7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

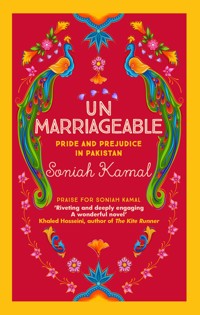

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

A FRESH AND DELIGHTFUL RETELLING OF THE JANE AUSTEN CLASSIC When Alys's family is invited to the wedding of the century in their town, her mother, the indomitable Mrs Binat, excitedly coaches her five unmarried daughters on the art of husband hunting. Alys's eldest sister Jena quickly catches the eye of a wealthy entrepreneur. But his friend Valentine Darsee doesn't conceal his unfavourable opinion of the Binat family. As the days of lavish festivities continue, the Binats wait breathlessly to see if Jena will land a proposal - and Alys realises that Darsee's brusqueness hides a very different man to the one she judged at first sight.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 520

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Praise for Unmarriageable

‘Kamal masterfully transports Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice from Regency England to modern-day Pakistan in this excellent retelling … [A] funny, sometimes romantic, often thought-provoking glimpse into Pakistani culture, one which adroitly illustrates the double standards women face when navigating sex, love and marriage. This is a must-read for devout Austenites’

Publishers Weekly *starred review*

‘Irreverent, witty, and imaginative. Readers will be surprised by the similarities between the customs and manners of 19th century England and those of modern-day Pakistan. Austen herself would have enjoyed Kamal’s deft retelling of her novel, while sipping a cup of chai’

Thrity Umrigar, bestselling author of The Space Between Us

‘Soniah Kamal has gifted us a refreshing update of a timeless classic. Unmarriageable raises an eyebrow at a society which views marriage as the ultimate prize for women. Crackling with dialogue, family tensions, humour and rich details of life in contemporary Pakistan, Unmarriageable tells an entirely new story about love, luck and literature’

Balli Kaur Jaswal, author of Erotic Stories for Punjabi Widows

‘Unmarriageable is a joyride featuring all the beloved Austen characters with a Pakistani twist, drawing on universal themes of love, passion, and the healing nature of tea. I read it in one gulp!’

Amulya Malladi, bestselling author of A House for Happy Mothers and The Mango Season

UNMARRIAGEABLE

Pride and Prejudice in Pakistan

Soniah Kamal

For Mansoor Wasti, friend, love, partner, and Buraaq, Indus, Miraage, heart, soul, life

Upon the whole, however, I am … well satisfied enough. The work is rather too light, and bright, and sparkling; it wants shade; it wants to be stretched out here and there with a long chapter of sense, if it could be had; if not, of solemn specious nonsense, about something unconnected with the story; an essay on writing, a critique on Walter Scott, or the history of Buonaparte, or anything that would form a contrast, and bring the reader with increased delight to the playfulness and epigrammatism of the general style.

Jane Austen on Pride and Prejudice in a letter (1813) to her sister, Cassandra

I have no knowledge of either Sanscrit or Arabic … I have never found one among them [Orientalists] who could deny that a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia. The intrinsic superiority of the Western Literature … we are free to employ our funds as we choose, that we ought to employ them in teaching what is best worth knowing, that English is better worth knowing than Sanscrit or Arabic … that it is possible to make natives of this country thoroughly good English scholars, and that to this end our efforts ought to be directed … We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern – a class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect. To that class we may leave it to refine the vernacular dialects of the country.

From Thomas Babington Macaulay’s ‘Minute on Education’, 1835

CONTENTS

PART ONE

DECEMBER 2000

CHAPTER ONE

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a girl can go from pauper to princess or princess to pauper in the mere seconds it takes for her to accept a proposal.

When Alysba Binat began working at age twenty as the English literature teacher at the British School of Dilipabad, she had thought it would be a temporary solution to the sudden turn of fortune that had seen Mr Barkat ‘Bark’ Binat and Mrs Khushboo ‘Pinkie’ Binat and their five daughters – Jenazba, Alysba, Marizba, Qittyara, and Lady – move from big-city Lahore to backwater Dilipabad. But here she was, ten years later, thirty years old, and still in the job she’d grown to love despite its challenges. Her new batch of Year 10s were starting Pride and Prejudice, and their first homework had been to rewrite the opening sentence of Jane Austen’s novel, always a fun activity and a good way for her to get to know her students better.

After Alys took attendance, she opened a fresh box of multicoloured chalks and invited the girls to share their sentences on the blackboard. The first to jump up was Rose-Nama, a crusader for duty and decorum, and one of the more trying students. Rose-Nama deliberately bypassed the coloured chalks for a plain white one, and Alys braced herself for a reimagined sentence exulting a traditional life – marriage, children, death. As soon as Rose-Nama ended with mere seconds it takes for her to accept a proposal, the class erupted into cheers, for it was true: a ring did possess magical powers to transform into pauper or princess. Rose-Nama gave a curtsy and, glancing defiantly at Alys, returned to her desk.

‘Good job,’ Alys said. ‘Who wants to go next?’

As hands shot up, she looked affectionately at the girls at their wooden desks, their winter uniforms impeccably washed and pressed by dhobis and maids, their long braids (for good girls did not get a boyish cut like Alys’s) draped over their books, and she wondered who they’d end up becoming by the end of secondary school. She recalled herself at their age – an eager-to-learn though ultimately naive Ms Know-It-All.

‘Miss Alys, me me me,’ the class clown said, pumping her hand energetically.

Alys nodded, and the girl selected a blue chalk and began to write.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a young girl in possession of a pretty face, a fair complexion, a slim figure, and good height is not going to happily settle for a very ugly husband if he doesn’t have enough money, unless she has the most incredible bad luck (which my cousin does).

The class exploded into laughter and Alys smiled too.

‘My cousin’s biggest complaint,’ the girl said, her eyes twinkling, ‘is that he’s so hairy. Miss Alys, how is it fair that girls are expected to wax everywhere but boys can be as hairy as gorillas?’

‘Double standards,’ Alys said.

‘Oof,’ Rose-Nama said. ‘Which girl wants a moustache and a hairy back? I don’t.’

A chorus of I don’ts filled the room, and Alys was glad to see all the class energised and participating.

‘I don’t either,’ Alys said complacently, ‘but the issue is that women don’t seem to have a choice that is free from judgement.’

‘Miss Alys,’ called out a popular girl. ‘Can I go next?’

It is unfortunately not a truth universally acknowledged that it is better to be alone than to have fake friendships.

