6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

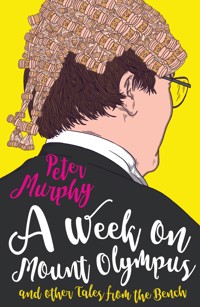

When Charlie Walden took on the job of Resident Judge of the Bermondsey Crown Court, he was hoping for a quiet life. But he soon finds himself struggling to keep the peace between three feisty fellow judges who have very different views about how to do their job, and about how Charlie should do his. And as if that's not enough, there's the endless battle against the 'Grey Smoothies', the humourless grey-suited civil servants who seem determined to drown Charlie in paperwork and strip the court of its last vestiges of civilisation. No hope of a quiet life then for Charlie, and there are times when his real job - trying the challenging criminal cases that come before him - actually seems like light relief.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

WALDEN OF BERMONDSEY

When Charlie Walden took on the job of Resident Judge of the Bermondsey Crown Court, he was hoping for a quiet life. During his short walk from the vicarage to court, there’s a latté waiting at Elsie and Jeanie’s archway café, and The Times at George’s news stand. After a hard day of trial, he and the Reverend Mrs Walden can enjoy a curry and a couple of Cobras at the Delights of the Raj, or a pasta with a decent valpolicella at La Bella Napoli. But a quiet life? Well, not exactly…

Charlie soon finds himself struggling to keep the peace between three feisty fellow judges who have different views about how to do their job, and about how Charlie should do his: Judge Rory ‘Legless’ Dunblane, a proud Scotsman and former rugby player who takes what he likes to think of as a no-nonsense approach to judging; Judge Marjorie Jenkins, judge and super-mum, a brilliant lawyer with a whiz-kid husband in the City, the queen of the common sense approach to the job; and Judge Hubert Drake, nearing retirement, with a host of improbable stories about judges and trials past, and representing an approach from a bygone age – namely, that of the Raj.

And as if that’s not enough, there’s the endless battle against the ‘Grey Smoothies’, the humourless grey-suited civil servants who seem determined to drown Charlie in paperwork and strip the court of the last vestiges of civilisation, such as the notorious court canteen. With the connivance of his list officer, Stella, Charlie wages a stealthy rear-guard action against their relentless attacks, but the Grey Smoothies never go away.

No hope of a quiet life for Charlie, and there are times when his real job – trying the challenging criminal cases that come before him – actually seems like light relief.

About the author

After graduating from Cambridge University Peter Murphy spent a career in the law, as an advocate and teacher, both in England and the United States. His legal work included a number of years in The Hague as defence counsel at the Yugoslavian War Crimes Tribunal. He lives with his wife, Chris, in Cambridgeshire.

FOREWORD

By HH Judge Nicholas Hilliard QC

The Recorder of London

I remember speaking to Peter Murphy when I first learned that he was writing novels which would draw on his many years of experience in the criminal courts. I asked him to be merciful in his portrayal of the Resident Judge. I had an interest of my own because I was at the time the Resident Judge (‘RJ’) at Woolwich Crown Court and Peter was one of the judges there. I had no idea that he was in fact contemplating a whole book written from the RJ’s perspective.

Peter is of course perfectly placed to write these stories because he moved on from Woolwich to become the RJ at Peterborough. The job title is rather misleading. As readers will discover, the fictional Judge Charlie Walden no more lives at Bermondsey Crown Court than any other RJ lives at their court centre. But the RJ is a permanent presence and runs the operation, and all this combines to provide some rich seams, over and above the particular drama of the courtroom, which Peter has artfully mined. We place a high value on judicial independence, and running anything which involves judges as participants provides plentiful opportunities for individuals to come into conflict with ‘group think’.

Peter has recorded it all with an accurate eye and an authentic ear. In doing so, he has created a series of interesting characters and highly entertaining narratives. And Charlie Walden, hard-pressed but invariably well-meaning in the face of conflict and dilemma, deserves a place in the pantheon of fictional legal figures. Of course, I have no doubt that, as always, any resemblance to actual people and events is at least meant to be entirely coincidental.

So I am glad that Peter has been kind to the RJ. I very much hope that Charlie Walden agrees and may perhaps be persuaded to share some more of his experiences in the future. I am only sorry that the Old Bailey where I am now the Resident Judge sometimes manages to irk him just a little. I shall see what I can do in case there is a further instalment.

Nicholas Hilliard

Recorder of London

Central Criminal Court

WHERE THERE’S SMOKE

Monday morning

At about 8 o’clock on a brisk, clear October evening, Father Osbert Stringer, parish priest of the Anglican church of St Giles, Tottenham, and a confirmed bachelor, was in the kitchen in his vicarage enjoying his supper: a cheese omelette and home fries, washed down with a bottle of Old Peculier. The vicarage is next to the church, on its south side. According to his witness statement, Father Stringer happened to look out of his kitchen window and thought he noticed flashes of light coming from the direction of the church. Moments later he thought he saw smoke, and moments after that, he thought he heard a loud noise, as in heavy objects falling to the ground. Leaving the remains of his omelette, he rushed out of his back door, only to see, to his horror, flames inside the church. He immediately called 999. By the time the fire brigade brought the fire under control, the interior of the church was gutted, with the loss of all the furniture and effects inside. There were serious questions about the stability of the whole structure and it was clear that it would not be usable again for a very long time, if ever.

Fortunately, no one was using the church at the time. It was a Wednesday, and usually there would have been choir practice, but it had been cancelled. The church was generally considered an architectural monstrosity both inside and out, and was not greatly mourned. It was also fully insured. The charitably-inclined nearby Methodist church offered accommodation to Father Stringer’s congregation. So it could have been worse.

But in his witness statement, Father Stringer also said that as he ran out of the vicarage he distinctly saw a young male running from the church into the street, throwing away some kind of metal can as he did so. The police later recovered the can, which contained white spirit, a highly flammable substance often used as an accelerant. The spectre of arson raised its head. Arson investigators turned their attention to the church, and quickly found evidence of the use of an accelerant at three different sites within the church. These sites appeared to be the points from which the fire had spread.

