5,89 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Armida Publications

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

Cara, Lillian and Emilia are three women of a certain age who have only one thing in common – a love of animals. Sadly, on the Mediter- ranean island they call home, they witness appalling animal cruelty and after learning of a puppy’s death in a cardboard crushing machine, the three friends decide to do something about it. They then find themselves responsible for one of the most intriguing, and in some quarters celebrated, crime sprees in modern Cypriot history.

Untethered is more than a tale about animal rescue, it’s a story of love, loss and the incredible power of female friendship.

---

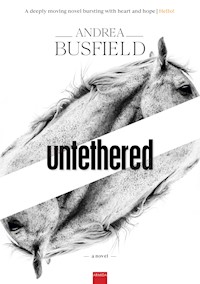

A deeply moving novel bursting with heart and hope | Hello!

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 433

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

UNTETHERED

Andrea Busfield

armida books

Copyright Page

Copyright © 2022 by Andrea Busfield

All rights reserved. Published by Armida Publications Ltd.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without permission of the publisher.

For information regarding permission, write to

Armida Publications Ltd, P.O.Box 27717, 2432 Engomi, Nicosia, Cyprus

or email: [email protected]

Armida Publications is a member of the Independent Publishers Guild (UK),

and a member of the Independent Book Publishers Association (USA)

www.armidabooks.com | Great Literature. One Book At A Time.

Summary:

Cara, Lillian and Emilia are three women of a certain age who have one thing in common – a love of animals. Sadly, on the Mediterranean island they call home there is appalling animal cruelty and after learning of a puppy’s death in a cardboard crushing machine, the three friends decide to do something about it – they then find themselves responsible for one of the most intriguing, and in some quarters celebrated, crime sprees in modern Cypriot history.

[ 1. Crime 2. Animals 3. Literary 4. Contemporary British Fiction 5. Animal Welfare 6. Women ]

Cover image:

Photo by Avi Theret on Unsplash

Back cover image:

Photo by Birgith Roosipuu on Unsplash

----

This novel is a work of fiction.

Any resemblance to real people, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

----

1st edition: March 2022

ISBN-13 (paperback): 978-9925-573-94-3

ISBN-13 (epub): 978-9925-573-95-0

ISBN-13 (kindle): 978-9925-573-96-7

Dedication

This book is dedicated to Blister, Alfie, El Disco Bastardos, Walter Pickle, Bonnie, Target, Lucky, Mina, Sundance, Mango One-Eye, Magic Tiger, Hissing China, Scraggy Ann, Fluff, Harley Baz, Jigsaw, Button Moon and the memory of my beautiful boy, Achilles.

(Shine bright, Boo).

Prologue

Somewhere in the hills, about a mile from the nearest town, the light from a single bulb seeped through the slats of two wooden shutters on a close-to-derelict drinking den that was once the area’s most popular taverna. A unique take on an old classic, kleftiko cooked in zivania, had brought the restaurant fleeting fame in the 1970s; a time when people seemed to enjoy their lamb marinated in an alcohol most commonly used to sterilise wounds. Then, as the years passed by, tastes changed, along with a catalogue of names and owners, until, four decades later, the Astraea Taverna was a crumbling ruin of its former glory and called Nicos. Somewhat surprisingly, the metal trellis at the head of the driveway remained in place, but where it had once welcomed tourists with Moorish lanterns lighting up the vibrant hues of snaking magenta and orange bougainvillea it now supported only rust. Underfoot, courtyard tiles that had fallen victim to the extremes of weather and neglect, were little more than fragments within a scrubland of weeds and spiny shrubs, and only a sprinkling of cigarette butts at the end of a gravelled pathway revealed the taverna continued to attract custom, though the damage inflicted on the once-solid walnut door gave some indication as to the type of custom the place now invited. In short, the Astraea Taverna, now known as Nicos, was a shithole.

Immediately behind the battered front door sat eight circular tables, suggesting some kind of dining area. A number of cardboard boxes, worn carpets, broken fridges and punctured bicycle tyres at the back of the room suggested a skip. Walls and ceilings that were once painted white were now nicotine yellow, and the lingering smell of cigarette smoke hung in the air like a monument to the national determination to defy modern thinking on such traditional pastimes as the inhalation of carcinogenic chemicals. In the middle of the room, between the dining area and the skip, was a counter that appeared to serve as a bar. To the right of it, a glint of light crept along the edges of the kitchen door, beyond which three voices could be heard. They were all female and they appeared to be debating the shape of the planet.

“Well, that’s just nonsense,” said the woman sat in the middle seat of a row of three chairs.

“Maybe, but go and stand anywhere, at any height, and the horizon will always be at eye level,” replied the woman to her right. She had a slight American accent though the inflection in her speech was eastern European.

“And that’s your proof?”

“Not my proof. I’m just telling you what other people believe.”

“That the earth is flat?”

“That the earth is flat.”

Lillian stared at Emilia, unsure as to whether she was having fun at her expense. The Romanian was hard to read at the best of times, but with a balaclava covering her face it was nigh on impossible to work out what was going on. She turned to Cara. “Have you heard of this?”

“I’ve heard of the Flat Earth Society,” Cara admitted. “I don’t know much about them, but they’ve been around for a while. Apparently, we’re all drifting through space on the back of a giant disc. Kind of like a Terry Pratchett novel, minus the massive elephants.”