As soon as she finished the sentence, the popular girl tossed the pink chalk into the box and glared at another girl across the room. Great, Alys thought, as she told her to sit down; they’d still not made up. Alys was known as the teacher you could go to with any issue and not be busted, and both girls had come to her separately, having quarrelled over whether one could have only one best friend. Ten years ago, Alys would have panicked at such disruptions. Now she barely blinked. Also, being one of five sisters had its perks, for it was good preparation for handling classes full of feisty girls.

Another student got up and wrote in red:

It is a truth universally acknowledged that every marriage, no matter how good, will have ups and downs.

‘This class is a wise one,’ Alys said to the delighted girl.

The classroom door creaked open from the December wind, a soft whistling sound that Alys loved. The sky was darkening and rain dug into the school lawn, where, weather permitting, classes were conducted under the sprawling century-old banyan tree and the girls loved to let loose and play rowdy games of rounders and cricket. Cold air wafted into the room and Alys wrapped her shawl tightly around herself. She glanced at the clock on the mildewed wall.

‘We have time for a couple more sentences,’ and she pointed to a shy girl at the back. The girl took a green chalk and, biting her lip, began to write:

It is a truth universally acknowledged that if you are the daughter of rich and generous parents, then you have the luxury to not get married just for security.

‘Wonderful observation,’ Alys said kindly, for, according to Dilipabad’s healthy rumour mill, the girl’s father’s business was currently facing setbacks. ‘But how about the daughter earn a good income of her own and secure this freedom for herself?’

‘Yes, miss,’ the girl said quietly as she scuttled back to her chair.

Rose-Nama said, ‘It’s Western conditioning to think independent women are better than homemakers.’

‘No one said anything about East, West, better, or worse,’ Alys said. ‘Being financially independent is not a Western idea. The Prophet’s wife, Hazrat Khadijah, ran her own successful business back in the day and he was, to begin with, her employee.’

Rose-Nama frowned. ‘Have you ever reimagined the first sentence?’

Alys grabbed a yellow chalk and wrote her variation, as she inevitably did every year, ending with the biggest flourish of an exclamation point yet.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single woman in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a husband!

‘How,’ Alys said, ‘does this gender-switch from the original sentence make you feel? Can it possibly be true or can you see the irony, the absurdity, more clearly now?’

The classroom door was flung open and Tahira, a student, burst in. She apologised for being late even as she held out her hand, her fingers splayed to display a magnificent four-carat marquis diamond ring.

‘It happened last night! Complete surprise!’ Tahira looked excited and nervous. ‘Ammi came into my bedroom and said, “Put away your homework-shomework, you’re getting engaged.” Miss Alys, they are our family friends and own a textile mill.’

‘Well,’ Alys said, ‘well, congratulations,’ and she rose to give her a hug, even as her heart sank. Girls from illustrious feudal families like sixteen-year-old Tahira married early, started families without delay, and had grandchildren of their own before they knew it. It was a lucky few who went to university while the rest got married, for this was the Tao of obedient girls in Dilipabad; Alys went so far as to say the Tao of good girls in Pakistan.

Yet it always upset her that young brilliant minds, instead of exploring the universe, were busy chiselling themselves to fit into the moulds of Mrs and Mum. It wasn’t that she was averse to Mrs Mum, only that none of the girls seemed to have ever considered travelling the world by themselves, let alone been encouraged to do so, or to shatter a glass ceiling, or laugh like a madwoman in public without a care for how it looked. At some point over the years, she’d made it her job to inject (or as some, like Rose-Nama’s mother, would say, ‘infect’) her students with possibility. And even if the girls in this small sleepy town refused to wake up, wasn’t it her duty to try? How grateful she’d have been for such a teacher. Instead, she and her sisters had also been raised under their mother’s motto to marry young and well, an expectation neither thirty-year-old Alys, nor her elder sister, thirty-two-year-old Jena, had fulfilled.

In the year 2000, in the lovely town of Dilipabad, in the lovelier state of Punjab, women like Alys and Jena were, as far as their countrymen and -women were concerned, certified Miss Havishams, Charles Dickens’s famous spinster who’d wasted away her life. Actually, Alys and Jena were considered even worse off, for they had not enjoyed Miss Havisham’s good luck of having at least once been engaged.

As Alys watched, the class swarmed around Tahira, wishing out loud that they too would be blessed with such a ring and begin their real lives.

‘Okay, girls,’ she finally said. ‘Settle down. You can ogle the diamond after class. Tahira, you too. I hope you did your homework? Can you share your sentence on the board?’

Tahira began writing with an orange chalk, her ring flashing like a big bright light bulb at the blackboard – exactly the sort of ring, Alys knew, her own mother coveted for her daughters.

It is a truth universally acknowledged in this world and beyond that having an ignorant mother is worse than having no mother at all.

‘There,’ Tahira said, carefully wiping chalk dust off her hands. ‘Is that okay, miss?’

Alys smiled. ‘It’s an opinion.’

‘It’s rude and disrespectful,’ Rose-Nama called out. ‘Parents can never be ignorant.’

‘What does ignorant mean in this case, do you think?’ Alys said. ‘At what age might one’s own experiences outweigh a parent’s?’

‘Never,’ Rose-Nama said frostily. ‘Miss Alys, parents will always have more experience and know what is best for us.’

‘Well,’ Alys said, ‘we’ll see in Pride and Prejudice how the main character and her mother start out with similar views, and where and why they begin to separate.’

‘Miss Alys,’ Tahira said, sliding into her seat, ‘my mother said I won’t be attending school after my marriage, so I was wondering, do I still have to do assign—’

‘Yes.’ Alys calmly cut her off, having heard this too many times. ‘I expect you to complete each and every assignment, and I also urge you to request that your parents and fiancé, and your mother-in-law, allow you to finish secondary school.’

‘I’d like to,’ Tahira said a little wistfully. ‘But my mother says there are more important things than fractions and ABCs.’

Alys would have offered to speak to the girl’s mother, but she knew from previous experiences that her recommendation carried no weight. An unmarried woman advocating pursuits outside the home might as well be a witch spreading anarchy and licentiousness.

‘Just remember,’ Alys said quietly, ‘there is more to life than getting married and having children.’

‘But, miss,’ Tahira said hesitantly, ‘what’s the purpose of life without children?’

‘The same purpose as there would be with children – to be a good human being and contribute to society. Look, plenty of women physically unable to have children still live perfectly meaningful lives, and there are as many women who remain childless by choice.’

Rose-Nama glared. ‘That’s just wrong.’