The police were, naturally, anxious to know whether Father Stringer had recognised the young male he saw running away. He had. He told the police that the culprit was Tony Devonald, nineteen years of age, a local lad. Tony’s family were members of Father Stringer’s congregation, and he knew the young man well. Tony was arrested later the same evening, and when interviewed under caution, admitted that he had been in the vicinity of the church at about eight o’clock. He told the police he was there because he had received a call at home from a man whose voice he did not recognise, telling him that Father Stringer needed his help with something at the church. When he arrived at the church, he immediately saw the fire. He ran to the south door, the door nearest to the vicarage, which he found unlocked. He called out, but no one replied. He saw a metal can standing by the door. He picked the can up, and noticed that it smelled strongly of white spirit. Seeing no lights in the vicarage, he ran from the church with the intention of summoning help, and took the can with him to ensure that it was out of reach of the flames. He dropped it by the side of the road. He was unable to call for help because he did not have his mobile with him, but he heard the sirens of the approaching fire engines, and went home. He gave no explanation for failing to remain on the scene to talk to the police or the fire brigade about what he had seen. But he insisted that he had nothing to do with starting the fire.

A forensic examination of Tony’s clothing revealed evidence of contact with the same accelerant as used to start the fire in the church, and his fingerprints were found on the can, though not on any item inside what was left of the church. No scorch marks or soot were found on any of his clothes, and there was no smell connected with the fire other than the white spirit. A few days later Father Stringer formally identified him at a properly conducted identification procedure at the police station. He was charged with arson, being reckless as to whether life would be endangered, a very serious offence carrying a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. The magistrates sent the case to the Crown Court for trial. Its natural home would have been the local Wood Green Crown Court, but someone at Wood Green thought that there might be too much local feeling around Tottenham for there to be a fair trial, on which rather pathetic pretext – way over the top, if you ask me – they passed it on to us; which is when it started to get interesting.

But before I go any further, I ought to introduce myself. Charles Walden is the name, Charlie to my family and closest associates. I admit to having passed sixty a couple of years ago. I have been a circuit judge for about twelve years, the last four of which I have spent at the Bermondsey Crown Court as the RJ – Resident Judge. According to the job description, an RJ is a judge who takes on the overall administrative responsibility for the work of all the judges at a court, in addition to his or her own work. In fact, the RJ’s main role is to be the person to blame whenever something goes wrong. When I say ‘something goes wrong’, I mean that the Grey Smoothies think we could be doing whatever it is more efficiently than we do.

The ‘Grey Smoothies’ is the name we have adopted at Bermondsey to refer to the civil servants who oversee the working of the courts. The name derives from the standard grey office suits they wear, and from their infuriatingly self-assured belief in their own infallibility, which continues undiminished despite their tenuous grip on reality when it comes to what is actually going on in the courts. The Grey Smoothies think, speak and write in a language of their own, which bears a passing resemblance to English, but not to any form of English used by normal people. For example: they refer to anyone to whom they write as ‘stakeholders’ in whatever it is they are writing about. Instead of ‘doing’ something, they ‘action’ it. Instead of communicating information to others, they cause it to ‘cascade down’ on them. Instead of starting a project, they ‘roll it out’, or ‘deliver it’. Any project not to be rolled out immediately – for example because ‘the jury is still out on it’ – is ‘parked’. And then, of course, there are the two most important expressions in Grey Smoothie vocabulary: ‘business case’ and ‘value for money’. Most Grey Smoothies find it difficult to compose a sentence without using one or both of those expressions.

Their charge that we could be doing things more efficiently than we do is, of course, perfectly true; and if they gave us the staff and equipment we need, we would do better. But questions of staff and equipment are prime business case territory, in which the Grey Smoothies reign supreme. They govern this territory using a form of magical thinking, according to which the courts should be able to function just as well, regardless of how little they give us in the way of money and resources, if only we would all just get on with it and work hard enough. So, the sad truth is that the necessary staff and equipment will not be forthcoming at any time before the ravens leave the Tower of London, or the apes leave the Rock of Gibraltar, whichever is the later.

When confronted with this reality, the Grey Smoothies get very defensive, and retaliate by demanding endless statistics: how many cases have been disposed of? Were any of them trials which collapsed at the last moment? What is the average time for every kind of case to be heard? How many hours a day did each court sit? What was the reason for any short days? How many jurors did we summon, and how many attended? How long did they wait to be assigned to a trial? And there is a statistical survey form for every sentence we pass. About the only thing they haven’t asked yet is how much time we spend in the loo. We expect that request at any moment.

The court staff and I could easily spend almost every hour of our days buggering about with this nonsense, in which case, of course, there would only be one statistic, namely that the court has no time to do anything except compile the bloody statistics. So in cahoots with our list officer, Stella, I devised Bermondsey’s defence against attacks of the Grey Smoothies soon after I took up residence. The defence is that we basically ignore them. This obviously annoys the Grey Smoothies, and eventually I get an irate email from a presiding High Court judge for the Circuit telling us to pull our fingers out; at which point Stella and I fabricate a few reasonable-looking numbers for them, which seems to keep them happy for a while. We are particularly proud of having the third worst record in the country for returning the sentencing survey forms; we have managed to get it down below twenty per cent. At least, this way, I have time to be a judge.

In mitigation I wish to point out that, in return for shouldering the administrative burden of the court, the RJ receives no extra remuneration, no extra recognition, and no administrative assistance whatsoever. It’s a miracle that anyone ever agrees to do it. Some get bullied into it by the presiding judges. Others do so in the hope that it will give them an eventual leg up to the High Court or even the Old Bailey; and yet others out of a sense of duty. In my case, the reason is simpler. I wanted to sit at Bermondsey because it’s an easy commute to and from work, and the only vacancy at the time was for an RJ; so being RJ was the price I had to pay.

