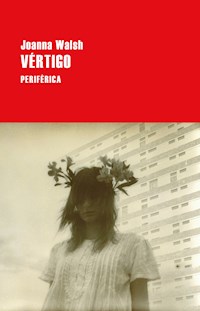

14,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: And Other Stories

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

This is a woman as a mother, daughter, wife, spectator, lover, mistress. Observer and commentator. Actor and reactor. Dressed up bright as a child or submerged in the grey elegance of Paris, she shifts readily between roles, countries, and languages. Skilled and successful, she controls how much she cares. Yet as every new woman emerges and every new story is told, each with a sharper, more deadpan, more aching simplicity, the calm surfaces of Joanna Walsh's Vertigo shatter, pulling us deep into the panic that underlies everyday life.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 121

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Praise for Vertigo

‘Joanna Walsh’s haunting and unforgettable stories enact a literal vertigo by probing the spaces between things… Her narrator approaches the suppressed state of panic coursing beneath things that are normally tamed by our blunted perceptions of ordinary life. Vertigo is an original and breathtaking book.’

Chris Kraus, author of I Love Dick

‘Think Renata Adler’s Speedboat with a faster engine… Vertigo reads with the exhilarating speed and concentrated force of a poetry collection. Each word seems carefully weighed and prodded for sound, taste, touch… The stories are delicate, but they leave a strong impression, a lasting sense of detachment colliding with feeling, a heady destabilization.’

Steph Cha, Los Angeles Times

‘Her stories reveal a psychological landscape lightly spooked by loneliness, jealousy and alienation.’

Heidi Julavits, The New York Times

‘Vertigo is a funny, absurd collection of stories.’

The Huffington Post

‘Her writing sways between the tense and the absurd, as if it’s hovering between this world and another… Vertigo may redistribute the possibilities of contemporary fiction, especially if it meets with the wider audience her work demands.’

Flavorwire, 33 Must-Read Books for Fall 2015

‘Less a collection of linked short stories—though it is that, too—than a cinematic montage, a collection of photographs, or a series of sketches, Walsh’s book would be dreamlike if it weren’t so deliciously sharp… With wry humor and profound sensitivity, Walsh takes what is mundane and transforms it into something otherworldly with sentences that can make your heart stop. A feat of language.’

Kirkus, Starred Review

‘Walsh is an inventive, honest writer. In her world, objects may be closer and far more intricate than they appear; these stories offer a compelling pitch into the inner life.’

Publishers Weekly

‘This collection makes the familiar alien, breaking down and remaking quotidian situations, and in the process turning them into gripping literature.’

Vol.1Brooklyn

‘Moments of blazing perspicacity, creativity, intelligence, and dark humour are insanely abundant in [Walsh’s] writing.’

Natalie Helberg, Numéro Cinq

‘If anyone in the course of reviewing Vertigo refers to Joanna Walsh as a “woman writer” or says the book is about women, relationships, or mothering, I will send an avenging batibat to infiltrate his dreams because that would be like saying Waiting for Godot is about a bromance… No, this book is about how embarrassing it is to be alive, how each of us is continually barred from our self… Vertigo is a writer’s coup, an overthrow of everyday language… It feels so good to see Walsh jam open the lexicon – and with such dry wit… No one else has her particular copy of the dictionary.’

Darcie Dennigan, The Rumpus

First published in the UK in 2016 by And Other Stories High Wycombe, Englandwww.andotherstories.org

First published in the US in 2015 by Dorothy, a publishing project

Copyright © Joanna Walsh 2015, 2016

Four of these stories first appeared in different form in Fractals, 3:AM Press, 2013.

The author would like to thank Lauren Elkin, Deborah Levy and Susan Tomaselli for support and advice.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transported in any form by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher.

The right of Joanna Walsh to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or places is entirely coincidental.

ISBN 9781908276803 eBook ISBN 9781908276810

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typesetting & eBook: Tetragon, London; Cover Design: Hannah Naughton. Cover Image: ‘At Sea’ by Martin Brigden, used under CC BY 2.0.