‘It’s not wrong,’ Alys said gently. ‘It’s relative. Not every woman wants to keep home and hearth, and I’m sure not every man wants to be the breadwinner.’

‘What does he want to do, then?’ Rose-Nama said. ‘Knit?’

Alys painstakingly removed a fraying silver thread from her black shawl. Finally she said, in an even tone, ‘You’ll all be pleased to see that there are plenty of marriages in Pride and Prejudice.’

‘Why do you like the book so much, then?’ Rose-Nama asked disdainfully.

‘Because,’ Alys said simply, ‘Jane Austen is ruthless when it comes to drawing-room hypocrisy. She’s blunt, impolite, funny, and absolutely honest. She’s Jane Khala, one of those honorary good aunts who tells it straight and looks out for you.’

Alys erased the blackboard and wrote, Elizabeth Bennet: First Impressions?, then turned to lead the discussion among the already buzzing girls. None of them had previously read Pride and Prejudice, but many had watched the 1995 BBC drama and were swooning over the scene in which Mr Darcy emerged from the lake on his Pemberley property in a wet white shirt. She informed them that this particular scene was not in the novel and that, in Austen’s time, men actually swam naked. The girls burst into nervous giggles.

‘Miss,’ a few of the girls, giddy, emboldened, piped up, ‘when are you getting married?’

‘Never.’ Alys had been wondering when this class would finally get around to broaching the topic.

‘But why not!’ several distressed voices cried out. ‘You’re not that old. And, if you grow your hair long again and start using bright lipstick, you will be so pret—’

‘Girls, girls’ – Alys raised her amused voice over the clamour – ‘unfortunately, I don’t think any man I’ve met is my equal, and neither, I fear, is any man likely to think I’m his. So, no marriage for me.’

‘You think marriage is not important?’ Rose-Nama said, squinting.

‘I don’t believe it’s for everyone. Marriage should be a part of life and not life.’

‘You are a forever career woman?’ Rose-Nama said.

Alys heard the mocking and the doubt in her tone: who in their right mind would choose a teaching job in Dilipabad over marriage and children?

‘Believe me, Rose-Nama,’ Alys said serenely, ‘life certainly does not end just because you choose to stay—’

‘Unmarried?’ Rose-Nama made a face as she uttered the word.

‘Single,’ Alys said. ‘There is a vast difference between remaining unmarried and choosing to stay single. Jane Austen is a leading example. She didn’t get married, but her paper children – six wonderful novels – keep her alive centuries later.’

‘You are also delivering a paper child?’ Rose-Nama asked.

‘But, Miss Alys,’ Tahira said resolutely, ‘there’s no nobler career than that of being a wife and mother.’

‘That’s fine.’ Alys shrugged. ‘As long as it’s what you really want and not what you’ve been taught to want.’

‘But marriage and children are my dream, miss!’ Tahira gazed at Jane Austen’s portrait on the book. ‘Did no one want to marry her?’

‘Actually,’ Alys said, ‘a very wealthy man proposed to her one evening and she said yes, but the next morning she said no.’

‘Jane Austen must have been from a well-to-do family herself,’ said the shy girl, sighing.

Alys gave her a bright smile for speaking up. ‘No. Jane’s mother came from nobility but her father was a clergyman. In their time, they were middle-class gentry, respectable but not rich, and women of their class could not work for a living except as governesses, so it must have taken a lot of courage for her to refuse.’

‘Jane Austen sounds very selfish,’ Rose-Nama said. ‘Imagine how happy her mother must have been, only to find that overnight the good luck had been spurned.’

‘It could also be,’ Alys said softly, ‘that her mother was happy her daughter was different. Do any of you have the courage to live life as you want?’

‘Miss Alys,’ Rose-Nama said, ‘marriage is a cornerstone of our culture.’

‘A truth universally acknowledged’ – Alys cleared her throat – ‘because without marriage our culture and religion do not permit sexual intimacy.’

All the girls tittered.

‘Miss,’ Rose-Nama said, ‘everyone knows that abstinence until marriage is the secret to societies where nothing bad happens.’

‘That’s not true.’ Alys looked pained. She thought back to the ten years her family had lived in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where she’d studied at a co-ed international school and made friends from all over the world, who’d lived all sorts of lifestyles. Though she’d been forbidden from befriending boys, many of the girls were allowed, and they were no worse off for it. Like her, they’d also been studious and just as keen to collect flavoured lip balms, scratch-and-sniff stickers, and scented rubbers, which she’d learnt, courtesy of her American classmates, were called erasers, while a rubber was a condom, which was something you put on a penis, which was pronounced ‘pee-nus’ and not ‘pen-iz’. Alys’s best friend, Tana from Denmark, stated that her mother had given her condoms when she’d turned fifteen, because, in Scandinavia, intimacy came early and did not require marriage. Alys had shared the information with Jena, who was scandalised, but Alys had quickly accepted the proverb ‘Different strokes for different folks.’

‘Premarital sex is haram, a sin,’ Rose-Nama said, ‘and you shouldn’t imply otherwise to us, Miss Alys.’ Her eyes widened. ‘Or do you believe it’s not a sin?’

Before Alys could answer, the head peon, Bashir, knocked on the door.

‘Chalein jee, Alysba bibi,’ he said, ‘phir bulawa aa gaya aap ka. Mrs Naheed requires your presence yet again.’

Alys followed Bashir down the stairs, past classrooms, past the small canteen where the teachers’ chai and snacks were prepared at a discount rate, past a stray cat huddled on the wide veranda that wrapped around the mansion-turned-school-building, past the accountant’s nook, and towards the head teacher’s office, a roomy den at the end of the front porch with bay windows overlooking the driveway for keeping an eye on all comings and goings.

The British School Group was founded twenty years ago by Begum Beena dey Bagh. The name was chosen for its suggested affiliation with Britain, although there was none. However, it was to be an English-medium establishment. Twelve years ago, Naheed, a well-heeled Dilipabadi housewife, decided to put to use a vacant property belonging to her. She sought permission from Beena dey Bagh to open a branch of the British School, and so was born the British School of Dilipabad.

Naheed had turned her institution into a finishing school of sorts for girls from Dilipabad’s privileged. Accordingly, she was willing to pay well for teachers fluent in English with decent accents, and, just as she’d all but given up on proficient English literature teachers, Alys and Jena Binat had entered her office a decade ago.

Alys entered the office now, settled in a chair facing Naheed’s desk, and waited for her to get off the phone. She gazed at the bulletin boards plastering the walls and boasting photos where Naheed beamed with Dilipabad’s VIPs. They were thumbtacked in place to allow easy removal if a VIP fell from financial grace or got involved in a particularly egregious scandal.