You see, my good lady wife, the Reverend Mrs Walden, is priest-in-charge of the parish of St Aethelburgh and All Angels in the Diocese of Southwark. Being priest-in-charge is just like being an RJ, really, but with different robes. Her living carries with it the privilege of residing in a huge Victorian vicarage which has many fine architectural features; a large weed sanctuary, euphemistically referred to as a garden, at the rear; and no modern amenities whatsoever. It is hot in summer and freezing in winter, and generally looks as though it has not been decorated since the First Boer War. And with both our daughters having long since flown the nest to make their way in the world as single career women, it is a fair bit bigger than we need. But it is close to work for us both, and I enjoy my short stroll to court in the morning.

Along the way I stop at a coffee and sandwich bar run by two ladies called Elsie and Jeanie. The bar is secreted in an archway under the railway bridge, not far from London Bridge station, and it gets crowded if they have more than two customers at a time. But they do a wonderful latte, and a nice ham and cheese on a bap – a temptation if, as is often the case, I’m not relishing the thought of the dish of the day in the judicial mess. The only downside is that I have to listen to their various woes while the process of latte-making is going on. Elsie has a couple of grandchildren who get themselves into occasional scrapes with the law, about which I have to be non-committal because I may well see them at Bermondsey one of these days. Jeanie has a husband who seems to spend most of his time, and most of his benefits, at the pub and the betting shop. So, one way or another, they are rarely short of things to grumble about, and they usually take full advantage. Next door to Elsie and Jeanie is George, the newsagent and tobacconist, from whom I collect my daily copy of the Times. George has never quite forgiven me for giving up smoking two years ago, since when he has been unable to sell me cigarettes as well, but he is usually prepared with my newspaper, a cheerful greeting, and a penetrating insight into the shortcomings of the Labour Party.

Sitting in my chambers waiting for the trial of Tony Devonald to begin, I am reminded of why I decided to write down some of my experiences and reminiscences as RJ. As much as anything, it is to keep my mind occupied during the long periods of each day when I am sitting around waiting for something to happen. Why would a judge be sitting around waiting for something to happen? I hear you ask. The Grey Smoothies ask the same question. Let me count the ways.

The prison van breaks down, so they can’t bring the defendant to court. The prison officers haven’t bothered to read the daily court list, so they don’t know that the defendant’s attendance is required. The court’s recording equipment, essential for making a record of the proceedings, isn’t working. The video equipment, essential for playing CCTV footage to the jury, isn’t working. Alternatively, the video equipment, essential for playing CCTV footage to the jury, is working but is not compatible with the DVD. The defendant is on bail and hasn’t turned up. The interpreter hasn’t turned up. Counsel is stuck on a train somewhere, or is double-booked. We don’t have enough jurors, and can’t begin a trial until a jury returns with a verdict in another court. I could go on. There are times when it is a bloody wonder we get anything done at all. How is that for a statistic? So rather than just sit here feeling my blood pressure rise, I have decided to tell a few tales about life at Bermondsey Crown Court, in the hope that we can all happily while away the hours together.

This morning, I am told that the prosecution have forgotten to warn Father Stringer that he would be required as a witness today, and he is not available until two o’clock. I grab a jury panel before anyone else can snatch them all away. We quickly select a jury at random from a panel of the good citizens of Bermondsey, and I explain to them that they are not allowed to conduct any inquiries of their own into the case, such as doing internet searches about the events or the people involved; or discussing the case with anyone outside their number; or doing anything else any rational person would naturally be inclined to do in this electronic age. There is no way to tell whether juries obey these directions, except in the rare case where a juror is stupid enough to talk about his or her research and gets done for contempt. But we have to try. The evidence in most criminal trials is dicey enough as it is, without contamination from internet sources that can’t be checked. But reaching for the nearest laptop or tablet is as much an instinctive human reaction these days as raising a spear to a sabre-toothed tiger, and I suspect that once you tell a jury not to take to the internet, it is a hard temptation for them to resist.

I then release the jury until after lunch. Fortunately, the morning is not entirely wasted. Stella has found me a sentence to do. Stella is in her early forties and what we call, in the judicial mess, MFX – married but whatever you do, don’t bring up the subject of family. She favours blouses and slacks in autumnal colours regardless of the season, and has short-cropped straw-coloured hair. And she is absolutely bloody brilliant. The job of list officer is an extraordinarily difficult one, calling for a high degree of organisation and planning. She has to list trials, sentences, and other hearings for four judges. This means looking months ahead in the diary, predicting which trials will fold and go short; negotiating with the CPS – the Crown Prosecution Service; fending off pushy solicitors and counsel’s clerks; factoring in the absence of judges and staff who are away on leave; and generally keeping the court’s workload moving forward. There are many days when a crystal ball would be just as useful as the administrative skills. Stella excels at the job, almost as if she had been born to it. But she does have an air of perpetual anxiety, as if she is always anticipating disaster around the next corner. For a list officer, this may simply be a realistic approach to life, because there is a lot that can go horribly wrong, but it tends to make me nervous whenever she appears in my chambers. Under Stella’s influence, I have become accustomed to expecting the worst.

My colleague Marjorie Jenkins was supposed to do the sentence, but another matter she has in her list has turned out to be more complicated than thought, and she is anxious to start a trial. It doesn’t take long. The defendant, a native of a foreign country in his late thirties, turned up at a bank with a false passport, which he tried to use for identification purposes to open an account. These days, banks and cash converters and the like can spot false passports a hundred yards down the street on a foggy day. They seem to have some kind of homing device for them. It is almost uncanny. Without the benefit of ultra-violet light and all the rest of it, they do just as good a job of weeding them out as the Border Agency. The bank called the police. Chummy made an immediate confession and pleaded guilty as soon as he had the chance. He entered the UK on a student visa three years ago, and is an overstayer. He is of previous good character, and has been working hard at various cash-in-hand jobs to make ends meet for himself, his partner (also an overstayer) and their four-year-old daughter. He was offered a much better job recently, but it was one for which he needed a bank account to receive his salary. An acquaintance offered him the false passport, with an endorsement for indefinite leave to remain in the UK, for twelve hundred pounds. Foolishly, he accepted it. Now, it’s not to be. Regardless of what I do, Chummy will be deported. I give him the usual four months, allowing him a third off for his early plea. It’s a standard result. We do several of these a month. I disdainfully deposit the sentencing survey form, unsullied by my pen, in the waste paper basket.