This book was also supported using public funding by Arts Council England.

Contents

Fin de CollectionVaguesVertigoYoung MothersThe Children’s WardOnlineClaustrophobiaThe Big Black SnakeAnd After…Half the World OverSummer StoryNew Year’s DayRelativityDrowningOne of these stories is for E. One is for F, one is for R, one is for L and one is for X.

Fin de Collection

A friend told me to buy a red dress in Paris because I am leaving my husband. The right teller can make any tale, the right dresser can make any dress. Listen to me carefully: I am not the right teller.

Even to be static in Saint-Germain requires money. The white stone hotels charge so much a night just to stay still. So much is displayed in the windows: so little bought and sold. The women of the quarter are all over forty and smell of new shoe-leather. I walk the streets with them. It is impossible to see what kind of woman could inhabit the dresses on display—but some do, some must.

We turn into Le Bon Marché, the women and I.

Le Bon Marché is divided into departments: fashion, food, home. It is possible to find yourself in the wrong department, but nothing bad can happen here. Le Bon Marché is always the same and always different, like those postcards where the Eiffel Tower is shown a hundred ways: in the sun, in fog, in sunsets, in snow. There are no postcards of the Eiffel Tower in the rain but it does rain in Paris, even in August, and when it does you can shelter in Le Bon Marché, running between the two ground-floor sections with one of its large orange bags suspended over your head (too short a dash to open an umbrella).

Fin de collection d’été. In Le Bon Marché it is already autumn. In 95-degree heat, we bury our faces in wool and corduroy. We long for frost, we who have waited so long for summer. In the passerelle, the walkway between the store’s two buildings, a tape-loop breeze, the sound of water, photographs of a beach.

Je peux vous aider? the salesgirl asks the fat woman with angel’s wings tattooed across her back. The woman mouths, non, and walks, with her thin companion, into the passerelle, suspended.

The first effect of abroad is strangeness. It makes me strange to myself. I experience a transfer, a transparency. I do not look like these women. I want to project these women’s looks onto mine and with them all the history that has made these women look like themselves and not like me.

There is something about my face in the mirrors that catch it. Even at a distance it will never be right again, not even to a casual glance. Beauty: it’s the upkeep that costs, that’s what Balzac said, not the initial investment.

From time to time I change my mind and sell my clothes. I sell the striped ones and buy spotted ones. Then I sell the spotted ones and buy plaid. To change clothes is to take a plunge, to holiday. The thin girl in her checked jacket looks more appropriate than I do, though her clothes are cheaper. This makes me angry. How did her look slip by me? I was always too young. And now I am too old.

I cannot forgive her. I forgive only the beauties of past eras: the pasty flappers, the pointed New Look-ers. They are no longer beautiful and cannot harm me now. Even your other women seemed tame until I saw the attention you paid them. I no longer know the value of anything. And if you do not see me, I am nothing. From the outside I look together. I forget that I am really no worse than anyone else. But how can I go on with nobody? And how, and when, and where can I be inflamed by your glance? I can’t be friends with your friends. I can’t go to dinner with you, don’t even want to.

But why does the fat woman always travel with the thin woman? Why the one less beautiful with one more beautiful? Why do there have to be two women, one always better than the other?

Je peux vous aider?

Non.

There are no red dresses in Le Bon Marché. It isn’t the dress: it’s the woman in the dress. (Chanel. Or Yves Saint Laurent.) Parisiennes wear grey, summer and winter: they provide their own colour. Elegance is refusal. (Chanel. Or YSL. Or someone.) To leave empty-handed is a triumph.

In any case, come December the first wisps of lace and chiffon will appear and with them bottomless skies reflected blue in mirror swimming pools.

To other people, perhaps, I still look fresh: to people who have not yet seen this dress, these shoes, but to myself, to you, I can never re-present the glamour of a first glance.