Naheed’s mahogany desk held folders and forms and a framed picture of her precious twin daughters, Ginwa and Rumsha – Gin and Rum – born late, courtesy of IVF treatments. Gin and Rum posed in front of the Eiffel Tower with practised pouts, blonde-streaked brown hair, and skintight jeans. Naheed’s daughters lived in Lahore with their grandparents; she’d opted to send them to the British School of Lahore rather than her own British School of Dilipabad because she wanted them to receive superior educations as well as better networking opportunities. Gin and Rum planned to be fashion designers, a newly lucrative entrepreneurial opportunity in Pakistan, and Naheed had no doubt her daughters would make a huge splash in the world of couture and an equally huge splash in the matrimonial bazaar by marrying no less than the Pakistani equivalents of Princes William and Harry.

Naheed hung up the phone and, clearly annoyed, shook her head at Alys.

‘Rose-Nama’s mother called. Again. Apparently you used the “f” word in class.’

‘I did?’

‘The “f” word, Alys. Is this the language of dignified women, let alone teachers?’

Alys crossed her arms. Naheed would not have dared speak to her like this when she’d first joined the school. Ten years ago, when Naheed had realised that Alys and Jena were Binats, her tongue had been a never-ending red carpet, for the Binats were a highly respected and moneyed clan. However, once Dilipabad’s VIPs realised that Bark Binat was now all but penniless – why he’d lost his money was no one’s worry, that he had was everyone’s favourite topic – they devalued Bark and his dependents. As soon as Mrs Naheed gleaned that Alys and Jena were working in order to pay bills and not because they were bored upper-class girls, she began to belittle them.

‘Alys, God knows,’ Naheed said, ‘I have yet again tried to calm Rose-Nama’s mother, but give me one good reason why I shouldn’t let you go.’

Alys knew that Naheed had tried to hire other well-qualified English-speaking teachers but no one was willing to relocate to Dilipabad. The sole entertainment for most Pakistanis was to eat out, and the elite English-speaking gentry in particular believed they deserved dining finer than Dilipabad offered.

‘Alys, am I or am I not,’ Naheed’s voice boomed, ‘paying you a pretty penny? It is not as if good jobs are growing on trees.’

The fact was, over the years Alys had been offered lucrative teaching positions in other cities, and then there was Dubai, where single Pakistani girls were increasingly fleeing to find their fortunes, but she was unwilling to leave her family, especially her father.

‘It was a crow,’ Alys said. ‘Rose-Nama and her mother should educate themselves on context. A giant crow flew into the classroom and startled me and—’

‘Alys,’ Naheed said, ‘I don’t care if twenty giant crows fly into the classroom and start singing “The hills are alive with the sound of music”; you absolutely may not curse in front of impressionable young ladies. Rose-Nama’s mother is right – if it’s not cursing, it’s something else. Last year you told students that dowry was a “demented” tradition. Could you not have used “controversial” or “divisive” or “contentious”? You of all people should be sensitive to diction. Then you told them that divorce was not a big deal! Another year you told them that they should be reading Urdu and regional literature instead of English. An absurd statement from an English literature teacher.’

‘Not “instead”. I said “side by side”.’

‘Yet another time you decided to inform them that if Islam allowed polygamy, then it should allow polyandry. This is a school. Not a brothel.’

Alys said, stiffly, ‘I want my girls to at least have a chance at being more than well-trained dolls. I want them to think critically.’

Naheed pointed above Alys’s head. ‘What is the school motto?’

Alys spoke it by rote. ‘“Excellence in Obedience. Obediently Excellent. Obey to Excel.”’

‘Precisely,’ Naheed said. ‘The goal of the British School Group is for our girls to pass their exams with flying colours so that they become wives and mothers worthy of our nation’s future VIPs. Please stick to the curriculum. I’m weary of apologising to parents and making excuses for you. Also, I know you value your younger sisters studying here.’

Alys gave a small smile. Qitty, in Year 12, and Lady, in Year 10, attended BSD at the discount rate offered to faculty family, which, all the teachers agreed, was not as generous as it could be.

‘I may not be able to protect you any longer,’ Naheed said. ‘Begum Beena dey Bagh’s nephew is returning from completing his MBA in America, and things seem to be about to change. For one, the young man plans to abolish the uniform. Can you imagine our students turning up in whatever they choose to wear? Anarchy!’

Alys understood Naheed’s concern. She and her husband had the monopoly over the British School of Dilipabad’s uniform business – winter, spring, autumn – and the loss would be an expensive hit to their income.

Mrs Naheed’s gaze fixed upon the driveway. Alys turned to see a Pajero with tinted windows and green government number plates driving in. The jeep stopped and the driver handed the gate guard a packet. Minutes later, Naheed tenderly opened a pearly oversize lavender envelope embossed with a golden palanquin. All smiles, she drew out equally pearly invites to Dilipabad’s most coveted event: the NadirFiede wedding, the joining of Fiede Fecker, daughter of old-money VIPs, to Nadir Sheh, son of equally important VIPs, though rumour had it that drug-smuggling was responsible for the Shehs’ fast accumulation of monies and rapid social climb and acceptance into the gentry.

‘Such a classy invitation,’ Naheed said, tucking the invites back in.

Alys disliked the word ‘classy’, a favourite of those who aimed to be arbiters of class. She knew that Naheed was hoping the Binats would not be invited, despite their pedigree, since Alys and Fiede Fecker, a graduate of the British School of Dilipabad, had been at loggerheads over incomplete assignments and projects never turned in.

‘Alys, the namigarami – the elite of Dilipabad – have spoken,’ Naheed said, fingering her invite. ‘Our duty is to send their daughters home exactly as they were delivered to us each morning: obediently obeying their parents. We are to groom these girls into the best of marriageable material. That is all.’ Naheed signalled to Bashir, who had been dawdling by the threshold, to get her a fresh cup of lemongrass tea and, in doing so, dismissed Alys.

Alys rejoined her Year 10s, bracing herself for Rose-Nama to demand her views on premarital intimacy. But Rose-Nama was busy scolding the class monitor, a timid girl Mrs Naheed had appointed because her father had given a generous donation to renovate the science laboratory. Mercifully, the bell rang as soon as she stepped in, and Alys, gathering her folders and cloth handbag, headed to the Year 11 classroom.

‘Girls,’ Alys said to Year 11, ‘open up your Romeo and Juliet. Let me remind you that Juliet is thirteen years old and Romeo around fifteen or sixteen and that they could have surely experienced a happier fate had they refrained from romance at their ages, which may well have been Shakespeare’s cautionary intent for writing this pathetically sad love story.’