And so to lunch, an oasis of calm in a desert of chaos.

The judicial mess – what normal people would call the judges’ dining room – is a rather small space, almost all of which is taken up by a huge circular table and correspondingly huge chairs. If you were planning this room from scratch, you would opt for a much smaller table. But it was free, surplus to requirements from the Ministry of Work and Pensions some years ago, so our court manager, Bob, took possession of it without worrying about details such as the size of the room. Free is a big thing with Bob, whose previous career had something to do with fund-raising for a theatre company, and much of our court management seems to depend on largesse and cheap solutions, including the recording and video equipment I referred to earlier. We have just about managed to squeeze in a small sideboard in the corner, on which there is just about room for the coffee machine.

The mess leads directly into the kitchen. As for the food, the less said the better. The official line is that the caterers do their best with a limited budget. Perhaps they do, but the thought of the jury, advocates, and court staff – not to mention the judges – putting their lives on the line each day in the court canteen or the mess is disquieting. The main area of risk is the dreaded dish of the day, which may be advertised as anything from lasagne to curry to fish and chips. Slightly safer are the omelettes, salads, and baked potatoes, which we judges tend to prefer on the assumption that there is less potential for things to go wrong. But there are many days when Elsie and Jeanie’s ham and cheese seems the best option to me. Regardless of the food, lunch is important. It is usually the only chance we get to talk and pick each other’s brains during the day.

As I am the last to arrive today, I take the seat just inside the door. There is just about room for the door to close behind the rear legs of my chair.

To my left is Judge Rory Dunblane, early fifties, tall with sandy hair, a proud Scotsman, still plays a good game of squash and still enjoys his nights out with ‘the boys’ (whoever they may be). Divorced for almost a decade, he has a bewildering succession of girlfriends, none of whom seem to last very long. No one calls him Rory. He has been known to all as ‘Legless’ for as long as I have known him, and that is quite a while now. The nickname dates back to an incident during his younger days while he was at the Bar, something to do with the fountains in Trafalgar Square after a chambers dinner. No one, including Legless himself, seems to remember the details of the incident, but the name has stuck. Legless is what you would call a robust judge, who likes to get through his workload without any nonsense.

Opposite me is Judge Marjorie Jenkins, slim, medium height, dark hair and blue eyes. In her mid-forties, she has been on the bench for five years already. When she was appointed, Marjorie was an up-and-coming Silk doing commercial work, representing City banks and financial institutions, and everyone was surprised that she took what, in her world, would be seen as a menial job. Marjorie is what they used to call a super-mum, a perpetual motion machine who balances a high-powered career with her family and various voluntary works. Her husband Nigel speaks six languages fluently and does something very important for an international bank. They spend holidays in Provence, where they have a house, or in Lausanne or Rome or Cape Town, as the muse leads them. Their two children, Simon and Samantha, are away at boarding school. It seems to be generally assumed that becoming a circuit judge is a kind of career break for Marjorie, and that she will resume her upwardly mobile path once the children are older. She does tend to disappear without much warning if anything goes wrong at school. But she is a great asset, particularly for fraud cases, in which she effortlessly assimilates tons of material which would take the rest of us weeks even to read, let alone digest.

To my right sits Judge Hubert Drake. Hubert is a bit of a problem, mainly because no one is sure exactly how old he is. Apparently, the official records have him down as sixty-six, but I would bet good money that the train left that station some time ago. As far as I can tell, he is still all right in court. The Bar complain about him as being too right-wing and reactionary – which he accepts, and regards as an accolade – but I am not yet hearing that he is losing the plot. Nonetheless, I have a nasty suspicion that it is only a matter of time. As to judicial style, Hubert would have made a first rate colonial magistrate in India in the days of the Raj. He has been widowed for some years. He has a nice flat in Chelsea, and divides his time more or less equally between the flat and the Garrick Club. My main worry is that he is determined never to retire, and he says they can’t make him. When he reaches retiring age they can in fact make him, and I have nightmares about the scenes we will have when that happens.

‘Thanks for taking my sentence, Charlie,’ Marjorie says. ‘Any problems?’

‘No,’ I reply. ‘Bog standard false passport to open a bank account. I gave him the usual four months on a plea, and he will be departing our shores before too long. Keep the Home Secretary happy.’

‘Should have been two years,’ Hubert mutters, looking up briefly from his lamb jalfrezi, the guise in which today’s dish of the day presents itself.

‘That’s a bit over the top, isn’t it, Hubert?’ Legless asks.

‘Certainly not,’ Hubert replies. ‘Too much of that kind of thing going on, by far. It’s about time we did something about it.’

We allow the subject to drop. We have tried to take Hubert on about his attitude to sentencing in the past, and it’s usually not very successful.

‘Can I get some advice on something?’ Marjorie asks. ‘I’ve got an actual bodily harm. Chummy says it was self-defence. It all happened at a rugby match. Apparently, Chummy and the complainant were on opposing teams, one of them a loose head and one a tight head, whatever the hell that means. Counsel did try to explain it to me, but it didn’t make much impression. Anyway, the two of them got into a fight towards the end of the match, and the complainant ended up with a broken nose, a broken tooth, and some cuts and bruises. The question is whether –’

‘Chummy was charged with ABH just for that?’ Legless interrupts, aghast. Legless played a bit at outside centre for Rosslyn Park during the amateur era, and still takes himself off faithfully to Murrayfield for internationals during the Six Nations.

‘The referee was an off-duty police officer,’ Marjorie explains. ‘It happened right in front of him and he didn’t think he could ignore it.’

‘You see, this is the kind of nonsense that’s killing the game,’ Legless protests. ‘You can’t have a bloody rugby match without the odd fight. It’s part of the game. You shake hands in the bar afterwards and buy each other a pint, and that’s the end of it.’

‘Not when there is a serious injury, surely?’

‘It doesn’t sound very serious. In any case, you said he was only charged with ABH.’