“Oh, this is absurd,” Lillian replied testily, her exasperation compounded by the mention of elephants. She turned to Emilia. “Who the heck believes in this stuff? And how can anyone believe it’s true when photos from space clearly show the earth is round as a ball?”

“Actually, it’s not that round. It’s more like a ball squashed at both ends and as for explaining, I explain nothing,” replied Emilia, employing a studied indifference that occasionally set Lillian’s teeth on edge. Most of the time, however, Lillian liked her enormously, though she was still unused to the company of ladies bearing tattoos and piercings.

“But the photos?”

“Look, I’m with you, Lillian; the flat earth conspiracy is bullshit. But those people who like to believe in this bullshit say the photographs are lies – lies made up by the ‘Round Earth’ conspiracists.”

“Oh, give me strength.”

Emilia laughed. Though it felt unfair at times, she enjoyed toying with Lillian; she was so very British and a child of a certain age still harbouring a sentimental belief in an empire long dead. A lot of the Brits were crazy like that, or at least the ones she’d come across.

“Look, it’s like this; anyone who doesn’t believe that the earth is flat is a Round Earth conspiracist,” Emilia explained patiently. “As for the photographs taken from space, they are supposedly fakes created by NASA and other government agencies.”

“And NASA shoots anyone who tries to climb the wall,” Cara added, causing Lillian’s head to spin left with the kind of speed usually seen in Hollywood exorcisms.

“What wall? What are you on about now?”

“The 150-foot wall of ice that surrounds the earth. You probably know it better as Antarctica.” Cara raised her feet onto the front spindle of her chair, conscious of the urine creeping along the cracks in the tiled floor.

“It’s this wall that stops the oceans from emptying over the edge,” Emilia added.

“Oh, come on now, this is just silly.” Lillian shook her head. “No wall can hold back an ocean. And why would NASA, or anyone else for that matter, bother denying the earth was flat if it was true, let alone shoot people over it?”

“Because the beliefs of the Round Earthers discredit the Bible,” Cara replied.

“What’s this got to do with the Bible?”

“In the Bible it says the earth is flat, stationary and built on pillars. Or at least that’s what they say it says. I’ve never read it.”

Lillian raised her hands to her eyes, barely able to cope. The lack of faith these days astonished her. Nobody believed in God anymore and yet people were quite willing to believe they were hurtling through space on the back of a giant frisbee. “Well, I have read the Bible,” she finally said, “and I can’t say I remember anything about the earth being flat. However, I do recall the Prophet Elisha sending two she-bears out of the forest to kill 42 children for calling him ‘baldy’ and I’m not sure that’s anything we should take too literally either.”

“Nice prophet,” remarked Emilia.

“The Lord works in mysterious ways,” replied Cara.

“Like mass infanticide?”

“If you don’t mind,” Lillian muttered, and her friends, aware of her faith, shut up. “Anyway, how do you know so much about this Flat Earth thing, Cara?”

As she spoke, Emilia’s eyes widened. “No names, we said!”

Lillian winced and immediately spluttered an apology. “Do you think he heard?” she asked, the panic evident in her voice.

The three women turned their attention to the man in front of them.

Nicos, the owner of the taverna, was wiry, middle-aged and casually dressed. He was also tied to a chair. His weak chin had long ago slumped to his chest and a line of spittle had formed a bridge from his mouth to the second button of his shirt.

“I think he’s gone,” Cara said.

“Poke him with your gun,” Emilia suggested, and Lillian shuddered.

With a weary sigh and with one eye on the urine at her feet, Cara got up from her seat, took hold of Nicos’s hair, and lifted his head. The eyes were closed, the mouth was slack and his head felt as heavy as a sack of bricks. If he was listening, he was a far better actor than he was a restaurateur.

“Yep, he’s gone,” Cara informed the others, “so we better go too. To be honest, he’s starting to smell.”

Lillian raised a gloved hand to her mouth. “Come on,” she mumbled, “let’s get out of here.” Getting to her feet, she reached into her bag, pulled out a black felt tip pen and handed it to Cara.

“Where? Over there?” Cara asked and Emilia nodded.

Walking over to the white Formica table taking up space in the middle of the room, Cara drew four circles above a fat looking triangle. After filling in the shapes, she stood back.

“It should have claws,” Emilia remarked.

“Nicer without them,” Lillian replied.

“As terror signatures go, ‘nice’ isn’t normally the desired reaction,” Cara said before handing the pen to Lillian. “Have you got the chocolate?”

“I’ve got it.” Emilia passed the truffle to Cara who placed it next to her artwork. She then handed the empty box to Lillian.

“Why do I have to carry everything?”

“You have the bag,” Emilia replied.

“Not to mention the evidence,” Lillian retorted.

“Give it here then, if you’re uncomfortable. I’ll take it home and burn it.”

As Emilia reached for the bag, Lillian pulled away. “You can’t,” she said. “It’s a Louis Vuitton and my passport is in it.”

“You’re kidding me.” Cara’s eyes rolled within the sockets of her ski mask. “You’ve brought your passport to a crime scene? Why would you even do that?”

“In case of emergency,” Lillian answered feebly.

“The same reason I carry a condom,” Emilia joked.

As the two women giggled, Cara stared at them until they noticed and quietened down. Once she had their full attention, she gestured, with some exasperation, towards Nicos.

“Finished?” she asked, and Emilia and Lillian nodded. “Come on then, let’s go. It’s a hell of a walk to the car.”