CHAPTER TWO

When the final bell rang, Alys headed towards the staff room, nodding at girls giggling and gossiping around Tahira’s engagement ring. In the staff room, teachers were enjoying the celebration cake from High Chai that Tahira’s mother had sent. Alys beckoned to Jena, and both sisters headed towards the school van.

For a small fee, BSD provided conveyance to and from school for teachers and their relatives studying there. The Binats had an old Suzuki but Alys thought it wise to save on petrol, no matter how much more it embarrassed fifteen-year-old Lady to ride in the school van.

Lady and Qitty were inside the van, squabbling.

‘Qitty, move over, you fat hippo,’ Lady said, elbowing the sketchbook her elder sister was drawing in.

‘Shut up!’ Qitty said. She was the only overweight Binat sister, a blow she could never forgive fate or God. ‘There’s no such thing as a thin hippo, so fat is redundant, stupid.’

‘You’re stupid, bulldozer,’ Lady said. ‘You always hog all the space, hog. And stop showing off your stupid drawings.’

‘You wish you could draw.’ Qitty flipped to a fresh page and within moments had outlined a caricature of Lady. ‘The only talent you have is big breasts.’

‘Thanks to which, thunder thighs,’ Lady said, ‘I’m going to make a brilliant marriage and only ride in the best of cars with a full-time chauffeur. And, Qitty, you will not be allowed in any of my Mercedes or Pajeros, because I’ll be doing you a favour by making you walk.’

Qitty drew two horns atop Lady’s caricature.

‘Lady!’ Alys said, avoiding the torn vinyl as she settled into the seat beside her best friend, Sherry Looclus, who taught Urdu at BSD. ‘Apologise to Qitty. Why do you two sit together if you’re going to fight?’

The van driver was, as usual, enjoying the skirmish. The rest of the teachers ignored it.

‘I pray your dreams come true,’ Jena said to Lady, ‘but that doesn’t mean you can be mean to Qitty or to anyone. We are all God’s creatures and all beautiful.’

‘Those who can afford plastic surgery are even more beautiful,’ Lady said. ‘Qitty, you fatso, stop snivelling. You know I call you fat for your own good.’

‘I eat far less than you, Jena, Alys, and Mari all put together,’ Qitty said. Lady was willowy and seemingly able to eat whatever she wanted all day long without expanding an inch. ‘It’s not fair.’

‘It’s not fair,’ Alys agreed. ‘But, then, who said life is fair? Remember, though, that looks are immaterial.’

‘Alys, you are such an aunty,’ Lady said, taking out a lip gloss and applying it with her pinkie.

‘You can call me an aunty all you want,’ Alys said, ‘but that doesn’t change the fact that looks are not the be-all and end-all, no matter what our mother says. Qitty is a straight-A student, and I suggest, Lady, you pull up your grades and realise the importance of books over looks.’

Lady stuck her tongue out at Alys, who shook her head in exasperation. Once all the teachers had climbed in, the van drove out of the gates and past young men on motorbikes ogling the departing schoolgirls. These lower-middle-class youths didn’t have a prayer of romancing a BSD girl, Alys knew, despite the fantasies that films tried to sell them about wrong-side-of-the-tracks love stories ending in marriage, because there were few fates more petrifying to a Pakistani girl than downward mobility.

Alys watched Lady’s reflection in the window. She was running her fingers through her wavy hair in a dramatic fashion. Lady was a bit boy crazy, but Alys also knew that her sisters were well aware that they couldn’t afford a single misstep, since their aunt’s slander had already resulted in the family’s damaged reputation. She tapped her sister’s shoulder, and Lady looked away as the van turned the corner.

Dilipabad glittered after the rainfall, its potholed roads and telephone wires overhead freshly washed and its dust settled. The manufacturing town claimed its beginnings as a sixteenth-century watering hole for horses and, after a national craze to discard British names for homegrown ones, Gorana was renamed Dilipabad after the actor Dilip Kumar. In more recent times, Dilipabad had grown into a spiderweb of neighbourhoods, its outskirts boasting the prestigious residences as well as the British School, the gymkhana, and upscale restaurants, while homes and eateries got shabbier closer to the town centre. In the town centre was a white elephant of a bazaar that was famous for bargains, a main petrol pump, and a small public park with a men-only outdoor gym. The elite, however, stuck to the gymkhana, with its spacious lawns, tennis and squash courts, golf course, boating on the lake, swimming pool, and indoor co-ed gym with ladies-only hours.

Mrs Binat had insisted they apply for the Dilipabad Gymkhana membership despite the steep annual dues, and since the gymkhana functioned under an old amendment that once a member, always a member, the Binats were in for life. The amendment had been added on the demand of a nawab who, after gaining entry to the gymkhana once the British relaxed their strict rule of no-natives-allowed, had been terrified of expulsion.

Though Mr Binat was seldom in the mood to attend the bridge and bingo evenings, Mrs Binat made sure she and the girls put in an appearance every now and then. Once Alys had discovered the gymkhana library, she’d spent as much time there as she had in the school library in Jeddah, where she’d first fallen in love with books: Enid Blyton. Judy Blume. Shirley Jackson. Daphne du Maurier. Dorothy Parker. L. M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables, and S. E. Hinton’s class-based novels, which mirrored Indian films and Pakistani dramas.

In the gymkhana library, Alys would choose a book from the bevelled-glass-fronted bookcase and curl up in the chintz sofas. Over the years, the dim chinoiserie lamps had been replaced with overhead lighting, all the better to read Agatha Christie, Arthur Conan Doyle, Austen, the Brontës, Dickens, George Eliot, Mary Shelley, Thackeray, Hardy, Maugham, Elizabeth Gaskell, Tolstoy, Orwell, Bertrand Russell, Wilde, Woolf, Wodehouse, Shakespeare, more Shakespeare, even more Shakespeare.

Alys pressed her forehead against the van’s window as they left behind the imposing gymkhana and passed the exalted Burger Palace, Pizza Palace, and the Chinese restaurant, Lotus, all three eateries shut until dinnertime. Only the recently launched High Chai was open and, going by the number of cars outside, doing brisk business – in local parlance, ‘minting money’ – because Dilipabadis were entertainment-starved.