‘Be that as it may,’ Marjorie insists, ‘he was charged and I have to try it. The question is, whether the prosecution are allowed to tell the jury that Chummy had already received two yellow cards during the same season.’

‘You mean, as evidence of bad character?’ I ask, ‘evidence of propensity to be violent?’

‘Exactly.’

We all ponder this jurisprudential conundrum for some time.

‘Well, yes, I should have thought so,’ I offer.

‘No, not necessarily,’ Legless counters. ‘It all depends on why he got the yellow cards.’

‘Presumably for beating up someone else,’ Marjorie says, ‘a hooker, or whatever you call them.’

‘You can’t assume that,’ Legless replies. ‘You can get yellow cards for all kinds of reasons.’

‘Such as what?’

‘Well, almost anything, if it prevents the other side from scoring a try. If you fail to release the ball near your own line, or tackle a man without the ball, and the other side would have scored, you will get a yellow card.’

‘So, I should ask for evidence about what the cards were for?’

‘Absolutely. They may not be relevant at all.’

Marjorie nods. ‘Right, thank you.’

But Legless is still shaking his head.

‘I wouldn’t let it go to trial,’ he insists.

Marjorie laughs. ‘How can I stop it?’

‘It’s a question of consent,’ he replies. ‘When you agree to play in a rugby match, you consent to a certain amount of violence. You can’t then complain about it afterwards.’

‘But only in accordance with the rules of the game, surely?’ I ask.

‘The rules of the game make the odd fight inevitable,’ Legless replies. ‘It’s what rugby is all about. That’s why people go to watch it. If it’s nothing worse than a broken nose, it’s a case for a pint, and perhaps a suspension for a game or two. But that’s it.’

‘But according to the House of Lords in Brown,’ Marjorie says, ‘you can’t consent to injury at the level of ABH or more serious.’

That’s the kind of thing Marjorie would know, without even looking in Archbold.

‘Well, tell the prosecution to reduce the charge to common assault, and give him a conditional discharge,’ Legless pleads.

‘Thanks for the help,’ she replies. ‘Must rush.’

‘Why didn’t Stella give that case to me?’ Legless asks plaintively after Marjorie has departed. ‘I know all about the kind of things that happen in rugby matches. I would have sorted it in no time.’

I know the answer to that question, but I’m not about to tell him. There are few people more dangerous in this world than a judge who thinks he has some personal insight into the subject-matter of the case. They tend to ignore the evidence and substitute what they think they know. Far better to have a judge who is totally ignorant of subject-matter, and has no choice but to rely on the evidence. Stella and I decided long ago that Marjorie was getting this one.

‘I can’t imagine,’ I reply.

* * *

Monday afternoon

When I said that the case of Tony Devonald had become interesting, what I meant was this. With any case of arson, you are going to need a psychiatric report at some point. Arson is a very strange offence, almost always committed by very strange people. I have always found it helps to have a report sooner rather than later. Legless ordered one when the case first came to us from Wood Green, and it is in my file. It was prepared, as usual at Bermondsey, by our local shrink, Dr Mohammed Rashid. Like all psych reports, it goes on at great length about the defendant’s history from conception onwards, his relationship with his parents, his history at school, his employment record, any personal relationships, any involvement with drink or drugs, and so on and so forth. Even for someone of Tony Devonald’s tender years, it runs to some thirty-five pages. Following my usual practice, I turn first to the conclusions at the end of the report, intending to skim the rest later to the extent necessary, if I have time. The conclusions are contained in paragraph 52, which states, intriguingly:

Despite the incidents referred to in paragraph 34, I have found no evidence that Tony is suffering from any psychiatric illness or personality disorder. He is fit to stand trial, and if convicted, to be sentenced as the court may think appropriate.

Naturally, I turn back with some interest to paragraph 34, in which Dr Rashid has recorded the following.

Both Tony and his father described an occasion on which the father consulted their parish priest, Father Stringer, because of a concern that Tony might have been the subject of some form of demonic possession. Apparently, the family was concerned that some objects, such as knives and forks, appeared to move along the dining table of their own accord while Tony was seated at the table. This concern appeared to rest mainly on the observation of Tony’s six-year-old sister Martha. Also, there was an occasion when a small fire began mysteriously in the garage one morning shortly after Tony had stormed out of breakfast following an argument with his mother, though the mother spotted the fire and it was extinguished without difficulty, no damage being caused. Tony told me that Martha must have been mistaken, and that he has no supernatural power to move objects without touching them. He also denied setting a fire in the garage. He said that, on Father Stringer’s insistence, he permitted the priest to pray with him in St Giles’s church, a process he considers to have had no effect at all. He told me that he has no particular feelings about Father Stringer or the church one way or the other, and he vehemently denies setting fire to the church.

I sit and ponder this for some time while waiting to go into court. I thumb through the file. I don’t expect the prosecution to mention it. The prosecution hasn’t made an application to allow evidence that Tony had set other fires, and the evidence linking Tony to the garage fire seems a bit vague, to say the least. Quite apart from that, demonic possession is something we try to avoid at Bermondsey whenever possible. My court clerk, Carol, comes to tell me that court is assembled. Carol is in her fifties. She is amazingly good at her job, has a frightening grasp of detail, and she seems to love every moment she spends in court. Her other passion in life is football. She and her husband Ray never miss a home game at Millwall and I usually hear all about it on Mondays. They lost at home to Blackburn Rovers on Saturday, so her mood today is a bit low.

As I enter court I see Tony Devonald directly in front of me in the dock. He is a thin, frail-looking lad. He is wearing a suit which doesn’t fit him terribly well, and a crumpled shirt and tie. I wonder why his parents haven’t done a better job of getting him turned out properly for court. He looks very nervous.