“Oh God, the car...” Emilia dropped her head, reminded of the fatigue she had been fighting and trudged through the back door, held open by Cara.

Once Lillian and Emilia were outside, Cara glanced at the paw print drawn on the Formica table before turning to the unconscious figure strapped to the chair.

“Serves you right, you evil bastard,” she whispered.

She switched off the light, shut the door and followed her friends down the gravel pathway leading away from the taverna.

Chapter One

Eighteen months earlier…

It was at a charity quiz night at The Dreamers Inn in Dromos that Cara, Lillian and Emilia initially joined forces. As first meetings go it was a fairly innocuous affair with most of the drama coming from Table Eight.

“It’s Heracles.”

“No, it’s Hercules.”

“They’re the same man.”

“I can only go with what’s on the card and the card says Hercules.”

“But that’s the Roman name, not the Greek. You asked for the name of the Greek hero.”

“Card.”

Cara, Lillian and Emilia stayed out of the controversy, partly because they were strangers to the quiz scene, but mostly because they had gone with Hercules. As they were in the infancy of their friendship, they were also a little shy around each other.

It was only a week ago, on a bright, January morning, that Cara had met Lillian. Ambling towards the nearest kiosk, through a maze of white holiday villas and expat bungalows, she had seen a blue Toyota Rav4 emerge from a housing complex and proceed, at some speed, towards a well-dressed woman carrying two bags of cat food. Though the driver swerved at the last minute, the woman lost her balance and fell backwards into a wall. Naturally, Cara rushed to assist, and this is how she met Lillian; as a witness to an attempted hit-and-run.

“It’s not the first time,” Lillian revealed, her fine-featured face pale from shock and excess powder. She brushed herself down and picked up her bags.

Intrigued as to what this woman, with her neat floral dress, flat shoes and woollen cardigan, could have done to incur the wrath of someone with such alarming regularity, Cara asked.

“I feed the cats,” Lillian explained. “Not everyone approves. Some think they’re vermin.”

“And their answer is to run you over?”

Lillian smiled, wincing slightly because she had bruised her cheek in the fall. “I’m not sure anyone would actually do it, though this guy comes close at times. I think he just wants to scare me into stopping, or stop me from doing it near his house. I don’t know. Anyway, he won’t win. I’ve had alarms fitted at mine and I usually wear a GoPro strapped to my head. Thing is, I’ve just had my hair done and, well, you know how it is.”

Cara was shocked, partly because it was the first that she had heard of such dangers in the four years she had lived in Cyprus, but also because Lillian didn’t look the type to be into action cameras. She wrote down her phone number, in case Lillian wished to take things further – “and may I suggest that you do” – and bid the older woman a safer day than she’d so far had.

On arrival at the local kiosk, a little later than anticipated, it might have been fate or really bright graphics, but Cara’s eye was immediately drawn to a poster taped to the door advertising The Dreamers’ Inn quiz night ‘in aid of Tala’s Monastery Cats and the Stray Haven dog shelter’. Despite having no one to go with, having done her best to avoid making friends since moving to Cyprus, Cara was taken by a strange compulsion to attend. For some time, she had wanted to give something back to the rescue community, and though it had taken a while, she was finally growing bored of her own company.

Cara initially moved to Cyprus on a whim, nursing the kind of disappointment that comes from loving the wrong man. She arrived shortly before the economy tanked and in time to witness the Cypriot government deal with the crisis by raiding people’s savings to rescue the teetering banking sector.

“Can they do that?” her mother asked over Skype.

“I assume so as they’ve just done it,” Cara replied, and her mum muttered darkly about Greeks bearing gifts, which made no sense at all under the circumstances.

As it transpired, the raid on the rich worked pretty well for the national economy, which must have been comforting to anyone holding bank shares rather than the euros they had worked hard for, saved for and, in some cases, laundered. More out of habit than design, Cara had kept her money in the UK banking system.

After viewing a dozen or more properties ranging from one-bedroom flats to five-bedroom villas, Cara bought a traditional one-storey stone cottage, with title deeds, on the outskirts of Dromos, a large village in the western region of Paphos. It was a sweet and basic hideaway with two bedrooms, a small garden and a courtyard. The neighbours were a mix of English and German, and far enough away so as not to be seen, but close enough to help should she need to scream. At that point in her life, the isolation appealed to Cara. After a lifetime of cities, she was done with living on top of people. Or even near them. In recent years, life had become claustrophobic and she yearned for space. It might have been her age or a deeper malaise, but she had grown sick of the world with its rising intolerance and lack of humanity. But she also needed time to recover, to find herself again, and the stone cottage in Dromos afforded her that time.

With enviable sea views, Cara’s home had solar-powered hot water, wooden beams and a lemon tree in the garden. The air was clean, save for the occasional sandstorm or wildfire, and the noise was minimal. On the downside, there were mosquitoes, venomous snakes and Cyprus Tarantulas. The first time Cara saw one of those, she screamed so hard the Germans came over.

For the first month in her new home, Cara did little more than settle in and wait for the phone to ring, which she then ignored. It was petty and childish, she knew that, but she was heart sore and angry, and she wanted Tom to hurt for a while. She needed him to feel the pain of their separation so he might find a way to salvage their relationship. Cara needed Tom to fight for her. Unfortunately for her, Tom must have interpreted his unanswered calls another way entirely because, eventually, he simply stopped ringing. Cara then tried to deal with this new disappointment by earning a living.