Alys gazed at the cafe’s sign: HIGH CHAI in gold cursive atop pink and yellow frosted cupcakes. It took her back to a time when their mother would dress her and Jena in frilly frocks, a time before their father and his elder brother, Uncle Goga, were estranged, a time when they’d been one big happy joint family living in the colossal ancestral house in the best part of Lahore: her paternal grandparents, her parents and sisters, Uncle Goga and Aunty Tinkle and their four children.

They’d play with their cousins for hours on end. Hide-and-seek. Baraf pani. Cops and robbers. Jump rope and hopscotch. They’d fight over turns and exchange insults before making up. However, Tinkle always took her children’s side during the quarrels.

‘Why is Aunty Tinkle so rude to us?’ Alys would ask her mother. ‘Why does she act as if they’re better than us?’

Pinkie Binat replied hesitantly, ‘Her children are not better than any of you. You have the same history.’

Pinkie Binat made sure her daughters knew where they came from. The British, during their reign over an undivided subcontinent, doled out small plots to day labourers as incentive to turn them into farmers, who, later, would be called agriculturists and feudal lords, which is what the Binat forefathers ultimately became. These men then turned their attentions to consolidating land and thereby power and influence through marriage, and even during the 1947 partition the Binats managed to retain hold over their land.

It was infighting that defeated some of the Binats. After the death of his wife, Goga’s and Bark’s ailing father had increasingly come to depend on Goga and his wife, first-cousin Tajwer ‘Tinkle’ Binat, a woman who spent too much time praying for a nice nose, thicker hair, a slender waist, and dainty feet. When Binat Sr. passed away, he left his sons ample pockets of land as well as factories, but it was clear Goga was in charge and not impressed by his much younger brother’s devotion to the Beatles, Elvis, and squash. He was even less impressed by Bark’s obsession with a girl he’d glimpsed at a beauty parlour when he went to pick up Tinkle.

‘Please, Tinkle,’ Bark had begged his cousin plus sister-in-law, ‘please find out who she is and take her my proposal. If I don’t marry her, I will die.’

Tinkle knew immediately which girl had smitten Bark. She herself had found it hard to not stare at the fawn-eyed beauty and, in a benevolent mood, she returned to the salon to make enquiries into her identity: Khushboo ‘Pinkie’ Gardenaar, seventeen years old, secondary school leaver. The girl’s mother was a housewife, overly fond of candy-coloured clothes. Her father was a bookkeeper in the railways. The girl’s elder brother was studying at King Edward Medical College. Her elder sister was a less attractive version of Bark’s crush.

The girl’s family claimed ancestry from royal Persian kitchens. Nobodies, Tinkle informed Goga; basically cooks and waiters. After the brothers fell out, Tinkle would discredit Pinkie’s family by stressing that there was zilch proof of any royal connection. At the time, however, the Binats accepted the family’s claims, and so it was with fanfare that Barkat ‘Bark’ Binat and Khushboo ‘Pinkie’ Gardenaar were wed.

On the day of the wedding, Tinkle lost control of her envy. Was it fair that this chit of a girl, this nobody, should make such a stunning bride?

‘She is no khushboo, good smell, but a badboo, bad smell,’ Tinkle railed at Goga as she mocked Khushboo’s name. ‘I’m the one who went to a Swiss finishing school. I’m the one who sits on the boards of charities. But always it’s her beauty everyone swoons over. She calls a phone “foon”, biscuit “biscoot”, year “ear”, measure “meyer”. She does not know salad fork from dinner fork. How could your brother have married that lower-middle-class twit? Doesn’t Bark care that they are not our kind of people?’

Tinkle’s jealousy grew as Bark and Pinkie delivered two peach-fresh daughters in quick succession. Tinkle’s own children barely qualified for even qabool shakal, acceptable-looking. Goga tried to ignore his wife’s complaints. He had bigger matters to trouble him, including the loss of the Binats’ factories after a wave of nationalisation. Goga was doubly displeased over Bark’s welcoming attitude towards the government takeover. Could his bleeding-heart brother not see that socialism meant less money for the Binats?

In order to diversify assets, Goga invested in a series of shops in Saudi Arabia to capitalise on the newly burgeoning mall culture. He informed Bark he was needed to supervise the investment, and Bark and Pinkie dutifully packed up and, with their daughters, Alys and Jena, headed off to Jeddah.

Even though Pinkie had been reluctant to leave her life in Lahore, once in Jeddah, frequent visits to the holy cities of Mecca and Medina were a great spiritual consolation. Alys and Jena were enrolled in an international school, where their classes looked like a mini-United Nations and the girls made friends from all over the world. Pinkie’s friends were other expatriate wives, with whom she spent afternoons shopping in the souks and malls for gold and fabrics. The Binats resided in an upscale expat residential compound, which had a swimming pool and a bowling alley, and Pinkie hired help.

Life was good; Jeddah was home. Bark grumbled occasionally about the hierarchy – Saudis first, then white people, no matter their level of education or lineage, then everyone else. Still, they might have remained in Jeddah forever were it not for a car accident in which a Saudi prince rear-ended Bark’s car. In Saudi Arabia, the law sided with Saudis no matter who was at fault, and so Bark counted his blessings for escaping with only a broken arm and, fearing that he might be sent to jail for the scratch on the prince’s forehead, packed up his wife and their now five daughters and moved back into their ancestral home in Lahore.

It took two years for Bark to unearth the rot. His elder brother had bilked him out of business and inheritance. Bark proceeded to have a heart attack, a mild one, but Tinkle made sure Goga remained unmoved by his younger brother’s plight.

Bark had nowhere to turn. His parents had passed away. Relatives commiserated but had no interest in siding with Bark or helping him money-wise. Alys, then nineteen, convinced her father to consult a lawyer. They were the talk of the town as it was, she said, and they needed to get back what was rightfully theirs. Too late, said the lawyer. They could appeal, but it would take forever and Goga had already transferred everything to himself. They would learn later that the lawyer had accepted a decent bribe from Goga to dissuade them from filing.

Tinkle wanted them gone from the Binat ancestral home, and Bark shamefacedly accepted the property in Dilipabad that Tinkle didn’t want because of its ominous location in front of a graveyard. Bark told Pinkie that she could no longer afford to be superstitious and that they had to move as soon as possible, and so Jena and Alys were disenrolled from Kinnaird College and Mari, Qitty, and Lady from the Convent of Jesus and Mary school.