I look down towards counsel. Roderick Lofthouse is prosecuting. He might be just what the case needs if we are going to get into demonic possession. I don’t mean that the way it sounds. Roderick is generally regarded as the doyen of the Bermondsey Crown Court Bar, which is a polite way of saying that he may have been around for just a little too long. He takes advantage of his seniority to wear a two-piece grey suit which is rather too light in colour for court and about half a size too small, the jacket remaining closed rather precariously, relying on a single overworked button. He is not always as well prepared as he should be these days, relying on his instinct for a case, rather than on reading the papers, as his main method of preparation. But he is always calm and has sound judgment. He won’t get flummoxed or carried away, whatever happens. Defending is Cathy Writtle, small and energetic, with disorganised hair and large brown tortoise-shell spectacle frames, who will have read every shred of paper and will know the case inside out. That also is good. Cathy’s only failing is that her default setting is all-out attack, which works better in some cases than others. I’m not sure it is quite the right approach in this case.

Roderick rises ponderously, looking every inch the doyen he is, to begin his opening speech. He is as smooth as ever. He begins by showing the jury the indictment and telling them that the prosecution has the burden of proving the defendant’s guilt so that they are sure, failing which they must find young Tony Devonald not guilty. That’s the way we do things in England, always have, no matter what goes on in other parts of the world. Fine, heart-warming stuff. Next he explains what arson is, intentionally starting a fire, keep it simple. So far, so good. But then, he accounts for the element of recklessness about endangering life by claiming that, for all the defendant knew, the members of the choir might have been in church that evening, as they usually would on a Wednesday. Now, as the fire was set inside the church, and it would take a rather careless arsonist not to notice an entire choir belting out ‘O God, Our Help in Ages Past’to the accompaniment of a pipe organ, this strikes me as not the most persuasive of arguments. Cathy Writtle apparently agrees. She ostentatiously raises her eyebrows, not quite directly at the jury, but in such a way that they could hardly miss the gesture. We haven’t heard the last of that.

The consequences of the fire, Roderick continues, were very serious even as things were, but at least it was only property damage; no one was killed or injured. He describes the extent of the fire, and the forensic findings about how and where it started and spread. He describes Father Stringer running from his cheese omelette, home fries and Old Peculier to summon help. He relates Father Stringer’s identification of Tony Devonald as the young man running away from the church and discarding a can later found to have contained an accelerant. He concludes by giving the jury details of the defendant’s arrest and interview and announces that he will call Father Osbert Stringer.

It’s an odd case in a way, I reflect. The issue is not really one of identification. Tony Devonald admits to having been in the vicinity of the church, and claims to have been running to get help. No one saw any other potential culprit. Roderick hasn’t mentioned any inquiry into the phone call Tony claims to have received summoning him to the church, even though the police seized his mobile when he was arrested.

‘Father Stringer, how long have you been in holy orders?’

‘For more than thirty years.’

Stringer is a small, wiry man. It’s hard to guess his age, except that for some reason he looks closer to sixty than forty. He has thinning white hair, a white moustache, and a neatly trimmed white beard. Everything else about him, the full-length cassock, belt – and the eyes – are solid black. There is a definite touch of the Rasputin about him. Instead of looking at Roderick Lofthouse, he fixes the jury with a stare which has one or two of them shifting uncomfortably in their seats.

‘And for how long have you been vicar of St Giles?’

‘For about four years.’

‘Let me take you to the evening in question, the evening when your church was burned. Do you remember that evening?’

Oh, come on, Roderick, I think, no prizes for the answer to that one. But it is interesting: I look at Stringer, and I can’t detect any emotion in the reply at all.

‘I remember it very well.’

‘Where were you at about eight o’clock on that evening?’

‘I was in the kitchen at the vicarage, having dinner, an omelette and chips.’

‘Was anyone else in the vicarage at that time?’

‘No. I live alone.’

‘And, to your knowledge, was anyone in the church?’

‘No. The choir should have been there practising, but the practice had been cancelled.’

‘For what reason, do you remember?’

Hesitation.

‘No. Offhand, I can’t remember.’

‘Did anything come to your attention at about eight o’clock?’

‘Yes. I happened to look out of the kitchen window, and I saw what at first seemed to be a bright light coming from inside the church, close to the altar. Almost immediately, I saw smoke drifting towards the vicarage, and then flames inside the church. I knew then that the church was on fire.’

‘What did you do?’

‘I ran outside at once, taking my phone with me, and called the fire brigade.’

‘As you were running outside, were you aware of anyone else?’

‘Yes. I saw a figure running away from the church towards Vicarage Road.’

‘Can you describe this figure?’

‘Male, young, late teens to early twenties, wearing a dark jacket and jeans, dark short hair, about five-seven, five-eight.’

‘Father Stringer, I think that a few days later you made a formal identification of the person you saw, by identifying his image as number six in an array of nine you were shown at the police station, is that right?’

‘That is correct.’

‘Was this person also known to you before that occasion?’

‘He was very well known to me. It was the defendant, Tony Devonald. He and his parents are my parishioners.’

‘How sure are you of your identification?’

‘One hundred per cent.’

‘Thank you, Father. Did you notice whether the figure you saw had anything with him?’

‘Yes, he was carrying what I later saw was a metal can.’

‘Later saw?’

‘He threw the can away on the ground as he was running away. Once I had called the fire brigade, I went to look at it.’

‘Can you describe it for us?’

‘It was a large metal can, silver in colour.’

‘Did you notice anything else about it?’

‘It smelled strongly of white spirit.’

Roderick turns around to the officer in the case, who hands him an object contained in a large, heavy-duty plastic evidence sack, bearing various labels.

‘With the usher’s assistance…’

The usher today is Dawn, a thirty-something brunette who always wears bright colours under her black usher’s robe. She is the court’s resident expert on home remedies, and is our trained emergency first aid person. Dawn takes every verdict of not guilty as a personal affront. ‘Oh, Judge, after all that work,’ she sometimes says sadly once we are alone in chambers, reflecting on the loss of some defendant I have just discharged, for no better reason than that the jury were not sure of his guilt. Dawn walks brightly over to Roderick, relieves him of the package and, needing no further bidding, makes her way to the witness box to show it to the vicar.

‘That appears to be the can I saw,’ he confirms.

‘May that be exhibit one?’ Roderick asks. I assent. Dawn passes the exhibit around the jury, so that they can see the tool of the dastardly act at close quarters and be suitably horrified. They don’t look too impressed.