Although Cara had bought her home outright, with savings to spare thanks to the money generated by the sale of her London flat, she hadn’t counted on the cost of Cypriot electricity nor the cash-collecting vagaries of the government, so work was not only a distraction but a creeping necessity. Of course, having chosen to live in Cyprus to distance herself from people, as well as past love, she hardly relished the thought of having to deal with them to pay her bills. So, she compromised and chose her targets wisely, a wedding planner here, a tour guide there, and a beautician; exactly the kind of chat-friendly professionals that expats and tourists flock to. From experience, Cara knew these professions were a goldmine for stories, which made them ideal contacts for feature writers, such as Cara, and as wages were not what they ought to be on the island, no hard sell was needed. Cara offered a 15% commission on any stories or interviews that she managed to get published.

As Cara half-expected, this working relationship got off to a slow start, partly because non-journalists struggle to identify potential stories and partly because they actually have jobs to do. However, after a few successful hits, the arrangement started to work, meaning her contacts enjoyed some tax-free beer money and Cara could pay her bills without dipping into her savings. The money also came in handy when she unexpectedly found herself with another mouth to feed.

Within six months of arriving in Cyprus, Cara’s solitary lifestyle came to an end when she discovered a puppy dumped in one of the communal bins. Barely three months old, the dog had, literally, been thrown away like rubbish. This was Cara’s first indication that animal rights might not be high on the national agenda.

After balancing precariously on the lip of the bin, Cara managed to grab hold of the black and tan dog without joining him. The puppy was filthy, half-starved and covered in ticks. Even so, she held him gently in her arms as he started to shake, either from cold, fear or shock, or a combination of all three. Cara was no expert, but the long ears and velvet coat suggested the puppy was a hunting dog or at least a hunting dog mix, and she knew that if she had passed by an hour or so later, the bin men would have done their job. The thought of that haunted Cara for the rest of her days.

Having no idea of what she should do, Cara took the puppy to the local vet. There, they cleaned him up, told her “this is Cyprus”, and tested him for all manner of diseases she’d never heard of and, thankfully, he didn’t have. As they worked, she asked about shelters only to be told she could try ringing, but the good ones were usually full.

“What about the bad ones?” she joked.

“You’d be better off leaving him in the bin,” was the reply.

So, once he was jabbed and beautified, Cara took the puppy home and named him Cooper.

In her 43 years on the planet, Cara had never owned a dog, which meant she was totally unprepared for the impact Cooper would have on her life. Yes, there were accidents requiring bleach and restrictions regarding restaurants, but from the moment she rescued him, nothing was more important to Cara than Cooper. Unaccustomed to the concept of unconditional love, both in terms of receiving it and giving it, Cara’s world suddenly took on a strange and brighter hue. At last, she had found something to truly live for, to nurture and protect. It was liberating to love and never consider that love as some kind of betting chip that needed to be seen and raised. She loved Cooper. She loved the way he crept onto her pillow at night and slept with his nose pressed against the back of her neck. She loved the way he watched her every move and the sight of his gums flapping in the breeze as he rode shotgun in the car with his head out of the window. She even loved that she could smell his farts and find them comforting. In all the years she had lived with Tom, not once had she thought of his farts with any kind of affection, and she wondered whether this was actually a sign that should have been heeded. Still, what was done was done and though she was more alone than she had ever been, she was surprised to find she was happy; Cara genuinely enjoyed the company of her dog, which was fortunate because four months after she rescued Cooper, she took in Peaches.

Peaches was a tiny, sandy coloured Kokoni dog and Cara almost cried when she first laid eyes on her. She was emaciated and nursing a broken jaw and burns to her back, most likely from scalding water. Found by the side of the road, and as close to death as it’s possible to be without dying, a couple of passing tourists folded her in a blanket and took her to the nearest shelter they could find. The shelter’s Dutch volunteers then brought Peaches to their favoured veterinary practice, which happened to be the very place where Cooper was getting his anal glands squeezed.

“Will she live?” asked the tall, blond man who had brought her in.

“I don’t know. Maybe. Hopefully,” the vet replied.

“Doesn’t sound great.”

“Maybe, maybe not. We’ll need to keep her for a week or so. We’ll know more once she’s x-rayed. Can you find a foster to take her while she recovers?”

“Possibly,” the man replied. “I guess she’ll need special care and meds?”

“For the burns, yes. The jaw can be set, though it could take between six and eight weeks to heal and she may require a feeding tube.”

“I’ll take her.”

Having quite forgotten that Cara was standing in the corner of the room waiting for Cooper to recover from the recent exploration of his anus, both men turned to look at her with surprise.

“You want to take her?” asked the vet.

“You want to foster?” asked the shelter guy.

“Yes, I’ll take her and, yes, I’ll foster her if you want, but if you don’t mind, I’d rather keep her.”

Chapter Two

Emilia Branza was born some 37 years ago in a village close to the city of Sibiu in Transylvania. Her family wasn’t rich, but neither were they poor, and she attended a decent school where she obtained good enough grades to earn her a place at university to study law.

For a while, everything in Emilia’s world was fine. Until one day it wasn’t.

Perhaps it was the looming reality of long hours, people in suits, and praying for the weekend that caused her to think about what she really wanted from life. And, after thinking about it, she decided she was so far off the right path that she might as well kill herself. It wasn’t that Emilia didn’t have an aptitude for a legal career, it was more the wrong attitude. In short, she was easily bored.