The Binats arrived in Dilipabad one ordinary afternoon, the moving truck unceremoniously dumping them outside their new house with its cracked sign proclaiming: BINAT HOUSE. Binat House was an abundance of rooms spread over two storeys, which looked out into a courtyard with ample lawn on all four sides, gone to jungle. The elderly caretaker was shocked to see the family. As he unlocked the front doors and led them into dust-ridden rooms with musty furniture covered by moth-eaten sheets, he grumbled about not having been informed of their coming. Had he known, of course the rooms would have been aired. Cobwebs removed from the ceiling. Rat droppings swept off the floors and a fumigator called. Electricity and boiler connections reinstalled. A hot meal.

The Binats stared at the caretaker. Finally, Hillima, the lone servant who had chosen to accompany the fallen Binats – despite bribes by Tinkle, Hillima was loyal to Pinkie, who’d taken her in after she’d left her physically abusive husband – told the caretaker to shut up. It was his job to have made sure the house remained in working order. Had he been receiving a salary all these years to sleep?

Hillima assembled an army of cleaners. A room was readied for Mr Binat. The study emerged cosy, with a gorgeous rug of tangerine vines and blue flowers, leather sofas, and relatively mildew-free walls. Once the bewildered Mr Binat was deposited inside, with a thermos full of chai and his three younger daughters, attention turned to the rest of the house.

Mrs Binat and Alys and Jena decided to pitch in; better that than sitting around glum and gloomy. They coughed through dust and scrubbed at grime and shrieked at lizards and frogs in corners, though Alys would bravely gather them up in newspaper and deposit them outdoors. Dirt was no match for determined fists, and Alys and Jena were amazed at their own industriousness and surprised at their mother’s. They’d only ever seen her in silks and stilettos, fussing if her hair was out of place or her make-up smudged. Grim-faced, Mrs Binat snapped that before their father married her, she’d not exactly been living like a queen. Soon floors sparkled, windows gleamed, and, once the water taps began running from brown to clear, Binat House seemed not so dreadful after all.

Hillima was pleased with the servants’ quarters behind the main house – four rooms with windows and attached toilet, all hers for now, since the caretaker had been fired for incompetence.

Bedrooms were chosen. Alys took the room overlooking the graveyard, for she was not scared of ghosts-djinns-churails, plus the room had a nice little balcony. In their large bedroom on the ground floor, Mrs Binat brought up to Mr Binat – as urgently as possible, without triggering another heart attack – the matter of expenses. Pedigree garnered respect but could not pay bills. There was the small shop in Lahore that Goga had missed in his usurpations, which they still owned and received rent on, but it wasn’t enough to live on luxuriously. Gas bills. Electricity bills. Water bills. The younger girls had to go to school. Mr Binat’s heart medicines. Food. Clothes. Shoes. Toiletries. Sanitary napkins – dear God, the cost of sanitary napkins. Gymkhana dues. Hillima’s salary, despite free housing, medical, and food. They also needed to hire the most basic of staff to help Hillima: a dhobi for clean, well-starched clothes, a gardener, a cook. How dare Mr Binat suggest she and the girls cook! Were Tinkle Binat and her daughters chopping vegetables, kneading dough, and washing pans? No. Then neither would Pinkie Binat and her daughters.

It was Alys’s decision to look for a teaching job. She and Jena had been in the midst of studying English literature, and their first stop was the British School of Dilipabad. Mrs Naheed pounced on them, particulary thrilled with their accents: the soft-spoken Jena would teach English to the middle years, and the bright-eyed Alys would teach the upper years. Alys and Jena were giddy with joy. Newly fallen from Olympus, they were inexperienced and nodded naively when Naheed told them their salary, too awestruck at being paid at all to consider they were being underpaid. What had they known about money? They’d only ever spent it.

Alys and Jena had returned home with the good news of their employment only to have Mrs Binat screech, ‘Teaching will ruin your eyesight! Your hair will fall out marking papers! Who will marry you then? Huh? Who will marry you?’

She’d turned to Mr Binat to make Alys and Jena quit, but instead he patted them on their heads. This was the first time he’d truly felt that daughters were as good as sons, he attested. In fact, their pay cheques were financial pressure off him, and he’d happily turned to tending the overgrown garden.

Alys was always proud that her actions had led their father to deem daughters equal to sons, for she had not realised, till then, that he’d discriminated. However, looking back, she wished he’d at least advised them to negotiate for a higher salary. She wished that her mother had asked them even once what they wanted to be when they grew up instead of insisting the entire focus of their lives be to make good marriages.

Consequently, Alys always asked her younger sisters what they wanted to be, especially now that there seemed a cornucopia of choices for their generation. Qitty wanted to be a journalist and a cartoonist and dreamt of writing a graphic novel, though she said she wouldn’t tell anyone the subject until done. Mari had wanted to be a doctor. Unfortunately, her grades had not been good enough to get into pre-med and she’d fallen into dejection. After copious pep talks from Alys, as well as bingeing on the sports channel, Mari decided she wanted to join the fledging national women’s cricket team. But this was a desire thwarted by Mrs Binat, who declared no one wanted to marry a mannish sportswoman. Also, Mari suffered from asthma and was prone to wheezing. Mari turned to God in despair, only to conclude that all failures and obstacles served a higher purpose and that God and good were her true calling. Lady dreamt of modelling after being discovered by a designer and offered an opportunity, but their father had absolutely forbidden it: modelling was not respectable for girls from good families, especially not for a Binat.

Alys had fought for her sisters’ dreams. But wheezing notwithstanding, Mari was a mediocre cricket player, and, as for Lady, no matter how much Alys argued on her sister’s behalf, their father remained unmoved, for he hoped his estranged brother would reconcile with him and he dared not allow anything to interfere with that. Whatever the case, Alys was adamant that her sisters must end up earning well; now if only they’d listen to her and take their futures seriously.

The school van drove into a lower-middle-class ramshackle neighbourhood with narrow lanes and small homes, where some of the teachers disembarked. Unable to afford much help, they shed their teacher skins and slipped into their housewife skins once they’d entered their houses. They would begin dinner, aid their children with homework, and, when their husbands returned from work, provide them chai as they unwound. They would return to the kitchen and pack the children’s next-day school lunches, after which they would serve a hot dinner, clean up the kitchen, put the children to bed, and then finally shed their housewife skins and wriggle back into the authoritative teacher skins to mark papers well into the night.

Alys and Jena had heard the weariness in the staff room as teachers wondered how long they could keep up this superwoman act. Yet their jobs provided a necessary contribution to the family income – a fact their husbands and in-laws frequently chose to downplay, ignore, or simply not acknowledge – and afforded them a vital modicum of independence. The trick, the teachers sighed, was to marry a man who believed in sharing the housework, kids, and meal preparations without thinking he was doing a great and benevolent favour, but good luck with finding such a man, let alone in-laws who encouraged him to help.