‘How long did it take the fire brigade to arrive on the scene?’

‘They were there very quickly. No more than ten minutes at most.’

‘Did they succeed in extinguishing the fire?’

‘Eventually. But by the time it was brought under control there was virtually nothing left inside the church.’

‘So the church lost…?’

‘All the furniture, the paintings, statues, the silverware on the altar, my vestments, prayer books, hymnals. There was nothing left, really. I didn’t discover the extent of the loss until two days after the fire. They wouldn’t let me back inside until they were sure the structure was safe.’

Once more there is no display of emotion at all. Just the facts.

‘Finally, Father, have you been able to use the church since then?’

‘No. The church has received funds from our insurers, but the work will occupy a considerable time. We are enjoying the hospitality of our Methodist friends for the foreseeable future.’

Roderick invites Father Stringer to stay where he is, in case there are further questions. There will be further questions; you can bet your pension on that. Cathy Writtle is already on her feet.

‘You were having dinner, when you noticed the fire, were you, Father?’

‘I was.’

‘A cheese omelette and chips?’

‘I don’t see what that has to do with it.’

‘Neither do I. But you gave the jury the menu when my learned friend asked you what you were doing.’

‘Did I? Well, perhaps I did.’

‘What you didn’t mention was the bottle of Old Peculier you had with it. Does that have nothing to do with it as well?’

‘I can’t see how that would be relevant.’

Neither can I, at present. Cathy’s defence statement says nothing about Rasputin burning the church down accidentally while trying to light a candle under the influence of Old Peculier; and in any case, that scenario wouldn’t entirely account for the presence of white spirit. It may be that Cathy is just engaging in a bit of gratuitous violence against the witness to soften him up. Roderick doesn’t seem concerned enough to object, so I’m not going to stop her unless it gets out of hand.

‘Well, let’s think about that for a moment. Was it just the one bottle you had?’

‘Yes, I think so. Well, it might have been two.’

‘Might it have been more than two?’

‘No. I don’t think so.’

‘You don’t think so?’

‘No. I am sure it was just the two.’

‘Any advance on two? Going once …’

‘Miss Writtle…’ I say.

‘Sorry, your Honour,’ she replies, insincerely.

‘It was just two,’ Father Stringer says.

‘All right,’ Cathy says. ‘Let’s move on to something else. Was it your practice to keep the church locked at night?’

‘It was locked most of the time,’ Stringer replies wistfully. ‘We would have liked to keep it open all the time for prayer and meditation. But in Tottenham, you know… that would just be inviting vandalism. So we kept it locked unless there was a service or a church activity going on.’

‘On this evening, there should have been a choir practice going on, yes?’

‘That is correct.’

‘But for some reason you cannot now remember, it had been cancelled?’

‘Yes.’

‘How many entrances are there to the church?

‘There are two. The main entrance is by the west door. But there is a smaller door on the south side. Actually, there is also a third door leading, not from the church, but from the vestry directly out into the graveyard on the north side. But it is hardly ever used.’

‘Were these doors locked or unlocked at the time of the fire?’

‘They should have been locked. Perhaps it might be more accurate to say that there would have been no reason for them to be unlocked.’

‘When was the last time you were in the church before the fire?’

‘At about four-thirty that same afternoon. I had left some papers I needed in the vestry, and I went in to get them.’

‘How did you enter the church?’

‘Through the south door, as always.’

‘Did you have to unlock the door in order to enter at that time?’

‘Yes, I am sure I did. If it had been unlocked I would have noticed.’

‘Did you lock the door when you left?’

‘Yes, I am sure I would have locked it.’

‘How many people have keys, apart from yourself?’

Stringer thinks for some time.

‘A number of people have keys. My church wardens, our organist and choir master, the ladies who do the flowers, the cleaners. People need access to the church for various purposes throughout the day.’

‘Did Tony Devonald, or any member of his family, have a key?’

‘No.’

Cathy pauses to allow this to sink in, seeming to consult her notes.

‘Now, you say you saw Tony Devonald when you came out of the vicarage, having seen the fire?’

‘That is correct.’

‘Tony does not dispute that you saw him.’

‘He could not dispute it. I saw him running away.’

‘You saw him running, Father. But you don’t know whether or not he was running away, do you? He could have been running for some other reason, could he not?’

Stringer scoffs.

‘Not when I saw him throwing that metal can away.’

Cathy nods and pulls herself up to her full height.

‘What was Tony wearing?’

‘A dark jacket and jeans.’

‘Gloves?’

‘No, I don’t think so… well, I’m not sure. I didn’t really see his hands.’

‘Well, you did see his hands, Father, didn’t you, if what you say is correct – that he threw down a metal can?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Father Stringer, what you saw was quite consistent with Tony removing the can to a safe distance and then running to get help, isn’t that right?’

‘That is not what happened.’

‘That will be for the jury to say, Father. My question is, whether what you saw was consistent with what I suggested to you?’

‘Not in my opinion.’

‘Very well. Did you phone Tony Devonald that evening to ask him to come to the church for any reason?’

‘Why would I do that?’

‘I don’t know. I’m asking.’

‘No. Certainly not.’

‘Did you ask anyone to make such a call on your behalf?’

Stringer suddenly becomes agitated.

‘Don’t play games with me, young lady…’

We are all a bit taken aback. Cathy looks at me. I prepare to lecture the witness about how to behave in court and tell him to answer the question, when he adds, quite gratuitously –

‘In any case, he’s done it before, hasn’t he? What more do you need?’

There is a long silence. Roderick sighs audibly and looks away. The message he is sending me is: this is down to the witness, nothing to do with me. That is undoubtedly true.

‘Your Honour,’ Cathy says, ‘may I mention a matter of law in the absence of the jury?’