Boredom, or the fear of it, was a state of mind Emilia couldn’t shake off. She recognised it as a potential problem and, after some research, she discovered it was a problem with a name; thaasophobia. Still, recognising it and dealing with it was not the same thing, and try as she might, it followed her everywhere, infecting everything she did and everyone she met until eventually people did their best to avoid her. In many cases, it was wrongly assumed that Emilia was ungrateful for the gifts that life had given her, or that she was simply rude, given her tendency to look through and past people during conversations. However, Emilia wasn’t unappreciative of anything she had, not in any way, but there was a constant and relentless urge to keep on looking for what was coming next, whether it be a job, a boyfriend or a new kind of experience, because whatever state she was currently in, she worried it might be ‘it’. This would be her life until the day that she died.

“Childish, teenage angst,” was her stepmother’s diagnosis, but her stepmother was a fool. Why else would she marry a man still in love with his dead wife?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, and part-way through a three-year internship at a Bucharest legal firm specialising in maritime law, Emilia decided it was time to leave Romania. She felt the need to travel and, for the next 15 years, she never stopped. After taking a bus to Hungary she hitchhiked through Austria, skied over the Alps to Italy, got on a boat to Greece and then took a flight to Cyprus. Along the way she held down a number of jobs, some of which she kept for a few years, some only days. In Salzburg, she acted as PA to a well-known fashion designer; in Milan, she worked as a croupier; in Athens, she became an extra in a film about refugees; and in Cortina d’Ampezzo, an ancient mountain town in the Dolomites, she took a job as a chalet maid. Emilia also took a number of lovers along the way, without ever losing her heart. This was another of her peculiarities; she didn’t fully appreciate love or the dramas that went with it. All over the world, men and women were pining for people who didn’t like them enough to stay with them, or they were compromising lifestyles and life choices for a happiness that remained largely elusive. If this was love, it was lost on Emilia. At least until it found her.

It was while Emilia was living in Dromos and holding down a job as a surly waitress in one of the village’s less popular restaurants that she discovered true love, and it was tethered to a stake driven into the ground in an area of scrubland running alongside the coastal road. A bay-coloured horse with a black mane framing his handsome face, he had a white mark in the shape of India on his forehead. He also swallowed air, a habit that Emilia assumed was due to boredom. However, it was the eyes that struck Emilia most; beautiful pools of chocolate brown that pulled her into a soul she somehow knew. Emilia was no Buddhist, but she felt an unmistakable connection that felt like a past life so, when she eventually tracked down the owner, she bought the horse for far more than he was probably worth. She then named him Adonis.

Adonis was a four-year-old thoroughbred, according to the papers that came with him. Originally destined for the racetrack, he had failed to make the grade, but as he came from good stock he was handed to a government official who then gifted him to his son. Unfortunately, when Adonis failed to make the grade as a horse suitable for an overweight 14-year-old boy, a chain was slung about his neck and he was left to exist, and do little more than that, on a diet of stale bread, an occasional armful of straw and a bucket of water. Emilia’s heart bled for the animal. While her knowledge of horses wasn’t extensive, she had ridden as a child and she knew that horses needed company, preferably of their own kind, and they also needed a proper diet of hay, clover and grains. Dry pita simply wasn’t sufficient.

Emilia couldn’t explain it, but she felt compelled to save him. Of course, having never counted on becoming a horse owner, she had nowhere to put him and no food to feed him so, after fashioning a makeshift halter out of rope she bought from a hardware shop, she walked Adonis three miles to the only stables she knew of in the area. Under the burning noon day sun, it felt like a joyous and heroic march to freedom, until they arrived at their destination.

Greeted by a locked gate, Emilia called, banged, rattled and shouted for attention until it came in the form of an older woman dressed in beige breeches, a white t-shirt and a brown baseball cap. She reminded Emilia of a Frappuccino.

“Sorry, this is a private yard,” the woman replied tersely when Emilia said she was looking for somewhere to stable her horse. “You can’t bring him here.”

“But…”

“There are no buts. There are no exceptions. This is my home, not a business.”

“But please…”

“Sorry, no.”

And with that the woman promptly turned on the heel of her Italian leather boots and walked away. No doubt she would have continued walking had Emilia not screamed.

Julia Watson would later say it was one of the most agonising sounds she had ever heard come out of a human mouth, so much so it set the hairs on the back of her neck on end. When she turned around, she found the dark-haired woman at the gate now on her knees with the horse standing next to her, gently nuzzling the side of her face. Julia felt her resolve crumble. Any other horse, let alone a thoroughbred, would have been on its hind legs at such an unholy commotion. But not this guy; he simply didn’t have the energy. Slowly, she walked back to the gate.

“Are you injured?” she asked.

Emilia shook her head, not bothering to look up. “Not injured, just desperate.”

It was only meant to be a temporary stay because Julia had made it crystal clear from the start that her yard was a private yard. She also wanted €300 a month for livery, leaving Emilia with nothing from the pittance she earned at Zorbas once she’d paid her rent and the various bills that went with it. Thankfully, it only took a fortnight for Julia to thaw because some people don’t know they’re lonely until they’re forced to have company.

