would often travel with his latest mistress in tow. When no woman was available, he would take equal pleasure in the company of a man. Evidently, Captain Valeran was his current favourite. Berwick wondered how the smart young officer could bear to get so close to a man whose filthy clothing, spattered with food and wine stains, gave off a noisome smell. Vendôme might be a veteran soldier but his personal habits were offensive to someone as neat and fastidious as Berwick.

‘Well,’ said Vendôme, lazily, ‘I can see that you’re upset about something. Speak your mind, I pray.’