The school van entered the Binats’ more affluent leafy district and stopped at the entrance to the graveyard. The Binat sisters had only to cross the road to enter their wrought-iron gate and walk up the front lawn lined with evergreen bushes to their front door. They’d barely stepped into the foyer when Mrs Binat flew out of the family room: ‘Guess what has happened?’

CHAPTER THREE

Mrs Binat was in the family room, praying the rosary for her daughters’ futures, when the mail was delivered and in it the opportunity. Hearing their voices in the foyer, she rushed to them, asking them to guess what had happened as she waved a pearly lavender envelope like a victory flag.

Alys immediately recognised the invite to the NadirFiede wedding. Lady whooped as Mrs Binat rattled off the names of all the old and new moneyed families who would be attending: Farishta Bank, Rani Raja Steels, the British School Group, Sundiful Fertilisers, Pappu Chemicals, Nangaparbat Textiles.

Mrs Binat was still dropping names as her daughters followed her into the family room, where they settled around the electric fireplace. Alys climbed into the window seat that overlooked the back lawn. She tossed a throw over her legs, making sure to hide her feet before her mother noticed that she wasn’t wearing any nail polish. Qitty and Lady sat on the floor, beside the wall decorated with photos of holidays the Binats had taken once upon a time: Jena and Alys at Disneyland, Mr Binat holding toddler Mari’s hand next to the Acropolis, Qitty nibbling on corn on the cob in front of the Hagia Sophia, the whole family smiling into the camera in front of Harrods, a newborn Lady in a pram.

‘Alys, Jena.’ Mr Binat rose from his armchair. ‘Your mother has been eating my brains ever since that invite arrived. I’m going to the garden to—’

‘Sit down, Barkat,’ Mrs Binat said sharply. ‘We have to discuss the budget for the wedding.’

Alys sighed as her father sat back down. She’d been looking forward to finishing her grading and then reading the risqué religious short story, ‘A Vision of Heaven’ by Sajjad Zaheer from the collection Angaaray, which Sherry had translated for her from Urdu into English.

‘Discuss it with Alys,’ Mr Binat said. ‘She knows the costs of things better than I do.’

‘I’m sure Alys and everyone else knows everything better than you do,’ Mrs Binat said. ‘But you are their father, and instead of worrying whether the succulents are thriving and the ficus is blooming, I need you to take an active interest in your daughters’ futures.’

‘Futures?’ Mr Binat beamed as Hillima brought in chai and keema samosas.

‘I want,’ Mrs Binat announced, ‘the girls to fish for husbands at the NadirFiede wedding.’

Alys gritted her teeth. She could see before her eyes a large aquarium of eligible bachelors dodging hooks cast by every single girl in the country.

‘Aha!’ Mr Binat said, taking a samosa. ‘Nadir Sheh and Fiede Fecker are getting married so that our daughters get married. So kind of them. Very noble! I suggest you also line up, Pinkie, my love, because between you and the girls, you are still the most beautiful one.’

‘I know you are mocking me, Barkat, my love, but a compliment is a compliment! However, once a woman births daughters, her own looks must take a back seat.’

Mrs Binat gazed at each of her daughters. From birth, Jena was near perfect, a cross between an ivory rose and a Chughtai painting, her features delicate yet sharp, good hair, good height, slender, and the disposition of an angel. Lady was a bustier, hippier, pug-nosed version of Jena and towered over her sisters at five feet nine inches (thankfully height had gone from impediment to asset!). Mari was a poor imitation of Lady, with plain features, a smallish chest, and without Lady’s spark. Qitty was exceptionally pretty, except her features were lost amid the double chins. And Alys. Oh, Alys. If only she wouldn’t insist on ruining her complexion by sitting in the sun. If only she wouldn’t butcher her silky curls. If only she’d wear some lipstick to outline those small but lush lips and apply a hint of bronzer to her natural cheekbones. What a waste on Alys those striking almond eyes. And such an argumentative girl that sometimes Mrs Binat would cry with frustration.

She extracted the cards from the invitation. ‘We have been invited to the mehndi and nikah ceremonies at the Dilipabad Gymkhana and to the walima ceremony in Lahore. Jena, Alys, Qitty, Lady, you’ll have to take days off from school.’

‘Don’t worry,’ Alys said to her mother. ‘Mrs Naheed has been invited too.’

Mrs Binat’s nostrils fluttered. ‘That means those scaly daughters of hers, Gin and Rum, will also be fishing. No doubt they will be wearing the latest designer outfits and carrying brand-name bags. Everyone will. Alys, what is the budget for new clothes?’

‘None,’ Alys said. ‘Anyway, tailor Shawkat overcharges us.’

‘How many times must I tell you that girls are only as good as their tailor, and Shawkat is worth every paisa he charges.’ Mrs Binat glared, Alys’s hair suddenly annoying her more than usual. ‘Honestly, if you wanted short hair, couldn’t you have got a nice bob like a good girl?’

Alys ran her a hand over her cropped curls and exposed nape. ‘I like this. It saves me hours in the morning.’

‘I like it too,’ Mr Binat said.

Alys smiled at her father. She’d grown up with her mother constantly telling her father what a jhali – a frump – she was, and over time Alys had realised that she was her father’s favourite for that very reason. He loved that she’d always squat beside him in the garden and dig in the soil without a second thought to broken nails, dirty palms, or a deep tan.

‘Barkat, you like everything this brainless girl does,’ Mrs Binat said. ‘Thankfully Alys has a nice neck.’

Mrs Binat’s ambitions for her daughters were fairly typical: groom them into marriageable material and wed them off to no less than princes and presidents. Before their fall, her husband had always assured her that, no matter what a mess Alys or any of the girls became, they would fare well because they were Binat girls. Indeed, stellar proposals for Jena and Alys had started to pour in as soon as they’d turned sixteen – scions of families with industrialist, business, and feudal backgrounds – but Mrs Binat, herself married at seventeen, hadn’t wanted to get her daughters married off so young, and also Alys refused to be a teenage bride. However, once their world turned upside down and they’d been banished to Dilipabad, the quality of proposals had shifted to Absurdities and Abroads.

Absurdities: men from humble middle-class backgrounds – restaurant managers, X-ray technicians, struggling professors and journalists, engineers and doctors posted in godforsaken locales, bumbling bureaucrats who didn’t know how to work the system. Absurdities could hardly offer a comfortable living, let alone a lavish one, and Mrs Binat had seen too many women, including her sister, melt from financial stress.