In spite of herself, Julia was touched by the care and devotion Emilia lavished on her horse. When Emilia wasn’t working at the restaurant, she would be at the yard; grooming, washing and generally pampering Adonis. After Julia lent her a head collar and lead rope, she would take Adonis for walks down to the Sea Caves and, after a while, she permitted them to use the arena to free school. When Julia watched them play, because this was no kind of free schooling she knew of, she was reminded of a child with a puppy. Not that it mattered. It was clear the two of them had found a rare happiness in each other’s company. Unfortunately for Emilia, Adonis was not only handsome, but also a windsucker, a vice rarely welcomed in most stables. Julia understood it was a habit borne of stress, and it was as addictive as smoking when learned. She also knew that Adonis would be prone to colic as a result, and Emilia would need someone around who knew what to do when it struck.

Almost from the outset, Julia saw that Emilia and Adonis had found each other at the right time, in much the same way they had found her. And though she couldn’t say why, she let them stay, telling Emilia that if she helped around the yard, her horse could remain at the yard, rent free. When Julia made the offer, Emilia assumed the older woman was a lesbian. Not that Emilia had anything against lesbians; she simply couldn’t see why anyone would be so generous for relatively little in return. The woman only had four horses so there wouldn’t be that much work to do. A year or so later, when their friendship had reached the point where delicate issues could be discussed with no offence taken, Julia laughed like a drain.

“Christ, if I was a lesbian, I’d hardly choose a pierced little punk like you,” she told her.

“Why is it Americans only ever say ‘punk’?”

Julia was in her mid-50s and came from Tallahassee, Florida. She wasn’t the usual type of foreigner the island attracted; expats were mainly made up of retired Britishers, high-rolling Russians and economically-challenged Romanians, although the Chinese were starting to make an impact on the housing market in return for a backdoor entrance to Europe. But the Americans, not so much. In fact, Julia was the first American Emilia had met in Cyprus.

Julia moved to the island 20 years ago, after enjoying a successful jumping career on the international stage where she fell in love with a Cypriot guy, an equestrian who also achieved better-than-average success abroad. Even so, it wasn’t enough to earn them serious money. Though the two of them possessed talent and a passion for the sport, they recognised their limitations and so, after building their reputations, they retired to his homeland and opened a livery yard for a select number of clients looking to compete internationally. They also made a handsome living from tutorials, private lessons and schooling. It was a fantastic partnership and a true meeting of minds and hearts, until, ten years into their marriage, Julia’s husband was killed by a drunk driver on the highway from Ayia Napa. Julia was inconsolable.

As the couple never had children, because they believed they had plenty of time, Julia felt her husband’s loss all the more keenly when she realised there was nothing left of him to hold. Her family begged her to return to the States, but she refused to step away from the ground in which he was buried. Indeed, it took her a long time to recover from his death and though she retained her passion for horses, she no longer had the stomach for people. So, she closed the business. She hardly needed the money. And she continued to walk through life, one day at a time, getting by with the help of her horses.

From the moment she found Adonis, Emilia could think of little else, but she still needed to work so she kept her job at Zorbas, which is where she came into contact with Lillian.

Emilia knew of Lillian long before they met because she used the restaurant’s leftovers to feed the cats in the area. Though she usually came in the mornings, one Monday Lillian was running late and arrived midway through Emilia’s afternoon shift. With a polite knock at the back door, Lillian popped her head into the kitchen where Emilia was piling plates by the sink. When she explained who she was, Emilia was surprised; Lillian was different to how she had imagined; more groomed and curiously uptight, even for the English. When the kitchen staff talked about the ‘crazy cat lady’, Emilia had pictured someone older and cuddlier. But Lillian was a well-presented woman in her fifties with razorblade cheekbones and a fine head of auburn hair. She was also polite enough to answer Emilia’s questions despite being in a hurry.

Lillian told Emilia she used the scraps from the restaurant to feed the colony of cats that congregated at the back of the village church.

“I thought I’d seen some there,” Emilia said as she bagged up the leftovers.

“I’d be surprised if you hadn’t. The cats have been there for about five years. Before that, we fed them in the car park a little further down the road, but people kept poisoning them.”

“You’re kidding?”

“Unfortunately, not.”

As the two women continued to talk, Lillian let slip that she was looking for volunteers to cover a couple of feeding stations dotted around the village. The woman who used to help had recently returned to the UK. Well, the stars might have been in alignment or it could have been the talk about poison, Emilia couldn’t be sure, but she suddenly had an urge to protect Lillian’s homeless cats.

“How much do you pay?” she asked.

Lillian winced. “Well, nothing. We have no money to pay anyone, it’s just a few of us volunteers. We buy all the food and look for scraps, we just need help to…”

“Relax, I’m joking,” Emilia eventually told her.

“Oh, I see.”

“Sorry.”

“No, it’s fine.”

“But you pay the social, yeah?”

Confusion again clouded Lillian’s eyes until it dawned on her that the younger woman was having another joke at her expense. Though she tried to smile, she actually found such humour exhausting, and she wasn’t sure she could cope with it on a daily basis. In fact, if they hadn’t already agreed to meet at the church the following day, she might have drifted quietly away, being careful to only return to Zorba’s in the mornings.

As Lillian left the restaurant with her plastic bags loaded with the cold remnants of half-finished dishes and half-chewed kebabs, Emilia half-regretted her teasing. She guessed Lillian to be the same age as Julia, or thereabouts, but there was a beaten look underneath that well-preserved exterior. A few days later, when she started feeding Lillian’s cats, she understood why – people were shits and they were especially shit to cats.