To appear for the first time is magnificent.

Vagues

There are many people in the oyster restaurant and they all have different relations to each other, which warrant small adjustments: they ask each other courteously whether they wouldn’t prefer to sit in places in which they are not sitting, but in which the others would prefer them to sit. Sometimes entire parties get up and the suggested adjustments are made; sometimes they only half get up then sit down again. Some of the tables in the restaurant face the beach and have high stools along one side so that diners can see the sea. Others have high stools on both sides so that some diners face the sea and others, the restaurant, but both, each other’s faces. Because of the angle of the sun and of the straw shades over the tables, the people who face the sea are also more likely to be in the shade. Not everyone can face the sea, not everyone can be in the shade.

The waitress passes. The people who face the sea cannot see her and cannot signal to her with their eyes. Facing the sea they can signal to nothing, as nothing on the beach can receive their signals, not the seagulls or the mother and toddler who are too far away, nor the occasional stork that picks through the rubbish. Yes, the beach has rubbish, though not much, and though the restaurant, by its presence, makes the rubbish unmentionable. All the beaches along this coast have some rubbish: either more or less than this beach. Here in the restaurant the diners who face the sea may notice it or ignore it, but they must accept the rubbish as part of the environment, just as they must accept the seaweed that covers the stones near the sea with a green slippery layer and which, unlike the rubbish, smells.

The smell of the seaweed must be accepted as part of the natural environment although it masks the scent of the oysters served at the bar, the smell of which is similar but different enough.

Farther along the beach, where the mother and toddler are paddling, the seaweed forms stripes of green that are pleasing, though this may be the effect of distance. The mother and toddler could have picked a better beach. Although all the beaches along this shore have some rubbish, some have less seaweed, and fewer stones. This beach is not good for paddling, but perhaps it is good for oysters. Yes, the seaweed the rubbish the smell the stones must all be part of the environment oysters prefer, which must be the reason the oyster restaurant is here, allowing the customers seated at the tables to look out at the beach and the sea and, looking, to understand that it must be the environment natural to oysters, and to approve.

Because he has chosen to sit at a table looking out at the sea, in order to see and approve the environment natural to oysters including the seaweed the rubbish the seagulls the stork the stones the mother and the toddler, he cannot signal to the waitress and it is because of this, or because she is insufficiently attentive, or because the oyster bar employs insufficient staff during the busy summer season, that the waitress does not arrive with his order.

He says,

‘Maybe they will bring the entire order at once, though I would have thought they would bring the drinks first.’

He says,

‘They do not have enough staff.’

They employ the number of staff they can afford to employ and serve at a pace at which the staff is capable of serving. The capacity is natural and proportionally correct. Il faut attendre.

He says,

‘They have too many tables.’

We must also consider the number of staff the restaurant can afford to retain over the winter months, which we hope may remain steady although the population of the island must shrink by—what?—fifty—what?—seventy per cent—and during which the catch of oysters may remain the same or may increase because the winter months are more likely to contain the letter ‘r’, during which it is said oysters are best eaten, since during their spawning season, which is typically the months not containing the letter ‘r’, theybecome fatty, watery and soft, less flavourful than those harvested in the cooler, non-spawning months when the oysters are more desirable, lean and firm, with a bright seafood flavour, so that, although all the tables in the restaurant will not be filled in those winter months during which the population of the island shrinks by—what?—forty-five—what?—eighty per cent—we may hope that the number of serving staff employed by the restaurant will remain steady.

Theories:

During the off-months for the visitors, which are the on-months for the oysters, are the oysters packed in ice or tinned and shipped to Paris?During the off-months for the visitors, which are the on-months for the oysters, do the serving staff shuck shells?Or

During the off-months for the visitors, which are the on-months for the oysters, are the restaurant and the oysters abandoned, and the staff laid off?The waitress passes our table again. She does not stop.

He says, ‘I think these are summer staff. They don’t know what they’re doing.’