I send the jury and the witness out of court. As far as I am concerned, this has put an end to the trial. The business of the fire in the garage is not admissible evidence, and it is horribly prejudicial. It should not have been mentioned. Tony Devonald is entitled to a fair trial before another jury, and once Cathy makes the request, I am bound to discharge this jury and adjourn the case to another day. The only consolation is that, once Roderick confirms to me that he instructed Father Stringer not to refer to the previous incident, which I am quite sure he did, I can threaten Stringer with proceedings for contempt for deliberately sabotaging the trial. But to my surprise –

‘Your Honour,’ Cathy says, ‘I am not sure how I wish to proceed. I would like to take instructions from my client. I see the hour. Might I ask your Honour to allow me until tomorrow morning to decide whether or not to apply to discharge the jury?’

I agree immediately. It is the least I can do.

On my way out of the building I pass Marjorie’s chambers, and poke my head around the door.

‘Did you get the yellow cards sorted?’ I ask.

‘Partly,’ she replies. ‘One of them was for head-butting a blind-side flanker. So that was easy enough. But the other one was for something called side entry.’

We grimace at the same time.

‘That doesn’t sound very nice,’ I comment. ‘Do you know what it means? Is it anything to do with loose and tight heads?’

‘I’m not sure I want to know.’

‘It sounds like something that deserves an immediate red card, if you ask me. But I am sure Legless would say it’s just part of the game. Haven’t you asked him about it?’

‘He seems to have gone home. I’ll ask him tomorrow.’

‘Try not to think about it too much this evening,’ I advise. ‘It might put you off your dinner.’

* * *

Tuesday morning

Fortified by a large latte, lovingly prepared by Jeanie to the accompaniment of a lament about her husband having invested the rent money in the outcome of the three o’clock at Chepstow, I make my way to chambers. Stella appears moments afterwards, to give me a date for the re-trial of Tony Devonald, and to discuss what she has available to keep me off the streets for the rest of the week. There is a two-day ABH, your typical fight outside a night-club at chucking-out time, which would otherwise go to Hubert. I can scarcely contain my excitement. But when I go into court –

‘Your Honour,’ Cathy says, ‘having considered the matter overnight, and having taken instructions from my client, I do not ask for the jury to be discharged. We would like the trial to continue.’

I nod. ‘Do you want me to tell the jury to disregard the witness’s last answer?’

‘No, your Honour. But I would ask that you instruct the witness to confine himself to answering my questions.’

That will be my pleasure. The jury comes into court. Father Stringer makes his way slowly back to the witness box. He looks rather sheepish. I get the impression that Roderick has already advised him about the error of his ways. To make sure, in the presence of the jury, I remind him that he is still under oath, and, as Cathy has requested, I give him a thorough bollocking and a lecture about behaving himself, on pain of having to show cause why he should not be held in contempt. This appears to have the desired effect.

‘Father Stringer,’ Cathy begins, ‘yesterday afternoon, you told the jury that my client, Tony Devonald, had, quote, done it before, unquote. The jury may be surprised to hear that, given that Tony is a young man of previous good character. Would you care to explain to them what you meant by it?’

The witness is on the defensive now. He senses that no good is going to come of this.

‘Well,’ he begins slowly, ‘there was a time a couple of years ago…’

‘Let me help you,’ Cathy volunteers. ‘Tony’s father came to you and told you a story about knives and forks moving on their own in the Devonald household?’

‘Yes.’

‘And he suggested to you that Tony might have had something to do with that, yes?’

‘Yes.’

‘And he told you that a fire had started in the garage?’

‘Yes.’

‘And he suggested that Tony might have had something to do with that, too?’

‘Yes.’

‘Just a couple of pieces of paper set on fire?’

‘I don’t remember all the details.’

‘No damage was done, and no accelerant was used, is that right?’

‘I…’

‘I am sure my learned friend Mr Lofthouse will correct me if I am wrong.’

‘I have no reason to doubt what my learned friend says,’ Roderick confirms disinterestedly. It is quite obvious that Father Stringer can expect no more sympathy from that side of the court.

‘I will take your word for it,’ Stringer replies sullenly.

‘Thank you. Were you also made aware that the stories about automotive cutlery at the Devonald house came from a six-year old girl?’

‘Yes, I believe so.’

‘A six-year old girl who was also in the house when this rather small fire started? Tony’s sister, Martha?’

‘That may be so.’

‘It was so, wasn’t it?’

‘Yes.’

‘Thank you. Did you interview Martha?’

‘No.’

‘No. Instead, you prayed with Tony, didn’t you? In the church?’

‘I did.’

‘Did he seem to you to be possessed by any demons?’

Father Stringer looks down. He really doesn’t want to get into this.

‘Well, did you notice any demons leave him when you were praying?’

‘No,’ he concedes eventually.

‘No. What did Tony tell you about the fire in the garage?’

‘He said he didn’t know how it started.’

Cathy studies her notes and pretends to sit down, but then pushes herself up again abruptly, giving the impression of having carelessly forgotten her final question. It is an old trick for drawing attention to a question, and she carries it off well.

‘Oh, just one last thing, Father. You told the jury that you could not remember why choir practice had been cancelled. Do you remember telling the choir master, Mr Summers, on that very same afternoon at about one o’clock that it would be inconvenient for choir practice to be held on that evening?’

If Cathy intended to throw Father Stringer off balance, my impression is that she has succeeded.

‘Inconvenient?’

‘Yes. Is that what you told Mr Summers?’

Hesitation.

‘I can’t think of any reason why it would have been inconvenient.’

‘My question was: is that what you told him?’

‘No. Not as far as I remember.’

‘And no reason comes to mind why choir practice should have been cancelled on that evening?’

‘None that I can think of. You could ask John Summers.’

Cathy smiles.

‘Oh, we will. Thank you, Father.’

She sits down definitively. She really has finished now. It was a gutsy call to carry on with this jury and try to turn the demonic possession-based fire-raising into something of a joke; to try to turn it back on the prosecution. What’s more, I think she may have pulled it off. I give her a quick nod of appreciation, and she gives me a sly grin in return. Roderick asks a couple of completely pointless questions in re-examination, for the sole purpose of not allowing Cathy to have the last word. But he fails to dispel the aura her cross-examination has induced, of something not being quite right.