“The cats here are dying in every way possible,” Lillian explained. “Burned alive, beaten, chopped up, kicked to death, run over… I’ve seen it all. For more than ten years I’ve fed the cats here and, in all honesty, they have been the hardest ten years of my life.”

“So, why do you do it?”

“Because if I don’t, who will?”

“Ah, Lillian. She’s a funny one, but her heart is in the right place,” Julia said when Emilia revealed her latest commitment to the island’s unwanted animal population. “I don’t know her well, but I’ve donated to her cats and met her on a few fundraisers.”

“She’s typical British,” Emilia replied.

“Well, yes and no. She’s a bit stuffy, which fits the stereotype, but she tends to keep away from all that expat drinking and meddling.”

“I think I make her uncomfortable.”

“You surprise me.”

Julia nodded to the wheelbarrow in front of them. “Right madam, go and get those stables finished and I’ll bring you a coffee.”

“A biscuit would be nice.”

“I’m sure it would.”

Julia smiled, Emilia scowled, but they both knew there would be biscuits coming with the coffee.

Looking back on that day, as Julia often did in the years to come, she would occasionally be surprised by the small details that stuck. She recalled watching Emilia push her wheelbarrow up the aisle of the stables and noticing the sun’s rays bounce off her jet black hair, like light on polished stone. She remembered switching on the sprinklers to water the arena and finding a half-eaten lizard by a cavaletti jump. There were two pigeons overhead, balancing on an electrical wire, and she wondered whether they might be to blame. She recalled sighing as she entered her home because she’d left on the aircon, and though it was always nice to step into a cool room, it was wasteful and bad for the planet. She debated whether to make real coffee or instant and went with the latter after glancing at the clock and realising Emilia would have to be at Zorba’s in an hour. The coffee was made and she chose a red mug for Emilia and a yellow one for herself. Only just remembering to grab a packet of Hobnobs, she tucked them under her arm and walked back to the stables, wondering what saddle pad and bandage set to put on Apache. She called Emilia’s name, but it sounded distant in her ears. Turning the corner, she glanced up the aisle of the stable block and saw a familiar boot sticking out from under one of the gates. ‘She’s with that damn horse again,’ she half-laughed to herself until she remembered Adonis was in the paddock. She called again. Nothing. She walked up the aisle, feeling the world slow down as the blood started to charge through her veins. There was something wrong. She set the mugs on the floor and ran.

When Julia reached Adonis’ stable, she found Emilia on the floor with her head jammed against the wall. Julia crouched down carefully, startled by the tears rolling down Emilia’s flushed face.

“I can’t move,” Emilia whispered.

“What do you mean you can’t move?”

“I can’t move the left side of my body. Help me, Julia. I think I’m paralysed.”

Chapter Three

Of the three, perhaps unlikely friends, it was Lillian who had lived in Cyprus the longest, coming up for eleven years.

Despite a lifetime of wishing for the sun, it actually took Lillian and her husband more than twenty years to emigrate for a number of reasons: finances, they couldn’t afford the gamble; concerns about the children’s education; and Lillian’s unwillingness to leave all she had known and loved. Her husband Derek, on the other hand, appeared to harbour no such sentimental ties to either the UK or his children, but Lillian found herself paralysed by pending grief. However, when Derek was offered a job abroad, he issued a ‘now or never’ ultimatum, pointing out that Dan and Lucy were no longer children, but young adults; little birds who had flown the nest some time ago to start their own fledgling careers in construction and nursing.

For most of his working life Derek had been in the oil industry, in one form or another, and when the opportunity arrived to earn serious money as a risk analyst, assessing wells and de-gassing stations from an airconditioned office in Qatar, it seemed too good a chance to pass up. Derek seized the day and the immense pay packet that went with it and after a little more cajoling he and Lillian got packing. Of course, coming from a generation that occasionally mistakes prejudice for a rational distrust of Muslims, they agreed that Qatar was probably not the best place for a Western woman, no matter how sunny the climate.

“What about Cyprus?” Derek suggested. “You’ve always liked the place.”

And indeed, during the few holidays they had enjoyed there, Lillian had been very taken by the island, not least because everything was so British; from driving on the left to the number of Marks & Spencer outlets. Even so, Lillian struggled with the idea that she would no longer be in the same country as her children and if it hadn’t been for Skype, she would probably have remained in rain-lashed Cheshire. But there was Skype, and there were cheap flights every day between Stansted and Paphos, and so a villa was rented, and during the weeks that Derek was away, Lillian found company among the island’s stray cats.

Because Derek had agreed a four-week-on, four-week-off contract, it meant that Lillian spent a lot of time alone, something she had initially felt trapped by. In her previous life, she had never given much thought to finding ways to pass the time because there was none; as a housewife and a mother, life had filled the hours for her, often leaving her wanting more. Even after Dan and Lucy had grown up and moved out, Lillian had kept busy, with what she couldn’t quite recall, but there was never a still moment that she could recollect, not until they moved to Cyprus where Lillian was suddenly confronted by this huge, intimidating number of hours to fill, in a place where there were no kids, no friends and, for much of the time, no Derek.

“You’ll make friends,” her husband assured her, but socialising was his field of expertise, not Lillian’s. A robust man with a personality to match, Lillian used to watch Derek work a room with something close to astonishment, and she often wondered what it was that he had seen in a wallflower like her. In fact, looking back on their life together – all 32 years of it – it struck Lillian that most, if not all of her friendships had been instigated by Derek, in one way or another, be it a work do in which she had met other wives or a BBQ he’d organised and invited the neighbours to. Indeed, the only person she had ever come into regular contact with, unprompted by Derek, was her gynaecologist.

In the first few months of her life as an expat, Lillian concentrated on setting up home. There were the usual headaches to contend with – residency forms, internet connection, insurance coverage, hiring a pool man and dealing with ants in the kitchen – and then, once the formalities were over, there was the daily shop to keep her occupied thanks to the local fruit and vegetables having a maximum shelf life of two days. As a result, Lillian visited her local supermarket almost daily and, in order to eke out the time that little bit more, she would often read the free ads glued to the window. Most of them were posters for various tribute bands, which appeared to be something of an epidemic in the area, but there were also items for sale as well as invitations to join cultural societies, language courses and charitable enterprises. There was one advert that immediately caught her eye and it read, ‘Got too much time on your hands? Then get in touch. Me and the cats of Dromos could do with your help.” And this is how Lilliam came into contact with Primrose Merryweather.

As well as possessing the prettiest name Lillian had ever heard, Primrose was a true eccentric with a heart of gold. Although her age was never discussed, Lillian was quite capable of judging a book by its cover and she placed Primrose somewhere between late 60s and early 70s. Primrose was, in fact, 82 years old.

Their first meeting took place at the steps leading to a small, white church in the village. It was a glorious June day and as Lillian followed Primrose along a gravel pathway that skirted the church, the sound of singing cicadas was gradually joined by a chorus of cats congregating in a nearby car park. There must have been more than twenty – of various colours, sizes and hairiness – and they all came bounding towards Primrose with their tails held high and their eyes expectant. Under her wide-brimmed straw hat, Primrose smiled.

“There’s always a welcome with a hungry cat,” she said. “Ringworm too, occasionally.”

Seeing Lillian’s face change, Primrose laughed. “Wash your hands before you eat, you’ll be fine.”

Of course, Lillian did far more than wash her hands, and for the first few months, she turned up at the feeding stations armed with gloves and bacterial wipes. Although Primrose thought her neurotic, she didn’t say anything because people had their ways and she needed the help. Primrose fed three colonies of strays in the village, twice a day. As she supplied the food, the only cost to Lillian was time, which happened to be the one commodity Lillian had in abundance. So, it was a win-win situation; Lillian felt busy and useful, and Primrose was able to devote more time to the cats’ medical needs as well as the trap-and-spay programme she ran with a few other British ladies.

Although it might have surprised Primrose to hear it, Lillian felt hugely inspired by the older woman’s dedication to the village’s unwanted cats. It wasn’t only the feeding and the medical care that was impressive, but the fact that Primrose had names for them all. Her devotion was touching. She worked tirelessly to keep them healthy and she cried bitterly when they turned up beyond her help or they simply disappeared. It was rare to find an old cat in any of the colonies.

“I can’t bear to think about what happens to them,” Primrose told Lillian. “I’ve heard too much and I’ve seen too much.”

After spending close to two decades feeding the island’s feral cats, there was little cruelty Primrose hadn’t witnessed and even less she didn’t know about it. Brought to Cyprus in the 4th century, the cats were introduced to the island by St Helen to rid the place of snakes and vermin. According to Byzantine legend, the cats answered the call of two bells; one that summoned them for meals at the monastery and another that sent them out to hunt for snakes in the nearby fields.

“Nowadays, the snakes are people, and the cats don’t stand a chance,” Primrose stated one morning as she placed the bodies of two poisoned kittens in the boot of her car. Two days after she buried them, Primrose also died.

Though the two incidents were unrelated, from that day on whenever Lillian came across an injured cat, and there were too many to count over the coming years, she often heard Primrose’s bleak assessment of the local population. “People are snakes.” Though Lillian agreed, she also thought they were psychopaths.

For a number of years, Lillian fed the cats she had inherited from Primrose unaided. She nursed them, wormed them, moved them from the car park to the back of the church, gave them names and even stopped wearing gloves. In short, she became a bona fide crazy cat lady.

Even when Derek said they needed to tighten their belts, Lillian made sure the cats never suffered. And, to her immense relief, he never once moaned about it. Clearly, Derek had no understanding of the depth of her devotion or how the cats had given her life purpose when she was floundering in the dark, but she didn’t need her husband to understand. Lillian was simply grateful that he didn’t interfere or try to take over. And when his rota changed to six-weeks-on, three-weeks-off, she didn’t make a fuss. What could she say? In this day and age, she knew she ought to be grateful that Derek even had a job. It was the same when he revealed there would be less money coming in due to a change in his tax-free status.

“We’re in a global recession, Lil’, and even the oil industry is feeling the burn. I wish it were different, but it isn’t.” As Derek spoke, Lillian saw how uncomfortable he was and her heart ached. Derek might have lost much of his hair and there was a lot more padding on his once-athletic build, but she loved him nonetheless. She had always loved him. But more than that, she knew they were far better off than many people. They enjoyed a more than comfortable existence. They retained and let their home in Cheshire and they also owned an apartment in Valencia, bought in 1998 to rent out as an investment. So, while the pocket money might have tightened, the recession had no great effect on their standard of living, only the time Lillian and Derek spent together. At first, that was hard, but gradually Lillian started to make friends. Her own friends.